CHAPTER 4

Duodenum and Small Bowel

INTRODUCTION

Routine endoscopy is primarily limited to examination of the duodenal bulb and second portion of the duodenum, with an occasional glimpse of the third portion. With the availability of small-bowel enteroscopes and more recently of capsule technology, the entire small bowel can be visualized. The duodenal bulb appears as a small, round cavity with a finely granular appearance. At the superior duodenal angle, which marks the junction of the first and second portions, Kerckring’s valves, or the circular folds, become visible. In contrast with the bulb, the mucosa assumes a more granular and frequently whitish appearance. The ampulla occasionally may be identified on the medial wall, especially when prominent. The intimacy of the pancreas and biliary system to the duodenum may be reflected by endoscopic lesions resulting from diseases of pancreaticobiliary tree.

Duodenal disease is generally limited to the bulb, where inflammatory disorders, erosions, and ulcers are found. Neoplasms typically reside in the distal duodenum, jejunum, or ileum, and thus remain endoscopically hidden with routine endoscopy. If required, examination of the distal duodenum can be accomplished with a pediatric colonoscope or dedicated enteroscope. The anterior–posterior relationships in the duodenal bulb are important to understand, particularly when characterizing ulcer disease in the setting of gastrointestinal hemorrhage. The terminal ileum can be evaluated at the time of colonoscopy in most cases. In some situations, intubation of the terminal ileum should be routine; for example, when evaluating for Crohn’s disease or when finding fresh blood in the cecum in a patient with gastrointestinal bleeding. The identification of small-bowel lesions by capsule endoscopy may now be amenable to endoscopic therapy with the double-balloon endoscope.

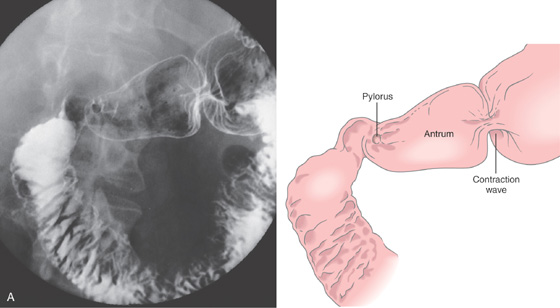

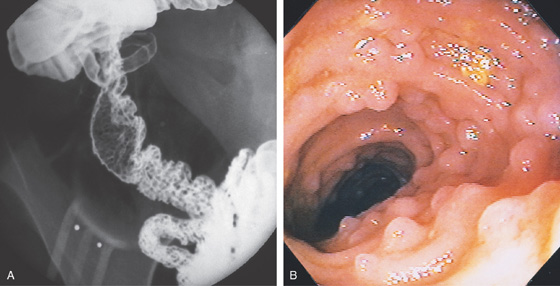

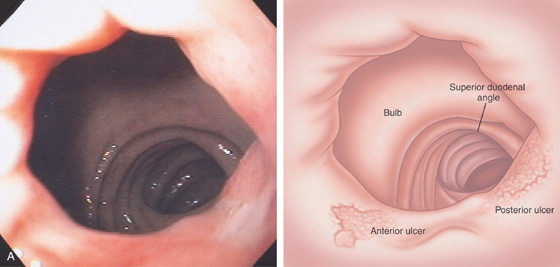

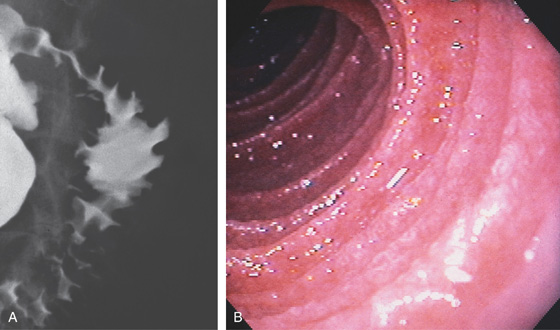

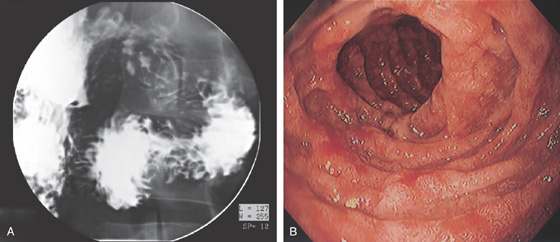

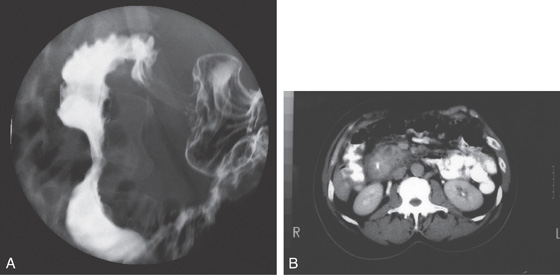

Figure 4.1 NORMAL DUODENUM

A, Upper gastrointestinal barium series demonstrates a normal-appearing duodenal bulb, with barium in the second duodenum (C sweep) and distal duodenum. The pylorus is seen en face.

B, The distal duodenum and proximal jejunum have a characteristic feathery appearance. The distal duodenum and proximal jejunum are seen coursing behind the antrum.

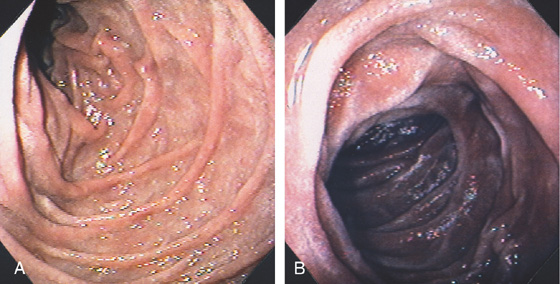

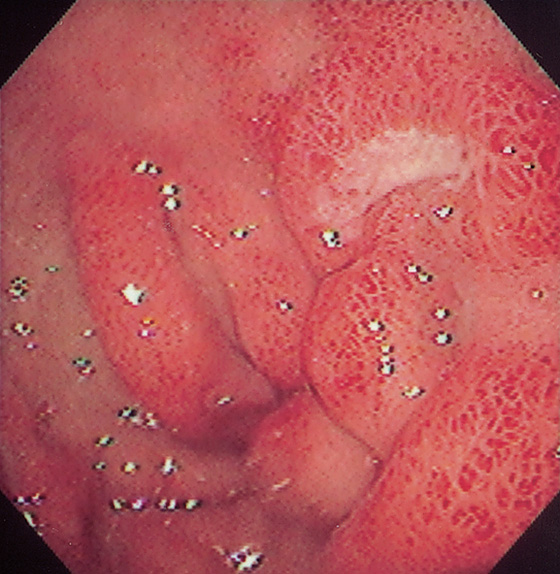

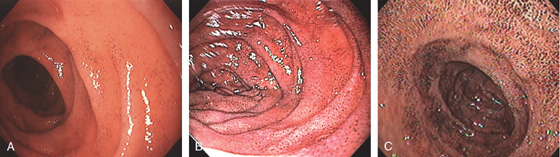

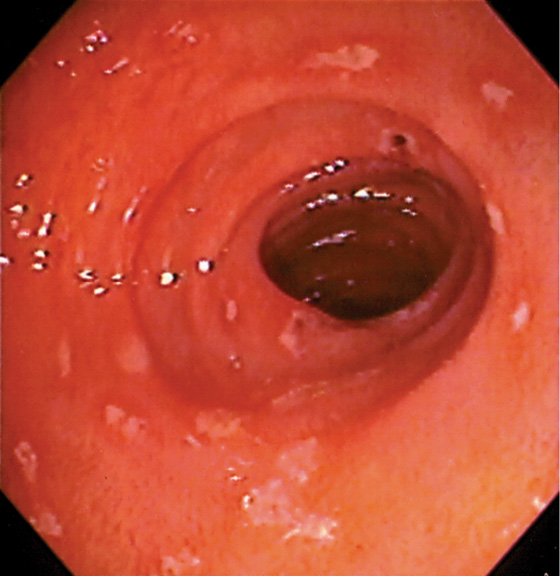

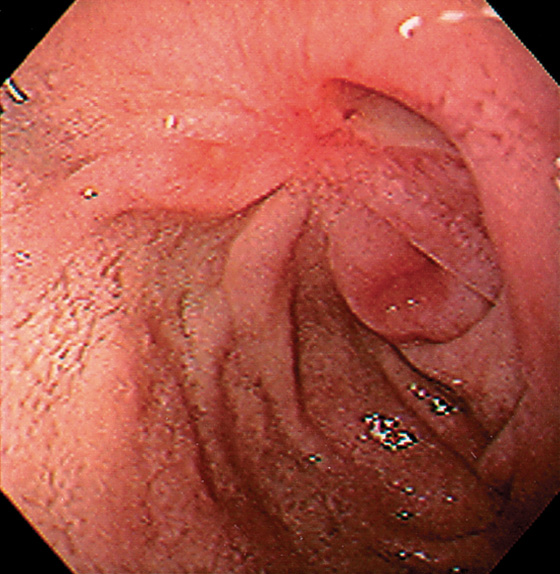

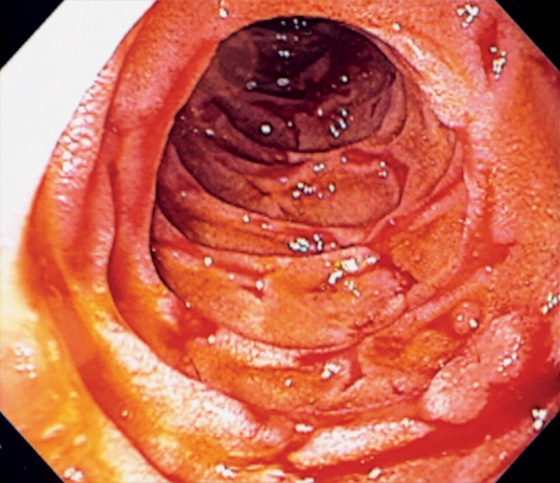

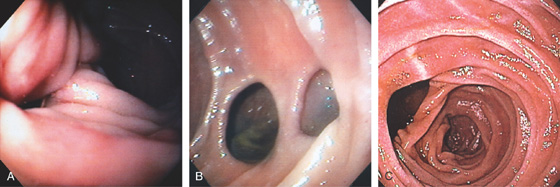

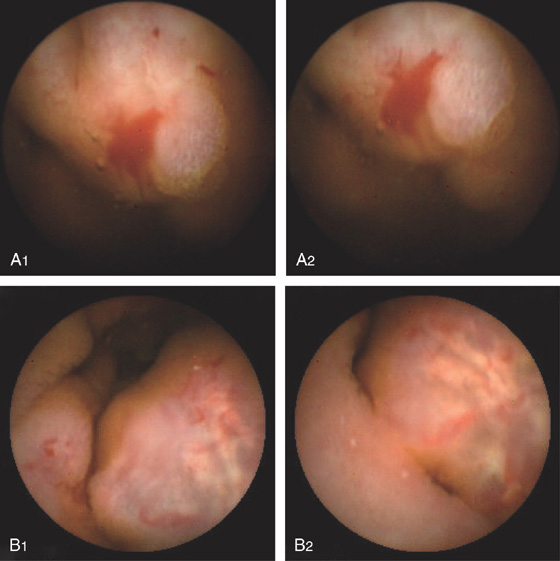

Figure 4.2 NORMAL DUODENAL BULB

A, The mucosa is not smooth but has a subtle textured appearance. The superior duodenal angle marks the junction between the distal duodenal bulb and the second duodenum. Vascularity can usually be appreciated. B, The vascular pattern is more pronounced. No real angle exists between the bulb and the second portion of the duodenum in this patient. The circular folds of the second duodenum are shown.

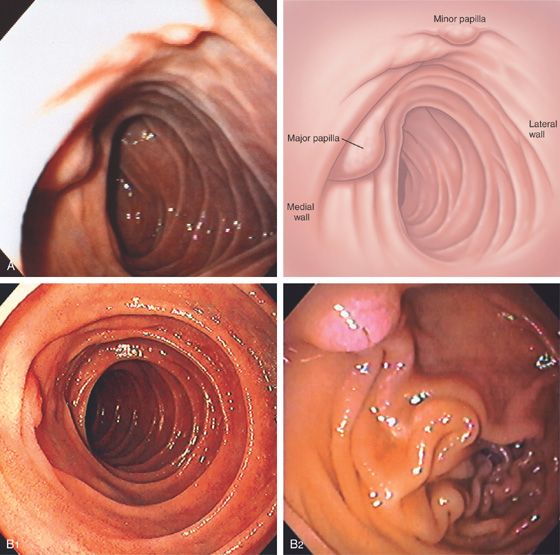

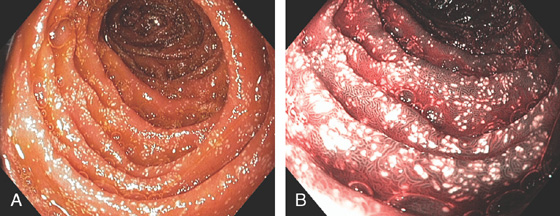

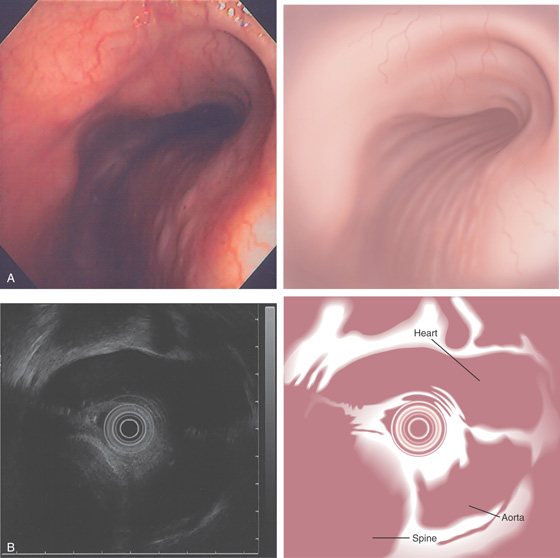

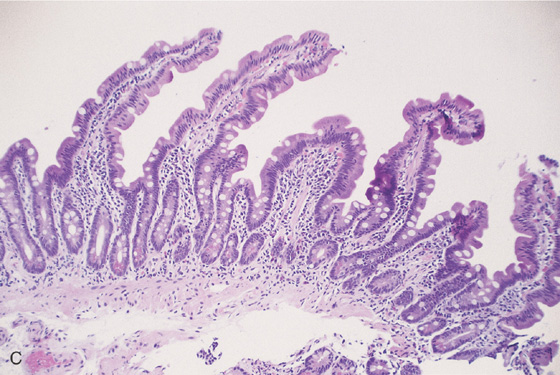

Figure 4.3 SECOND DUODENUM

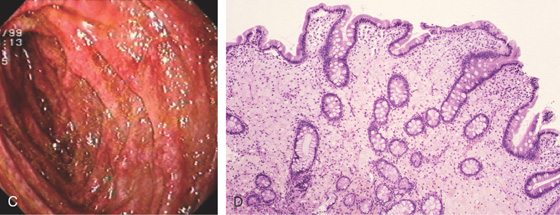

A, The second duodenum is characterized by circular folds termed valvulae conniventes or Kerckring’s valves. The mucosa has a granular appearance. The junction of the second and third duodenum (inferior duodenal angle) is in the distance. B, The mucosa may have a frosty white appearance.

C, The duodenal mucosa is characterized by slender villi composed of goblet cells.

