Ear, nose and throat emergencies

The ear

Anatomy of the ear

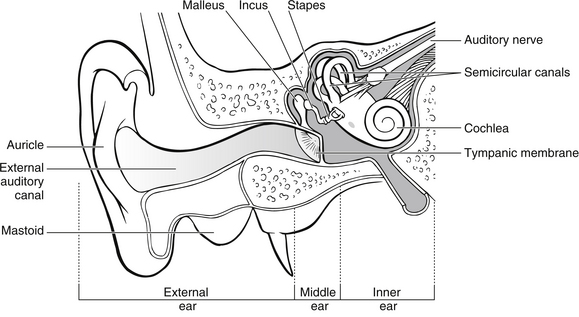

The ear is divided into three sections: external, middle and inner ear (Fig. 32.1). The outer ear funnels sound into the middle ear, which serves to transmit the sound to the auditory apparatus of the inner ear. The external ear consists of the auricle (or pinna), ear canal and tympanic membrane. The S-shaped ear canal is approximately 2.5–3 cm long and terminates at the tympanic membrane. The canal is lined with glands that secrete cerumen, a yellow waxy material that lubricates and protects the ear. Ear wax, sloughed off skin cells and dust may impair sound transmission through the outer ear, especially if a plug of wax attaches to the eardrum. The bone behind and below the ear canal is the mastoid part of the temporal bone. The lowest portion of this, the mastoid process, is palpable behind the lobule (Bickley & Szilagyi 2003).

Figure 32.1 Anatomy of the ear.

The tympanic membrane (or eardrum) is a thin, translucent, pearly grey oval disc separating the external ear from the middle ear. It can easily be observed with an otoscope. The tympanic membrane vibrates and moves in and out in response to sound. The middle ear is an air-filled cavity containing three tiny bones, the ossicles, which are individually called the malleus (hammer), the incus (anvil) and the stapes (stirrup), so named because of their appearance. The malleus is attached to the tympanic membrane by a set of ligaments. The incus is attached to the malleus and they move as one. The stapes attaches to the oval window, the membrane separating the middle and inner ear. When the tympanic membrane vibrates in response to sound, the malleus and incus are displaced, and the stapes vibrates against the oval window continuing the transmission of sound. The pharyngotympanic tube, formerly known as the Eustachian tube, which connects the middle ear with the nasopharynx, allows the passage of air to equalize pressure on either side of the tympanic membrane. The inner ear is composed of several fluid-filled chambers encased in a bony labyrinth in the temporal bone. The semicircular canals are also important for balance (Zemlin 2011).

Infections of the ear

Clinical evidence and management: Acute otitis externa is essentially a localized or diffuse infection of the lining of the external auditory meatus commonly associated with organisms such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus and occasionally fungi like Candida and Aspergillus (Sander 2001). Acute otitis externa frequently occurs following bathing or swimming because excessive moisture removes the protective cerumen from the ear canal allowing keratin debris to absorb water to create a nourishing environment for bacteria. For this reason it is often referred to as ‘swimmer’s ear’. Infection may be diffuse within the external auditory meatus or it may be focal in the form of a local swelling known as a furuncle, which may be extremely painful. Taking swabs for microbiological studies may not be well tolerated by the patient. It is essential that careful preparation of the patient takes place before any attempt is made to take a swab, especially if the individual is a child. Attempts to take a swab from an uncooperative child should be avoided as there is a risk that the tympanic membrane may be perforated by the swab if the child moves her/his head.

Treatment is based upon cleaning and drying the external auditory meatus. This should only be done after examination of the ear canal to determine the integrity of the tympanic membrane. Following cleansing of the external auditory meatus, topical medication containing steroids and antibiotics is necessary (Abelardo et al. 2007). Acute otitis externa largely results from identifiable causes and therefore lends itself to prevention strategies. The focus of much of the nursing care may revolve around educating the patient on keeping ears dry and on how to instill their prescribed medication.

