23 EC-IC Bypass for Giant ICA Aneurysms

Introduction

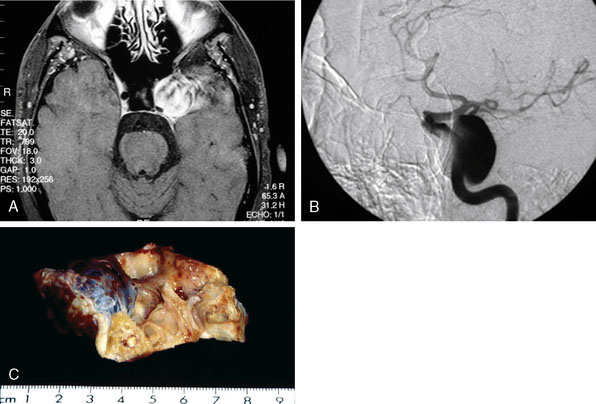

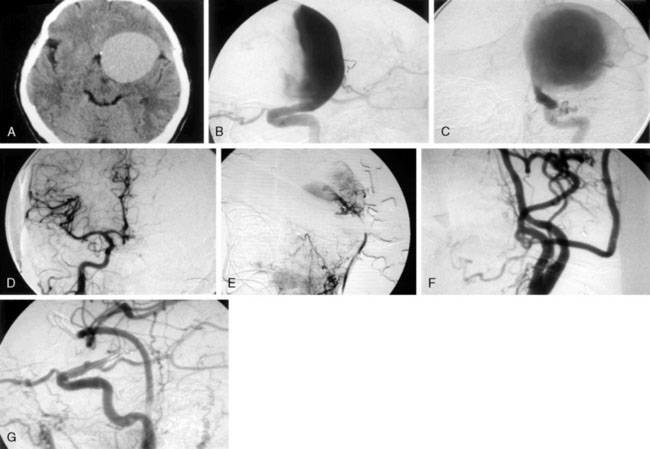

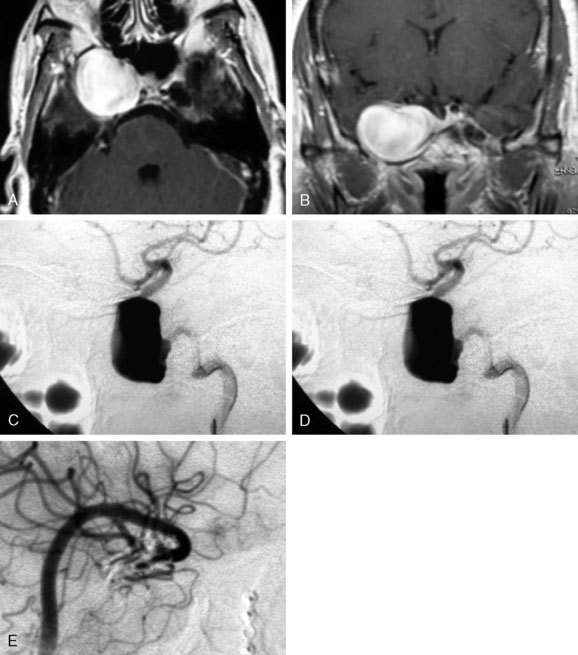

Pure cavernous ICA aneurysms are a separate category of aneurysms, which do not extend beyond the dural ring of the ICA. In general, in the neurosurgical literature these aneurysms are considered benign, even in larger sizes.1 However, in our experience it is possible that when these aneurysms get significantly large in size, they can cause rupture through the middle fossa dura, causing hemorrhage and potential mortality (Figure 23–1).

Natural history of transitional segment of ICA aneurysms

Unruptured intracranial aneurysms are being diagnosed more often than in the past and these lesions pose management problems. The first series of giant aneurysms was presented in 1969 by Morley and Barr, who described giant aneurysms as >2.5 cm.2 Giant aneurysms are relatively rare, comprising between 5% and 7% of aneurysms3 in most series. Giant aneurysms have a female predominance with ratios as high as 3:1 in some series4 and most commonly present in the middle decades. Giant aneurysms are most frequently located on the ICA, specifically, involving the paraclinoid segment 21% of the time.5

The natural history of giant aneurysms is one of a poor prognosis. Some have compared the fate of unruptured giant aneurysms to that of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH).6 Patients often present with symptoms consistent with SAH or mass effect. The Italian cooperative study has shown a 28% mortality rate for untreated giant aneurysms compared to a 14% mortality rate for patients who received treatment.7 In the same series, morbidity was seen in 48% of cases due to expansion. Giant aneurysms, not unlike other aneurysms, continue to enlarge over time. Expansion is thought to be from growth of the lumen or thrombus formation within the sac. This progressive enlargement often causes symptoms of mass effect.8

