Chapter 54 Effective Dissemination of Critical Airway Information

The MedicAlert Foundation* National Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry

II. Difficult Airway/Intubation: A Multifaceted Problem

III. Difficult Airway/Intubation: Documentation of Critical Information

IV. Difficult Airway/Intubation: Dissemination of Critical Information

VI. The MedicAlert Foundation National Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry

I Overview

This chapter focuses on how critical airway information can be effectively disseminated to future care providers through the MedicAlert Foundation and the National Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry. The components and benefits of the MedicAlert Foundation and this Registry are compared with those of in-house anesthesia documentation, letters to the patient, airway registries, commercially available for-profit medical alert information systems, and the yet-to-be realized universal EHR. Information on how patients can join the MedicAlert Foundation and enroll in the National Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry can be found in Appendix A.

II Difficult Airway/Intubation: a Multifaceted Problem

A Identification of Patients

Controversies regarding predictors and definitions of “difficult” cases exist both within and among medical specialties that deal with difficult airway/intubation. This is a consequence of the complex interactions among patient variables, the clinical setting, and the skills of the practitioner.21 Historically, the anesthesiology literature has cited an incidence of 1% to 3% unanticipated difficult airway/intubation in patients undergoing general endotracheal anesthesia in the operating room.2–5 More recently, incidences up to 18% have been reported.6,7 In non–operating room emergent intubations, the reported incidence of difficult intubation has ranged from 6% to 10%.8,9

At a local level, if a 1% to 3% incidence is applied, then an institution in which 25,000 general endotracheal anesthetic procedures are performed annually could have 250 to 750 unanticipated difficult airway/intubations per year. On a national level, based on an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) membership of 44,000 and assuming that a full-time practicing anesthesiologist is likely to encounter at least one unanticipated difficult intubation per year,10 there could be 44,000 unanticipated difficult airway/intubations annually in the United States. These numbers do not take into account intubations that occur in clinical settings other than the operating room or are performed by anesthesia care providers who are not members of the ASA. Consideration of the possible number of unanticipated difficult airway/intubations on an international level further shows that the scope of this problem and its impact on patients and the health care system warrants vigorous efforts to identify solutions.

B Multidisciplinary Practice Guidelines and Difficult Airway/Intubation Algorithms

The ASA first developed and published practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway in 1993.2 These guidelines heightened practitioners’ awareness of the scope and magnitude of problems related to complex airway management and encouraged familiarity with a standardized clinical airway algorithm. At that same time, the Johns Hopkins Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Medicine initiated a collaborative effort with the Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery to develop and modify airway management techniques and clinical algorithms.11

More recently, other organizations and countries have proposed and tested their own strategies and algorithms for managing difficult airway/intubation cases.12–15 Some algorithms incorporate the use of new airway devices,16 whereas others are designed for use in settings other than the operating room.8,17 A text on emergency department airway management has recommended a universal algorithm in addition to algorithms for specific circumstances.18,19 Guidelines developed for anesthesiologists in the operating room cannot reasonably be applied to emergent intubation in the field, and the most successful algorithms have been developed at a local level by a multidisciplinary team.20

The creation of these various algorithms is still in harmony with the purpose of the ASA practice guidelines: (1) the practice guidelines are not intended as standards or absolute requirements; (2) they are subject to revision as warranted by the evolution of medical knowledge, technology, and practice; and (3) their recommendations may be adopted, modified, or rejected according to clinical needs and constraints.1 Considering all of these variables tends to move airway management farther away from one standardized difficult airway/intubation algorithm. This leads to the inevitable conclusion, as noted in an ASA editorial, that optimal or preferred tracheal intubation techniques and devices will be different for each individual patient and depend on the skill and experience of the practitioner in that particular clinical setting.21

C A Difficult Airway/Intubation Team

Strategies for improving the response to difficult airway/intubation during an emergency code situation can include the use of a difficult airway response team (DART) and a DART equipment cart such as the one developed in 2008 at the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions. This multidepartmental educational and operational program involved anesthesiology, otolaryngology, trauma surgery, and the emergency department; clarified unclear roles of the various providers; and initiated facility-wide quality improvement of problems such as difficulty accessing specific equipment.22 A retrospective review at this institution of cases from 1992 through 2006 demonstrated an annual frequency of approximately 6.5 emergency surgical airways (cricothyrotomy or tracheostomy). Two years after initiation of a comprehensive DART program, the annual frequency was approximately 2.2, despite an increase in the number of patients reported to have difficult airway/intubation.23 Implementation of the DART program also reduced the number of airway sentinel events from several in the preceding 2 years to none in the first 2 years of the DART program. In addition, no claims related to airway events were paid during this time.24