Acute otitis media

Clinical evidence and management: Acute otitis media is often associated with systemic illness and fever, which may be attributed to the otitis media alone or occur in conjunction with coincidental upper respiratory tract infection (Ludman 2007). Acute otitis media is characterized by rapid onset of ear pain, headache, tinnitus, hearing loss, and nausea or vomiting. Infants and young children may present with irritability, crying, rubbing or pulling the ear, restless sleep and lethargy (Olson 2003). Children are often prone to acute otitis, with up to 30 % of those presenting with otitis media being children under three years of age, as the infection frequently results from upper respiratory tract infection of bacterial or viral origin.

Antibiotics are not often necessary in the treatment of uncomplicated otitis media with the mainstay of treatment being analgesia with antipyretic properties. Antibiotics in otitis media provide a modest benefit that must be balanced against the risk of adverse effects (Coker et al. 2010). In most cases involving children, antibiotics only provide symptomatic benefits after the first 24 hours, at which time symptoms are generally resolving. Serious complications, such as meningitis, mastoiditis, intracranial abscess, permanent hearing loss and neck abscess can develop as a result of otitis media (Olson 2003).

If the tympanic membrane has perforated, it is often the painful result of otitis media, trauma or foreign body insertion and is associated with loss of hearing. The individual should be advised to keep the ear dry and prevent water entering the ear. However, the ear should not be packed, and the patient should be advised not to do this at home, as it may prevent the discharge draining from the ear. More than 90% of tympanic membrane perforations heal spontaneously and management includes antibiotics, analgesia and antipyretics (Olson 2003). In some cases, where the tympanic membrane is intact, the infective material may cause the membrane to bulge, which also causes pain and loss of hearing. In such cases, admission to hospital is required in order that the tympanic membrane may be surgically perforated under general anaesthetic and grommets inserted to allow the discharge to drain out freely.

Mechanical obstruction

Clinical evidence and management: Cerumen may build up in the external auditory meatus, causing mechanical obstruction, which may be exacerbated by cleaning the ear with cotton-tipped buds. Such activities often cause cerumen to be pushed deep into the canal, causing impaction against the tympanic membrane. Obstruction in either case may cause a reduction in hearing, but rarely causes complete deafness. Impacted cerumen is often hard and resistant to removal by syringing alone; thus, in the ED the most appropriate management is to initiate a regimen to soften the cerumen using commercially available eardrops.

Foreign bodies

Clinical evidence: Older children and adults may present with a history of having a foreign body in the ear. Young children have a tendency to put foreign bodies in their ears, but as they often do not disclose this information, the nurse should be suspicious of children who present with earache, hearing loss and discharge from the ear. Small insects may also crawl into the ear canal and become trapped, causing a great deal of discomfort if still alive and buzzing.

Management: Foreign bodies may be removed using a variety of techniques including irrigation, suction and instrumentation, by individuals with the appropriate skills (Davies & Benger 2000). Care should be taken to ensure that this process does not impact the foreign body further in the ear, causing trauma to the external auditory meatus and the tympanic membrane.

Severe pain and distress are caused to patients when live insects enter the ear and they need to be killed in situ by the instillation of oil or lignocaine prior to removal (Davies & Benger 2000). Analgesic and/or antibiotic treatments should be prescribed as necessary.

Direct trauma

This is commonly caused by the insertion of objects either to clean the ear or to relieve itching, although any object inserted into the external auditory meatus has the potential to cause tympanic perforation. Objects frequently used are cotton-tipped buds and hair grips. In most cases, the ruptured tympanic membrane will heal spontaneously in 1–3 months (Bluestone 2007); however, ENT opinion should be sought. Pain relief and prophylactic antibiotics may be required, especially if the mechanism of injury includes contamination by water or a foreign body.

Indirect trauma

Perforation of the tympanic membrane may be caused by high pressure transmitted along the external auditory meatus to the tympanic membrane. This barotrauma to the tympanic membrane results from significant changes in atmospheric pressure causing air trapped in the external ear canal or behind the tympanic membrane to expand or contract enough to rupture the eardrum. This pressure may be generated by such forces as a slap to the ear, flying, diving or exposure to an explosion. Pressures of as little as 35 kPa on the tympanic membrane may cause it to rupture, although in the explosion scenario some individuals will be protected from these pressures because of the orientation of the external auditory meatus to the blast wave (Garner 2011). As it is unlikely that data will be available regarding blast wave pressure, all individuals who have been in close proximity to an explosion should be carefully assessed and referred to the ENT department if appropriate.