Historically, it was thought that giant aneurysms were less prone to rupture; however, contemporary evidence suggests that this is inaccurate. Drake found that 62 of 174 cases did rupture.9 Aneurysms sized ≥25 mm had a relative risk of rupture of 59% compared to aneurysms <10 mm.10 Giant aneurysms had a 6% rupture rate in the first year compared to <1% for aneurysms <10 mm.10 Patients with a giant aneurysm, but without previous SAH, were at a significantly increased risk for rupture based on size. The rupture rate was not dependent on the location of the aneurysm; all anterior circulation giant aneurysms were at increased risk of rupture.3 Risk factors for aneurysm rupture include hypertension, current or former tobacco use, alcohol use greater than five drinks per day, and use of oral contraceptives.10 It was thought that partially or completely thrombosed aneurysms would be less likely to rupture, thus not requiring treatment; however, in Drake’s large series, this was not the case.9

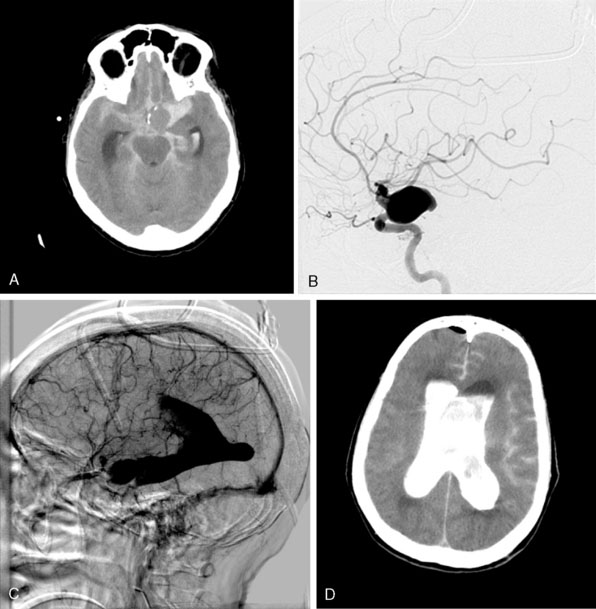

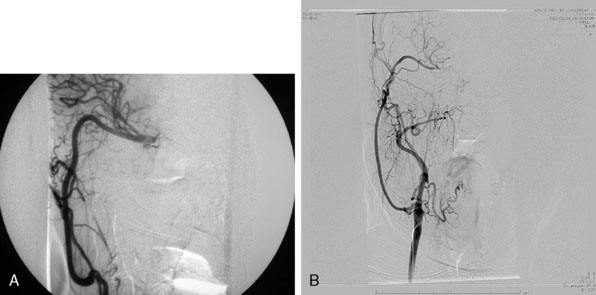

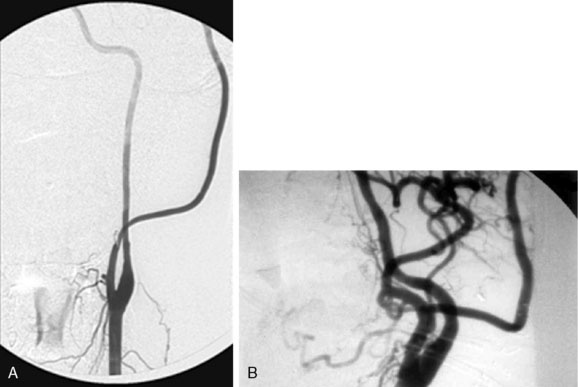

The ISUIA (International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms Investigators) trial has shown that un-ruptured aneurysms overall do not pose the risk they once were thought to; and that treating aneurysms, specifically small ones, puts the patient at more risk than surveillance. However, this advice should not be applied to the special case of giant aneurysms, where “the natural history is ominous.”6 Morley and Barr’s original series demonstrated similar findings, with an 80% mortality rate for untreated aneurysms. Other studies have shown high 1-year mortality rates.11 Peerless et al. found that 85% of patients with giant intracranial aneurysms were dead at 5 years.12 Additionally, the ISUIA II found that the cumulative rupture rates for anterior circulation giant aneurysms with no previous history of SAH were 40%. Patients who present with SAH are at increased risk of mortality compared to patients without SAH.13 We present a case of a ruptured giant aneurysm without previous history of SAH 6 months after initial diagnosis (Figure 23–2).

