chapter 27 Ear, nose and throat

THE EAR

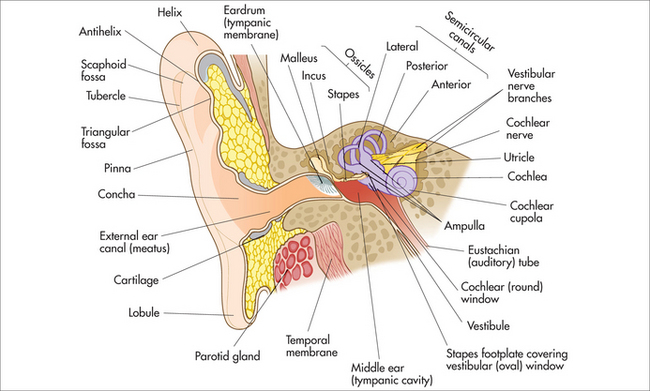

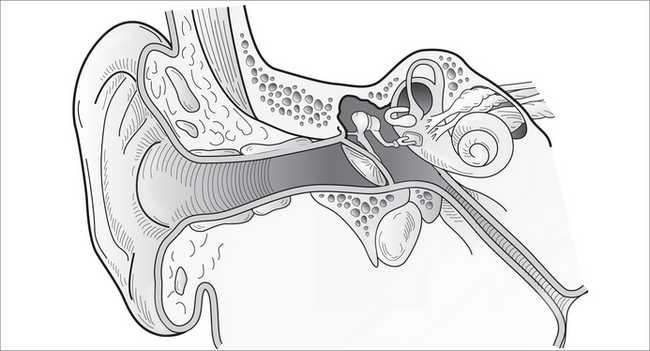

The ear is the organ of hearing. In medicine it is divided for descriptive and functional purposes into an outer, middle and inner ear (Fig 27.1). The ear amplifies sound, converting it from mechanical energy into an electrical impulse, which the individual translates. It is unusual for any disease process to affect more than one component at any one time.

OUTER EAR

The outer ear acts as a funnel, collecting sound waves and concentrating them onto the tympanic membrane (eardrum). It includes the pinna (auricle) and external auditory canal (EAC), and it represents the part accessible to examination, and is not uncommonly an area of decoration by piercing. The EAC is cylindrical in shape, and approximately 2.5 cm long. The lateral EAC is composed of cartilage, and the medial part is bony. The cartilaginous aspect contains hair, and cerumen (earwax) is produced here. The canal is lined with very specialised squamous epithelium, which self-cleans in a migratory pattern from inside to out. It is important at this stage to understand the harm caused by cotton buds in inhibiting this process. Cotton buds tend to compress wax and can cause occlusion, deafness and infection.

Trauma

‘Cauliflower ear’

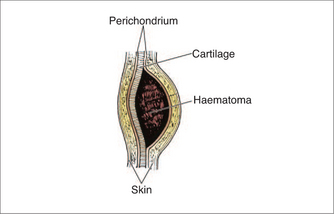

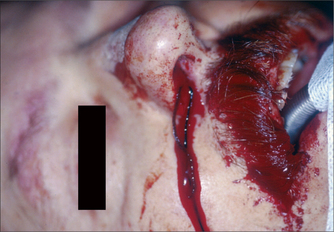

‘Cauliflower ear’ is a commonly seen injury endured by rugby players caused by blunt trauma to the ear. The shearing forces cause a sub-perichondrial haematoma, (Fig 27.2) which compromises the diffusion nutrient supply to the cartilage. The haematoma is susceptible to infection, which can further deplete nutrient supply to the cartilage. The cartilage is replaced with fibrous scar tissue and deformity results. Therefore immediate haematoma evacuation is required in cases of acute trauma.

Foreign body

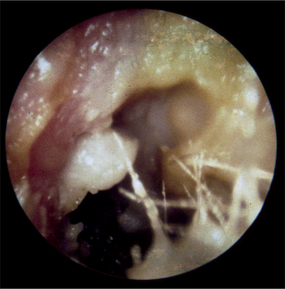

Festive seasons and birthdays often herald the season of foreign bodies in the ears of children (Fig 27.3). Anything small enough, from beads to batteries, has been found there. The deeper the foreign body, the more difficult and painful it is to remove. In children a general anaesthetic may be required. In general, appropriate equipment allows easy removal with a compliant child. The hardest to remove is often the foreign body that others have attempted to remove. It may be associated with tympanic membrane perforation, although this is unlikely and depends largely on the mechanism of trauma. If associated with a perforated eardrum, it is reassuring to know that most heal spontaneously. Water precautions should be adhered to until the eardrum heals, and an audiogram is recommended (in a perforated tympanic membrane).

