Chapter 14 Ear Reconstruction

INTRODUCTION

Repair of the auricle can be traced back to India (600bce) with subsequent contributions by the Egyptians, Renaissance Italians, nineteenth-century surgeons, and finally German surgeons such as Diffenbach, who played a major role in refining auricle reconstruction.1 Much of the literature has focused on providing a reliable framework either after trauma or for microtia repair. These techniques range from harvesting costal cartilage buried in the abdomen to utilizing porous polyethylene.2

EAR AESTHETICS

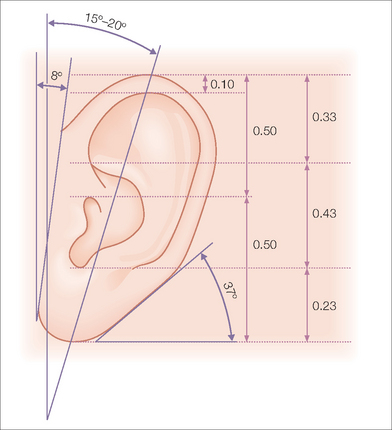

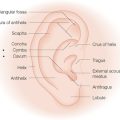

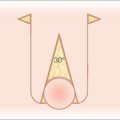

While auricle length is somewhat dependent on ethnicity (with African being the shortest and Asian being the longest), the length to width of the auricle should be slightly less than 2:1. Generally, the auricle protrudes from the scalp at a 20°–30° angle.3 A smooth contour outlined by the helical rim and bilateral symmetry are important universal aesthetic norms (Figure 14.1).

The superior aspect of the helical rim, defined by a horizontal line from its attachment to the scalp, needs to maintain a gentle curve without any acute angles. As the rim descends it almost approaches a 90° angle through its mid-portion. The lower third of the auricle curves at approximately a 45° angle as it descends into the earlobe. The lobule has great variability in its length and curvature. Generally, its width is one-third to one-half of the width of the superior portion of the helix. Earlobe length depends on ethnicity, but is approximately 2 cm on average.4 Earlobe thickness or “fleshiness” also varies from barely discernable from the helical rim to a very defined and separate structure. Earlobes tend to be asymmetrical and elongate with age.5 Aesthetically, the most important aspect of the earlobe is its independence as a separate cosmetic unit while maintaining the curved continuity of the helical rim.

EMBRYOLOGY

Embryologically, the ear develops from the first and second branchial arches. These arches arise as hillocks from the neck.6 During the early gestational period, they migrate cephalad. The outline of the ear is apparent early in the fetus at approximately the sixth week. Following birth, the external auricle grows quickly. By the age of 6, it has attained nearly adult size and proportions.

TOPOGRAPHY

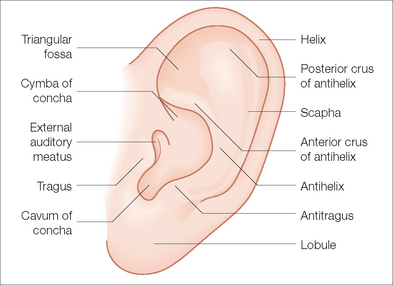

With its numerous ridges and valleys designed to improve acoustic reception, the external ear possesses the most complex topography of any cosmetic unit of the head and neck. The auricular framework is formed by cartilage. The earlobe like the nasal alar lobule is made of fibrofatty tissue. The medial-anterior facet of the auricle is characterized by perichondrium and thin skin tightly adherent to cartilage. The posterior-medial aspect has looser skin and some subcutaneous fat overlying the cartilaginous framework (Figure 14.2).

The major anterior landmarks of the external ear are the helix, the scapha, the antihelix, the concha, and the tragus and antitragus. Posteriorly, there are eminences that correspond to these anterior landmarks. Laterally, the helix actually begins with the crus, which originates at the superior aspect of the conchal bowl. The helix extends superiorly in a gentle curve. As it descends, there is a slight prominence known as the Darwinian tubercle. The helix continues its descent uninterrupted to the lobule. Proceeding medially from the helical rim is the scaphoid fossa. This is bounded by superior and inferior crura of the antihelix. As these two limbs of the antihelix stretch to meet the helical rim, a depression known as the triangular fossa bounded by these two limbs and the rim is created. Medially, these ridges bound the concha. This bowl-like structure can be divided into the cymba, which is bounded superiorly by the anterior crus of the antihelix and inferiorly by the crus of the helical rim. Inferior to the crus is the cavum, which has a more concave nature. Although the recessed nature of the concha makes it appear less important to the structure of the auricle, it actually acts as a brace between the mastoid and the remainder of the auricle. Medial-posteriorly, the concha leads to the external auditory canal. Lateral to the canal is the tragus, a roundish prominence. Opposing the tragus, across the conchal valley is the antitragus, a linear prominence at the origin of the antihelix. The posterior aspect of the ear is marked by various ridges and named prominences known as eminences, which correspond to the anterior anatomic landmarks. Aside from the intrinsic rigidity produced by the cartilaginous framework, the auricle is held in placed by small muscles and ligaments. The musculature can be divided into three extrinsic and three intrinsic bands.

