57 Eczema and psoriasis

Eczema

Pathology and clinical features

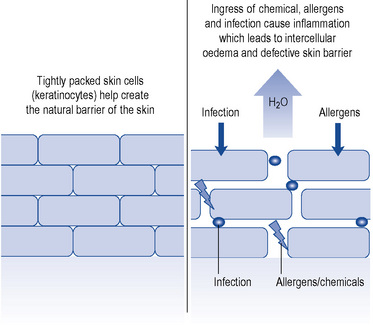

Acute eczema is an inflammatory process leading to oedema in the epidermis. The oedema is seen histologically in the epidermis as ‘spongiosis’. Oedema manifests as fluid that collects into tiny blisters which may then coalesce. This is seen histologically as intraepidermal vesicles and clinically as pompholyx blisters on thicker palmar and plantar skin, and as excoriated, ruptured crusted vesicles elsewhere. Tightly packed keratinocyte cells in the epidermis usually prevent transepidermal fluid loss and the entry of pathogens. This barrier function of the skin is lost in eczema. A schematic diagram demonstrating the normal skin epidermis and the effects on the barrier function during an acute eczema flare is shown in Fig. 57.1.

In the chronic form of eczema, prolonged rubbing and scratching results in a thickened epidermis and an increase in the upper horny cell layer of keratin, termed hyperkeratosis. Clinically, the skin appears thick, leathery, scaly and ‘lichenified’ with exaggerated skin markings, like tree bark (Fig. 57.2). Both acute and chronic stages are accompanied by a heavy chronic inflammatory cell infiltration of the dermis and epidermis. The main consequent symptom of these pathological processes is itch. The dictum of ‘if it’s not itchy, it’s not eczema’ holds true.

Clinical types

Atopic eczema

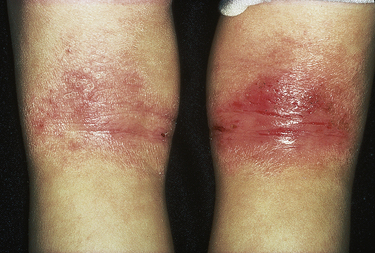

Atopic eczema is diagnosed clinically and the criteria for definition include chronic itchy skin with three or more of the following: a history of flexural involvement of the skin creases, visible flexural involvement, dry skin, other atopic disease or onset within the first 2 years of life. The clinical course and distribution change through puberty and adulthood. In infants, common areas affected are face, neck and nappy area. Through childhood, flexural sites such as folds of the elbows and backs of the knees are classically involved (see Fig. 57.3). Symptoms usually improve with age and approximately 60% have resolution of symptoms by the age of 16.

Exacerbating factors

A number of factors can aggravate atopic eczema:

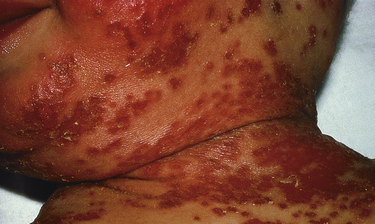

The commonest trigger in the paediatric population is secondary infection, either bacterial or viral. Bacterial colonisation is common on the skin of those with atopic dermatitis and may result in the invasive infection triggering an acute flare. Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus spp. are most often responsible (Fig. 57.4).

Contact dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis

Many common compounds can lead to ACD. The most common compounds implicated are:

The standard confirmatory investigation is patch testing and is used to differentiate allergic from ICD. This involves application of a standard, with or without a specialised range of compounds, to the patient’s back over 72 h. This is followed by examination for a cutaneous reaction at day 2 and day 4. Identification of relevant compounds allows the patient to avoid the substance in the future, and this will hopefully reduce symptoms. Common areas of the body affected by ACD, with corresponding probable sensitisers, are listed in Table 57.1.

Table 57.1 Common locations for allergic contact dermatitis and possible sensitisers

| Location | Possible sensitising agents |

|---|---|

| Periorbital | Airborne allergens, nail polish, contact lens solution |

| Umbilicus | Nickel hypersensitivity to belt/jean button |

| Neck | Antiseptic in soap, cosmetics |

| Hairline | PPD in hair dye, hair perming solution |

| Hands | Latex or rubber accelerators in gloves, nickel, fragrances, protein contact dermatitis in food preparation, irritant contact dermatitis due to water |

PPD, p-phenylediamine.

