Chapter 83 Eales Disease

Introduction

Eales disease is an idiopathic, occlusive perivasculitis affecting peripheral retina in young men, leading to retinal nonperfusion, new vessel formation, and recurrent vitreous hemorrhages. Eales disease was reported from the UK, USA, and Canada in the latter half of the 19th century and early 20th century.1,2 The eponym originated from the first description of a syndrome of recurrent vitreous hemorrhage in young men with epistaxis and constipation by Henry Eales.3 Most cases in the last decade have been reported from the Indian subcontinent, with a few reports from Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Iran.4–13 However, the incidence of Eales disease appears to have declined globally, due probably to improved general health and living standards and reduced incidence of tuberculosis (TB),1,2,10 as well as to improved etiologic diagnosis in a heterogeneous group of allegedly primary vasculitides, previously amalgamated as presumed Eales disease.14 Most patients are healthy young men, aged 20–40 years; the mean age of onset is generally earlier in Asians than in Caucasians.2,15–17

Clinical features and natural history

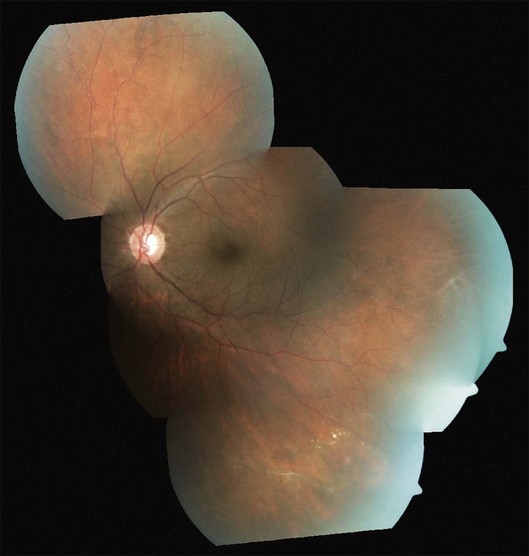

Three sequential vascular responses which determine the natural course of Eales disease are inflammation, occlusion, and neovascularization.1,2,10,15 Most patients are asymptomatic at the stages of inflammation and occlusion. The disease starts quietly as multiple, peripheral inflammatory branch retinal vein occlusions: fine, solid white lines representing venous sheathing are the commonest clinical presentation (Fig. 83.1).1,2 As active vasculitis slowly resolves, the fuzzy vascular sheathing, with indistinct margins, becomes well defined and distinct. Retinal arteries may be involved later, but their involvement is not central to the disease presentation,1 and is generally suggestive of other conditions like systemic vasculitides.11,18 Other clinical features which suggest alternative inflammatory etiologies are exudative or focal vasculitis, cotton-wool spots,11,18 and central retinal involvement including macular and optic disc edema, choroiditis, anterior uveitis, and vitritis.2,14

