36 Complications

Postprocedural Adverse Effects and Their Prevention

The incidence of complications can be decreased with good procedural techniques and early recognition of problems before they become severe. Potential adverse effects and complications of skin procedures can be categorized by the time when they occur, as listed in Box 36-1.

Box 36-1 Potential Adverse Effects and Complications of Skin Procedures

An informed consent form covering the potential complications should be discussed with and signed by the patient. The informed consent form should cover the items in the list above that pertain to the surgical procedure for the specific site and patient. No absolute guarantees of cosmetic results should be made. See Chapter 1, Preoperative Preparation, and the sample consent form titled Disclosure and Consent: Medical and Surgical Procedures in Appendix A.

Review of the Literature

In a prospective study of 3788 dermatologic surgery procedures, there were 236 complications (6%).1 Most complications were minor and bleeding was the most common (3%). Vasovagal syncope was the main anaesthetic complication (51 of 54). Infectious complications occurred in 79 patients (2%). Complications requiring additional antibiotic treatment or repeat surgery accounted for only 22 cases (1%). No statistically significant correlation was found with the characteristics of the dermatologists, especially with respect to their training or amount of surgical experience. Multivariate analysis showed that anaesthetic or hemorrhagic complications were independent factors that predicted infectious complications. Patients on anticoagulants or immunosuppressant medications, type of procedure performed and duration exceeding 24 minutes were independent factors that predicted hemorrhagic complications.1

Two years later, the same group published a study of 3491 dermatologic surgical procedures describing postoperative infections in 67 patients (1.9%), with superficial suppuration accounting for 92.5% of surgical site infections.2 The incidence was higher in the excision group with a reconstructive procedure (4.3%) than in excisions alone (1.6%). Infection control precautions varied according to the site of the procedure; multivariate analysis showed that hemorrhagic complications were an independent factor for infection in both types of surgical procedures. Male gender, immunosuppressive therapy, and not wearing sterile gloves were independent factors for infections occurring following excisions with reconstruction.2

Dixon et al. performed a prospective study of 5091 lesions (predominantly nonmelanoma skin cancer) treated on 2424 patients.3 None of the patients was given prophylactic antibiotics, and warfarin or aspirin was not stopped. The overall infection rate was 1.47%. Individual procedures had the following infection incidence:

Surgery below the knee had an infection incidence of 6.9% (31/448) and groin excisional surgery had an infection incidence of 10% (1/10). Patients with diabetes, those on warfarin and/or aspirin, and smokers showed no difference in infection incidence. In conclusion, all procedures below the knee, wedge excisions of the lip and ear, all skin grafts, and lesions in the groin had the highest rates of infection and the authors suggest considering wound infection prophylaxis in these patients.3

In a prospective study of hospitalized patients undergoing diagnostic skin biopsies, infection, dehiscence, and/or hematoma occurred in 29% of the patients.4 Complications occurred significantly more frequently when biopsies were performed below the waist, in the ward compared with the outpatient operating room, in smokers, and in those taking corticosteroids.4 In addition, elliptical incisional biopsies developed complications more frequently when subcutaneous sutures were not used.4

In one study of 1400 Mohs procedures, 25 infections were identified.5 Statistically significant higher infection rates were found in patients with cartilage fenestration with second intent healing and patients with melanoma. There was no statistical difference in infection rates with all other measured variables including the use of clean, nonsterile gloves rather than sterile gloves during the tumor removal phase of surgery.5 Sterile gloves were used by all surgeons during the repair phase.

In 2008, an advisory statement on antibiotic prophylaxis in dermatologic surgery was published.6 Expert consensus based on a small number of studies suggests that antibiotics for the prevention of surgical site infections may be indicated for procedures on the lower extremities or groin, for wedge excisions of the lip and ear, skin flaps on the nose, skin grafts, and for patients with extensive inflammatory skin disease.6 Also, patients with high-risk cardiac conditions, and a defined group of patients with prosthetic joints at high risk for hematogenous total joint infection, should be given prophylactic antibiotics (to prevent bacterial endocarditis) when the surgical site is infected or when the procedure involves breach of the oral mucosa.6

