20 Ear, nose and throat

The ear

Anatomy

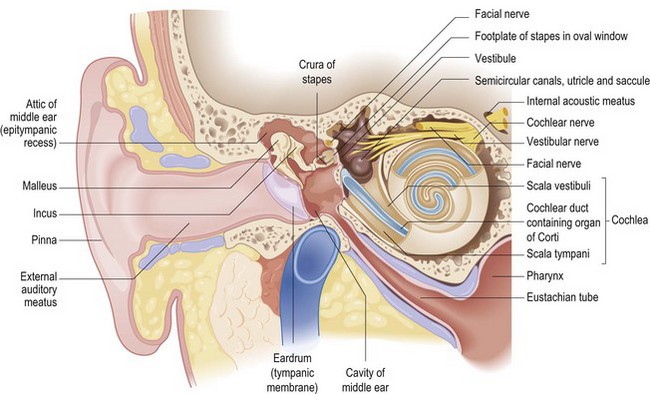

The ear (Fig. 20.1) consists of the external, middle and inner ears. The external ear consists of the pinna and external auditory canal (meatus). The cartilaginous pinna is covered with perichondrium and skin, forming the helix and antihelix. The meatus has an outer cartilaginous and an inner bony component. The skin overlying the external auditory meatus contains hair cells and modified sebaceous glands which produce wax (cerumen). Desquamated skin debris, mixed with cerumen, migrates outward from the drum and deep canal, and makes the external ear a self-cleaning system.

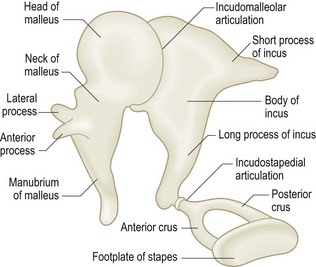

The opaque or semitranslucent eardrum (tympanic membrane) separates the middle and external ears (Fig. 20.2). The pars tensa, the lower part of the drum, is formed from an outer layer of skin, a middle layer of fibrous tissue and an inner layer of middle ear mucosa. It is attached to the annulus, a fibrous ring that stabilizes the drum to the surrounding bone. The pars flaccida, the upper part of the drum, may retract if there is prolonged negative middle ear pressure secondary to Eustachian tube dysfunction. The malleus, incus and stapes are three small connecting bones (ossicles) (Fig. 20.3) that transmit sound across the middle ear from the drum to the cochlea. The handle of the malleus lies within the fibrous layer of the pars tensa. Within the middle ear, the head of the malleus articulates with the incus in the attic, the upper portion of the middle ear space. The long process of the incus articulates with the stapes. This articulation (the incudostapedial joint) is liable to disruption from trauma or chronic infection. The stapes footplate sits in the oval window, and transmits and amplifies sound to the fluid-filled inner ear.

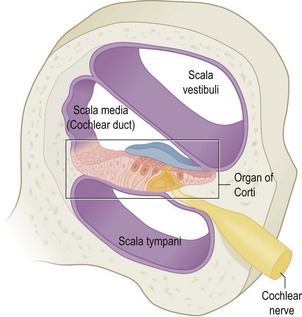

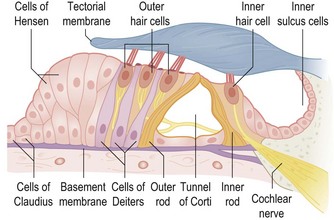

The inner ear has two portions. The cochlea (Fig. 20.4), the spiral organ of hearing, is a transducer that converts sound energy into digital nerve impulses that are transmitted by the eighth cranial nerve (cochlear) to the brainstem and thence to the auditory cortex. The organ of Corti (Fig. 20.5) within the cochlea contains hair cells that detect frequency-specific sound energy: low-frequency sounds are detected in the apical region, and high-frequency sounds are detected in the basal region. The inner ear is also concerned with balance. The semicircular canals and the vestibule contain receptors that detect angular and linear motion in the three cardinal x, y and z planes. The inner ears are only one component of the balance system; visual input and proprioception from joints and muscles are also important.

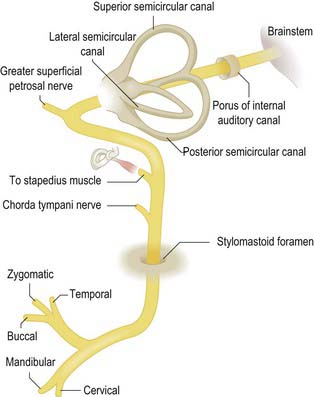

The facial (seventh cranial) nerve (Fig. 20.6) is important in otological practice. It runs from the brainstem through the cerebellopontine angle to the internal auditory meatus (IAM) with the cochlear and vestibular (eighth) nerves. The facial nerve passes through the temporal bone and leaves the skull through the stylomastoid foramen near the mastoid process. It may be damaged when there is suppurative middle ear disease or trauma. The chorda tympani leaves the descending portion of the facial nerve in the temporal bone to provide taste fibre innervation to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue. The facial nerve supplies the facial muscles through upper and lower divisions that arise as it passes through the parotid gland.

Symptoms of ear disease

The five main symptoms of ear disease are:

Otalgia

The main causes of otalgia are listed in Box 20.1. Of the otological causes, acute infection of the cartilage of the pinna (perichondritis) can be very painful. Malignant otitis externa is not neoplastic. It is due to infection (usually Pseudomonas) and can spread to the skull base, especially in diabetic or immunocompromised individuals.

Otorrhoea

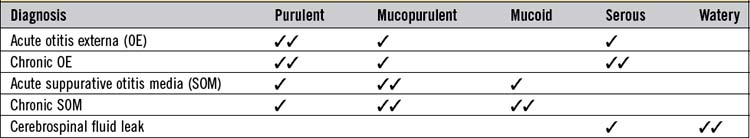

Pus draining from the ear varies in character depending on its origin (Table 20.1) A profuse mucoid discharge with pulsation suggests a tympanic membrane perforation. The length of history is important. Persistent discharge suggests chronic otitis media, with perforation (Table 20.2). Cholesteatoma usually begins with tympanic membrane retraction and blockage of migrating desquamated skin from the drum and external meatus. The retraction deepens and infection leads to destruction of middle ear structures, sometimes causing damage to the facial nerve or inner ear. The infection may spread outside the temporal bone, even causing meningitis or intracranial abscess. Bleeding from a chronically discharging ear is usually due to infection, but may rarely indicate malignant change. Cranial trauma followed by bleeding and leakage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) indicates fracture of the base of the skull.