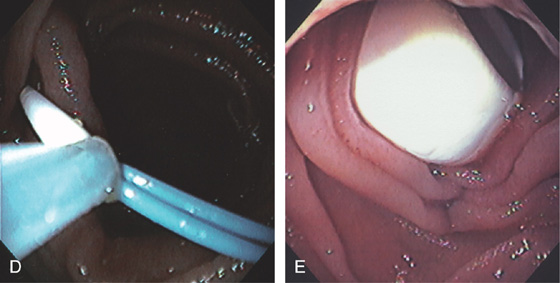

Appearance as shown by magnification endoscopy (D) and narrow band (E) imaging.

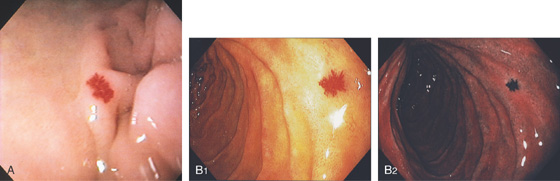

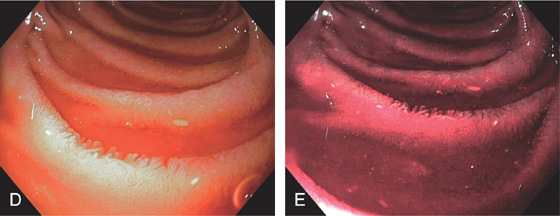

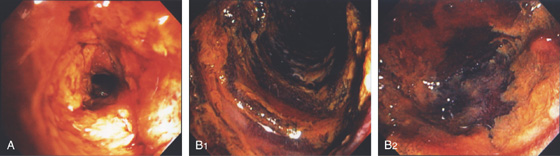

Figure 4.4 MAJOR AND MINOR PAPILLAE

A, The major papilla is seen on the medial wall of the mid-second duodenum; the minor papilla is shown proximally and in a superior position. B1, Small, polypoid-like lesion on the medial wall in the mid-second duodenum. B2, The papilla can be seen in a more en face view. The ampullary orifice is visible, and just distal is the longitudinal fold. B3, The major papilla is small and well seen with the forward viewing endoscope. (Drawing) Folds lead to the papilla.

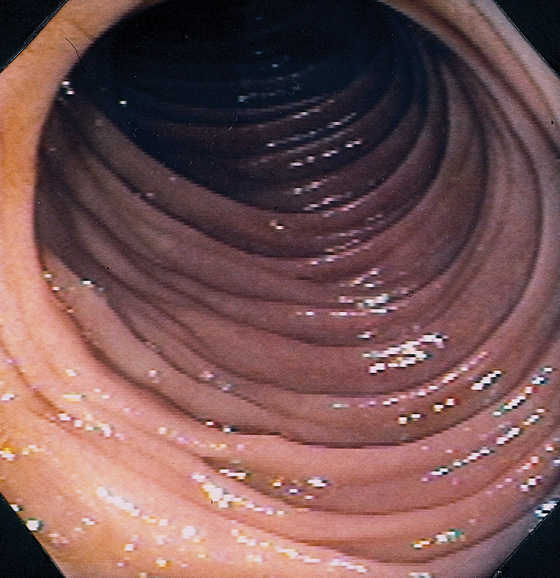

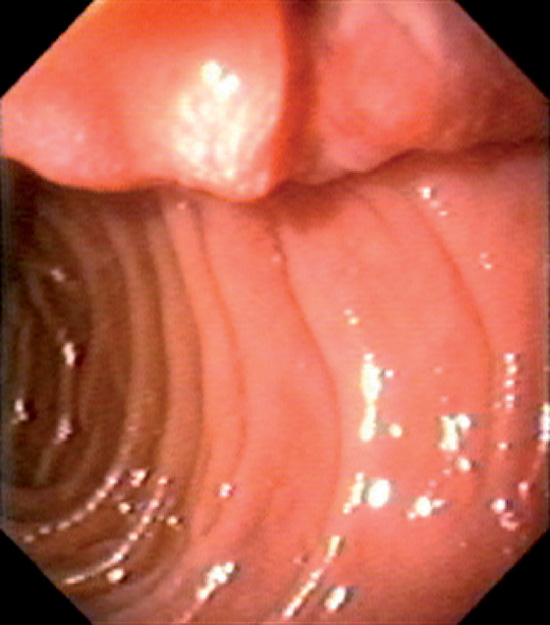

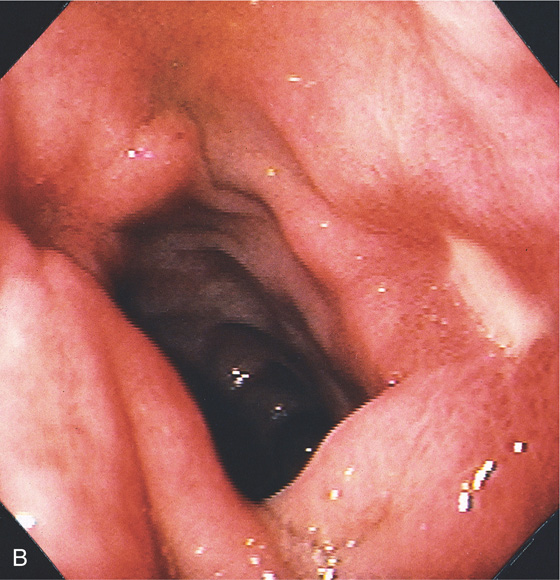

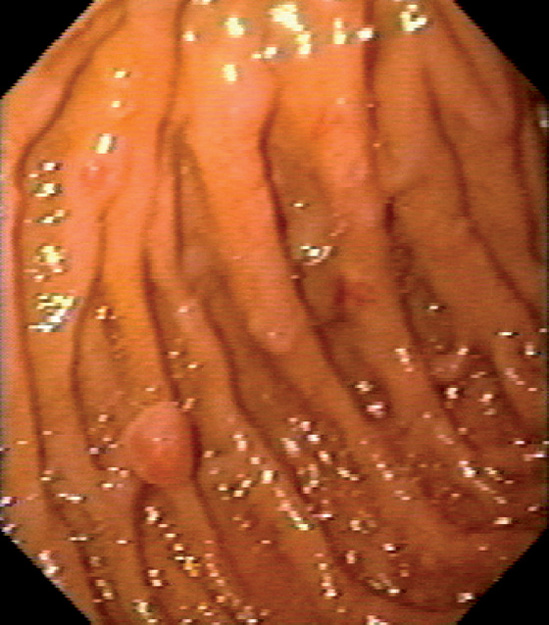

Figure 4.5 JEJUNUM

The jejunum is characterized by thinner but more frequent circular folds than in the duodenum, and the mucosa is smoother.

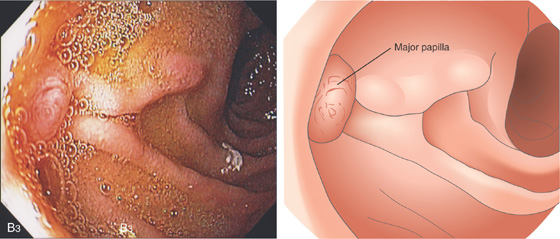

Figure 4.6 TERMINAL ILEUM

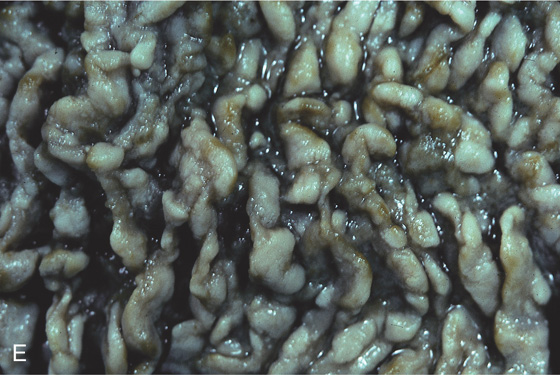

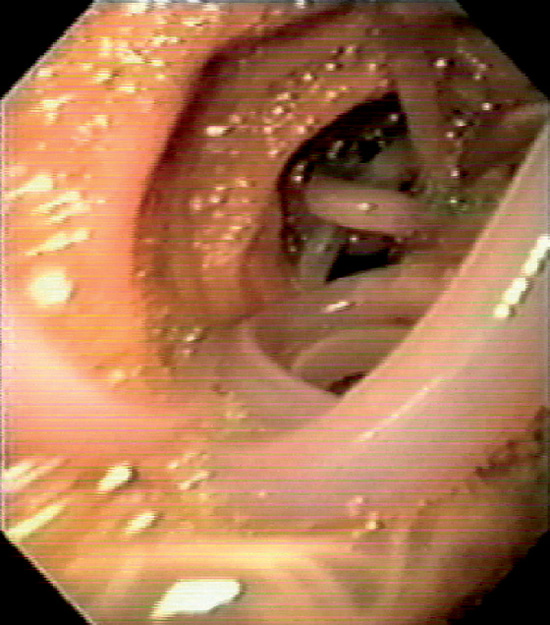

A, Reflux of barium on enema examination. B, Small-bowel follow-through. Barium also outlines the cecum. C, The mucosa has a finely granular appearance, and lymphoid follicles are present. D1, The mucosa has a fine, granular appearance. As visualized underwater, the villi can now be appreciated (D2). E, Prominent villi are noted in this patient.

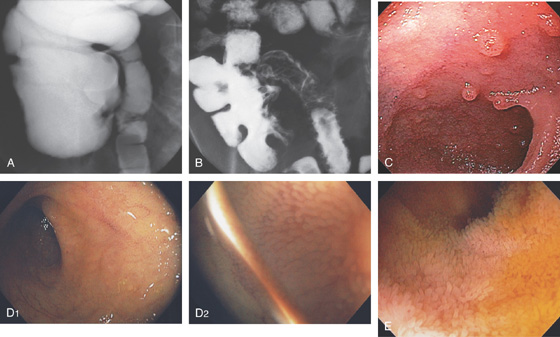

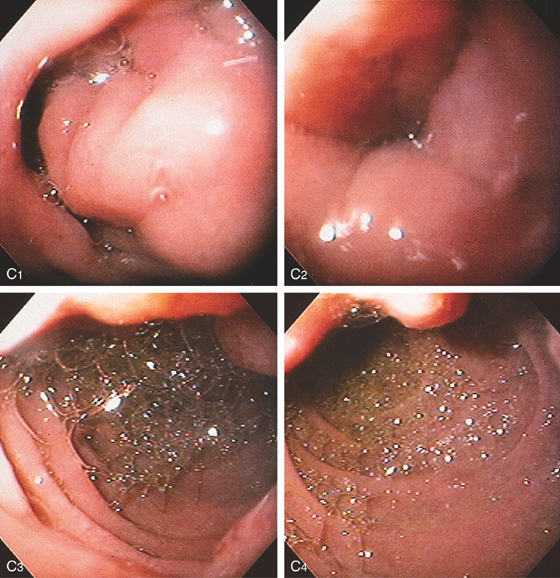

Figure 4.7 LYMPHOID HYPERPLASIA

A, Marked nodularity of the terminal ileum, as shown by reflux of barium during barium enema examination. B, Multiple well-circumscribed nodules. Lymphoid hyperplasia in the distal terminal ileum is a normal finding, frequent in younger persons.

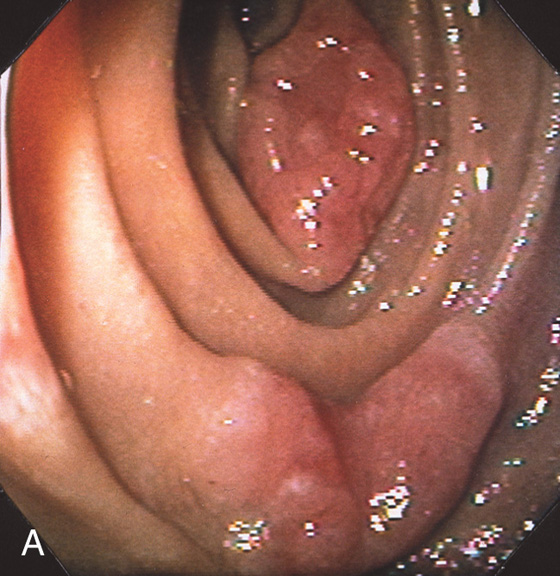

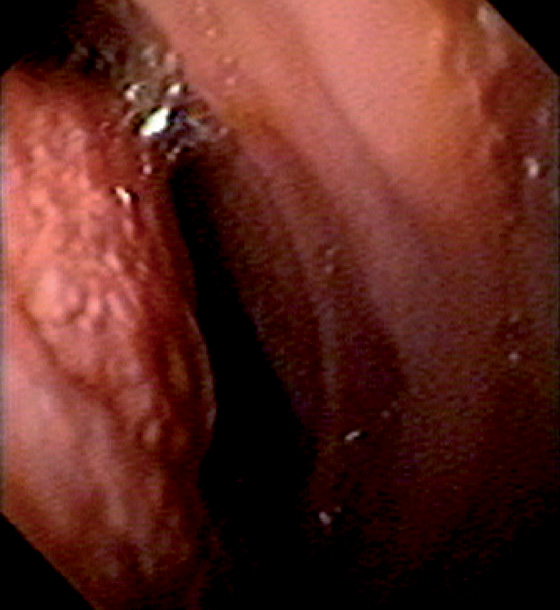

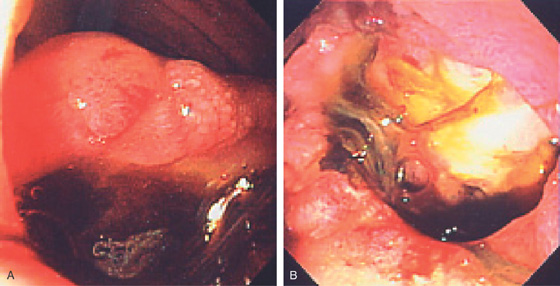

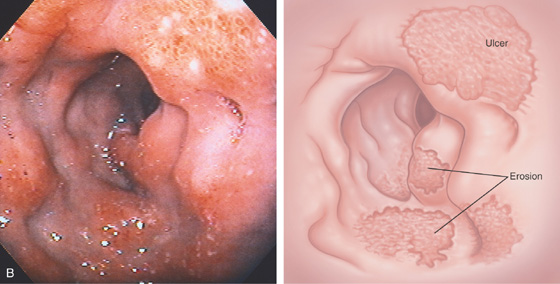

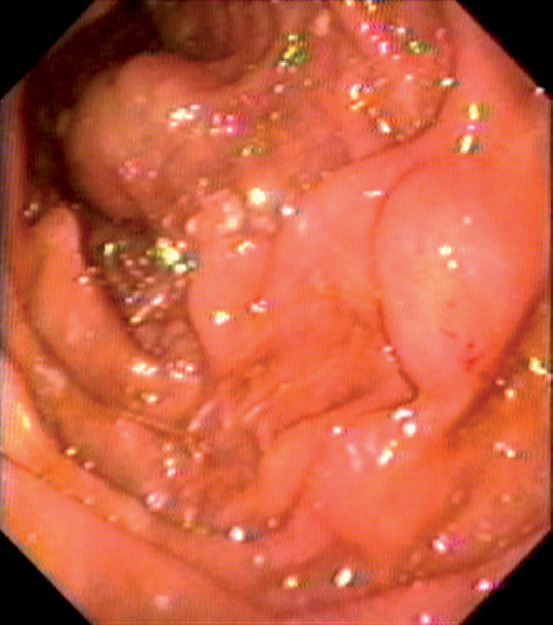

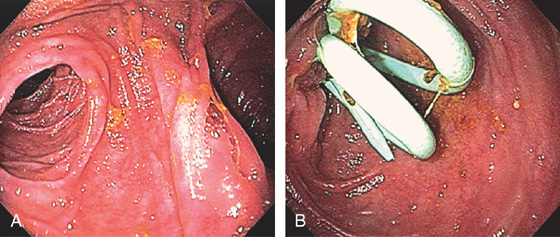

Figure 4.8 EROSIVE DUODENITIS

Multiple erosions in the duodenal bulb.

