Chapter 2 Ear, nose and throat and head and neck problems

2.1 Introduction

The specialty of ear, nose and throat — head and neck (ENT — head and neck) surgery is very broad and complex. Each component is a subspecialty in itself. Addressing any problems relating to the head and neck with this in mind will allow you to systematically approach the patient’s problem. As in any aspect of clinical medicine, the initial diagnosis is made by taking a thorough history prior to a complete physical examination that is supplemented by special investigations.

History

When a patient presents with any of these symptoms (Table 2.1) it is important to characterise the symptoms in terms of site, severity, radiation, frequency, duration, exacerbating and relieving factors, associated features, the progression of symptoms and how it affects the patient’s activities of daily living. When taking a history, the past history needs to be noted, including previous surgery to the respective parts of the ear, nose and throat, head and neck and any associated conditions. A patient’s medication and adverse reactions to medication should be known, as well as their social history, including their smoking and alcohol consumption and environmental exposures such as noise, dust and any other potential allergens. The family history should be known and it is also wise to find out about any family tendencies regarding bleeding disorders and deafness.

| Ear | Otalgia, hearing loss, vertigo, tinnitus, aural fullness, discharge, hissing, facial weakness, bleeding, blockage |

| Nose and sinuses | Epistaxis, obstruction, hyposmia/anosmia, loss of taste, facial pain, post-nasal drip, facial asymmetry, diplopia, epiphora, red eye, nasal discharge, allergy/sneezing/hay fever |

| Throat | Pain, dysphagia, dysphonia, reflux, globus, referred pain, cough, haemoptysis, shortness of breath, snoring, drooling |

| Head and neck: lump, pain |

Examination of the head and neck

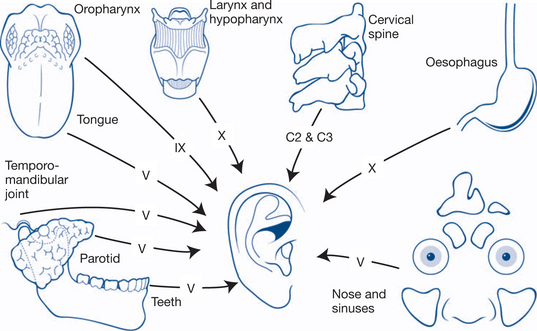

As stated, a systematic approach to examining the head should recognise the principles of ENT — head and neck and include this in the examination, along with the cranial nerves. This will make a complete examination of the area. It is important to be aware of referred pain (Fig 2.1); for example, the ear is supplied by multiple nerves and ear pain can present as referred pain from intraoral or laryngeal pathology. Look for signs of redness, swelling, tenderness, increased warmth and loss of function.

Throat

Hypopharynx

The hypopharynx and larynx are examined with a large mirror and head light as is the tongue base. Laryngeal assessment includes the epiglottis, vallecula, aryepiglottic fold, arytenoids, false cords, laryngeal ventricles, true cords, the subglottis and trachea. Reflux can often be detected by visualising reddening of the posterior glottis and arytenoids.

Head and neck lumps

Colour, contour, cough, compressibility

Fluctuance, fixation, fluid, filling and emptying

Temperature, transillumination, thrill, tenderness

Local features, lobulation, lymph nodes, lumps elsewhere.

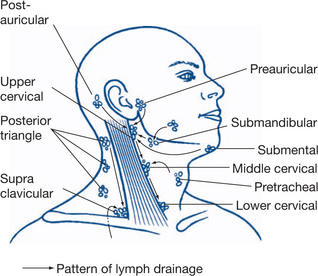

Palpation of the head and neck involves palpation of the lymph nodes and the thyroid gland. It is important to palpate one side of the head and neck at a time and systematically approach all the groups of lymph nodes (Fig 2.2). Deep palpation of the jugular chain is important because these glands are deep to sternocleidomastoid. One should take care when compressing around the carotid.

Table 2.2 outlines the process for performing a thyroid examination when thyroid disease is detected or suspected. Table 2.3 outlines an examination of the cranial nerves.

Table 2.2 Thyroid examination — performed if thyroid disease is detected or suspected

| Look | Patient — hyper/hypothyroid, thyroid eye signs, proptosis — Graves’ disease, lid lag, chemosis a complication, voice — recurrent laryngeal nerve compression, goitre |

| Feel | Right versus left side, prominent nodules |

| Percuss — retrosternal extension | |

| Auscultate — bruits | |

| Pemberton’s sign — a sign of SVC compression — raise arms above head and look for venous congestion in the head | |

| Periphery | Pulse, reflexes |

Table 2.3 Screening examination of the cranial nerves

| I | Smell |

| II | Visual acuity, light reflex — direct and consensual, fields |

| III/IV/VI | Eye movements |

| V — V1, V2, V3 | Sensation, motor — palpate jaw (masseter, temporalis) |

| VII | Facial movements: temporal — forehead; zygomatic — eye closure; buccal — cheek; marginal mandibular — lower lip; cervical — platysma |