Bleeding

The most likely complication of dermatologic surgery is bleeding (accounting for half of a 6% complication rate).1 Larger surgeries with more undermining are at highest risk of bleeding complications. Good intraoperative hemostasis, appropriate suturing techniques, and pressure dressings can help minimize bleeding complications. Aspirin can cause excessive bleeding during surgery if not stopped 2 weeks before surgery. NSAIDs can also cause excessive bleeding if not stopped 2 days before surgery. Warfarin (Coumadin) also increases the risk of bleeding intraoperatively and postoperatively (Figure 36-1). That said most clinicians would not postpone skin surgery because the patient has recently taken aspirin or an NSAID. Often the risk of stopping warfarin or aspirin is greater to the patient (such as stroke) than dealing with the bleeding issues. In fact, in a study of 2424 patients undergoing dermatologic surgery, the warfarin or aspirin was not stopped in any of these patients.3 For further information on the risks and benefits of anticoagulation before surgery see Chapter 1 on preoperative preparation.

Swelling and Bruising

Patients should be warned that surgery performed around the nose or forehead can cause swelling and bruising around the eyes (Figure 36-2). It is even possible that the eyes may swell shut. The use of ice may help prevent some of this edema if it is used during the first few hours after surgery. The lips can also stay swollen for many weeks or months after surgery.

Infection

The highest risks for infections involve procedures below the knee or in the groin, wedge excisions of the lip and ear, and all skin flaps and grafts.3 Patients who smoke and those taking oral corticosteroids are at higher risk of infection.4 The 2008 AAD advisory statement states that prophylactic antibiotics may be indicated for:

One study describes the use of intraoperative injectable clindamycin to prevent wound infections. In a total of 1030 consecutive patients who underwent Mohs surgery, prior to reconstruction, patients were randomly assigned to receive either intraincisional buffered lidocaine with epinephrine containing clindamycin or buffered lidocaine with epinephrine without clindamycin.7 The surgical wounds that received the clindamycin had a lower rate of infection than those that did not. The authors concluded that the results of their study support the efficacy of single-dose preoperative intraincisional antibiotic treatment for dermatologic surgery.7

Wound infections may initially be subtle and appear like the erythema seen around a healing incision. If you are uncertain about a possible infection, pressure applied with the gloved hand can be used to express pus hidden below the skin (Figure 36-3). If no pus is expressed but the suspicion for infection is great, consider removing a few stitches early and applying some pressure with a cotton-tipped applicator to detect pus. Send all purulent exudates for culture in this time when methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is so prevalent (Figure 36-3). The choice of antibiotic should consider MRSA as a possible cause of any wound infection.

FIGURE 36-3 Erythema and swelling at the site of a wound infection caused by MRSA.

(Courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

A wound infection may present with the classic signs of redness, warmth, and pain. The patient may have a slight fever, and pus may be expressed from the wound. These symptoms usually become obvious around 5 to 7 days postoperatively or at the time of suture removal (Figure 36-4). Infections can manifest at postoperative day 2 to 4. If a patient has any complaints, it is best to examine the wound for evidence of infection. If the wound is tender and fluctuant, removal of one or more sutures to allow drainage will speed up resolution of the infection. Empirical antibiotic treatment in adults may start with cephalexin 500 mg tid–qid or clindamycin 300 mg tid in the penicillin-allergic patient. If the patient has a known history of MRSA infections, consider starting with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or clindamycin. Of course, culture results in the coming days should be reviewed and may necessitate changing antibiotics.

FIGURE 36-4 Purulence and erythema at the site of a wound infection near the groin.

(Courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

Suture Reactions

Suture reactions are frequently mistaken for infections and must be differentiated from them. These may arise in areas where buried sutures have been placed and can present as a small pustule or erosion in the suture line (Figure 36-5). The patient can complain of a “pimple” on the suture line or a piece of suture extruding from the incision line. This can occur when a buried suture is placed too close to the skin surface. Purulent material from these sites is sterile.