The Dilemma of Deliberate ICA Occlusion

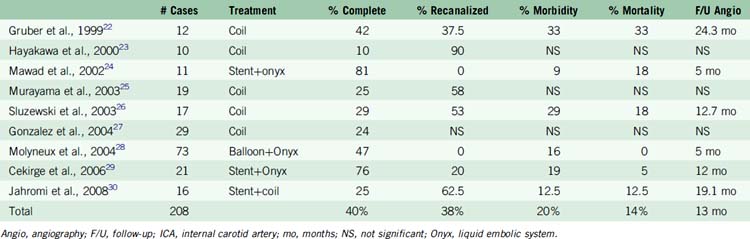

Traditional neurosurgical literature and practice have held a liberal view of ICA occlusion for the treatment of giant ICA aneurysms. Historically, this has been accompanied by a relatively high risk of stroke following the ICA occlusion (Table 23–1). With recent improvements in the balloon test occlusion (BTO) paradigms, the risk is smaller but clearly not absent.

| Source | Surgery | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Sahs and Locksley, 196914 | ICA ligation | Stroke 30% Mortality 20.7% |

| Roski et al., 198115 | ICA ligation | TIA 16.6% Stroke 16.6% SAH 5.5% Mortality 5.5% |

| Linskey et al., 199416 | Intravascular ICA occlusion | Stroke 12.9% Mortality 3.2% |

| Larson et al., 199517 | Intravascular ICA occlusion | TIA 10.9% Stroke 3.6% SAH 3.6% Mortality 5.4% |

ICA, internal carotid artery; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

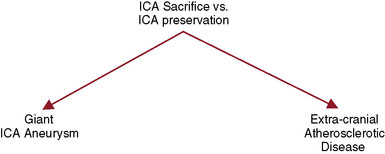

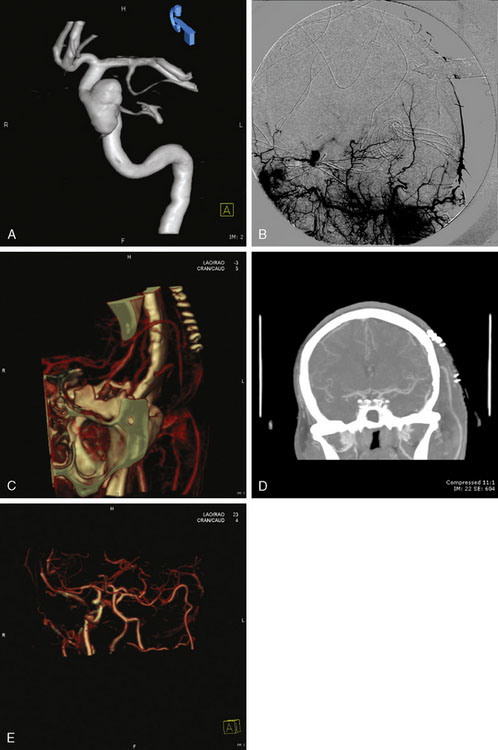

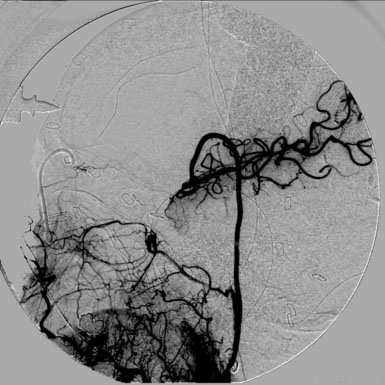

For the treatment of carotid occlusive disease, traditional neurosurgical literature and practice have strongly recommended preservation of the ICA. High-grade stenosis (i.e., 99% stenosis) is considered a relative neurosurgical emergency, requiring an endarterectomy or stenting. It is interesting that most patients who present with cervical carotid occlusive disease are usually older and generally have multiple medical comorbidities; yet performing a procedure to open the carotid artery has remained standard practice. Most cervical carotid occlusive disease symptomatology is due to embolic disease rather than hemodynamic compromise. Therefore, in the majority of cervical carotid occlusive disease, a deliberate occlusion of the ICA, in the opinion of the senior author, could be performed with a relatively low risk of morbidity, and most likely less risk of morbidity and mortality, when compared to carotid endarterectomy or stenting. However, this would be considered a complete departure from our current standards of care (Figure 23–3).

