CHAPTER 24 Elimination Conditions

TOILET TRAINING AS A DEVELOPMENTAL MILESTONE

Toilet training, like every developmental milestone, is the compilation of numerous neurobiological processes affected by social opportunities, cultural expectations, and temperamental tendencies. Infants develop object permanence, the basis for the toddler’s fascination and fear of stool’s disappearance down the toilet. As toddlers pass through the sensorimotor phase, they busily explore the world, entering the bathroom to investigate. The child younger than 2 years may have phases of separation difficulties and is eager to mimic. This creates opportunities to watch parents use the bathroom and imitate them by sitting on the potty chair at the same time. As the child enters the preoperational stage, language develops rapidly. Now the child can indicate when diapers are wet or when he or she needs to defecate. In this egocentric phase, the child is highly focused on himself or herself. Along with “It’s mine” and “I do it,” the child might interrupt anything and everything when the urge to defecate or urinate comes.

TOILET TRAINING

Significance

TYPICAL AGE AT CONSOLIDATION AND TRENDS

Children in the United States typically become toilet trained between 2 and 3 years of age. At this stage, children are neurologically capable of sensing and containing stool and urine, and they have the language and motor skills to get to the toilet. Over the years, the completion of training has occurred at slightly older ages. Data from the late 1980s revealed that children completed toilet training at an average age of 24 to 27 months.1 In contrast, in the 1990s, U.S. girls were found to complete toilet training at an average age of 35 months and boys at 39 months.2

Several explanations regarding the phenomenon of later toilet training are proposed. With cheaper, more effective, and larger-sized diapers and training pants, older and larger children can easily use them. Cultural norms and parenting styles have also changed. Years ago, parents were given direct parenting advice, specific instructions about when to put the child to bed, how much to give at each feeding, and when and how to toilet train. Beginning with Dr. Spock in the 1940s, parents have been increasingly encouraged to trust their own instincts when parenting a child, rather than to follow the same uniform directions for every child.3 T. Berry Brazelton expanded this mindset specifically to toilet training.4 Endorsing a child-centered approach, Brazelton allowed children to take the lead in the training process. Rather than forcing the child to adhere to an imposed schedule of when to train, parents were encouraged to read a child’s signals that indicated readiness. When children express interest in toileting, have the developmental skills to accomplish the task, and have regularity in stooling and urinating, then parents step in to guide the process. Barton Schmitt later reincorporated specific parent responsibilities in the toilet training process, such as prompting practice runs, responding to successes, and responding to accidents.5

The parenting perspective may differ from one cultural group to another. For example, African American parents tend to start training their children at younger ages and are more likely than white parents to agree that it is important for a child to be trained before 24 months.2 Not surprisingly, nonwhite children are more likely to be trained earlier than their white peers.2

Blum and colleagues studied a large cohort of children to identify factors associated with later toilet training.6 More than 400 children, mostly Caucasian children at the top of the social strata, were monitored. The children who completed toilet training after age 3 years were compared with those who were trained before age 3. Later trainers started training later (at 22.3 vs. 20.6 months), were more likely to be constipated (41.7% vs. 13.2%), and exhibited more stool toileting refusal (56.7% vs. 17.9%) than peers who trained earlier. There were no differences between the two groups in parenting stress, birth order, or daycare participation.

TOILETING READINESS

Several developmental abilities are needed for a child to be toilet trained (Table 24-1). These are referred to as readiness skills. When parents ask when to train the child, it is helpful to provide a checklist of what the child needs to be able to do and an age range in which he or she is expected to do it.

| Readiness Skills | Age (Months) at Acquisition |

|---|---|

| Get to the toilet | 12-16 |

| Be aware of bladder/bowel sensation | 15-24 |

| Pull down pants and underpants | 18-24 |

| Sit on the toilet | 26-31 |

| Hold in urine/feces (dry for 2 hours) | 26-35 |

| Communicate the need to urinate/defecate | 26-34 |

| Use toilet without adaptive seat | 31-36 |

To train, a child should be dry for 2 hours at a time. This indicates regularity and bladder capacity that are adequate for using the toilet at reasonable intervals without interrupting daily activities. The child must communicate the need to go and his or her desire for access to the toilet. This can be accomplished with words, pointing, or signs. Families should be advised to pick toilet words that are socially acceptable and will be recognized in different settings, such as at school and at friends’ homes. To be independent in toileting, a child must have the motor skills to get to the toilet and must be secure enough to sit comfortably on the toilet or potty chair. Children with neurological deficits may need special apparatus so that they are stable on the toilet. The ability to pull down underpants and pants, including fasteners, is an additional requisite motor skill.