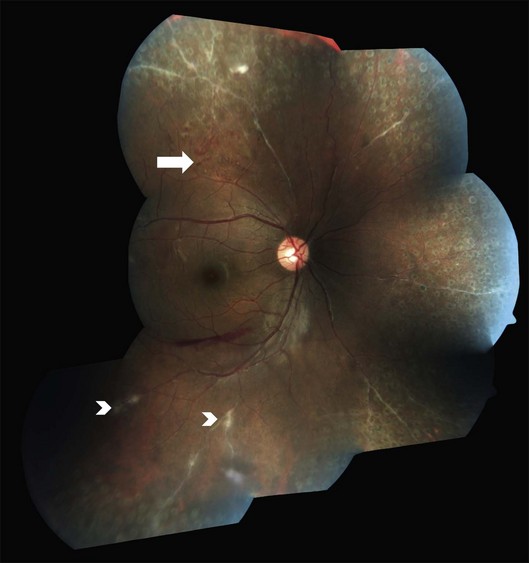

As the occlusions are primarily venous, they occur gradually, allowing development of compensatory phenomena like collaterals, microaneurysms, capillary telangiectasia, corkscrew vessels, and venous beading; some of these changes may be observed by careful examination of the apparently uninvolved fellow eye of a patient with unilateral involvement. Prolonged and extensive retinal nonperfusion eventually leads to peripheral neovascularization in up to 80% of eyes; disc neovascularization is rare.2,4,15 New vessels bleed into vitreous, resulting in the classic presentation of Eales disease: a sudden, unilateral blurring of vision or floaters15,17 (Fig. 83.2). Vision often improves, but recurrences are common. The second eye is ultimately affected in 50–90% of cases, after a gap of 3–10 years.2,4,14,15 Isolated episodes of vitreous hemorrhage usually settle down without visual deficit; recurrent bleeds lead to progressive contraction of vitreous cortex, resulting in tractional retinal detachments, secondary retinal tears, and epimacular membranes.1 Though anterior-segment neovascularization occurs in a small fraction of eyes, the prognosis is better than what is typically associated with iris neovascularization.4

Charamis graded the evolution of Eales disease into four stages. Stage I was characterized by mild peripheral perivasculitis; stage II by extensive inflammation involving larger vessels; neovascularization and vitreous hemorrhage heralded stage III; and tractional complications marked stage IV.19 A system for grading Eales disease on the basis of the degree and extent of retinal vasculopathy, neovascular proliferations, and vitreous hemorrhage has also been proposed.20 However, the course of the disease is variable, and a fixed sequence of stages may not be followed consistently.1,2

Pathology and pathogenesis

The classic histopathological connotation of the term “vasculitis” is a type III hypersensitivity reaction with deposition of immune complexes in the vessel wall.21 This definition is not applicable to retinal vasculitis in general, and Eales disease in particular, which represents perivascular cuffing with inflammatory cells, graded by clinical appearance rather than vascular caliber or type of immune response.11,21 Most authors have therefore used the terms “vasculitis” and “perivasculitis” interchangeably in the context of Eales disease.

Central to the visually debilitating complications of Eales disease is retinal hypoxia. Inflammation causes hypoxia by an increase in the metabolic demands of cells and a reduction in metabolic substrates caused by inflammatory vascular occlusion. Hypoxia in turn triggers further inflammation, setting up a vicious cycle.22 This sequence suggest a pathogenetic role for both angiogenic factors and inflammatory cytokines in Eales disease, in a manner similar to noninflammatory vascular diseases like diabetic retinopathy. A simultaneous upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and interleukins (IL-6 and IL-9) has indeed been observed during the proliferative phases of both diabetic retinopathy and Eales disease.7 Other biochemical analyses have also implicated retinal autoimmunity, angiogenic growth factors, and oxidative stress in causing inflammation and neovascularization in Eales disease.2 Recent serologic and genetic studies have reinforced the role of cell-mediated immunity in Eales disease, particularly interleukins and tumor necrosis factor-alpha.9,12

The pathogenesis of inflammatory vascular occlusions in Eales disease remains unclear. Systemic association with neurological, vestibuloauditory, hematological, and parasitic diseases and infections have been proposed but never proven.2,15 The most frequently reported association is with systemic TB. While viable organisms have not been demonstrated from the eyes with Eales disease, polymerase chain reaction-based studies have identified mycobacterial DNA in vitreous and epiretinal tissue.23,24 These findings make the case for hypersensitivity to tuberculoprotein; the case is reinforced by the presence of Mantoux tuberculin skin test positivity in the majority of patients.2 This concept continues to be popular among current researchers.11 Several other studies have however disputed this notion by demonstrating Mantoux positivity in healthy controls, as well as Mantoux negativity among Eales patients.2,15,25