External trauma

Wounds to the external ear or pinna in most cases may be closed by conventional wound closure methods. However, if the cartilage of the pinna is involved, scrupulous wound cleansing is required, as any subsequent infection is likely to lead to permanent deformity of the pinna. All wounds require antibiotic cover, such as amoxiclav (Corbridge & Steventon 2010).

Blunt trauma to the pinna, commonly occurring in contact sports, may result in haematoma formation. The haematoma, if untreated, may lead to the necrosis of the underlying cartilaginous skeleton of the pinna. O’Donoghue et al. (1992) advocate early incision and drainage as the most appropriate course of action in order to reduce morbidity. This is likely to require a general anaesthetic, and therefore referral to the ENT department is pertinent.

There is an increasing trend of cosmetic piercings of the upper one third of the pinna that puncture the cartilage. Hanif et al. (2001) report how infections following such piercings can result in auricular perichondritis.

The nose

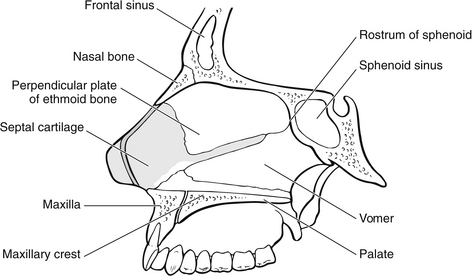

The nose is a structure with a bony and cartilaginous skeleton that is attached to the skull via the frontal bone and the maxilla. It is a vascular structure whose prime functions are to interface with the respiratory system, to warm, filter and moisten inhaled air and to act as a sense organ involved in the enjoyment of food and the detection of danger in the case of smoke and gas. The upper third of the nose, where the frontal and maxillary bones form the bridge, is bony (Fig. 32.2).

Figure 32.2 Anatomy of the nose.

Foreign bodies

Clinical evidence and management: Usually the child will have told the parents that she/he has put something up her/his nose, or the parents will have noticed that the child has a purulent discharge from one nostril. Unilateral discharge is highly suggestive of a foreign body in the nose; however, children are not averse to placing foreign bodies in each nostril, resulting in a bilateral discharge.

The removal of a foreign body in the nose follows the same rules as the removal of a foreign body in the ear. The child should be seated in a dental chair or on a parent’s lap in a semi-recumbent position. Initial assessment and history should ascertain the type of foreign body present, how long it has been in the nostril and whether there has been any bleeding or discharge. Careful explanation and instruction regarding the procedure for removal are required and psychological support for both parents and child is essential both for humanitarian reasons and to gain their cooperation during the procedure. Removal can be attempted using some topical anaesthetic spray, a ring curette or alligator forceps (Olson 2003). Care should be taken to prevent damage to the highly vascular nasal septum and mucosa during removal of a nasal foreign body. If the child is too distressed, the foreign body is too far into the nostril or there is any evidence of trauma to the nostril already, then the child should be referred to the ENT surgeon (Reynolds 2004).

Epistaxis

Epistaxis is often seen as a relatively minor problem in the ED. However, something as simple as a nose bleed can quickly turn into a life-threatening condition if it is not treated swiftly and correctly. Epistaxis can occur from either local or systemic causes including direct trauma, nose picking, inflammatory disease involving the nasal mucosa, coagulation deficits (including medication) and hypertension (Castelnuovo et al. 2010).

Clinical evidence and management: The patient will present with active bleeding from the nose, or a recent history of bleeding that may have stopped. The main aim of treatment is to stop the epistaxis. If the bleeding is from the anterior end of the septum (Littles’ area), bleeding can usually be alleviated by seating the patient upright and advising her to hold the front soft part of the nose very firmly (Reynolds 2004). The patient’s head should be tilted forward over a bowl.