Figure 4.9 EROSIVE DUODENITIS

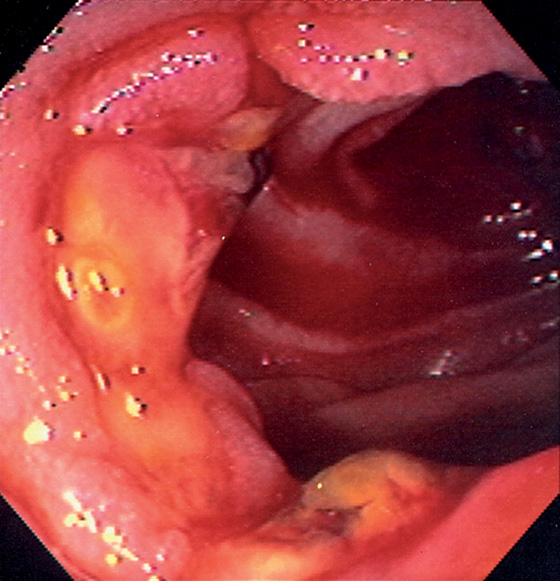

A, Marked nodularity of duodenal bulb. B, Severe edema, subepithelial hemorrhage, and multiple erosions. A portion of an active crater is present.

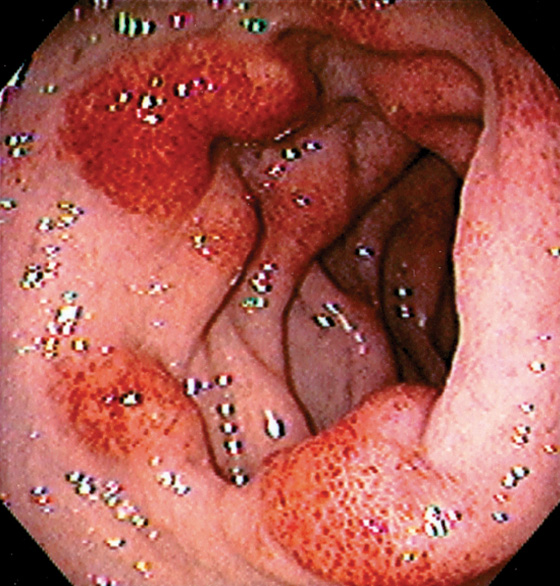

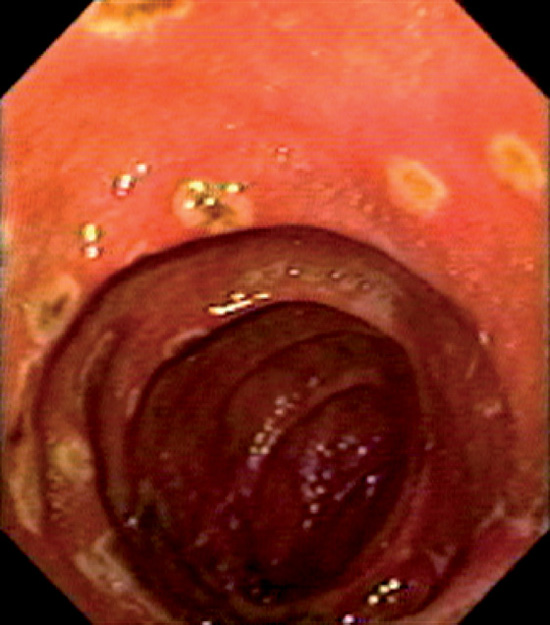

Figure 4.10 HEMORRHAGIC DUODENITIS

Patchy subepithelial hemorrhage in the distal duodenal bulb.

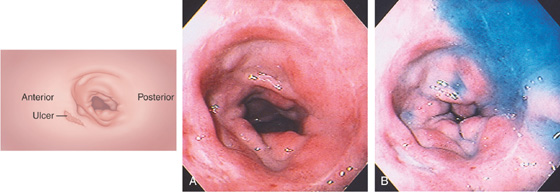

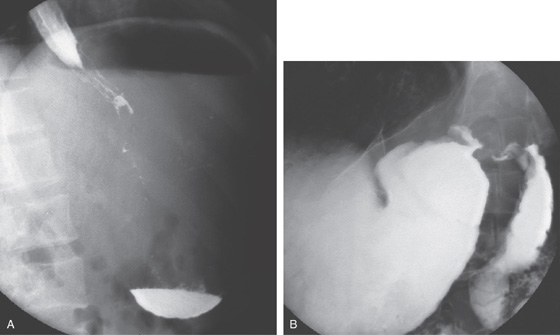

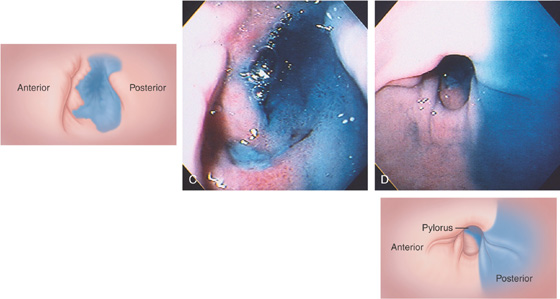

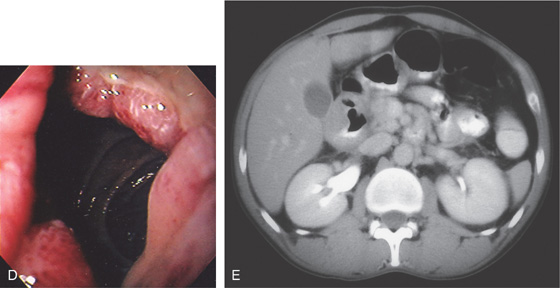

Figure 4.11 DUODENAL ULCER

A duodenal ulcer is shown anteroinferiorly (A). Methylene blue has been placed in the bulb with the patient still in the left lateral decubitus position (B).

If the patient is moved to the supine position, fluid collects posteriorly, confirming the position in the bulb (C). The posterior portion of the antrum is demarcated by methylene blue (D).

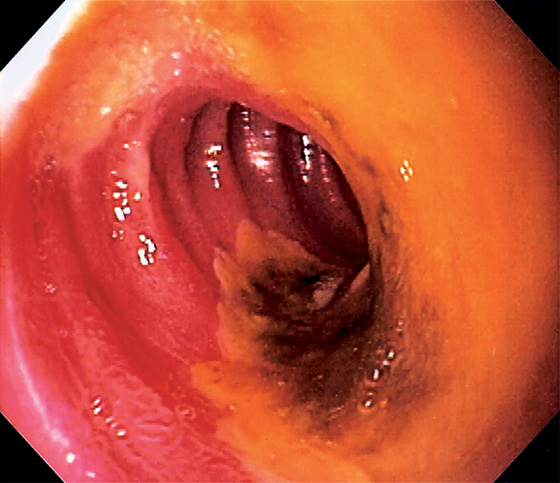

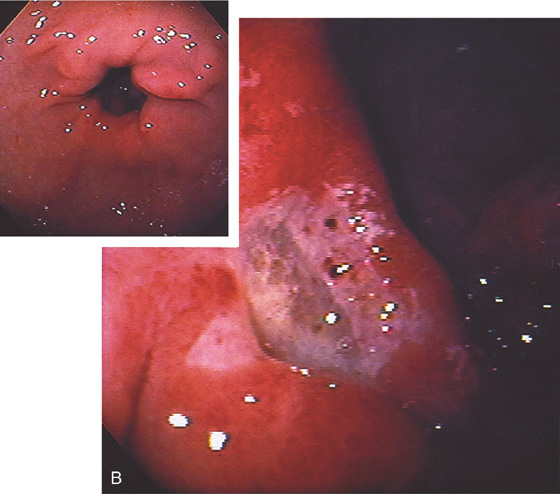

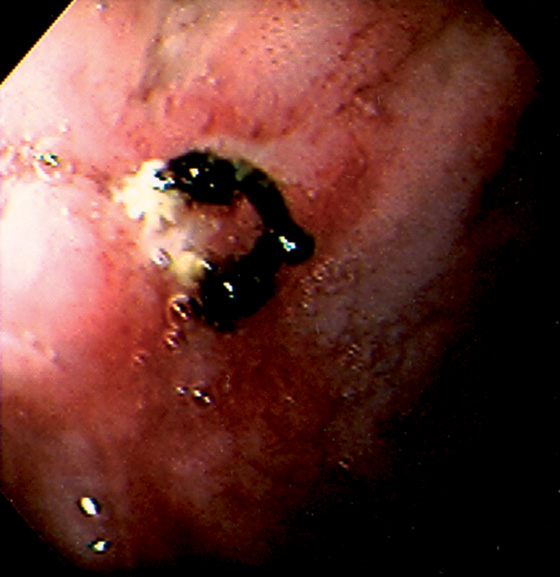

Figure 4.12 DUODENAL ULCER

A, Anterior clean-based duodenal ulcer. The duodenal folds are markedly edematous at the superior duodenal angle. A speckled pattern is on the gastric body, suggesting gastritis (inset, top). The antrum appears normal endoscopically (inset, bottom). Helicobacter pylori chronic active gastritis was histologically identified in both the body and the antral mucosa.

B, Deep anterior ulcer with multiple black spots in the ulcer base, suggesting recent bleeding. The ulcer margins are edematous and hemorrhagic. The antrum and peripyloric area show mild erythema and subepithelial hemorrhage, especially around the pylorus, suggesting gastritis (inset). H. pylori chronic active gastritis was found on antral biopsy.

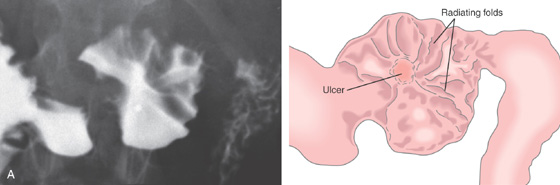

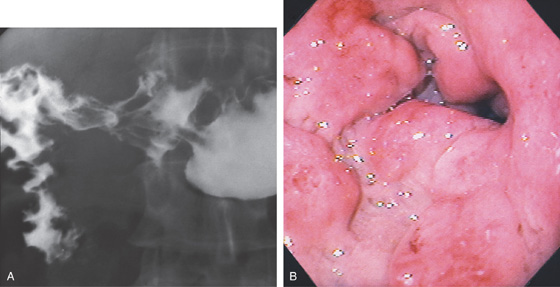

Figure 4.13 DUODENAL ULCER

A, A persistent collection of barium with radiating folds in the duodenal bulb, highly suggestive of an ulcer.

B, Posterior duodenal ulcer with a clean base. There is marked edema of the bulb, with folds radiating from the ulcer. Subepithelial hemorrhage is surrounding the ulcer, as well as in the remainder of the bulb. A small ulcerative lesion is also shown anteriorly.

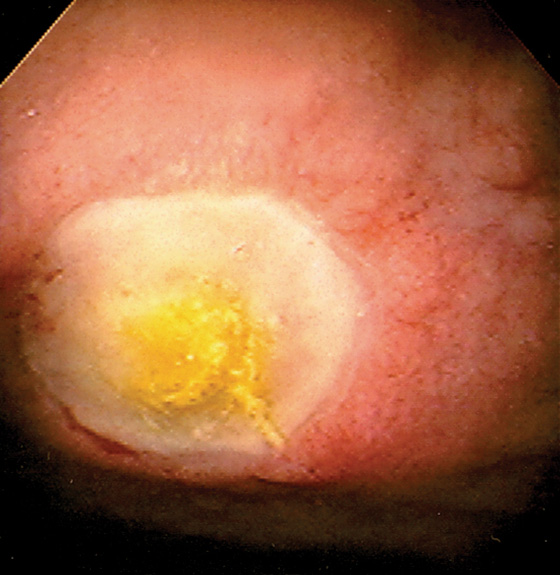

Figure 4.14 DUODENAL ULCER

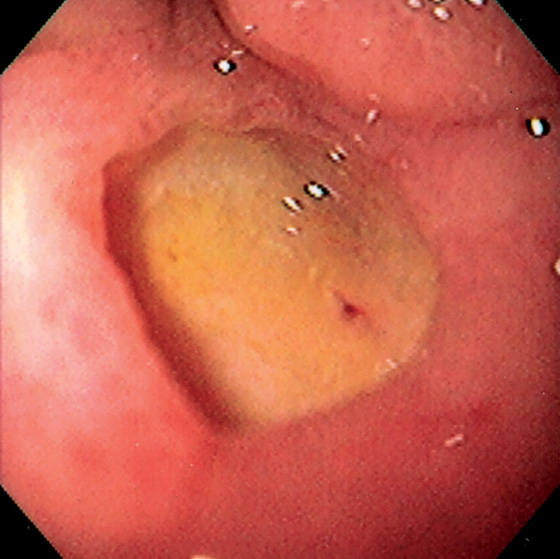

Well-circumscribed ulcer with yellow exudate resembling a fried egg.

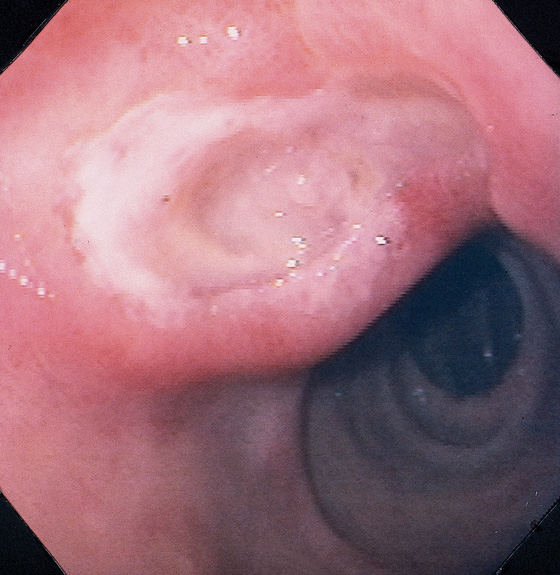

Figure 4.15 DUODENAL ULCER

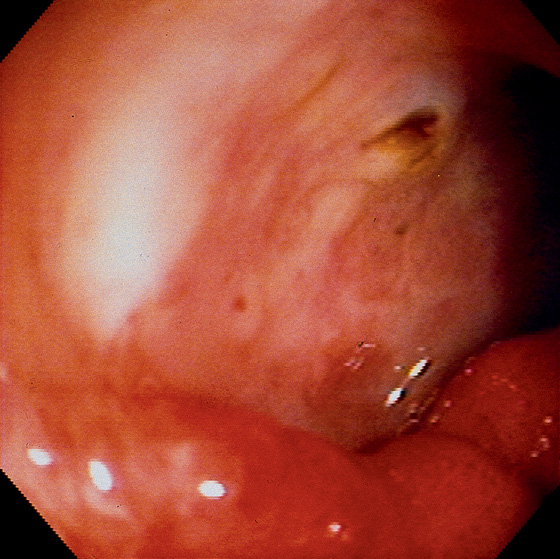

Large duodenal ulcer with surrounding edema projecting into the duodenal bulb. The second duodenum is normal.

Figure 4.16 DUODENAL ULCER

Small, clean-based ulcer surrounded by prominent folds and diffuse subepithelial hemorrhage.

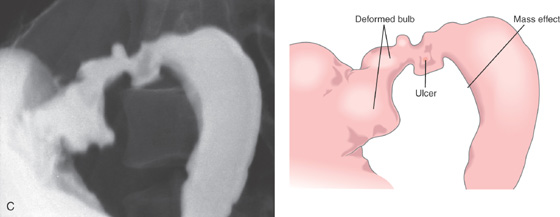

Figure 4.17 DUODENAL ULCER WITH SCARRING

Duodenal ulcer with several lesions and marked retraction resulting from prior disease.