Otitis externa

Ear infections are particularly common in cultures where swimming is popular. Otitis externa (OE) refers to infection of the EAC (Fig 27.4). It is commonly caused by Pseudomonas, Staphylococcus aureus or fungal species. However, because the EAC is just like skin, other causes of OE include viral infection and allergy (seborrhoeic).

A swab for culture and sensitivity of causative organisms can guide therapy decisions. The recalcitrant nature of OE is often due to inadequate use of ototopical medication. Oral antibiotics are rarely warranted for OE and reserved for systemic illness, severe surrounding cellulitis and recalcitrant infections. Topical preparations are far more effective in attaining higher antibiotic concentration at the infected site, and minimise the risk of antimicrobial resistance. It is important to perform a micro-ear toilet to clear the EAC of debris, to allow greater penetration of the antibiotics/antifungals. This is also possible with ‘tissue spears’—the corners of a tissue may be rolled and gently inserted into the ear in a twisting motion, to absorb moisture. This also allows better penetration of antibiotics and antifungals. A cotton bud has rigidity and therefore causes more trauma, whereas the tissue spear acts purely as absorbent. In severe cases of occlusion, an otowick is used. This is a cottonoid pledget that expands with ototopical antibiotic/antifungal preparations to allow delivery of the ototopical preparation to the area of inflammation/infection.

Ototopical medication has recently come under close scrutiny because of the potential toxic effect of the aminoglycosides in some ototopical medications. The Australasian Society of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgeons recently published guidelines on their use.1

Tumours

Prevention: Everyday sun protection with sunscreen, including the ears, and a hat with a broad brim.

Exostoses

Exostoses are a benign condition of the EAC seen frequently in avid swimmers, culminating over many years. They are more commonly associated with cold water exposure and are well represented in surfing communities. An osteoma is a single, solitary lump, whereas exostoses are multiple. They are smooth bony protuberances of the ear canal. Although benign in nature, they become problematic when they are large enough to inhibit the ear’s natural self-cleaning. Water trapping occurs on repeated swimming, and the ear canal becomes irritated, and macerated with attempted cleaning, and it is then only a matter of time before repeated infections occur. It is more a problem in this population as it limits the joy of the aetiology: swimming and water sports. Most are observed until they become problematic and then are surgically reduced.

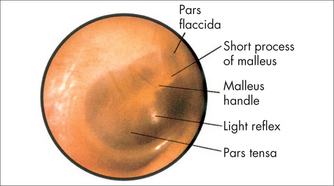

TYMPANIC MEMBRANE

The tympanic membrane (eardrum) is the Rolf Harris of the ear. It is a thin membrane separating the external auditory canal from the middle ear, approximately 10 mm in diameter (Fig 27.5). It vibrates (wobbles) in response to mechanical energy from sound waves. It is attached to the ossicles (ear bones), which together amplify sound energy to the inner ear. The tympanic membrane is important not only in sound transmission but also in preventing water entering the middle ear cleft. The respiratory epithelium of the middle ear cleft differs from the squamous epithelium of the external auditory canal. Impaired function consequently has profound effects on the hearing ability of the affected ear. Various conditions can affect the tympanic membrane, and include:

Tympanic membrane perforation

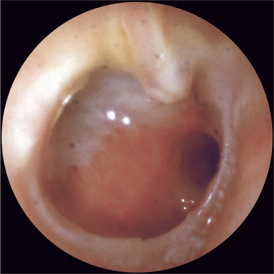

Tympanic membrane perforation (Fig 27.6) may result from trauma (personal or surgical), infection or pressure changes. It may be marginal, involving part of the tympanic membrane annulus, or central, involving any other part. It needs to be distinguished from a retraction.

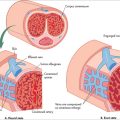

MIDDLE EAR

The middle ear is a collective term describing the space bounded by the tympanic membrane laterally and the inner ear medially. It houses the ossicles, the bones of sound conduction. It is lined by respiratory mucosa and has a connection to the posteriorly based mastoid air cells, and is drained by the eustachian tube antero-inferiorly. The external ear collects the sound waves, while the middle ear amplifies the sound transmission to the inner ear. The eustachian tube’s primary function is to allow equalisation of pressure, to maximise sound transmission.

Middle ear effusion

Failure of adequate drainage is not uncommon in children, as the eustachian tube is shorter, the diameter is thinner and it lies in a more horizontal plane than the adult eustachian tube (Table 27.1). The narrow lumen is easily obstructed in upper respiratory tract infections, there is less capacity for natural drainage, and its length is thought to allow more exposure to reflux and, hence, inflammation. Adenoidal hypertrophy may predispose to lower eustachian tube obstruction. (In the adult population, one must be wary of neoplastic postnasal obstruction.)

