14 Electrosurgery

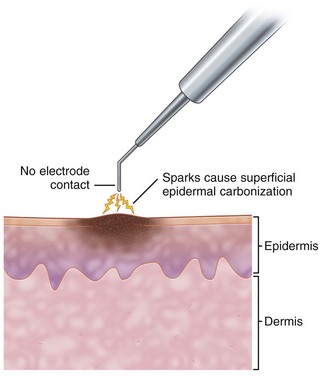

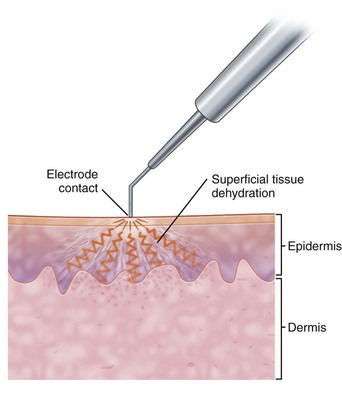

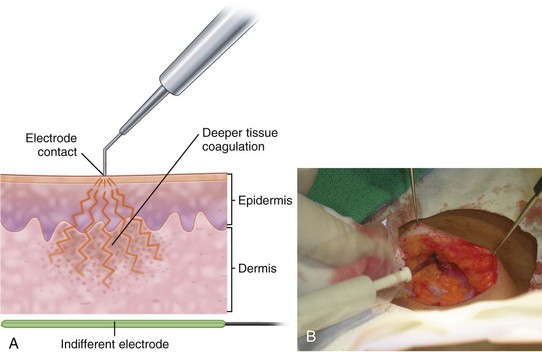

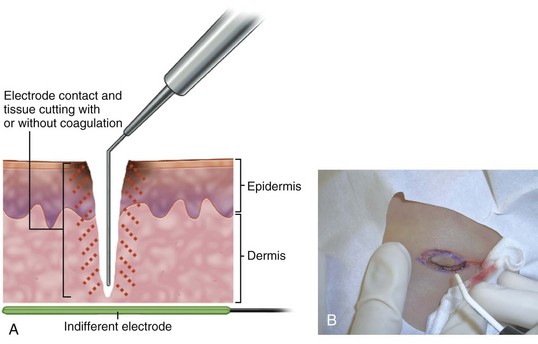

The major electrosurgical functions include fulguration, electrodesiccation, electrocoagulation, and electrosection (cutting). In fulguration, the electrode is held away from the skin so that there is a sparking to the surface (such as happens with lightning). In fact, the term fulguration comes from the Latin term fulgur, which means “lightning.” Fulguration produces a high-intensity but more shallow level of tissue destruction (Figure 14-1). With electrodesiccation, the active electrode touches or is inserted into skin to produce deeper tissue destruction (Figure 14-2). Epilation is a type of desiccation in which a fine-wire electrode is inserted into a hair follicle to literally “cook it.” Electrocoagulation is used to stop bleeding in deep and superficial surgery (Figure 14-3). In electrosection, the unit is set so the electrode cuts tissue (Figure 14-4). The higher the unit’s operating electrical frequency (not to be confused with power), the less tissue damage is left behind when using the cutting function.

Current can be applied either in a unipolar or bipolar fashion. The majority of electrosurgical units (ESUs) are unipolar. Unipolar refers to the fact that the current enters a site at the point of the electrode and passes through the body to a grounding plate to complete the circuit. With bipolar applications, the current travels from one point of the electrode, through the tissue, to another point of the electrode (e.g., with fine forceps, from point to point). No grounding plate is needed for this type of use. This reduces possible complications from burns at unwanted sites where the current can exit. It also reduces complications with pacemakers. The bipolar units are ideal to control bleeding since forceps can pinpoint and grasp a bleeder. When the current is applied, only the tissue between the tips of the forceps is affected (Figure 14-5).

Disadvantages of Electrosurgery

Electrosurgery Versus Cryosurgery

There may be a risk of developing human papilloma virus (HPV) in the respiratory tract from inhaling the plume (smoke) from an HPV lesion as it is being treated.1–3 Intact HPV DNA has been isolated from the plume of verrucae that were treated with electrosurgery and lasers. Therefore, it is prudent for all physicians to use a smoke evacuator while performing laser and electrosurgical treatment of verrucae and other viral lesions. (See Safety Measures with Electrosurgery, p. 167.) Unfortunately, evidence is insufficient to measure the magnitude of these risks. These personal risks, however, may be one factor used to determine the physician’s choice of therapy for viral lesions.

One disadvantage of cryotherapy over electrosurgery is that with cryosurgery the final result cannot be seen immediately, and there is more subjective judgment involved in performing the treatment. However, the degree of damage can be estimated accurately with more experience and by following certain guidelines (see Chapter 15). Cryosurgery also causes more postoperative swelling, which may be uncomfortable for the patient but is only a transient phenomenon.