Irritant contact dermatitis

This is the most common form of occupational dermatitis and the commonest cause of hand eczema (Fig. 57.5). Unlike ACD, ICD is not immunologically mediated. The mechanism involves disruption of the epidermal permeability barrier and a direct cytotoxic effect depending on the irritant. Patients with pre-existing epidermal barrier dysfunction such as atopic eczema are at higher risk. The occupation of the individual may also be a risk factor, especially those working as builders, hairdressers, gardeners, healthcare workers and chefs. Irritants include detergents, oils, water, inorganic acids, alcohols and plastics. Preventative skin care is key and this includes the use of barriers such as emollients or cotton gloves in addition to avoiding suspected irritants.

Treatment

Emollients

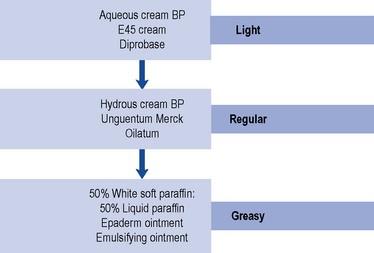

Emollients, topical hydrating agents consisting of fat or oil to soften the skin, are the mainstay of eczema management. Emollients are effective first-line treatments for all types of eczema, and regular, liberal use will reduce topical steroid requirements. The greasier products have more emollient effect (see Fig. 57.6). They are often underused and the need to educate the patient regarding use of sufficient quantities is vital. Dry skin is aggravated by soap and bath products, and therefore an emollient soap substitute for washing is advisable.

Topical corticosteroids

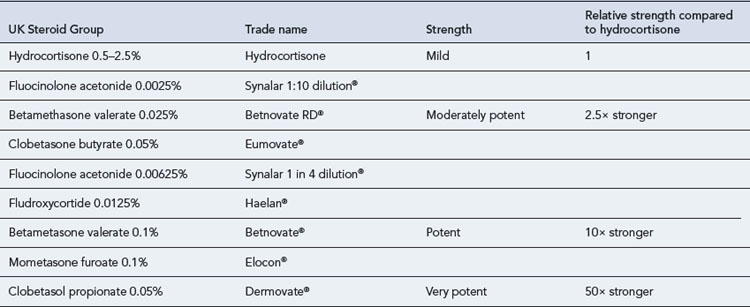

Topical steroids are classified into four main groups according to potency: mild, moderately potent, potent and very potent (Table 57.2). The choice of topical steroid is dependent on the site and severity of skin disease. Potent and very potent steroids should be avoided on delicate sites such as the face, genitals and flexures. The periorbital region should be treated with caution due to the thin skin increasing the likelihood of absorption and risk of cataracts or glaucoma. Treatment should be reviewed regularly and tailored accordingly. It is also important to remember that any form of occlusion will increase the absorption of steroid applied.

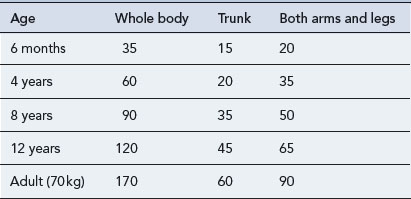

Local and systemic side effects are extremely rare with appropriate use and duration of topical steroid treatment. Patients should be advised to spread preparations thinly either once or twice daily. The recommended amount used can be quantified using a fingertip unit (Fig. 57.7). The quantity in this unit is sufficient to cover an area the size of two adult palms. Table 57.3 details the quantities for application to different sites required for twice-daily treatment for 1 week.

Calcineurin inhibitors

Pimecrolimus 1% cream (Elidel®) is indicated for short-term or intermittent long-term use in mild to moderate atopic dermatitis. Studies have shown that it is effective, well tolerated and has minimal adverse effects in the long-term control of eczema in children aged over 2 years (Langley et al., 2008). Furthermore, this has resulted in the reduced use of topical steroids leading to a lower risk of steroid-induced side effects (Kapp et al., 2002).

Systemic therapies

Methotrexate

Methotrexate is occasionally used in unresponsive adult atopic eczema, but randomised controlled trials are lacking. A small prospective trial has shown that methotrexate can be effective and well tolerated as a second-line therapy for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic eczema in adults (Weatherhead et al., 2007).