TABLE 27.1 Issue in a child’s eustachian tube, compared with an adult

| Anatomy | Consequence |

|---|---|

| More horizontal lie | Less capacity to drain |

| Smaller diameter | More easily occluded |

| Shorter |

Acute otitis media

Accumulation and contamination of middle ear fluid, which is normally sterile, leads to infection, otitis media. It is a common disease of the paediatric population. The patient typically presents as a febrile, runny-nose mouth breather. Again, this is because of the special relationship of the eustachian tube with the post-nasal space. Because of this relationship it may also be associated with rhinitis, sinusitis, snoring, obstructive sleep apnoea and asthma-like associations. It has an increased incidence in lower socioeconomic groups, and an alarmingly high prevalence in the Australian Indigenous population.

The controversy surrounding the use of oral antibiotics in acute otitis media has been noted. In a meta-analysis it was found that the NNT (number needed to treat to benefit one patient) was 17. The benefit was small—a reduction in pain by 12 hours. In this study, the likelihood of complications was not increased in the non-treated group.2,3 Against this, the cost of increasing antibiotic resistance, and the disruption to the ecosystem of the gut flora, have to be counted.

Complicated otitis media (see below) requires full medical treatment.

Cholesteatoma

Complications of untreated cholesteatoma include those listed in Table 27.2. Complete surgical removal is urgent, essential and unavoidable.

| Pathology | Symptom/sign |

|---|---|

| Erosion of ossicles | Deafness |

| Erosion of facial nerve | Facial palsy |

| Sigmoid sinus thrombosis/hydrocephalus | Meningism |

| Erosion of labyrinth | Balance difficulties |

| Infection petrous apex | Gardener’s sign |

| Tegmen bone erosion | Brain abscess/meningitis |

RHINOLOGY

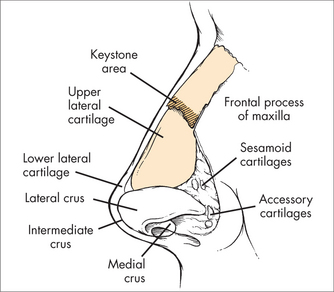

The nose is the organ of olfaction (smell), and has several important functions besides olfaction, including cleansing inspired air, humidification and warming. Functionally it has an external and an internal part (Fig 27.8). The external part contains bone and cartilage and acts to prop open the portal for air movement. The internal nose is highly vascular, particularly over the turbinates, to allow warming of air, and plays a role in nasal defence. Unfortunately, engorgement may also cause obstruction. Problems of the nose surround difficulties in the normal physiology of the nose. The two most commonly dealt with by doctors include epistaxis and sinusitis.

VESTIBULAR DISORDERS

HISTORY

EXAMINATION

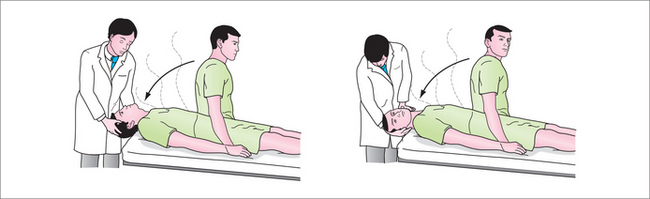

BENIGN PAROXYSMAL POSITIONAL VERTIGO

Generally there are no examination findings apart from positive Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre.

It may recur months to decades later and is treated in the same manner.

Rarely, surgical intervention is required, to occlude the posterior semicircular canal.

VESTIBULAR NEURONITIS AND LABYRINTHITIS

There is no gender predilection, and the average age of presentation is approximately 40 years.

Treatment is to encourage compensation with early mobilisation once the vertigo and nausea settle.

The patient is often referred for vestibular physiotherapy if not compensated within 4–6 weeks or if the patient has poor compensatory mechanisms (e.g. patient with walking stick, poor eyesight).

MIGRAINOUS VERTIGO

One retrospective review found that migraine treatments were effective in about 90% of patients with migraine-associated vertigo.7 Treatments included:

MÉNIÈRE’S DISEASE

During an episode, the patient classically has:

Example of a stepwise approach:

TONSILLAR AND PERITONSILLAR DISORDERS

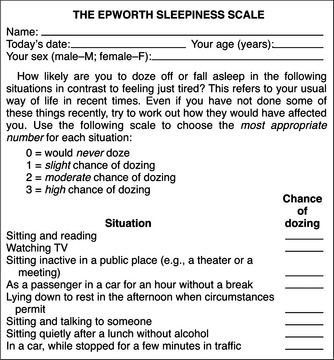

Most commonly, tonsillar and peritonsillar disorders are part of a child’s development, and surgical intervention is not often required. Infection or tonsillitis is the most common complaint of the tonsils. Symptoms and their frequency and severity often dictate treatment. It is important to assess for obstructive symptoms and, in children, for poor behaviour with morning ‘hangover’, and in adults, for daytime somnolence, poor sleep hygiene, cardiovascular comorbidity and Epworth Sleepiness Scale (Fig 27.11). Formal sleep studies may be required before making a decision on surgery.