D Consequences of Difficult Airway Management

The consequences of a difficult airway or difficult intubation can include minor or major adverse medical events or death, professional liability to the practitioner, and direct and indirect costs to the patient and the health care system. In 1988, the ASA Committee on Professional Liability closed claims study found that respiratory events were the most common cause of brain damage and death during anesthesia, with difficult intubation being the likeliest category for risk reduction. The median payment for respiratory claims was $200,000.25 In a 1992 loss analysis study conducted by the Physicians Insurers Association of America, files from 43 physician-owned malpractice insurance companies (representing approximately 2000 anesthesiologists nationally) ranked “intubation problems” as the third most prevalent misadventure. The average paid indemnity for 175 of 339 files was $196,958.26 In an analysis of approximately 5000 claims filed in Maryland over a 15-year period that named an anesthesiologist as a defendant, insertion of an endotracheal tube was the sixth most common medical procedure leading to a liability claim. One malpractice claim was filed for every 7.5 patient injuries that occurred from difficult airway events and adverse outcomes, and a single claim in 1994 resulted in a jury award of $5 million (Laura Morlick, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, MD, personal communication, July 17, 1994). A study of the ASA closed claims database from 1985 to 1999 revealed that 67% of claims of difficult airway liability were associated with intubation.27

During airway management, repeated intubation attempts cause swelling and bleeding, with each attempt creating a greater likelihood of failed intubation and ventilation leading to potentially disastrous consequences, even brain damage or death.18,27,28 Prolongation of the airway management process has been shown to increase the rate complications up to 70% with multiple tracheal intubation attempts.8,29

Most complaints initiated against physicians are unrelated to the physician’s technical skill but arise because of inadequate records or poor communication. More complete documentation and communication may be the practitioner’s best defense.30 A 1994 survey of patients who were enrolled by Johns Hopkins in the MedicAlert National Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry found that, despite experiencing adverse outcomes (cancellation of surgery, dental trauma, soft tissue trauma, desaturation, cardiovascular compromise, and cricothyrotomy or tracheostomy), 100% felt that the enrollment gave them a sense of comfort in that future care providers would understand the significance of their difficult airway/intubation. Enrollment in the Registry and documentation of enrollment in the patient’s medical record is a positive reflection of the provider’s concern for the patient’s future safety.31 In a fall 2010 survey conducted by the MedicAlert Foundation of more than 700 members already enrolled in the National Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry, 69.6% of respondents said that a physician had recommended that they enroll, and 92.7% said that what they expected to gain from enrolling was peace of mind knowing that their difficult airway/intubation information would be available in an emergency (A. Wigglesworth, personal communication, September 23, 2010).

III Difficult Airway/Intubation: Documentation of Critical Information

A Documentation in Medical Records

In 1987, Martin L. Norton and colleagues at the University of Michigan pioneered efforts to more fully evaluate patients with complex airway problems by establishing the University of Michigan Airway Clinic. This is believed to be the first formally established clinic specifically for patients with difficult airway/intubation. Clinical documentation consisted of a handwritten airway clinic record sheet and photodocumentation.32 Since that time, the standard of care for documentation of difficult airway/intubation information has been steadily evolving. In 1992, Lynette Mark and colleagues in the Johns Hopkins Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine Department developed the Anesthesiology Consultant Report. This two-page report fully described the preoperative evaluation of a difficult airway/intubation, including intraoperative airway techniques and management and a narrative description of the events. The Anesthesiology Consultant Report raised the standard of documentation during a patient’s initial episode of care in that its detailed airway management documentation was a more accessible part of the patient’s medical record. Care providers were also alerted by a highly visible wristband.11

In 1993 and 2003, the ASA practice guidelines recommended that anesthesiologists document more fully in the medical record and include a description of the nature of the airway difficulties, the various airway management techniques that were employed, and the extent to which each of these techniques was beneficial or detrimental in managing the difficult airway.1,2

B Documentation in In-House Electronic Medical Records

At the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, the 1992 Anesthesia Consultant Report evolved into an Anesthesia Consult form that contained a template and free-text entry as part of the in-house Johns Hopkins computerized medical record. In 1995, at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, patients’ difficult airway/intubation information was entered into the nurse’s assessment section, and a “difficult airway/intubation” notice was placed in the computerized patient record.33

At present, the electronic medical record (EMR) is, by definition, limited to a single health system. The University of Michigan Department of Anesthesiology and many other facilities use a perioperative clinical information software system such as Centricity (General Electric Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) to collect difficult airway/intubation information in an airway management record that contains required fields, a drop-down menu, and a comment section for free text. This information is available at bedside workstations throughout the facility, including the floor and intensive care units, as part of the EMR.9 Other institutions have developed their own EMR systems for in-house use, with multiple terminals that allow access throughout the hospital.