Phototherapy

Phototherapy can be effective in select cases of atopic dermatitis. Narrow-band UVB is the therapy of choice (Gambichler et al., 2005; Meduri et al., 2007). The potential side effects of all types of phototherapy include burning, premature ageing and a small increased risk of skin cancer. A small proportion of patients have photosensitive eczema, and this should be determined by taking a detailed patient history before prescribing phototherapy treatment. A treatment course requires a patient to attend two or three times a week for at least 6 weeks.

Dietary supplements

Interactions with drugs used in the treatment of eczema and psoriasis are shown in Table 57.4.

Table 57.4 Interactions with drugs used in the treatment of eczema and psoriasis

| Interacting drug | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|

| Methotrexate | Aspirin | Increased plasma concentration and toxicity of methotrexate |

| NSAIDs | Increased plasma concentration and toxicity of methotrexate | |

| Probenecid | Increased plasma concentration and toxicity of methotrexate | |

| Phenytoin | Increased bone marrow toxicity | |

| Sulphonamides | Increased toxicity | |

| Trimethoprim | Increased antifolate effect of methotrexate | |

| Azathioprine | Allopurinol | Enhanced effect and toxicity of azathioprine |

| Warfarin | Inhibition of anticoagulant effect | |

| Cimetidine | Enhanced myelosuppression | |

| Indometacin | Increased risk of leucopenia | |

| Ciclosporin | NSAIDs | Increased risk of nephrotoxicity |

| Aminoglycosides | Increased risk of nephrotoxicity | |

| Co-trimoxazole | Increased risk of nephrotoxicity | |

| Ciprofloxacin | Increased risk of nephrotoxicity | |

| Ketoconazole | Increased plasma concentration of ciclosporin | |

| Itraconazole | Increased plasma concentration of ciclosporin | |

| Erythromycin | Increased plasma concentration of ciclosporin | |

| Oral contraceptives | Increased plasma concentration of ciclosporin | |

| Calcium channel blockers | Increased plasma concentration of ciclosporin | |

| Phenytoin | Decreased plasma concentration of ciclosporin | |

| Carbamazepine | Decreased plasma concentration of ciclosporin | |

| Rifampicin | Decreased plasma concentration of ciclosporin | |

| Acitretin | Methotrexate | Increased plasma concentration of methotrexate |

(courtesy of M. Carr)

Patient care

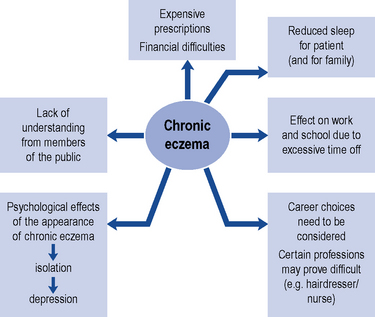

It is important to recognise that eczema affects many aspects of a patient’s life and has considerable effects on the family. Quality-of-life factors affected include body image, irritability and loss of sleep due to profound itch and limitations to work and hobbies (Fig. 57.8). A multidisciplinary approach is often needed in overcoming these issues, and healthcare workers including primary care doctors, dermatologists, specialist nurses, pharmacists and teachers may be involved. Patients with eczema should aim to lead as normal a life as possible, and school staff and employers can play an important part in achieving this goal.