Experience at St. Louis University Hospital in Treatment of Giant ICA Aneurysms

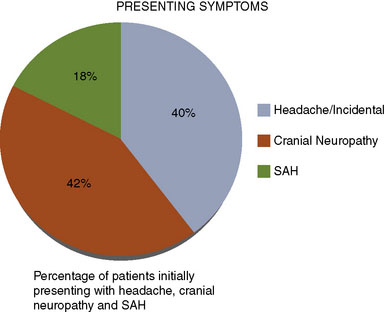

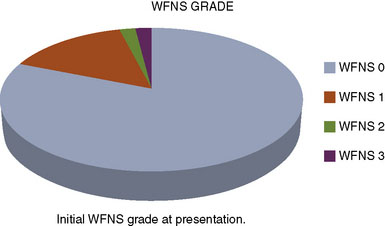

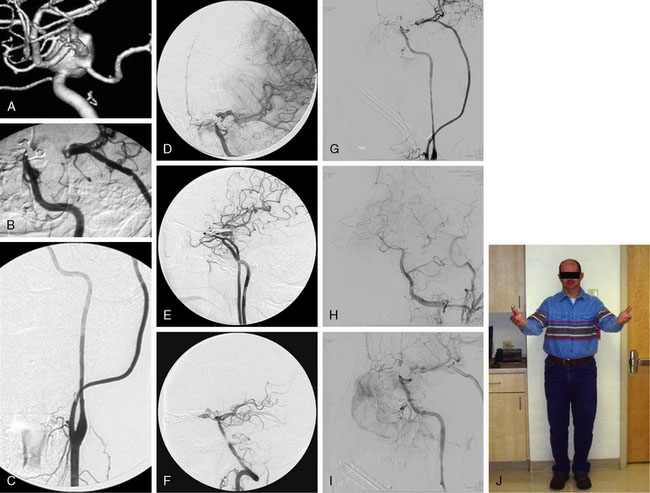

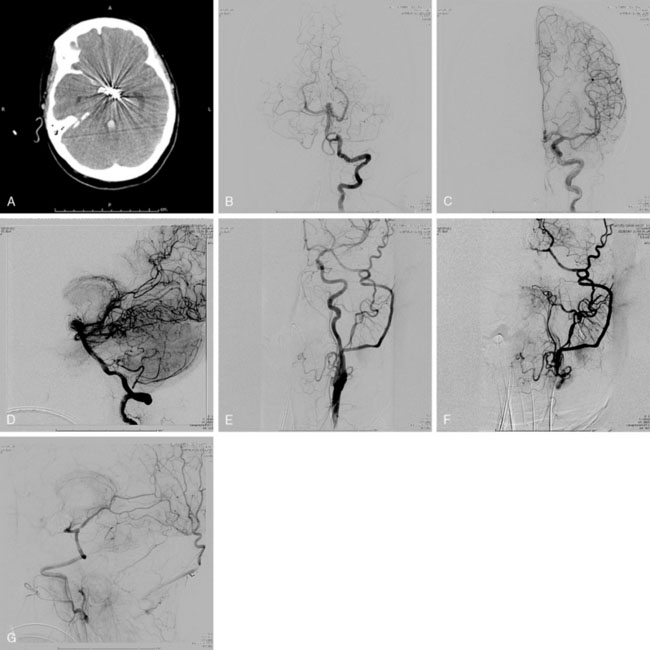

We performed a retrospective review of 55 consecutive patients treated at St. Louis University Hospital from June 1999 to June 2007. All 55 patients had transitional ICA aneurysms. The mean aneurysm size was 34.7 mm (range 25 to 70 mm). The mean age was 46 years (range 30 to 64 years). The mean follow-up period was 34.7 months (range 1 to 76 months). The objectives of this study were to assess the use of high-flow EC-IC bypass for the treatment of giant transitional ICA aneurysms, delineate surgical mortality and morbidity, and determine the long-term efficacy of the treatment and functional outcomes of these patients. The presenting symptoms were cranial neuropathy (42%), headache or incidental finding (40%), and SAH (18%) (Figure 23–4). The World Federation of Neurological Surgeons (WFNS) grade was 0 in 81%, 1 in 15%, 2 in 2%, and 3 in 2% (Figure 23–5). All 55 patients underwent a high-flow EC-IC bypass procedure.

Surgical technique

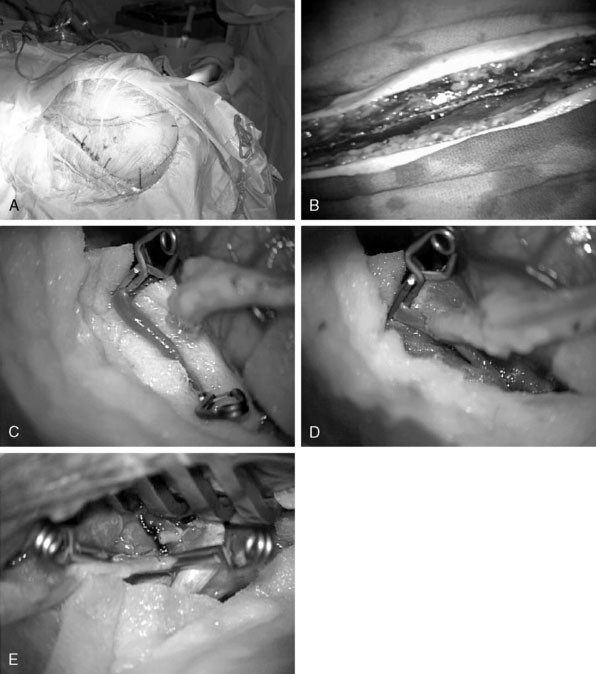

Craniotomy: A skull base approach, usually a cranio-orbital or a cranio-orbital-zygomatic access, is usually needed. We prefer a single-piece craniotomy, which entails an osteotomy of the orbital roof and lateral margins. A high-speed drill is used to thin the zygomatic arch posteriorly, which allows the radial artery to lie without kinking at the zygomatic area (Figure 23–6A).