IV Difficult Airway/Intubation: Dissemination of Critical Information

A ASA Recommendations for Dissemination of Information

Before the creation of the ASA practice guidelines, there was little or no literature discussing the benefits of patient notification of difficult airway management.7 The 1993 ASA practice guidelines recommended that the anesthesiologist inform the patient (or responsible person) of the airway difficulty that was encountered and that notification systems, such as a written report or letter to the patient or communication with the patient’s surgeon or primary caregiver, could be considered.2 The 2003 ASA practice guidelines added a recommendation for a bracelet or equivalent identification device that could be kept with the patient at all times.1

C Verbal Dissemination of Information

Most anesthesiologists inform the patient of a difficult airway/intubation in the postanesthesia care unit. However, this verbal communication of difficult airway information to the patient is unreliable. Communication can be hindered by the patient’s intubation or by postoperative pain or sedation. Family members present are usually more concerned about the patient’s surgical findings and recovery from anesthesia and surgery.7 One study found that 50% of patients informed verbally did not recall or were unsure about ever having had a postoperative conversation with their anesthesiologist.34

D Dissemination of Information via Letters

Beginning in 1992, the Johns Hopkins Anesthesia Consultant Report (described previously) was distributed by letter to the patient’s surgeon and referring physician.11 In 2000, the Department of Anesthesiology at Mayo Clinic Scottsdale began providing written notification to patients about their difficult airway in the form of letters mailed 1 week postoperatively. However, in a follow-up survey 2 years later, 20% of patients could not recall receiving the letter. To improve communication, the Clinic followed up with a telephone call to confirm receipt of the letter and to emphasize the importance of the difficult airway/intubation. A MedicAlert Foundation brochure was also included in the letter. The survey found that of those patients who remembered receiving a difficult airway/intubation letter, 41% had informed their primary care physician of their difficult airway, and 95% who subsequently had surgery had informed their surgeons or anesthesiologist or both. The survey concluded that the patients were able to inform subsequent care providers that they had a difficult airway even though most of them did not understand how “difficult airway” affected their subsequent anesthesia and airway management.34

More recently, various publications have reiterated the need for some type of standard written notification or airway alert form to be distributed to the patient, the primary care provider, and the surgeon.7,35

E Dissemination of Information via Difficult Airway/Intubation Registries

In 1987, the Norton and colleagues at the University of Michigan established a permanent in-house Airway Clinic (described previously) linked to an Airway Registry and an information response center for dissemination of critical airway information. As the Registry grew in size, it became increasingly apparent that the response center could not accommodate 24-hour emergency requests for difficult airway/intubation information, so Registry patients were enrolled in the MedicAlert Foundation registry.36 In 1992, Mark and colleagues at the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions established a permanent in-house Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry.11 This registry still exists, and all patients who are identified as having difficult airway/intubation are entered into this in-house database; a note or flag is placed in their electronic record, and they receive a follow-up letter that includes a brochure and recommendation that they enroll in the MedicAlert Foundation. In 1995, in response to the ASA Difficult Airway Task Force practice guidelines and the Anesthesia Advisory Counsel of the MedicAlert Foundation, an in-house computerized Difficult Airway Registry was initiated at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.36

The purpose of an in-house registry is to disseminate critical airway information during subsequent episodes of care at that facility. A review of 119 patients in the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center difficult airway registry from 1995 to 1997 found that 31 (26%) had returned for surgery one or more times and that the registry provided valuable information for subsequent airway management.37 However, in-house difficult airway/intubation registries are not common, even at tertiary-level institutions, and the information they contain is available only within that institution.

F Dissemination of Information via Electronic Medical Records and Electronic Health Records Systems

More recently, there has been a push to implement an EHR system in American health care, with an increase in motivation provided by funding from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) directed at supporting such implementation. In an EHR system, the patient’s complete health record would be captured across all health care institutions. This is the focus of the ARRA funding, as reinforced by Meaningful Use requirements (explicit criteria for receiving Medicare payments for provision of medical care). In 2011, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center became the first hospital to have its in-house–developed EHR system certified as meeting Meaningful Use requirements.38 Part of the certification involved having the capacity to provide patients with an electronic copy of their health information within 3 business days (if they request it). The goal is to provide patients access to information that is important to them, when they need it, and to allow patients to be treated holistically through coordination with other providers.39 However, an electronic copy of the record provided 3 business days after discharge may not provide access to critical information when patients need it and does not automatically ensure coordination of care with other providers.