In many cultures, infants are “trained” to defecate and urinate over the toilet.7 This training is behavioral, accomplished by a parent very closely watching the child for signs of imminent voiding, such as a red face, a typical cry, or a typical posture. The parent removes diapers or underwear and holds the infant over a toilet. Infant training necessitates a great deal of consistency from parents and regularity in stooling and urinating patterns in infants. Interest in the US has resurged as “Elimination communication”, considered an extension of parent-child connections and a step toward toilet training. Studies of the benefits, side effects, and long-term outcomes of infant toilet training are not available.

Current Practices

RELEVANT RESEARCH

There is little research support for a single best, evidence-based method of toilet training a child.8 One review concluded that no randomized, controlled studies of preschoolers provide evidence for treating problems related to toilet training.9 The largest body of evidence stems from Azrin and Foxx, whose intensive approach breaks training into individual steps and is effective for both developmentally abnormal and typically developing children.10 Although Brazelton’s child-oriented approach is currently perhaps the most commonly used,11 no outcome data have been published since his original report.

Difficulty in Toilet Training

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THIS PROBLEM?

Increasing data are available regarding children who are not able to toilet train or have more trouble than expected. Based on his extensive experience, Schmitt suggested that the most common cause of delayed toilet training is refusal or resistance but also emphasized that these children are often enmeshed in a power struggle with their parents.12 Schonwald and associates furthered the understanding of difficulty in toilet training by demonstrating these children’s significant tendency to have difficult temperamental traits outside of their toileting difficulties.13 Children who were referred to a tertiary care center for failure to toilet train were less easygoing temperamentally and were more likely than easily trained children to have a negative attitude, be poorly adaptable, be less persistent, and be more hesitant in new situations. They were also substantially more constipated than were peers who trained easily. In comparisons of parents of such children with parents of typically trained children, no difference in parenting styles were found. Blum and colleagues confirmed that constipation in children with toilet training difficulty occurs before the toilet refusal14; theoretically, it hurts the child to stool, and so the temperamentally at-risk child then avoids stooling; this leads to more constipation and pain, and a vicious cycle ensues.

MANAGEMENT OF TOILET REFUSAL

Few interventions regarding late toilet training have been studied.15 Successes associated with such interventions have been minimal. Taubman and coworkers demonstrated that (1) discouraging negative terms for feces and (2) praising children who defecate into diapers before training began (using a child-oriented approach) did not decrease the incidence of stool toilet refusal but did shorten its duration.16

Late toilet training interventions must account for the child’s temperament, constipation status, and the parent-child dynamics that often develop around the toilet training power struggle. A group treatment approach has been one effective model that addresses these elements in a 6-week program.17

ENCOPRESIS

Significance

Encopresis is commonly defined as stool incontinence, typically of an involuntary nature as a result of overflow around constipated stool that dilates the distal rectum. The definition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, however, identifies encopresis only as repeated passage of stool into inappropriate places by a child who is both chronologically and developmentally older than 4 years.18 This definition can include both voluntary and involuntary situations but excludes those with stool incontinence resulting directly from physiological effects of a substance or caused by a general medical condition (except, of course, constipation). Because children typically are fully toilet trained by 3 years, those who are older than 4 years with stool that is evacuated anywhere other than into the toilet are considered abnormal. Their defecation must be considered medically and behaviorally; thus, those older than 4 years with ongoing symptoms are considered to have encopresis. In fact, most children with encopresis present before they are 7 years old.19

THE HIDDEN PROBLEM

Unlike more obvious developmental and behavioral issues, encopresis is not easily discussed among parents. In contrast to children with sleep problems and tantrums, families of children with encopresis have rarely heard of another child with the same problem. Typically, families approach encopresis as a behavior problem, attributing willfulness as the cause. They may associate encopresis with filth, embarrassment, and serious psychiatric pathology, with no understanding of its underlying cause. Although Internet access creates unprecedented opportunities for research about medical conditions in the privacy of a parent’s own home, few parents would know to search “encopresis.”