| VIII | Tuning fork |

| IX/X | Gag reflex |

| XI | Sternocleidomastoid, trapezius — palpate |

| XII | Tongue mobility; palsy indicated by protrusion to affected side |

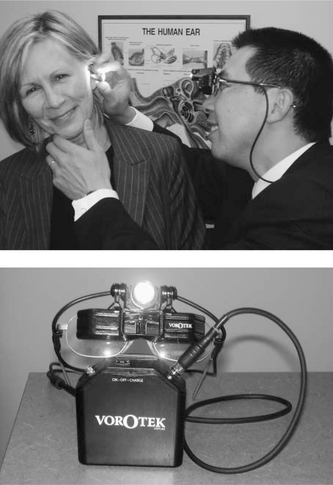

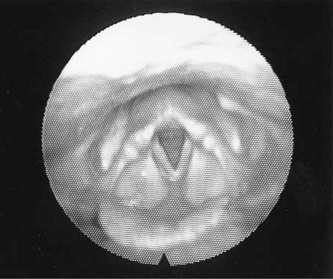

The voroscope (Fig 2.3) has revolutionised the ENT — head and neck examination. A good headlight from theatre will often suffice. Sometimes only a light source and head mirror are available.

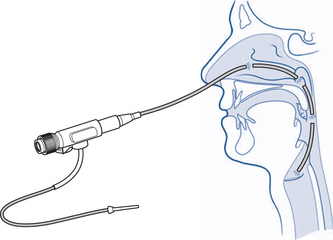

Flexible nasal endoscopy has also revolutionised the diagnosis of ENT — head and neck conditions. It has become an integral part of the examination and enabled office-based diagnosis. There are many hidden areas in ENT — head and neck examination and the nasoendoscope has permitted access to the internal nose, sinus outflow tracts, post-nasal space, larynx, hypopharynx, tongue base and sometimes the proximal oesophagus (Fig 2.4).

Infective: may involve bacterial, viral, fungal and parasitic problems

Tumour: subdivided into benign and malignant

Metabolic causes such as diabetes and renal impairment

Investigations are ordered to:

The common investigations include:

The last four investigations are usually ordered by ENT — head and neck specialists.

2.2 Ear

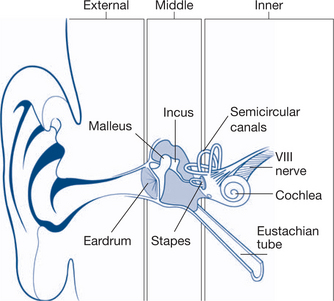

The ear has three components consisting of a number of parts listed in Table 2.4.

| Outer ear | Pinna — parts |

| External auditory canal — lined by skin, acts to remove accumulated squames from the tympanic membrane out of canal | |

| Tympanic membrane | |

| Middle ear | Ossicles: malleus (hammer)/incus (anvil)/stapes (stirrup) — act as the chain between the tympanic membrane and the oval window membrane |

| Eustachian tube — functions to aerate middle ear | |

| Middle ear mucosa — respiratory type | |

| Mastoid cells — part of the temporal bone and joined to middle ear cleft | |

| Inner ear | Cochlea and vestibular apparatus |

| Oval window — superior — part of the cochlear connection to ossicular chain | |

| Round window — inferior — part of the cochlea that moves in response to any hydraulic force placed on the oval window |

To examine an ear, systematically investigate the outer ear followed by the middle ear and then the inner ear (Fig 2.5).

For the outer ear look at the normal contour of the outer ear, the ear canal and the tympanic membrane. Sometimes it is necessary to remove the wax from the canal to get a good view. When assessing the middle ear also assess for tympanic membrane mobility using what is called pneumatic otoscopy. Check any perforation of the tympanic membrane by assessing its size, the site, associated discharge and the condition of the middle ear mucosa. The tests of the inner ear that are commonly performed are: using a 512 Hz tuning fork; testing a patient’s gait; and performing a Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre. Prior to performing a Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre the stethoscope should be used to listen for any carotid bruits because the Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre may precipitate a TIA. The stethoscope is also used to listen for pulsatile tinnitus and is placed on the mastoid tip. The Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre is diagnostic of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) and is performed on an examination couch. While sitting up, the patient turns their head quickly to one side while keeping the eyes wide open and focusing on a spot in the distance in the line of their eye sockets. Next, the patient lies back with their head dependent over the head of the examination bench. The examiner inspects for nystagmus, which indicates an overstimulated semicircular canal system. It is a positive result when nystagmus is elicited on the side to which the head is turned.

External ear

Wax and otitis externa

Predisposing factors include the following.

The build-up of debris is subsequently infected by bacteria or fungi.

The most common bacteria is Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Fungal hyphae are seen in fungal infections.

Management

OE is best managed with one or more of the following measures:

Middle ear

Otitis media

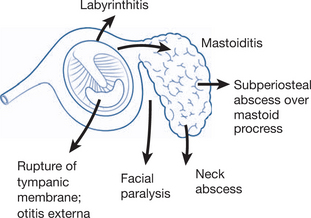

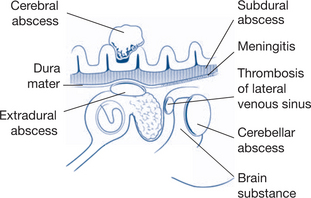

Otitis media is an inflammation of the middle ear/mastoid cavity. Its underlying cause is an abnormality of the Eustachian tube that ceases to aerate the middle ear, leading to a range of possible complications (Figs 2.6 and 2.7). A negative pressure forms in the cleft and an effusion results. There are many causes of a dysfunctional Eustachian tube. In children, the Eustachian tube is shorter and more horizontal, therefore, more prone to blocking. Causes include: viral URTI, cleft palate and a post-nasal space tumour. The effusion may become secondarily infected resulting in acute otitis media (AOM). Common organisms are: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella.