A survey found that only 1 in 7 consumers could access their medical records electronically; even when access was possible, 40% were unable to see certain documents (e.g., laboratory reports, prescription history, immunization records).40 In 2009, the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act was passed in an effort to improve the health of Americans and the performance of the health care system. Some of its programs included support for state initiatives for health information exchange and creation of a common platform for health information exchange across the country: the National Health Information Network (NHIN).41

One state program is the Chesapeake Regional Information System for Our Patients (CRISP) in Maryland. Its goal is to deliver the right health information to the right place at the right time. However, not all Maryland hospitals are included in the CRISP program, and the program does not access medical information on a national level, does not provide emergency information to Maryland residents who travel outside of the state or internationally, and does not cover new residents who have moved into the state and whose medical information is housed elsewhere.42 Over time, it is hoped that this and other state programs can be expanded to form the envisioned (NHIN). The emergence and encouraged development of an EHR system in the United States cannot, at present, provide an answer to the need for immediate national or international access to emergency medical information. However, a solution that is already in place and fully operational can be found with the MedicAlert Foundation.

V the Medicalert Foundation

B Services Provided by the MedicAlert Foundation

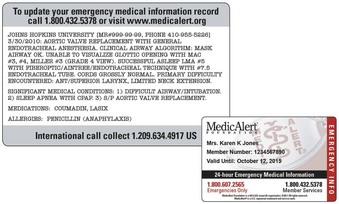

The MedicAlert Foundation’s core services comprise a four-part system: a personalized and custom-made MedicAlert medical ID worn as a bracelet or necklace (Fig. 54-1), a personalized MedicAlert wallet card (Fig. 54-2), an Emergency Medical Information Record (EMIR), and the MedicAlert live 24/7 Emergency Response Service Center. The MedicAlert medical ID and MedicAlert wallet card immediately alert a care provider that the patient has a specific medical condition, such as an allergy, autism, asthma, diabetes, or difficult airway/intubation. Engraved on the medical ID and printed on the wallet card is the toll-free emergency phone number, 1-800-607-2565. For members who travel internationally, MedicAlert recommends that they also have engraved on the medical ID and printed on the wallet card the International Call Collect number, 209-634-4917. The Emergency Response Center accepts all international collect calls and is staffed by a team of medically trained personnel who respond to calls 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, in more than 140 languages.

The MedicAlert Foundation has always been on the cutting edge of information-providing services. In the 1970s, it computerized all of its members’ records and was the first registry to use a scan form system to reduce the costs of data entry.43 Since 1990, the MedicAlert Foundation has offered members their own personal EMIR). Looking to the future, the EHR system envisions seamless, immediate, and simultaneous access by more than one health care provider to all parts of a patient’s record regardless of where those parts were created or stored. Far from competing with the envisioned EHR system, the MedicAlert Foundation has anticipated it and embraced the goal of enabling the dissemination of information to any EHR system. This could be as simple as an HL7 text message or as complicated as a set of discrete data detailing specific medical information. By serving as a central repository in a web of interconnected EHR systems, the MedicAlert Foundation could play a key role in providing critical life-saving information to the clinical systems directly involved in a patient’s care. Finally, as patients continue to become more engaged in managing their own health care through the use of personal health records (PHRs)—as provided by Microsoft, Google, and other vendors—the MedicAlert Foundation will be able to keep patients’ PHRs updated with the latest medical information.

C Membership in the MedicAlert Foundation

MedicAlert Foundation membership is $35/year for adults. This allows members to manage their own personal EMIR, with no limit on the number of updates per year. Members can update their information 24 hours a day by logging on to their own personal secure online account. An annual membership for children is $20/year. A MedicAlert Gold membership is available for $9.95/month; members with this status can consolidate all of their paper records (e.g., laboratory reports, immunization records, radiology reports, electrocardiography results) in an electronic format. Members each have a unique Document Center that can receive faxed medical records from their physicians. The faxed documents are then converted into a PDF file and are available 24 hours a day from any Internet-connected computer. Information on how patients can enroll in the MedicAlert Foundation is presented in Appendix A.

VI the Medicalert Foundation National Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry

A History of the Registry

In 1992, the ASA and others recommended the creation of a national difficult airway registry for the United States.1 At that time, the Anesthesia Advisory Council, a volunteer, multidisciplinary team of anesthesiologists, otolaryngologists, and experts in quality assurance and risk management (see Appendix B), joined together to address the following questions: (1) When an airway event happens, is there consistency in documentation? and (2) Is there a central, accessible database for dissemination of critical airway information? The Council identified only two existing airway databases, those at the University of Michigan Airway Clinic and the MedicAlert Foundation. The Anesthesia Advisory Council recommended the creation of the National Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry within the MedicAlert Foundation to facilitate uniform documentation and effective dissemination of standardized critical information related to complex airway management. The Council selected the category “difficult airway/intubation” as a standard nomenclature to be engraved on the MedicAlert medical ID.