Once active haemorrhage is controlled, any precipitating medical factors should be identified and corrected if clinically safe to do so. The anticoagulated patient can pose a challenging problem, because they tend to have more severe epistaxis and bleed from several sites. Because of the risk for serious medical complications, reversal or discontinuation of the anticoagulation medication should not be performed unless it is deemed safe by the initiating medical specialty. During warfarin-related epistaxis, 80 % of patients were outside their disease-specific international normalized ratio (INR) range; therefore, in addition to a complete blood count, all patients should have an INR evaluated at the time of presentation (Smith et al. 2011, Rudmik & Smith 2012). If the patient is hypertensive on presentation an antihypertensive agent, such as nifedipine, may need to be administered.

Occasionally, the patient with an epistaxis may need resuscitative care due to blood loss. The siting of a large-bore intravenous line and commencement of replacement fluid, monitoring of vital signs, and taking of blood for a full blood count and cross-match are necessary in this case. All patients with epistaxis have the potential to become shocked if bleeding is not stopped. Initial assessment involves an estimate of the amount of bleeding, the length of time active bleeding has been taking place and any previous relevant medical history. Physical assessment of the patient should always include monitoring of vital signs (Melia & McGarry 2011).

Nasal fracture

This is the most common facial fracture accounting for almost 60 % of all facial fractures (Allareddy & Nalliah 2011). It usually caused by blunt trauma and commonly seen in the ED patient who has been assaulted. Clinically, the injury can usually be recognized immediately afterwards by the distortion from normal shape, although this soon becomes obscured by soft tissue swelling.

Clinical evidence and management: There will be a history of trauma to the nose, swelling deformity and occasionally epistaxis. It is important to examine the nose for any evidence of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), rhinorrhoea and any indication of fractures to the cribiform plate. Normal CSF is clear and slightly yellow, but CSF nasal drainage is frequently mixed with blood. Gisness (2003) describes septal haematoma as a bulging, tense bluish mass that feels doughy when palpated. Septal haematomas should be urgently drained to prevent airway obstruction and necrosis of the septal cartilage. Septal haematoma may strip the septal cartilage of blood supply and progress to abscess formation or later cartilage necrosis, resulting in significant nasal deformity and septal perforation. An overlooked septal haematoma may critically disfigure the patient and it should always be ruled out (Lynham et al. 2012).

Generally, little can be done for patients following a fracture of the nose until 5–10 days after the initial injury, due to soft tissue swelling. The patient should therefore be referred to the ENT outpatients department. Since the nasal bones will become firmly set within 3 weeks of the injury, reduction of a nasal fracture is indicated in any patient with significant cosmetic deformity or functional compromise (Vats et al. 2007). X-rays are often requested for medico-legal reasons, but are not strictly necessary (see also Chapter 10).

Rhinorrhoea

Clinical evidence and management: The patient presents with a runny nose or the sensation of something dripping down the back of the throat. The discharge may be clear or purulent. The causes are:

The patient may need to have a foreign body removed. If an allergy is suspected, antihistamines may be prescribed, and advice should be given on avoidance of common allergens, i.e., grass/tree pollen, dust and cat or dog fur. The patient may also need to be referred to an allergy clinic. Infective rhinosinusitus may need treatment with antibiotics. If a tumour is suspected, urgent referral to ENT will be necessary.

Allergic rhinitis

This can be seasonal or perennial. The symptoms are those of sneezing, nasal obstruction and rhinorrhoea. There is often itching of the nose, eyes and palate, accompanied by loss of smell, rhinorrhoea and episodes of sneezing. Secondary symptoms such as headache and facial pain may also occur due to nasal congestion (Stearn 2005). Evidence of associated allergic diseases, such as asthma and eczema, should also be sought as there is a high correlation between the conditions. Bousquet et al. (2001) note that some 80 % of asthma patients also suffer from allergic rhinitis. Patients should be advised to avoid common allergens as much as possible, such as grass/tree pollen, cat or dog fur and house dust, especially in the early morning and later afternoon/early evening when pollen counts are at their highest. Wearing sunglasses, spectacles or contact lenses (if appropriate) may also be beneficial in reducing eye symptoms. Patients should be given antihistamines and advised to see their GP for further prescription of any topical decongestants and for referral to a local allergy clinic.