Complications of AOM are those resulting from mastoiditis and include:

A chronic discharging ear for more than three months is termed chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM). It results from chronic infection, with an associated biofilm formation or may be caused by a cholesteatoma.

Inner ear

Hearing loss

There are many causes of hearing loss, as indicated in Table 2.5.

| Cause | Conductive hearing loss | Sensorineural hearing loss |

|---|---|---|

| Congenital | Atresia of ear, ossicular abnormalities | Prenatal: genetic, rubella |

| Acquired | External: wax, otitis externa, foreign body | Perinatal: hypoxia, jaundice |

| Middle ear: middle ear effusion, chronic suppurative otitis media, cholesteatoma, | Trauma: noise, head injury, surgery | |

| Perforated drum, otosclerosis, traumatic perforation of drum | Inflammatory: chronic otitis, meningitis, measles, mumps, syphilis | |

| Ossicular disruption | Degenerative: presbyacusis | |

| Ototoxicity: aminoglycosides, cytotoxics | ||

| Neoplastic: acoustic neuroma | ||

| Idiopathic: Ménière’s disease, sudden deafness |

Based on Dhillon & East 2006

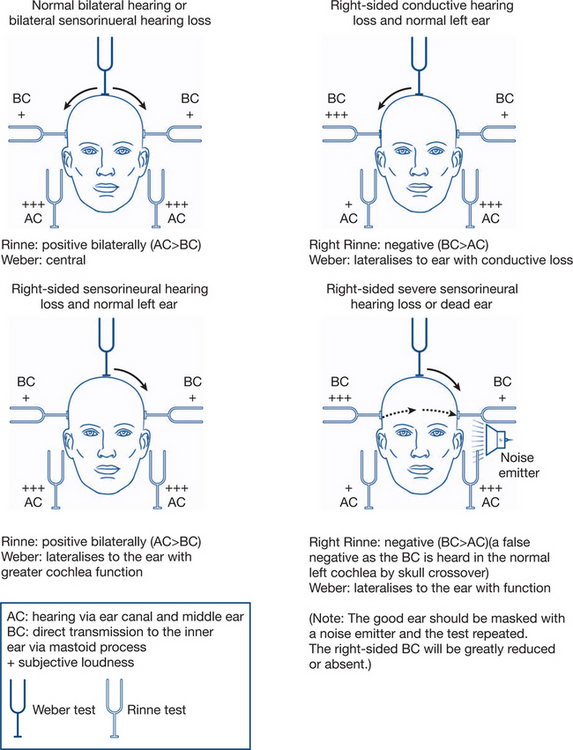

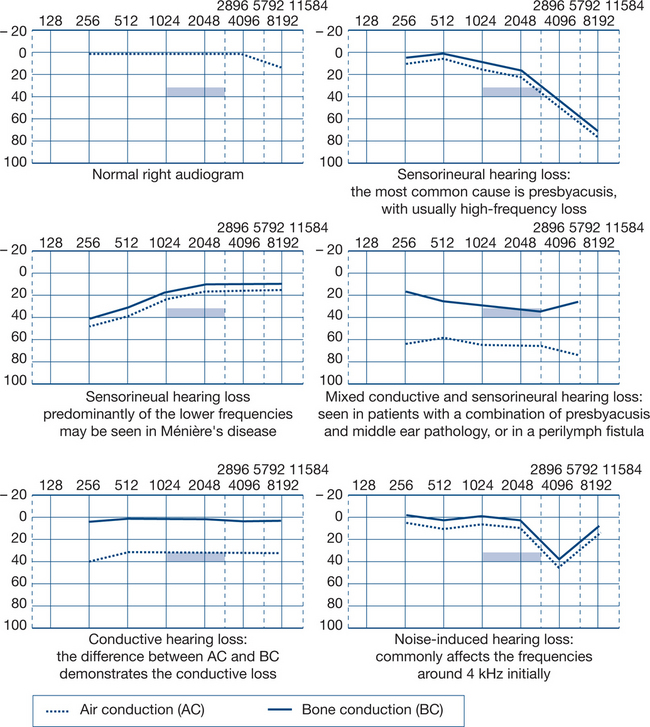

A complete examination with tuning fork tests is required and an audiogram will guide the diagnosis (Figs 2.8a and b).

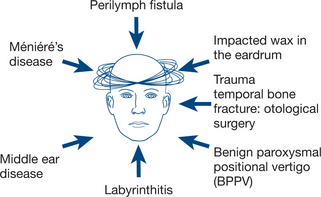

Vertigo

Vertigo can be disabling. The vestibular apparatus may be overactive or underactive. An imbalance between the left and right sides may result in vertigo. There are many causes (Fig 2.9).

The most common causes of vertigo are:

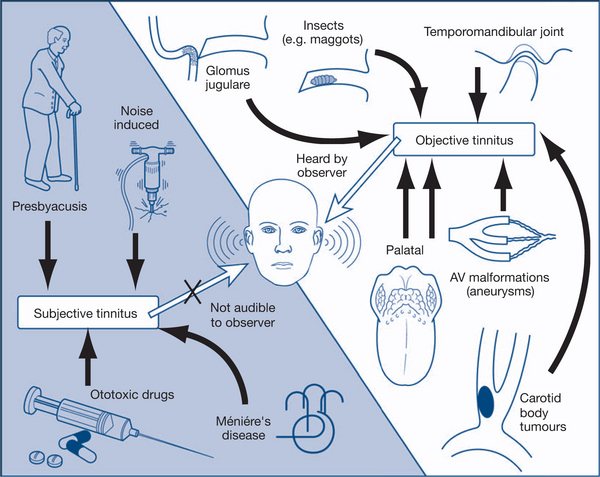

Tinnitus

Defined loosely as noise generated somewhere in the head, tinnitus (Fig 2.10) is annoying to the patient and can be extremely disabling.

