Chapter 26 Eating Disorders

Definitions

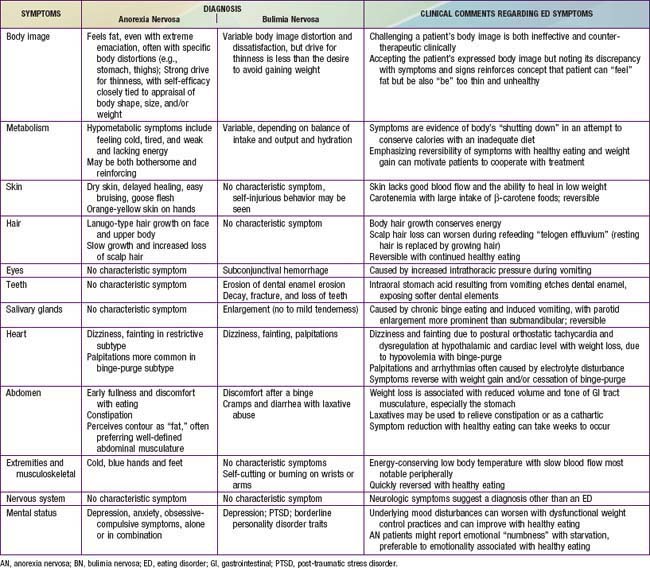

Anorexia nervosa (AN) involves significant overestimation of body size and shape, with a relentless pursuit of thinness that typically combines excessive dieting and compulsive exercising in the restrictive subtype; in the binge-purge subtype, patients might intermittently overeat and then attempt to rid themselves of calories by vomiting or taking laxatives, still with a strong drive for thinness (Table 26-1). Bulimia nervosa (BN) is characterized by episodes of eating large amounts of food in a brief period, followed by compensatory vomiting, laxative use, and exercise or fasting to rid the body of the effects of overeating in an effort to avoid obesity (Table 26-2).

Table 26-1 DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR 307.1 ANOREXIA NERVOSA

Specify Type:

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, ed 4, Washington, DC, 1994, American Psychiatric Association.

Table 26-2 DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR 307.51 BULIMIA NERVOSA

Specify Type:

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, ed 4, Washington, DC, 1994, American Psychiatric Association.

The majority of children and adolescents with EDs do not fulfill all of the criteria for either of these syndromes in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) classification system but fall instead into the category of eating disorder, not otherwise specified (ED-NOS) (Table 26-3). ED-NOS includes a wide variety of subthreshold clinical presentations. Binge eating disorder (BED), in which binge eating is not followed regularly by any compensatory behaviors, is included in ED-NOS in DSM-IV and shares many features with obesity (Chapter 44). ED-NOS, often called “disordered eating,” can worsen into full syndrome EDs.

Table 26-3 307.50 EATING DISORDER NOT OTHERWISE SPECIFIED

The Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified category is for disorders of eating that do not meet the criteria for any specific Eating Disorder. Examples include:

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, ed 4, Washington, DC, 1994, American Psychiatric Association.

Epidemiology

Family influence in the development of EDs is even more complex because of the interplay of environmental and genetic factors; shared elements of the family environment and immutable genetic factors account for significant (about equal) variance in disordered eating. There are associations between parents’ and children’s eating behaviors; dieting and physical activity levels suggest parental reinforcement of body-related societal messages. The influence of inherited genetic factors on the emergence of EDs during adolescence is also significant, but not in a direct fashion. Rather, the risk for developing an ED appears to be mediated through a genetic predisposition to anxiety (Chapter 23), depression (Chapter 24), or obsessive-compulsive traits that may be modulated through the internal milieu of puberty. There is little evidence that parents “cause” an ED in their child or adolescent; the importance of parents in treatment and recovery cannot be overestimated.