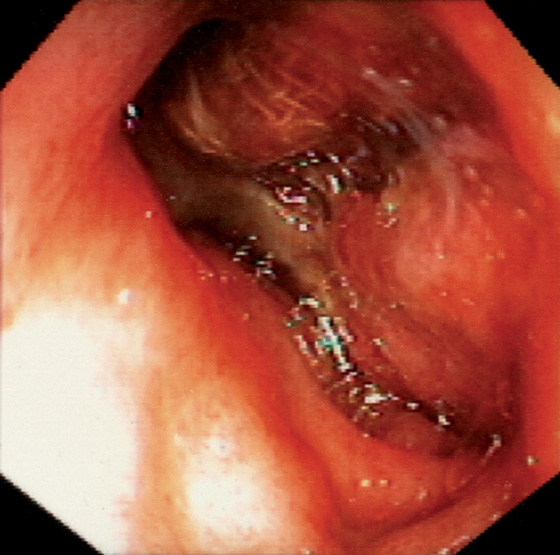

Figure 4.18 ANTERIOR SUTURE WITH SMALL ULCER

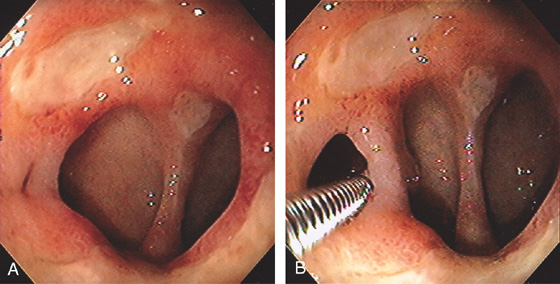

Suture at the site of a prior oversew of duodenal ulcer hemorrhage. Small ulceration is seen at the base of the suture material.

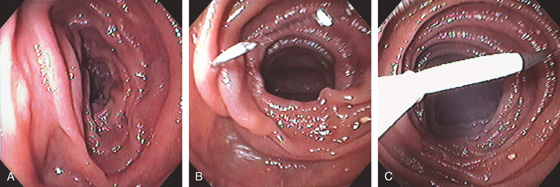

Figure 4.19 DUODENAL ULCER WITH DEFORMITY

A, Markedly abnormal duodenal bulb with active ulceration and pseudodiverticula. B, Forceps were placed in the slitlike opening demonstrating a mucosal bridge.

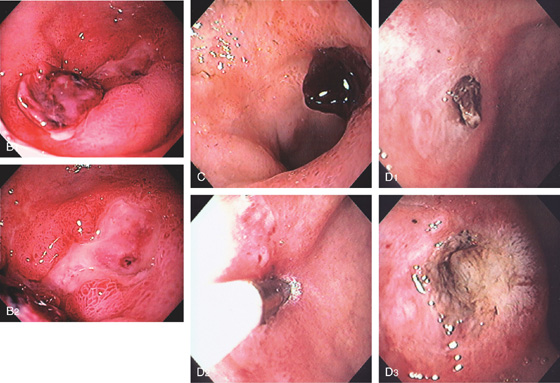

Figure 4.20 MALIGNANT DUODENAL ULCER

A, Edematous fold posteriorly at the junction of the first and second duodenum. There is mild narrowing and associated ulceration anteriorly. B, The ulceration is surrounded by edematous duodenal tissue. C, The depth of the lesion is evident. Biopsy results proved adenocarcinoma, and this patient had a hilar mass (cholangiocarcinoma).

![]() Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Duodenal Ulcer (Figure 4.20)

Benign duodenal ulcer

Extrinsic neoplasm (cholangiocarcinoma, pancreatic carcinoma)

Periduodenal inflammatory process (e.g., pancreatitis)

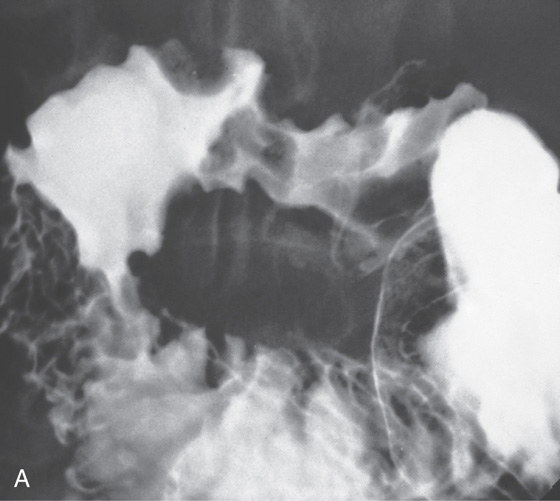

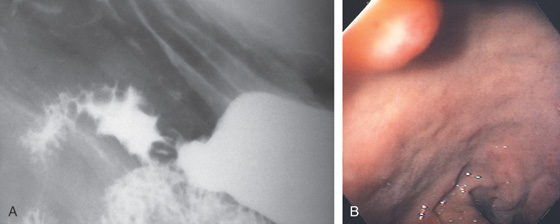

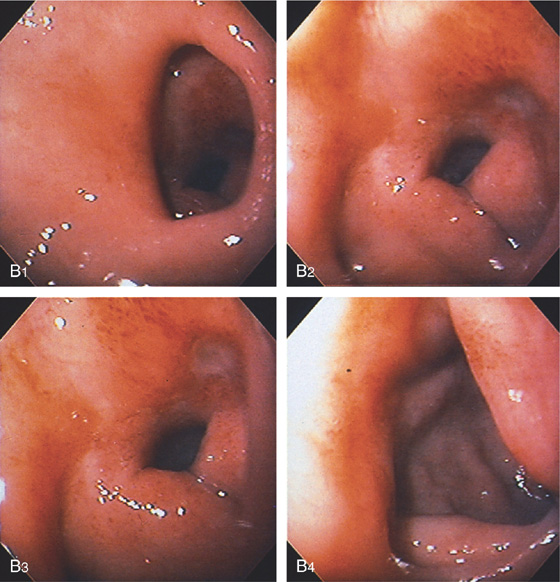

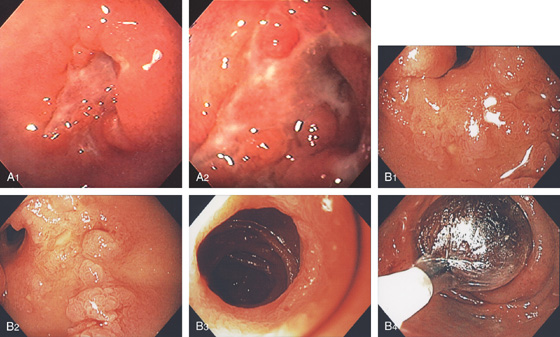

Figure 4.21 DUODENAL DEFORMITY MIMICKING ULCER

A, Collection of barium in the duodenal bulb with radiating folds, suggestive of an active ulcer crater. There is marked edema of the folds in the second duodenum, suggesting duodenitis. B, The collection of barium represents an old healed ulceration. The duodenal bulb is markedly distorted, with multiple erosions and edema. In a patient with prior ulcer disease, healed craters, and secondary pseudodiverticula, active ulcer craters may be difficult to distinguish radiographically from inactive healed disease.

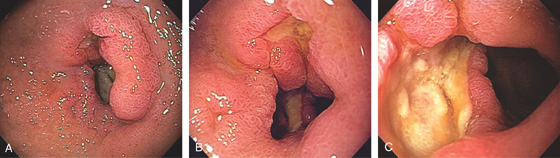

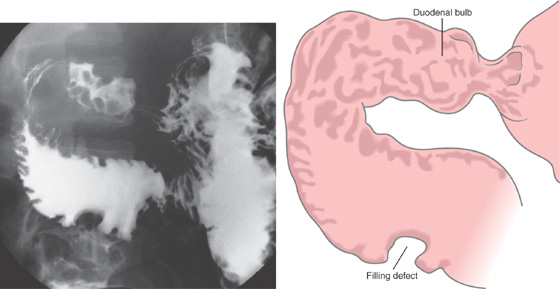

Figure 4.22 DUODENAL DEFORMITY MIMICKING POLYP

A, Filling defect in duodenal bulb mimicking a polyp.

B, The pylorus is patulous (B1); the bulb is edematous, with an active crater (B2, B3). Marked deformity and edema are present at the junction of the first and second portion of the duodenum (B4).

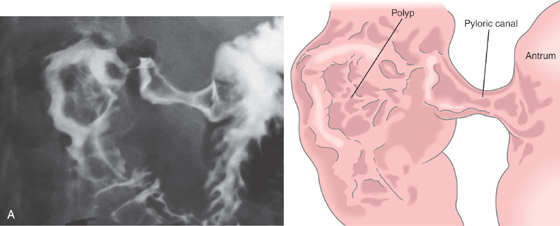

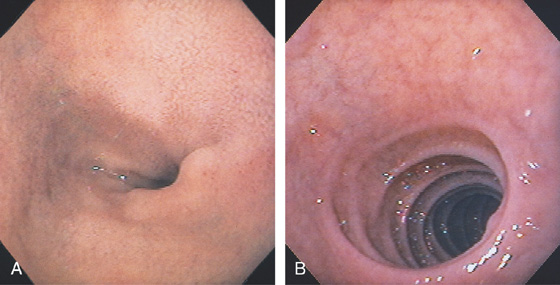

Figure 4.23 DOUBLE PYLORUS

A, Two openings at the pylorus separated by a mucosal bridge. B, The anterior opening is now more apparent when cannulated with a stiff wire. C, Upper gastrointestinal (UGI) series shows the two pathways to the duodenal bulb.

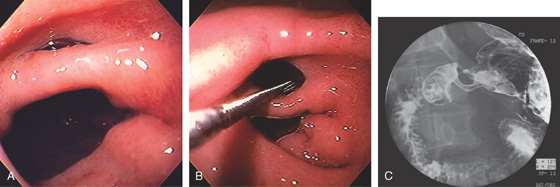

Figure 4.24 PYLORIC CHANNEL ULCER

A, The pylorus is seen with a clean-based ulcer posteriorly and a smaller ulcer anteriorly. There is associated subepithelial hemorrhage in the channel. A normal-appearing duodenal bulb and superior duodenal angle are seen in the distance.

Figure 4.24 PYLORIC CHANNEL ULCER

B, Mild narrowing of the pylorus with erythema and shallow posterior ulcer. C, Patulous pylorus with shallow ulcer both anteriorly and posteriorly.

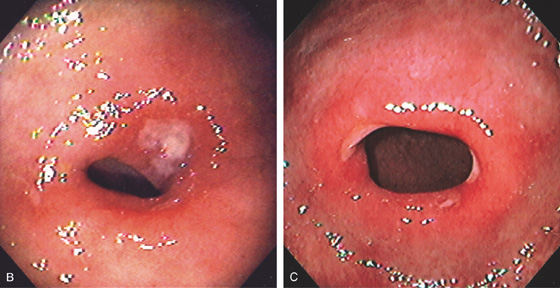

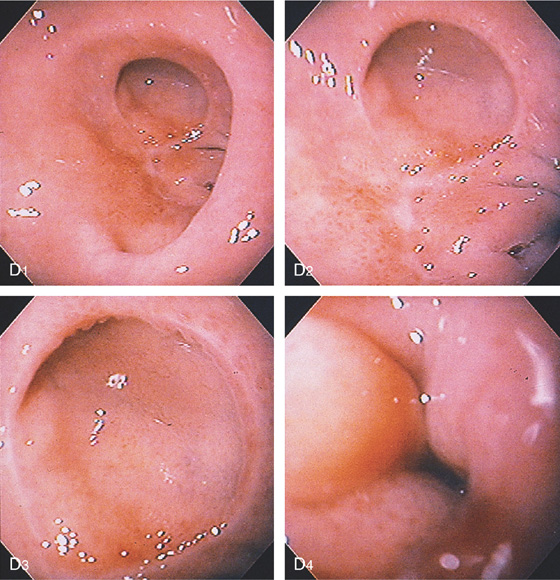

Figure 4.25 DUODENAL ULCER CAUSING GASTRIC OUTLET OBSTRUCTION

A, Markedly dilated, fluid-filled stomach, with barium seen in the distal esophagus and puddling in the gastric body. The gastric air bubble is pronounced. A succussion splash was present on physical examination. B, Deformity of the peripyloric area and bulb.

Figure 4.25 DUODENAL ULCER CAUSING GASTRIC OUTLET OBSTRUCTION

C, Deformity of bulb with active ulcer and edema, causing a mass effect on the proximal second duodenum.

D, The pylorus is absent. A large pseudodiverticulum is shown anteriorly (D1-D3). Edema and narrowing are present with further advancement of the endoscope (D4).

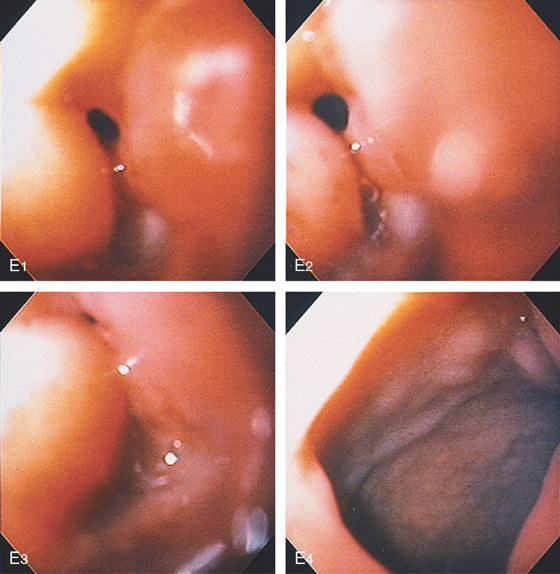

Figure 4.25 DUODENAL ULCER CAUSING GASTRIC OUTLET OBSTRUCTION

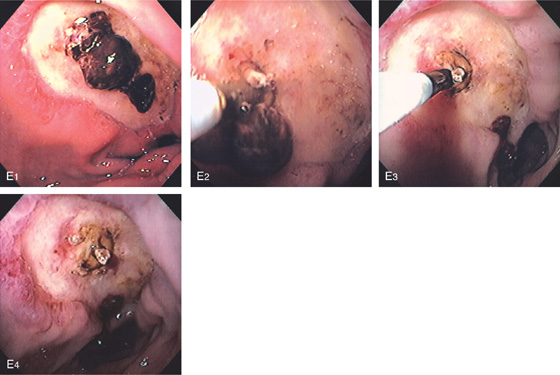

E, An ulcer is seen posteriorly (E1-E3). The circumferential process ends abruptly at the superior duodenal angle (E4).

Figure 4.26 ULCER IN DESCENDING DUODENUM

Large hemicircumferential bile-stained ulcer in the mid-second duodenum. The lesion was caused by nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug use.

Figure 4.27 ZOLLINGER-ELLISON SYNDROME

A, Edema and erythema at the junction of first and second duodenum associated with a small posterior ulcer. B, Giant ulcer in the second duodenum. C, Multiple ulcers in the mid-second duodenum. D, This patient also had severe erosive esophagitis. The association of esophagitis with ulcers in the second duodenum should raise suspicion for Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.

Figure 4.28 DUODENAL ULCER WITH FLAT RED SPOT

Large ulcer with flat red spot.

Figure 4.29 GIANT DUODENAL ULCER WITH RAISED SPOT

Note the depth of the lesion with the surrounding ulcer rim. A raised black spot in the center of the ulcer indicates the point of bleeding.