INCIDENCE HARD TO CONFIRM

It is difficult to determine the true prevalence of encopresis because of its private nature and families’ and children’s reluctance to discuss it. Some authors report that 1% to 3% of children between ages 4 and 11 years suffer from encopresis20 (Table 24-2); similarly, the prevalence of encopresis was 4.1% among 5- to 6-year-olds and 1.6% among 11- to 12-year-olds in a large, population-based study in The Netherlands, with an increased incidence among those with psychosocial problems.21

| Age (Years) | Incidence |

|---|---|

| 4 | 2.8% |

| 5-6 | 4.1% |

| 6 | 1.9% |

| 10-11 | 1.6% |

| 11-12 | 1.6% |

EMOTIONAL EFFECT RATHER THAN CAUSE

Traditionally, the perceived association between encopresis and serious emotional problems triggered mental health referrals for children presenting with stool leakage or larger accidents.22 Children with stool accidents are at risk for physical and sexual abuse, perhaps because their accidents trigger anger in uninformed caregivers, although encopresis may also be a physical response to anal trauma.23 Children who are traumatized can lose continence as a sign of regression, like all other fragile developmental skills that deteriorate in times of stress. Stool incontinence can also be a protection against abuse; a child may discover that stool in the underwear will keep an abuser away. In all cases of children presenting with encopresis, possible abuse must be explored, although it is rarely found.

Children with encopresis can develop emotional problems, which may be a consequence of being teased and embarrassed, leading to poor self-esteem, anxiety, reduced school performance, and impaired social success.24 They may suffer when uneducated families exacerbate their sense of failure, expecting the child to stop the accidents despite his or her inability to control them. However, in most cases, encopresis is not symptomatic of a larger psychiatric problem.25

Cause

More than 90% of cases of encopresis result from constipation.24 Anything that causes constipation can therefore cause encopresis. In rare cases, the cause is a neurological disorder, such as a tethered spinal cord. Children with tethered cords may have been continent and then regressed; as the child grows, the spinal cord stretches as a result of the abnormal tethering, causing neurological impairment. In addition to deterioration of continence, these children also may have gait changes, lower back pain, abnormal lower extremity reflexes, or lower back skin manifestations including lumbosacral dimples or hair tufts.

CONSTIPATION OF VARYING DEGREES

Most children with encopresis are constipated.26 However, mild constipation can lead to overflow incontinence, whereas some severely constipated children have no encopresis. The critical variable seems to be the amount of rectal dilatation, not the absolute amount of stool in the bowel. Historical details elucidate the degree of impaction and dictate the intensity of intervention.

CAUSES OF CONSTIPATION

Constipation is common in U.S. children, affecting 5% of children aged 4 to 11 years.27 In most children, there is no specific abnormality or disease that necessitates treatment. Again, history and physical examination identifies children in need of investigation for a pathological cause of constipation. The symptoms of slow growth, depression, and weight gain and a positive family history are indications for thyroid function testing to assess for hypothyroidism. A thorough physical examination should include an assessment for any signs of neuropathy or myopathy, which could manifest in the gastrointestinal tract with constipation. Conditions such as cerebral palsy or myelomeningocele are frequently associated with chronic constipation. It is also possible on physical examination to detect anatomical abnormalities, such as a very anterior ectopic anus or anal ring stenosis. Although inflammatory bowel disease more commonly manifests with loose stools, constipation is possible, and systemic symptoms, anal tags, weight loss, and a family history of autoimmune disorders may indicate the need for a workup for these conditions. Severe constipation is also possible in celiac disease.

Diagnosis

HISTORY AND EXAMINATION REGARDING CONSTIPATION AND NEUROLOGICAL PATHOLOGY

As part of the developmental history, details of toilet training, when and which methods were used, and successes or failures can be helpful. Some children with stool accidents have never actually been toilet trained. They have never developed the skill to sense impending defecation, hold it in, and then evacuate on the toilet. These children require directed behavioral programming that focuses on identifying the body signal of a distended rectum, maintaining control over the body by contracting the external sphincter, and cooperating with using the toilet. Toilet refusal often leads to constipation as well, and thus treatment to improve bowel regularity and consistency is often needed.

RADIOLOGICAL EXAMINATIONS

For most children with encopresis, assessment can be limited to the history and physical examination alone. An abdominal radiograph is a useful adjunct when the history is vague, when the child is uncooperative with examination, or when the family and child would benefit from concrete evidence of constipation. The North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition recommends an abdominal film when the child’s constipation history is in doubt, if the child or parent refuses a digital examination, or if the digital examination is to be avoided because of a history of trauma.28 However, a review of 392 studies of the evaluation of children with constipation and encopresis revealed that the evidence of an association between the clinical symptoms of constipation and fecal load on radiographs was in-conclusive.29 Lumbosacral spine films or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is indicated when lower extremity neurological examination findings are abnormal or lumbosacral abnormalities are visualized. Children treated for encopresis for prolonged periods without expected improvement may also be considered for lumbosacral MRI in search of tethered cord with unusually silent neurological examination findings.