In 1995, the SAM was founded, and the Anesthesia Advisory Council passed the torch to the SAM to take the MedicAlert National Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry into the next millennium.44 Today, it is the only difficult airway/intubation registry that exists at a national level in the United States.

On an international level, Austria established the Austrian Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry (ADAIR) in 1999,45 and Denmark established the Danish Difficult Airway Registry in 2005.46 These registries are not international in scope. Only the MedicAlert Foundation National Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry is truly international, because it is able to disseminate critical information to care providers anywhere in the world 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, in 140 different languages.

C Components of the Registry

The components of the National Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry include information for health care providers and patients, a specialized enrollment form, a secure database, the supporting services of the MedicAlert Foundation (i.e., medical ID, wallet card, EMIR, and 24/7 Emergency Response Service Center), and a follow-up letter sent to the primary care physician or specialist (as indicated by the patient on the enrollment form). In 2003, the ASA practice guidelines recommended that a notification bracelet or equivalent identification device be included as part of a notification system for difficult airway/intubation patients.1 This has always been a part of the MedicAlert system since its beginning in 1956.

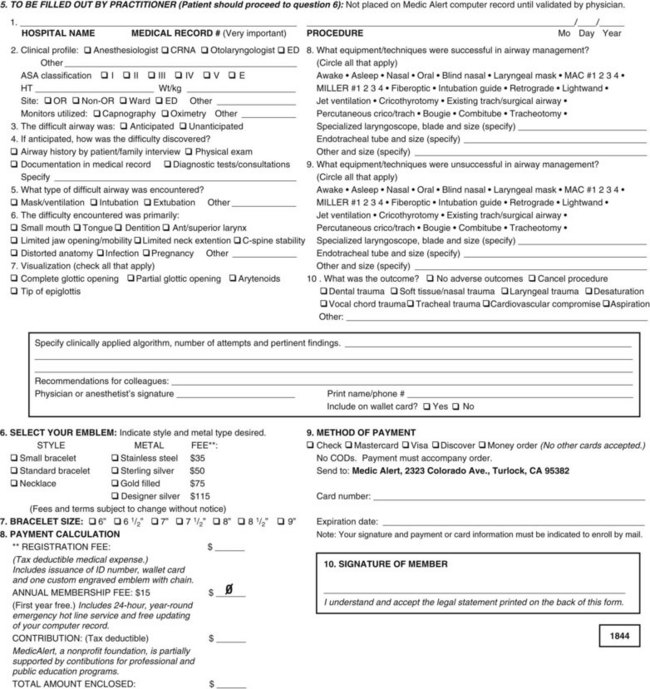

The National Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry specialized enrollment form is in a PDF format. The anesthesiologist downloads the form from the website (www.medicalert.org [accessed April 2012]) and prints it out, or the MedicAlert Foundation can send it to the anesthesiologist as a PDF attachment to an e-mail. The anesthesiologist completes and signs the airway database section (Fig. 54-3) of the enrollment form. This section includes the hospital name, patient’s medical record number, surgical procedure, date of procedure, clinical anesthesia profile, nature of difficulty encountered, reasons for difficulty, successful and unsuccessful techniques, best visualization of airway anatomy, clinically applied algorithm, and clinical outcome. With the exception of specific airway requirements (related to tracheal surgery, stenosis, or other conditions requiring specific sizes of endotracheal tubes), recommendations for future airway management are not included, so as to avoid conflict with future practitioners’ choices of airway management techniques. The form is then given to the patient to complete (including the name of the primary care physician), sign, and mail in (or fax to) the MedicAlert Foundation along with a check or credit card information for the enrollment fee. The amount of the enrollment fee depends on which type of membership the patient selects. For patients who are unable to pay for membership, the MedicAlert Foundation will enroll them for free if the completed enrollment form is accompanied by a statement of financial need that is written on official letterhead paper and signed by the anesthesiologist or other provider.

D Characteristics of Registry Patients

Between 1992 and 1994, more than 250 adult and pediatric patients throughout the United States were enrolled in the MedicAlert Foundation National Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry. Their characteristics were as follows: ASA classes I and II, 54%; ASA classes III and IV, 46%; ASA class V, 0%. For airway management in these patients, conventional laryngoscopy was successful only about 20% of the time. These patients had 39 reported adverse outcomes: cancellations, 9 (23%); dental trauma, 3 (8%); desaturation, 7 (18%); soft tissue trauma, 11 (28%); cardiovascular compromise, 2 (5%); and other, 7 (18%). Patients were enrolled from private and academic institutions, from outpatient surgical centers, and by self-referral.47 By 2003, there were approximately 7020 patients enrolled in the MedicAlert National Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry.34

E Benefits of the Registry

The Registry increases practitioner protection from liability by improving provider-patient communication. Enrollment gives providers an opportunity to inform patients of their airway difficulties and adverse events while offering a way to protect them during subsequent events, and this is perceived as a positive reflection of the provider’s concern. As described previously, a 1994 survey of Johns Hopkins patients found that, despite experiencing adverse outcomes, 100% of patients felt that enrollment in the Registry gave them a sense of comfort that future care providers would understand their condition.31 In the operating room, this difficult airway/intubation knowledge may help avoid adverse outcomes and malpractice suits.