Clinical Manifestations

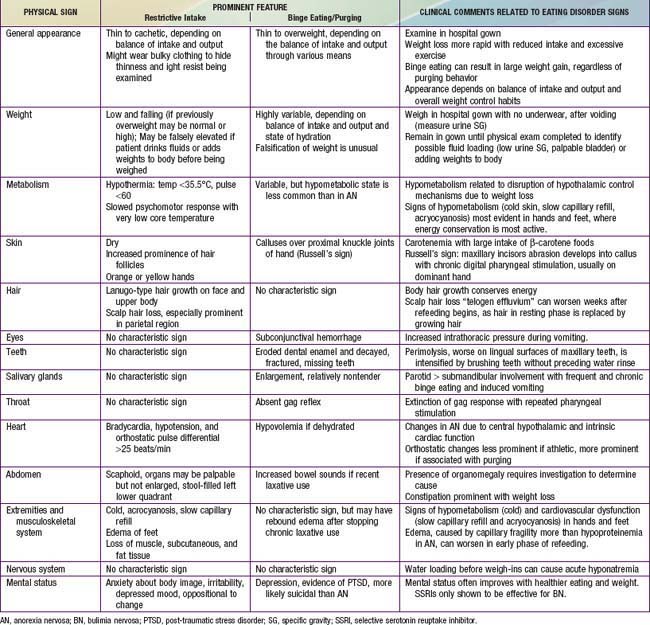

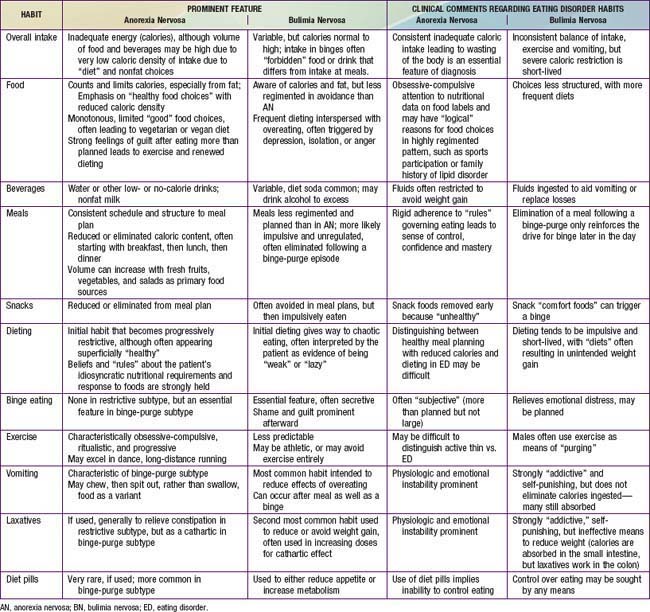

A central feature of EDs is the overestimation of body size, shape or parts (e.g., abdomen, thighs) leading to weight-control practices intended to reduce weight (AN) or prevent weight gain (BN). Associated practices include severe restriction of caloric intake and behaviors intended to reduce the effect of calories ingested, such as compulsive exercising or purging by inducing vomiting or taking laxatives. Eating and weight loss habits commonly found in EDs can result in a wide range of energy intake and output, the balance of which leads to a wide range in weight from extreme loss of weight in AN to fluctuation around a normal to moderately high weight in BN. Reported eating and weight-control habits (Table 26-4) thus inform the initial primary care approach.

Table 26-4 EATING AND WEIGHT CONTROL HABITS COMMONLY FOUND IN CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS WITH AN EATING DISORDER

Although weight-control patterns guide the initial pediatric approach, an assessment of commonly reported symptoms and findings on physical examination is essential to identify targets for intervention. When reported symptoms of excessive weight loss (feeling tired and cold; lacking energy; orthostasis; difficulty concentrating) are explicitly linked by the clinician to their associated physical signs (hypothermia with acrocyanosis and slow capillary refill, loss of muscle mass, bradycardia with orthostasis), it becomes more difficult for the patient to deny that a problem exists. Furthermore, awareness that bothersome symptoms can be eliminated by healthier eating and activity patterns can increase a patient’s motivation to engage in treatment. Tables 26-5 and 26-6 detail common symptoms and signs that should be addressed in a pediatric assessment of a suspected ED.

Treatment

Nutrition and Physical Activity

A standard nutritional balance of 15-20% calories from protein, 50-55% from carbohydrate, and 25-30% from fat is appropriate. The fat content may need to be lowered to 15-20% early in the treatment of AN because of continued fat phobia. With the risk of low BMD in patients with AN, calcium and vitamin D supplements are often needed to attain the recommended 1300 mg/day intake of calcium. Refeeding can be accomplished with frequent small meals and snacks consisting of a variety of foods and beverages (with minimal diet or fat-free products), rather than fewer high-volume high-calorie meals. Some patients find it easier to take in part of the additional nutrition as canned supplements (medicine) rather than food. Regardless of the source of energy intake, the risk for refeeding syndrome (acute tachycardia and heart failure with neurologic symptoms associated primarily with acute decline in serum phosphate and magnesium) increases with the degree of weight loss and the rapidity of caloric increases. Therefore, if the weight has fallen below 80% of expected weight for height, refeeding should proceed cautiously, possibly in the hospital (Table 26-7).

