Chapter 296 Echinococcosis (Echinococcus granulosus and Echinococcus multilocularis)

Etiology

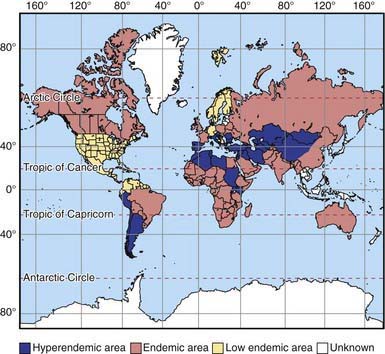

Echinococcosis (hydatid disease or hydatidosis) is the most widespread, serious human cestode infection in the world (Fig. 296-1). Two major Echinococcus species are responsible for distinct clinical presentations, E. granulosus (cystic hydatid disease) and the more malignant E. multilocularis (alveolar hydatid disease). The adult parasite is a small (2-7 mm) tapeworm with only 2-6 segments that inhabits the intestines of dogs, wolves, dingoes, jackals, coyotes, and foxes. These carnivores pass the eggs in their stool, which contaminates the soil, pasture, and water, as well as their own fur. Domestic animals such as sheep, goats, cattle, and camels ingest E. granulosus eggs while grazing. Humans are also infected by consuming food or water contaminated with eggs or by direct contact with infected dogs. The larvae hatch, penetrate the gut, and are carried by the vascular or lymphatic systems to the liver, lungs, and less commonly bones, brain, or heart.

Diagnosis

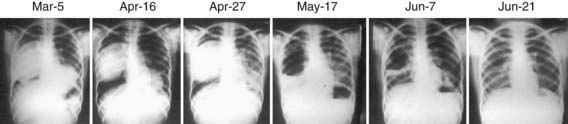

Subcutaneous nodules, hepatomegaly, or a palpable abdominal mass may be found. The parasite cannot be recovered from any easily accessible body fluid unless a lung cyst ruptures, after which protoscolices or layers of cyst wall may briefly be seen in sputum. Ultrasonography is the most valuable tool for both the diagnosis and treatment of cystic hydatid disease of the liver. The presence of internal membranes and falling echogenic cyst material (hydatid sand) observed in real time aid in the diagnosis. Alveolar disease is less cystic in appearance and resembles a diffuse solid tumor. CT findings (Fig. 296-2) are similar to those of ultrasonography and may at times be useful in distinguishing alveolar from cystic hydatid disease in geographic regions where both occur. CT or MRI is also important in planning a surgical intervention. Lung hydatid is usually apparent on chest x-ray (Fig. 296-3).

Buishi I, Walters T, Guildea Z, et al. Reemergence of canine Echinococcus granulosus infection, Wales. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:568-571.

Eckert J, Deplazes P. Biological, epidemiological, and clinical aspects of echinococcosis, a zoonosis of increasing concern. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:107-135.

McManus DP, Zhang W, Li J, et al. Echinococcosis. Lancet. 2003;362:1295-1304.

Moro PL, Schantz PM. Echinococcosis: historical landmarks and progress in research and control. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2006;100:703-714.

Nasseri Moghaddam S, Abrishami A, et al: Percutaneous needle aspiration, injection, and reaspiration with or without benzimidazole coverage for uncomplicated hepatic hydatid cysts, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 19:CD003623, 2006.