Chapter 58 Effects of Toxins and Physical Agents on the Nervous System

Occupational Exposure to Organic Chemicals

Acrylamide

Clinical manifestations of acrylamide toxicity depend on the severity of exposure. Acute high-dose exposure results in confusion, hallucinations, reduced attention span, drowsiness, and other encephalopathic changes. A peripheral neuropathy of variable severity may occur after acute high-dose or prolonged low-level exposure. The neuropathy is a length-dependent axonopathy involving both sensory and motor fibers; some studies suggest that terminal degeneration precedes axonopathy and is the primary site of involvement, leading to a defect in neurotransmitter release (LoPachin, 2005). Hyperhidrosis and dermatitis may develop before the neuropathy is evident clinically in those with repeated skin exposure. Ataxia from cerebellar dysfunction also occurs and relates to degeneration of afferent and efferent cerebellar fibers and Purkinje cells. Neurological examination reveals distal sensorimotor deficits and early loss of all tendon reflexes rather than simply the Achilles reflex, which is usually affected first in most length-dependent neuropathies. Autonomic abnormalities other than hyperhidrosis are uncommon. Gait and limb ataxia are usually greater than can be accounted for by the sensory loss. With discontinuation of exposure, the neuropathy “coasts,” arrests, and may then slowly reverse, but residual neurological deficits are common. These consist particularly of spasticity and cerebellar ataxia; the peripheral neuropathy usually remits because regeneration occurs in the peripheral nervous system. No specific treatment exists. Studies in rats have shown that administration of FK506 to increase Hsp-70 expression may exert a neuroprotective effect and have therefore suggested that compounds eliciting a heat shock response may be useful for treating the neuropathy in humans (Gold et al., 2004).

Electrodiagnostic studies provide evidence of an axonal sensorimotor polyneuropathy. Workers exposed to acrylamide may be monitored electrophysiologically by recording sensory nerve action potentials, which are attenuated early in the course of the disorder, or by measuring the vibration threshold. Histopathological studies show accumulation of neurofilaments in axons, especially distally, and distal degeneration of peripheral and central axons. The role of neurofilament accumulation in the generation of axonal degeneration has been questioned (Stone et al., 2001). The large myelinated axons are involved first. The affected central pathways include the ascending sensory fibers in the posterior columns, the spinocerebellar tracts, and the descending corticospinal pathways. Involvement of postganglionic sympathetic efferent nerve fibers accounts for the sudomotor dysfunction. Measurement of hemoglobin-acrylamide adducts may be useful in predicting the development of peripheral neuropathy.

Carbon Disulfide

Long-term exposure to carbon disulfide may lead also to extrapyramidal (parkinsonian) or pyramidal deficits, impaired vision, absent pupillary and corneal reflexes, optic neuropathy, and a characteristic retinopathy. A small-vessel vasculopathy may be responsible (Huang, 2004). Neuroimaging may reveal cortical—especially frontal—atrophy, as well as lesions in the globus pallidus and putamen. A clinical or subclinical polyneuropathy develops after exposure to levels of 100 to 150 ppm for several months or to lesser levels for longer periods and is characterized histologically by focal axonal swellings and neurofilamentary accumulations.

Carbon Monoxide

Occupational exposure to carbon monoxide occurs mainly in miners, gas workers, and garage employees. Other modes of exposure include poorly ventilated home heating systems, stoves, and suicide attempts. The neurotoxic effects of carbon monoxide relate to intracellular hypoxia. Carbon monoxide binds to hemoglobin with high affinity to form carboxyhemoglobin; it also limits the dissociation of oxyhemoglobin and binds to various enzymes. Acute toxicity leads to headache (Hampson and Hampson, 2002), disturbances of consciousness, and a variety of other behavioral changes. Motor abnormalities include the development of pyramidal and extrapyramidal deficits. Seizures may occur, and focal cortical deficits sometimes develop. Treatment involves prevention of further exposure to carbon monoxide and administration of pure or hyperbaric oxygen, although the evidence is conflicting regarding the utility of hyperbaric oxygen in this setting (Buckley et al., 2005). Seizures may complicate hyperbaric oxygen therapy (Sanders et al., 2009). Neurological deterioration may occur several weeks after partial or apparently full recovery from the acute effects of carbon monoxide exposure, with recurrence of motor and behavioral abnormalities. The degree of recovery from this delayed deterioration is variable; full or near-full recovery occurs in some instances, but other patients lapse into a persistent vegetative state or severe parkinsonism. Neuroimaging may show lesions in the globus pallidus and elsewhere.

Hexacarbon Solvents

The hexacarbon solvents, n-hexane and methyl n-butyl ketone, are both metabolized to 2,5-hexanedione, which targets proteins required for the maintenance of neuronal integrity (Spencer et al., 2002) and is responsible in large part for their neurotoxicity. This neurotoxicity is potentiated by methyl ethyl ketone, which is used in paints, lacquers, printer’s ink, and certain glues. n-Hexane is used as a solvent in paints, lacquers, and printing inks and is used especially in the rubber industry and in certain glues. Workers involved in the manufacturing of footwear, laminating processes, and cabinetry, especially in confined, unventilated spaces, may be exposed to excessive concentrations of these substances. Methyl n-butyl ketone is used in the manufacture of vinyl and acrylic coatings and adhesives and in the printing industry. Exposure to either of these chemicals by inhalation or skin contact leads to a progressive distal sensorimotor axonal polyneuropathy; partial conduction block may also occur (Pastore et al., 2002). Optic neuropathy or maculopathy and facial numbness also have followed n-hexane exposure. The neuropathy is related to a disturbance of axonal transport, and histopathological studies reveal giant multifocal axonal swelling and accumulation of axonal neurofilaments, with distal degeneration in peripheral and central axons. Myelin retraction and focal demyelination are found at the giant axonal swellings.

Methyl Bromide

Treatment is symptomatic and supportive. Hemodialysis may also be helpful in removing bromide from the blood (Yamano et al., 2001). Chelating agents are of uncertain utility.

Organophosphates

Organophosphates are used mainly as pesticides and herbicides but are also used as petroleum additives, lubricants, antioxidants, flame retardants, and plastic modifiers. Most cases of organophosphate toxicity result from exposure in an agricultural setting, not only among those mixing or spraying the pesticide or herbicide but also among workers returning prematurely to sprayed fields. Absorption may occur through the skin, by inhalation, or through the gastrointestinal tract. Organophosphates inhibit acetylcholinesterase by phosphorylation, with resultant acute cholinergic symptoms, with both central and neuromuscular manifestations. Symptoms include nausea, salivation, lacrimation, headache, weakness, and bronchospasm in mild instances and bradycardia, tremor, chest pain, diarrhea, pulmonary edema, cyanosis, convulsions, and even coma in more severe cases. Death may result from respiratory or heart failure. Treatment involves intravenous (IV) administration of pralidoxime (1 g) together with atropine (1 mg) given subcutaneously every 30 minutes until sweating and salivation are controlled. Pralidoxime accelerates reactivation of the inhibited acetylcholinesterase, and atropine is effective in counteracting muscarinic effects, although it has no effect on the nicotinic effects, such as neuromuscular cholinergic blockade with weakness or respiratory depression. It is important to ensure adequate ventilatory support before atropine is given. The dose of pralidoxime can be repeated if no obvious benefit occurs, but in refractory cases it may need to be given by IV infusion, the dose being titrated against clinical response. Functional recovery may take approximately 1 week, although acetylcholinesterase levels take longer to reach normal levels. Measurement of paraoxonase status may be worthwhile as a biomarker of susceptibility to acute organophosphate toxicity; this liver and serum enzyme hydrolyzes a number of organophosphate compounds and may have a role in modulating their toxicity (Costa et al., 2005).

Certain organophosphates cause a delayed polyneuropathy that occurs approximately 2 to 3 weeks after acute exposure even in the absence of cholinergic toxicity. In the past, contamination of illicit alcohol with triorthocresyl phosphate (“Jake”) led to large numbers of such cases. There is no evidence that peripheral nerve dysfunction follows prolonged low-level exposure to organophosphates (Lotti, 2002). Paresthesias in the feet and cramps in the calf muscles are followed by progressive weakness that typically begins distally in the limbs and then spreads to involve more proximal muscles. The maximal deficit usually develops within 2 weeks. Quadriplegia occurs in severe cases. Although sensory complaints are typically inconspicuous, clinical examination shows sensory deficits. The Achilles reflex is typically lost, and other tendon reflexes may be depressed also; however, in some instances, evidence of central involvement is manifested by brisk tendon reflexes. Cranial nerve function is typically spared. With time, there may be improvement in the peripheral neuropathy, but upper motor neuron involvement then becomes unmasked and often determines the prognosis for functional recovery. There is no specific treatment to arrest progression or hasten recovery. Electrodiagnostic studies reveal an axonopathy with partial denervation of affected muscles and small compound muscle action potentials but normal or only minimally reduced maximal motor conduction velocity.