| COM classification (synonym) | Otoscopic abnormalities |

|---|---|

| Healed COM (Healed perforation with or without tympanosclerosis) | Thinning and/or local or generalized opacification of the pars tensa without perforation or retraction |

| Inactive mucosal COM (Dry perforation) | Permanent perforation of the pars tensa but the middle ear mucosa is not inflamed |

| Active mucosal COM (Discharging perforation) | Permanent defect of the pars tensa with an inflamed middle ear mucosa that produces mucopus which may discharge |

| Inactive squamous epithelial COM (Retraction) | Retraction of the pars flaccida or pars tensa (usually posterosuperior) which has the potential to become active with retained debris |

| Active squamous epithelial (Cholesteatoma) | Retraction of the pars flaccida or tensa that has retained squamous epithelial debris and is associated with inflammation and the production of pus, often from the adjacent mucosa |

Hearing loss

Deafness may be gradual or sudden, bilateral or unilateral. There may be an obvious precipitating cause, such as trauma or noise exposure. There are two characteristics of hearing loss: to use the analogy of a radio, a decrease in volume, or a change in the tuning corresponding to impaired speech discrimination, so that words are not clear even with a hearing aid. Hearing loss may be conductive, sensorineural or mixed, with both conductive and sensorineural components (Box 20.2). Conductive deafness is due to disease in the external ear canal, tympanic membrane or middle ear. Characteristically, the patient retains normal speech discrimination. Sensory deafness implies pathology in the cochlea, and neural deafness implies pathology in the cochlear nerve or the central connections of hearing, but in practice this distinction is difficult to make and rarely useful, and the term sensorineural deafness is used instead. Sensorineural deafness causes impairment of speech discrimination with recruitment; the latter is an abnormal perception of the increase of intensity of sound with increasing signal volume that results from damage to the hair cells in the cochlea. This leads to a decreased functional dynamic range, so that a small increase in sound intensity is uncomfortable. The patient may also notice an apparent difference in the pitch or frequency of a tone between the two ears (diplacusis). Most hearing loss is gradually progressive and related to ageing. Deafness is often secondary to occupational or social noise exposure, and is often inherited. Many drugs are ototoxic, and there are associations between hereditary hearing loss and neurological and renal disorders. Occasionally, sensorineural hearing loss occurs suddenly. A cause is only rarely identifiable.

Box 20.2 Causes of deafness

Conductive

Sensorineural

Vertigo

Vertigo is an illusion of movement such that the patient either feels the world moving or has a sensation of moving in the world. Patients frequently have difficulty describing the symptom. Higher centre dysfunction, as in anxiety states or drug effects, may also cause dizziness. There are therefore many causes for symptomatic ‘dizziness’ (Box 20.3). A feeling of the room spinning associated with nausea or vomiting suggests an acute labyrinthine cause, especially if there are changes in hearing or tinnitus. Fortunately, most acute vestibular events are self-limiting, because even if one vestibular system is abnormal, the central connections can ‘reset’ the system over a period of a few days. The elderly are less able to compensate. In all age groups, vertigo may cause residual vague imbalance, particularly in association with movement or after alcohol ingestion. It is important to test for positional changes, as the commonest cause of vestibular vertigo is benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), secondary to loose debris floating in the posterior semicircular canal.

Clinical examination of the ear and hearing

Pinna and postauricular area

First, inspect the pinna and the surrounding skin. Congenital abnormalities may be associated with accessory skin tags, abnormal cartilaginous fragments in the skin surrounding the ear or small pits and sinuses. Look also for any lymphadenopathy (associated with otis externa or scalp cellulitis) and for surgical scars. A hot, tender postaural swelling, pushing the pinna forward, suggests mastoid infection (Fig. 20.7). Incomplete development of the ear (microtia) occurs with narrowing (atresia) of the external meatus, but the auricle can also be displaced from its normal position (melotia) or pathologically enlarged (macrotia). These abnormalities may be associated with cysts or infection in a preauricular sinus.

External ear canal

Inspect the external auditory canal using a hand-held otoscope (Fig. 20.8). To bring the cartilaginous meatus into line with the bony canal, retract the pinna backwards and upwards. Always use the largest speculum that will comfortably fit the ear canal. Hold the otoscope like a pen between thumb and index finger, with the ulnar border of your hand resting gently against the side of the patient’s head. In this way, any movement of the patient’s head during the examination causes synchronous movement of the speculum, limiting any risk of accidental injury to the ear canal. With a young child, sit him on his parent’s lap with the head and shoulder held (Fig 20.9).