PERITONSILAR ABSCESS (QUINSY)

Treatment is by acute drainage (incisional drainage or repeated aspiration under local anaesthetic).

LARYNGITIS

INFECTIOUS MONONUCLEOSIS

The diagnosis should be confirmed with blood tests for:

Medication

Nutrition

Supplements

Supplements help to ensure nutritional adequacy and immune support, and may include:

Herbs

A variety of herbs can be useful support for management of infectious mononucleosis. These include:

Information and patient education

Information and images of ear, nose and throat. http://www.google.com.au/images?client=safari&rls=en&q=ear+nose+and+throat&oe=UTF-8&redir_esc=&um=1&ie=UTF-8&source=univ&ei=M8fcS5T5FNCgkQX1kOjBBw&sa=X&oi=image_result_group&ct=title&resnum=11&ved=0CDUQsAQwCg.

Medline Plus, Ear, nose and throat. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/earnoseandthroat.html.

Queensland Government, Ear, nose and throat health. http://access.health.qld.gov.au/hid/EarNoseandThroatHealth/index.asp.

American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery. http://www.entnet.org/.

Australian Society of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery. http://www.asohns.org.au/.

American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery. http://www.entnet.org/.

Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. http://www.rcsed.ac.uk/site/630/default.aspx.

1 Black RJ, Cousins V, Chapman P, et al. Ototoxic ear drops with grommet and tympanic membrane perforations: a position statement. Med J Aust. 2007;187(1):62.

2 Taylor PS, Faeth I, Marks MK, et al. Cost of treating otitis media in Australia. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2009;9(2):133-141.

3 Glasziou PP, Del Mar CB, Sanders SL, et al. Antibiotics for acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;1:CD000219.

4 National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Bell’s palsy fact sheet. Last updated 2009. National Institutes of Health. Online. Available: http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/bells/detail_bells.htm#109663050.

5 Mills S, Bone K. Principles and practice of phytotherapy: modern herbal medicine. London: Churchill Livingstone, 2000.

6 Weiss RF, Fintelmann V. Herbal medicine. 2nd edn. Stuttgart: Thieme, 2000.

7 Johnson GD. Medical management of migraine-related dizziness and vertigo. Laryngoscope. 1998;108(1 pt 2):1-28.

8 Blumenthal M, Goldberg A, Brinckmann J, editors. Herbal medicine. Expanded Commission E Monographs. Austin, Texas: American Botanic Council, 2000.

9 Kim H-Y, Shin H-S, Kim Y-C, et al. In vitro inhibition of coronavirus replications by the traditionally used medicinal herbal extracts, Cimicifuga rhizoma, Meliae cortex, Coptidis rhizoma, and Phellodendron cortex. J Clin Virol. 2008;41(2):122-128.

10 Maclean W, Taylor K. The clinical manual of Chinese herbal patent medicines. Sydney: Pangolin Press, 2000.

11 Lin JC. Mechanism of action of glycyrrhizic acid in inhibition of Epstein-Barr virus replication in vitro. Antiviral Res. 2003;59(1):41-47.

12 Chang L-K, Wei T-T, Chiu Y-F, et al. Inhibition of Epstein-Barr virus lytic cycle by (–)-epigallocatechin gallate. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;301(4):1062-1068.

13 Kelly G. Rhodiola rosea: a possible plant adaptogen. Altern Med Rev. 2001;6(3):293-302.

14 Pradhan S, Girish C. Hepatoprotective herbal drug, silymarin from experimental pharmacology to clinical medicine. Indian J Med Res. 2006;124(5):491-504.

15 Barak V, Halperin I, Kalickman I. The effect of Sambucol, a black elderberry-based, natural product, on the production of human cytokines: I. Inflammatory cytokines. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2001;12(2):290-296.

16 Sanodiya BS, Thakur GS, Baghel RK, et al. Ganoderma lucidum: a potent pharmacological macrofungus. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2009;10(8):717-742.

17 Williams J. Review of antiviral and immunomodulating properties of the plants of the Peruvian rain forest with a particular emphasis on Una de Gato and Sangre de Grado. Altern Med Rev. 2001;6(6):567-579.