Sinusitis

Sinusitis is an inflammatory, and usually infective, condition of the paranasal sinus, which is associated with approximately 90 % of viral infections of the upper respiratory tract. Complications of untreated or inadequately treated acute sinusitis include chronic sinusitis, orbital abscess, meningitis, brain abscess, cavernous sinus thrombosis and osteomyelitis of the maxillary or frontal bones (Olson 2003, Kumar 2004).

Clinical evidence and management: The main symptoms a patient can present to the ED are sneezing, headache and facial pain which are worse when bending forward, and a recent history of upper respiratory tract infection. Maxillary toothache without obvious dental cause may also occur. The patient may be very worried about the severity of their headache. A set of baseline observations of pulse, blood pressure, temperature and respirations will aid diagnosis. This, along with a clinical history, may help to rule out other diagnoses such as hypertension or subarachnoid haemorrhage.

Treatment usually involves prescription of a broad-spectrum antibiotic. Advice can be given to take analgesia and to use a decongestant spray. The patient should be advised to see their GP if symptoms persist, as referral to the ENT department may be necessary. Complications of sinus disease include meningitis, orbital extension and brain abscess (Kumar 2004).

The throat

The throat, or pharynx, consists of the nasopharynx, oropharynx and laryngopharynx. It is a funnel-shaped tube that starts at the internal nares (nasal passages) and extends to the level of the cricoid cartilage. Its wall is composed of skeletal muscles and lined with mucous membrane. The central portion (oropharynx) provides a common passage for air, drink and food (Bickley & Szilagyi 2003). Pharyngeal constrictor muscles propel food or liquid into the oesophagus. These muscles are also responsible for the gag reflex, which is controlled by the cranial nerves. The larynx helps to prevent aspiration, assists in coughing and serves as the organ for speech.

Airway obstruction

Many patients who attend the ED with either an apparently trivial throat condition or more severe conditions are potentially at risk of airway obstruction. Thus the potential for a life-threatening condition to be overlooked is ever-present, unless there is a high index of suspicion and a rigorous assessment of these patients takes place (see also Chapter 2).

Should the airway become compromised, by whatever means, patency must be achieved as a matter of urgency, in order for ventilation to occur. Airway management should initially be in the form of basic techniques, such as positioning the patient and the Heimlich manoeuvre where the obstruction is caused by a foreign body. The Heimlich manoeuvre is not recommended for infants because of poor protection of the upper abdominal organs (International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation 2006).

Oral cavity

Trauma to the oral cavity can cause a great deal of tissue swelling. Extensive bleeding can occur because of the vascular nature of the region, which is why lacerations to the tongue can bleed dramatically. Teeth can be dislodged or broken and inhalation can occur. Fracture of the mandible may also cause problems and these are dealt with in Chapter 10. Injuries to the oral cavity are common in young children (Zimmermann et al. 2006).

Infective

Infections of the oral cavity most commonly involve the teeth and gums and referral to a dentist may be the most appropriate action.

Clinical evidence and management: Abscesses of the teeth may need drainage and/or antibiotic therapy, which is most appropriately carried out by a dental practitioner. Frequently the most appropriate course of action is to refer the patient to their GP, but in the interim the patient may be prescribed antibiotics and analgesia. Patient education may focus upon the safe and efficacious use of prescribed medication and the initiation of oral hygiene measures including saline mouthwashes and tooth brushing.

Reactive

Aetiology of anaphylactic shock: Anaphylaxis is a severe, life-threatening, generalized or systemic hypersensitivity reaction. It is characterized by rapidly developing life-threatening airway and/or breathing and/or circulation problems usually associated with skin and/or mucosal changes. The incidence of anaphylaxis appears to be increasing, in part given the possibility of omission of a precise diagnosis for a patient (Simons & Sampson 2008, Younker & Soar 2011). It generally follows from exposure to a foreign protein to which the patient has been previously sensitized. The individual becomes sensitized to the allergen by the production of antibodies in response to this exposure. These bind to basophils in the blood and sensitize the cells. Common sensitizing substances are antibiotic medication, especially penicillin and penicillin derivatives, bee stings, foodstuffs such as peanuts and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications. When the allergen re-enters the body, this stimulates the release of mediators of anaphylaxis, e.g., histamine, serotonin, slow-release substances of anaphylaxis (SRS-A) and platelet-activating factors (PAF), which result in cellular damage.