The delayed syndrome follows exposure only to certain organophosphates such as triorthocresyl phosphate, leptophos, trichlorfon, and mipafox. The neurological disturbance relates in some way to phosphorylation and inhibition of the enzyme, neuropathy target esterase (NTE), which is present in essentially all neurons and has an uncertain role in the nervous system (Lotti and Moretto, 2005). In addition, “aging” of the inhibited NTE (loss of a group attached to the phosphorus, leaving a negatively charged phosphoryl group attached to the protein) must occur for the neuropathy to develop. The precise cause of the neuropathy is uncertain, however. No specific treatment exists to prevent occurrence of the neuropathy following exposure, but measurement of lymphocyte NTE has been used to monitor occupational exposure and predict the occurrence of neuropathy. Moreover, the ability of any particular organophosphate to inhibit NTE in hens may predict its neurotoxicity in humans.

Three other syndromes related to organophosphate exposure require brief comment. The intermediate syndrome occurs in the interval between the acute cholinergic crisis and the development of delayed neuropathy, typically becoming manifest within 4 days of exposure and resolving in 2 to 3 weeks (Guadarrama-Naveda et al., 2001). It reflects excessive cholinergic stimulation of nicotinic receptors and is characterized clinically by respiratory and bulbar symptoms as well as proximal limb weakness. Symptoms relate to the severity of poisoning and to prolonged inhibition of acetylcholinesterase activity but not to the development of delayed neuropathy. The syndrome of dipper’s flu refers to the development of transient symptoms such as headache, rhinitis, pharyngitis, myalgia, and other flulike symptoms in farmers exposed to organophosphate sheep dips. Vague sensory complaints (but no objective abnormalities on sensory threshold tests) may also occur (Pilkington et al., 2001). Whether these complaints relate to mild organophosphate toxicity is uncertain. Similarly uncertain is whether chronic effects (persisting behavioral and neurological dysfunction) may follow acute exposure to organophosphates. The occurrence of chronic symptoms in the absence of any episode of acute toxicity is unlikely. Evaluation of reports is hampered by incomplete documentation and the variety of agents to which exposure has often occurred. Carefully controlled studies may clarify this issue in the future.

Pyrethroids

Pyrethroids are synthetic insecticides that affect voltage-sensitive sodium channels. Type II (α-cyano) pyrethroids, which have enhanced insecticidal activity, also affect voltage-dependent chloride channels and, at high concentrations, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-gated chloride channels (Bradberry et al., 2005). Occupational or residential exposure is increasing, is mainly through the skin but may also occur through inhalation, and has led to paresthesias that have been attributed to repetitive activity in sensory fibers as a result of abnormal prolongation of the sodium current during membrane excitation. The paresthesias affect the face most commonly and are exacerbated by sensory stimulation such as scratching; they typically resolve within a day. Treatment is purely supportive. Coma and convulsions may result if substantial amounts of pyrethroids are ingested (Proudfoot, 2005).

Solvent Mixtures

In the 1970s, a number of reports from Scandinavia suggested that house painters, in particular, developed a disturbance of cognitive function that related to exposure to mixtures of organic solvents. However, further studies (including cases previously diagnosed with the disorder) have failed to validate the earlier reports, which in many instances were methodologically flawed. Furthermore, workers performing the same basic tasks in different companies have highly variable levels of solvent exposure, complicating the interpretation of published studies (Horstman et al., 2001). Because of these factors, the existence of so-called painter’s encephalopathy in those exposed to low levels of organic solvents for a prolonged period remains uncertain.

Styrene

Styrene is used for manufacturing reinforced plastic and certain resins. Occupational exposure occurs by the dermal or inhalation routes and is typically associated with exposure to a variety of other chemicals, thereby making it difficult to define the syndrome that occurs from styrene exposure itself. Exposure (inhalation or dermal) occurs particularly among those working in industries manufacturing or using styrene, those exposed to automobile exhaust or cigarette smoke, and those using photocopiers. Styrene may also be ingested in drinking water or certain foods. Further details and allowable limits are provided by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (2007). Acute exposure to high concentrations of styrene has led to cognitive, behavioral, and attentional disturbances. Less clear are the consequences of exposure to chronic low levels of styrene. Abnormalities in psychomotor performance have been reported, but there is little compelling evidence of persisting neurological sequelae in this circumstance. Visual abnormalities (impaired color vision and reduced contrast sensitivity) also occur.

Toluene

Toluene is used in a variety of occupational settings. It is a solvent for paints and glues and is used to synthesize benzene, nitrotoluene, and other compounds. Exposure, usually by inhalation or transdermally, occurs among workers laying linoleum, spraying paint, and working in the printing industry, particularly in poorly ventilated locations. Chronic high exposure may lead to cognitive disturbances and to central neurological deficits with upper motor neuron, cerebellar, brainstem, and cranial nerve signs and tremor (Filley et al., 2004). An optic neuropathy may occur, as may ocular dysmetria and opsoclonus. Disturbances of memory and attention characterize the cognitive abnormalities, and subjects may exhibit a flattened affect. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows cerebral atrophy and diffuse abnormalities of the cerebral white matter; symmetrical lesions may be present in the basal ganglia and thalamus and the cingulate gyri. Thalamotomy may ameliorate the tremor if it is severe. Lower levels of exposure lead to minor neurobehavioral disturbances.

Trichloroethylene

Trichloroethylene is an industrial solvent and degreaser that is used in dry cleaning and the manufacture of rubber. It also has anesthetic properties. Recreational abuse has occurred because it may induce feelings of euphoria. Acute low-level exposure may lead to headache and nausea, but claims that an encephalopathy follows chronic low-level exposure are unsubstantiated. Higher levels of exposure lead to dysfunction of the trigeminal nerve, with progressive impairment of sensation that starts in the snout area and then spreads outward. This has been particularly associated with rebreathing anesthetic circuits where the trichloroethylene is heated by the carbon dioxide absorbent. With increasing exposure, facial and buccal numbness is followed by weakness of the muscles of mastication and facial expression. Ptosis, extraocular palsies, vocal cord paralysis, and dysphagia may occur also, as may signs of parkinsonism (Gash et al., 2008) or an encephalopathy, but occurrence of a peripheral neuropathy is uncertain. The clinical deficit relates to neuronal loss in the cranial nerve nuclei and nigrostriatal dopaminergic system and degeneration in related tracts. With discontinuation of exposure, the clinical deficit generally resolves, sometimes over 1 to 2 years, but occasional patients are left with residual facial numbness or dysphagia.

Occupational Exposure to Metals

Arsenic

Arsenic poisoning can result from ingestion of the trivalent arsenite in murder or suicide attempts. Large numbers of persons in areas of India, Pakistan, and certain other countries are chronically poisoned from naturally occurring arsenic in ground water (Vahidnia et al., 2007). Traditional Chinese medicinal herbal preparations may contain arsenic sulfide and mercury and are a source of chronic poisoning. Uncommon sources of accidental exposure include burning preservative-impregnated wood and storing food in antique copper kettles. Exposure to inorganic arsenic occurs in workers involved in smelting copper and lead ores.

With acute or subacute exposure, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, hypotension, tachycardia, and vasomotor collapse occur and may lead to death. Obtundation is common, and an acute confusional state may develop. Arsenic neuropathy takes the form of a distal axonopathy, although a demyelinating neuropathy is found soon after acute exposure. The neuropathy usually develops within 2 to 3 weeks of acute or subacute exposure, although the latent period may be as long as 1 to 2 months. Symptoms may worsen over a few weeks despite lack of further exposure, but they eventually stabilize. With low-dose chronic exposure, the latent period is more difficult to determine. In either circumstance, systemic symptoms are also conspicuous. With chronic exposure, similar but less severe gastrointestinal disturbances develop, as may skin changes such as melanosis, keratoses, and malignancies. Mees lines are white transverse striations of the nails (striate leukonychiae) that appear 3 to 6 weeks after exposure (Fig. 58.1). As a nonspecific manifestation of nail matrix injury, Mees lines can be seen in a number of other conditions including thallium poisoning, chemotherapy, and a variety of systemic disorders.

Lead

Occupational exposure to lead occurs in workers in smelting factories and metal foundries and those involved in demolition, ship breaking, manufacturing of batteries or paint pigments, and construction or repair of storage tanks. Occupational exposure also occurs in the manufacture of ammunition, bearings, pipes, solder, and cables. Nonindustrial sources of lead poisoning are home-distilled whiskey, Asian folk remedies, earthenware pottery, indoor firing ranges, and retained bullets. Lead has been used to artificially increase the weight of illicit marijuana and has then been inhaled with it (Busse et al., 2008). Artifical turf may also pose an exposure threat to unhealthy levels of lead: the lead is released in dust that may be ingested or inhaled, but whether in sufficient amount to cause neurotoxicity is unclear. Lead neuropathy reached epidemic proportions at the end of the 19th century because of uncontrolled occupational exposure but now is rare because of strict industrial regulations. Exposure also may result from ingestion of old lead-containing paint in children with pica and consumption of illicit spirits by adults. Absorption is commonly by ingestion or inhalation but occasionally occurs through the skin.