Electrosurgery Versus Laser

Laser is an acronym for light amplified by stimulated emission of radiation. Laser technology uses focused light energy to affect cells. Many types of lasers are available to perform different functions (see Chapters 26 through 30). Electrosurgery is less expensive than laser surgery but is more limited in utility. The standard electrosurgical units are a fraction of the cost of a laser (as low as $1000 to 4000 compared to laser units costing $30,000 to $200,000). Most physicians face the choice of referring a patient for laser surgery versus doing electrosurgery in their own office. As with electrosurgery, the CO2 laser may be used to cut, coagulate, and ablate (destroy) tissue. It is most often used in the office for resurfacing procedures, such as in the treatment of rhytids (wrinkles) and skin surface irregularities; pigmentation; and small vessels. The pulsed dye laser or a similar yellow-light laser is unequivocally better than electrosurgery for treating large hemangiomas and maximizing the cosmetic result. These lasers are used very effectively to treat port-wine hemangiomas. Visible-light lasers obtain better cosmetic results when treating most other vascular lesions, such as angiomas and telangiectasias. They offer much less chance of scarring.

Equipment

Thermal Pencil/Battery Cautery

An inexpensive thermal “pencil” cautery (Figure 14-6) is a useful device to have for small skin lesions. They are also used to occlude the cut ends of the vasa when doing a vasectomy. This disposable device consists of two penlight batteries in a housing connected to a wire filament that heats up when activated. Reusable models are also available with disposable tips. These battery cautery units can be a useful tool for treatment around the eyes and on patients with pacemakers. The devices come in high- and low-temperature varieties; low-temperature devices are preferred in skin surgery.

Electrosurgical Units

Basic Electrosurgical Units (Noncutting, Lower Frequency)

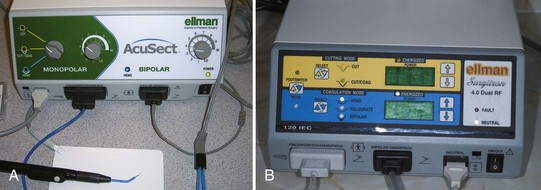

High-Frequency Units (up to 4 MHz)

Dual-Frequency Units (Unipolar 4 MHz and Bipolar 1.7 MHz)

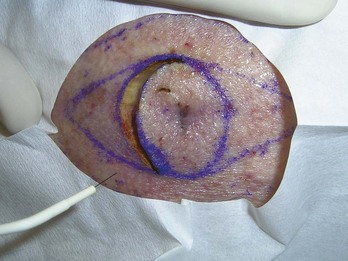

FIGURE 14-7 The Hyfrecator 2000 from the ConMed Corporation is a commonly used electrosurgical unit in the office.

Accessories

Hyfrecator

Ellman Surgitron Units

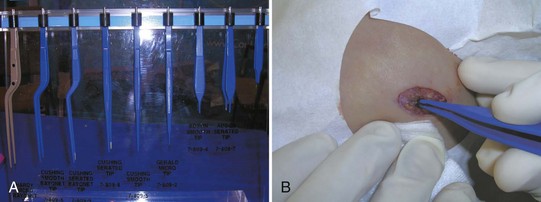

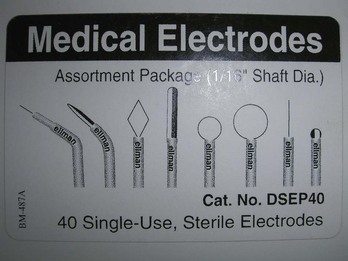

FIGURE 14-12 An assortment of medical electrodes for single use may be purchased from Ellman for use with the Surgitron.