Vasculature

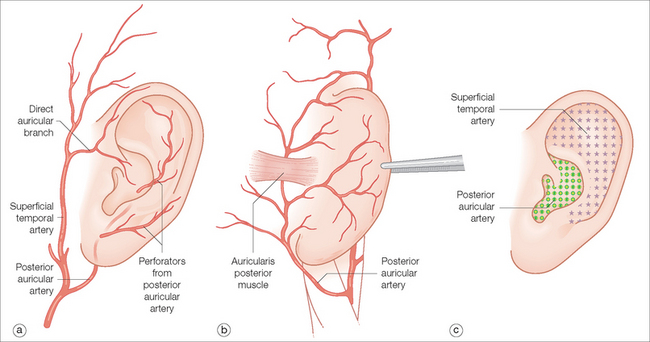

The blood supply is mainly supplied by the superficial temporal and the posterior auricular arteries. Both are branches of the external carotid. The superficial temporal artery and its branches, including the direct auricular, supply the anterior (lateral) surface of the ear, particularly the superior half. The posterior auricular artery supplies the entire medial (posterior) surface and has branches that perforate to the opposing surface, mainly supplying the lower half of the ear including the conchal bowl6 (Figure 14.3). Venous drainage occurs via corresponding named veins in addition to the retromandibular vein. These three veins flow into the external jugular vein.

Innervation

The external ear possesses an intricate sensory supply. The innervation is supplied by branches of the cervical nerve, the tenth cranial nerve, the trigeminal nerve, and the lesser occipital nerve. The greater auricular nerve, which originates from C2 and C3, extensively innervates the cranial aspect of the ear including the earlobe. It also branches out to the anterior surface and innervates most of the upper half of the auricle. The auriculotemporal nerve, a branch of V3, supplies the lateral aspect of the superior portion of the helix. The posterior surface of the helix and the eminences of the scapha and fossa triangularis are innervated by the mastoid branch of the lesser occipital nerve. Finally, Arnold’s nerve, a branch of the Vagus (CN10), supplies sensory nerves to the concha.7

RECONSTRUCTIVE OPTIONS

Skin Grafts

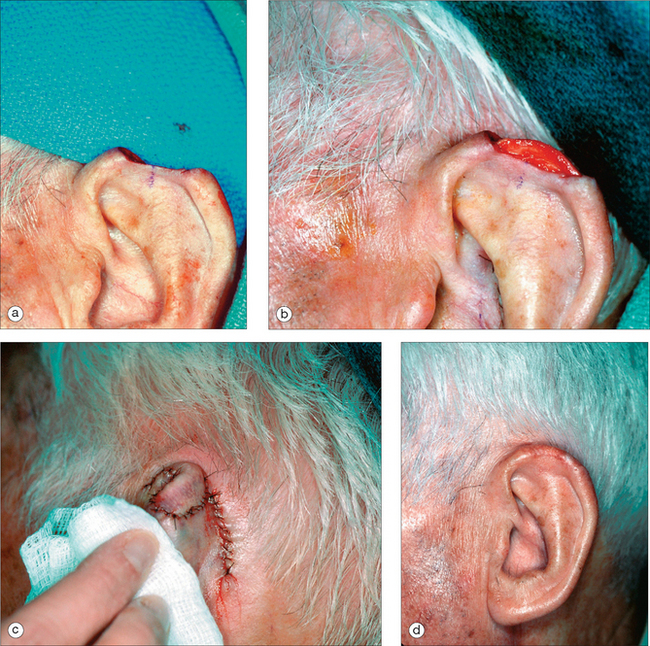

Full-thickness skin grafts have a wide application in resurfacing small to medium auricular defects. Grafts will have the highest chance of surviving if there is intact perichondrium. If the wound base consists of cartilage, multiple full-thickness perforations of the cartilage with a 2-mm punch can be used to facilitate the blood supply.8 Common donor areas include the pre- and postauricular sulci. The postauricular region is desirable since the scar will be hidden and it can heal by second intent or be closed primarily (Figure 14.4). The preauricular region may provide a slightly thicker graft. This site is a good choice when there are significant creases in which to hide the scar. It is rare that this donor site is left to heal by second intention. Generally, the donor site is from the ipsilateral side since this will decrease the need for patient repositioning.

