Chapter 310 Embryology, Anatomy, and Function of the Esophagus

Function

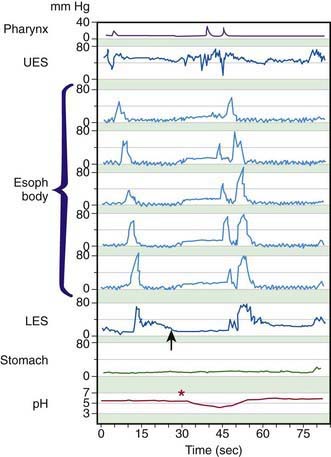

Swallowing is initiated by elevation of the tongue, propelling the bolus into the pharynx. The larynx elevates and moves anteriorly, pulling open the relaxing UES, while the opposed aryepiglottic folds close. The epiglottis drops back to cover the larynx and direct the bolus over the larynx and into the UES. The soft palate occludes the nasopharynx. The primary peristalsis thus initiated is a contraction originating in the oropharynx that clears the esophagus aborally (Fig. 310-1). The LES, tonically contracted as a barrier against gastroesophageal reflux (GER), relaxes as swallowing is initiated, at nearly the same time as the UES relaxation. The LES relaxation persists considerably longer, until the peristaltic wave traverses it and closes it. The normal esophageal peristaltic speed is ∼3 cm/sec; the wave takes ≥4 sec to traverse the 12 cm esophagus of a young infant and considerably longer in a larger child. Facial stimulation by a puff of air can induce swallowing and esophageal peristalsis in healthy young infants, a reflex termed the Santmyer swallow.

In addition to relaxing to move swallowed material past the GEJ into the stomach, the LES normally relaxes to vent swallowed air or to allow retrograde expulsion of material from the stomach. Perhaps as an extension of these functions, the normal LES also permits physiologic reflux episodes, brief events that occur approximately 5 times in the 1st postprandial hour, particularly in the awake state, but are otherwise uncommon. Transient LES relaxation, not associated with swallowing, is the major mechanism underlying pathologic reflux (see Fig. 310-1).

310.1 Common Clinical Manifestations and Diagnostic Aids

Kahrilas PJ, Sifrim D. High-resolution manometry and impedance-pH/manometry: valuable tools in clinical and investigational esophagology. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:756-769.

Ravi K, Francis DL. New technologies to evaluate esophageal function. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2007;4:829-837.

Van Wijk MP, Benninga MA, Omari TI. Role of the multichannel intraluminal impedance technique in infants and children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:2-12.

Willging JP, Thompson DM. Pediatric FEEST: fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing with sensory testing. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2005;7:240-243.