Chapter 20

Edema (Case 13)

Ellena Linden MD and Dennis Finkielstein MD

Case: A 55-year-old man presents with complaints of increasing lower extremity swelling over the past several months. He otherwise feels well and has no other complaints. He does not have chest pain but does become short of breath when climbing stairs; he attributes this to lack of exercise and deconditioning. He has no dyspnea at rest. His past medical history is unremarkable. He does not take any medications on a regular basis. This man does not smoke or use alcohol currently, although he admits to having been an alcoholic in the past. He does not use recreational drugs. On physical exam he appears well. Blood pressure is 110/60 mm Hg, and heart rate is 80 beats per minute. His weight is 80 kg, up from 72 kg a few months ago. Cardiovascular, pulmonary, and abdominal exams are unremarkable. There is significant pitting edema of both lower extremities.

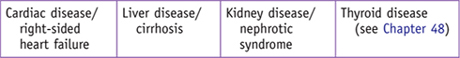

Differential Diagnosis

Speaking Intelligently

Nephrotic syndrome is a constellation of findings, which includes nephrotic-range proteinuria (defined as urinary protein excretion of greater than 3.5 g in a 24-hour period), edema, hypoalbuminemia, and dyslipidemia. Proteinuria in nephrotic syndrome might be the only sign of renal disease; these patients often have normal creatinine levels, lack of hematuria, and normal-appearing kidneys on radiologic imaging. Patients with nephrotic syndrome are predisposed to thromboembolic disease.

PATIENT CARE

Clinical Thinking

• Attempt to identify the cause.

• Look for evidence of systemic disease; if one is not found, it is likely that the nephrotic syndrome is due to a purely renal disease.

History

• Cardiac dysfunction: Does the patient have orthopnea or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea?

• Thyroid disease: Is the patient fatigued? Is there constipation? Cold intolerance? Weight gain?

• Liver disease: Is there history of hepatitis, cirrhosis, or jaundice?

• Kidney disease: Is there hematuria?

Physical Examination

• Is the edema localized or generalized, pitting or nonpitting, bilateral or unilateral?

• Cardiac function: Is there jugular venous distension? Are there murmurs? Is there pulmonary edema?

• Venous obstruction: Is the edema unilateral, increasing the suspicion of deep venous thrombosis?

Tests for Consideration

| Clinical Entities | Medical Knowledge |

|

Minimal-Change Disease |

|

|

Pφ |

Another name for minimal-change disease is nil disease. The reason for the name is that the kidney biopsy looks normal when viewed under light microscopy. However, on electron microscopy, patients with minimal-change disease have diffuse fusion, or effacement, of epithelial cell foot processes. |

|

TP |

Minimal-change disease is generally thought of as a childhood disease. While it is more common in children, it can occur at any age. The typical presentation is that of a sudden onset of classic nephrotic syndrome: nephrotic-range proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, edema, and dyslipidemia. Serum creatinine is usually normal. |

|

In a child who presents with classic nephrotic syndrome, the diagnosis of minimal-change disease is presumed because of its high prevalence in this age group. Kidney biopsy is usually not done, and empirical therapy is initiated. In an adult presenting with nephrotic syndrome, however, a biopsy is obtained and the diagnosis of minimal-change disease is based on the biopsy findings. Minimal-change disease is usually idiopathic but can be associated with medications (e.g., NSAIDs) and certain malignancies. |

|

|

Tx |

Glucocorticoids are the mainstay of therapy in both children and adults. See Cecil Essentials 29. |

|

Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) |

|

|

Pφ |

FSGS is characterized by scarring of some of the glomeruli (focal) in some parts of the glomerulus (segmental). This scarring can be seen by light microscopy. Electron microscopy shows effacement of epithelial foot processes (similar to that found in minimal-change disease) in addition to the scarring already seen on the light microscopy. |

|

TP |

FSGS usually presents as an abrupt onset of nephrotic syndrome. Unlike the typical nephrotic syndrome, these patients often have hypertension and sometimes microscopic hematuria. FSGS is more common in adults. It is also more common in African-American patients. |

|

Dx |

Diagnosis is based on typical presentation followed by kidney biopsy that shows the typical lesion. Once the diagnosis of FSGS is made, it is important to look for secondary causes such as HIV and reflux nephropathy. |

|

Tx |

Treatment of primary FSGS involves steroids and, in some cases, cyclosporine. Antiproteinuric therapy with an ACE inhibitor or ARB is advised for all proteinuric diseases. See Cecil Essentials 29. |

|

Membranous Nephropathy |

|

|

Pφ |

The typical finding on light microscopy is diffuse thickening of the glomerular basement membrane. Special stains can illustrate that this thickening is due to “spikes” caused by the subepithelial deposits of IgG and possibly complement. Electron microscopy confirms the presence of subepithelial deposits. |

|

Patients usually present with nephrotic syndrome with variable degrees of proteinuria. Patients are frequently hypercoagulable and can present with renal vein thrombosis or deep vein thrombosis, occasionally complicated by a pulmonary embolism. |

|

|

Dx |

Diagnosis can be made only by examining tissue obtained by a kidney biopsy. Once the diagnosis is established, secondary causes such as lupus and hepatitis B need to be excluded. Membranous nephropathy can also be associated with malignancy. Patients should undergo age-appropriate cancer screening. |

|

Tx |

About one third of patients undergo spontaneous remission, one third remain unchanged, and one third continue to progress, eventually developing end-stage renal disease. Because of the high rate of spontaneous remission, most nephrologists will wait approximately 6 months before initiating treatment with steroids and either cyclophosphamide or chlorambucil. See Cecil Essentials 29. |