The tympanic membrane

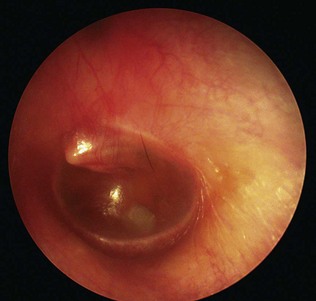

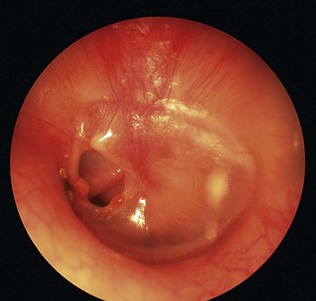

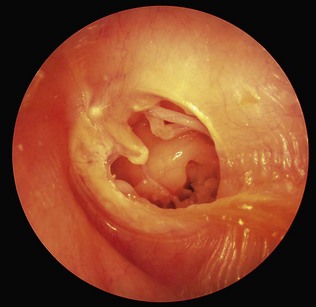

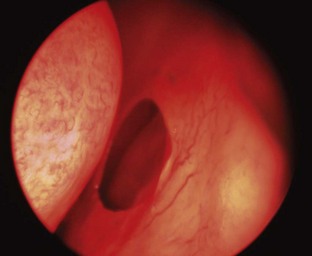

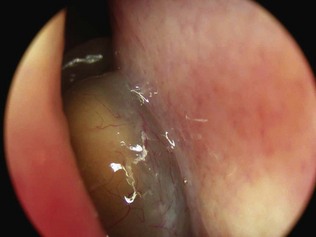

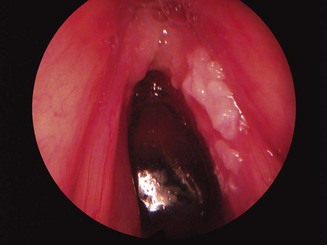

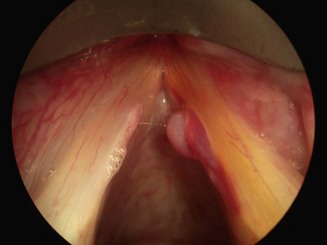

The hand-held otoscope is satisfactory for most examinations, but the outpatient microscope offers the best view. Be familiar with the variability in appearance of the normal drum. The most common abnormality is tympanosclerosis (Fig. 20.10), which consists of white chalky patches in the drum caused by hyaline degeneration of the fibrous layer due to previous infection. Prolonged negative middle ear pressure may cause the drum to become thinned and atelectatic (Fig. 20.11), either diffusely or with a retraction pocket. Eustachian tube dysfunction and/or acute otitis media may cause a middle ear effusion (Fig. 20.12). Fluid behind the drum is often obvious, but when the drum is opaque, increased vascularity or retraction are useful clues. Perforations of the pars tensa are either central or marginal (Fig. 20.13). Marginal perforations extend to the annulus and may be associated with cholesteatoma (Fig. 20.14), whereas with central perforations there is a rim of retained membrane between the defect and the annulus. Both are described by their position in relation to the handle of the malleus (anterior, posterior or inferior) and by their size (Fig. 20.15).

Figure 20.10 A right tympanic membrane showing marked posterior tympanosclerosis and a small anterior perforation.

Figure 20.11 A left tympanic membrane showing atelectasis and posterior retraction on to the long process of the incus.

The facial nerve

Test the facial movements. Unilateral weakness is much easier to identify than bilateral weakness. A peripheral facial palsy can be graded using the House-Brackmann scale (Table 20.3). Function of the greater superficial petrosal nerve can be tested with Schirmer’s test: absorbent paper strips are applied to the inferior margin of the eye to detect tear formation (Ch. 19). Chorda tympani function can be tested by the sense of taste and by electrogustometry.

| Grade | Function |

|---|---|

| I | Normal |

| II |

Clinical assessment of hearing

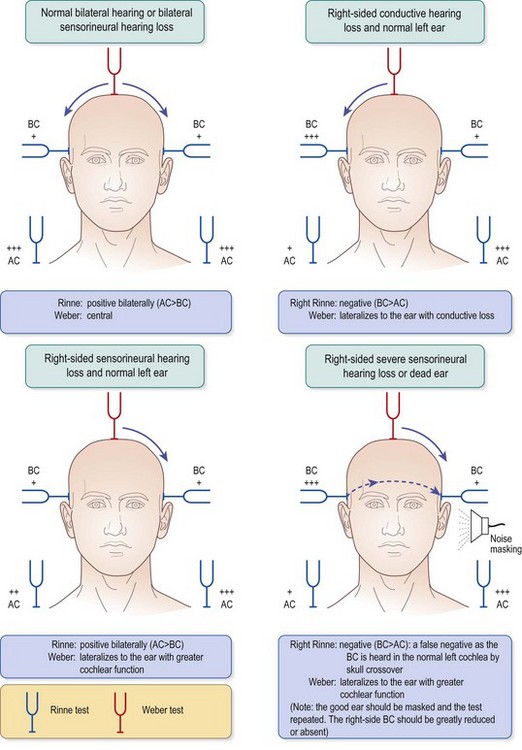

The Rinne test (Fig. 20.16) compares hearing by air and bone conduction using a 512- or 256-Hz tuning fork. Strike the tuning fork and hold it near the external ear canal with the prongs vibrating towards the meatus (air conduction) and then against the mastoid process (bone conduction). Ask the patient which sound was louder. In subjects with normal hearing and those with sensorineural loss, air conduction is better than bone conduction (Rinne positive.) In conductive deafness, bone conduction is louder (Rinne negative), although patients with a small conductive loss (up to 30 dB) may remain Rinne positive; it is only when the difference between air and bone conduction exceeds 40 dB that the Rinne test is consistently negative. Moreover, patients with a profound unilateral sensorineural hearing loss will report a Rinne-negative response if the contralateral ear has normal or reasonable hearing. This is because although the vibrating tuning fork held adjacent to the test ear will only be heard in that ear, the same tuning fork placed on the mastoid process will also be heard in the non-test ear. For these reasons, masking (by rubbing) the non-test ear should always validate a negative response. If there is doubt, a Barany box should be used to mask the contralateral ear.

Clinical assessment of balance

The unsteady patient requires a full neuro-otological examination. It is also necessary to examine the cardiovascular system (see Ch. 11). The aim is to localize the site of any potential lesion and possibly confirm a diagnosis, although sometimes all that is possible is to differentiate between central (brainstem) and peripheral (labyrinthine) lesions.

Examine the cranial nerves (see Ch. 14), particularly testing the eyes and for nystagmus.

Examine the cranial nerves (see Ch. 14), particularly testing the eyes and for nystagmus.

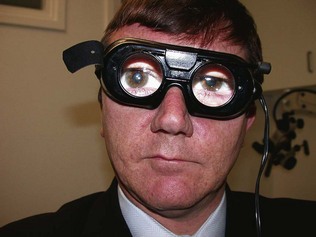

Nystagmus (see Ch. 19). The characteristic saw-toothed nystagmus of vestibular disease has a slow (labyrinthine) and a fast (central) component and is enhanced by movement of the eyes in the direction of the fast phase. Eye movements can also be assessed using Frenzel’s glasses (Fig. 20.17). These are illuminated and have 20-dioptre lenses that abolish visual fixation for the patient, thereby possibly unmasking nystagmus.

Nystagmus (see Ch. 19). The characteristic saw-toothed nystagmus of vestibular disease has a slow (labyrinthine) and a fast (central) component and is enhanced by movement of the eyes in the direction of the fast phase. Eye movements can also be assessed using Frenzel’s glasses (Fig. 20.17). These are illuminated and have 20-dioptre lenses that abolish visual fixation for the patient, thereby possibly unmasking nystagmus.

Pursuit (slow) movements, which depend on the fovea and the occipital cortex of the brain, are seen when the patient tracks an object moved slowly horizontally and vertically across the visual field about 35 cm away.

Pursuit (slow) movements, which depend on the fovea and the occipital cortex of the brain, are seen when the patient tracks an object moved slowly horizontally and vertically across the visual field about 35 cm away.

Saccadic movements are driven by the frontal lobes and the pontine gaze centres are seen when the patient alternates the gaze rapidly between two objects held approximately 30° apart.

Saccadic movements are driven by the frontal lobes and the pontine gaze centres are seen when the patient alternates the gaze rapidly between two objects held approximately 30° apart.