The toxic effects of inorganic lead salts on the nervous system commonly differ with age, producing acute encephalopathy in children and polyneuropathy in adults. Children typically develop an acute gastrointestinal illness followed by behavioral changes, confusion, drowsiness, reduced alertness, focal or generalized seizures, and (in severe cases) coma with intracranial hypertension. At autopsy, the brain is swollen, with vascular congestion, perivascular exudates, edema of the white matter, and scattered areas of neuronal loss and gliosis. In adults, an encephalopathy is less common, but behavioral and cognitive changes are sometimes noted. In adults, lead produces a predominantly motor neuropathy, sometimes accompanied by gastrointestinal disturbances and a microcytic, hypochromic anemia. The neuropathy is manifest primarily by a bilateral wrist drop sometimes accompanied by bilateral footdrop or by more generalized weakness that may be associated with distal atrophy and fasciculations. Sensory complaints are usually minor and overshadowed by the motor deficit when the neuropathy develops subacutely following relatively brief exposure to high lead concentrations, but they are more conspicuous when the neuropathy develops after many years of exposure (Thomson and Parry, 2006). The tendon reflexes may be diminished or absent. Older reports describe a painless motor neuropathy with few or no sensory abnormalities and distinct patterns of weakness affecting wrist extensors, finger extensors, and intrinsic hand muscles. Preserved reflexes, fasciculations, and profound muscle atrophy may simulate amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. A rare sign of lead exposure is a blue line at the gingival margin in patients with poor oral hygiene. Hypochromic microcytic anemia with basophilic stippling of the red cells, hyperuricemia, and azotemia should stimulate a search for lead exposure. Prognosis for recovery from the neuropathy is good when the neuropathy is predominantly motor and evolves subacutely, but it is less favorable when the neuropathy is motor-sensory in type and more chronic in nature (Thomson and Parry, 2006).

Lead intoxication is confirmed by elevated blood and urine lead levels. Blood levels exceeding 70 µg/100 mL are considered harmful, but even levels greater than 40 µg/100 mL have been correlated with minor nerve conduction abnormalities. Subjects should be removed from further occupational exposure if a single blood lead concentration exceeds 30 µg/100 mL or if two successive blood lead concentrations measured over a 4-week interval equal or exceed 20 µg/100 mL (Kosnett et al., 2007). Lead inhibits erythrocyte δ-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase and other enzymatic steps in the biosynthetic pathway of porphyrins. Consequently, increased red cell protoporphyrin levels emerge together with increased urinary excretion of δ-aminolevulinic acid and coproporphyrin. Excess body lead burden, confirming past exposure, can be documented by increased urinary lead excretion after a provocative chelation challenge with calcium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. Only a few electrophysiological studies have been reported in patients with overt lead neuropathy. These investigations indicate a distal axonopathy affecting both motor and sensory fibers. These observations corroborate changes of axonal degeneration seen in human nerve biopsies. Contrary to the findings in humans, lead produces segmental demyelination in animals. Lead is known to cause early mitochondrial changes in cell culture systems, but the biochemical mechanisms leading to neurotoxicity remain unknown.

Lead encephalopathy is managed supportively, but corticosteroids are given to treat cerebral edema. Chelating agents (dimercaprol or 2,3-dimercaptopropane sulfonate) are also prescribed for patients with symptoms of lead toxicity (Kosnett et al., 2007). No specific treatment exists for lead neuropathy other than prevention of further exposure to lead. Chelation therapy does not hasten recovery.

Manganese

Manganese miners may develop neurotoxicity following inhalation for prolonged periods (months or years) of dust containing manganese. Headache, behavioral changes, and cognitive disturbances (“manganese madness”) are followed by the development of motor symptoms such as dystonia, parkinsonism, retropulsion, and a characteristic gait called cock-walk manifested by walking on the toes with elbows flexed and the spine erect. There is usually no tremor, and the motor deficits rarely improve with l-dopa therapy. MRI may show changes in the globus pallidus, and this may be helpful in distinguishing manganese-induced parkinsonism from classic Parkinson disease (PD). Manganese intoxication has been reported in miners, smelters, welders, and workers involved in the manufacture of dry batteries, after chronic accidental ingestion of potassium permanganate, and from incorrect concentration of manganese in parenteral nutrition. Welders with PD were found to have their onset of PD an average of 17 years earlier than a control population of PD patients, suggesting that welding, possibly by causing manganese toxicity, is a risk factor for PD (Racette et al., 2001). However, a recent nationwide record linkage study from Sweden did not support a relationship between welding and PD or any other movement disorder (Fored et al., 2006). The controversy regarding the relationship between welding and PD has been reviewed by Jankovic (2005). In addition to welding and manganese mining, manganese toxicity may occur with chronic liver disease and long-term parenteral nutrition. Manganese intoxication may be associated with abnormal MRI (abnormal signal hyperintensity in the globus pallidus and substantia nigra on T1-weighted images). In contrast to PD, fluorodopa positron emission tomography (PET) studies are usually normal in patients with manganese-induced parkinsonism, and raclopride (D2 receptor) binding is only slightly reduced in the caudate and normal in the putamen. Neuronal loss occurs in the globus pallidus and substantia nigra pars reticularis, as well as in the subthalamic nucleus and striatum. There is little response to l-dopa of the extrapyramidal syndrome, which may progress over several years. Myoclonic jerking may occur, sometimes without extrapyramidal accompaniments (Ono et al., 2002).

Chelation therapy is of uncertain benefit in patients with manganese toxicity, although claims of improvement in parkinsonism among small series of manganese-exposed subjects have been made (Herrero Hernandez et al., 2006).

Mercury

The toxic effects of elemental mercury (mercury vapor), inorganic salts, and short-chain alkyl-mercury compounds predominantly involve the central nervous system (CNS) and dorsal root ganglion sensory neurons. Inorganic mercury toxicity may result from inhalation during industrial exposure, as in thermometer and battery factories, mercury processing plants, and electronic applications factories. In the past, exposure occurred particularly in the hat-making industry. No evidence exists that the mercury contained in dental amalgam imposes any significant health hazard. Differences in health and cognitive function between dentists and control subjects cannot be attributed directly to mercury (Ritchie et al., 2002). Clinical consequences of exposure include cutaneous erythema, hyperhidrosis, anemia, proteinuria, glycosuria, personality changes, intention tremor (“hatter’s shakes”), and muscle weakness. The personality changes (“mad as a hatter”) consist of irritability, euphoria, anxiety, emotional lability, insomnia, and disturbances of attention with drowsiness, confusion, and ultimately stupor. A variety of other central neurological deficits may occur but are more conspicuous in patients with organic mercury poisoning.

Effects of Ionizing Radiation

Electromagnetic and particulate radiation may lead to cell damage and death. Radiation therapy affects the nervous system by causing damage to cells (particularly their nuclei) in the exposed regions; these cells include neurons, glia, and the blood vessels supplying neural structures. As a late carcinogenic effect, radiation therapy may also produce tumors, particularly sarcomas, that lead to neurological deficits. Neurological injury is proportional to both the total dose and the daily fraction of radiation received. The combination of radiation therapy with chemotherapy may increase the risk of radiation damage. Preclinical studies are investigating whether certain growth factors or metalloporphyrin antioxidants can prevent damage or hasten recovery of neural structures from radiation injury (Pearlstein et al., 2010). Neurological deficits may also arise as a secondary consequence of radiation (e.g., from vertebral osteoradionecrosis), leading to pain or compression of the spinal cord or nerve roots.

Encephalopathy

Radiation encephalopathy is best considered according to its time of onset after exposure (Grimm and DeAngelis, 2008).

Delayed radiation encephalopathy occurs several months or longer after cranial irradiation, particularly when doses exceed 35 Gy. It may be characterized by diffuse cerebral injury (atrophy) or focal neurological deficits. Slowness of executive function may occur, and there may be marked alterations of frontal functions such as in attention, judgment, and insight (Moretti et al., 2005). The disorder may result from focal cerebral necrosis caused by direct radiation damage or vascular changes. Immunological mechanisms also may be involved. Occasionally patients develop a progressive disabling disorder with cognitive and affective disturbances and a disorder of gait approximately 6 to 18 months after whole-brain irradiation. Such a disturbance may occur more commonly in elderly patients after irradiation. Pathological examination in some instances has shown demyelinating lesions.