Contraindications

Electrosurgical Techniques: General Principles

Power Setting

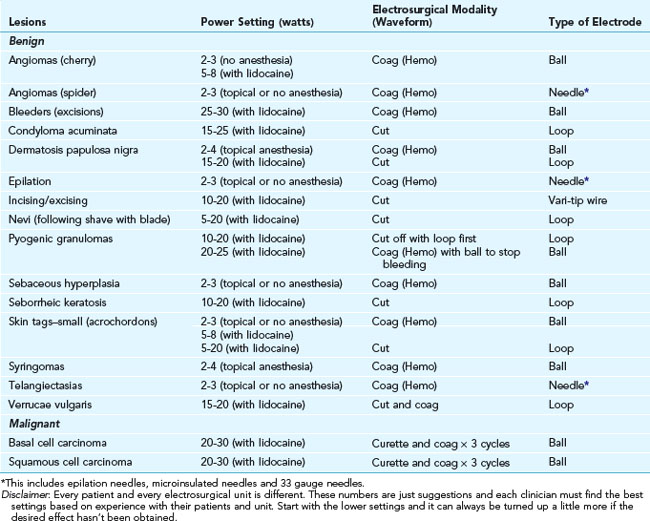

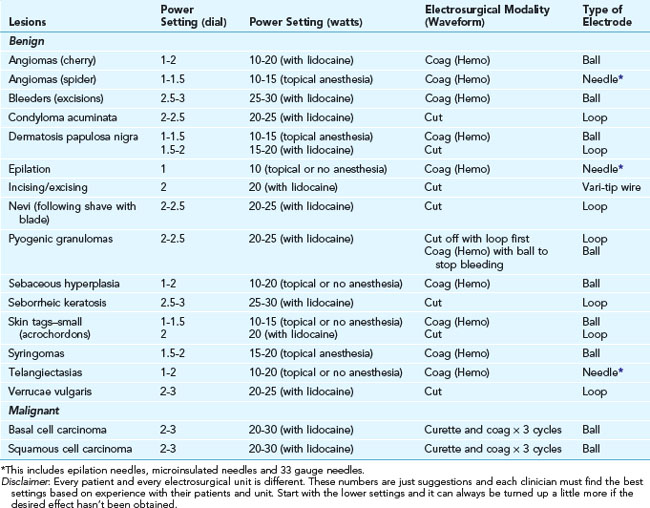

Every electrosurgical unit is different, and the desired setting will vary for each model, procedure, lesion, or patient. Even two supposedly identical electrosurgical models may require different settings. Therefore, the setting levels provided are only starting points (Tables 14-1 to 14-3 and Box 14-1). The basic principle for setting the correct power output is to start low and increase the power until the desired outcome (destruction, coagulation, or cutting) is achieved. For ablation/destruction, the tissue should bubble or turn gray. Keep in mind that destruction of tissue below the visible area of treatment can occur. The power setting for coagulation is generally higher than the setting needed for tissue destruction. A rule of thumb is to use the lowest power setting that accomplishes a given result so as to achieve cosmetically acceptable outcomes. It helps to moisten the tissue to provide better contact and allow a lower power setting.

|

Lesions |

Power Setting (watts on low) |

Type of Electrode |

|---|---|---|

| Benign | ||

| Angiomas (cherry) | 2–2.5 | Sharp or dull |

| Angiomas (spider) | 2–2.5 | Sharp or needle |

| Condyloma acuminata | 12–18 | Dull |

| Dermatosis papulosa nigra | 2–2.5 | Dull or sharp |

| Pyogenic granulomas | 16–20 or switch to high | Dull |

| Sebaceous hyperplasia | 2–2.5 | Dull |

| Seborrheic keratosis | 10–14 | Dull |

| Skin tags (acrochordons) | 2–2.5 | Sharp |

| Syringomas | 2–2.5 | Sharp |

| Telangiectasias | 2–2.5 | Sharp or needle |

| Verrucae vulgaris | 12–18 | Dull |

| Verrucae plana | 12–18 | Sharp or dull |

| Malignant | ||

| Basal cell carcinoma | 16–20 | Dull |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 16–20 | Dull |

Disclaimer: Every patient and every electrosurgical unit is different. These numbers are just suggestions and each clinician must find the best settings based on experience with their patients and unit.

TABLE 14-2 Approximate Range of Power settings with Radio-Frequency Surgery (Using Dual-Frequency Ellman Surgitron)

TABLE 14-3 Approximate Range of Power Settings with Radio-Frequency Surgery (Using Ellman Surgitron FFPF EMC)

Box 14-1 Electrosurgical Settings

Suggested Settings for Hyfrecator 2000 or Bovie 900

Anesthesia

Local anesthesia will be needed for virtually all electrosurgery with the exception of the treatment for telangiectasias, small skin tags, and fine angiomas where either no or topical anesthesia is adequate. Injecting 1% to 2% lidocaine with epinephrine before the procedure will provide painless electrosurgery. However, short bursts of low current can be less uncomfortable than needle anesthesia in some individuals. Topical anesthesia with ethyl chloride is contraindicated because ethyl chloride is flammable. Anesthetic creams (see Chapter 3, Anesthesia) can be used for anesthesia before treatment of facial telangiectasias and eliminates the effects of distortion from injectable anesthesia.

Practical Pearls Specific to Radiosurgery

Safety Measures with Electrosurgery

Safety Precautions to Avoid Potential Hazards

Transmission of Infection through Electrode

During sterile procedures options include the following:

Transmission of Infection through Smoke Plume or Spattering Blood

Transmission of infection through a smoke plume or spattering blood is a potential risk when treating lesions of viral origin. This is especially true when treating HPV infection in all types of warts. Intact HPV DNA has been recovered in the smoke plume of verrucae treated with electrosurgery and the carbon dioxide laser.1–3 One case report suggests that a physician acquired an HPV infection of the larynx (laryngeal papillomatosis) while performing laser therapy on HPV-infected lesions.1

A publication of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) states that research studies have confirmed that smoke plume can contain toxic gases and vapors such as benzene, hydrogen cyanide, and formaldehyde, bioaerosols, dead and live cellular material (including blood fragments), and viruses.5 At high concentrations the smoke causes ocular and upper respiratory tract irritation in health care personnel. Smoke evacuators should be used and the various filters and absorbers used in smoke evacuators should be replaced on a regular basis. These materials should be disposed of with other biohazardous waste.5