Romberg’s test. The patient stands with the feet together, initially with the eyes open and then closed. Patients with disorders of the spinal posterior columns (impaired position sense) will sway or fall with closed eyes, but will stand normally if open. Patients with uncompensated unilateral labyrinthine dysfunction are unstable, tending to fall to the side of the lesion. Patients with central dysfunction sway to both sides, whether the eyes are open or shut.

Romberg’s test. The patient stands with the feet together, initially with the eyes open and then closed. Patients with disorders of the spinal posterior columns (impaired position sense) will sway or fall with closed eyes, but will stand normally if open. Patients with uncompensated unilateral labyrinthine dysfunction are unstable, tending to fall to the side of the lesion. Patients with central dysfunction sway to both sides, whether the eyes are open or shut.

Unterberger’s stepping test has the patient standing with arms outstretched and eyes closed, and taking steps on the spot. Unilateral vestibular hypofunction leads to rotation to the affected side.

Unterberger’s stepping test has the patient standing with arms outstretched and eyes closed, and taking steps on the spot. Unilateral vestibular hypofunction leads to rotation to the affected side.

Gait assessment. The patient walks heel to toe with eyes first open and then closed. The patient with a cerebellar lesion is unable to do either. The patient with a peripheral vestibular lesion will struggle, particularly with the eyes closed.

Gait assessment. The patient walks heel to toe with eyes first open and then closed. The patient with a cerebellar lesion is unable to do either. The patient with a peripheral vestibular lesion will struggle, particularly with the eyes closed.

The Dix-Hallpike test assesses the effect of positional change. The patient sits on an examination couch. First test neck movements, to make sure they are free and painless. The head is then turned 45° to the side of test. The patient is laid back rapidly with his head extended over the end of the bed (Fig. 20.18). The classic response in BPPV involves a variable latent period when nothing happens. There is then a torsional nystagmus beating to the lower ear, with a variable feeling of vertigo. This lasts perhaps 5-30 seconds. With repetition, the response becomes less or absent. The condition is caused by debris in the posterior semicircular canal. It is frequently self-limiting, but if it persists it may be cured by the Epley particle repositioning manoeuvre. Other positive results are possible. Persistent immediate positional nystagmus without vertigo implies central pathology.

The Dix-Hallpike test assesses the effect of positional change. The patient sits on an examination couch. First test neck movements, to make sure they are free and painless. The head is then turned 45° to the side of test. The patient is laid back rapidly with his head extended over the end of the bed (Fig. 20.18). The classic response in BPPV involves a variable latent period when nothing happens. There is then a torsional nystagmus beating to the lower ear, with a variable feeling of vertigo. This lasts perhaps 5-30 seconds. With repetition, the response becomes less or absent. The condition is caused by debris in the posterior semicircular canal. It is frequently self-limiting, but if it persists it may be cured by the Epley particle repositioning manoeuvre. Other positive results are possible. Persistent immediate positional nystagmus without vertigo implies central pathology.

Special investigations of hearing

Pure tone audiometry

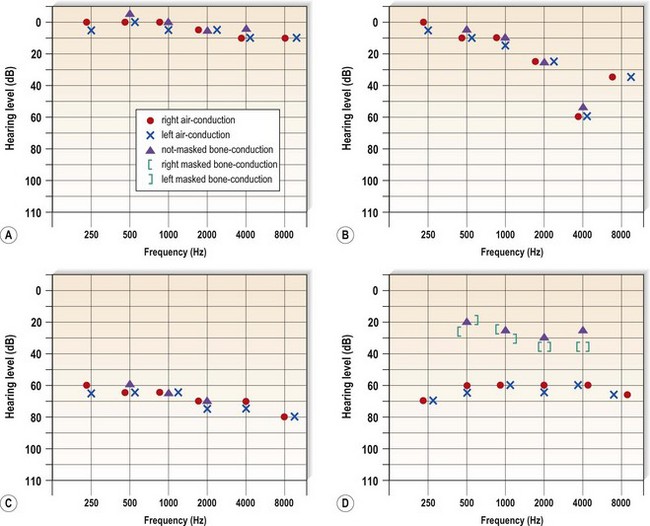

A single-frequency tone is presented at standardized levels into each ear in turn. This is done in noise-free surroundings, usually in a soundproofed booth (Fig. 20.19). Air conduction is tested first through headphones. A level well above threshold, as predicted by free field testing, is chosen and the patient responds when he hears the sound. The intensity is then reduced in 10-dB steps until the patient cannot hear it. It is then increased in 5-dB steps to establish the quietest sound that can be heard – the threshold. The better ear is tested first at 1, 2, 4 and 8 kHz, then at 250 and 500 Hz (Fig. 20.20). Bone conduction tests are performed using a vibrating headset applied to the mastoid. In conductive loss, the difference is called the air-bone gap. This may be correctible by surgery to the middle ear and tympanic membrane.

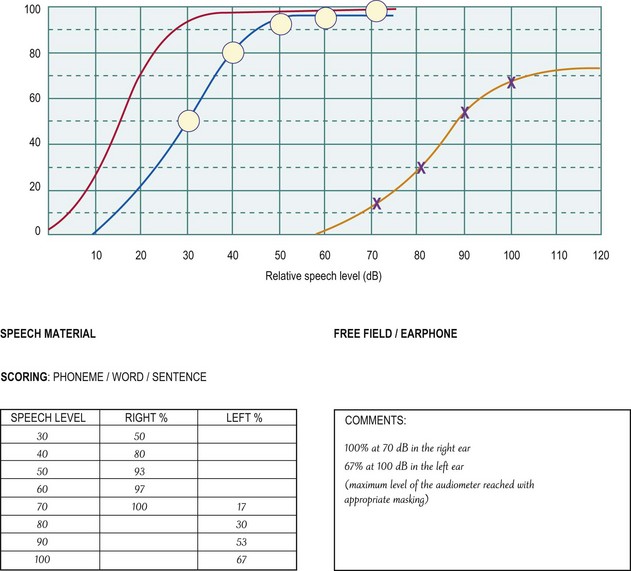

Speech audiometry

A pure tone audiogram does not test discrimination. A speech audiogram measures the patient’s ability to recognize words from phonetically balanced lists delivered at different sound levels to the test ear from a tape recording. The percentage of words correctly repeated by the subject is noted at each level. With normal hearing, all words are heard (100% optimal speech discrimination – ODS) at a sound intensity of 40 dB. Patients with sensorineural deafness are often unable to achieve 100% ODS and, in particular, patients with neural/retrocochlear loss have poor ODS (Fig. 20.21).