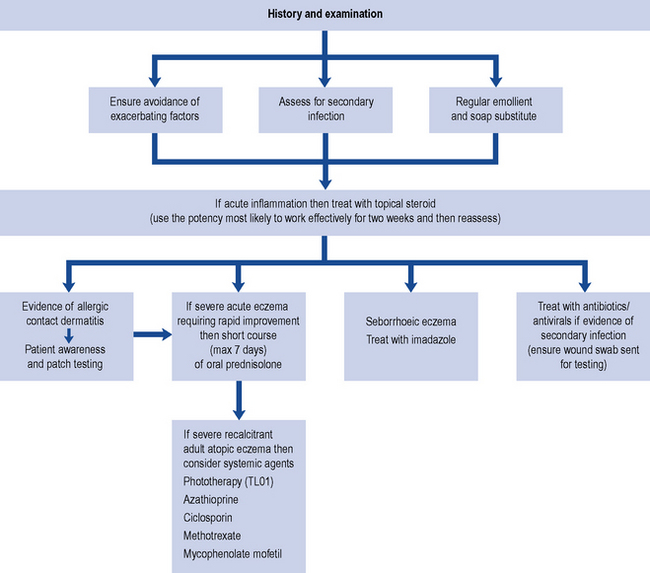

Patient and parental education is important as treatments are designed to control and manage the disease. Although atopic eczema is likely to improve throughout childhood, expectations of an immediate cure need to be addressed. Advice and support through contact with other patients and their families can be obtained from the National Eczema Society (www.eczema.org). An algorithm for the management of eczema is shown in Fig. 57.9.

Psoriasis

Precipitating factors

Alcohol and smoking

Smoking is strongly associated with palmoplantar psoriasis; up to 95% of patients with this variant are smokers at disease onset. Smoking cessation should be actively addressed due to a likely improvement in disease status and associated risk reduction of ischaemic heart disease. It has been suggested that psoriasis, particularly if severe, may be an independent risk factor for atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction and stroke (Mehta et al., 2010).

Emotional stress

Anecdotal observations and frequent patient reports identify stress as an important trigger factor for psoriasis. Clinical evidence has demonstrated that the onset and severity of psoriasis can correlate with prior stress (Kirby et al., 2008). Furthermore, psychological distress and depression can occur as a consequence of psoriasis.

Pathology and clinical features

The clinical features of psoriasis, well-demarcated, erythematous scaly plaques, are explained by the histological features (Fig. 57.10). Common sites affected include the scalp, buttocks, elbows, knees and nails.

Guttate psoriasis

Guttate psoriasis is more commonly seen in children and young adults and is characterised by a widespread scaly eruption of small ‘teardrop-like’ scaly plaques (Fig. 57.11). The presentation is often acute and can appear 10–14 days after a streptococcal upper respiratory tract infection. Topical treatments or UVB phototherapy are usually effective. Spontaneous resolution is common; however, guttate psoriasis may be the first manifestation of psoriasis in predisposed individuals.

Palmoplantar psoriasis

At these sites on the palms and soles, there is sharp demarcation of the involved areas (Fig. 57.12). Palmoplantar psoriasis can take two forms: either inflamed hyperkeratotic fissured skin which can be very painful or sterile pustules on an erythematous base which dry to leave small brown macules (palmoplantar pustulosis). The pustular form is much commoner in smokers.

Erythrodermic psoriasis

Erythroderma, or exfoliative dermatitis, is a severe, potentially life-threatening condition in which more than 90% of the body surface is red and scaly (see Fig. 57.13). This can occur as a consequence of either eczema or psoriasis. Skin function is impaired and patients suffer dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, temperature dysregulation and serious secondary infection. These patients need urgent hospital admission, medical supportive therapy and topical treatment. Initially, bland emollients such as white soft paraffin and mild to moderate topical steroids should be used. Underlying conditions, such as psoriasis, can then be treated with appropriate systemic agents.

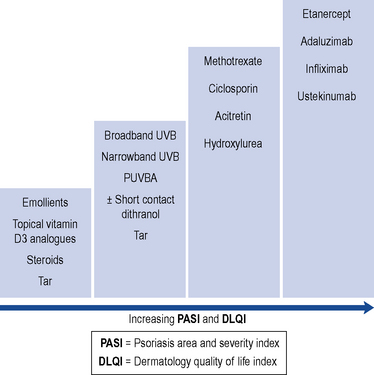

Systemic therapy

Systemic therapy is indicated in severe widespread psoriasis, intolerant of or rapidly relapsing after topical therapy and phototherapy. Objective measures of disease severity and impact on quality of life are used routinely to assess need for systemic therapy and treatment response and include the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) and the Dermatology Quality of Life Index (DLQI). Systemic treatments commonly prescribed in psoriasis include methotrexate, acitretin and ciclosporin. Drug interactions are important and a detailed patient drug history is important. New biologic agents are used in severe disease which is unresponsive to oral immunosuppressant treatment. Common adverse effects and monitoring requirements of systemic treatments of eczema and psoriasis are presented in Table 57.5.