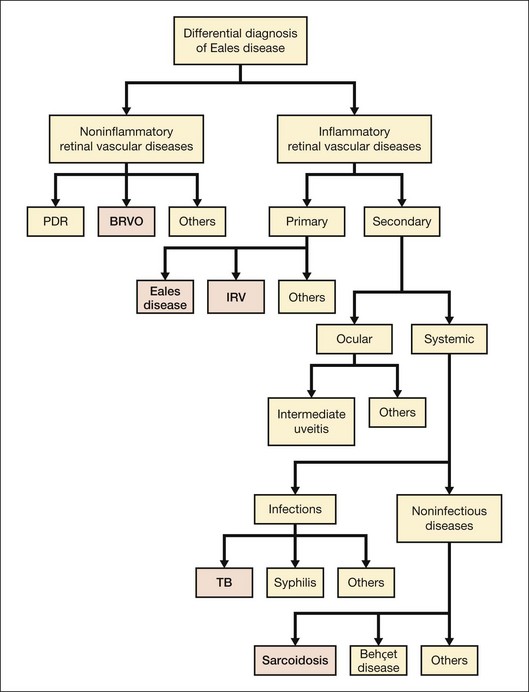

Differential diagnosis

Eales disease is a diagnosis of exclusion (see Fig. 83.3). Several ocular and systemic inflammatory and noninflammatory diseases cause retinal vascular sheathing or occlusion, which may closely resemble Eales disease. However, a battery of investigations is not necessary for every patient. A detailed history and a thorough systemic examination rule out most of the mimicking diseases; only a few tailored investigations are required to clinch the diagnosis.

Among noninflammatory vascular occlusions, primary branch retinal vein occlusion mimics Eales most closely. The former occurs at an arteriovenous crossing; the crossing artery is frequently sclerosed. The occlusions are not multiple and peripheral like Eales, and affect older age groups. Proliferative diabetic retinopathy may also exhibit sheathing of vessels during active stage (as part of the appearance labeled “featureless retina”) or at involutional stage. Central retinal vein occlusion in a young adult should be investigated for inflammatory etiology (see diagnostic workup, below) because it represents a rare presentation of Eales.1 Coats disease, familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR) and sickle-cell disease also show similar peripheral nonperfusion and should be ruled out. Though Coats disease also occurs in male patients, they are typically younger and have unilateral disease with prominent telangiectasia, more exudation, and less neovascularization or vitreous hemorrhage. FEVR and sickle-cell retinopathy have distinctive clinical and angiographic features, as well as familial and systemic associations respectively, to distinguish them from Eales disease.

Ocular inflammatory conditions like intermediate uveitis, endophthalmitis, multifocal choroiditis, and birdshot retinopathy may have associated retinal vasculitis, but primary lesions are generally prominent and unmistakable. Systemic TB should be ruled out in every case of retinal vasculitis because of its endemic presence, especially in the Indian subcontinent.26 However, TB typically causes anterior and/or posterior uveitis along with retinal vasculitis, which is generally florid and associated with vitritis and choroiditis.26 Syphilis, like TB, needs to be screened by default because of its recent re-emergence with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), as well as its protean and nonpathognomonic presentations, though uveitis is most frequent.27 Retinal periphlebitis occurs in about half the cases of leptospirosis, the most widespread zoonosis globally. Nongranulomatous uveitis, vitritis, and papillitis help in differentiation.28 Retinal vasculitis can also occur along with necrotizing retinitis, though arteries are involved more commonly.11

Like TB and syphilis, sarcoidosis also has no pathognomonic signs, and needs to be ruled out in most ocular inflammations. Vasculitis is typically segmental and nodular, with snowball vitreous exudates and granulomatous uveitis. Diagnosis is based on key ophthalmic signs and laboratory investigations.29 Although uncommon, Behçet disease is the classic presentation of occlusive retinal vasculitis along the Silk Route. It involves both arteries and veins, and is accompanied by severe uveitis, vitritis, and retinal infiltrates; orogenital aphthoses are diagnostic.30 Systemic vasculitides primarily cause retinal arterial occlusions rather than vasculitis: only small-vessel vasculitis, specifically systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), is worth a mention in the differential diagnosis of Eales disease. SLE manifests more like hypertensive retinopathy than vasculitis, presenting typically with cotton-wool spots and retinal hemorrhages, and sometimes, choroidopathy.31