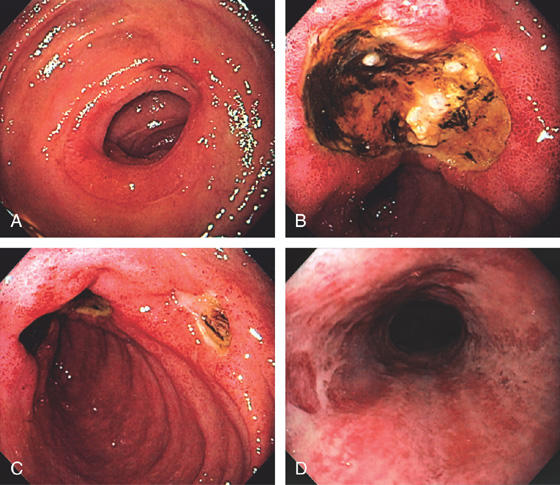

Figure 4.30 DUODENAL ULCER WITH BLACK BASE

A, Large posterior ulcer with heaped-up margins and adherent heme. B, Well-circumscribed posterior ulcer partially covered by old blood. C, Anterior duodenal ulcer with black base. Note the nearby small, clean-based ulcer.

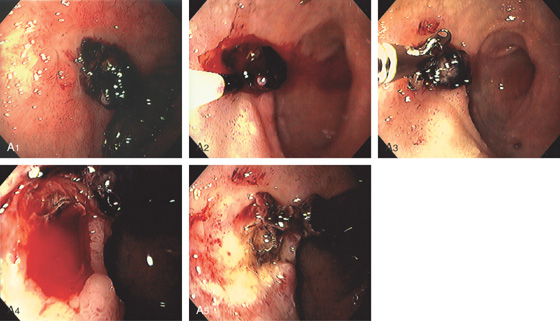

Figure 4.31 DUODENAL ULCER WITH CLOT

A1, Anterior ulcer with protruding adherent clot. A2, Epinephrine is injected into the base of the clot with bleeding precipitated. A3, The clot is removed with biopsy forceps. Note the ischemic appearance of the duodenum resulting from the epinephrine injection. A4, Oozing was seen from fleshy material at the base of the clot representing a visible vessel. A5, Thermal therapy was applied to the bleeding area, resulting in black eschar with depth and hemostasis achieved.

Figure 4.31 DUODENAL ULCER WITH CLOT

B, Deep serpiginous ulcer with adherent clot proximally and flat black spot distally. C, Adherent clot to a posterior ulcer. D1, Shallow anterior ulcer with small adherent clot. D2, 7-French heater probe applied to the clot. D3, Depression with black eschar after successful ablation of the area of clot.

E1, Large ulcer with central adherent clot. E2, The clot was manipulated with the thermal probe, resulting in dislodgement and exposure of fleshy material, presumably visible vessel. E3, Dilute epinephrine is injected into the base of the fleshy material. Note the dislodged clot in the distance. E4, After injection, there is marked ischemia of the anterior duodenum.

Figure 4.32 MASS-LIKE DUODENAL ULCER WITH CLOT

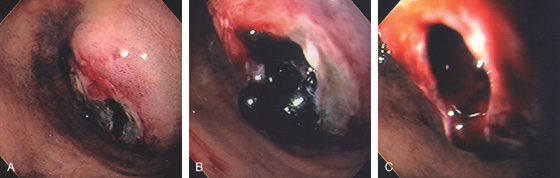

A, Mass effect in the posterior duodenum with central ulceration. B, Close-up of the ulcerated area demonstrates an opening covered with clot. C, With clot removed, a cavity is evident.

D, More distally, circumferential ulcer is seen with normal duodenum in the distance. E, Marked circumferential thickening of the duodenum resembling a mass lesion. Air is seen in the lumen and in the thickened wall. Surgery confirmed a benign duodenal ulcer.

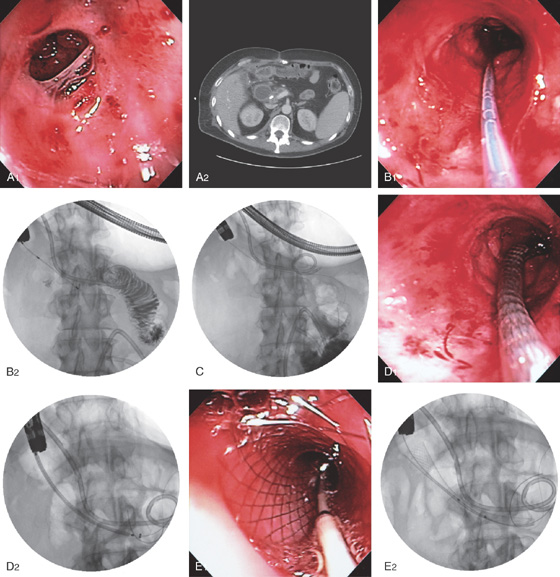

Figure 4.33 MALIGNANT DUODENAL ULCER WITH BLEEDING VISIBLE VESSEL

A, Large ulcer in the anterior wall of the duodenal bulb. Note the mass effect in the duodenum and the lack of well-defined edges to the ulcer. There is a central fresh blood clot with active oozing from underneath. B, Thermal therapy was applied to the area, resulting in eschar and depression. Subsequent biopsy results showed adenocarcinoma.

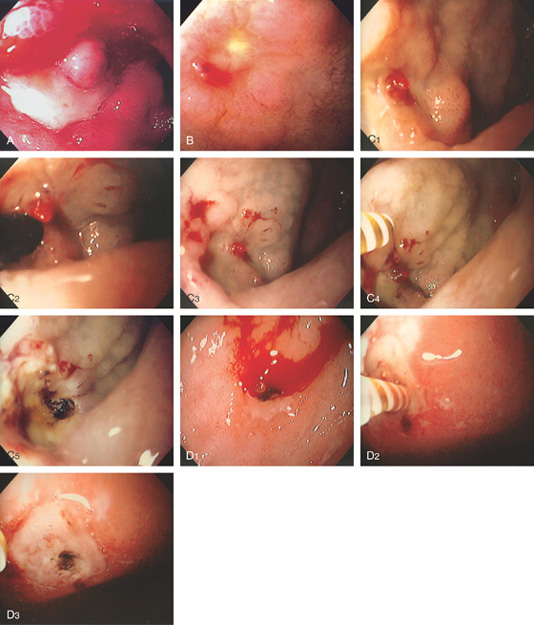

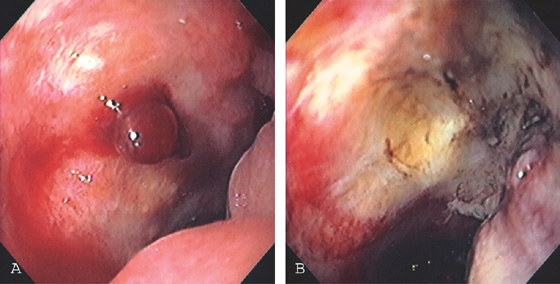

Figure 4.34 DUODENAL ULCER WITH VISIBLE VESSEL

A, Large ulcer with central protrusion and fresh bleeding. The protrusion was seen to pulsate (an artery), and no endoscopic therapy was thus performed. B, Small ulcer with fleshy visible vessel at the proximal margin with a small adherent red clot. C1, Red nipple extending from a small anterior duodenal ulcer. C2, Dilute epinephrine is injected just inferior to the nipple. C3, Note the marked blanching after epinephrine injection. C4, A thermal probe is approaching the vessel. C5, Black eschar and cavitation resulting from thermal therapy. D1, Visible vessel in a small duodenal ulcer with active arterial bleeding. D2, Thermal therapy is applied directly to the bleeding point. D3, Black eschar at the site of thermal therapy and resultant hemostasis.

Figure 4.35 DUODENAL ULCER WITH VISIBLE VESSEL AND ARTERIAL BLEEDING

A, Large anterior duodenal ulcer with fleshy nonbleeding visible vessel. B, With observation, active arterial bleeding began. C, Appearance of the ulcer after thermal therapy.

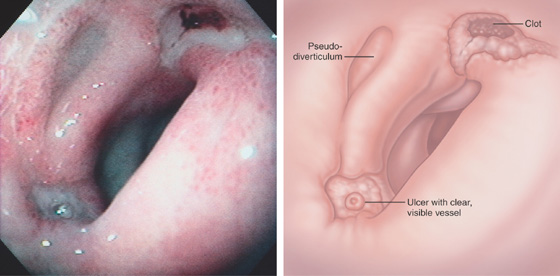

Figure 4.36 DUODENAL ULCERS WITH MULTIPLE STIGMATA

Two ulcers in the bulb with associated pseudodiverticulum. The anteroinferior ulcer has a white nipple-like projection, whereas the superior ulcer has a large, flat black area.

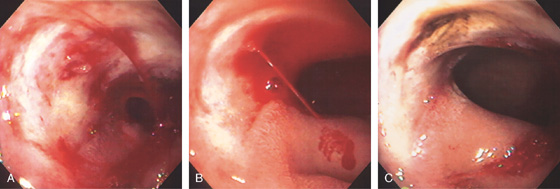

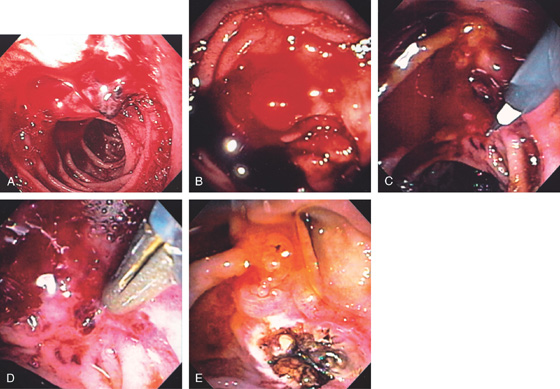

Figure 4.37 BLEEDING ULCER IN SECOND DUODENUM

A, Fresh blood and active bleeding from a clot in the second duodenum. Because of the position, a forward viewing endoscope could not adequately visualize the area for endoscopic therapy. B, Bleeding area as seen with side viewing duodenoscope. An en face view was now possible. C, With vigorous washing, a focal area of bleeding was seen and dilute epinephrine injected with a sclerotherapy needle. D, After epinephrine therapy, a fleshy vessel was identified. The 10-French thermal probe is in position. Multiple pulses were applied, resulting in hemostasis and a black eschar. E, Note bile flowing from the major papilla just superior to the lesion.

Figure 4.38 DUODENAL ULCER PERFORATION

Large duodenal ulcer with apparent opening. Surgery confirmed a perforated anterior ulcer.

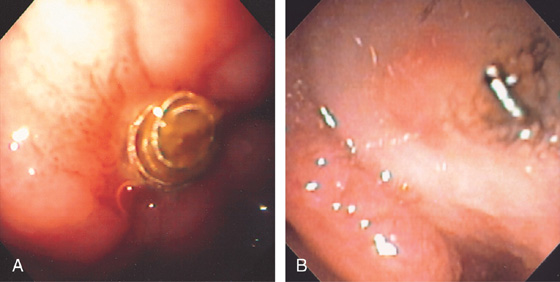

Figure 4.39 COILS IN DUODENAL WALL FROM PRIOR EMBOLIZATION

A, B, Round coils at site of prior bleeding ulcer.

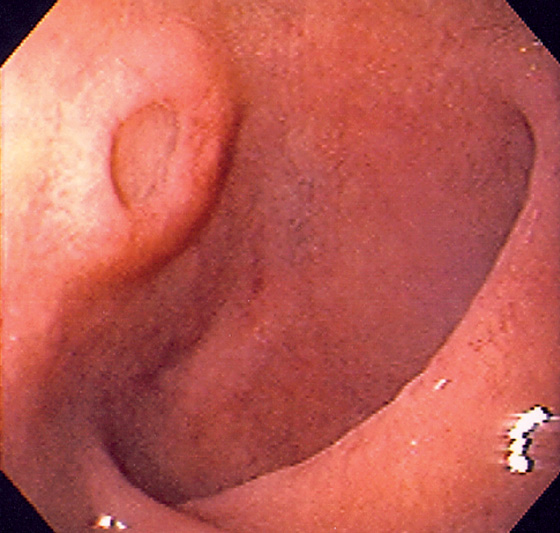

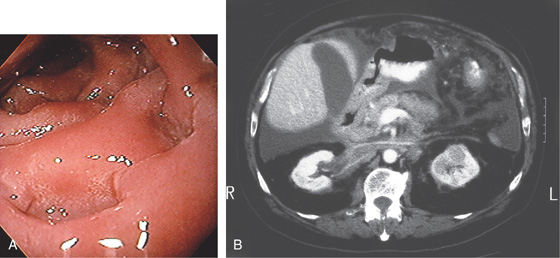

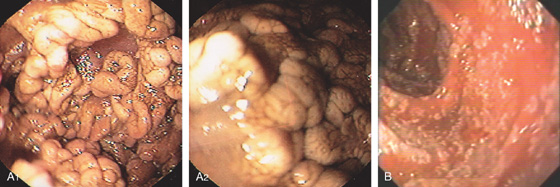

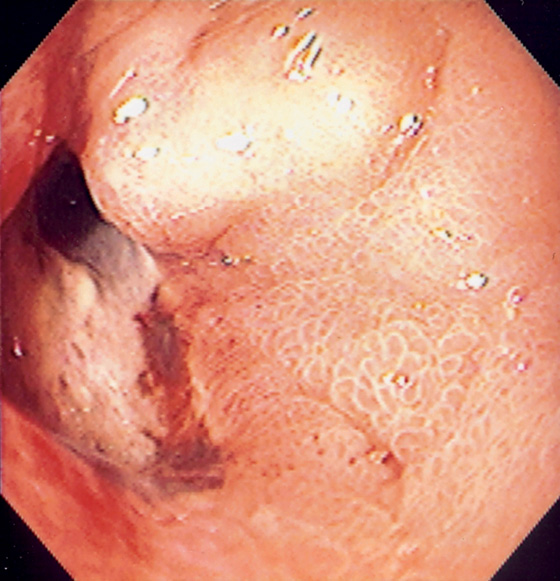

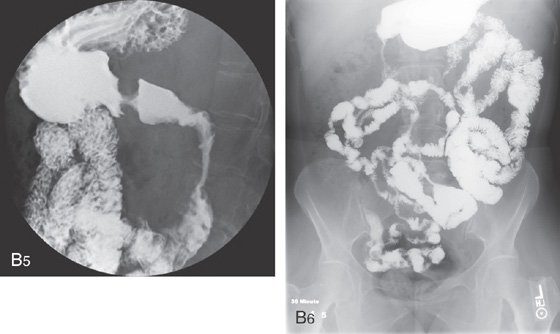

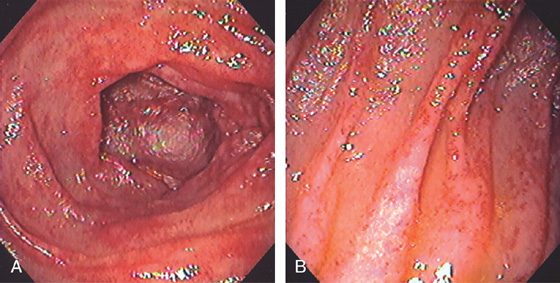

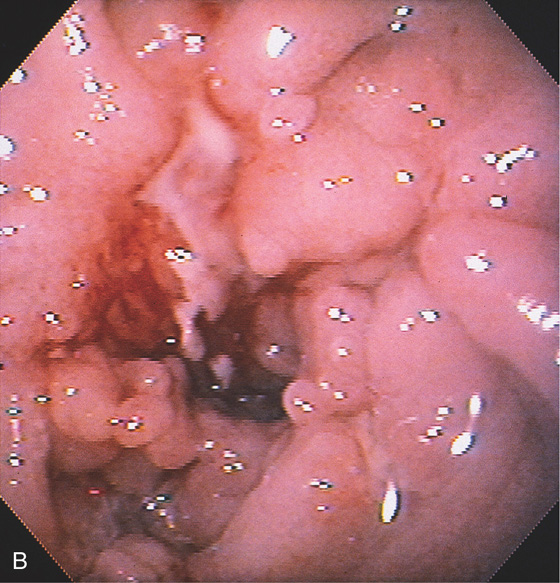

Figure 4.40 CROHN’S DISEASE

A1, Irregular ulceration at the junction of first and second duodenum. A2, Close-up shows the serpiginous nature of the ulcer. B1, B2, Serpiginous ulceration with nodularity in the third duodenum with some narrowing. B3, More distally, a stricture is shown. B4, Balloon dilatation of the stricture.