There are many causes for tinnitus, but the most common is idiopathic.

Reversible causes, such as outer, middle or inner ear pathology, need to be ruled out. An audiogram is a good screening test. CT and MRI may be ordered.

2.3 Facial weakness

Table 2.6 lists the most common causes of facial weakness.

| Site | Aetiology |

|---|---|

| Intracranial | Acoustic neuroma |

| CVA* | |

| Brain stem tumour* | |

| Intratemporal | Bell’s palsy |

| Herpes zoster oticus | |

| Middle ear infection | |

| Trauma | |

| – surgical | |

| – temporal bone fracture | |

| Extratemporal | Parotid tumours |

| Miscellaneous | Sarcoidosis, polyneuritis |

Based on Dhillon & East, 2006

Management

Trauma

There are many forms of trauma. Trauma to the ear may result in:

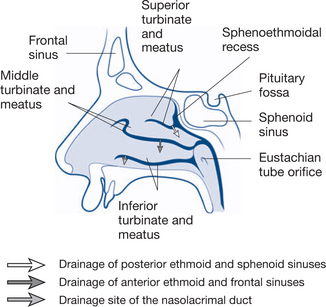

2.4 Nose and sinuses

Anatomy/physiology

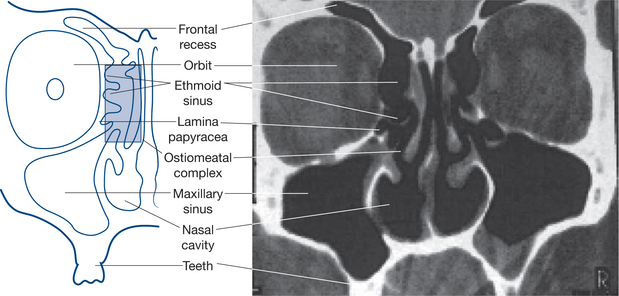

The nose and sinuses are made up of a number of components (Figs 2.11 and 2.12).

Nerve supply

Epistaxis

Most commonly epistaxis is anterior and unilateral (approximately 90%) from Little’s area. Posterior epistaxis is uncommon; it presents bilaterally and is often severe from the sphenopalatine artery.

Treating epistaxis is based on the following principles.

Nasal obstruction

Pathological factors may include:

Sinusitis/nasal polyps/allergy

Complications of sinusitis include:

The following points are also worth noting.

2.5 Throat

Tonsils and adenoids

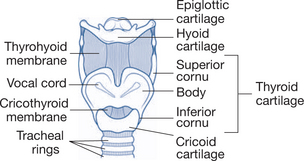

Figure 2.13 depicts the framework of the larynx and Table 2.7 lists the spaces and anatomy related to the throat.

| Parapharyngeal space | Inferior: hyoid |

| Anterior: pterygomandibular raphe | |

| Posterior: prevertebral fascia | |

| Medial: superior constrictor | |

| Lateral: parotid, mandible and lateral pterygoid | |

| Styloid process divides into: pre-styloid and post-styloid compartments | |

| Pre-styloid: fat, LN, IMA, inferior alveolar, lingual and auriculotemporal nerves | |

| Post-styloid: ICA, IJV, sympathetic chain, IX, X,XI,XII | |

| Superior: BOS | |

| Retropharyngeal space | Superior: BOS |

| Inferior: T4 where space is obliterated through fusion of oesophagus to prevertebral layer | |

| Anterior: pharynx and oesophagus | |

| Posterior: alar fascia | |

| Lateral: carotid sheath | |

| Above superior constrictor: Eustachian tube and pharyngobasilar fascia | |

| Between superior and middle constrictor: tongue, stylopharyngeus, styloid process, stylohyoid ligament, lingual nerve |

Microbiology/pathology

A number of organisms may be found in the tonsils, as listed in Table 2.8.

| Establishment of N flora of URT begins at birth | First 6–8/12 Actinomyces, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Nocardia fusobacterium increase after first dentition |

| Follow: Bacteroides, Leptotrichia, Propriobacteria, Candida | |

| AnO2: O2 — 10:1 due to [O2] | |

| Pathogenic bacteria found in healthy patients | Streptococcus pneumoniae 19% |

| Haemophilus influenzae 13% | |

| Group A streptococci 5% | |

| Moraxella 36% | |

| First three most common causative pathogens for recurrent tonsillitis | |

| Chronic illness: change of pathogens | Staphylococcus aureus |

| Gram-negative |

Infectious mononucleosis

Diagnosis

Medical treatment

Penicillin is the first-line choice for treating bacterial tonsillitis (Fig 2.14) and is used for 10 days as a minimum to avoid possible complications relating to systemic streptococcal infections. Beware of prescribing amoxicillin in undiagnosed infectious mononucleosis as this can cause a rash. Treating viral pharyngitis and glandular fever is supportive. Patients with glandular fever should be counselled against participating in contact sports to avoid splenic injury.