Primary retinal vasculitis

Once the diseases causing secondary vasculitis are ruled out, the two main conditions which remain in the picture are Eales disease and idiopathic retinal vasculitis. When the vasculitis is more posterior, sectorial and exudative; neovascularization, vitreous hemorrhage, and recurrences are uncommon; and presentation is gender-neutral, some authorities prefer the term “idiopathic retinal vasculitis” rather than Eales disease.2 Though the differentiation is rather semantic as workup remains the same (see below), Eales disease has the unusual combination of minimal peripheral vascular inflammation but extensive vascular occlusions and neovascularization leading to recurrent vitreous hemorrhages, justifying the continued use of the eponym.2

Diagnostic workup for eales disease

The purpose of the workup is to search for a cause for vasculitis and to rule out infections. This is best done by meticulous history-taking and systemic examination; laboratory investigations should be tailored to the positive findings from history and examination.32

A detailed examination for systemic disease, especially for skin and mucosa, joints, respiratory and central nervous systems by an internist rules out important systemic associations, some of which may be life-threatening. Only a few basic screening investigations are universally required in retinal vasculitis which the ophthalmologist should order before referral to the internist: a complete hemogram, peripheral smear, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, tuberculin skin test, chest X-ray, rapid plasma reagin (RPR for syphilis), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for HIV, and urinanalysis are sufficient to screen for most common diseases causing vasculitis; further investigations are required only when history, examination, and/or aforementioned investigations point towards a specific disease.11,32

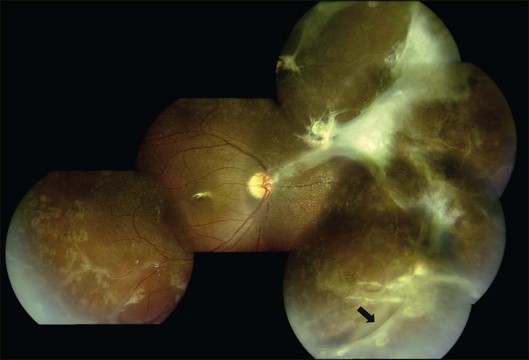

Fluorescein angiography helps mainly to identify peripheral new vessels and the extent of retinal nonperfusion, bordered by compensatory phenomena like collaterals and microaneurysms (Fig. 83.4). Active vasculitis appears as leakage from the stained vessel walls, though it can be detected clinically. B-scan ultrasound is a key presurgical investigation to assess the retinal status, posterior vitreous detachment (PVD), and tractional membranes obscured by vitreous hemorrhage. While assessing PVD, one must beware of vitreoschisis and an anomalous PVD, both common in Eales disease.33

Management

Patients with resolved vasculitis and clear media should be followed up at 6–12-month intervals. When the vision is good and the macula is healthy, minimal peripheral vasculitis may also be observed, though with close follow-up.2,32

Once systemic and ocular infections have been ruled out by history, examination, and investigations, corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment for active vasculitis. Periocular depot steroids like triamcinolone acetonide, 40 mg/mL, are effective in most cases with unilateral disease.34 When the vasculitis is bilateral or severe, or when there is inadequate response to periocular injections, systemic corticosteroids (typically, oral prednisolone, 1 mg/kg body weight/day) should be considered.34 In the authors’ experience, corticosteroids by these two routes are almost always enough to control the inflammation in Eales disease; immunosuppressive agents are rarely required. A small short-term case series reported successful resolution of active vasculitis in Eales disease with intravitreal injection of triamcinolone acetonide, 4 mg/mL.5 The rationale of choosing intravitreal over sub-Tenon’s route and the potential predicament of bilateral treatment were not explained. In the presence of a positive tuberculin test, some investigators recommend antitubercular therapy.1,15 However, its role in the treatment of Eales disease is unproven and controversial, and should be decided by an internist.2

Peripheral scatter photocoagulation in the areas with new vessels, preferably guided by angiographic retinal nonperfusion, is the treatment of choice once the proliferative stage is reached.1,2,4,10,14,15 Treatment should be extended posteriorly according to the posterior spread of the retinal nonperfusion and the presence of posterior or disc neovascularization.2 Scatter photocoagulation is not recommended for peripheral retinal nonperfusion in the absence of neovascularization: peripheral nonperfusion is nearly universal in eyes with Eales disease.20 Photocoagulation is also contraindicated in the presence of active vasculitis, which is likely to flare up and release more angiogenic factors, aggravating neovascularization (Fig. 83.5).2 Pretreatment with corticosteroids sometimes mitigates the need for subsequent photocoagulation as well.