Radial artery harvest: The critical aspect of radial artery harvest is the length of the graft, which can be limiting. Obtaining maximal length is critical during this harvest. The senior author prefers to personally mark the superficial wall of the radial artery with a marking pen prior to removal of the graft. This step is crucial to avoid rotation during the tunneling (Figure 23–6B). Once the graft is harvested, it is placed in a heparinized saline solution.

Intracranial anastomosis: We also start the patient on aspirin (81 mg) daily for 3 days prior to surgery. Intraoperative continuous electroencephalography (EEG), somatosensory-evoked potential (SSEP), and motor-evoked potentials are monitored. The site of the anastomosis is determined based on several factors: intended revascularization territory, size of donor and recipient vessels, length of the graft, and location of the aneurysm. Mild hypothermia is used. EEG burst suppression using pentobarbital is maintained during the temporary clipping period. A color background is placed behind the recipient vessel. Temporary clips are applied (Figure 23–6C). An arteriotomy is made using an arachnoid knife. The arteriotomy is extended using a microscissors to the width of the donor vessel lumen. The lumen of the donor vessel is expanded by “fish-mouthing” the opening. We used 9-0 nylon for M2 and M3 vessels and 8-0 nylon for the supraclinoidal ICA. We prefer a running suture technique and performing the “back” wall (i.e., the more difficult anastomosis) first, followed by the front wall (Figure 23–6D). When the anastomosis is completed, retrograde flow is confirmed in the graft followed by positioning of a temporary clip on the graft just distal to the anastomosis.

Cervical carotid anastomosis: The graft length is cut to expose an area of the ECA where the proximal anastomosis is planned. Yasargil long temporary clips can be used for the ECA anastomosis. Similar technique of “back” wall and “front” wall can be utilized as described previously for the intracranial anastomosis. For this part, 7-0 prolene can be used (Figure 23–6E).

Parent vessel occlusion: Once the preceding steps, including intraoperative angiography, have documented flow in the graft, we then advocate parent vessel occlusion during the same surgical procedure, rather than delayed (staged) occlusion. In our opinion, the risk of graft occlusion would be high if competitive flow in the parent vessel were allowed to continue. We occlude the ICA at the level of the bifurcation in the cervical area and just distal to the giant aneurysm in the supra-clinoidal portion of the ICA. The distal occlusion must be performed proximal to the anterior choroidal and dominant posterior communicating arteries.18

Results of Giant Aneurysm Series

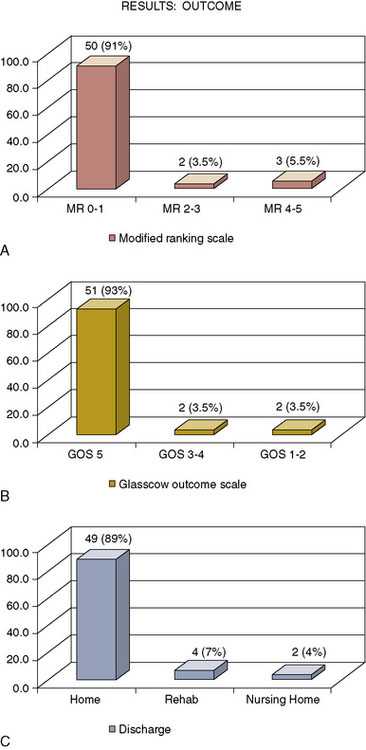

The outcome of this series shows that 50 patients (91%) had a Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) of 0 to 1, two patients (3.5%) had a mRS of 2 to 3, and three patients (5.5%) had a mRS of 4 to 5. Fifty-one patients (93%) had a Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) of 5, two patients (3.5%) had a GOS of 3 to 4, and two (3.5%), a GOS of 1 to 2. At discharge from the hospital, 49 (89%) of the patients went home, four (7%) went to rehabilitation facilities, and two patients (4%) went to nursing homes (Figure 23–7).

Acute graft occlusion occurred in four patients (7.3%), and late graft occlusion in four (7.3%). The main complication/morbidity was reflected in our cerebrovascular accident (CVA) rate, which occurred in four patients (7.3%). Two patients had CVA secondary to acute graft occlusion, and two had CVA secondary to microsurgical manipulation of calcified aneurysms. Aneurysm recurrence was seen in only one patient (Figure 23–8). Mortality occurred in one patient from a pulmonary embolus at home 5 weeks postoperatively.