B5, B6, UGI series with a small-bowel follow-through shows multiple strictures and distal ileal disease confirming the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease.

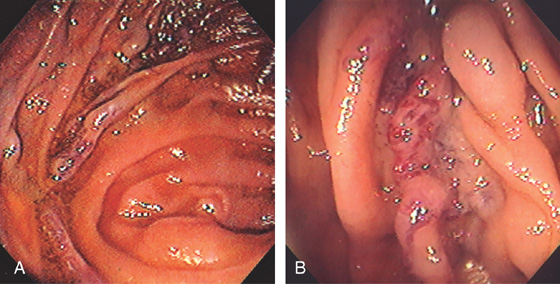

Figure 4.41 JEJUNAL CROHN’S DISEASE

Ulcerated stricture in the proximal jejunum found by push enteroscopy. (Courtesy F. Perez-Roldan, MD, and P. Gonzalez-Carro, MD, Alcazar de San Juan, Spain.)

Figure 4.42 ISCHEMIA

Serpiginous ulceration throughout the second duodenum.

Figure 4.43 INFARCTION

A, Thick exudate covers the duodenum. B1, B2, When the exudate is débrided, the underlying mucosa is black and necrotic.

Figure 4.44 VASCULAR ECTASIA

A, Air has been withdrawn from the duodenal bulb to bring the ectasia closer, documenting the lack of depth and the characteristic frondlike appearance. B1, Solitary ectasia in the second duodenum. B2, The ectasia is well delineated on narrow band imaging.

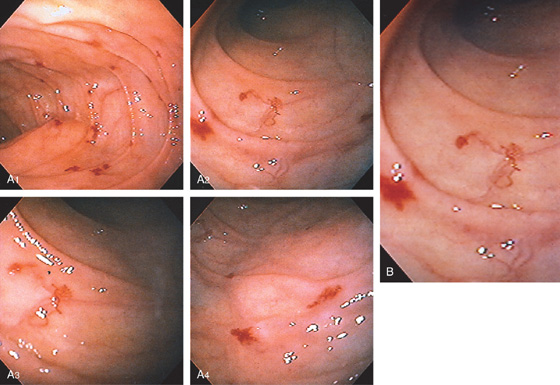

Figure 4.45 MULTIPLE VASCULAR ECTASIAS

A, Multiple ectasias in the second duodenum. Ectasias were not seen in the stomach or colon. B, Close-up view demonstrates the variable appearance of two ectasias.

Figure 4.46 BLEEDING ECTASIA UNDERWATER

A, A large amount of fresh blood in the mid-second duodenum without a pinpoint site. B, With infusion of water, blood was now seen to stream from a pinpoint site.

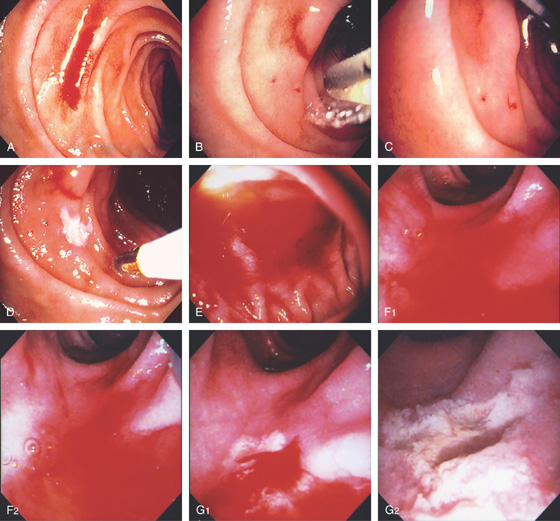

Figure 4.47 BLEEDING ECTASIA

A, A fresh stream of blood is shown. B, The heater probe water jet is applied to the bleeding area exposing a bleeding site. C, With observation, blood is seen to stream from a pinpoint ectasia. D, The 7-French heater probe is applied to the area, resulting in a white eschar and hemostasis. E, Fresh blood coating the proximal second duodenum with the forward viewing endoscope. No specific bleeding site is seen. F1, F2, Using the duodenoscope and with washing, an area of persistent oozing is seen. The area is vigorously washed identifying a pinpoint area whereby the heater probe is used to coagulate the lesion, resulting in exudate, white eschar, and hemostasis (G1, G2).

Figure 4.48 PORTAL HYPERTENSIVE DUODENOPATHY

A, Diffuse petechial lesions in the second duodenum. This patient also had esophageal varices. B, Multiple dilated capillaries in the submucosa.

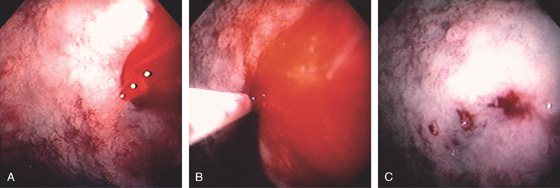

Figure 4.49 DIEULAFOY LESION

A, Active stream of blood jetting from the posterior duodenal bulb. B, Large volume of dilute epinephrine was injected into the bleeding site. C, After injection, the mucosa has a whitish appearance from ischemia. A pinpoint area representing the bleeding site is apparent.

Figure 4.50 RADIATION ENTERITIS

Multiple small ectasias throughout the duodenum after radiation therapy (A, B).

Figure 4.51 DUODENAL VARICES

A, Small submucosal veins. B, Gastric varices were also present. This patient had splenic vein thrombosis.

Figure 4.52 ANASTOMOTIC VARICES

A, Variceal trunk near the site of a small-bowel anastomosis. B, Close-up of the area shows subepithelial varices.

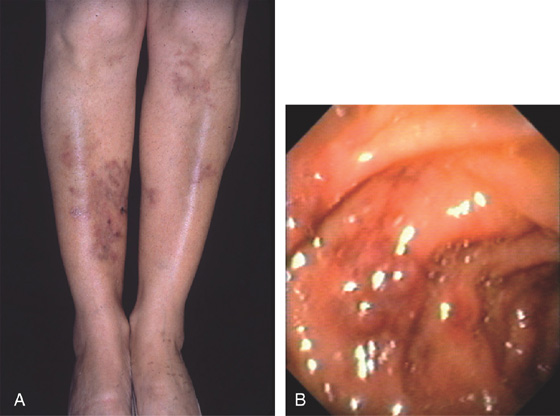

Figure 4.53 POLYARTERITIS NODOSA

A, Typical skin lesion on the lower extremities. B, Submucosal purpuric lesion of the duodenum. (A courtesy P. Redondo, MD, Pamplona, Spain.)

Figure 4.54 HENOCH-SCHÖNLEIN PURPURA

A, B, Focal petechial lesions in the second duodenum. The surrounding mucosa is normal.

Figure 4.55 THROMBOTIC THROMBOCYTOPENIC PURPURA

Multiple well-circumscribed erosions in the second duodenum.

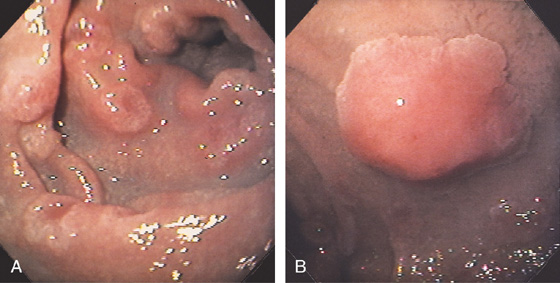

Figure 4.56 INFLAMMATORY POLYP

Two small, raised, polypoid lesions in the anterior duodenal bulb. Biopsy findings demonstrated acute and chronic inflammation without evidence of neoplasia. The appearance is not pathognomonic for any specific type of polypoid lesion.

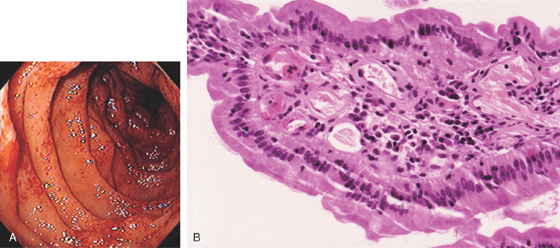

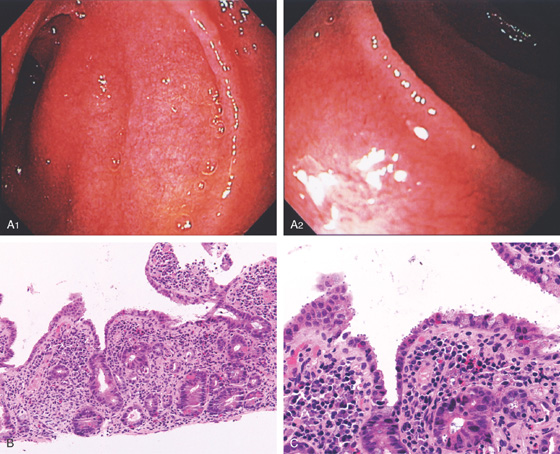

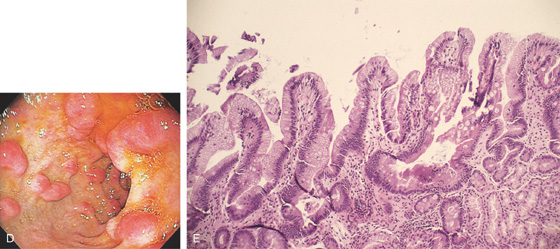

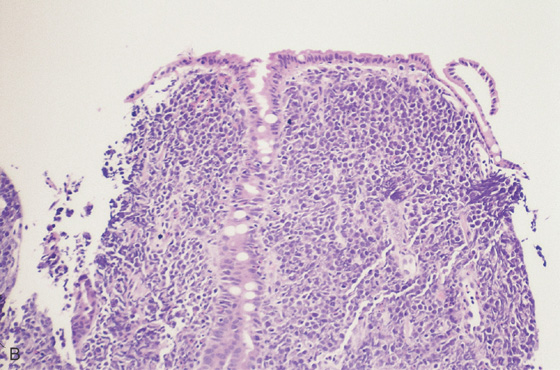

Figure 4.57 GASTRIC METAPLASIA

A, Multiple small nodules on the anterior wall of the duodenal bulb that have a typical appearance for gastric metaplasia. B, Larger lesions seen in association with the more typical smaller lesions. C, Larger polypoid lesions.

D, Linear polypoid lesions. E, Gastric-type mucosa with foveolar epithelium. Gastric metaplasia may be seen in the duodenal bulb, associated with polyps.

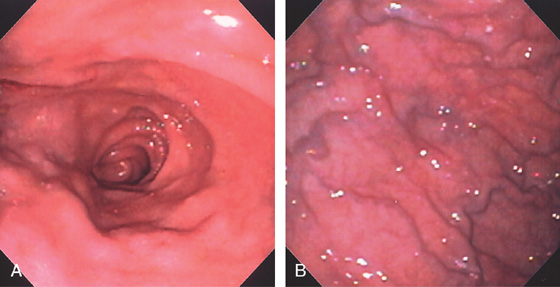

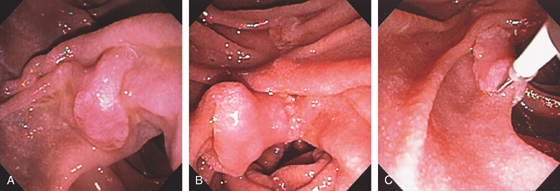

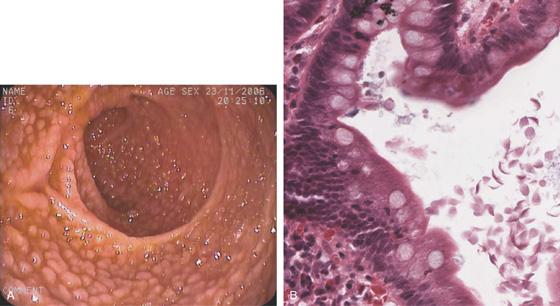

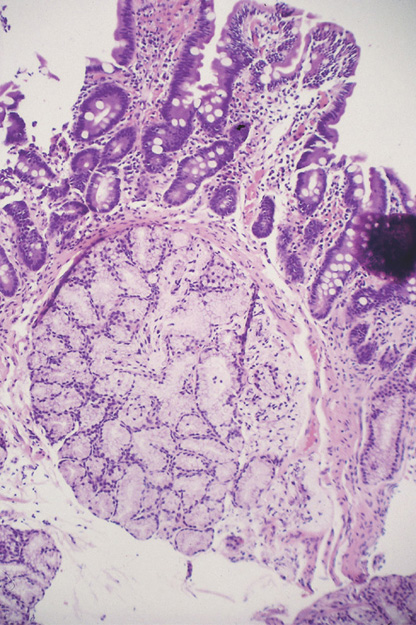

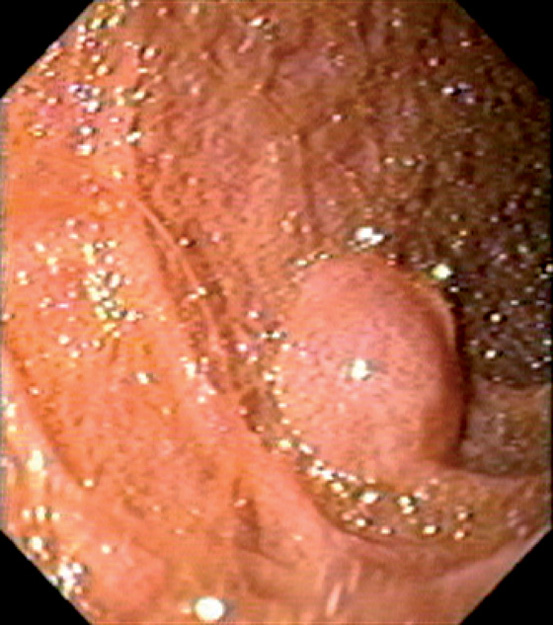

Figure 4.58 BRUNNER’S GLAND HYPERPLASIA

A, Small polypoid lesion in the duodenal bulb. B, Giant Brunner gland polyp.

C, Normal-appearing duodenal tissue with submucosal Brunner’s glands.