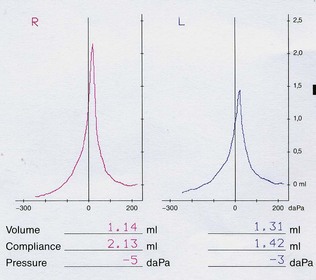

Tympanometry

An earpiece is inserted into the external meatus through which pass three channels. The first delivers a continuous tone into the ear canal during the test (probe tone); the second has a microphone to record the sound intensity level within the ear canal; the third channel connects to a manometer so that the pressure within the canal can be altered (Fig. 20.22).

The external meatus is a rigid tube with a compliant end (the drum). Normally the middle ear and ear canal pressures are equal, and most of the sound introduced into the meatus is transmitted into the ear; only a minimum of sound energy is reflected back and measured by the microphone. Changing the pressure difference between the external and the middle ear causes the tympanic membrane to become less compliant. This increases the sound energy reflected back to the probe. These changes are plotted graphically on a tympanogram (Fig. 20.23). The test also measures the volume of the canal: a large volume indicates a tympanic perforation. Impedance (the reciprocal of compliance) is increased when the tympanic membrane is thickened or the middle ear has fluid, and is decreased when the drum is hypermobile or atrophic. Tympanometry is an objective test. It has particular value in children in the assessment of glue ear.

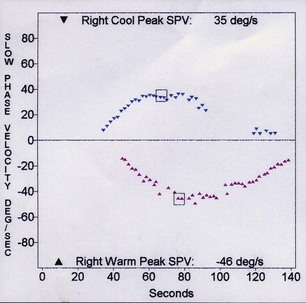

Special tests of balance

Caloric testing is the most commonly performed routine test of the vestibular end-organ. The patient lies on a couch with the head up 30°, in order to bring the lateral semicircular canals into the vertical plane. With the patient fixing on a point in central gaze, each external ear canal is irrigated with water at 30°C, and then at 44°C for 30-40 seconds, with suitable intervals. Cold water induces nystagmus away from the irrigated ear, and the opposite for warm water (COWS: cold opposite, warm same). The induced nystagmus is recorded and analysed using electronystagmography (Fig. 20.24). Nystagmus can be enhanced by the abolition of optic fixation (see Frenzel’s glasses above). The videonystagmoscope also allows monitoring of this response (Fig. 20.25) and allows recordings to be made. Peripheral lesions tend to cause a diminished response on one side (a canal paresis). A directional preponderance may be due to central disorders, especially in the brainstem.

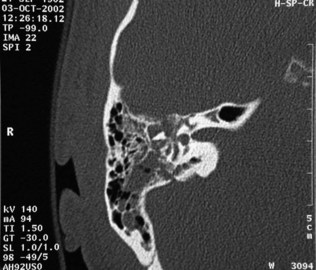

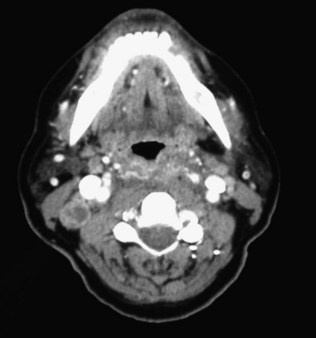

Radiological examination

Computed tomography (CT) scanning is the investigation of choice, but is not a substitute for clinical assessment of chronic ear disease. It is not specifically diagnostic of cholesteatoma (Fig. 20.26), but is useful in cranial trauma (Fig. 20.27) and in the evaluation of temporal bone neoplasia. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more useful in identifying soft tissue abnormalities in the cerebellopontine angle, especially vestibular schwannoma (Fig. 20.28). These present with asymmetric sensorineural hearing loss. MRI also helps assess tumour spread outside the temporal bone. MR angiography helps assessment of pulsatile tinnitus and vascular lesions. Formal angiography is useful for embolization of vascular tumours.

The nose and paranasal sinuses

Anatomy

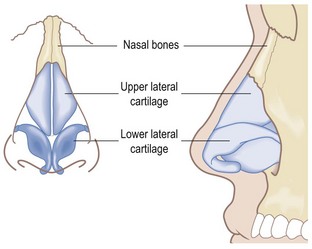

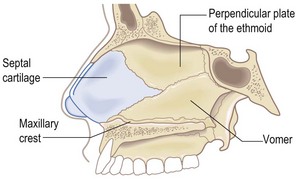

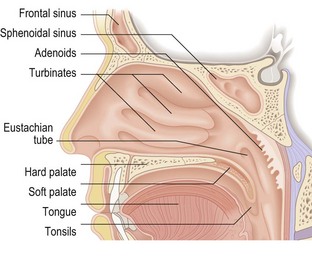

The nose (Box 20.4) is formed by the two nasal bones, which articulate with the nasal process of the maxilla on each side. The lateral cartilages provide support for the nostrils, especially in inspiration (Fig. 20.29). The nasal cavity is divided by the nasal septum, formed of cartilage anteriorly and bone posteriorly (Fig. 20.30). The lateral wall of the nose is formed by the three nasal turbinate bones; inferior, middle and superior (Fig. 20.31). Under each turbinate is a corresponding meatus. The nose constantly produces mucus – a pint a day – which is constantly propelled backwards by the cilia to the posterior choanae, whence it is swallowed, usually unnoticed.

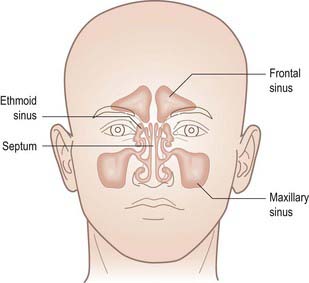

The paranasal sinuses are air-filled spaces in the bones of the facial skeleton (Figs 20.31 and 20.32). They comprise the paired maxillary, frontal and ethmoid sinuses and the unpaired but bisected sphenoid sinus, and form the structure of the adult face. The ethmoidal cells or labyrinth comprises a number of small bony cells. The sinuses open into the nose via small drainage channels (ostia). Their mucus is swept by cilia through the ostia to be mixed with mucus secreted by the nose. The middle meatus is the common pathway for drainage from the maxillary, the anterior ethmoid and the frontal sinuses. The anterior ethmoids are important because disease in these areas will compromise maxillary and frontal sinus drainage. Blockage of the ostia due to inflammation in the nose, with retention of mucus and secondary infection, is the presumed mechanism for sinus infection (rhinosinusitis). The upper teeth are closely related to the floor of the maxillary sinus: infection here may lead to sinus problems.