Pacemaker Problems

The use of bipolar forceps or true electrocautery (with heated wire) are the preferred options of experienced cutaneous surgeons when electrosurgery is required in a patient with a pacemaker or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD).6 Routine precautions included utilizing short bursts of less than 5 seconds (71%), use of minimal power (61%), and avoiding use around the pacemaker or ICD (57%).6 One hundred sixty cutaneous surgeons reported the following complications: reprogramming of a pacemaker (six patients), firing of an ICD (four patients), asystole (three patients), bradycardia (two patients), depleted battery life of a pacemaker (one patient), and an unspecified tachyarrhythmia (one patient). Overall this was a low rate of complications (0.8 case/100 years of surgical practice), with no reported significant morbidity or mortality.6 Bipolar forceps were utilized by 19% of respondents and were not associated with any incidences of interference.6

Treating Specific Lesions

Benign Lesions

Angiomas (Cherry)

Topical or local anesthesia with epinephrine is often used if the lesions are greater than 4 mm. Larger cherry angiomas should be anesthetized and shaved off first before lightly electrodesiccating the base. Smaller cherry angiomas do not require anesthesia and can be lightly touched with the ball electrode on a low setting. The Hyfrecator is used on low at 2 to 2.5 W (Figure 14-17A). The Surgitron is used on 2 W of coagulation with the ball electrode (Figure 14-17B). The char can be wiped off with gauze or a curette. If red tissue remains, gently and briefly tap the electrode tip on the area again.

Condyloma Acuminata

If there are multiple, small condylomata, it may be prudent to initiate cryosurgery or topical treatments. In the office, this may include trichloroacetic acid, which is inexpensive, quick, and effective. The patient may also be sent home with a prescription for podofilox, a purified podophyllin preparation (Condylox), or imiquimod (Aldara), but these treatments are expensive and require patient compliance. Cryosurgery is an alternative (see Chapter 15, Cryosurgery). For small flatter lesions, curettement using a sharp 3-mm disposable curette works well. Condyloma acuminata can be successfully and easily treated with electrosurgery using either a cutting or a desiccation method. The cutting mode and large loop are especially beneficial for extensive and/or large lesions. Laser ablation is another option albeit the equipment is expensive.

The unit should be set for pure cutting with the power set based on the ESU and the loop size (see Tables 14-1 to 14-3). The condyloma should be “debulked” on the first pass and then the edges should be lightly “feathered” to ensure there is no remaining tissue and to blend the treated skin into the surrounding normal tissue. A common error is to go too deeply with the loop. Use caution. The penile skin is extremely thin and the RF loops cut very fast. Going too deeply will not only increase bleeding but also the secondary scarring. The same can happen with the vulvar and perianal tissues. If one attempts to perform a flat shave with a surgical blade, one often finds it difficult to cut on the mobile skin and bleeding readily obscures the operating field. That is the beauty of high-frequency electrosurgical removal: limited if any bleeding, controllable depth, minimal tissue destruction, and little scarring even with larger lesions. Using magnification during removal enhances all of these benefits even more.

The sequence for removal of a condyloma using high-frequency electrosurgery is as follows:

Neurofibromas

Neurofibromas are soft, benign tumors that are elevated above the skin surface (see Figure 33-30 in Chapter 30, Procedures to Treat Benign Conditions). Smaller lesions can appear to be nonpigmented nevi. However, if shaved off, a gelatinous material appears at the base, which is classic for neurofibromas and indicates the need for further treatment. Patients may request removal for cosmetic purposes, because they exist in areas of friction or trauma or because of fear that the lesion is not benign. Two possible electrosurgical methods for removal include (1) a shave with a scalpel and then electrocoagulation of the gelatinous residual or (2) a shave with a wire loop electrode using cutting and coagulation (blended) current going progressively deeper until the lesion is removed. In both instances, it is often easier to curette out the base, which often goes surprisingly deep, followed by the electrosurgery. For lesions over a centimeter in diameter, excision with suture closure provides faster healing with less scarring.

Nevi (Moles) Benign

All excised pigmented lesions regardless of method used for removal should be sent to the pathologist. Many nevi are removed because of cosmetic concerns or because of repeated trauma to them (e.g., under a bra strap, where routine shaving cuts them on the face or legs). When a lesion is almost certainly not a melanoma, a shave removal can be performed safely (see below for recommended technique). With atypical-appearing nevi, one has to ask the question, “Could this be a melanoma?” If the response is “Yes, it certainly could be,” then biopsy for depth. If the response is that a melanoma is quite unlikely, then removal using a shave technique is preferred. Shave removal is quicker, less costly, provides an adequate diagnosis in the majority of instances, and results in less scarring providing an excellent cosmetic result, especially with the RF technique described here (see Chapter 8, Choosing the Biopsy Type).