Myelopathy

A myelopathy may result from irradiation involving the spinal cord. Transient radiation myelopathy usually occurs within the first year or so after incidental spinal cord irradiation in patients treated for lymphoma and neck and thoracic neoplasms. Paresthesias and the Lhermitte phenomenon characterize the syndrome, which is self-limiting and probably relates to demyelination of the posterior columns. A delayed severe radiation myelopathy may occur 1 or more years after completion of radiotherapy, especially with doses exceeding 60 Gy to the spinal cord. Patients present with a focal spinal cord deficit that progresses over weeks or months to paraplegia or quadriplegia. This may simulate a compressive myelopathy or paraneoplastic subacute necrotizing myelopathy, but the changes on MRI are usually those of a focal increased T2-weighted myelomalacia with cord atrophy in the originally irradiated field. The CSF is usually normal, although the protein concentration is sometimes elevated. Corticosteroids may lead to temporary improvement, but no specific treatment exists. The disorder is caused by necrosis and atrophy of the cord, with an associated vasculopathy (Okada and Okeda, 2001). Occasional patients develop sudden back pain and leg weakness several years after irradiation, with MRI revealing hematomyelia; symptoms usually improve with time.

In some instances, inadvertent spinal cord involvement, usually by irradiation directed at the paraaortic nodes in cases of seminoma, leads to a focal lower-limb lower motor neuron syndrome (see Chapter 74). The neurological deficit may progress over several months or years but eventually stabilizes, leaving a flaccid asymmetrical paraparesis. Recovery does not occur.

Plexopathy

A radiation-induced plexopathy may rarely occur soon after radiation treatment for neoplasms, particularly of the breast and pelvis, and must be distinguished from direct neoplastic involvement of the plexus (Dropcho, 2010). Paresthesias, weakness, and atrophy typify the disorder, which tends to plateau after progressing for several months. The plexopathy may develop 1 to 3 years or longer after irradiation that involves the brachial or lumbosacral plexus. In this regard, doses of radiation exceeding 60Gy, use of large daily fractions, involvement of the upper part of the brachial plexus, lymphedema, induration of the supraclavicular fossa, and the presence of myokymic discharges on EMG all favor a radiation-induced plexopathy. Although radiation plexopathy is often painless, a point favoring this diagnosis rather than direct infiltration by neoplasm, pain is conspicuous in some patients. Symptoms progress at a variable rate. The plexopathy is associated with small-vessel damage (endarteritis obliterans) and fibrosis around the nerve trunks.

Effects of Nonionizing Radiation

Concern has been raised that occupational or environmental exposure to high-voltage electric power lines may lead to neurological damage from exposure to high-intensity electromagnetic fields. However, the effects of such exposure are uncertain and require further study. Nonionizing radiation at the radiofrequency used by cellular telephones has been reported to cause sleep disturbances, headache, and other nonspecific neurological symptoms. Several studies have raised concerns that such radiation may cause brain tumors or accelerate their growth, although a clear theoretical basis for such an association with brain tumors is lacking. In any event, the available data fail to show a causal association between the use of cellular telephones and fast-growing tumors such as malignant gliomas. For slow-growing tumors (e.g., meningiomas, acoustic neuromas) and for gliomas among long-term users, the lack of any reported association is less conclusive because the observation period is still so short (Ahlbom et al., 2009). Most safety standards for exposure to radiofrequency radiations relate to the avoidance of harmful heating or electrostimulatory effects. There are case reports of burning sensations or dull aches of the face or head on the side that the telephone is used. Radiofrequency radiations have also been associated with dysesthesias, generally without objective neurophysiological evidence of peripheral nerve damage (Westerman and Hocking, 2004). The basis of such symptoms is unclear.

Electric Current and Lightning

Electrical injuries (whether from manufactured or naturally occurring sources) are common. Their severity depends on the strength and duration of the current and the path in which it flows. Electricity travels along the shortest path to ground. Its passage through humans can often be determined by identifying entry and exit burn wounds. When its path involves the nervous system, direct neurological damage is likely among survivors. With the passage of current through tissues, heat is produced, which is responsible at least in part for any damage, but nonthermal mechanisms may also contribute (Winkelman, 2008). In addition, neurological damage may result from circulatory arrest or trauma related to falling or a shock pressure wave.

When the path of the current involves the spinal cord, a transverse myelopathy may occur immediately or within 7 days or so and may progress for several days. The disorder eventually stabilizes, after which partial or full recovery occurs in many instances (Lakshminarayanan et al., 2009). Upper and lower motor neuron deficits and sensory disturbances are common, but the sphincters are often spared. Unlike traumatic myelopathy, pain is not a feature. Autopsy studies show demyelination of long tracts, loss of anterior horn cells, and areas of necrosis in the spinal cord.

Trauma resulting from the electrical injury (e.g., falls) may lead to intracranial hemorrhage, either subdurally, epidurally, or in the subarachnoid space. Long-term consequences of electrical injuries include neuropsychological symptoms such as fatigue, impaired concentration, irritability and emotional lability, and posttraumatic stress disorder (Ritenour et al, 2008).

Vibration

Exposure to vibrating tools such as pneumatic drills has been associated with both focal peripheral nerve injuries such as carpal tunnel syndrome and vascular abnormalities such as Raynaud phenomenon (Sauni et al., 2009). The mechanism of production is uncertain but presumably reflects focal damage to nerve fibers. The designation of hand-arm vibration syndrome has been applied to a combination of vascular, neurological, and musculoskeletal symptoms and signs that may occur in those using handheld vibrating tools such as drills and jackhammers. There may be blanched, discolored, swollen, or painful fingers; paresthesias or weakness of the fingers; pain and tenderness of the forearm; and loss of manual dexterity (Weir and Lander, 2005). The pathophysiological basis of the syndrome is poorly understood, and treatment involves avoidance of exposure to cold or vibrating tools.

Hyperthermia

Patients have been described who received 915-MHz hyperthermia treatment together with ionizing radiation for superficial cancers and developed nonspecific burning, tingling, and numbness in the territory of an adjacent nerve (Westerman and Hocking, 2004). Once the symptoms developed, they occurred with the application of power without any time lag and ceased as soon as power was removed, suggesting that they were not a thermal effect. Dysesthesias have also been reported after accidental exposures in faulty microwave ovens (Westerman and Hocking, 2004). The precise neurophysiological basis for such symptoms has not been elucidated.

Burns

Peripheral complications of burns are also important. Nerves may be damaged directly by heat, leading to coagulation necrosis from which recovery is unlikely. A compartment syndrome may arise from massive swelling of tissues and mandates urgent decompressive surgery. In other instances, neuropathies result from compression, angulation, or stretching due to incorrectly applied dressings or improper positioning of the patient. A critical illness polyneuropathy and myopathy is now well recognized in patients with multiorgan failure and sepsis, including patients with burns, and is discussed in Chapter 76.

Effects of Drug Abuse

Urine screening for drugs of abuse may be used in the evaluation of patients (Table 58.1). The detection times listed in the table are rough estimates at best, as detection is dependent on the time, dose, and route of administration, the subject’s metabolism, and the specifics of the assay. There are false positives and false negatives. Also, urine testing presently does not detect many drugs such as GHB, MDMA, ketamine, and fentanyl. The urine test provides only qualitative information of recent drug use. Because urinary levels depend on time and clearance, they may not correlate with toxic symptoms. Moreover, most studies suggest that routine urine drug screening in the acute hospital setting has minimal impact on patient care, as most of acute treatment is directed toward supportive care and treatment of specific neurological, cardiovascular, and respiratory dysfunction.

Table 58.1 Common Drugs of Abuse: Approximate Detection Time After Last Drug Use When Drugs or Their Metabolites Are Still Detectable in Urine

| Drug | Detection Time After Last Use |

|---|---|

| Amphetamine | 48 hours |

| Cocaine | 48 hours |

| Benzodiazepines* | 5 to 7 days |

| Barbiturates, long-acting | 7 days |

| Barbiturates, short- or intermediate-acting | 1 to 2 days |

| Heroin* | 4 to 5 days |

| Methadone | 3 days |

| Morphine | 48 hours |

| Phencyclidine* | 2 weeks |

| Propoxyphene | 48 hours |

* Maximum detection times given for chronic users. Single dose in nonhabitual users is cleared more rapidly.

All the substances of abuse have potent acute and chronic effects on the nervous system. For the sake of discussion, it is helpful to divide their neurological consequences into three broad categories according to the main mechanism of action: acute intoxication, withdrawal syndrome in a habitual user, and indirect complications in which the nervous system is secondarily involved through immune, infectious, cardiovascular, or traumatic mechanisms (Box 58.1).