Treatment

BEHAVIORAL STRATEGIES

From the start of treatment, patients and their families should learn that combined medication and behavioral interventions are vital for successful outcomes.30 Because the bowel wall is stretched and cannot send the brain signals for defecation, a schedule for evacuation is necessary until normal feedback systems are restored. Even if the child does not feel the need to defecate, he or she should sit on the toilet and try to evacuate the bowel regularly. Sit-down times can take place 30 minutes after each meal, lasting for 10 minutes each. Most children do not want to sit during school, so the midday sit-down can take place on weekends only. Younger children may benefit from small rewards or treats for cooperating with the sit-down time and trying to defecate. Treats should be small and inexpensive, such as stickers, an extra story at bedtime, or use of a favorite toy. They also may find it helpful to blow up a balloon or place their hand on their lower abdomen and feel their abdomen push outward when bearing down.

MEDICATION FOR CONSTIPATION

In addition to the initial education and demystification, encopresis treatment starts with a bowel cleanout. More aggressive regimens tend to be associated with better results. Children aged 7 years and older usually can be treated with enemas. One effective treatment plan repeats a 3-day cycle consisting of an enema on day 1, a bisacodyl tablet on day 2, and a bisacodyl suppository on day 3; then the cycle is repeated three times, thereby running 12 to 15 days. Several cleanout schedules can be used regularly, including molasses enemas, polyethylene glycol with electrolyte cleanouts, and high doses of polyethylene glycol without electrolytes. No single cleanout method has been demonstrated to be most effective, but a major objective should be to avoid increasing the child’s accident frequency during school hours.

RELEVANT RESEARCH OF EFFICACY

One review of 16 randomized or quasi-randomized trials of more than 800 children with encopresis revealed that behavioral intervention plus laxative therapy, rather than either alone, improved fecal continence in children with encopresis.30 Most children treated for encopresis have meaningful improvement, although there are few data to guide prediction. Recovery rates have been reported as 30% to 50% after 1 year and 48% to 75% after 5 years.

ENURESIS

Primary Monosymptomatic Nocturnal Enuresis

Enuresis is defined as repeated voiding of urine into clothes during the day or into the bed during the night in a child who is chronologically and developmentally older than 5 years.18 The accidents must occur at least twice per week for 3 months or cause significant distress or impairment. This broad category is divided into primary uncomplicated (monosymptomatic) nocturnal enuresis (no period longer than 6 months of being dry at night, no daytime symptoms), secondary or complicated nocturnal enuresis (nighttime wetness after a period of 6 months of being dry and/or the presence of daytime symptoms), and daytime incontinence. Monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis rarely signifies an underlying organic abnormality, whereas presence of daytime symptoms is more likely to signify a disorder. Regardless of the type of enuresis, the workup and treatment needs to take into account both medical and psychological implications common to children with urine accidents.

SIGNIFICANCE

The achievement of nighttime continence results from a maturing of the urological and neurological systems. Sympathetic stimulation from nerves T11 to L2 induces detrusor muscle relaxation so the bladder can fill, while the internal sphincter muscle (bladder neck) contracts to contain the urine.31 Infants have a small bladder that reflexively empties without voluntary control. To empty, parasympathetic fibers from nerves S2 to S4 activate the detrusor muscle to contract, increasing the intravesicular pressure and relaxing the bladder neck. Voluntary control comes from communication between the pontine micturition center and the sacral nerves, allowing voiding to be inhibited. Over the first 2 years of life, bladder capacity increases, along with central nervous system maturity, and thus the child develops greater awareness of bladder filling. Bladder capacity further increases between 2 and 4 years of age, when voluntary control during the day develops.

INCIDENCE AND RESOLUTION RATE

Most children are continent at night within 2 years of completing daytime toilet training. However, by 7.5 years, 15.5% of children remain wet at night, although only 2.5% wet often enough to meet criteria for enuresis.32 Each year, bedwetting self-resolves in 15% of children,33 so that 1% to 2% of 15-year-olds remain wet at night.34 For unclear reasons, boys are twice as likely to suffer from this problem.19 Bedwetting seems to occur with similar prevalence across cultures, ethnicities, and socioeconomic classes.