Adjacent Tissue Transfer

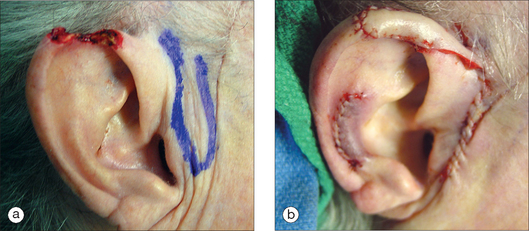

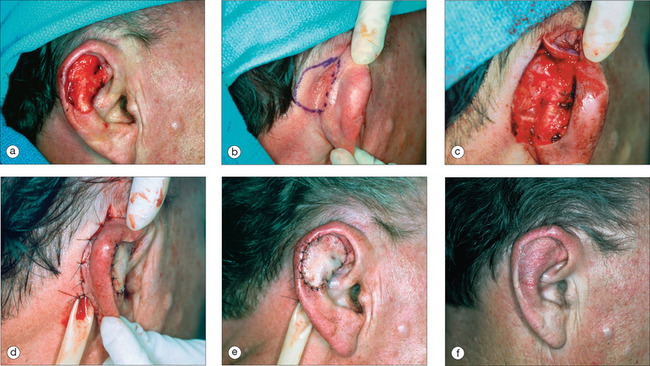

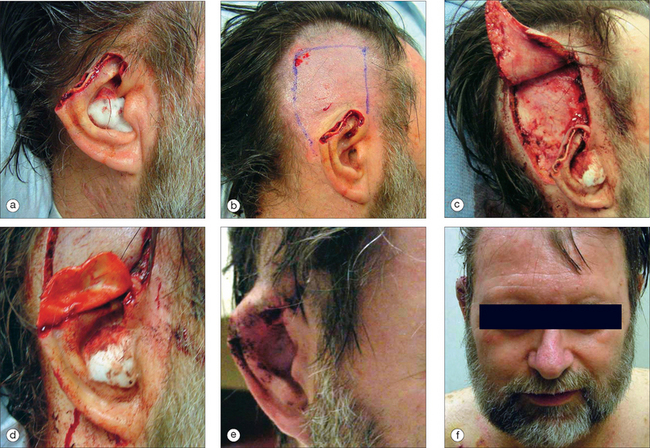

As in other head and neck defects, well-vascularized flaps with bulk that can be contoured are excellent reconstruction options for auricular defects. Random vascular pattern flaps based on the generous and redundant blood supply of the ear have a high survival rate. For larger defects, flaps may be staged, either from the pre- or postauricular regions (Figure 14.5) or from the temporal scalp. Wide undermining is necessary on the ear since there is minimal skin laxity, particularly on the lateral aspect of the external ear. Flaps may include cartilage, such as the chondrocutaneous helical advancement flap and the conchal bowl transposition flap for partial helical defects. Flaps may also be “tubed” in order to rebuild the helical rim from the pre- or postauricular sulci (Figure 14.6). For full-thickness conchal bowl or antihelix defects, posterior-based flaps may be bivalved in order to resurface both the lateral and medial side of the defect9,10 (Figures 14.7, 14.8).

Cartilage

Because the cartilage framework defines the characteristic shape of this cosmetic subunit, it is necessary to replace “like with like.” Using a staged flap without any subsurface support will result in a folded, floppy ear. The donor cartilage should be excised from a location where it will match the missing framework. The choice of donor site also needs to take into account the overall stability of the ear’s framework. Donor sites include the ipsilateral or contralateral conchal bowl, antihelix, and scapha (Figure 14.9). Grafts from the scapha or antihelix are more flexible and may be scored in order to provide a gentle curve. Harvesting a cartilage graft does not require skin excision. A skin flap can be elevated, the graft removed, and the flap sutured back into place with inter-rupted sutures and through-and-through sutures to minimize hematoma formation. In the conchal bowl, a firm pressure dressing will be needed because of excellent vasculature, and the increased risk of a hematoma. Costal cartilage is another donor source; however, it is usually reserved for near total or total ear reconstruction because of its rigidity.11 There is also increased risk for adverse effects in this donor site. For small skin–cartilage defects, a composite graft taken from the root of the helix is another alternative. However, in smokers, or those with vascular compromise, the composite graft will have a significantly decreased survival rate.

