Chapter 31 Dyslexia

Pathogenesis

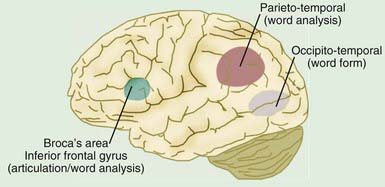

A range of neurobiologic investigations using primarily functional brain imaging suggest that there are differences in the left temporo-parieto-occipital brain regions between dyslexic and nonimpaired readers. Functional brain imaging in both children with dyslexia and adult dyslexic readers demonstrates a failure of the left hemisphere posterior brain systems to function properly during reading, with increased activation in the frontal regions, a pattern referred to as the neural signature of dyslexia. Thus, functional brain imaging has for the first time made visible what has always been a hidden disability. These data suggest that rather than the smoothly functioning and integrated reading systems observed in nonimpaired children (Fig. 31-1), inefficient functioning of the posterior reading systems results in dyslexic children’s attempting to compensate by shifting to other, ancillary systems, for example, anterior sites, such as the inferior frontal gyrus. In dyslexic readers, inefficient functioning of the posterior reading systems underlies the failure of skilled reading to develop, whereas a shift to ancillary systems supports accurate, but not automatic word reading.

Clinical Manifestations

Anxiety is often present and increases over time. Dyslexia may co-occur with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (Chapter 30); this comorbidity has been documented in both referred samples (40% comorbidity) and nonreferred samples (15% comorbidity).

Ferrer E, Shaywitz BA, Holahan JM, et al. Uncoupling of reading and IQ over time: empirical evidence for a definition of dyslexia. Psychol Sci. 2010;21(1):93-101.

Fletcher JM, Lyon GR, Fuchs LS, et al. Learning disabilities: from identification to intervention. New York: Guildford Press; 2007.

Lonigan C. Development and promotion of emergent literacy skills in children at risk of reading difficulties. Baltimore: York; 2003.

Lyon GR, Shaywitz SE, Shaywitz BA. A definition of dyslexia. Ann Dyslexia. 2003;53:1-14.

Marzola E, Shepherd M. Assessment of reading difficulties. In: Birsh JR, editor. Multisensory teaching of basic language skills. Baltimore: Brookes; 2005:171-185.

National Reading Panel. Teaching children to read: an evidence based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction (NIH pub. no. 00-4754). Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2000.

Pennington B. Diagnosing learning disorders, second edition: a neuropsychological framework. New York: Guilford Press; 2008.

Shaywitz B, Skudlarski P, Holahan J, et al. Age-related changes in reading systems of dyslexic children. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:363-370.

Shaywitz S. Overcoming dyslexia: a new and complete science-based program for reading problems at any level. New York: Alfred A. Knopf; 2003.

Shaywitz SE, Morris R, Shaywitz BA. The education of dyslexic children from childhood to young adulthood. Ann Rev Psychol. 2008;59:451-475.

Shaywitz SE, Shaywitz BA. Dyslexia (specific reading disability). Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1301-1309.

Shaywitz SE, Shaywitz BA. Paying attention to reading: the neurobiology of reading and dyslexia. Dev Psychopathol. 2008;20:1329-1349.

Stahl S, Heuback K. Fluency-oriented reading instruction. J Lit Res. 2005;37:25-60.