EFFECT ON CHILDREN AND FAMILIES

Nocturnal enuresis is rarely associated with serious psychiatric disorders.35 However, experiencing the frustration of persistent bedwetting can affect the emotional well-being of affected children. At a minimum, affected children face barriers to activities involving an overnight stay, such as camp, sleepovers, and vacations. Furthermore, affected children have less competence socially, lower school success rates, and higher than expected levels of behavioral problems.36 For example, 50 children with enuresis were compared with children suffering from asthma and heart problems with regard to their attitudes toward their conditions.37 Children with bedwetting had more negative feelings about their condition, more maladaptive coping strategies, and more negative adjustment to the stress bedwetting causes, regardless of the frequency of nighttime accidents and history of treatment failures. Of importance is that positive attitude was correlated with improved response to treatment.

Nighttime bedwetting typically is stressful to families of affected children, particularly when parents are uninformed about the accidental nature of the disorder. Parents of children who wet the bed report significant levels of withdrawn, anxious, and depressed symptoms in their children, which indicates the negative parental perception of these children.35 Traditionally, children with enuresis have been considered at increased risk for child abuse; according to a study of 889 mothers in Turkey, child abuse was reported in 86% of children with enuresis.38

Other studies indicate that children with bedwetting may have a higher incidence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), a finding that matches common clinical experience. In one study of 120 children aged 6 to 12 years who were referred to an incontinence program, 37.5% met criteria for ADHD39; this percentage was far greater than the expected rate of 7.5%.40 Similarly, children with ADHD seem to have more voiding dysfunction than do those without ADHD.41 Furthermore, studies show significantly lower success rates of bedwetting treatment by alarm or medication in children with ADHD than in those without ADHD, perhaps because of the greater difficulty with compliance by children with ADHD.42

CAUSES

Genetics

It is unknown to most affected patients that nocturnal enuresis frequently runs in families. However, parents rarely reveal their own history of bedwetting to a spouse or child, until specifically probed about the topic. In fact, most children with bedwetting have an extended family history of the condition.43 The child of one parent with a history of bedwetting has a 44% risk of the same condition; if both parents wet their beds as children, their offspring have a 77% chance of also being affected.44 Several studies have shown a strong genetic linkage on chromosomes 13q, 12q, 22q, and 8q, although heterogeneity exists.45 Genetic testing is currently not useful in the diagnosis or treatment of enuresis.

Sleep

Some children with enuresis do not wake in response to the sensation of a full bladder. Parents have long claimed that their children with bedwetting were heavy sleepers, a finding often attributed to a selection bias because their child with enuresis is the only child they awaken to urinate. However, studies have shown that children with bedwetting have a higher threshold for arousal: for example, a stimulus that awakened 40% of controls awakened only 9% of enuretic patients in one sample of 33 boys.46 Sleep studies of children with bedwetting are not uniformly distinct from those of controls, and there is no specific time of the night or stage of sleep when enuresis is more likely to occur.47

Decreased Bladder Capacity

A mismatch between urine production and the amount of urine contained in the bladder at night seems to cause bedwetting as well. In the normal circadian rhythm, the body produces less urine per hour at night than during the day; in some children nocturnal urine output may fail to decrease and therefore overwhelms the bladder’s ability to prevent outflow. Other children may secrete insufficient amounts of antidiuretic hormone at night or may have resistance to antidiuretic hormone produced. This population may be helped by desmopressin (DDAVP), which decreases urine production and is further described in the section on medications. A final explanation for mismatch is decreased functional bladder capacity, which means the bladder empties before it is filled, although study findings are mixed.48

DIAGNOSIS

History

Obtaining a thorough history is vital in the diagnostic and therapeutic process for children with bedwetting. The full medical and developmental histories may link bedwetting to a systemic disorder or to global developmental problems. Details about urination and defecation clarify whether enuresis is primary or secondary and whether constipation is causal or comorbid. Constipation is a common cause of enuresis; a full bowel can interfere with bladder sensation, impede bladder emptying, and reduce bladder capacity. Information from the family history of nocturnal enuresis can help diagnostically, in view of the child’s increased risk, and can relieve some of the child’s isolation and shame instantly. Information from the social history should specifically include possible trauma, abuse, recent stressors, and emotional consequences of bedwetting. The child and family should be asked how the bedwetting has interfered with social opportunities and family function. Methods implemented to address the problem, such as alarms, incentives, punishments, and medications, must be reviewed in detail. Often, the parent may have used incentives without necessary strategies to address the cause of wetting (i.e., treat constipation), or they used alarms when the child was too young or they used them inappropriately.