Table 26-7 INDICATIONS FOR IN-PATIENT MEDICAL HOSPITALIZATION OF PATIENTS WITH ANOREXIA NERVOSA

PHYSICAL AND LABORATORY

PSYCHIATRIC

MISCELLANEOUS

Referral to an Interdisciplinary Eating Disorder Team

Inpatient medical treatment of EDs is generally limited to patients with AN, to stabilize and treat life-threatening starvation and to provide supportive mental health services. Inpatient medical care may be required to avoid refeeding syndrome in severely malnourished patients, provide nasogastric tube feeding for patients unable or unwilling to eat, or initiate mental health services, especially family-based treatment, if this has not occurred on an outpatient basis (see Table 26-7). Admission to a general pediatric or hospital unit is advised only for short-term stabilization in preparation for transfer to a medical unit with expertise in treating pediatric EDs. Inpatient psychiatric care of EDs should be provided on a unit with expertise in managing the often challenging behaviors (e.g., hiding or discarding food, vomiting, surreptitious exercise) and emotional problems (e.g., depression, anxiety). Suicidal risk is small, but patients with AN might threaten suicide if made to eat or gain weight in an effort to get their parents to back off.

Supportive Care

In relation to pediatric EDs, support groups are primarily designed for parents. Because their daughter or son with an ED often resists the diagnosis and treatment, parents often feel helpless and hopeless. Because of the historical precedent of blaming parents for causing EDs, parents often express feelings of shame and isolation (www.maudsleyparents.org). Support groups and multifamily therapy sessions bring parents together with other parents whose families are at various stages of recovery from an ED in ways that are educational and encouraging. Patients often benefit from support groups after intensive treatment or at the end of treatment because of residual body image or other issues after eating and weight have normalized.

American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with eating disorders, ed 3. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2006.

Culbert KM, Slane JD, Klump KL. Genetics of eating disorders. In: Wonderlich S, Mitchell J, de Zwann M, et al, editors. Annual review of eating disorders part 3. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing; 2008:27-42.

Fassino S, Amianto F, Abbate-Daga G. The dynamic relationship of parental personality traits with the personality and psychopathology traits of anorectic and bulimic daughters. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50(3):232-239.

Favaro A, Monteleone P, Santonastaso P, et al. Psychobiology of eating disorders. In: Wonderlich S, Mitchell J, de Zwann M, et al, editors. Annual review of eating disorders part 2. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing, 2008.

Jones M, Luce KH, Osbourne MI, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of an Internet-facilitated intervention for reducing binge eating and overweight in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008;121:453-462.

Katzman D. Medical complications in adolescents with anorexia nervosa: a review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;37:S52-S59.

Kaye WH, Fudge JL, Paulus M. New insights into symptoms and neurocircuit function of anorexia nervosa. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(8):573-584.

Keel PK, Gravener JA. Sociocultural influences on eating disorders. In: Wonderlich S, Mitchell J, de Zwann M, et al, editors. Annual review of eating disorders part 2. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing, 2008.

Keel PK, Wolfe BE, Liddle RA, et al. Clinical features and physiological response to a test meal in purging disorder and bulimia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1038-1056.

Le Grange D, Crosby RD, Rathouz PJ, et al. A randomized controlled comparison of family-based treatment and supportive psychotherapy for adolescent bulimia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1049-1056.

Neumark-Sztainer D. Preventing obesity and eating disorders in adolescents: what can health care providers do? J Adolesc Health. 2009;44(3):206-213.

Rome ES, Ammerman S, Rosen DS, et al. Children and adolescents with eating disorders: the state of the art. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):e98-e108.

Schienle A, Schafer A, Hermann A, et al. Binge-eating disorder: reward sensitivity and brain activation to images of food. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:654-661.

Treasure J, DesForges J. Neuroimaging. In: Wonderlich S, Mitchell J, de Zwann M, et al, editors. Annual review of eating disorders part 2. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing, 2008.