Symptoms of nasal disease

The important symptoms of nasal and sinus disease are:

Facial pain

Pain in the face is very common, but pain limited to the nose is rare. Pain centred over a sinus may indicate infection or, rarely, a malignancy. There are many causes of facial pain. Some, such as cluster headache (causing transient nasal blockage and rhinorrhoea) and trigeminal neuralgia, are functional disorders, with well-defined features (see Ch. 14). Structural disorders, such as infection or tumour involving facial structures, may also present with facial pain. Investigation should usually include imaging by CT or MRI.

Examination of the nose and face

Examine the nasal vestibule and intranasal contents by gently pushing the tip of the nose upwards with a finger, preferably using reflected illumination from a head mirror. The nasal vestibule is lined with skin and contains vibrissae (thicker hairs): these become prominent in older men. Inspect the anterior nasal cavity with Thudicum’s nasal speculum or an otoscope (Fig. 20.33). The nasal septum is rarely completely straight but should not be so bent that it is not possible to see the anterior end of the inferior turbinate. The majority of nasal resistance to airflow occurs in the front of the nose. Look for any area of granulation on the nasal septum and for any perforation (Fig. 20.34). Perforations may be secondary to cocaine snorting, digital trauma (nose-picking), surgical trauma, granulomatous conditions or inhalation of industrial dusts, notably nickel and chrome.

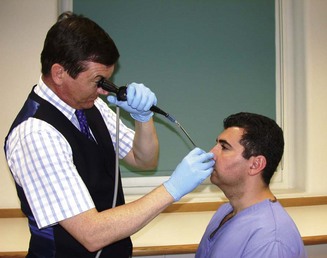

Nasal polyps are usually easily identifiable by their pale colour (Fig. 20.35) and their softness and lack of sensitivity to probing. In a child, an apparent polyp may be seen arising from the roof of the nose: this should not be probed as it may be the intranasal presentation of a meningocele. In children and adults, airflow through a patent nostril causes misting on a cold metal tongue depressor or mirror held at the nose. In a neonate, nasal patency is best estimated by observing any movement of a wisp of cotton wool held in front of each nostril, after blocking each in turn with the thumb. Nasal endoscopy (Fig. 20.36), after applying a topical decongestant such as xylometazoline with topical lidocaine anaesthesia, allows inspection of the middle meatus for oedema, draining pus or polyps. The postnasal space and the opening of the Eustachian tube (Fig. 20.37) can be seen, with the fossa of Rosenmuller, the site of origin of postnasal space carcinomas, lying directly above and behind. In children and young adults, look for adenoidal swelling.

Special tests

Allergy testing

If allergic symptoms are severe, there is merit in confirming extrinsic allergy by skin-prick testing (see Ch. 15). An important component of treating allergy is allergen avoidance and certainty of responsible allergens may encourage compliance. The common inhalant allergens (Box 20.5), together with any agents that have been suspected from the history, should be tested and compared to positive and negative controls (histamine and saline). Unfortunately, however, a negative response does not definitely exclude atopy. If clinical suspicion is strong, the radioallergosorbent test (RAST), which measures specific IgE in blood, may be considered, although it is expensive. Nasal provocation tests are time-consuming, as only one allergen at a time can be tested.

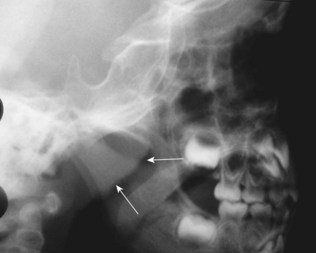

Radiological examination

Plain X-rays are unreliable in the management of sinus disease but may be helpful in the absence of more specialized tests. A lateral X-ray may be useful in estimating the degree of adenoidal hypertrophy in young children (Fig. 20.38). Endoscopic nasal examination and CT scanning are the investigations of choice for sinus disease (Fig. 20.39). CT is useful in the management of chronic infection, trauma and neoplasia. However, there is a radiation dosage to the eyes and the investigation should be used only when the diagnosis is uncertain or to provide accurate anatomical information before surgery. MRI is less useful in sinus disease because of difficulties in interpretation. MRI is highly sensitive to changes in the mucosal lining of the sinuses. However, it tends to overdiagnose and interpretation requires caution. It does have value in assessing spread of sinus neoplasia.