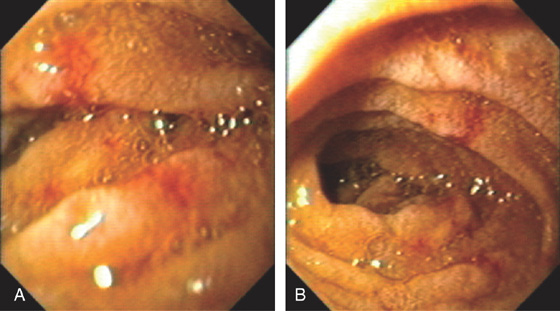

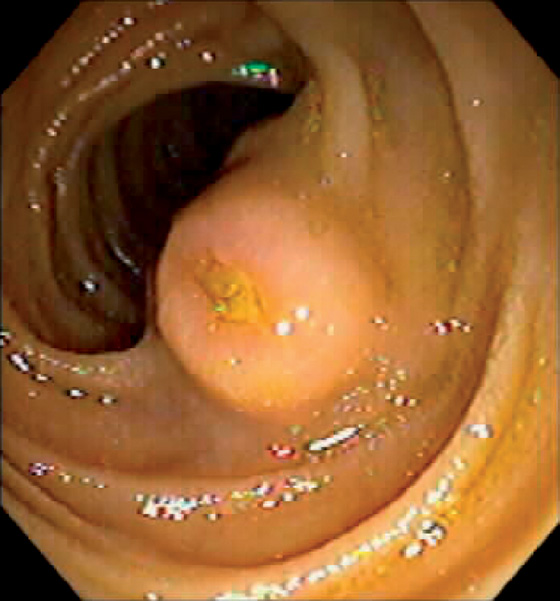

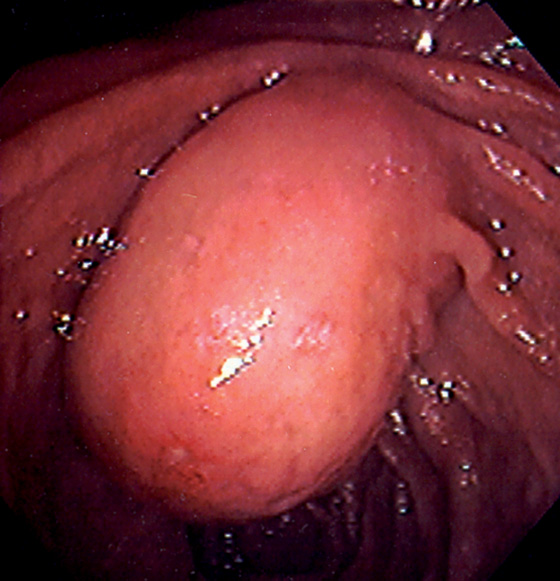

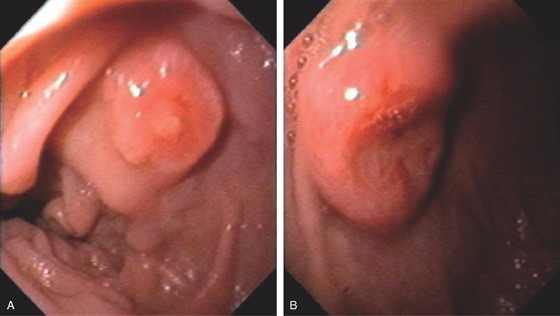

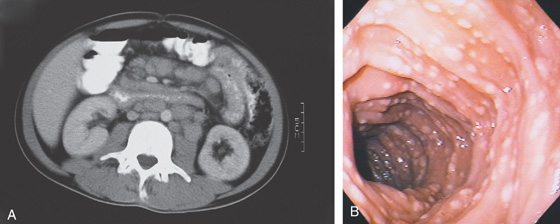

Figure 4.59 DUODENAL BRUNNER’S GLAND HAMARTOMA

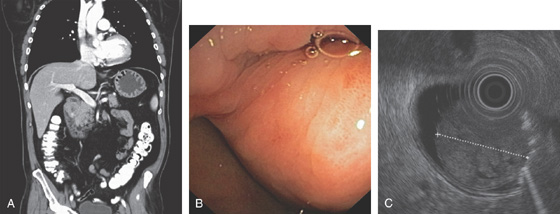

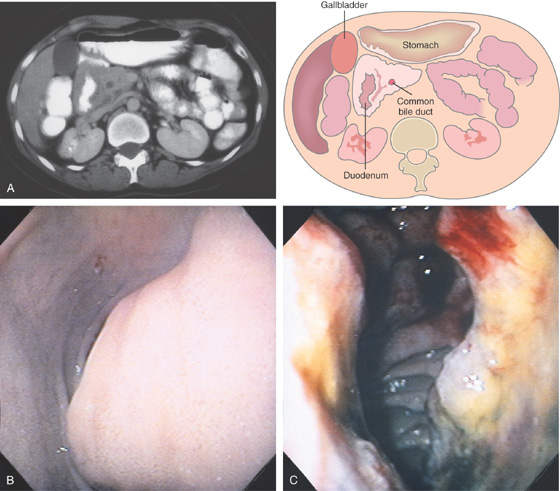

A, CT scan shows large duodenal mass lesion. B, Large, round lesion in the proximal second duodenum that appears submucosal. C, Endoscopic ultrasound shows the size of the lesion.

D, Histology demonstrates the Brunner’s glands. (Courtesy J. Pardo-Mindan, MD, Pamplona, Spain.)

![]() Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Duodenal Brunner’s Gland Hamartoma (Figure 4.59)

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor

Extrinsic lesion

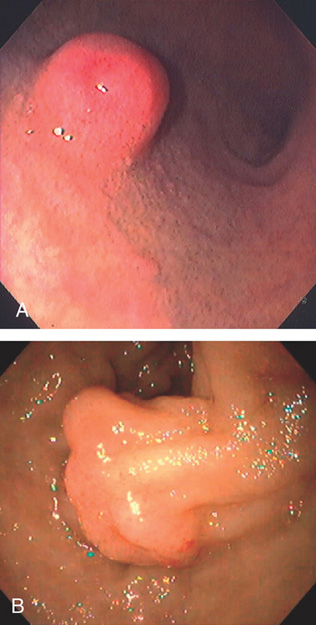

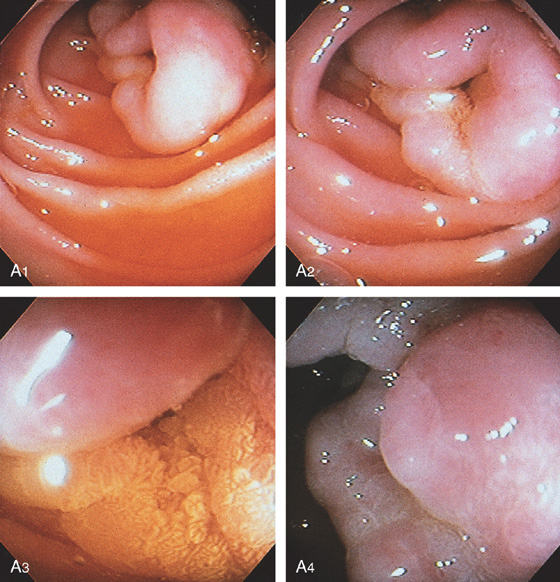

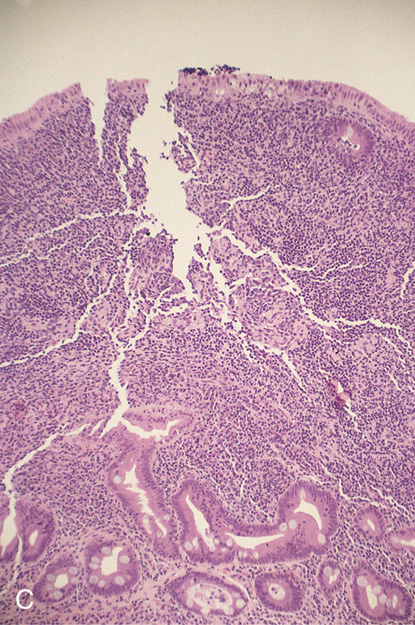

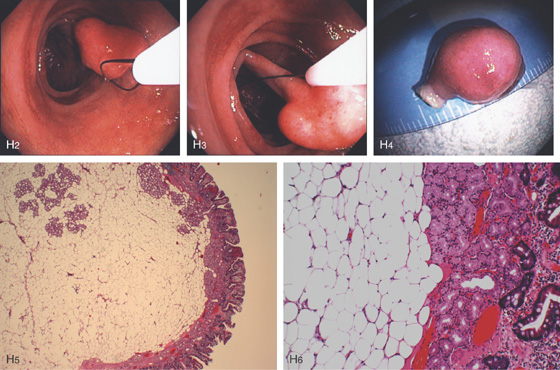

Figure 4.60 CARCINOID POLYP

A, Well-circumscribed lesion with central collection of barium in the proximal duodenal bulb. This lesion is more suggestive of an ulcer than a polyp. The duodenal bulb and second duodenum are normal. B, Polypoid lesion projecting from the anterosuperior duodenal bulb. A central area of indentation corresponding to the radiograph is not identifiable from this angle.

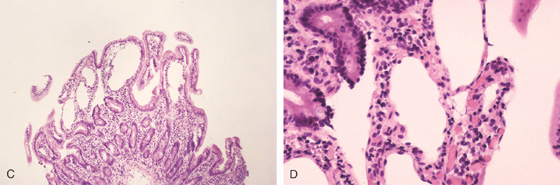

C, A monotonous population of small, round cells fills the lamina propria, compressing the normal duodenal glands.

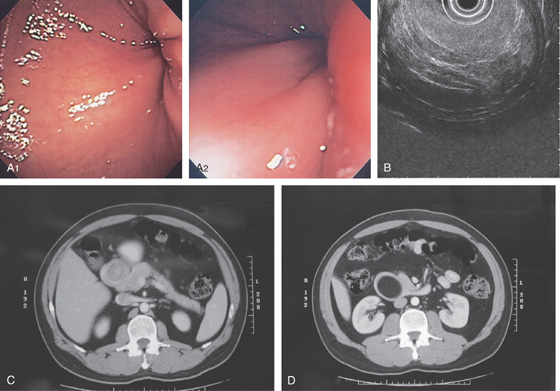

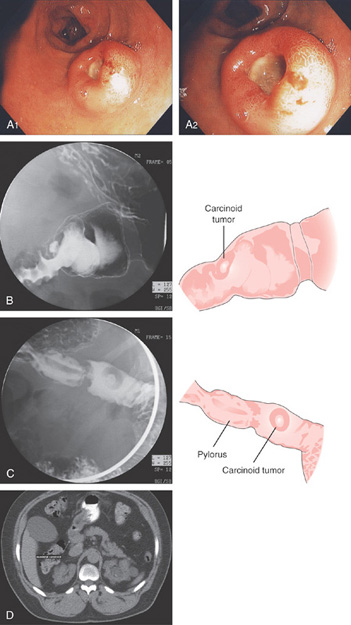

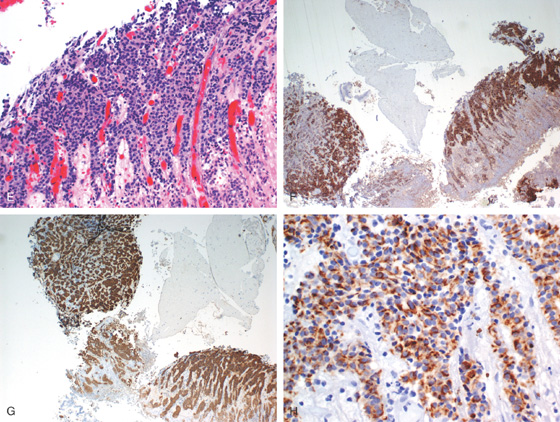

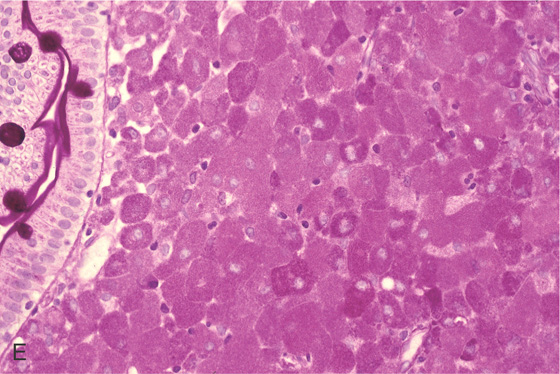

A1, A2, Round, donut-shaped lesion with central ulceration in the duodenal bulb typical for a neuroendocrine tumor. B, C, UGI series shows a defect in the duodenal bulb with persistent barium in the ulcer crater resembling the donut appearance (right). D, CT also shows the large filling defect represented by the hypodense lesion in the duodenum.

Figure 4.61 CARCINOID TUMOR

E, Carcinoid features are seen on routine hematoxylin and eosin staining. The neuroendocrine origin of the lesion is demonstrated by confirmational staining with chromogranin (F), synaptophysin (G), and keratin (H).

Figure 4.62 PANCREATIC REST

Well-circumscribed, donut-like lesion in the anterior duodenal bulb. This lesion resembles that seen in the stomach (see Figure 3.179).

Figure 4.63 DUPLICATION CYST

Large polypoid mass occupying the normal location of the ampulla. A small ulcer is on the inferior portion of the lesion.

![]() Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Duplication Cyst (Figure 4.63)

Primary ampullary adenocarcinoma

Other ampullary neoplasm

Impacted bile duct stone

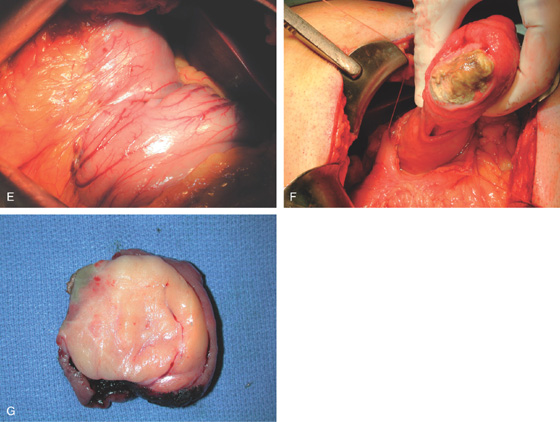

Figure 4.64 DUODENAL LIPOMA

A, Gastric mucosa appears to be pulled into the duodenum. B, On endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), a hyperechoic lesion is demonstrated. C, Intussusception as shown on CT. D, A mass occupies the duodenal lumen. The black color of the lesion represents a fat density on CT. E, Intussusception as seen at laparoscopy. F, The duodenum is open and the large lipoma demonstrated. G, The resection specimen confirms a fatty tumor.

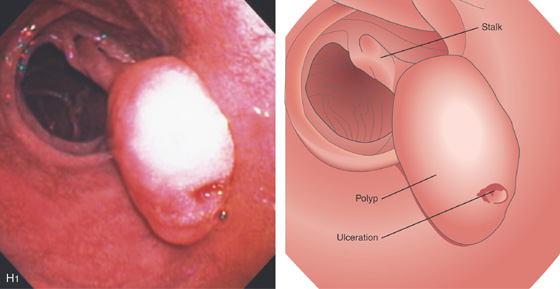

Figure 4.64 DUODENAL LIPOMA

H1, Polyp in duodenal bulb with a long stalk and with central ulceration.

H2, H3, The polyp is snared and resected, and measured to be 1cm (H4). H5, H6, Small-bowel mucosa with underlying well-circumscribed fibroadipose tissue mass.

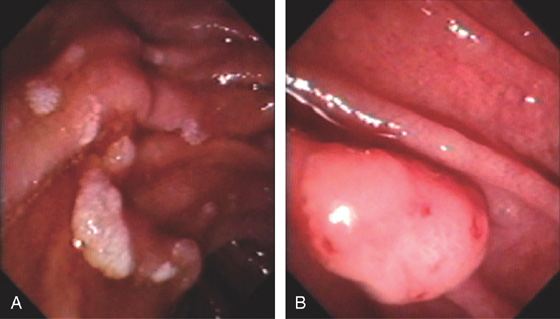

Figure 4.65 FAMILIAL ADENOMATOUS POLYPOSIS

A, Multiple sessile to slightly raised lesions with central discoloration in the second duodenum. B, Large mushroom-shaped polyp on the lateral wall of the second duodenum. Biopsy results demonstrated adenoma. The patient had previously undergone total colectomy for familial adenomatous polyposis coli syndrome.

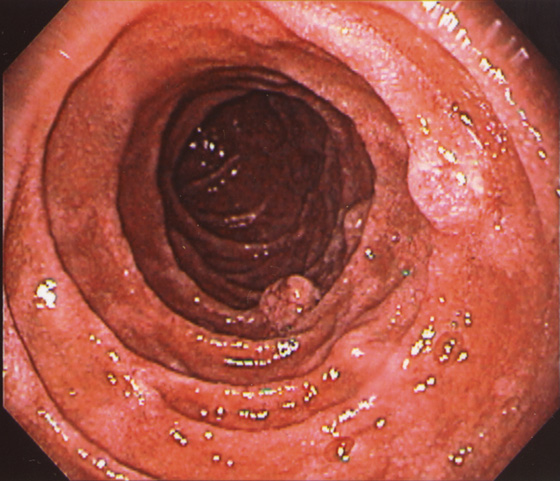

Figure 4.66 ADENOMA

Large adenomatous polyp at the superior duodenal angle posteriorly. The polypoid lesion is somewhat nodular and has a superficial texture suggestive of adenoma.