Clinical evidence of anaphylactic shock: Anaphylaxis is likely when all of the following three criteria are met:

• sudden onset and rapid progression of symptoms

• life-threatening airway and/or breathing and/or circulation problems

• skin and/or mucosal changes (flushing, urticaria, angioedema) (Younker & Soar 2011).

Physiological changes include:

• increased blood capillary permeability – causing localized oedema

These changes may result in some or all of the following symptoms:

Symptoms can occur within minutes of ingestion, with the allergen gaining rapid access to the circulatory system through the digestive tract and activating mast cells in the mouth, throat, lungs, skin, abdomen and other tissues and organs (Crusher 2004). Management is based on positioning of the patient in the supine position and the administration of adrenaline (epinephrine) via the intramuscular route. This is supported with high-flow oxygen to combat potential hypoxia. Where adrenaline is administered, the patient should be admitted for a period of observation. If possible, the allergen should be identified to enable the patient to avoid this in the future.

Pharynx

Traumatic

Clinical evidence: External as well as internal trauma may cause oedema in this region. People who have attempted suicide by hanging or strangulation and those involved in accidents involving strictures around the neck account for a proportion of this group of patients. In cases of strangulation and hanging where the patient is unable to self-advocate, for whatever reason, consideration should be given to any medico-legal implications, and where appropriate the police may need to be informed. Victims of road traffic accidents may also suffer trauma to this region of the body which can be easily overlooked in the presence of more obvious injuries, highlighting the importance of thorough primary and secondary surveys. Where neck injuries are apparent, the possibility of trauma to the internal structures should be considered.

Management: The airway is the number one priority. Careful and accurate assessment of the patient and the extent of injuries must be carried out early. If the patient is conscious, a history of the event and mechanism of injury will give an indication of the stresses involved. Signs of airway obstruction such as noisy breathing should be noted and monitored for deterioration. Admission is essential where there is a degree of swelling which is likely to increase, leading to the airway becoming compromised.

Infective

Clinical evidence: There will be a number of patients attending the ED with simple sore throats. They often only need reassurance and simple advice, possibly with referral to their GP if symptoms persist. There will be some adults among them with a peritonsillar abscess that will require further intervention. Children are less likely to complain of a sore throat but often go off their food and generally feel unwell and are pyrexial. These children may present with dysphagia, a wheeze or stridor and will need careful assessment. The possible cause of these symptoms is epiglottitis, which is a potentially fatal inflammation of the epiglottis and pharynx as a result of infection. McEwan et al. (2003) report an age range of presentation between 6 months and a little over 10 years.

Management: Peritonsillar abscesses in need of drainage will require the attention of the ENT team. The patient should be referred as soon as the diagnosis has been made. As a general anaesthetic may be required, the patient should be kept nil by mouth, and unnecessary examination of the throat should be avoided as this is likely to be very uncomfortable.

References

Abelardo, E., Pope, L., Rajkumar, K., et al. A double-blind randomised clinical trial of the treatment of otitis externa using topical steroid alone versus topical steroid–antibiotic therapy. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 2007;266(1):41–45.

Allareddy, V., Nalliah, R.P. Epidemiology of facial fracture injuries. Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery. 2011;69:2613–2618.

Bickley, L.S., Szilagyi, P.G. Bates’ Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking, eighth ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2003.

Bluestone, C., Klein, J. Otitis Media in Infants and Children. Hamilton: BC Decker Inc; 2007.

Bousquet, J., van Cauwenberge, P., Khaltaev, N. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2001;108(5):S147–S333.

Castelnuovo, P., Pistochini, A., Palma, P. Epistaxis. Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck. European Manual of Medicine, Part. 2010;2:205–208.