Options for treatment of giant ica aneurysms

Traditional treatment of giant aneurysms was direct microsurgical clipping. This continues to be a feasible option in certain cases. However, the risk of direct clipping of giant aneurysms is not low. Our review of major series of direct clipping of giant ICA aneurysms revealed a fair to poor outcome in approximately 18% of the patients. In these same series, the mortality rate was 11% (Table 23–2). Endovascular treatment of giant aneurysms also poses certain challenges. In our review of major series of coiling, stent plus coiling of giant aneurysms reveals that approximately 42% of the aneurysms are completely occluded by the treatment. Thirty-seven percent of the aneurysms recanalize. Major morbidity occurred in approximately 21% of the patients. Mortality occurred in 15% of the patients (Table 23–3).

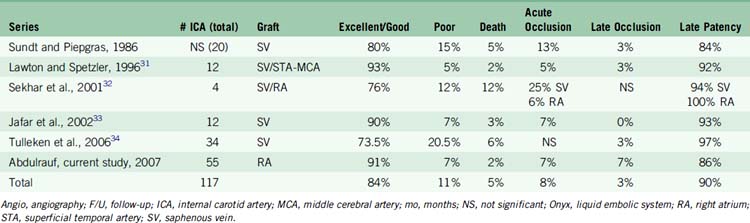

EC-IC bypass for giant aneurysms in the major published series shows relatively better outcomes than direct microsurgical clipping or endovascular treatment. Based on our review of these major series, excellent to good outcome was achieved on average in 84% of the patients. Significant morbidity was seen on average in 11% of the patients. Mortality was seen on average in 5% of the patients (Table 23–4).

Technical nuances in high-flow ec-ic bypass surgery

Importance of Atypical Appearance of Giant Aneurysms

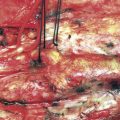

Irregular appearance of the wall, or the pattern of more than one sac, indicates partial calcification or thrombosis. The appearance of the aneurysm on cerebral angiography is a critical factor in decision making regarding treatment. In the experience of the senior author, complex aneurysms, including those with irregular appearance of the wall, outpouching within the dome, or the presence of calcification, may carry a higher risk with direct clipping. Partial thrombosis of the aneurysm may show a smaller aneurysm on angiography when compared to the MRI. Partially thrombosed aneurysms also carry a risk of embolic complications during microsurgical clipping or endovascular coiling (Figure 23–9).

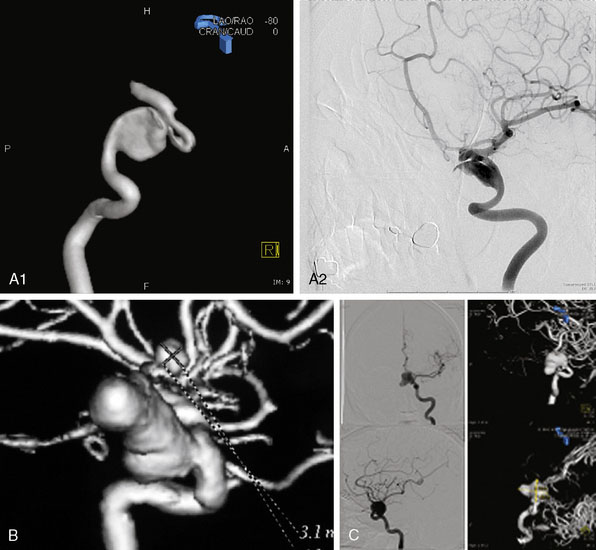

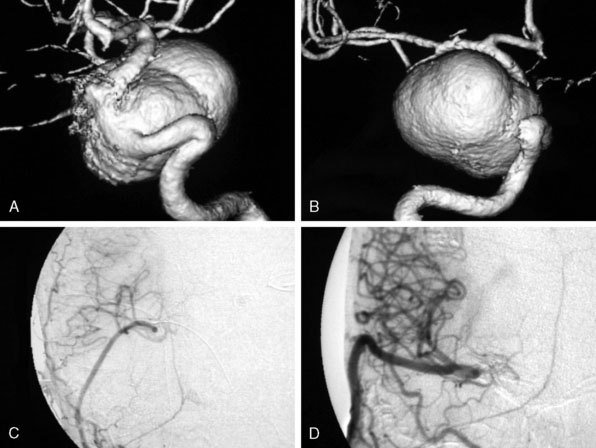

Aneurysm size: The size of the aneurysm, although a critical factor when considering direct microsurgical clipping or endovascular coiling, is not an equally important factor when considering EC-IC bypass. In our opinion, for significantly large aneurysms, EC-IC bypass would be the least risky procedure (Figure 23–10).

EC-IC bypass for giant cavernous segment ICA aneurysm: The location of the aneurysm is an important factor when making decisions regarding treatment. Endovascular stenting plus coiling or EC-IC bypass are potential treatments of a giant cavernous segment aneurysm. Direct surgical clipping should not be considered in these cases, as it would almost certainly lead to ophthalmoplegia (Figure 23–11).