The cost of initial enrollment in the Registry may be justified by future cost savings realized by the patient and the provider or institution. Knowing that a patient was previously identified as having a difficult airway or difficult intubation and what techniques were used could promote the cost-effective use of equipment and operating room time and decrease the incidence of cancellations. A 10-month study of 690 patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery at the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions as the first procedure of the day looked at charges for anesthesia preparation time (i.e., anesthesiologist’s professional fee, anesthesia resident’s charge, drug and supply charges, and operating room time charges). Of these patients, 684 had no airway difficulty (control group) and 6 had difficult airway/intubation and were subsequently enrolled in the National Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry. There was a mean charge of $990.71 for the control group patients and a mean charge of $1578.24 for the difficult airway/intubation patients, representing a 59% increase over the control group.48

VIII Conclusions

Information is the lifeblood of modern medicine, and health information technology is its circulatory system.49 Quality improvements in the process of managing difficult airway/intubation situations (methods to identify patients, algorithms, equipment, airway teams) should be vigorous and ongoing but should be accompanied by improvements in how airway information is documented and disseminated. Once a patient with a difficult airway/intubation is identified, documentation of the airway management is critical and should include the specifics of successful and unsuccessful techniques, the skill level of the practitioner, and the clinical setting where the event occurred. The patient’s in-house EMR, which can be accessed by multiple care providers and is linked to a difficult airway/intubation patient wristband and an alert on the facesheet, ensures that the patient is recognized as such throughout the initial episode of care.

IX Clinical Pearls

• The MedicAlert Foundation, founded in 1965 and endorsed by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) in 1979, is the only 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that provides a comprehensive medical service to members, in the form of visible medical ID, a separate wallet card, a Web-accessible personal health record, and a 24/7 live emergency response service.

• In 1992, the MedicAlert Foundation National Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry was created to facilitate uniform documentation and effective dissemination of standardized critical information related to complex airway management.

• The ASA Practice Guidelines for the Difficult Airway recommend the following components for dissemination of critical airway information: (1) a written report or letter to the patient, (2) a report in the medical record, (3) a chart flag, (4) communication with the patient’s surgeon or primary caregiver, and (5) a notification bracelet or equivalent identification device. MedicAlert is currently the only organization that can readily provide this service.

• The consequences of a difficult airway/intubation may include minor or major adverse medical events or death, professional liability to the practitioner, and direct and indirect costs to the patient and health care system. Difficult airway/intubation still accounts for the highest percentage of closed claims in anesthesia.

• By 2010, the MedicAlert National Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry included more than 11,000 active members with the condition of “difficult airway.”

• Individuals can become members of the MedicAlert Foundation by calling 1-800-ID-ALERT or by visiting the Web site (www.medicalert.org [accessed April 2012]). There is an annual enrollment fee, but if a person cannot afford the fee, a health care provider may contact MedicAlert and request that the fee be waived.

• The Foundation plans to have an updated National Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry form available on both their Web site and that of the Society for Airway Management (www.samhq.com [accessed April 2012]) by the summer of 2012.

All references can be found online at expertconsult.com.

1 American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:1269–1277.

7 Koenig HM. No more difficult airway, again! Time for consistent standardized written patient notification of a difficult airway. Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation Newsletter. 2010;Summer:1–6.

11 Mark LJ, Beattie C, Ferrell CL, et al. The difficult airway: Mechanisms of effective dissemination of critical information. J Clin Anesth. 1992;4:247–251.

31 Cherian M, Mark L, Schauble J, et al. The national MedicAlert(r) difficult airway/intubation registry: Patient safety and patient satisfaction [abstract]. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists, San Francisco, CA. October 1994.

34 Trentman TL, Frasco PE, Milde LN. Utility of letters sent to patients after difficult airway management. J Clin Anesth. 2004;16:247–261.

37 Foley LJ, Sands D, Feinstein D, et al. Effect of difficult airway (DA) registry on subsequent airway management experience in the first 2 years of a DA registry. Anesthesiology. 1996;89:A1220.

41 The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. HITECH program. Available at http://www.healthit.hhs.gov (accessed April 2012)

44 Roman P, Dahab Y, Herzer K, et al. MedicAlert(r) national registry for difficult airway/intubation: A 1992–2010 perspective [abstract]. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Airway Management, Chicago, IL. September 16, 2010.