Regional Reconstruction

Upper Auricle

Tubed Flap

More extensive defects of the superior aspect of the helical rim can be repaired using a tubed pedicle flap.12 This can be a one- or two-stage flap transposed from the adjacent pre- or postauricular skin. When measuring the length of the flap, it should be at least 20% longer than the rim defect to take into account the transposition as well as the curvature of the helix. The tubed flap is typically superiorly based with its distal aspect sewn into the defect (Figure 14.10). A two-stage flap is utilized if there is intact skin that separates the donor site from the defect. If a two-stage flap is necessary, the pedicle is divided centrally after three weeks. The proximal pedicle is excised in a circular manner and repaired in a linear fashion. The distal pedicle, now replacing the defect, is thinned and inset with interrupted sutures. Careful sculpting of the distal flap tissue will provide a smooth and natural helical contour.

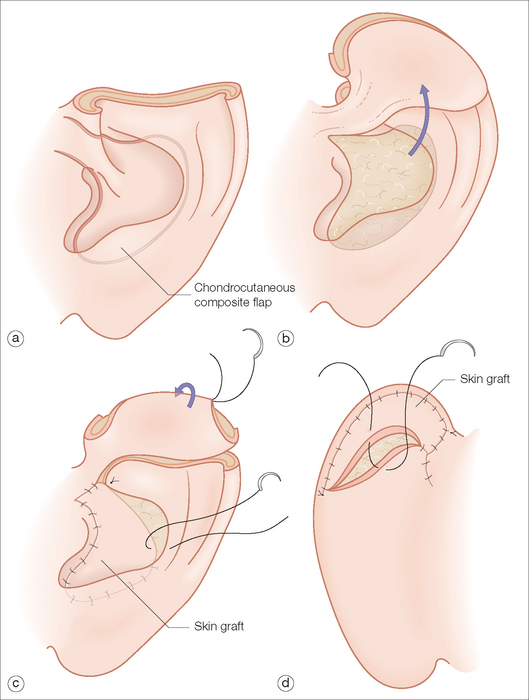

Composite Chondrocutaneous Flap

For defects that include the superior helical rim and the antihelix and are not amenable to a wedge excision, the chondrocutaneous flap from the conchal bowl is an elegant one-stage repair13 (Figure 14.11). The curved inferior border of the concha closely approximates that of the helical rim. A majority of the bowl composed of the skin and cartilage can be incised and transposed to fill the superior-oriented defect. The pedicle extends to the root of the ear and should be kept thin. Although it may be tempting to increase the width of the pedicle to ensure an adequate vascular supply, this may inhibit the mobility of the flap and actually compromise the blood supply. If extra length is needed, then the pedicle may be extended into the preauricular creases. The remainder of the conchal bowl is resurfaced with a full-thickness skin graft or allowed to heal by second intent.

Temporoparietal Flap

For large, complete defects of the superior helix and antihelix, the temporoparietal flap used in microtia repair and facial plastic surgery is an option.14,15 This flap is based on the superficial temporal artery traveling between the galea and the areolar tissue. It is a superiorly based, staged advancement flap. A skin graft is used to resurface this flap.

Although this flap is a significant addition to the arma-mentarium for repairing this area, it does possess several challenges. Because this area is not inherently mobile, the flap needs to be approximately 6 cm in length. This can result in extensive scarring and alopecia in the temporal region. This layer is extremely vascular, and hemostasis sometimes can be an issue. In addition, when elevating this flap anteriorly, it is important to be aware of the frontal branches of the facial nerve. One alternative is to incise a flap down to muscle and advance it over the defect. If the leading edge of the flap is in the sulcus at the border of the auricle, then hair growth will not be a factor, and a skin graft is not necessary (Figure 14.12). This flap is divided and contoured at three weeks.