End-to-side versus end-to-end proximal anastomosis: For the proximal anastomosis, both end-to-end or end-to-side are options. The senior author prefers the use of the ECA as the donor vessel. This avoids temporary occlusion of the ICA during the procedure. The advantage of end-to-end anastomosis is, presumably, more vigorous flow into the graft. The disadvantage of end-to-end anastomosis is potential occlusion of ophthalmic-based collaterals into the surpraclinoidal carotid artery. End-to-side anastomosis, therefore, is a reasonable option, and it is an easier anastomosis to make in comparison to end-to-end (end-to-end may create a size mismatch that may in certain occasions be difficult to compensate for) (Figure 23–12).

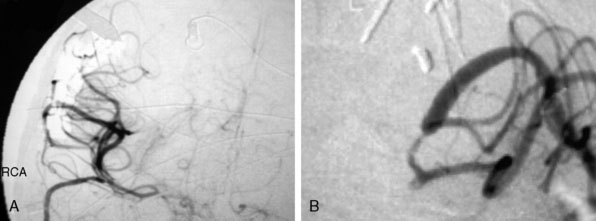

Figure 23–12 A, End-to-side radial artery graft to the ECA. B, End-to-end radial artery graft to the ECA.

Competitive flow: It is important to recognize that during intraoperative angiography, the graft may only supply a single division of the recipient territory (i.e., a single M2 division). This should not be a concerning sign. In general, this is due to the fact that there is significant competitive flow coming through the ACA from the contralateral side, which is protective, and the surgeon should not change the strategy during the case (Figure 23–13).

Figure 23–13 Intraoperative angiogram of an ECA to MCA radial artery bypass showing flow into a single MCA division.

Radial artery graft enlargement over time as graft adapts to blood flow demands: The diameter size of the graft as seen during intraoperative catheter or ICG is not concerning as long as there is no occlusion or specific area of stenosis. In our experience, the graft will expand in diameter over time to accommodate for blood flow demand (Figure 23–14).

Intraoperative failure of graft: In most situations where the graft is not visible during intraoperative angiography, technical failure is assumed, and the anastomosis, as well as the tunneling, should be reinvestigated. In patients who have passed the BTO, it is possible to have such significant competitive flow that the resistance in the graft cannot match the higher contralateral flow and the graft is not necessary. It is important to look at every step of the procedure to ensure that there is no technical failure before making any other decisions. If no technical failures are found and no changes in the patient’s motor and sensory evoked potentials are detected, it is reasonable to leave the graft in place. In certain circumstances, the graft may enlarge over time if demand is placed on it. While in other situations, the graft would be occluded without any neurological symptoms based on the fact that competitive flow was significantly strong and the graft was not needed to start with (Figure 23–15).

Creation of a new posterior communicating artery: EC-IC bypass surgery is an intellectual exercise given the complexity of the aneurysm. In certain situations, an intraposition graft may be needed. In some cases, an IC-IC bypass may be more appropriate than an EC-IC bypass. In other cases, the creation of a new ACA or PCA (using an interposition graft) may aid in the treatment of the specific aneurysm, whether it is microsurgical or endovascular (Figure 23–16).

Length of the graft and risk of occlusion: The length of the graft is also an important aspect. Unneeded length may lead to kinking in the cervical or cranial areas and could be a risk factor for graft occlusion. This aspect has to be well studied during the operation, as this is an important variable in achieving success in EC-IC bypass surgery (Figure 23–17).

Distal anastomosis size mismatch: From a technical standpoint of the distal anastomosis, it is important to match the size of the donor and recipient arteries. In our opinion a significant size mismatch could have a higher risk of turbulent flow and subsequent thrombosis at the anastomosis site (Figure 23–18).

1 Linskey M.E., et al. Aneurysms of the intracavernous carotid artery: natural history and indications for treatment. Neurosurgery. 1990;26(6):933-937. discussion, 937–938

2 Morley T.P., Barr H.W. Giant intracranial aneurysms: diagnosis, course, and management. Clin Neurosurg. 1969;16:73-94.

3 Wiebers D.O., et al. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: natural history, clinical outcome, and risks of surgical and endovascular treatment. Lancet. 2003;362:103-110.

4 Whittle I.R., Dorsch N.W., Besser M. Giant intracranial aneurysms: diagnosis, management, and outcome. Surg Neurol. 1984;21:218-230.

5 Nukui H., et al. [Bilaterally symmetrical giant aneurysms of the internal carotid artery within the cavernous sinus, associated with an aneurysm of the basilar artery [author’s transl.]. No Shinkei Geka. 1977;5:479-484.

6 Awad I.A., Barrow D.L., editors. Giant Intracranial Aneurysms. Park Ridge, IL: American Association of Neurological Surgeons, 1995.

7 Pasqualin A., et al. Italian cooperative study on giant intracranial aneurysms: 4. Results of treatment. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien). 1988;42:65-70.