The throat

Anatomy

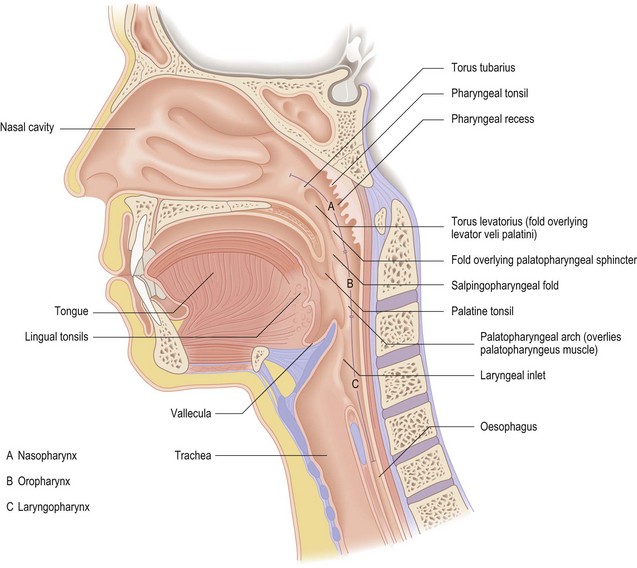

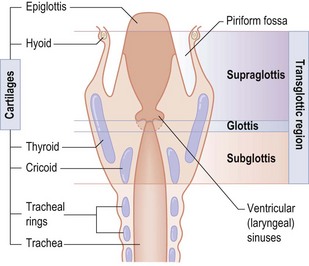

The throat includes the oral cavity, the pharynx (oropharynx, nasopharynx and hypopharynx), the larynx and the major salivary glands. The oral cavity extends from the lips to the anterior faucial pillars. The oral cavity proper is bounded by the teeth laterally, the tongue and floor of the mouth inferiorly and the hard and soft palate superiorly. The pharynx extends from the base of the skull to the cricopharyngeal sphincter (Fig. 20.40). The oropharynx is bounded above by the soft palate and below by the upper surface of the epiglottis. Its anterior margin is defined laterally by the anterior faucial pillar, containing the palatoglossus muscle, and by the posterior third of the tongue. The posterior pharyngeal wall is its posterior boundary. The palatine tonsils are situated laterally between the anterior and posterior pillars of the fauces. The base of the tongue contains the lingual tonsils. This lymphoid tissue, together with the adenoids and the tubal tonsil (lymphoid tissue around the Eustachian tube opening), makes up Waldeyer’s ring, an important line of immunological defence. The hypopharynx consists of the posterior pharyngeal wall, the piriform fossae and the postcricoid area. The piriform fossae, which comprise the lateral walls of the pharynx adjacent to the larynx, are the routes by which food is passed into the upper oesophagus. The larynx is a rigid structure consisting of cartilages, the most prominent of which are the paired thyroid cartilages, which articulate with the cricoid cartilage below. The epiglottis is attached to the inner surface of the thyroid cartilage and aids the separation of air and food passages during swallowing. The larynx consists of three compartments (Fig. 20.41): glottis, supraglottis and subglottis. The glottis is formed by the vocal folds. The glottis has poor lymphatic drainage, which may help to delay the spread of malignancy from this area. The epiglottis extends from the false cords below to the hyoid bone above. It has a rich lymphatic drainage, and therefore malignancy in this area is more frequently associated with metastatic disease. The subglottis is the narrowest part of the upper respiratory tract and extends from the glottis to the lower border of the cricoid.

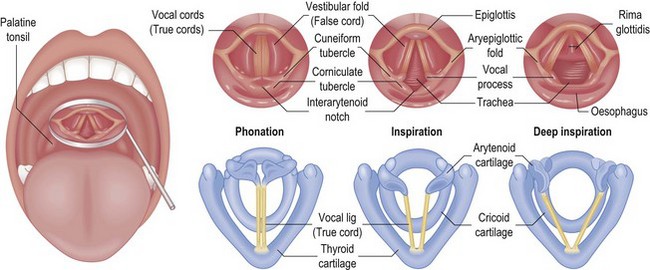

The prime function of the larynx is to separate breathing and swallowing, thereby protecting the airway. Voice production is a secondary function that has arisen with evolution. Phonation occurs with movement of the vocal folds into the midline (Fig. 20.42). Changes in volume of the voice are caused by alterations in the subglottic pressure, whereas alterations in pitch are due to modification of the length and tension of the vocal folds. The quality of this basic laryngeal sound is modulated by resonance in the pharynx, air sinuses, mouth and nose.

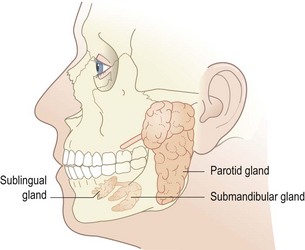

There are three paired major salivary glands (Fig. 20.43). The parotid gland lies anterior to the ear. Its duct opens opposite the second upper molar tooth. The submandibular gland lies far posterior in the floor of the mouth and may be palpated in the neck, under the mandible. Its duct opens anteriorly in the floor of the mouth adjacent to the frenulum of the tongue. The smaller sublingual gland lies anteriorly in the floor of the mouth and its duct joins the submandibular duct.

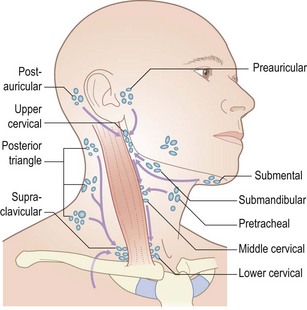

The lymph nodes of the head and neck (Fig. 20.44) provide a barrier to the spread of disease, whether inflammatory or neoplastic. Enlargement implies that there is either primary disease within the nodes or that they have become involved secondary to pathology in the areas they drain. Occasionally they may become involved by pathology below the clavicle.

Symptoms of throat disease

Patients with throat disorders present with:

Oral ulceration and pain

An ulcer is the commonest oral lesion. Traumatic ulcers heal quickly, although, if due to ill-fitting dentures or broken teeth, will rapidly recur, if not fail to heal. Aphthous ulcers are small, painful superficial ulcers of the tongue, buccal mucosa and palate, of uncertain cause which are painful but generally heal quickly. There is a high incidence of recurrence. Oral carcinoma may present as an ulcer and is frequently painless. Sometimes there will be other symptoms such as bleeding, loose teeth or halitosis but suspicious non-resolving lesions need to be biopsied. Thrush (fungal infection with Candida albicans) is a frequent cause of white patches or pain. Rare causes of ulceration include Crohn’s disease and Behçet’s syndrome. The sensation of ‘burning mouth’ has a number of causes outlined in Box 20.6.

Stridor and stertor

Stridor is noisy breathing associated with upper airway obstruction at the laryngeal level (Box 20.7). Stertor is noisy breathing at the oropharyngeal level and is nearly always caused by adenotonsillar hypertrophy. Epiglottitis is particularly important in infants and small children up to the age of 7 years. It is associated with infection by Haemophilus influenzae type B, and may present with rapidly progressive airway obstruction and dyspnoea, fever, pharyngeal pain and drooling. Vaccination has reduced its incidence. Immediate antibiotic therapy may need to be supplemented by intubation or even tracheostomy. In adults, laryngeal carcinoma may cause stridor owing to direct blockage of the airway, to fixation of the vocal fold or with recurrent laryngeal nerve involvement. Croup, acute laryngotracheobronchitis in young children, causes less severe airway obstruction. The thick tenacious secretions are relieved by air humidification.

Dysphonia

Dysphonia or hoarseness covers a range of symptoms, from subtle changes noticed by professional voice users to aphonia, when there is no voice. It may be caused by structural problems affecting the vocal fold, or by neurological disease (Box 20.8). Hoarseness followed by increasing airway obstruction is the typical presentation of a laryngeal neoplasm (Fig. 20.45). Damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve anywhere along its course usually leads to hoarseness, although compensation from the unaffected side will limit symptoms. A lesion of the vagus above the exit of the superior laryngeal nerve produces a more breathy voice, as there is also loss of cricothyroid function. Acute vocal abuse and acute inflammation causes dysphonia, which is usually self-limiting. Long-term vocal abuse may lead to a number of changes of the vocal folds: singer’s nodules, polyps (Fig. 20.46) or Reinke’s oedema. These will often respond to speech therapy, although surgery may be necessary. It is also worth considering whether gastro-oesophageal (laryngopharyngeal) reflux may be implicated. Malignancy should be considered in any patient with dysphonia of more than 4 weeks’ duration.