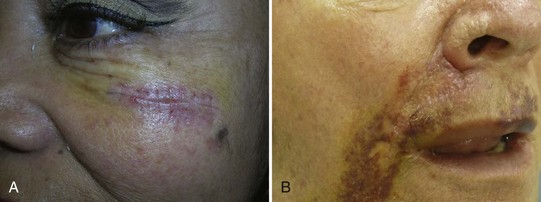

Scarring

Excessive or increased skin tension leads to a widened scar. This is the reason why buried sutures that decrease tension can improve cosmetic results. The increased skin tension in younger patients probably contributes to the widened scars seen in young patients compared with the narrow, fine scars seen in older patients. In Figure 36-6A, a widened scar is seen on a young woman’s arm years after the wide excision of a melanoma.

Allowing sutures to remain in place for too long can also increase scarring. Complications such as infection, necrosis, or dehiscence can increase scarring (Figure 36-6B). Excessive skin tension often leads to dehiscence and scarring. Infection or necrosis often leads to dehiscence. Dehiscence may be prevented by using good excision planning, undermining when necessary, and using deep absorbable sutures to decrease skin tension across a wound. Tying sutures too tightly can also cause scarring.

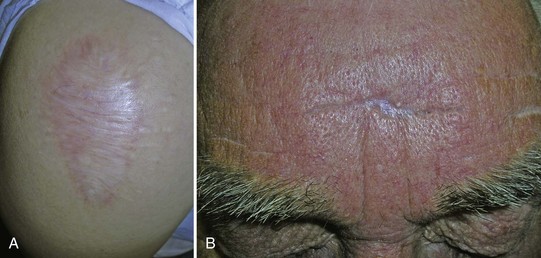

Hypopigmentation

Hypopigmentation is most likely to occur with the following procedures: cryosurgery, ED&C, and shave biopsies. Although it may be cosmetically worse in darker skinned persons, it can occur in anyone. Patients must be warned of this complication, which can be permanent. Cryotherapy to treat nonmelanoma skin cancers is likely to cause hypopigmentation because of the long freeze times that are used (Figure 36-7A). Even a simple shave excision can lead to hypopigmentation (Figure 36-7B).

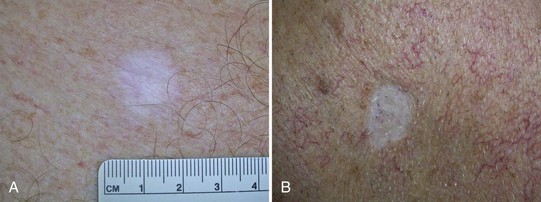

Flap Necrosis

A long, thin advancement flap in violation of the 3 : 1 ratio runs a high risk of distal flap tip necrosis (Figure 36-8). Patients who smoke excessively experience a much higher risk of flap tip necrosis and flap failure, and encouraging smoking cessation in the perioperative and postoperative course is helpful to achieve the best healing. The use of flaps must also be carefully weighed in those patients who may have underlying skin conditions that can lead to increased complications. Decreased flexibility and therefore impaired movement of skin can be seen in patients with extensive scarring from burns or other injuries, previous radiotherapy, or an underlying skin disease such as scleroderma. Decreased perfusion of skin leading to flap failure or infection can be seen in conditions such as diabetes mellitus, lung disease, or poor circulation secondary to atherosclerosis, especially in peripheral areas. Finally, the use of a flap may not be possible in patients with extremely thin skin that will not bear the stresses of flap movement such as elderly patients with extreme photodamage or long-term users of corticosteroids.