|

Amyloidosis |

|

|

Pφ |

Amyloid fibrils cause disease by being deposited extracellularly in various organs and interfering with that organ’s function. Amyloid can involve virtually any organ including heart, liver, kidneys, central nervous system, and blood vessels. On light microscopy of renal tissue, amyloid can be seen as amorphous hyaline material. Electron microscopy, however, will show randomly organized amyloid fibrils. |

|

TP |

Typical presentation depends on the organs involved. When limited to the kidney, amyloid presents as classic nephrotic syndrome. |

|

Dx |

Diagnosis relies on obtaining tissue biopsy of the most easily accessible involved organ, which often is the kidney. Once tissue is obtained, the type of amyloid can be determined. Some types of amyloid are primary, some are hereditary, and some are acquired secondary to systemic diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis. |

|

Tx |

Treatment of secondary amyloid is aimed at the underlying disease. Treatment of primary amyloid can involve hematopoietic cell transplantation, melphalan (an alkylating agent), and steroids. See Cecil Essentials 29, 51, 90. |

|

Pφ |

Diabetic nephropathy is the end result of various pathogenic insults occurring as a result of diabetes mellitus, including intraglomerular hypertension, formation of advanced glycation end products, and proliferation of various cytokines and vascular growth factors. Microscopically, kidney biopsy shows thickening of basement membrane, expansion of the mesangial matrix, and glomerular sclerosis, which often has a nodular appearance (known as Kimmelstiel-Wilson lesions). |

|

TP |

In patients with onset of heavy proteinuria with long-standing diabetes and a prior history of microalbuminuria, it usually takes longer than 15 years from the development of diabetes to the development of diabetic nephropathy. Patients with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes are affected. |

|

Dx |

Diagnosis is made based on the typical presentation. Biopsy is usually not necessary unless some features of the presentation are atypical or inconsistent with diabetic nephropathy. Keep in mind that type 2 diabetics are often diagnosed many years after the onset of diabetes and may develop diabetic nephropathy shortly after diagnosis of diabetes. |

|

Tx |

The mainstay of treatment is achieving excellent glycemic as well as blood pressure and lipid control. ACE inhibitors and ARBs both have renoprotective effects that are independent of their antihypertensive effect. See Cecil Essentials 29. |

Practice-Based Learning and Improvement: Evidence-Based Medicine

Title

Development and progression of nephropathy in type 2 diabetes: the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study

Authors

Adler AI, Stevens RJ, Manley SE, et al.

Institution

Diabetes Trials Unit, Oxford Centre for Diabetes, Endocrinology and Metabolism, University of Oxford, Oxford, and South Cleveland Hospital, Cleveland, United Kingdom

Reference

Kidney Int 2003;63:225–232

Problem

The goal is to prospectively study the progression of nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes from stage to stage.

Intervention

None, this was an observational part of the large United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS). UKPDS was designed to compare efficacy of different treatment regimens on glycemic control and complications of diabetes in newly diagnosed patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Outcome/effect

Substantial numbers of patients with type 2 diabetes develop microalbuminuria, with 25% of patients affected by 10 years from diagnosis. Relatively fewer patients develop macroalbuminuria, but in those who do, the death rate exceeds the rate of progression to worse nephropathy.

Historical significance/comments

Largest study to date of progression of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes

Interpersonal and Communication Skills

Communicate Effectively in the Face of Patient or Family Demands for Unnecessary Procedures

A patient under your care in the ICU has metastatic colon cancer and presents with hypotension and AKI. His prognosis is extremely poor, but his family is insisting on urgent dialysis. What do you do? Easy access to health care information is usually helpful, but direct-to-consumer information may not be evidence-based. Patients are also surrounded by conflicting information from friends and family. When your patient or family demands specific procedures that are unlikely to be effective, it is often difficult to say “No” in a caring, responsible way. The best approach is to validate their fears and then to present your reasons why a particular procedure is not warranted at this time. It may be difficult to reassure the family when the outcome may not be optimal. However, these discussions are important to ensure compassionate care.

Professionalism

Demonstrate Commitment to Self-Care

It is important not to overcommit to a patient. For example, suppose your patient underwent a recent kidney biopsy, which was later complicated and required admission to the hospital to treat an infection at the biopsy site. This patient is emergently admitted to the hospital on a Friday evening as you are about to leave town for a previously scheduled weekend away with your family. One can see how easy it would be to cancel your plans and follow through with this case. However, a commitment to your personal self-care, which includes time off, vacations, and stress reduction, is extremely important. Physicians have a high rate of burnout, divorce, and stress-related illness. Having protected time goes a long way in the care of your patients. Explain to the patient that your colleague will be on call while you are away and that you have shared all of the important information needed for care, and that you will, of course, follow up on your return.

Systems-Based Practice

Permitting and Restricting Patient Care: Be Aware of Societal Implications

The treatment of many renal diseases, especially in the advanced stage, can be expensive. These treatments often include costly medications and long-term dialysis therapy. At present, dialysis is offered to everyone who needs it as part of the Medicare entitlement for end-stage renal disease that has been in effect since 1972; by the end of 2008, there were about 382,000 patients undergoing dialysis in the United States. There are data showing that in some elderly patients with multiple co-morbidities, dialysis does not increase survival, suggesting that further discussion about resource allocation is needed. Given the limited health care resources and the ever increasing demand for them, it is likely that we, as a society, will have to face restricting resources or allocating them based on some predetermined criteria.