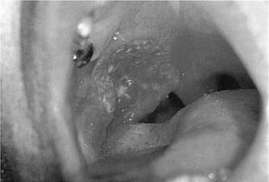

A quinsy (Fig 2.15) is a peritonsillar collection of pus, which is one of the most common complications of bacterial tonsillitis. It is managed through recognition and drainage.

2.6 Airway emergencies and tracheostomy

Assessing an airway obstruction comprises:

Performing a tracheostomy

The technique used to perform a tracheostomy is as follows.

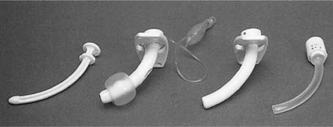

Tube types

Nonfenestrated versus fenestrated: a fenestrated tube permits the tracheostomy tube opening to be occluded during expiration that will allow air to pass the vocal cord and mouth to generate speech.

Complications

Complications from performing a tracheostomy can include:

2.7 Snoring and obstructive apnoea

There are several sites for upper airway obstruction:

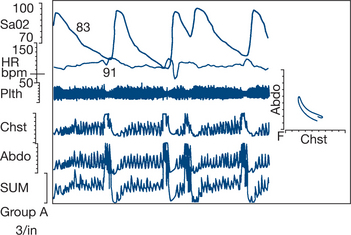

The diagnosis of severe OSA should be ruled out prior to any elective surgery on the upper airway. This is achieved with a thorough history and physical examination. A sleep study is also arranged (Fig 2.17). This involves an overnight stay in hospital with the patient being monitored.

Problems associated with OSA are:

2.8 Voice/dysphonia/hoarse voice

The larynx has three main functions:

The larynx consists of the laryngeal cartilages, bone, ligaments, membranes and muscles (Fig 2.18, Box 2.1).

Box 2.1

The anatomy of the larynx

Extrinsic: depressor — sternohyoid, thyrohyoid, omohyoid; elevators — geniohyoid, digastrics, mylohyoid, stylohyoid

Extrinsic: depressor — sternohyoid, thyrohyoid, omohyoid; elevators — geniohyoid, digastrics, mylohyoid, stylohyoidTrue vocal fold has five layers:

The true vocal fold functionally has three layers:

Dysphonia

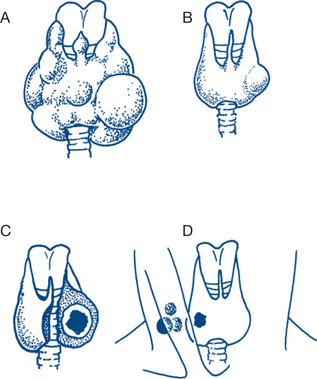

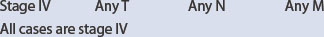

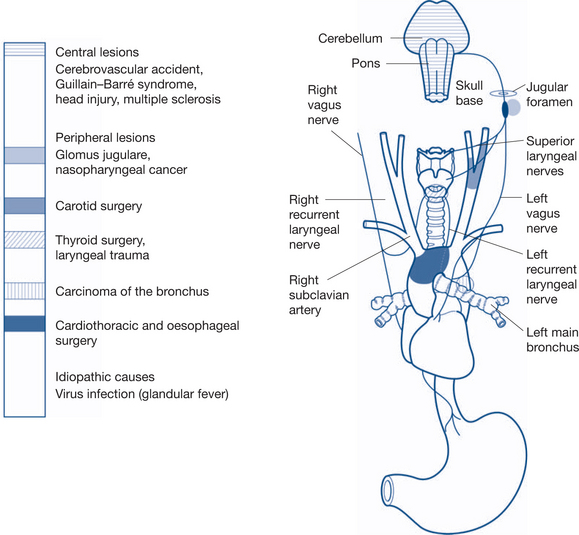

The course of the vagus nerve in the neck (Fig 2.19) is from the jugular foramen travelling down in the carotid sheath between the internal carotid artery and internal jugular vein. On the right side, it gives off the recurrent laryngeal nerve, which passes around the right subclavian artery, while on the left side it curls around the arch of the aorta.

Figure 2.19 Course of vagus nerve and potential causes of vagus palsy/hoarseness

From Dhillon & East, 2006

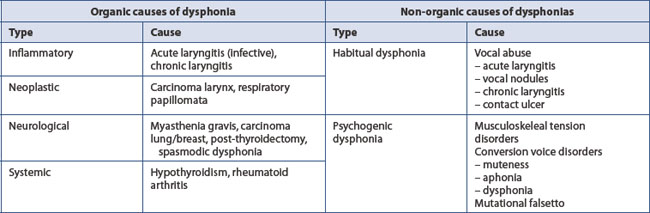

Dysphonia is the term used to describe an abnormality of a person’s normal voice; its cause can be both organic and non-organic (Table 2.9). Aphonia is the complete absence of voice production.

deep layer — conditions affecting the vocalis muscle.

Videostroboscopy also has a role in diagnosing vocal fold disorders.

2.9 Dysphagia

There are three phases to swallowing:

Dysphagia is an abnormality of swallowing (Ch 7.12). Odynophagia is pain on swallowing. When assessing dysphagia, the three stages of swallowing need to be addressed. A dynamic contrast study (barium swallow) is often performed.