8 Sonntag V.K., Yuan R.H., Stein B.M. Giant intracranial aneurysms: a review of 13 cases. Surg Neurol. 1977;8(2):81-84.

9 Drake C.G. Giant intracranial aneurysms: experience with surgical treatment in 174 patients. Clin Neurosurg. 1979;26:12-95.

10 International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms Investigators. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms—risk of rupture and risks of surgical intervention. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1725-1733.

11 Heros R.C., Kistler J.P. Intracranial arterial aneurysm—an update. Stroke. 1983;14:628-631.

12 Peerless S.J., Wallace M.D., Drake C.G. Giant intracranial aneurysms. In: Youmans J.R., editor. Neurological Surgery. ed 3. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1990:1742-1763.

13 Hamburger C., Schonberger J., Lange M. Management and prognosis of intracranial giant aneurysms. A report on 58 cases. Neurosurg Rev. 1992;15(2):97-103.

14 Locksley S.A. Intracranial aneurysms and subarachnoid hemorrhage: a cooperative study. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1969.

15 Roski R.A., Spetzler R.F., Nulsen F.E. Late complications of carotid ligation in the treatment of intracranial aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1981;54(5):583-587.

16 Linskey M.E., et al. Stroke risk after abrupt internal carotid artery sacrifice: accuracy of preoperative assessment with balloon test occlusion and stable xenon-enhanced CT. Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15(5):829-843.

17 Larson J.J., et al. Treatment of aneurysms of the internal carotid artery by intravascular balloon occlusion: long-term follow-up of 58 patients. Neurosurgery. 1995;36(1):26-30. discussion 30

18 Abdulrauf S.I. Extracranial-to-intracranial bypass using radial artery grafting for complex skull base tumors: technical note. Skull Base. 2005;15:207-213.

19 Sundt T.M.Jr, Piepgras D.G. Surgical approach to giant intracranial aneurysms: operative experience with 80 cases. J Neurosurg. 1979;51(6):731-742.

20 Symon L., Vajda J. Surgical experiences with giant intracranial aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1984;61(6):1009-1028.

21 Batjer H.H., Kopitnik T.A., Giller C.A., et al. Surgery for paraclinoidal carotid artery aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1994;80(4):650-658.

22 Gruber A., et al. Clinical and angiographic results of endosaccular coiling treatment of giant and very large intracranial aneurysms: a 7-year, single-center experience. Neurosurgery. 1999;45(4):793-803. discussion 803–804

23 Hayakawa M., et al. Natural history of the neck remnant of a cerebral aneurysm treated with the Guglielmi detachable coil system. J Neurosurg. 2000;93(4):561-568.

24 Mawad M.E., et al. Endovascular treatment of giant and large intracranial aneurysms by using a combination of stent placement and liquid polymer injection. J Neurosurg. 2002;96(3):474-482.

25 Murayama Y., et al. Guglielmi detachable coil embolization of cerebral aneurysms: 11 years’ experience. J Neurosurg. 2003;98(5):959-966.

26 Sluzewski M., et al. Coiling of very large or giant cerebral aneurysms: long-term clinical and serial angiographic results. Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24(2):257-262.

27 Gonzalez L.F., Zabramski J.M. Anatomic and clinical study of the orbitopterional approach to anterior communicating artery aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 2004;54(4):1031-1032.

28 Molyneux A.J., et al. Cerebral Aneurysm Multicenter European Onyx (CAMEO) trial: results of a prospective observational study in 20 European centers. Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25(1):39-51.

29 Cekirge H.S., et al. Intrasaccular combination of metallic coils and onyx liquid embolic agent for the endovascular treatment of cerebral aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 2006;105(5):706-712.

30 Jahromi B.S., et al. Clinical and angiographic outcome after endovascular management of giant intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 2008;63(4):662-674. discussion 674–675

31 Lawton M.T., Hamilton M.G., Morcos J.J., et al. Revascularization and aneurysm surgery: current techniques, indications, and outcome. Neurosurgery. 1996;38(1):83-92. discussion 92–94

32 Sekhar L., Duff J.M., Kalavakonda C., et al. Cerebral revascularization using radial artery grafts for the treatment of complex intracranial aneurysms: techniques and outcomes for 17 patients. Neurosurgery. 2001;49(3):646-658.

33 Jafar J.J., Russell S.M., Woo H.H. Treatment of giant intracranial aneurysms with saphenous vein extracranial-to-intracranial bypass grafting: indications, operative technique, and results in 29 patients. Neurosurgery. 2002;51(1):138-144. discussion 144–146

34 Tulleken C.A., et al. Treatment of giant and large internal carotid artery aneurysms with a high-flow replacement bypass using the excimer laser-assisted nonocclusive anastomosis technique. Neurosurgery. 2006;59(4 Suppl 2):ONS328-ONS334. discussion ONS334–ONS335