Middle Auricle

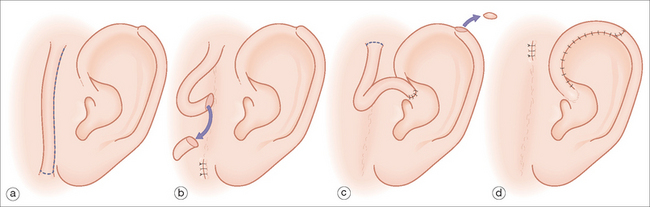

Because maintaining the outline of the ear is critical, it is rare to allow the middle portion of the helix to heal by second intent. Small superficial defects can be resurfaced with a full-thickness skin graft. Defects less than 1 cm that involve both the helix and antihelix can be converted into a wedge, and then closed in a multilayered fashion. Larger defects of the central portion of the helix can be repaired with a chondrocutaneous advancement flap.16 Depending on the size of the defect, a single full-thickness advancement flap can be mobilized. Because the skin laxity is more pronounced in the inferior rim including the earlobe, the advancement is typically inferiorly based. For larger defects, a bilateral flap may be necessary. The chondrocutaneous flap is a full-thickness flap (Figure 14.13). When suturing, it is important to approximate the cartilage with 4.0 absorbable interrupted sutures to prevent buckling of the helix. The anterior and posterior aspects of the skin are sutured with interrupted or running nylon for fast-absorbing gut sutures. When aligning the newly created helical rim, a vertical mattress suture to evert the skin edges may reduce the risk of notching. Alternatively, a Z-plasty may be used to prevent notching.

For full-thickness defects involving the middle helix and antihelix, a staged retroauricular flap is usually the best option17,18 (Figure 14.14). This reconstruction advances postauricular skin and has a robust random blood supply. Whereas in select cases it may be used alone to recreate the helix, it most often is used in conjunction with a cartilage graft harvested from the contralateral conchal bowl. Without the restoration of the cartilage framework, the helical rim may fold on itself or appear unnaturally flattened.

When marking, it is important to extend the flap into the postauricular sulcus. The length of the flap should be outlined so that it does not excessively pin the auricle, and has a 3–4:1 length-to-width ratio. The flap width should be slightly greater than the defect width to compensate for the helical curvature. The flap is inset with a layered closure. Vaseline gauze is placed in the postauricular sulcus. The flap is divided and contoured at three weeks. Division of the flap may be performed in two manners. Traditionally, the flap is marked so that there is enough length to wrap around the posterior aspect of the auricle. In patients with thin and delicate ears, this method may provide too much bulk. Alternatively, the posterior aspect may then be covered with a full-thickness skin graft. In patients where there is not a cartilage graft, the posterior aspect of the flap may be left to granulate. The remainder of the flap is sewn into the retroauricular space, and the sulcus may be left to granulate.

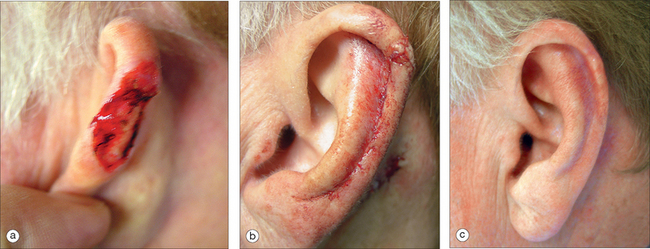

Lobule

In many ways, the lobule is a continuation of the helical rim and requires a reconstructive technique for restoring the smooth edge, curve, and symmetry. Lack of attention in restoring the lobule to its preoperative proportions will almost always be noticeable. In deciding whether to sacrifice shape or size, the latter has more room for compromise. For small lesions, a wedge excision with a primary closure designed to evert the wound edges will retain the natural shape. Alternatively, a Z-plasty will minimize notching. A small decrease in lobule size resulting from a small wedge excision is unlikely to draw attention. Because of the laxity of the lobule, primary closure is possible for sizable defects. Should these repairs create a noticeable disparity in earlobe size, then the contralateral earlobe can be reduced by a simultaneous or delayed wedge excision.19

In patients who wear earrings, care must be taken to minimize tension on the lobule. If a primary closure will distort the lobule or impact the patient’s ability to wear an earring, flaps or grafts should be considered to minimize distortion. A popular method of restoring the earlobe is the transposition flap20 (Figure 14.15). A one- or two-stage transposition flap can be designed from the pre- or postauricular crease. The secondary defect scars can be hidden with the crease and will be less visible in the postauricular crease. The preauricular skin is thicker and may be a better thickness and color match for the lobule. A staged infra-auricle flap can be used to repair inferior lobular defects. It possesses the advantage of a camouflaged scar, but it lacks mobility. For those individuals with a naturally shortened lobule, the helical rim may be advanced for coverage. Care should be taken not to distort the rim with this repair.