Pharmacological Effects of Drug Abuse

Opioid Analgesics

Opioid Abuse

Aside from the analgesic effects, morphine or heroin acutely produces a sense of “rush” accompanied by either euphoria or dysphoria and hallucinations. Other effects include pruritus, dry mouth, nausea and vomiting, constipation, and urinary retention. Overdose leads to coma, respiratory suppression, hypotension, and hypothermia. Examination of an overdosed patient may show marked pupillary constriction such that it may be difficult to discern the light reflex. Seizures sometimes occur with intoxication from meperidine, propoxyphene, and fentanyl but usually do not occur with heroin overdose (Brust, 2006).

Sedatives and Hypnotics

Benzodiazepines

Initial treatment of comatose patients with benzodiazepine overdose should be directed to management of cardiovascular and respiratory functions. Flumazenil is a specific antagonist for benzodiazepines. It rapidly reverses the stupor or coma, although its usefulness is limited by its short action of only 30 to 60 minutes and by the possibility of precipitating seizures in susceptible individuals (Seger, 2004). It should be used with caution in habitual benzodiazepine users, patients with history of head trauma, and those who may have taken any proconvulsant. If it is to be used, an initial dose of 0.2 mg should be given IV and repeated every 30 seconds up to a total dose of 2 mg or until the symptoms are reversed.

Psychomotor Stimulants

Of the neurological symptoms seen in the emergency department, headache is probably the most common and frequently accompanies other more serious symptoms such as encephalopathy, myoclonus, or seizures. In a survey of patients with first-time seizures of any cause, drug abuse was responsible for about 20% (McFadyen, 2004). Of the abused stimulants, cocaine is the most likely to cause seizures (Zagnoni and Albano, 2002). Seizures are more likely when cocaine is smoked (“crack”) or given IV than with other modes of administration. The estimate of seizure frequency varies widely from approximately 1% to 40%, depending on the study population. Typically, seizures occur within 1 to 2 hours of cocaine use.

Other drugs such as methamphetamine, amphetamine, MDMA, GHB, methylphenidate, ephedrine, and phenylpropanolamine also cause seizures (Brust, 2006). MDMA in particular has been linked to the development of hyponatremia, with resultant seizures and encephalopathy. The mechanism may involve inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (Hartung et al., 2002).

Both acute ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes have been reported in association with stimulant use. This is especially true for cocaine and amphetamine, although other stimulants may also be responsible. Stroke is discussed further in a later section (see Indirect Complications of Drug Abuse). Movement disorders are sometimes seen after stimulant use. Hyperkinetic movement disorders may be exacerbated or may develop de novo in cocaine users. These include vocal and motor tics, chorea, dystonia, and acute dystonic reaction to neuroleptics. Rarely, dyskinesias may persist months after abstinence (Weiner et al., 2001). Oromandibular stereotypical symptoms such as teeth grinding and tongue protrusion are frequent among amphetamine users.

Other Substances of Abuse

3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine

3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, or Ecstasy) merits a special mention, as it has become a very popular club drug, and there is a misconception among users that it is safe. The drug is used commonly in all-night dance parties. It is a derivative of methamphetamine and has properties of both a stimulant and a hallucinogen. The hallucinogenic effects result from its structural resemblance to mescaline. MDMA acutely causes central serotonergic discharge that is the physiological basis for its psychic effects. Although the incidence of serious complications with MDMA use is low, they do occur unpredictably and consist of delirium, seizure, coma, and (rarely) death. Systemic complications may include hyperthermia, hyponatremia, rhabdomyolysis, hepatic failure, coagulopathy, and cardiac arrhythmias. Adding to the unpredictability is the fact that the street name, Ecstasy, has also been applied by vendors and users to other related compounds: 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA), N-ethyl-3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDEA), paramethoxyamphetamine (PMA), and an expanding list of new inadequately tested “designer amphetamines” (Haroz and Greenberg, 2005).

Indirect Complications of Drug Abuse

Stroke

Drug abuse is likely the most important risk factor for stroke in patients younger than 35 to 45 years of age. The possible mechanisms are diverse (Box 58.2) and depend on the route of drug administration and agents involved. Cocaine and amphetamines are the most commonly implicated (Westover et al., 2007). Both ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes are encountered. Evaluation of these patients should include a careful search for endocarditis or other source of embolization, a full cardiac evaluation, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and antiphospholipid antibody assay. Brain computed tomography (CT) or MRI should include vascular imaging protocols. Dedicated angiography may be indicated, particularly when vasculitis, aneurysms, or vascular malformations are suspected.

Vasculitis and Other Vasculopathies

Cocaine

Cocaine accounts for approximately 50% of drug-related stroke. Both cerebral ischemia and cerebral hemorrhage are common modes of presentation. Neurological symptoms typically develop within hours of cocaine use, although rarely symptoms may progress gradually for up to a week. Seizures sometimes accompany strokes. There are reports of transient ischemic attacks or ischemic infarctions of almost any area of the brain or spinal cord. Asymptomatic subcortical white-matter lesions are also more prevalent in cocaine users than in normal controls (Lyoo et al., 2004).

Hypotension and Anoxia

Anoxic brain injury often follows coma from drug overdose, most notably overdose from opiates and sedatives. An autopsy series of heroin addicts found that 2% had ischemic injury to the globus pallidus. A chronic leukoencephalopathy has also been observed in the setting of long-term heroin vapor inhalation (“chasing the dragon”). Patients present with abulia, cognitive dysfunction, gait instability, and upper motor neuron signs. MRI shows diffuse symmetrical abnormal T2 signals in subcortical, cerebellar, and brainstem white matter (Halloran et al., 2005). It is unclear whether this condition is caused by drug-induced anoxia or due to a specific toxic property of the drug.

Toxin-Mediated Disorders

The most common of these Clostridium-related disorders is wound botulism. Since its recognition in 1982 in New York, there has been an alarming rise in its incidence among injection drug users worldwide. It now makes up about one-third of all botulism cases in the United States (Davis and King, 2008). Most cases occur in association with subcutaneous or IM injection of heroin. The condition has also been encountered rarely in sinusitis secondary to intranasal cocaine use. The source of the toxin is Clostridium botulinum that grows in wounds after trauma or injection. The clinical picture of bulbar and descending weakness is similar to that seen in foodborne botulism (see Chapter 53C).

Tetanus is an uncommon disease caused by tetanospasmin produced by Clostridium tetani. About 15% of tetanus cases in the United States occurred in injection drug users (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2003). Tetanospasmin inhibits GABA and glycine and causes uninhibited reflex muscle activities. The muscle spasms may be localized (affecting muscles close to the site of infection), cephalic (involving only the cranial muscles), or generalized (involving both cranial and limb muscles). The disease is described in greater detail elsewhere (see Chapter 53C).

Rhabdomyolysis and Myopathy

Rhabdomyolysis is a frequent observation in patients admitted for drug abuse. Evidence of muscle injury ranges from asymptomatic elevation of serum creatine kinase to severe myoglobinuria and renal failure. It is most common in patients abusing heroin, cocaine, amphetamine, MDMA, and phencyclidine. In a retrospective review of 475 patients with rhabdomyolysis (Melli et al., 2005), 34% was attributable to illicit drug or alcohol use, although the agents were not specified. It is unclear whether any of the commonly abused drugs are directly toxic to muscles. The patients were typically severely intoxicated. Possible mechanisms include trauma, muscle crush injury from lying comatose for many hours, hypotension, hypertension, fever, seizures, and excessive muscular activity.

Neuropathy and Plexopathy

Compressive or stretch injuries to peripheral nerves and plexuses may result from drug abuse of any kind. The most commonly affected sites are the brachial plexus, the radial nerve at the upper arm, ulnar nerve at the elbow, sciatic nerve in the gluteal region, and peroneal nerve at the fibular head. Focal neuropathies may also develop as a result of compartment syndrome and secondary nerve ischemia. Some cases of brachial or lumbosacral plexopathy in the absence of mechanical injury have been linked to heroin use (Dabby et al., 2006). A toxic or hypersensitivity reaction to heroin is possible.

Neurotoxins of Animals and Insects

Snakes

Over 5 million snakebites occur worldwide per year, with half of them venomous, resulting in about 400,000 amputations and up to 125,000 deaths. Only about 6800 cases with fewer than 10 deaths are reported in the United States each year (Langley, 2008). In contrast, cases are commonly encountered in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Mortality and morbidity are particularly associated with impoverished rural communities (Williams et al., 2010).

The majority of venomous snakebites are inflicted by the pit vipers (subfamily Crotalidae), a group that includes rattlesnakes (genera Crotalus and Sistrurus), fer-de-lances (genus Bothrops), and the bushmaster (Lachesis muta). Moccasins (genus Agkistrodon), including cottonmouths and copperheads, account for up to half of pit viper envenomations in the United States. Pit vipers are so named because of an identifiable heat-sensing foramen, or “pit,” between each eye and nostril; they have a triangular head with elliptical pupils and retractable canalized fangs (Gold et al., 2002). Important venomous snakes in other parts of the world include Elapidae such as cobras, mambas, kraits, coral snakes (Maticora species), and most Australian venomous snakes. Viperidae (true vipers) include the puff adder (Bitis arietans), Gaboon viper (Bitis gabonica), rhinoceros-horned viper (Bitis nasicornis, and Russell’s viper (Daboia russelii). Hydrophiidae (pelagic sea snakes) have highly neurotoxic venom but rarely bite humans.