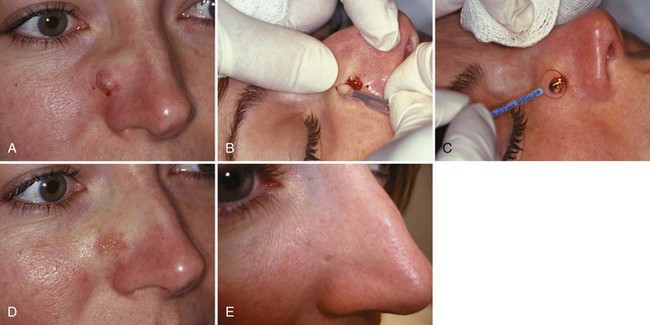

The following electrosurgical technique is excellent for the removal of presumed benign nevi with RF (Figure 14-19):

Pyogenic Granuloma

Pyogenic granulomas are very vascular benign tumors (Figure 14-20). They occur most commonly on the fingers, face, lips, and gingiva. Pyogenic granulomas often occur at the site of minor trauma and are more common in pregnancy. These vascular lesions are ideal for electrosurgical treatment.

In a randomized controlled study (RCT) comparing cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen versus curettage and electrodesiccation of patients with pyogenic granuloma, the curettage and electrodesiccation had the advantage of requiring fewer treatment sessions to achieve resolution and better cosmetic results.7

Before treatment, inject 1% lidocaine with epinephrine to cause blanching of the skin at the base of the lesion. Epinephrine is needed because of the extreme vascularity of these lesions. If the pyogenic granuloma is on a finger, start with a digital block with lidocaine and no epinephrine. Some physicians place a temporary tourniquet around the base of the finger to control bleeding during the procedure. If choosing this approach, the tourniquet may be left on for at least 30 minutes safely. (See page 217 for discussion of tourniquets.)

Wait at least a few minutes after the injection to gain the benefit of the epinephrine. Lab slips and forms can be filled out during this time. The elevated portion of the lesion is then shaved off with a scalpel blade. (Alternatively, a loop electrode using a cutting/coagulation current could have been used with the caution that it can easily penetrate too deeply, very quickly.) Send the specimen for histology to rule out the remote possibility that the lesion is an amelanotic melanoma. The base of the wound is curetted with a 3-0 to 5-0 dermal curette to remove the remaining tissue. Before electrocoagulating the base, compress the tissue with gauze to control bleeding. Pooled blood or active bleeding will diminish the efficacy of electrosurgery. In Figure 14-20, after blotting the blood away, the base is treated with electrodesiccation. (It may be necessary to use the higher power of electrocoagulation for these vascular lesions.) Further curettage and desiccation may be required a number of times to destroy the whole pyogenic granuloma and to stop the bleeding. If some tissue remains, the pyogenic granuloma will regrow.

Rhinophyma

Rhinophyma is a form of rosacea that can grossly disfigure the nose (Figure 14-21). In this case the bulbous tissue was also blocking the nostrils and impairing breathing. Patients are stared at in public places and may limit their activities to avoid public ridicule. The electrosurgical cutting devices provide an excellent treatment option for rhinophyma. Although the surgery is performed for more than cosmetic reasons, it is important to obtain prior authorization from the insurance company before proceeding with this procedure. It can be a difficult and time-consuming procedure so it is best to allocate 1 to 2 hours on the schedule. Payment is commensurate with the time invested. This is an advanced procedure and should be performed only when the clinician has significant experience with facial surgery and electrosection.

Appropriate-sized cutting loops are essential. The loops used for cervical LEEP procedures (Figure 14-13) are excellent for this purpose. Other large electrosurgical loops can also be used. Place the neutral plate below the patient’s head. A smoke evacuator is definitely needed and it helps to have two assistants. One will be needed to hold the smoke evacuator tubing and to make adjustments in the electrosurgical settings. The other assistant can help remove the strips of skin and apply pressure for hemostasis when needed.

Perform infraorbital blocks bilaterally before starting with the local anesthetic. See Chapter 3 for a guide to regional blocks. Then inject 1% lidocaine and epinephrine into the affected area (Figure 14-21B). Although this is the nose, it is crucial to have epinephrine to keep the bleeding to a minimum.

Start by shaving down the nose with the loop. The pure cutting setting with levels as high as 30 W may be needed. Move the loop across the nose in one long continuous motion (Figure 14-21C). The assistant can hold the strip of skin up while you finish the pass (Figure 14-21D). Large white areas of sebaceous hyperplasia will be encountered (Figures 14-21E and F). Shape the nose and compare the sides for symmetry. Leave some definition of the nasal alae as they come off from the central nose. This procedure literally sculpts a new nose. The abnormal tissue will be soft and cut easily. Do not remove too much tissue. A second procedure to remove more tissue can be done if needed.

Hemostasis can be obtained along the way with pressure from gauze and electrocoagulation. A bipolar forceps attached to the same electrosurgical unit may be ideal. Alternatively, change the loop electrode over to the ball electrode as needed for hemostasis (Figure 14-21G). If a second electrosurgical unit is in the room, that unit could be dedicated to hemostasis while keeping the RF cutting unit for the loop only.