TREATMENT

Alarms

Bedwetting alarms, first described before 1900, are the mainstay of nocturnal enuresis treatment.49 The alarm, which may sound or vibrate, is connected to the child’s underwear and goes off when moisture is detected. The child must rouse or be aroused by parents, must urinate, must change his or her underwear and bed sheet, and re-place the alarm. Visualization should be practiced before going to sleep; the child imagines waking to the alarm, going to the bathroom, urinating, changing, fixing the bed and re-placing the alarm, and returning to sleep.50 In addition, before bed, the child should complete a practice run, pretending to finish each of these steps. It is helpful to recommend that parents reward their child in the morning; for the first week, children should receive a treat for waking with the help of a parent; for the second week, for waking independently; and after that, for waking up dry in the morning. Over the weeks, the urine mark will probably shrink in size, as the child wakes earlier in the void. For maximum success, after the child has been dry for 1 month, “over-treating” by having the child drink a glass of water before bed is effective.51 Three to 4 months of alarm use is often required, and considerable motivation is necessary for both the child and parents. Alarms cost from $40 to $100 dollars and may or may not be covered by medical insurance. After use of the alarm, some children learn to wake to urinate, but most sleep through the night and remain dry. Alarms have been found to cure at least two thirds of affected children, with a low relapse rate.52

Medications

Medications also can be a useful component in enuresis treatment. DDAVP, an antidiuretic hormone analogue, is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for nocturnal enuresis. Given as a tablet or intranasal spray before bedtime, DDAVP decreases urine production for up to 7 hours.53 On the basis of this mechanism of action, it seems that children with nocturnal polyuria are most likely to be responsive. DDAVP can be used on an as-needed basis, a method often preferred by families because of its high cost. DDAVP has few side effects, but drinking after taking DDAVP at night should be avoided in order to prevent water intoxication, which can rarely result in hyponatremic seizures. Imipramine, a tricyclic antidepressant, is also approved for bedwetting, but its risk for cardiotoxicity and its narrow margin of safety limits its utility. The mechanism of imipramine is unknown, but it has an efficacy rate of 30% to 50%. When DDAVP or imipramine is discontinued, the relapse rate for both is 60%. Large meta-analyses confirm the greater success rates of alarms over these medications; a lower relapse rate and less toxicity are associated with alarm use.54 Alternatively, DDAVP or imipramine can be used along with the alarm, in some cases leading to improved outcomes.55

Alternative treatments for nocturnal enuresis, although popular, currently lack conventional evidence to support their widespread use. Limited evidence-based data support the use of hypnosis, psychotherapy, and chiropractics in bedwetting treatment56; however, a growing body of literature substantiates the role of acupuncture, long practiced in Chinese medicine and studied internationally in such countries as the United States, Italy, Japan, Korea, and Romania.57

Daytime Incontinence

SIGNIFICANCE

Incidence

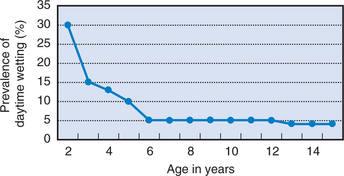

Daytime continence is achieved in 70% of children by age 3 years and in 90% by age 6 years (Fig. 24-1).58 The exceptions raise suspicion for organic pathology, as do cases in which children were previously dry during the day and later suffer from accidents. Daytime incontinence is most commonly caused by treatable or benign conditions, but the rare and potentially serious origins must be investigated. Fortunately, a thorough history, physical examination, and urinalysis are generally adequate diagnostically to identify these conditions.

Causes

BLADDER INSTABILITY

Bladder instability is the most common cause for daytime accidents. The differential diagnosis should include, foremost, constipation, which should be considered as a trigger for bladder spasm. Constipation and encopresis occurred in 35% of children with daytime incontinence in one study of almost 1500 Swedish elementary school students59; this finding confirmed the clinical experience of this common copresentation. Dysuria also frequently signifies a urinary tract infection, diagnosed with a urine culture. In teenage girls, pregnancy must also be considered.