Initial laboratory evaluation should include complete blood cell and platelet counts, coagulation panel, fibrinogen, fibrin split products, serum chemistries, creatine kinase, and urinalysis. In patients with weakness, nerve conduction studies with repetitive stimulation may reveal a pattern of either pre- or postsynaptic blockade. The observed changes consist of reduced amplitude of compound muscle action potentials, decremental response to low-frequency repetitive stimulation, and postexercise and posttetanic facilitation. Treatment includes calming and supportive measures. Even in the absence of life-threatening symptoms, a patient should be monitored for at least 6 hours if bitten by a pit viper and 12 hours if bitten by a coral snake. Appropriate immunoglobulin antivenom may be administered as soon as it is certain that significant envenomation has occurred (Warrell, 2010). In survivors of snake bites, the main source of disability is local tissue necrosis that may lead to disfigurement or limb amputation.

Spiders

Of the commonly encountered spiders, few produce significant symptoms in humans. The female widow spider (Latrodectus sp.) is the most important to the neurologist. Of the approximately 2600 widow bites reported annually in the United States, 13 had major health consequences, and no fatality occurred (Langley, 2008). Black widow spider (Latrodectus mactans mactans) venom contains α-latrotoxin, a potent neurotoxin capable of inducing release and blocking reuptake of neurotransmitter at presynaptic cholinergic, noradrenergic, and aminergic nerve endings. Venom of Phoneutria banana spiders from South America and Atrax funnel web spiders from Australia also cause neurotoxicity. Another clinically important spider, the brown recluse spider (Loxosceles reclusa), is responsible for local tissue damage and systemic symptoms that rarely may include disseminated intravascular coagulation, hemolysis, shock, and multisystem failure.

Scorpions

Although only a few of the approximately 1400 scorpion species are of neurological importance, bites by poisonous scorpions are generally more dangerous than spider bites. Scorpion envenomation is second only to snake bites as a public health problem in the tropics and North Africa. In Mexico alone, 100,000 to 200,000 scorpion bites occur annually, resulting in 400 to 1000 fatalities. In the United States on average, approximately 14,700 scorpion bites with no fatalities are reported annually (Langley, 2008). Small children in particular are prone to developing neurological effects, and as many as 80% of bites are symptomatic. The venoms of the poisonous scorpions contain a wide range of polypeptides that have a net excitatory effect on the nervous system.

Presenting symptoms are highly variable, from local pain (which may be secondary to serotonin found in scorpion stings) to a general state of intoxication. Paresthesias are common and usually experienced around the site of the bite but also may be felt diffusely. Autonomic symptoms of sympathetic excess (tachycardia, hypertension, and hyperthermia) are often present, but parasympathetic symptoms including the SLUD syndrome (salivation, lacrimation, urination, and defecation) may be present as well. Muscle fasciculations, spasms, limb flailing, dysconjugate roving or rotary ocular movements, dysphagia, and other cranial nerve signs are sometimes seen. With severe envenomation, encephalopathy may result from direct CNS toxicity or secondary to uncontrolled hypertension. Symptom control, cardiovascular and respiratory support, and antivenom administration are the mainstays of treatment. Scorpion antivenom appeared to be effective in a small randomized control trial in children with neurotoxicity (Boyer et al., 2009). Generalization of this result is uncertain owing to geographical differences in the venom and in the quality and safety of the antivenom.

Tick Paralysis

Electrodiagnostic findings are likely to be nonspecific during the acute phase of the disease, although only limited data are available. One study reported low-amplitude compound muscle action potentials with normal conduction velocities and sensory nerve conduction studies (Vedanarayanan et al., 2002). There is a case report of unilateral conduction block at the lower trunk of the brachial plexus from a tick bite in the ipsilateral axilla (Krishnan et al., 2009). Repetitive nerve stimulation studies are usually normal. The key to diagnosis is to find the culpable tick by careful inspection of the patient’s skin. The tick can then be removed, leading to rapid and dramatic clinical improvement usually over just a few hours.

Neurotoxins of Plants and Fungi

A comprehensive review of the numerous botanical toxins is impossible. Table 58.2 lists several major categories and the commonly associated plants in each category. Omitted are plants that do not have direct toxicity on the nervous system, such as those containing cardiac glycosides, coumarin, oxalates, taxines, andromedotoxin, colchicine, and phytotoxins. Secondary neurological disturbances may result from these toxins because some can cause electrolyte abnormalities, cardiovascular dysfunction, or coagulopathy.

| Principal Toxins | Plants (Representative Examples) | Main Clinical Features |

|---|---|---|

| Tropane (belladonna) alkaloids | Jimson weed (Datura stramonium); deadly nightshade (belladonna, Atropa belladonna); matrimony vine (Lycium halimifolium); henbane (Hyoscyamus niger); mandrake (Mandragora officinarum); jasmine (Cestrum spp.) | Mydriasis, cycloplegia, tachycardia, dry mouth, hyperpyrexia, delirium, hallucinations, seizures, coma |

| Solanine alkaloids | Woody nightshade (bittersweet, Solanum dulcamara); black nightshade (Solanum nigrum); Jerusalem cherry (Solanum pseudocapsicum); wild tomato (Solanum gracile); leaves and roots of the common potato (Solanum tuberosum) | As above |

| Nicotine-like alkaloids (e.g. cytisine) | Tobacco (Nicotiana spp.); golden chain (Laburnum anagyroides); mescal bean (Sophora spp.); Scotch broom (Cytisus spp.); poison hemlock (Conium maculatum) | Variable sympathetic and parasympathetic hyperactivity, hypotension, drowsiness, weakness, hallucinations, seizures |

| Cicutoxin | Water hemlock (Cicuta maculata) | Diarrhea, abdominal pain, salivation, seizures, coma |

| Triterpene | Chinaberry (Melia azedarach) | Confusion, ataxia, dizziness, stupor, paralysis, seizures |

| Anthracenones | Buckthorn (Karwinskia humboldtiana) | Ascending paralysis; polyneuropathy |

| Excitatory amino acid agonists | Chickling pea and others (Lathyrus spp.); cycad (Cycas rumphii); false sago palm (Cycas circinalis) | Neurodegenerative diseases such as motor neuron degeneration |

Jimson Weed

Jimson weed (Datura stramonium), first grown by early settlers in Jamestown from seeds brought from England, was initially used to treat asthma. It is now found throughout the United States. Intoxication is not uncommon, with the majority occurring among young people who intentionally ingest the plant for its psychic effects (Forrester, 2006). The chief active ingredient is the alkaloid, hyoscyamine, with lesser amounts of atropine and scopolamine. Symptoms of anticholinergic toxicity appear within 30 to 60 minutes after ingestion and often continue for 24 to 48 hours because of delayed gastric motility. The clinical picture can include hyperthermia, delirium, hallucinations, seizures, and coma. Autonomic disturbances such as mydriasis, cycloplegia, tachycardia, dry mouth, and urinary retention are often present. Treatment includes gastrointestinal decontamination with or without the induction of emesis. Supportive measures and symptom relief should be provided, but physostigmine should be reserved for severe or life-threatening intoxications.

Water Hemlock

Water hemlock (Cicuta maculata) is a highly toxic plant found primarily in wet, swampy areas and is sometimes mistakenly ingested as wild parsnips or artichokes. Although related to poison hemlock, its clinical toxidrome is quite different. The principle toxin, the long-chain aliphatic alcohol, cicutoxin, is a highly potent noncompetitive GABA receptor antagonist (Uwai et al., 2000). Symptoms consist of initial gastrointestinal effects (abdominal pain, salivation, and diarrhea) followed by generalized convulsions, obtundation, and coma. Mortality is secondary to refractory status epilepticus; seizures are treated with standard protocols.

Excitatory Amino Acids

Another excitatory amino acid, β-methylamino-l-alanine (BMAA), is found in cycad seeds, a dietary staple of the Chamorro people of Guam. When given in sufficient quantity, BMAA can induce neurotoxicity in primates. An unusually high incidence of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, parkinsonism, and dementia was observed in the Chamorros around the second World War, and it has been postulated that BMAA may play an etiological role (Bradley and Mash, 2009). A causal relationship in humans, however, is difficult to prove.