48 Mark LJ, Schauble J, Turley SM, et al. The MedicAlert(r) national difficult airway/intubation registry: Technology that pays for itself [abstract]. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Technology in Anesthesia, Phoenix, AZ. January 1995.

1 American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:1269–1277.

2 American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Guidelines for Management of the Difficult Airway. Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway. Anesthesiology. 1993;78:597–602.

3 Caplan RA, Posner K, Ward RJ, et al. Adverse respiratory events in anesthesia: A closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology. 1990;72:828–833.

4 Wilson ME, Spiegelhalter D, Robertson JA, et al. Predicting difficult intubation. Br J Anaesth. 1988;61:211–216.

5 Rose DK, Cohen MM. The airway: Problems and predictors in 18,500 patients. Can J Anaesth. 1994;41:372–383.

6 Naguib M, Scamman FL, O’Sullivan C, et al. Predictive performance of three multivariate difficult tracheal intubation models: A double-blind, case-controlled study. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:818–824.

7 Koenig HM. No more difficult airway, again! Time for consistent standardized written patient notification of a difficult airway. Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation Newsletter. 2010;Summer:1–6.

8 Combes X, Jabres P, Margenet A, et al. Unanticipated difficult airway management in the prehospital emergency setting: Prospective validation of an algorithm. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:105–110.

9 Martin LD, Mhye JM, Shanks AM, et al. 3,423 Emergency tracheal intubations at a university hosptial: Airway outcomes and complications. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:42–48.

10 American Society of Anesthesiologists. Join ASA. Available at http://www.asahq.org/For-Healthcare-Professionals/About-ASA/Join-ASA (accessed April 2012)

11 Mark LJ, Beattie C, Ferrell CL, et al. The difficult airway: Mechanisms of effective dissemination of critical information. J Clin Anesth. 1992;4:247–251.

12 Combes X, Le Roux B, Suen P, et al. Unanticipated difficult airway in anesthetized patients: Prospective validation of a management algorithm. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:1146–1150.

13 Heidegger T, Gerig HJ, Ulrich B, et al. Validation of a simple algorithm for tracheal intubation: Daily practice is the key to success in emergencies—An analysis of 13,248 intubations. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:517–522.

14 Jensen AG, Callesen T, Hagemo JS, et al. Scandinavian clinical practice guidelines on general anesthesia for emergency situations. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2010;54:922–950.

15 Barron FA, Ball DR, Jefferson P, et al. Airway alerts: How UK anaesthetists organise, document, and communicate difficult airway management. Anaesthesia. 2003;58:73–77.

16 Amathieu R, Combes X, Abdi W, et al. An algorithm for difficult airway management, modified for modern optical devices (Airtraq(tm) Laryngoscope; LMA CTrach(tm)): A 2-year prospective validation in patients for elective abdominal, gynecologic, and thyroid surgery. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:25–33.

17 Levitan RM. Salvaging the difficult airway: A practical approach. Emergency Medicine Learning and Resource Center. Available at http://www.femf.org/education/ClinCon01/Levitan.htm (accessed April 2012)

18 Orebaugh SL. Difficult airway management in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2002;22:31–48.

19 Walls RM. The emergency airway algorithms. In: Walls RM, ed. Manual of airway management. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2000:16–25.

20 Schmidt U, Eikermann M. Organizational aspects of difficult airway management: Think globally, act locally. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:3–6.

21 Oxygenation, not intubation, does matter [editorial]. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:7–9.

22 Hillel A, Mon KS, Steppan J, et al. The difficult airway response team (DART): A case for proceeding to the operating room [abstract]. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Anesthesia Research Society, Vancouver, Canada. May 2011.

23 Berkow LC, Greenberg RS, Kan KH, et al. Need for emergency surgical airway reduced by a comprehensive difficult airway program. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:1860–1869.

24 Mon KS, Hillel A, Herzer K, et al. The difficult airway response team (DART): A multidisciplinary approach to difficult airway emergencies [abstract. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Anesthesia Research Society, Vancouver, Canada May 2011.

25 American Society of Anesthesiologists Committee on Professional Liability. Preliminary study of closed claims. ASA Newsletter. 1988;52:8.

26 Mark L, Drake J. Professional liability and patient safety: The MedicAlert(r) National Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry. Anesthesiol Alert. 1994;3:1.

27 Peterson GN, Domino KB, Caplan RA, et al. Management of the difficult airway: A closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:33–39.

28 Benumof JL. Difficult laryngoscopy: Obtaining the best view. Can J Anaesth. 1994;41:361–365.

29 Mort TC. Emergency tracheal intubation: Complications associated with repeated laryngoscopic attempts. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:607–613.