ABNORMAL SPHINCTER CONTROL

Spinal cord abnormalities rarely cause daytime incontinence, but because of their serious morbidity, they must be carefully considered in every patient with symptoms. Bladder function can be affected by a lesion at any level of the spine. A tethered cord manifests as a child grows. In contrast to the normally free-floating spinal cord within the canal, the tethered cord is abnormally attached to a local structure; with growth and movement, the cord and its blood supply stretch and are damaged. In addition to a change in bladder or bowel function, children with a tethered cord may have back pain, gait changes, scoliosis, and abnormal reflexes. External features include a sacral tuft or pit. Obtaining a sacral MRI is indicated, followed by a referral to a neurosurgeon if an abnormality is noted.

1 Seim HC. Toilet training in first children. J Fam Pract. 1989;29:633-636.

2 Schum TR, McAuliffe TL, Simms MD, et al. Factors associated with toilet training in the 1990s. Ambul Pediatr. 2001;1:79-86.

3 Spock B. The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care. New York: Duell, Sloan & Pearce, 1946.

4 Brazelton TB. A child-oriented approach to toilet training. Pediatrics. 1962;29:121-128.

5 Schmitt BD. Toilet training: Getting it right the first time. Contemp Pediatr. 2004;21:105-122.

6 Blum NJ, Taubman B, Nemeth N. Why is toilet training occurring at older ages? A study of factors associated with later training. J Pediatr. 2004;145:107-112.

7 Sun M, Rugolotto S. Assisted infant toilet training in a Western family setting. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2004;25:99-101.

8 Christophersen ER. The case for evidence-based toilet training. Arch Dis Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:1153-1154.

9 Brooks RC, Copen RM, Cox DJ, et al: Review of the treatment literature for encopresis, functional constipation, and stool-toileting refusal. Ann Behav Med, 22: 260-267.

10 Azrin NH, Foxx RM. Toilet Training in Less than a Day. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1974.

11 Brazelton TB, Sparrow JD. Toilet Training, The Brazelton Way. Cambridge, MA: De Capo Press, 2004.

12 Schmitt BD. Toilet training problems: Underachievers, refusers, and stool holders. Contemp Pediatr. 2004;21:71-82.

13 Schonwald A, Sherritt L, Stadtler A, et al. Factors associated with difficult toilet training. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1753-1757.

14 Blum NJ, Taubman B, Nemeth N. During toilet training, constipation occurs before stool toileting refusal. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e520-e522.

15 Shaikh N. Time to get on the potty: Are constipation and stool toileting refusal causing delayed toilet training? J Pediatr. 2004;145:12-13.

16 Taubman B, Blum NJ, Nemeth N. Stool toileting refusal: A prospective intervention targeting parental behavior. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:1193-1196.

17 Schonwald A, Huntington N, Lesser T, et al: Toilet School: A Promising Intervention for Difficult and Late Toilet Training. Poster presented at the Annual Meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies, Washington, DC, May 2005.

18 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 2000.

19 Schonwald A, Rappaport L. Consultation with the specialist: Encopresis: Assessment and management. Pediatr Rev. 2004;25:278-283.

20 Loening-Baucke V. Encopresis. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2002;14:570-575.

21 van der Wal MF, Benninga MA, Hirasing RA. The prevalence of encopresis in a multicultural population. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;40:345-348.

22 Foreman DM, Thambirajah M. Encopresis was associated with child sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 1998;22:337.

23 Morrow J, Yeager CA, Lewis DO. Encopresis and sexual abuse in a sample of boys in residential treatment. Child Abuse Negl. 1997;21:11-18.

24 Benninga MA, Buller HA, Heymans HS, et al. Is encopresis always the result of constipation? Arch Dis Child. 1994;71:186-193.

25 Loening-Baucke V. Encopresis and soiling. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1996;43:279-298.

26 Voskuijl WP, Heijmans J, Heijmans HS, et al. Use of Rome II criteria in childhood defecation disorders: Applicability in clinical and research practice. J Pediatr. 2004;145:213-217.

27 Borowitz SM, Cox DJ, Tam A, et al. Precipitants of constipation during early childhood. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16:213-218.

28 Baker SS, Liptak GS, Colletti RB, et al. Constipation in infants and children: Evaluation and treatment. A medical position statement of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;29:612-626.

29 Reuchlin-Vroklage LM, Bierma-Zeinstra S, Benninga MA, et al. Diagnostic value of abdominal radiography in constipated children: A systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:671-678.

30 Brazzelli M, Griffiths P. Behavioural and cognitive interventions with or without other treatments for defaecation disorders in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD002240, 2005 [update. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2). 2006. CD002240]

31 Silverstein DM. Enuresis in children: Diagnosis and management. Clin Pediatr. 2004;43:217-221.

32 Butler RJ, Golding J, Northstone K, et al. Nocturnal enuresis at 7.5 years old: Prevalence and analysis of clinical signs. BJU Int. 2005;96:404.