2.10 Congenital anomalies

The types of branchial cysts are listed in Box 2.2.

Box 2.2

Branchial cysts

First branchial cysts, sinuses and fistulae — these are associated with the ear and may be intimately related to the facial nerve

First branchial cysts, sinuses and fistulae — these are associated with the ear and may be intimately related to the facial nerve2.11 Foreign bodies

The paradigm of history, examination, investigation and treatment should be followed.

Ear

History

A variety of foreign bodies can be found in the ear such as insects, beads and cotton bud tips.

Examination

Examination of the ear for foreign bodies is by direct inspection and tuning fork tests.

Nose

Oropharyngeal/oesophageal

2.12 Head and neck cancer

The tumour classification system often employed is the TNM classification: Tumour size, Nodal status, Metastases (Table 2.10). Depending on the TNM classification of a tumour, it is then classified as stage I, II, III or IV. Early tumours are classified stage I and II. Advanced tumours are classified stage III or IV. Generally, stages I and II have no nodal involvement — N0, stage III has early nodal involvement (N1) without distant metastases (M0) and stage IV has advanced nodal status (N2 or N3) and/or distant metastases (M1).

| TX | Primary tumour cannot be assessed. In these instances, patients present with lymphadenopathy of the head and neck with no obvious primary site tumour |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumour |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| N0 | N0 — no regional lymph node metastases |

| MX | Distant metastasis cannot be assessed |

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

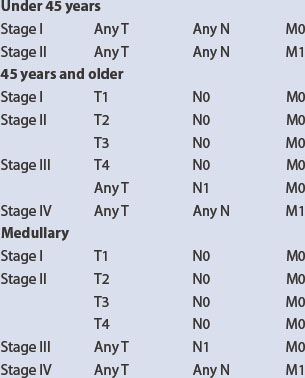

Tables 2.11 to 2.14 indicate staging for a variety of head and neck cancers. Figure 2.20 depicts a carcinoma of the tonsil.

Table 2.11 Staging for lip and oral carcinoma

| T1 T2 T3 T4 |

≤ 2 cm >2–4 cm >4 cm Invades adjacent structures |

| N1 N2 N2a N2b N2c N3 |

Ipsilateral single node ≤ 3 cm Nodes 3–6 cm Ipsilateral single >3–6 cm Ipsilateral multiple nodes ≤ 6 cm Bilateral, contralateral nodes ≤ 6 cm Nodes >6 cm |

Table 2.12 Staging for oropharyngeal carcinoma

| T1 T2 T3 T4 |

≤ 2 cm >2–4 cm >4 cm Invades adjacent structures |

| N1 N2 N2a N2b N2c N3 |

Ipsilateral single node ≤ 3 cm Nodes 3–6 cm Ipsilateral single >3–6 cm Ipsilateral multiple nodes ≤ 6 cm Bilateral,contralateral nodes ≤ 6 cm Nodes >6 cm |

Table 2.13 Staging for hypopharyngeal carcinoma

| T1 T2 T3 T4 |

≤ 2 cm and limited to one subsite >2–4 cm or more than one subsite >4 cm or with laryngeal fixation Invades adjacent structures |

| N1 N2 N2a N2b N2c N3 |

Ipsilateral single node ≤ 3 cm Nodes 3–6 cm Ipsilateral single >3–6 cm Ipsilateral multiple nodes ≤ 6 cm Bilateral, contralateral nodes ≤ 6 cm Nodes >6 cm |

Table 2.14 Staging for nasopharyngeal carcinoma

| T1 T2 T2a T2b T3 T4 |

Limited to nasophayrnx Soft tissue of oropharynx and/or nasal fossa Without parapharyngeal extension With parapharyngeal extension Invades bony structures and/or paranasal sinuses Intracranial extension, involvement of cranial nerves, infratemporal fossa, hypopharynx orbit |

| N1 N2 N3a N3b |

Unilateral metastasis in node/s ≤ 6 cm, above supraclavicular fossa Bilateral metastasis in lymph node/s ≤ 6 cm above supraclavicular fossa >6 cm In supraclavicular fossa |

2.13 Larynx

Tables 2.15 to 2.18 outline the staging for these cancers, as well as cancer affecting the salivary gland.

| T1 | One subsite, normal mobility of vocal cord |

| T2 | Involving mucosa of more than 1 adjacent subsite of supraglottis or glottis or adjacent region outside the supraglottis without fixation |

| T3 | Limited to larynx with vocal cord fixation or invades postcricoid area, pre-epiglottic tissues, base of tongue |

| T4 | Extends beyond larynx |

Table 2.16 Staging for glottic carcinoma

| T1 | Limited to vocal cord/s, normal mobility |

| T1a | Unilateral vocal cord involvement, normal mobility |

| T1b | Bilateral vocal cord involvement, normal mobility |

| T2 | Extending to supraglottis, subglottis, impaired vocal cord mobility |

| T3 | Vocal cord fixation |

| T4 | Extends beyond larynx |

Table 2.17 Staging for subglottic carcinoma

| T1 T2 T3 T4 |

Limited to the subglottis Extends to the vocal cords with normal/reduced cord mobility Cord fixation Extends beyond larynx |

| N1 N2 N2a N2b N2c N3 |

Ipsilateral single node ≤ 3 cm Nodes 3–6 cm Ipsilateral single >3–6 cm Ipsilateral multiple nodes ≤ 6 cm Bilateral, contralateral nodes ≤ 6 cm Nodes >6 cm |