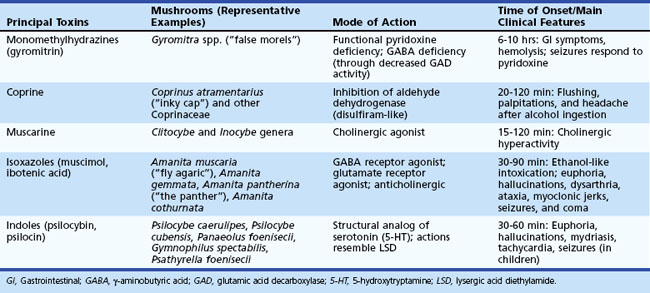

Mushroom Poisoning

Of the more than 5000 varieties of mushrooms, approximately 100 are known to be toxic to humans. Accidental poisoning is common because poisonous mushrooms often closely resemble edible varieties. Aside from accidental ingestion, mushrooms such as Psilocybe spp., Panaeolus, Amanita muscaria, and Amanita pantherina are popular among drug users for their psychoactive effects. Many are used in tribal ceremonies as an intoxicant. Full description of the poisonous mushrooms is beyond the scope of this chapter. The common mushrooms associated with neurological morbidity are listed in Table 58.3.

Marine Neurotoxins

Descriptions of marine food poisoning date back to ancient times. A carving on the tomb of the Egyptian Pharaoh, Ti (ca. 2700 bc), depicts the toxic danger of the puffer fish. Ciguatera intoxication was known during the T’ang Dynasty (618-907 ad) in China. It was later described by early Spanish explorers and in the journals of Captain Cook’s expedition in 1774 (Doherty, 2005). George Vancouver recognized paralytic shellfish poisoning in the Pacific Northwest toward the end of the 18th century.

Ciguatera Fish Poisoning

The ciguatera toxins are produced by algae that thrive in the tropical or subtropical coral reef ecosystem, mainly in the Indo-Pacific and the Caribbean waters between latitudes 35° north and 35° south. The algae are consumed by small herbivorous fish that in turn are eaten by carnivorous ones. As a result, larger and older fish such as barracuda, eel, sea bass, grouper, red snapper, and amberjack are likely to be more toxic, although practically any reef fish eaten in significant quantity can cause ciguatera. Outbreaks can also occur in residents of temperate areas after a return from travel or from consumption of imported fish. The prevalence of ciguatera ranges from 0.1% in residents of large continents to 50% or more in those living in South Pacific and Caribbean islands (Dickey and Plakas, 2010).

Symptoms are typically dose dependent, with more severe poisonings occurring after consumption of the toxin-rich head, liver, and viscera of contaminated fish. Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea first appear within hours of ingestion. Bradycardia and hypotension may accompany the initial acute symptoms. Neurological symptoms then follow (Lewis, 2006). Patients develop centrifugal spread of paresthesias, involving the oral cavity, pharynx, limbs, trunk, and most disagreeably, the genitalia and perineum. Particularly characteristic is a paradoxical temperature reversal. Cold is perceived as burning, tingling, or unbearably hot. Less frequently, warm is perceived as cold. Headache, weakness, fatigue, arthralgia, myalgia, metallic taste, and pruritus are common. Symptoms may be worsened by alcohol consumption, exercise, sexual intercourse, or diets. Some patients are referred to psychiatrists by clinicians unfamiliar with the disease.

Cold allodynia in the distal limbs is a common finding on neurological examination (Schnorf et al., 2002). Some patients have findings of a mild sensory neuropathy. Weakness is generally not present, though rare cases of polymyositis have been reported. A case of transient brain MRI abnormality has been reported (Liang et al., 2009). Most neurological symptoms remit in approximately 1 week, although some degree of paresthesias, asthenia, weakness, and headache may persist for months to years. Lipid storage and slow release of toxin may underlie the prolonged nature of some symptoms.

Gastric lavage may be beneficial if the patient presents soon after ingestion. Intravenous mannitol (20%; 1 g/kg at 500 mL/h) has been used for treatment of acute ciguatera poisoning. The mechanism of action is postulated to be reduction of edema in Schwann cells. The efficacy of mannitol is supported only by uncontrolled case series that report dramatic neurological improvement, especially if mannitol is given soon after symptom onset. One small controlled trial in 50 patients found no difference in outcome between mannitol and saline placebo (Schnorf et al., 2002), although many of the patients were treated over 24 hours after symptom onset. Supportive care during acute disease may include fluid replacement, control of bradycardia, and symptomatic treatment of anxiety, headache, and pain. Calcium gluconate, anticonvulsants, and corticosteroids have been tried with varying results. The chronic symptoms of ciguatera poisoning are difficult to treat. Gabapentin, pregabalin, amitriptyline, or other tricyclic antidepressants may provide partial relief of neuropathic pain.

Puffer Fish Poisoning

Lip, tongue, and distal limb paresthesias appear within minutes to about 2 hours of ingestion. Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain are common. Perioral paresthesias and progressive ascending weakness are apparent in moderately severe cases. Dysphonia, dysphagia, hypoventilation, bradycardia, and hypotension develop in severe intoxications. Coma and seizures may be seen. Fatality rates are high in severely affected individuals and due to respiratory insufficiency, cardiac dysfunction, and hypotension (Chowdhury et al., 2007). Treatment is supportive. Gastric lavage and charcoal are indicated if presentation is early. Neostigmine has been used with anecdotal success. Patients who survive the acute period of intoxication (approximately the first 24 hours) often recover without neurological sequelae.

Liquid chromatography also can detect TTX in serum or urine. Electrophysiological studies may test nerve excitability and show characteristic elevation in threshold and slow conduction in TTX poisoning (Kiernan et al., 2005).

Shellfish Poisoning

Three neurological syndromes result from consumption of shellfish contaminated by toxins: paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP), neurotoxic shellfish poisoning (NSP), and amnestic shellfish poisoning (ASP) (James et al., 2010). All of them are primarily associated with ingestion of bivalve mollusks (clams, mussels, scallops, oysters), filter feeders that can accumulate toxic microalgae. Rarely, poisoning is seen after consumption of other seafood such as predator crabs that may have eaten contaminated shellfish. Outbreaks are more frequent during the summer months, especially during periods of red tides, but they may occur in any month and in the absence of red tides. Shellfish may remain toxic for several weeks after the bloom subsides.

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Toxicological Profile for Styrene. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. Available at http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/ToxProfiles/tp53.pdf, 2007.

Ahlbom A., Feychting M., Green A., et al. Epidemiologic evidence on mobile phones and tumor risk: a review. Epidemiology. 2009;20:639-652.

Boyer L.V., Theodorou A.A., Berg R.A., et al. Antivenom for critically ill children with neurotoxicity from scorpion stings. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2090-2098.

Bradberry S.M., Cage S.A., Proudfoot A.T., et al. Poisoning due to pyrethroids. Toxicol Rev. 2005;24:93-106.

Bradley W.G., Mash D.C. Beyond Guam: the cyanobacteria/BMAA hypothesis of the cause of ALS and other neurodegenerative diseases. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2009;10(Suppl 2):7-20.

Brust J.C. Seizures and substance abuse: treatment considerations. Neurology. 2006;67(12 Suppl 4):S45-S48.

Buckley N.A., Isbister G.K., Stokes B., et al. Hyperbaric oxygen for carbon monoxide poisoning: a systematic review and critical analysis of the evidence. Toxicol Rev. 2005;24:75-92.

Busse F., Omidi L., Timper K., et al. Lead poisoning due to adulterated marijuana. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1641-1642.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tetanus surveillance, United States, 1998-2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:1-8.

Chowdhury F.R., Nazmul Ahasan H.A., Mamunur Rashid A.K., et al. Tetrodotoxin poisoning: a clinical analysis, role of neostigmine and short-term outcome of 53 cases. Singapore Med J. 2007;48:830-833.

Costa L.G., Cole T.B., Vitalone A., et al. Measurement of paraoxonase (PON1) status as a potential biomarker of susceptibility to organophosphate toxicity. Clin Chim Acta. 2005;352:37-47.

Dabby R., Djaldetti R., Gilad R., et al. Acute heroin-related neuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2006;11:304-309.

Davis L.E., King M.K. Wound botulism from heroin skin popping. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2008;8:462-468.

Dickey R.W., Plakas S.M. Ciguatera: a public health perspective. Toxicon. 2010;56:123-136.

Doherty M.J. Captain Cook on poison fish. Neurology. 2005;65:1788-1791.

Dropcho E.J. Neurotoxicity of radiation therapy. Neurol Clin. 2010;28:217-234.

Filley C.M., Halliday W., Kleinschmidt-DeMasters B.K. The effects of toluene on the central nervous system. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63:1-12.

Fored C.M., Fryzek J.P., Brandt L., et al. Parkinson’s disease and other basal ganglia or movement disorders in a large nationwide cohort of Swedish welders. Occup Environ Med. 2006;63:135-140.