Concha

In many instances, defects in the conchal bowl can heal by second intent. An exception would be those defects directly adjacent to or including the external ear canal. In these areas, a wound allowed to heal by granulation has an increased risk of canal stenosis. Full-thickness skin grafts will minimize wound contraction and decrease the likelihood of this complication. For outer concha defects where some skin mobility exists, an advancement flap may be a reasonable option (Figure 14.16). For full-thickness defects, a postauricular island flap similar to that for the antihelix can be utilized, though the position of this flap will enter at the level of the concha. Occasionally pinning of the auricle may occur. This condition may be corrected by a subsequent Z-plasty to lengthen the postauricular scar line. Mellette has described a preauricular transposition flap that will also provide excellent coverage for large conchal bowl defects.19

PROSTHETICS AND WHEN TO REFER

Although it is within the skill set of dermasurgeons to reconstruct complex ear defects, there are circumstances when it would be better to consider a prosthesis or to refer to a facial plastic surgeon or plastic surgeon who specializes in total ear reconstruction. For the infirm patient, or one who truly does not desire further surgery, a prosthetic is a viable option.21 This alternative will lessen the patient’s potential morbidity, and be functionally viable since may patients’ primary concern is the ability to wear glasses.

1 Berghaus A, Toplak F. Surgical concepts for reconstruction of the auricle. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;112:388-397.

2 Berghaus A. Porous polyethylene in reconstructive head and neck surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1985;111:154-160.

3 Park SS, Hood RJ. Auricular reconstruction. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 2001;34:713-738.

4 Azaria R, Adler N, Silfen R, et al. Morphometry of the adult human earlobe: a study of 547 subjects and clinical application. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:2398-2402.

5 Mowlavi A, Meldrum DG, Wilhelmi BJ, Zook EG. Incidence of earlobe ptosis and psuedoptosis in patients seeking facial rejuvenation surgery and effects of aging. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:712-717.

6 Larrabee WF, Makielski KH. Surgical anatomy of the face. New York: Raven Press, 1993;177-185.

7 Vital JM, Grenier F, Dautheribes M, et al. An anatomic and dynamic study of the greater occiptal nerve (n. of Arnold). Surg Radiol Anat. 1989;11:205-210.

8 Ceilley RI, Bumstead RM, Paige WR. Delayed skin grafting. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1983;9:288-293.

9 Krespi YP, Ries WR, Shugar JMA, Sison GA. Auricular reconstruction with postauricular myocutaneous flap. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1983;91:193-196.

10 Ellabban MG, Maamoun MI, Elsharkawi M. The bi-pedicle post-auricular tube flap for reconstruction of partial ear defects. Br J Plast Surg. 2003;56:593-598.

11 Brent B. Ear reconstruction with an expansile framework of autogenous rib cartilage. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1974;53:619-628.

12 DiMascio D, Castagnetti F. Tubed flap interpolation in reconstruction of helical and earlobe defects. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:572-578.

13 Ramirez OM, Heckler FR. Reconstruction of nonmarginal defects of the ear with chondrocutaneous advancement flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;84:32-40.

14 Brent B, Byrd HS. Secondary ear reconstruction with cartilage grafts covered by axial, random, and free flaps of temporoparietal fascia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983;72:141-152.

15 Park SS, Wang TD. Temporoparietal fascial flap in auricular reconstruction. Facial Plast Surg. 1995;11:330-337.

16 Brent B. The acquired auricular deformity. A systematic approach to its analysis and reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1977;59:475-485.

17 Renard A. Postauricular flap based on a dermal pedicle for ear reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1981;68:159-165.

18 Johnson TM, Fader DJ. The staged retroauricular to auricular direct pedicle (interpolation) flap for helical ear reconstruction. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:975-978.

19 Mellette JR. Reconstruction of the ear. In: Principles and techniques of cutaneous surgery. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1996:363-380.

20 Griffiths RW. Earlobe reconstruction using a Limburg flap in six ears. Br J Plast Surg. 2003;56:620.

21 Renner G, Lane RV. Auricular reconstruction: an update. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;12:277-280.