Nerve Damage

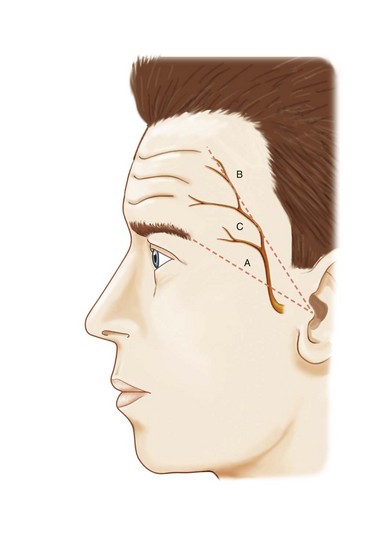

The temporal branch of the facial nerve can be damaged by surgery to the temple area. The nerve lies just below the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS). It can be difficult to see, and there is enough anatomic variation that it can be unpredictable in its location. One way to locate the nerve is to draw an imaginary line from the tragus to the eyebrow and another imaginary line from the tragus to the upper forehead wrinkle area (Figure 36-9). The area between these two lines within the temple area is where the temporal branch of the facial nerve is most superficial. If this nerve is cut, the patient will not be able to wrinkle the forehead because the innervation to the frontalis muscle is lost. The patient will also have a permanent inability to raise the upper eyelid (Figure 36-10). If any surgery is performed in this area, it is important to discuss this risk with the patient in the informed consent process. Also explain that the anesthesia after surgery alone can cause a temporary paralysis of this nerve (See Figure 11-2B in Chapter 11, The Elliptical Excision). When electrodesiccation and curettage is an option for a superficial skin cancer in this area, it may be a good choice. Mohs surgery is also an appropriate technique in this area because the tissue is removed layer by layer by an experienced surgeon.

FIGURE 36-9 Drawing of the temporal branch of the facial nerve.

(From Usatine RP. Skin Surgery: A Practical Guide. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1998.)

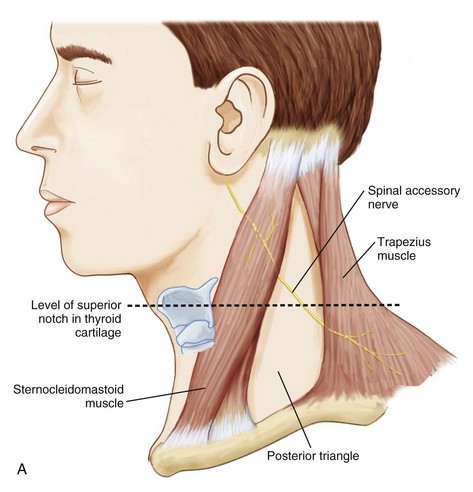

The spinal accessory nerve lies within the posterior triangle posterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle (Figure 36-11). The nerve can lie very superficially posterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle at the level of the thyroid cartilage notch. If this nerve is cut, the patient will lose major innervation to the trapezius muscle, resulting in impaired mobility of the scapula and shoulder.

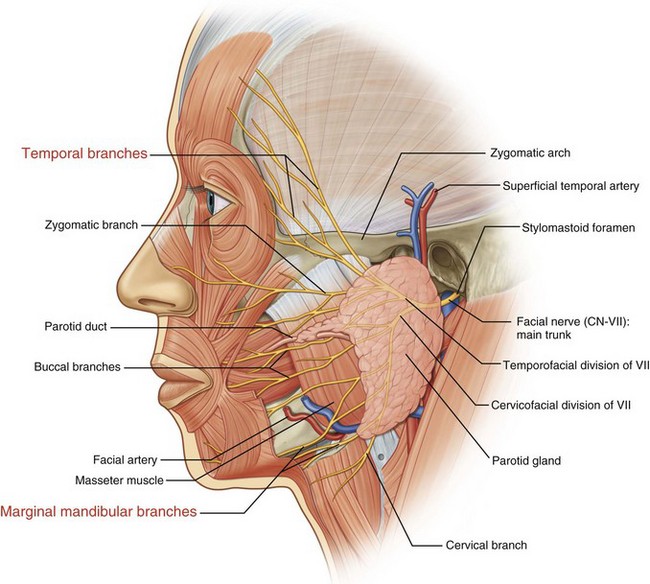

The marginal branch of the mandibular nerve (Figure 36-12) is the third nerve in the head and neck area that is vulnerable to injury during surgery. If it is cut then motor innervation to the depressor anguli oris and depressor labii inferioris can be lost. This results in a cosmetic deformity and imbalance in the appearance of the mouth, especially when the mouth is opened or when the patient wants to frown. Fortunately the nerve is not that superficial but each clinician operating in the area of the lower mandible should be aware of this branch of the facial nerve.