At the end of the procedure (Figure 14-21H) cover the nose with petrolatum and gauze. One way to keep the gauze in place is to wrap a long gauze around the back of the head. Send the patient home with a prescription for a pain medication such as hydrocodone and acetaminophen. Have the patient return in 2 days for a wound check to make sure there are no signs of infection and that bleeding is not a problem. Moist healing postoperative care is essential.

These patients are very appreciative because this procedure often provides a new life free from the fear of going out in public (Figure 14-21I).

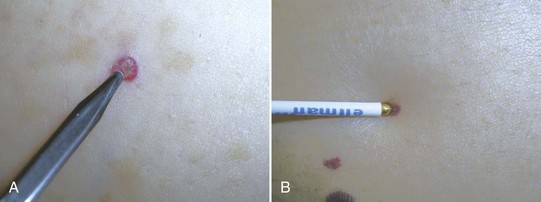

Sebaceous Hyperplasia

If the diagnosis is certain because the sebaceous hyperplasia is typical, the condition can be treated with tissue destruction using cryosurgery or electrodesiccation. Either of these approaches will not yield a specimen for pathology. When using electrodesiccation, a low-power setting should be used to avoid scarring (Figure 14-22).

Seborrheic Keratosis

When dealing with a classic, thin seborrheic keratosis, another technique is to lightly fulgurate the lesion and then wipe it off with a gauze or curette. Because this does not provide tissue for pathology, this approach should not be used if the lesion has suspicious features (i.e., may be a melanoma). The advantage to this technique is that the desiccated seborrheic keratosis is easily removed from the skin below, without going deeper than necessary (Figure 14-23). This allows for good control of the depth of removal and can minimize scarring. However, these lesions are very hyperkeratotic and thus quite dry often making any electrosurgical attempts at removal more difficult unless they are hydrated first using water-moistened 4 × 4 gauze.

FIGURE 14-23 Electrosurgery can be used in conjunction with a curette to superficially remove seborrheic keratoses.

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

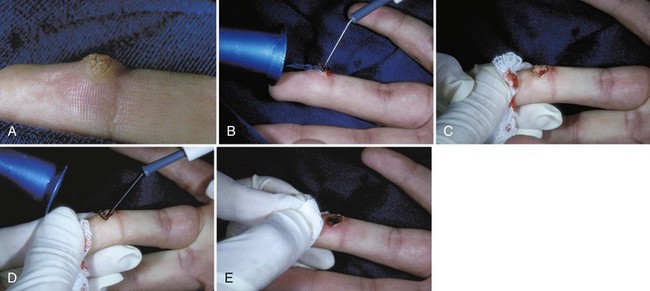

When using radiosurgery to shave these lesions, it may help to outline the lesion with a surgical pen. A large round loop electrode can be used to shave off the lesion with a single initial pass using a pure cutting setting. See Tables 14-1 to 14-3 for power settings. The skin can be smoothed, using the loop like an artist painting with a brush, while keeping the electrode at a 90-degree angle to the skin surface. Gentle strokes are used to feather the edges of the lesion into the normal skin. A moist 4 × 4 gauze is used between passes of the electrode to remove tissue and moisten the skin. Because the electrical current kills potential infectious organisms, there is no need to use sterile water or saline to moisten the gauze; tap water is fine. Remember that radiosurgery, if set at too high of a power or with any coagulation setting, may still cause more tissue destruction than just a surgical blade, so that the chance of hypopigmentation or scarring may be greater. However, using a combined technique like that described for a nevus above optimizes ease of removal while limiting complications.

Skin Tags (Acrochordons)

The eyelid is a location where it is important to be very careful when using chemicals for hemostasis. When used carefully, light electrodesiccation allows for hemostasis without endangering the eye. For radiosurgery of a skin tag, a loop electrode with a cut and coagulation setting of 4 to 6 W should be used after lidocaine and epinephrine are injected first. The skin tag should be shaved off with the loop alone or grasped with the forceps in the loop first (Figure 14-24).

Telangiectasias

Telangiectasias (Figure 14-25) are fine veins (“spider angiomas,” “spider veins”) that occur commonly on the face and legs. Laser treatment can be effective but is more costly and is not as readily available as sclerotherapy or electrosurgery. Very fine veins of the lower extremities may do well with laser but generally, sclerotherapy is the treatment of choice for lesions 1 to 5 mm that are extensive. Unless the veins are very focal on the legs, RF/electrosurgery does not perform well. Facial veins are usually more limited and, without the hydrostatic pressure that is present in the legs, treatment with electrosurgery can provide excellent results. Fine telangiectasias on the face are the best candidates since anything over a diameter of 1 mm is likely to bleed and persist. As with all procedures, discuss the risks and benefits of electrosurgical treatment and obtain informed consent before proceeding. Treatment of these lesions is generally for cosmetic reasons so it is even more important to review the various options and the possible complications.