Table 2.18 Staging for salivary gland carcinoma

| T1 T2 T3 T4 |

≤ 2 cm, without extraparenchymal extension >2–4 cm, without extraparenchymal extension Extraparenchymal extension and/or >4–6 cm Invades base of skull, seventh nerve and/or >6 cm |

| N1 N2 N2a N2b N2c N3 |

Ipsilateral single node ≤ 3 cm Nodes 3–6 cm Ipsilateral single >3–6 cm Ipsilateral multiple nodes ≤ 6 cm Bilateral, contralateral nodes ≤ 6 cm Nodes >6 cm |

2.14 Parotid and salivary glands

The parotid gland drains via Stensen’s duct opposite the second upper molars. The submandibular and sublingual glands drain via Warton’s duct, which opens either side of the tongue frenulum. The facial nerve is an inherent part of the parotid gland and needs to be identified during any parotid surgery. The submandibular gland has the marginal mandibular, lingual and hypoglossal nerves in close proximity, and these need to be avoided during surgery.

All salivary glands can be affected by the same pathologic processes.

Investigations

Systemic conditions that may affect the salivary glands are:

2.15 Thyroid/parathyroid

Goitre

Common causes

History

Table 2.19 sets out the process of examining a goitre.

| Examination | At what | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Look, look, look!/inspect/listen | General body habitus Hyperthyroid — proptosis, weight loss, eye signs, lid lag Hypothyroid — overweight Goitre, ask to swallow with water Redness, scarring Other neck swelling Stick out tongue Voice — ask name, stridor Finger nail changes |

Indicates hyper/hypothyroid Size of thyroid Thyroiditis, previous surgery Cervical node metastases Thyroglossal cyst Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy airway compromise |

| Feel | Goitre size, nodularity, consistency, tenderness, warmth Tethering Pulse Warmth of periphery |

Thyroid lesion Carcinoma may tether gland Hyperdynamic circulation Hyper versus hypothyroid |

| Percuss | Sternum | Retrosternal extension |

| Auscultate | Bruit | Hyperdynamic circulation |

| Dynamic manoeuvres | Pemberton’s sign Reflexes Kocher’s test |

SVC compression Brisk hyperthyroid Sluggish hypothyroid Evokes stridor |

Examination of the neck should always begin with a frontal inspection of the patient’s exposed entire head, neck and upper chest in repose, then while swallowing water from a glass. Any scars of previous operations and visible swellings are noted. The patient should sit comfortably and swallow first with the neck in a neutral position and then slightly extended to throw the gland into more prominence. The effects of lateral neck flexion and of raising both arms above the head are noted. Obstruction of the superior vena cava (SVC) may be precipitated by arm-raising, causing facial flushing and venous congestion (Pemberton’s sign). Vascular pulsation may be apparent; visible jugular veins and the level and symmetry of the jugular venous pulse and pressure waves are noted. The lower limits of lateral lobe swelling are often visible on swallowing. The position of the anatomical landmarks of the thyroid cartilage, hyoid bone and trachea are noted.

If a lower lobe’s boundary is neither visible nor palpable by these manoeuvres, it is probably retrosternal and should be further assessed by percussion over the sternum. Tracheal compression may be exposed by compressing the lateral lobes of the thyroid between both hands (Kocher’s test) to see if stridor is evoked. Fixation or attachment of the goitre to the sternomastoid muscles, the trachea and carotid vessels is assessed. Benign swellings, even when very large, displace but do not obscure the vessels; cancers can wrap around them (Berry’s sign). Examine the neck for enlarged nodes, particularly looking for prelaryngeal (Delphic) or pretracheal nodes, as well as those of the deep cervical chain and posterior triangle. Finally, listen for bruits: evidence of hyperthyroidism within the gland is established solely on this basis. If surgery is to be undertaken or if carcinoma is suspected, examination of the goitre is not complete until the cords have been assessed by indirect laryngoscopy. Paralysis of the recurrent laryngeal nerve causes an immobile cord and is usually indicative of carcinoma and occasionally of thyroiditis or previous surgery.

Common causes — specific clinical features

Single nodule

A single-nodule goitre is depicted in Figure 2.21.

Benign lesion

A short history suggests a haemorrhagic cyst or thyroiditis; an abrupt onset of a tender nodule is typical of haemorrhage into a cyst. Tenderness on palpation is the main feature of thyroiditis. Benign adenomas are usually nontender. Careful palpation is essential to exclude multinodular goitre, but it is often difficult to be sure that a nodule is truly single.

Carcinoma

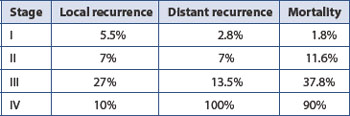

Papillary carcinoma is the most common thyroid cancer and usually presents in young adult women. Initial spread is typically lymphatic and the disease may present as a lateral or medial lymph node swelling in the neck (the primary lesion being impalpable). The tumour is well differentiated histologically and can be difficult to distinguish from normal thyroid tissue. Thyroid tissue obtained from cervical nodes was considered for some time to be aberrant thyroid tissue, but it is now realised that these findings imply a small and often impalpable, primary cancer in the thyroid. The classification and staging of thyroid carcinoma is listed in Box 2.3.