Forrester M.B. Jimsonweed (Datura stramonium) exposures in Texas, 1998-2004. J Toxicol Environ Health. 2006;69:1757-1762.

Gash D.M., Rutland K., Hudson N.L., et al. Trichloroethylene: parkinsonism and complex 1 mitochondrial neurotoxicity. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:184-192.

Gold B.S., Dart R.C., Barish R.A. Bites of venomous snakes. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:347-356.

Gold B.G., Voda J., Yu X., et al. The immunosuppressant FK506 elicits a neuronal heat shock response and protects against acrylamide neuropathy. Exp Neurol. 2004;187:160-170.

Grimm S.A., De Angelis L.M. Neurological complications of chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Aminoff M.J., editor. Neurology and General Medicine, fourth ed, New York: Churchill Livingstone, 2008.

Guadarrama-Naveda M., de Cabrere L.C., Matos-Bastidas S. Intermediate syndrome secondary to ingestion of chlorpiriphos. Vet Hum Toxicol. 2001;43:34.

Halloran O., Ifthikharuddin S., Samkoff L. Leukoencephalopathy from “chasing the dragon.”. Neurology. 2005;64:1755.

Hampson N.B., Hampson L.A. Characteristics of headache associated with acute carbon monoxide poisoning. Headache. 2002;42:220-223.

Haroz R., Greenberg M.I. Emerging drugs of abuse. Med Clin North Am. 2005;89:1259-1276.

Hartung T.K., Schofield E., Short A.I., et al. Hyponatraemic states following 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, “ecstasy”) ingestion. Q J Med. 2002;95:431-437.

Herrero Hernandez E., Discalzi G., Valentini C., et al. Follow-up of patients affected by manganese-induced parkinsonism after treatment with CaNa2EDTA. Neurotoxicology. 2006;27:333-339.

Horstman S.W., Browning S.R., Szeluga R., et al. Solvent exposure in screen printing shops. J Environ Sci Health Part A Tox Hazard Subst Environ Eng. 2001;36:1957-1973.

Huang C.C. Carbon disulfide neurotoxicity: Taiwan experience. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 2004;13:3-9.

James K.J., Carey B., O’Halloran J., et al. Shellfish toxicity: human health implications of marine algal toxins. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:927-940.

Jankovic J. Searching for a relationship between manganese and welding and Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2005;64:2021-2028.

Kiernan M.C., Isbister G.K., Lin C.S., et al. Acute tetrodotoxin-induced neurotoxicity after ingestion of puffer fish. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:339-348.

Kosnett M.J., Wedeen R.P., Rothenberg S.J., et al. Recommendations for medical management of adult lead exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:463-471.

Krishnan A.V., Lin C.S., Reddel S.W., et al. Conduction block and impaired axonal function in tick paralysis. Muscle Nerve. 2009;40:358-362.

Lakshminarayanan S., Chokroverty S., Eshkar N., et al. The spinal cord in lightning injury: a report of two cases. J Neurol Sci. 2009;276:199-201.

Langley R.L. Animal bites and stings reported by United States poison control centers, 2001-2005. Wilderness Environ Med. 2008;19:7-14.

Lewis R.J. Ciguatera: Australian perspectives on a global problem. Toxicon. 2006;48:799-809.

Liang C.K., Lo Y.K., Li J.Y., et al. Reversible corpus callosum lesion in ciguatera poisoning. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:587-588.

LoPachin R.M. Acrylamide neurotoxicity: neurological, morphological and molecular endpoints in animal models. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2005;561:21-37.

Lotti M. Low-level exposures to organophosphorus esters and peripheral nerve function. Muscle Nerve. 2002;25:492-504.

Lotti M., Moretto A. Organophosphate-induced delayed polyneuropathy. Toxicol Rev. 2005;24:37-49.

Lyoo I.K., Streeter C.C., Ahn K.H., et al. White matter hyperintensities in subjects with cocaine and opiate dependence and healthy comparison subjects. Psychiatry Res. 2004;131:135-145.

McFadyen M.B. First seizures, the epilepsies and other paroxysmal disorders prospective audit of a first seizure clinic. Scott Med J. 2004;49:126-130.

Melli G., Chaudhry V., Cornblath D.R. Rhabdomyolysis: an evaluation of 475 hospitalized patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2005;84:377-385.

Moretti R., Torre P., Antonello R.M., et al. Neuropsychological evaluation of late-onset post-radiotherapy encephalopathy: a comparison with vascular dementia. J Neurol Sci. 2005;229-230:195-200.

Okada S., Okeda R. Pathology of radiation myelopathy. Neuropathology. 2001;21:247-265.

Ono K., Komai K., Yamada M. Myoclonic involuntary movement associated with chronic manganese poisoning. J Neurol Sci. 2002;199:93-96.

Pastore C., Izura V., Marhuenda D., et al. Partial conduction blocks in n-hexane neuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2002;26:132-135.

Pearlstein R.D., Higuchi Y., Moldovan M., et al. Metalloporphyrin antioxidants ameliorate normal tissue radiation damage in rat brain. Int J Radiat Biol. 2010;86:145-163.

Pilkington A., Buchanan D., Jamal G.A., et al. An epidemiological study of the relations between exposure to organophosphate pesticides and indices of chronic peripheral neuropathy and neuropsychological abnormalities in sheep farmers and dippers. Occup Environ Med. 2001;58:702-710.

Proudfoot A.T. Poisoning due to pyrethrins. Toxicol Rev. 2005;24:107-113.

Racette B.A., McGee-Minnich L., Moerlein S.M., et al. Welding-related parkinsonism. Clinical features, treatment, and pathophysiology. Neurology. 2001;56:8-13.

Ritenour A.E., Morton M.J., McManus J.G., et al. Lightning injury: a review. Burns. 2008;34:585-594.

Ritchie K.A., Gilmour W.H., Macdonald E.B., et al. Health and neurological functioning of dentists exposed to mercury. Occup Environ Med. 2002;59:287-293.

Sanders R.W., Katz K.D., Suyama J., et al. Seizure during hyperbaric oxygen therapy for carbon monoxide toxicity: a case series and five-year experience. J Emerg Med. 2009. 2009 Apr 14. [Epub ahead of print]

Sauni R., Pääkkönen R., Virtema P., et al. Dose-response relationship between exposure to hand-arm vibration and health effects among metalworkers. Ann Occup Hyg. 2009;53:55-62.

Schnorf H., Taurarii M., Cundy T. Ciguatera fish poisoning: a double-blind randomized trial of mannitol therapy. Neurology. 2002;58:873-880.

Seger D. Flumazenil—treatment or toxin. J Tox Clin Toxicol. 2004;42:209-216.

Spencer P.S., Kim M.S., Sabri M.I. Aromatic as well as aliphatic hydrocarbon solvent axonopathy. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2002;205:131-136.

Stone J.D., Peterson A.P., Eyer J., et al. Neurofilaments are nonessential to the pathogenesis of toxicant-induced axonal degeneration. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2278-2287.

Thomson R.M., Parry G.J. Neuropathies associated with excessive exposure to lead. Muscle Nerve. 2006;33:732-741.

Uwai K., Ohashi K., Takaya Y., et al. Exploring the structural basis of neurotoxicity in C(17)-polyacetylenes isolated from water hemlock. J Medi Chem. 2000;43:4508-4515.

Vahidnia A., van der Voet G.B., de Wolff F.A. Arsenic neurotoxicity–a review. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2007;26:823-832.

Vedanarayanan V., Evans O.B., Subramony S.H. Tick paralysis in children. Electrophysiology and possibility of misdiagnosis. Neurology. 2002;59:1088-1090.

Warrell D.A. Snake bite. Lancet. 2010;375:77-88.

Weiner W.J., Rabinstein A., Levin B., et al. Cocaine-induced persistent dyskinesia. Neurology. 2001;56:964-965.

Weir E., Lander L. Hand-arm vibration syndrome. CMAJ. 2005;172:1001-1002.

Westerman R., Hocking B. Diseases of modern living: neurological changes associated with mobile phones and radiofrequency radiation in humans. Neurosci Lett. 2004;361:13-16.

Westover A.N., McBride S., Haley R.W. Stroke in young adults who abuse amphetamines or cocaine: a population-based study of hospitalized patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:495-502.

Williams D., Gutierrez J.M., Harrison R., et al. The Global Snake Bite Initiative: an antidote for snake bite. Lancet. 2010;375:89-91.

Winkelman M.D. Neurological complications of thermal and electrical burns. Aminoff M.J., editor. Neurology and General Medicine, fourth ed, New York: Churchill Livingstone, 2008.

Yamano Y., Kagawa J., Ishizu S., et al. Three cases of acute methyl bromide poisoning in a seedling farm family. Ind Health. 2001;39:353-358.

Zagnoni P.G., Albano C. Psychostimulants and epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2002;43(Suppl 2):28-31.