Dysphagia

Any lesion that interrupts the normal sequence of coordinated muscular activity necessary for swallowing may cause dysphagia (Box 20.9). Dysphagia results from structural disease of the pharyngo-oesophagus or from neurological disorders. Persistent dysphagia, especially if associated with regurgitation of undigested food, weight loss, dysphonia, otalgia or a mass in the neck, requires urgent investigation. Pooling of saliva in the piriform fossa seen at laryngoscopy implies obstruction in the cervical oesophagus or in the postcricoid area (see Ch. 12 for discussion of dysphagia below the cricopharyngeus).

Box 20.9 Causes of dysphagia

Lump in the neck

The causes of salivary gland swelling are outlined in Box 20.10.

The neck has a rich lymphatic system of nodes and channels that drain the head and neck (see Fig. 20.44). The deep cervical lymph nodes run in the carotid sheath. The most prominent of these is the jugulodigastric node, which can be palpated just posterior to the angle of the mandible and anterior to the anterior edge of sternomastoid. This is the most commonly enlarged node in upper respiratory tract infections, especially following tonsillitis. The commonest mass in the neck is a lymph node following infection, especially in children. Tuberculosis and atypical mycobacterial infection should always be considered with persistent cervical lymphadenopathy. The diagnosis of a neck lump is partly suggested by the age of the patient (Box 20.11). Features that suggest malignancy are progressive enlargement, hardness, lack of tenderness, fixation to deep structures and size (a node more than 1 cm in diameter is more likely to be malignant). Ultrasound is a valuable investigation, particularly combined with fine needle aspiration cytology.

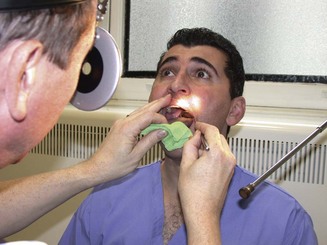

Examination of the mouth and throat

With practice it is possible to inspect all of the oral cavity, the pharynx and the larynx. Use a headlight or a head mirror to ensure adequate illumination and keep both hands free for the manipulation of instruments. First check the lips, teeth and gums, the floor of the mouth and the openings of the submandibular and parotid ducts. Observe the corners of the mouth for cracks or fissures (angular stomatitis or cheilitis). In children, this is usually due to bacterial infection, but poor dentition in the elderly leads to cracks and candidiasis (thrush). This may also be seen in severe iron-deficiency anaemia and in vitamin B2 (riboflavin) deficiency. Grouped vesicles on the lips on a red base with crusted lesions are seen in herpes simplex labialis. This viral infection is acute and the lack of induration and ulceration serves to distinguish it from malignancy. If salivary gland pathology is suspected, bimanual palpation, with one gloved finger in the mouth and synchronous palpation of the gland, may help to define pathology. Palpation is also valuable for examining the cheeks, tongue and even the tonsils on occasion. Tongue mobility (cranial nerve XII) should be assessed by protrusion and side-to-side movement. Look for wasting or fasciculation. Depress the tongue to inspect the tonsillar pillars, the palatine tonsils, soft palate and uvula. The tonsils and soft palate should be nearly symmetrical. Check the gag reflex (cranial nerve IX). The more distant portions of the pharynx can be inspected only with a laryngeal mirror or fibreoptic laryngoscope. For indirect laryngoscopy (Fig. 20.47), remove any dentures; gently hold the protruded tongue and ask the patient to take slow deep breaths. With the mouth opened wide, a warmed or demisted laryngeal mirror is introduced gently but firmly to the soft palate. Displace the soft palate upwards and backwards with the mirror and instruct the patient to say ‘ee’ or ‘ah’. The larynx elevates towards the examining mirror. The vallecula, epiglottis, supraglottis and glottis are examined in turn. The whole length of each vocal fold should be clearly visible and the mobility of each side noted. Vision can be helped in the gagging patient by using a 2% lidocaine anaesthetic spray. If an inadequate view is obtained (this depends upon the skill of the examiner), the flexible fibreoptic nasal endoscope (Fig. 20.48) allows a good view in almost every case. If available, the flexible endoscopic examination is mostly used due to the superior view, and recording the examination for clinical review. Videolaryngostroboscopy (Fig. 20.49) is a specialized endoscopic examination, useful for detailed visualization of the vocal folds. In this technique, stroboscopic light is used through the endoscope to visualize the mucosal wave of the vocal fold and heighten diagnostic capabilities.

Examination of the neck

This is part of the routine assessment of any patient with suspected or proven disease in the throat. The neck is exposed and inspected from the front and side before the examiner stands behind the patient (Fig. 20.50) and follows a well-rehearsed routine so that no area is missed. Start by palpating the nodes in the posterior auricular region, and then progressively feel for the nodes on the anterior border of the trapezius muscle down to the supraclavicular fossa. The latter area is palpated from behind forwards. The examining fingers then pass up the jugular vein, where the most important groups of nodes in the head and neck are situated, towards the ear. The jugular, parotid and preauricular areas are then examined, followed by submandibular and submental nodes. Finally, the nodes associated with the anterior jugular chain are examined. This brings the fingers to the thyroid gland (details of thyroid examination are in Ch. 16). Midline lumps should also be assessed with the patient protruding the tongue. Movement suggests attachment to the base of the tongue and implies the presence of a thyroglossal cyst (Fig. 20.51). The larynx should be mobile from side to side, and if the thyroid cartilage is held between thumb and first finger and gently moved against the cervical spine, it should grate. This laryngeal crepitus is a normal phenomenon. It may be reduced or abolished by hypopharyngeal pathology or a mass in the prevertebral space displacing the larynx away from the cervical spine. Finally, auscultate the carotid arteries and the thyroid gland.

Radiological examination

A soft-tissue lateral neck X-ray is not a sensitive investigation, even for detecting foreign bodies. A barium swallow is a dynamic investigation and can locate obstruction in the oesophagus or demonstrate incoordinate swallowing. It can be combined with video recording (videofluoroscopy). It is less helpful in evaluating the hypopharynx, where endoscopy under a general anaesthetic is the preferred investigation. Endoscopy is also helpful in taking biopsies in suspected malignancy. Ultrasound is useful for the evaluation of neck masses and the thyroid gland. Doppler ultrasound assesses the cervical vasculature. CT scanning helps to stage neoplastic disease and may demonstrate metastatic spread that has eluded palpation (Fig. 20.52). MRI complements CT as an imaging technique.