Box 2.3

Thyroid carcinoma classification and staging

N1 Regional lymph node metastases

Follicular carcinoma accounts for about 20% of malignant thyroid tumours. Follicular carcinoma can be very difficult to distinguish from a benign follicular adenoma (Box 2.4). Capsular invasion, if present, is indicative of malignancy. Follicular tumours occur more often than papillary tumours in older patients and have a greater tendency for blood-borne spread. The prognosis is therefore not as good as for papillary carcinoma.

Undifferentiated or anaplastic thyroid carcinoma is uncommon and of poor prognosis (Box 2.5).

The US-based Mayo Clinic classifies carcinoma according to the acronym MAICS (Table 2.21):

Age <39 = 3.1, >40 = 0.08 × age

Completeness of resection yes = 1, no = 0

Size 0.3 × size in centimetres.

The Lahey Clinic, also in the US, bases its classification system on the acronym AMES (Table 2.22):

| Low risk | High risk | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | <41 male, <51 female | >41 male, >51 female |

| Metastases | No | Yes |

| Extent | Intrapapillary thyroid, follicular with minor capsular invasion | Extracapsular |

| Size | <5 cm | >5 cm |

Diagnosis

Laboratory investigations of thyroid disease fall into two main categories:

Aspiration cytology

FNA is the most accurate method for predicting the likelihood of cancer in thyroid nodules and is now often the diagnostic procedure of first choice, replacing radionuclide and ultrasound studies. Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) will usually be diagnostic with anaplastic and papillary carcinomas. Distinguishing follicular adenomas from carcinomas is more difficult and less certain. Aspiration of cysts is usually both diagnostic and curative. FNAC is also very useful in diagnosing other malignancies, such as lymphomas, and in diagnosing thyroiditis, whether presenting as a nodular or diffuse enlargement.

Treatment plan

General enlargement

Single thyroid nodules

2.16 Mouth ulcers and lesions

Clinical features and treatment

Benign disease

1 ‘Dental’ ulcer

The ancient Greeks called ulcers of the mouth aphthi and recognised that they could be benign or malignant. Benign aphthous ulcers are common in children and adults, are usually found on the oral mucous membrane of the alveolar ridges or the floor of the mouth and are characteristically painful superficial ulcers with no hint of induration, with a white surface and a red, inflamed edge. Their natural history is of gradual but complete healing, but they can last for weeks or even months (major aphthae) and, if so resistant, should be regarded with suspicion. Behçet’s syndrome, consisting of recurrent aphthous ulceration and ulceration of the external genitalia and uveitis, must also be considered in intractable cases. Any hint of induration is an indication for biopsy. Treatment otherwise is symptomatic. Covering the ulcer with a surface film helps reduce pain and may facilitate healing. They are commonly associated with systemic illnesses but their cause is unknown; vitamin B12 or folic acid deficiencies may sometimes be of significance. When a mouth ulcer appears to be aphthous but is painless, chancre must be excluded in the high-risk patient.

9 Neutropenia

Oral ulceration and ulcers of other mucous membranes is a common presentation of severe neutropenia associated with lymphoma or drug toxicity. It can be a debilitating complication of cytotoxic therapy. These ulcers are very painful, indolent and chronic; they are usually sited on the palate or oropharynx and can be very difficult to heal.

2.18 Neck pain

Clinical features, diagnostic and treatment plans

1 Cervical spondylosis

X-rays of the neck may show no bony abnormality but narrowing of disc space; osteophyte formation and narrowing of the nerve root canal are commonly demonstrated on X-ray and CT examination. MRI is the most accurate investigation. Movement of the head often reproduces the symptoms. Treatment is using a soft cervical collar, analgesia and physiotherapy. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents may be very helpful. Short courses of oral steroids if medically appropriate, and radiologically guided infections of steroids, may be helpful in selected cases. Occasionally, operative decompression of a nerve root or anterior discectomy and interbody fusion are necessary for recalcitrant symptoms and signs due to nerve root or spinal cord compression.

2.19 Cranial nerve evaluation

Second (optic) cranial nerve

Retinoscopy (ophthalmoscopy) visualises the disc, retina and vessels and any abnormalities.

Third, fourth and sixth cranial nerves

Sixth nerve (abducent). Sixth nerve palsies are common. They can follow generalised increase in intracranial pressure and do not necessarily indicate a focal lesion. An internal squint is apparent and the eye does not follow an object laterally because of paralysis of external rectus.

Fifth cranial nerve (trigeminal)

The fifth nerve may be involved in herpes zoster and in trigeminal neuralgia.

Seventh (facial) cranial nerve

The much commoner unilateral lesion may be:

A facial nerve palsy causes loss of the conjunctival and corneal reflexes on the affected side only.

Ninth and tenth cranial nerves (glossopharyngeal and vagus)

These arise from motor and sensory nuclei in the medulla in the floor of the fourth ventricle and supply the muscles of the palate, pharynx and larynx, secretomotor fibres to the parotid gland and sensation (including taste) to the posterior third of the tongue, the palate and nasopharynx, oropharynx and laryngopharynx. The vagus has additionally extensive autonomic efferent connections to the heart, lungs and intestine, which are not easily subject to testing. The motor supply to the muscles of the pharynx and palate incorporates branches from the cranial root of the eleventh nerve, which run with the vagus. These muscles have bilateral cortical representation and are therefore unaffected by unilateral cerebral lesions. Upper motor neurone lesions must be bilateral to cause palatal or pharyngeal paralysis.