Table 57.5 Common adverse effects and monitoring requirements for systemic treatments of eczema and psoriasis

| Therapy | Adverse Effects | Monitoring requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Methotrexate | Hepatic fibrosis; myelosuppression; nausea; pulmonary fibrosis; teratogenic (contraindicated in both males and females for 4 weeks before and 3 months after treatment) | FBC |

| U&E | ||

| LFT | ||

| Pro-collagen III peptide (P3NP) | ||

| ±Liver biopsy | ||

| Chest X-Ray (screening) | ||

| Hydroxyurea | Myelosuppression; skin reaction; teratogenic; liver toxicity (narrow therapeutic window) | FBC |

| U&Es | ||

| LFT | ||

| Ciclosporin | Renal nephrotoxicity | FBC |

| Hypertension | U&E | |

| Gingival hypertrophy | LFT | |

| Lipid profile | ||

| Blood pressure | ||

| Urinalysis | ||

| Acitretin | Teratogenic (including up to 2 years post-treatment) | FBC |

| Dryness of mucous membranes and skin | U&E | |

| Hyperostoses, increased serum triglyceride | LFT | |

| Occasional hepatotoxic reaction | Lipid profile | |

| Fumaric Acid Esters | Gastro-intestinal side effects | FBC |

| Flushing | U&E | |

| Lymphopenia | LFT | |

| Proteinuria | Urinalysis | |

| Renal failure | ||

| Azathioprine | Myelosuppression | TPMT pre-treatment |

| Deranged liver function | FBC/U&E/LFT | |

| Gastro-intestinal effects |

U&Es, urea and electrolytes; LFTs, liver function tests; FBC, full blood count; TPMT, thiopurine methyl transferase genetic polymorphism screening.

Methotrexate

Patient monitoring in methotrexate therapy is detailed in Table 57.5. Liver function tests do not reliably predict hepatic fibrosis; supportive investigations are therefore required. Liver biopsy remains the gold standard. Recently, the measurement of serum pro-collagen three peptide levels has led to a reduction of liver biopsies for detection of hepatic fibrosis in these patients (Chalmers et al., 2005).

Biologic therapy

Biologic therapies or ‘biologics’ are drugs designed to block specific molecular steps important in immune-mediated disease. They have been used successfully in rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease and are now licensed for use in chronic plaque psoriasis. Their use is recommended for patients with severe plaque psoriasis defined as a PASI ≥ 10 and DLQI > 10 who have failed at least two standard systemic agents including methotrexate, ciclosporin and acitretin or one systemic agent and phototherapy (Smith et al., 2009).

The chronicity of this disease may lead to treatment ‘fatigue’ and frustration with messy topical therapies. There are numerous alternatives and newer formulations are generally less messy. Treatments can be expensive and information on the entitlement to benefits to replace clothing ruined by ointments or washing machines worn out by constant use is available. The Psoriasis Association (www.psoriasis-association.org.uk) provides an excellent service for this, together with practical advice from fellow sufferers about day-to-day problems.

Case 57.1

A 3-year-old child with known atopic eczema is seen in clinic with a widespread, excoriated, dry rash (see Fig. 57.15). Her eczema symptoms started at the age of 6 weeks. Her sleep has always been poor due to the marked itch symptoms at night. She has had two recent courses of oral antibiotics for presumed bacterial skin infection. Her normal skin treatment involves hydrocortisone 1% ointment to affected areas twice daily. Her parents are concerned regarding the possible triggers of her eczema flares and are keen to pursue possible allergy testing.

Answer

Fig. 57.15 shows a young child with moderate/severe atopic eczema. Ill-defined, dry, erythematous patches of eczema are visible. A few of the patches around her ankles appear crusty and eroded. This may represent secondary infection.

Case 57.4

A 9-year-old boy with known atopic eczema presented with a vesicular, blistering eruption over his face and trunk (see Fig. 57.16). His mother noticed the blisters 48 h ago and brought him to hospital as he was unwell and feverish. He had been using topical steroids and emollients regularly for his moderate atopic eczema. His sister has recently been suffering with cold sores.

Question

Fig. 57.16 shows the young patient with eczema herpeticum. What advice would you give this patient and his mother?