33 Forsythe WI, Redmond A. Enuresis and spontaneous cure rate. Study of 1129 enuretics. Arch Dis Child. 1974;49:259-263.

34 Byrd RS, Weitzman M, Lanphear NE, et al. Bedwetting in US children: Epidemiology and related behavior problems. Pediatrics. 1996;98:414-419.

35 Van Hoecke E, Hoebeke P, Braet C, et al. An assessment of internalizing problems in children with enuresis. J Urol. 2004;171:2580-2583.

36 Landgraf JM, Abidari J, Cilento BGJr, et al. Coping, commitment, and attitude: Quantifying the everyday burden of enuresis on children and their families. Pediatrics. 2004;113:334-344.

37 Wolanczyk T, Banasikowska I, Zlotkowski P, et al. Attitudes of enuretic children towards their illness. Acta Paediatr. 2002;91:844-848.

38 Can G, Topbas M, Okten A. Child abuse as a result of enuresis. Pediatr Int. 2004;46:64-66.

39 Baeyens D, Roeyers H, Hoebeke P, et al. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children with nocturnal enuresis. J Urol. 2004;171:2576-2579.

40 Barbaresi W, Katusic S, Colligan R, et al. How common is attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? Towards resolution of the controversy: Results from a population-based study. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2004;93:55-59.

41 Duel BP, Steinberg-Epstein R, Hill M, et al. A survey of voiding dysfunction in children with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. J Urol. 2003;170:1521-1523.

42 Crimmins CR, Rathbun SR, Husmann DA. Management of urinary incontinence and nocturnal enuresis in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Urol. 2003;170:1347-1350.

43 Elian M, Elian E, Kaushansky A. Nocturnal enuresis: A familial condition. J R Soc Med. 1984;77:529-530.

44 Bakwin H. The genetics of enuresis. In: Kolvin I, MacK-eith RC, Meadow SR, editors. Bladder Control and Enuresis. London: William Heinemann; 1973:73.

45 von Gontard A, Schaumburg H, Hollmann E, et al. The genetics of enuresis: A review. J Urol. 2001;166:2438-2443.

46 Wolfish NM, Pivik RT, Busby KA. Elevated sleep arousal thresholds in enuretic boys: Clinical implications. Acta Paediatr. 1997;86:381-384.

47 Neveus T. The role of sleep and arousal in nocturnal enuresis. Acta Paediatr. 2003;92:1118-1123.

48 Korzeniecka-Kozerska A, Zoch-Zwierz W, Wasilewska A. Functional bladder capacity and urine osmolality in children with primary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2005;39:56-61.

49 Kristensen G, Jensen IN. Meta-analyses of results of alarm treatment for nocturnal enuresis-Reporting practice, criteria and frequency of bedwetting. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2003;37:232-238.

50 Mellon MW, McGrath ML. Empirically supported treatments in pediatric psychology: Nocturnal enuresis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2000;25:193-214.

51 Wagner W, Johnson SB, Walker D, et al. A controlled comparison of two treatments for nocturnal enuresis. J Pediatr. 1982;101:302-307.

52 Fritz G, Rockney R, Bernet W, et al. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with enuresis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:1540-1550.

53 Glazener CMA, Evans JHC. Desmopressin for nocturnal enuresis in children. Cochrane. Database Syst Rev (3). 2002. CD002112

54 Glazener CM, Evans JH, Peto RE. Alarm interventions for nocturnal enuresis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2). 2003. CD002911

55 Hjalmas K, Arnold T, Bower W, et al. Nocturnal enuresis: An international evidence based management strategy. J Urol. 2004;171:2545-2561.

56 Glazener CM, Evans JH, Cheuk DK. Complementary and miscellaneous interventions for nocturnal enuresis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2). 2005. CD005230

57 Bower WF, Diao M, Tang JL, et al. Acupuncture for nocturnal enuresis in children: A systematic review and exploration of rationale. Neurourol Urodyn. 2005;24:267-272.

58 Robson WL. Diurnal enuresis. Pediatr Rev. 1997;18:407-412.

59 Soderstrom U, Hoelcke M, Alenius L, et al. Urinary and faecal incontinence: A population-based study. Acta Paediatr. 2004;93:386-389.

60 Casale AJ. Getting to the bottom of the issue. Contemp Pediatr. 2000;2:107-116.