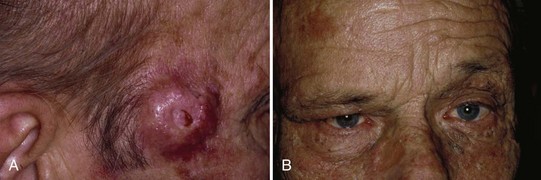

Recurrence of a Lesion or Skin Cancer

There is almost nothing in the practice of medicine that is a 100% guarantee. Mohs’ micrographic surgery for the removal of skin cancer has a cure rate of only 99% in primary skin cancers. Most other surgical techniques have cure rates of about 90%, depending on a number of factors. Lipomas, cysts, and nevi (especially if they are removed with a shave) can all recur. Although recurrent lesions may be considered a complication, the patient and clinician should both realize that recurrences will occur in a small percentage of cases. When a recurrent lesion develops, the lesion will usually need to be excised again. In Figure 36-13, a BCC recurred in the incision line after a large flap was placed on the neck.

FIGURE 36-13 Recurrent BCC at two sites along the area of a large flap repair to an extensive BCC on the neck.

(Courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

With regards to recurrence of BCC, one study showed that Mohs surgery had significantly fewer recurrences for the treatment of facial recurrent BCC than after standard surgical excision.8 However, there was no significant difference in recurrence of primary BCC between Mohs surgery and surgical excision in this study.8

Therefore, it is important to go over possible recurrence rates with patients before the final procedure is chosen. Even benign lesions like pyogenic granulomas can recur if all of the abnormal tissue is not removed at the time of surgery (Figure 36-14).

Making Mistakes

It is always important to express empathy to the patient and/or patient’s family after an adverse surgical event. “I am sorry” is an appropriate expression of empathy that does not express fault. In the book Sorry Works! the authors make a strong case for using the phrase “I’m sorry” along with disclosure, apologies, and relationships to prevent medical malpractice claims.10 They make the distinction that the phrase “I’m sorry” is an expression of empathy and “I apologize” is a communication that expresses responsibility along with empathy. They suggest to only apologize after due diligence has proven that a medical error occurred.

The authors make the case that it is better to disclose an error than to attempt to cover it up.10 They state that “people can actually live with mistakes but they do not accept or tolerate cover-ups.” They suggest the use of honesty, candor, and a real commitment to fix problems when something goes wrong. Showing empathy works by making a difficult situation a little better. To learn more about how to prevent lawsuits and improve relationships with patients during and after an adverse event, consult the book Sorry Works! and the website www.sorryworks.net.

1. Amici JM, Rogues AM, Lasheras A, et al. A prospective study of the incidence of complications associated with dermatological surgery. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:967-971.

2. Rogues AM, Lasheras A, Amici JM, et al. Infection control practices and infectious complications in dermatological surgery. J Hosp Infect. 2007;65:258-263.

3. Dixon AJ, Dixon MP, Askew DA, Wilkinson D. Prospective study of wound infections in dermatologic surgery in the absence of prophylactic antibiotics. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:819-826.

4. Wahie S, Lawrence CM. Wound complications following diagnostic skin biopsies in dermatology inpatients. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1267-1271.

5. Rhinehart MB, Murphy MM, Farley MF, Albertini JG. Sterile versus nonsterile gloves during Mohs micrographic surgery: infection rate is not affected. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:170-176.

6. Wright TI, Baddour LM, Berbari EF, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis in dermatologic surgery: advisory statement 2008. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:464-473.

7. Huether MJ, Griego RD, Brodland DG, Zitelli JA. Clindamycin for intraincisional antibiotic prophylaxis in dermatologic surgery. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1145-1148.

8. Mosterd K, Krekels GA, Nieman FH, et al. Surgical excision versus Mohs’ micrographic surgery for primary and recurrent basal-cell carcinoma of the face: a prospective randomised controlled trial with 5-years’ follow-up. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:1149-1156.

9. Thissen MR, Neumann MH, Schouten LJ. A systematic review of treatment modalities for primary basal cell carcinomas. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1177-1183.

10. Wojcieszak D, Saxton W, Finklestein M. Sorry Works! Disclosure, Apology, and Relationships Prevent Medical Malpractice Claims. Bloomington, IN: Author House; 2008.