Persistent vitreous hemorrhage is the most frequent indication for vitrectomy. Early intervention (within 3–6 months) begets better visual outcomes;35 epimacular membranes or extramacular retinal detachment warrant consideration of early vitrectomy; and macular detachment mandates immediate vitrectomy. Results of vitrectomy in Eales disease have been reported for about three decades; however, there is marked discrepancy in the reported outcomes due to variability in case selection, mainly PVD status and retinal detachment.4,8,33,35 With modern surgical instrumentation, good surgical outcomes are possible in spite of incomplete or anomalous PVD and tractional sequelae (Fig. 83.6).8 Encircling belt buckles may help improve the anatomical outcomes of vitrectomy in the presence of peripheral tractional membranes.8 Recently, anti-VEGF drugs like bevacizumab and ranibizumab have been used as adjuvants to scatter photocoagulation and vitrectomy. While bevacizumab probably has merit in treating neovascularization refractory to scatter photocoagulation6 and as an adjuvant to vitrectomy, it cannot substitute vitrectomy for vitreous hemorrhage in Eales disease, and can precipitate tractional complications.13 The patient should therefore be cautioned about the need for vitrectomy prior to anti-VEGF injection.

Summary

Though numerous ocular and systemic diseases cause retinal vasculitis, isolated retinal vasculitis, as seen in Eales disease, has few systemic associations.36 A detailed history and clinical examination, and specific investigations as indicated by the positive findings are cost-effective and sufficient. Once the diagnosis of Eales disease is established, most cases are usually observed;14 corticosteroids are required when vasculitis is significant. Peripheral scatter photocoagulation is effective in the proliferative disease, but should be delayed in favor of corticosteroids in the presence of active inflammation. Recurrent vitreous hemorrhage and tractional complications require consideration of early vitrectomy. With judicious use of medical and surgical treatment options, visual prognosis is good in most cases. While corticosteroids and scatter photocoagulation remain the standard of care, pharmacotherapy using antiangiogenic molecules, antioxidants, and antibodies against specific inflammatory cytokines may play a larger role in the future treatment of this enigmatic disease.2,7,9,12

1 Patnaik B, Nagpal PN, Namperumalsamy P, et al. Eales disease: clinical features, pathophysiology, etiopathogenesis. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 1998;11:601–618.

2 Biswas J, Sharma T, Gopal L, et al. Eales disease – an update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47:197–214.

3 Eales H. Retinal haemorrhages associated with epistaxis and constipation. Brim Med Rev. 1880;9:262.

4 Atmaca LS, Batioglu F, Atmaca Sonmez P. A long-term follow-up of Eales’ disease. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2002;10:213–221.

5 Ishaq M, Feroze AH, Shahid M, et al. Intravitreal steroids may facilitate treatment of Eales’ disease (idiopathic retinal vasculitis): an interventional case series. Eye. 2007;21:1403–1405.

6 Kumar A, Sinha S. Rapid regression of disc and retinal neovascularization in a case of Eales disease after intravitreal bevacizumab. Can J Ophthalmol. 2007;42:335–336.

7 Murugeswari P, Shukla D, Rajendran A, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines and angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors in vitreous of patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy and Eales’ disease. Retina. 2008;28:817–824.

8 Shukla D, Kanungo S, Prasad NM, et al. Surgical outcomes for vitrectomy in Eales’ disease. Eye. 2008;22:900–904.

9 Saxena S, Pant AB, Khanna VK, et al. Interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha: novel targets for immunotherapy in Eales disease. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009;17:201–206.

10 Das T, Pathengay A, Hussain N, et al. Eales’ disease: diagnosis and management. Eye. 2010;24:472–482.

11 El-Asrar AMA, Herbort CP, Tabbara KF. A clinical approach to the diagnosis of retinal vasculitis. Int Ophthalmol. 2010;30:149–173.