Coker, R., Chan, L., Newberry, S., et al. Diagnosis, microbial epidemiology, and antibiotic treatment of acute otitis media in children. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;304(19):2161–2169.

Corbridge, R., Steventon, N. Oxford Handbook of ENT and Head and Neck Surgery. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010.

Crusher, R. Anaphylaxis. Emergency Nurse. 2004;12(3):24–31.

Davies, P., Benger, J. Foreign bodies in the nose and ear: a review of techniques for removal in the emergency department. Journal of Accident and Emergency Medicine. 2000;17:91–94.

Garner, J. Ballistic and blast injuries. In: Smith J., Greaves I., Porter K., eds. Oxford Desk Reference: Major Trauma. Oxford: Oxford Medical Publications, 2011.

Gisness, C. Maxillofacial trauma. In Newberry L., ed.: Sheehy’s Emergency Nursing: Principles and Practice, fifth ed, St Louis: Mosby, 2003.

Hanif, J., Frosh, A., Marnane, C., et al. High ear piercing and the raising incidence of perichondritis of the pinna. British Medical Journal. 2001;322:906–907.

International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. The International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) consensus on science with treatment recommendations for pediatric and neonatal patients: Pediatric basic and advanced life support. Paediatrics. 2006;117(5):e955–e977.

Kumar, S. Ear, nose and throat. In Cameron P., Jelinek G., Kelly A.M., Murray L., Brown A.F.T., Heyworth J., eds.: Textbook of Emergency Medicine, second ed, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2004.

Ludman, H. Pain in the ear. In Ludman H., Bradley P.J., eds.: ABC of Ear, Nose and Throat, fifth ed, London: Blackwell Publishing/BMJ Books, 2007.

Lynham, A., Tuckett, J., Warnke, P. Maxillofacial trauma. Australian Family Physician. 2012;41(4):172–180.

McEwan, J., Giridaran, W., Clarke, R., et al. Paediatric acute epiglottitis: not a disappearing entity. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2003;67:317–321.

Melia, L., McGarry, G.W. Epistaxis: update on management. Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head & Neck Surgery. 2011;19(1):30–35.

O’Donoghue, G.M., Bates, G.J., Narula, A.A. Clinical ENT: An Illustrated Textbook. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1992.

Olson, C. Dental, ear, nose and throat emergencies. In Newberry L., ed.: Sheehy’s Emergency Nursing: Principles and Practice, fifth ed, St Louis: Mosby, 2003.

Reynolds, T. Ear, nose and throat problems in Accident and Emergency. Nursing Standard. 2004;18(26):47–53.

Rudmik, L., Smith, T. Management of intractable spontaneous epistaxis. American Journal of Rhinology & Allergy. 2012;26(1):55–60.

Sander, R. Otitis externa: A practical guide to treatment and prevention. American Family Physician. 2001;63(5):927–937.

Simons, F.E., Sampson, H.A. Anaphylaxis epidemic: fact or fiction? Journal of Allergy & Clinical Immunology. 2008;122:1166–1168.

Smith, J., Siddiq, S., Dyer, C., et al. Epistaxis in patients taking oral anticoagulant and antiplatelet medication: Prospective cohort study. Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 2011;125(1):38–42.

Stearn, R. One airway, one disease. Primary Health Care. 2005;15(2):31–34.

Vats, A., Narula, A., Bradley, P.J. Trauma, injuries and foreign bodies. In Ludman H., Bradley P.J., eds.: ABC of Ear, Nose and Throat, fifth ed, London: Blackwell Publishing/BMJ Books, 2007.

Younker, J., Soar, J. Recognition and treatment of anaphylaxis. Nursing in Critical Care. 2011;15(2):94–98.

Zemlin, W.R. Speech and Hearing Science: Anatomy and Physiology, fourth ed. Boston: Allan and Bacon; 2011.

Zimmermann, C.E., Troulis, M.J., Kaban, L.B. Pediatric facial fractures: Recent advances in prevention, diagnosis and management. International Journal of Oral Maxillofacial Surgery. 2006;35(1):2–13.