Warts (Verruca Vulgaris)

In general, most warts can be treated effectively and easily with cryotherapy as described in Chapter 15 or with intralesional injection as discussed in Chapter 16. Patients may even use topical agents effectively at home. However, some warts are refractory to all treatments. Also, if the warts are small (a few millimeters) and there are only a few lesions, electrosurgery has the advantage of allowing the physician to obtain good cure rates with a single in-office treatment. Electrosurgery offers the advantage that the complete removal of the wart can be seen at the time of treatment. With cryotherapy, one must base treatment on the size of the ice ball halo, the freezing time, and most importantly the thaw time. Cryotherapy and intralesional injection methods are more likely to require multiple visits for treatment. Cryotherapy may be more painful in the days that follow the treatment and it frequently leads to an open wound (as does electrosurgery) or a blister.

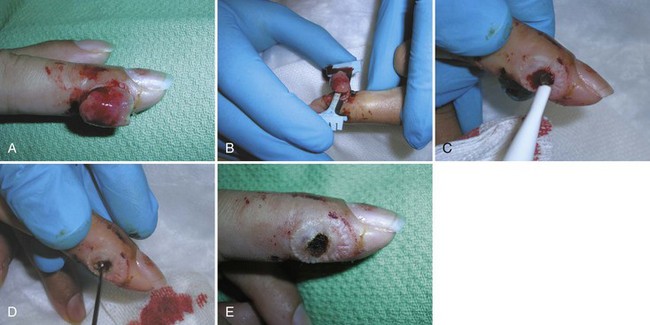

Electrosurgery of warts always requires local anesthesia. If treating the digits (Figure 14-26), local infiltration with epinephrine-free anesthetic or a digital block should be used. In some cases, local infiltration with lidocaine and epinephrine can be used if the digital artery is avoided. For other locations, the use of epinephrine in the local can aid in obtaining a blood-free field. Fulguration or electrodesiccation/coagulation/hemostasis settings are used to destroy the wart (Figure 14-26B). Refer to Tables 14-1 to 14-3 for power settings. The ball or pointed tip electrode is generally used. With smaller lesions, desiccated tissue is then wiped away with a moist gauze or a curette (Figure 14-26C). If any wart tissue remains, the remaining tissue should receive additional electrosurgery and be wiped away until the final deep layer shows a uniform clear dermis (Figures 14-26D and E). The base of the lesion, however, is often charred by the treatment obscuring the underlying tissue so this needs to be wiped off to inspect the base. Warts are an epidermal lesion so care should be used not to penetrate through the dermis.

Malignant Lesions

If the nature of a lesion is in doubt, it is always best to biopsy it before definitive treatment. As one gains experience, some lesions may be able to be treated on the day of the first evaluation when they have a “classic” clinical history, appearance, and “feel.” All tissue specimens are best sent for histologic confirmation whether they were biopsied previously or not. Shave or curettement biopsies are generally adequate for NMSCs. If the lesion is potentially a melanoma, a full-thickness biopsy should be performed with no further electrosurgical treatment. Performing wide excisions on a “presumed” diagnosis is costly, creates more potential for complications, and often will over- or undertreat a lesion (see Chapter 8, Choosing the Biopsy Type).

Electrodesiccation and Curettage

One study compared recurrence rates of 268 consecutive primary nonmelanoma tumors (BCCs and SCCs) treated by surgical excision or ED&C. The recurrence rates between the two types of treatment were not found to be significantly different.8 A meta-analysis of all studies reporting recurrence rates of BCC between 1947 and 1987 reported a 5-year recurrence rate of approximately 8% for ED&C.9

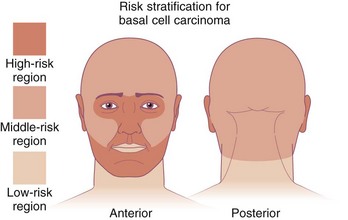

An analysis of recurrence rates of 2314 previously untreated BCCs removed by ED&C showed that increasing lesion diameter, high-risk, and middle-risk anatomic sites were independent risk factors for high recurrence rates.10 From 1973 to 1982 the following recurrence rates were found (Figure 14-27):

FIGURE 14-27 Risk stratification for basal cell carcinoma on the face and head.

(From Robinson J, Hanke W, Sengelmann R, Siegel D. Surgery of the Skin: Procedural Dermatology, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2010.)