30 How to avoid small complaints about quality of care [editorial]. Maryland BPQA (Board of Physician Quality Assurance) Newsletter. 1993;1(4):1.

31 Cherian M, Mark L, Schauble J, et al. The national MedicAlert(r) difficult airway/intubation registry: Patient safety and patient satisfaction [abstract]. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists, San Francisco, CA. October 1994.

32 Mark LJ, Marsh BR. MedicAlert(r), communications, confidentiality, and other medicolegal considerations. In: Norton ML, Brown AC. Atlas of the difficult airway: A source book. ed 2. St Louis: Mosby; 1991:17–34.

33 Foley L, Feinstein D, Sands D, et al. Computerized in-hospital immediate access difficult airway/intubation registry [abstract]. Anesthesiology. 1995;83:A1124.

34 Trentman TL, Frasco PE, Milde LN. Utility of letters sent to patients after difficult airway management. J Clin Anesth. 2004;16:247–261.

35 Francon D, Bruder N. Why should we inform patients after difficult tracheal intubation? Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2008;27:426–430.

36 Mark LJ, Foley LJ. Effective dissemination of critical airway information: The MedicAlert(r) national difficult airway/intubation registry. In: Benumof J, Hagberg CA. Benumof’s airway management: Principles and practice. ed 2. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2007:1267.

37 Foley LJ, Sands D, Feinstein D, et al. Effect of difficult airway (DA) registry on subsequent airway management experience in the first 2 years of a DA registry. Anesthesiology. 1996;89:A1220.

38 HealthData Management. Beth Israel’s in-house EHR certified. http://www.healthdatamanagement.com/news/certification, January 24, 2011. Available at (accessed April 2012)

39 Dimick C. First steps to patient-centered care: Meaningful use focuses on industry baby steps. J AHIMA (American Health Information Management Association). 2011;82:20–24.

40 PricewaterhouseCoopers HRI consumer survey. A limited view for patients. J AHIMA. 2011;82(2):20–24.

41 The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. HITECH program. Available at http://www.healthit.hhs.gov (accessed April 2012)

42 Maryland Health Care Commission HIE Policy Board Meeting. http://mhcc.maryland.gov/electronichealth/hie_policy_board/crisp_policy_board_120809.pdf, December 8, 2009. Available at (accessed April 2012)

43 Gibby GL, Mark LJ, Drake J. Effectiveness of Teleforms scan-based input tool for difficult airway registry: Preliminary results [abstract]. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Technology in Anesthesia, Phoenix, AZ. January 1995.

44 Roman P, Dahab Y, Herzer K, et al. MedicAlert(r) national registry for difficult airway/intubation: A 1992–2010 perspective [abstract]. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Airway Management, Chicago, IL September 16, 2010.

45 ADAIR. Austrian Difficult Airway/Intubation Review. http://www.adair.at, 1999. Available at (accessed April 2012)

46 Rosenstock C, Rasmussen LS. The Danish difficult airway registry and preoperative respiratory airway assessment. Ugeskr Laeger. 2005;167:2543–2544.

47 Mark LJ, Gibby G, Fleisher L, et al. Practice guidelines to clinical practice: MedicAlert(r) difficult airway/intubation registry [abstract]. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists, San Francisco, CA. October 1994.

48 Mark LJ, Schauble J, Turley SM, et al. The MedicAlert(r) national difficult airway/intubation registry: Technology that pays for itself [abstract]. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Technology in Anesthesia, Phoenix, AZ. January 1995.

49 Blumenthal D. Launching HITECH. E-pub ahead of print, December 30. http://healthcarereform.nejm.org, 2009. Available at (accessed April 2012)

Appendix A

Persons can become members of the MedicAlert® Foundation by:

1. Calling the MedicAlert® Foundation at 1-800-ID-ALERT™ (1-800-432-5378)

2. Visiting the MedicAlert® Foundation Web site at www.medicalert.org

3. E-mailing the MedicAlert® Foundation at customer_service@medicalert.org

Completed National Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry enrollment forms can be:

Additional National Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry enrollment forms can be obtained by:

1. Visiting the MedicAlert® Foundation Web site at www.medicalert.org

2. E-mailing the MedicAlert® Foundation at customer_service@medicalert.org

3. Calling the MedicAlert® Foundation at 1-800-ID-ALERT™ (1-800-432-5378)

For additional information regarding the National Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry:

1. Visit the MedicAlert® Foundation website at www.medicalert.org

2. Call MedicAlert® Foundation, 1-800-ID-ALERT™ (1-800-432-5378)

3. Contact Lynette J. Mark, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 600 North Wolfe St., Tower 711, Baltimore, MD 21287-8711