Answer

Eczema herpeticum, Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption, is an important and serious complication that can occur in eczema patients. This is a medical emergency and early treatment with aciclovir may prove lifesaving. This widespread eruption occurs following inoculation of herpes simplex virus to skin damaged by eczema. This then spreads rapidly and can affect the eyes and lungs. It usually manifests in young children with atopic eczema. Typically, the tiny blisters, vesicles, develop in large numbers on eczematous skin and patients are systemically unwell. The blisters or erosions appear ‘punched out’ and may be pustular. Eye involvement, as suggested in Fig. 57.16, necessitates urgent ophthalmological review as herpes simplex ocular infection can lead to corneal ulceration, stromal keratitis, iritis and permanent visual loss.

Case 57.5

A 33-year-old electrician presents to clinic with a 5-month history of a mildly itchy eruption occurring around the nasal area and eyebrows (see Fig. 57.17). He describes it as occasionally scaly and is very concerned regarding the cosmetic appearance. On examination, he also has mild scale and erythema affecting the scalp. The dandruff shampoos he usually purchases from his local community pharmacy have been ineffective. The diagnosis is seborrheic dermatitis.

Chalmers R.J., Kirby B., Smith A., et al. Replacement of routine liver biopsy by procollagen III aminopeptide for monitoring patients with psoriasis receiving long-term methotrexate: a multicentre audit and health economic analysis. Br. J. Dermatol.. 2005;152:444-450.

Gambichler T., Breuckmann F., Boms S., et al. Narrowband UVB phototherapy in skin conditions beyond psoriasis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol.. 2005;52:660-670.

Kapp A., Papp K., Bingham A., et al. Flare reduction in eczema with Elidel (infants) multicenter investigator study group. Long-term management of atopic dermatitis in infants with topical pimecrolimus, a non steroid anti-inflammatory drug. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol.. 2002;110:277-284.

Kirby B., Richards H.L., Mason D.L., et al. Alcohol consumption and psychological distress in patients with psoriasis. Br. J. Dermatol.. 2008;158:138-140.

Langley R.G., Eichenfield L.F., Lucky A.W., et al. Sustained efficacy and safety of pimecrolimus cream 1% when used long term (up to 26 weeks) to treat children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr. Dermatol.. 2008;25:301-307.

Meduri N.B., Vandergriff T., Rasmussen H., et al. Phototherapy in the management of atopic dermatitis: a systemic review. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed.. 2007;23:106-112.

Mehta N.N., Azfar R.S., Shin D.B., et al. Patients with severe psoriasis are at increased risk of cardiovascular mortality: cohort study using the General Practice Research Database. Eur. Heart J.. 2010;3:1000-1006.

MeReC. The use of emollients in dry skin conditions. MeReC Bull.. 1998;12:45-48.

Michaëlsson G., Gustafsson K., Hagforsen E. The psoriasis variant palmoplantar pustulosis can be improved after cessation of smoking. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol.. 2006;54(4):737-738.

Smith C.H., Anstey A.V., Barker J.N., et al. British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for biologic interventions for psoriasis. Br. J. Dermatol.. 2009;161:987-1019.

Weatherhead S.C., Wahie S., Reynolds N.J., et al. An open-label, dose-ranging study of methotrexate for moderate to severe adult atopic eczema. Br. J. Dermatol.. 2007;156:346-351.

Ashton R., Leppard B. Differential Diagnosis in Dermatology, third ed. Oxford: Radcliffe publishing limited; 2004.

Boyle R.J., Bath-Hextall F.J., Leonardi-Bee J., et al. Probiotics for treating eczema. Cochrane Database Sys. Rev.. (4):2008. Art No. CD006135. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006135.pub2

Brown S., Reynolds N.J. Atopic and non-atopic eczema. Br. Med. J.. 2006;332:584-588.

Buxton P. ABC of Dermatology, fourth ed. London: BMJ Books; 2003.

Ghaffar S.A., Clements S.E., Griffiths C.E. Modern management of psoriasis. Clin. Med.. 2005;5:564-568.

Hui R.L., Lide W., Chan J., et al. Association between exposure to topical tacrolimus or pimecrolimus and cancers. Ann. Pharmacother.. 2009;43:956-963.

Menter A., Griffiths C.E. Current and future management of psoriasis. Lancet. 2007;370:272-284.

Williams H.C.,. Atopic Dermatitis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.