12 Sen A, Paine SK, Chowdhury IH, et al. Association of interferon-gamma, interleukin-10, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene polymorphisms with occurrence and severity of Eales’ disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:171–178.

13 Patwardhan SD, Azad R, Shah BM, et al. Role of intravitreal bevacizumab. In: Eales disease with dense vitreous hemorrhage: a prospective randomized control study. Retina. 2011;31:866–870.

14 Schubert HD. Eales’ disease. In: Guyer DR, Yannuzzi LA, Chang S, et al. Retina – vitreous – macula. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1999:415–420.

15 Das T, Biswas J, Kumar A, et al. Eales’ disease study. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1994;42:3–18.

16 Elliot AJ. Recurrent intraocular hemorrhage in young adults (Eales’s disease); a report of 31 cases. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1954;52:811–875.

17 Spitznas M, Meyer-Schwicherath G, Stephan B. The clinical picture of Eales’ disease. Graefes Arch Klin Exp Ophthalmol. 1975:73–85.

18 Stanford MR, Verity DH. Diagnostic and therapeutic approach to patients with retinal vasculitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2000;40:69–83.

19 Charamis J. On the classification and management of the evolutionary course of Eales’ disease. Trans Ophthalmol Soc UK. 1965;85:157–160.

20 Das TP, Namperumalsamy P. Photocoagulation in Eales’ disease. Results of prospective randomised clinical study. Presented in XXVI Int Cong Ophthalmol, Singapore. 1990.

21 Graham EM, Stanford MR, Whitcup SM. Retinal vasculitis. In: Pepose JS, Holland GN, Wilhelmus KR. Ocular infection and immunity. St. Louis: Mosby; 1996:538–551.

22 Eltzschig HK, Carmeliet P. Hypoxia and inflammation. N Engl J Med. 2011;17:656–665.

23 Biswas J, Therese L, Madhavan HN. Use of polymerase chain reaction in detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex DNA from vitreous sample of Eales’ disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:994.

24 Madhavan HN, Therese KL, Gunisha P, et al. Polymerase chain reaction for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in epiretinal membrane in Eales’ disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:822–825.

25 Muthukkaruppan V, Rengarajan K, Chakkalath HR, et al. Immunological status of patients of Eales’ disease. Indian J Med Res. 1989;90:351–359.

26 Bansal R, Gupta A, Gupta V, et al. Role of anti-tubercular therapy in uveitis with latent/manifest tuberculosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:772–779.

27 Chao JR, Khurana RN, Fawzi AA, et al. Syphilis: reemergence of an old adversary. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:2074–2079.

28 Shukla D, Rathinam SR, Cunningham ET, Jr. Leptospiral uveitis in the developing world. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2010;50:113–124.

29 Herbort CP, Rao NA, Mochizuki M. International criteria for the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis: results of the first international workshop on ocular sarcoidosis (IWOS). Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009;17:160–169.

30 Davatchi F, Shahram F, Chams-Davatchi C, et al. Behçet’s disease in Iran: analysis of 6500 cases. Int J Rheum Dis. 2010;13:367–373.

31 Aristodemou P, Stanford M. Therapy insight: the recognition and treatment of retinal manifestations of systemic vasculitis. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2006;2:443–451.

32 George RK, Walton RC, Whitcup SM, et al. Primary retinal vasculitis. Systemic associations and diagnostic evaluation. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:384–389.

33 Badrinath SS, Gopal L, Sharma T, et al. Vitreoschisis in Eales’ disease: pathogenic role and significance in surgery. Retina. 1999;19:51–54.

34 George RK, Nussenblatt RB. Treatment of retinal vasculitis. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 1998;11:673–680.

35 Kumar A, Kumar A, Tiwari HK, et al. Comparative evaluation of early vs. deferred vitrectomy in Eales’ disease. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2000;78:77–78.

36 Saurabh K, Das R, Biswas J, et al. Profile of retinal vasculitis in a tertiary eye care center in Eastern India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2011;59:297–301.