The authors concluded that BCCs less than 6 mm in diameter, regardless of anatomic site, as well as selected larger BCCs depending on their anatomic site, are effectively treated by ED&C.10

Recurrence rates of primary NMSCs treated by excision versus ED&C ×3 were studied in a private dermatology practice. Tumors up to 2 cm in size were included. One percent of excised tumors recurred, whereas 3% treated with ED&C did. This study found the recurrence rates to be essentially the same in spite of the fact that they used electrosurgery to treat tumors larger than generally recommended. ED&C was quicker, less costly, has fewer complications, and the scars were often less.8

Organ transplant recipients frequently develop multiple SCCs. In one study, appropriately selected low-risk SCCs in 48 organ transplant recipients were treated by ED&C. Only histologically confirmed SCCs were considered in this study.11 The mean follow-up time was 50 months, and 13 residual or recurrent SCCs were observed in 10 patients. The overall rate of residual or recurrent SCCs was 6%, with 7% for SCCs on the dorsum of the hands or fingers, 11% for SCCs on the head and neck, 0% for the forearms, and 5% for the remaining non–sun-exposed areas (shoulder, legs). In organ transplant recipients with many SCCs, ED&C can be a safe therapy for appropriately selected low-risk SCCs, with an acceptable cure rate.11

Using ED&C with BCC or SCC: Step-by-Step Instructions

Learning the Techniques

Practicing Radiosurgery

Follow these guidelines for practicing with the Ellman Surgitron and other high-frequency units:

One method that can be used to test ESU cutting settings on the patient without consequences to healing is to remove the tissue of concern with a circle before finishing the ellipse with two additional triangles. This circle will not be the area that needs to heal for the patient and therefore will allow for evaluation of the settings before the final cuts are made (Figure 14-29).

Coding and Billing Pearls

Electrosurgery is one modality used throughout dermatology for diverse procedures. When electrosurgery is used for tissue destruction, coding is based on the skin destruction codes found in Tables 38-5, 38-6, and 38-11 of Chapter 38, Surviving Financially. Benign and premalignant tissue destruction has essentially been divided into three types of CPT codes based on these diagnoses:

(Note that laser destruction of cutaneous vascular lesions has separate codes.)

The general destruction codes shown in Box 14-2 are usually independent of the method of destruction and the location of the lesions. However, for destructions of benign lesions, certain specific parts of the body are reimbursed at a higher rate including the anus, penis, vulva, vagina, and eyelid. The CPT codes and typical fees charged for these are detailed in Table 38-6 of Chapter 38. Do not forget to use these codes because they do pay better than 17110 and 17111. These specific location codes are not based on the exact number of lesions and a single lesion may be reimbursed the same as many lesions.

Box 14-2 CPT General Destruction Codes

Note that malignant skin destruction codes (Table 38-11 in Chapter 38) are based on size and location of the cancer and not on the type of skin cancer. Electrodesiccation and curettage of BCCs and SCCs are reimbursed based on these codes.

1. Calero L, Brusis T. [Laryngeal papillomatosis—first recognition in Germany as an occupational disease in an operating room nurse]. Laryngorhinootologie. 2003;82:790-793.

2. Sawchuk WS, Weber PJ, Lowy DR, Dzubow LM. Infectious papillomavirus in the vapor of warts treated with carbon dioxide laser or electrocoagulation: detection and protection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:41-49.

3. Bigony L. Risks associated with exposure to surgical smoke plume: a review of the literature. AORN J. 2007;86:1013-1020.

4. Mosterd K, Krekels GA, Nieman FH, et al. Surgical excision versus Mohs’ micrographic surgery for primary and recurrent basal-cell carcinoma of the face: a prospective randomised controlled trial with 5-years’ follow-up. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:1149-1156.

5. Control of smoke from laser/electric surgical procedures. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Appl Occup Environ Hyg. 1999;14:71.

6. El-Gamal HM, Dufresne RG, Saddler K. Electrosurgery, pacemakers and ICDs: a survey of precautions and complications experienced by cutaneous surgeons. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:385-390.

7. Ghodsi SZ, Raziei M, Taheri A, et al. Comparison of cryotherapy and curettage for the treatment of pyogenic granuloma: a randomized trial. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:671-675.

8. Werlinger KD, Upton G, Moore AY. Recurrence rates of primary nonmelanoma skin cancers treated by surgical excision compared to electrodesiccation-curettage in a private dermatologic practice. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:1138-1142.

9. Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CLJr. Long-term recurrence rates in previously untreated (primary) basal cell carcinoma: implications for patient follow-up. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15:315-328.

10. Silverman MK, Kopf AW, Grin CM, et al. Recurrence rates of treated basal cell carcinomas. Part 2: curettage-electrodesiccation. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1991;17:720-726.

11. de Graaf YG, Basdew VR, van Zwan-Kralt N, et al. The occurrence of residual or recurrent squamous cell carcinomas in organ transplant recipients after curettage and electrodesiccation. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:493-497.

Pfenninger JL. Radiofrequency surgery (modern electrosurgery) (Chap 30). In Pfenninger JL, Fowler GC, editors: Pfenninger and Fowler’s Procedures for Primary Care, 3rd ed, Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier, 2011.

Soon SL, Washington CV. Curettage and electrodesiccation. In Robinson JK, Hanke CW, Sengelmann RD, Siegel DM, editors: Surgery of the Skin, 2nd ed, New York: Elsevier, 2010.