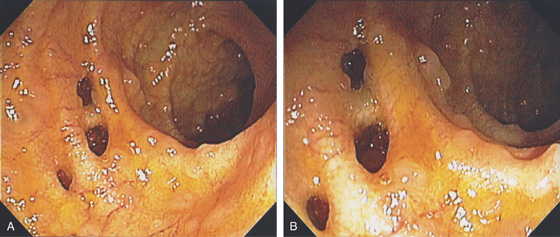

A, B, Sessile adenoma of the mid-second duodenum. Note the whitish texture, which is characteristic of adenomas in the duodenum. C, Large hemicircumferential lesion. D, Large lesion inferior to ampulla.

Figure 4.68 ADENOMA

A, Well-circumscribed adenoma at the junction of first and second duodenum. B, Appearance with narrow band imaging. C, Endoscopic resection of lesion.

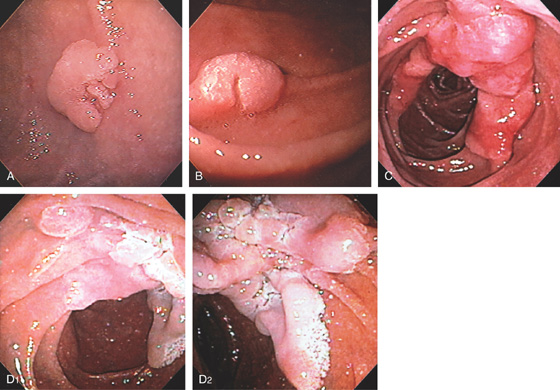

Figure 4.69 ADENOMA WITH ENDOSCOPIC MUCOSAL RESECTION

A, Sessile adenoma in the second duodenum. B, Adenoma with shiny appearance inferior to the ampulla. This is the appearance with the forward viewing endoscope. C, Dilute epinephrine is injected underneath the lesion.

D, Further submucosal injection raises the polyp. E, The snare is placed around the lesion. F, The snare is closed. G, Mucosal defect created after complete resection.

Figure 4.70 VILLOUS ADENOMA

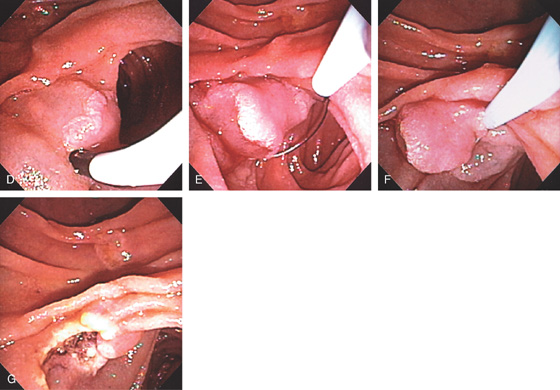

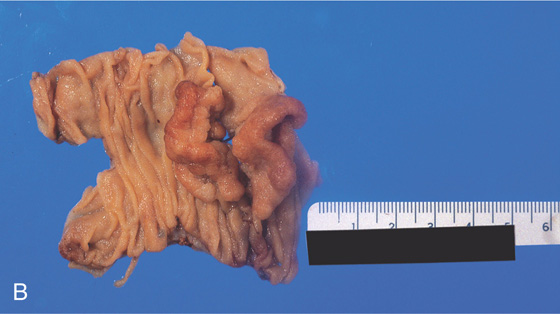

A, The lesion appears to emanate from the distal duodenum (A1, A2). The center of the lesion is covered with bile and has a frondlike appearance, suggestive of adenomatous tissue (A3). The lesion appears to be on the lateral duodenum when the instrument is advanced, documenting the center of the lesion (A4).

B, Surgical specimen has been partially everted, demonstrating the well-circumscribed nature of the lesion.

Figure 4.71 CARCINOID TUMORS ASSOCIATED WITH MULTIPLE ENDOCRINE NEOPLASIA TYPE 1 AND ZOLLINGER-ELLISON SYNDROME

Multiple round nodular lesions in the second duodenum.

Figure 4.72 GARDNER’S SYNDROME

Multiple polyps in the periampullary area (A) and mid-and second duodenum (B).

Figure 4.73 COWDEN’S SYNDROME

Large polypoid lesion in the second duodenum.

Figure 4.74 PEUTZ-JEGHERS POLYPS

Multiple small polyps in the second duodenum.

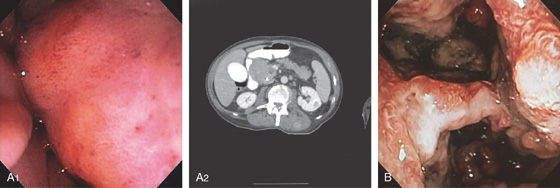

Figure 4.75 ADENOCARCINOMA

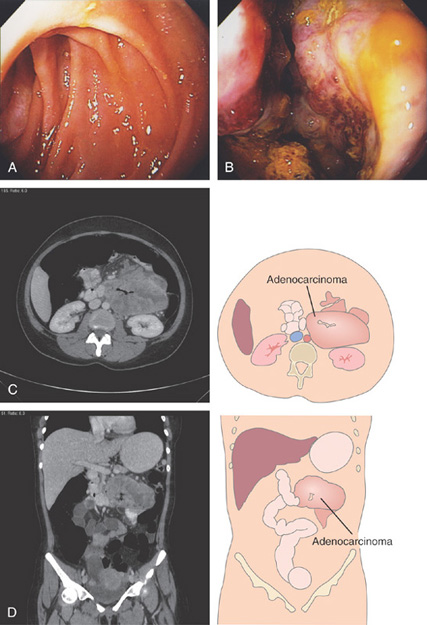

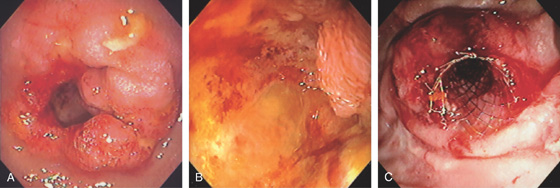

A, The duodenal sweep is dilated and markedly circumferentially thickened. The common bile duct is seen. This suggests a masslike lesion of the proximal second duodenum. B, Extrinsic compression in the distal duodenal bulb. The overlying mucosa appears normal. C, Hemicircumferential ulcerative lesion in the proximal second duodenum. The adenocarcinoma was believed to be of primary duodenal origin. Pancreatic carcinoma may present with duodenal abnormalities.

Figure 4.76 ADENOCARCINOMA

A, Narrowing of the junction of first and second duodenum with nodularity and a large central ulceration. B, There is circumferential ulceration with impending obstruction. C, Enteral stent was placed for palliation.

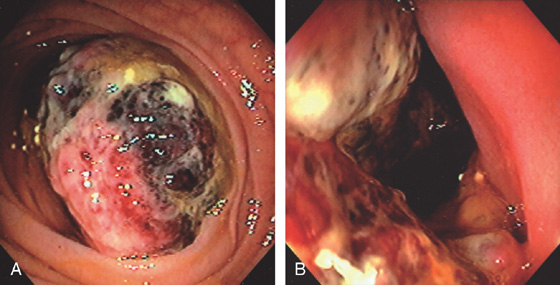

Figure 4.77 ADENOCARCINOMA

A, At the junction of the second and third duodenum, a glimpse of abnormal tissue is shown. B, A circumferential ulcerated mass lesion is identified with further advancement. C, D, CT images show the extensiveness of the mass.

Figure 4.78 KAPOSI’S SARCOMA

A, Hemorrhagic polypoid lesion in the mid-second duodenum. B, A large lesion was also present near the pylorus. C, Well-circumscribed, raised, dark polypoid lesion in the second duodenum.

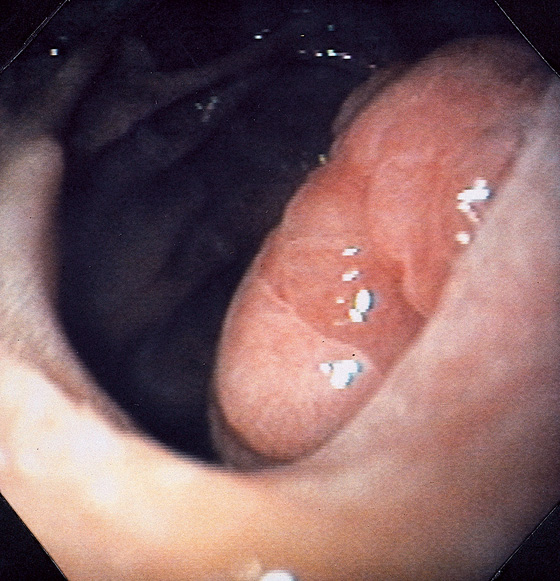

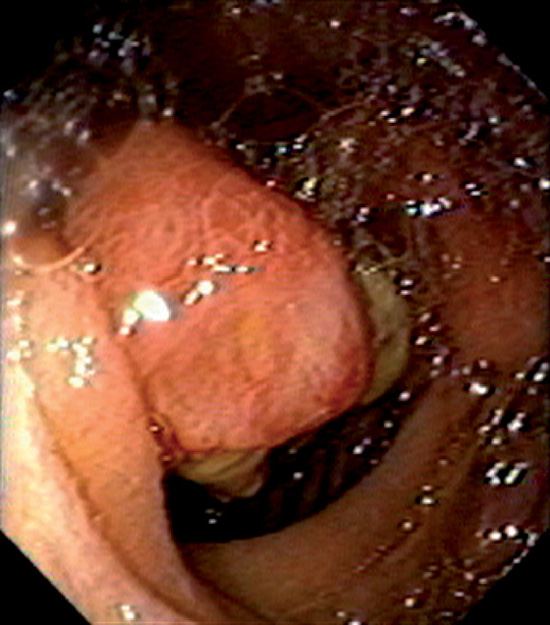

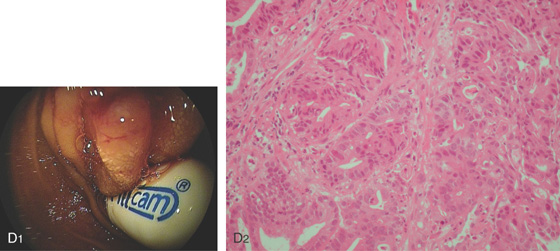

Figure 4.79 GASTROINTESTINAL STROMAL TUMOR

A, Large mass lesion occupying the lumen of the distal duodenum. B, Hemicircumferential nature of the tumor is apparent.

C, The appearance of the stent and tumor in the surgical specimen.

Figure 4.80 GASTROINTESTINAL STROMAL TUMOR

Large hemorrhagic mass lesion.

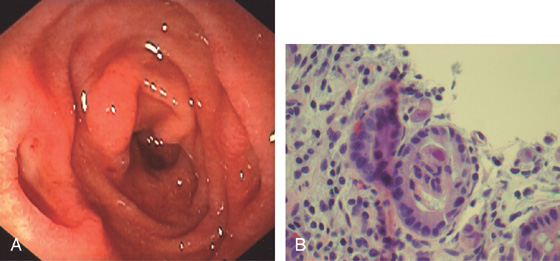

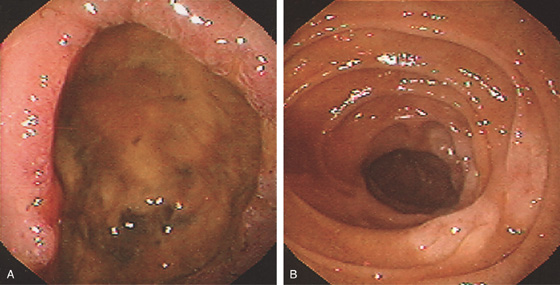

Figure 4.81 NON-HODGKIN’S LYMPHOMA

Nodularity of the duodenal bulb and filling defect in the proximal third duodenum.

Figure 4.82 NON-HODGKIN’S LYMPHOMA

A, Fleshy mass lesions in the second duodenum.

B, Malignant lymphoid cells distorting the duodenal glands.

Figure 4.83 NON-HODGKIN’S LYMPHOMA

A, Large anterior wall duodenal ulcer. B, White plaquelike lesions in the second duodenum.

![]() Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (Figure 4.83)

Giant benign duodenal ulcer

Adenocarcinoma

Extrinsic lesion

Neoplasm

Infection

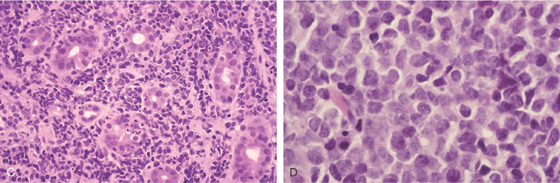

Figure 4.84 NON-HODGKIN’S LYMPHOMA

A, Smooth fold thickening throughout the second duodenum. B, The duodenum is markedly thickened.

C, D, Diffuse large cell lymphoma.

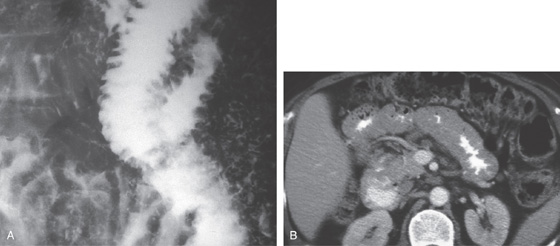

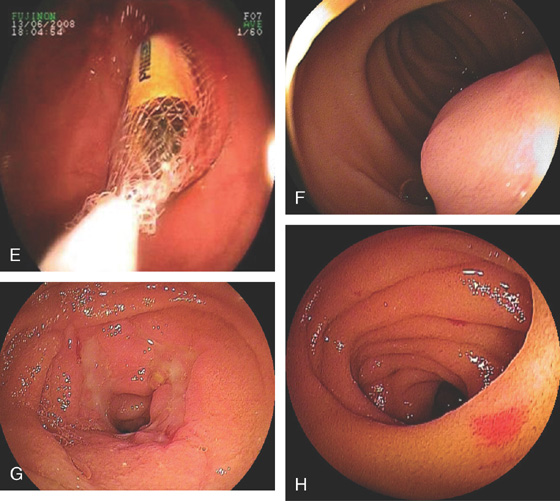

Figure 4.85 MANTLE CELL LYMPHOMA

A, Small-bowel series shows diffuse mucosal thickening. B, Marked duodenal and proximal jejunal thickening.

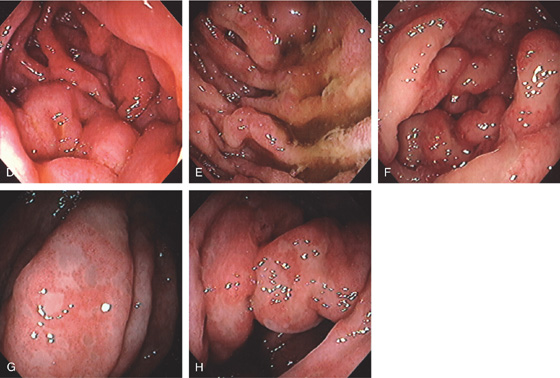

Figure 4.85 MANTLE CELL LYMPHOMA

C, Diffuse small-bowel thickening and thickening of the colon.

D, Fold thickening in the second duodenum, proximal jejunum (E), and ileum (F). There was also colonic involvement with loss of mucosal vascular pattern, patchy ulceration, and mucosal thickening (G, H).

Figure 4.86 MELANOMA

A1, Large, masslike lesion impinging on the second duodenum. A2, Large mass in the peripancreatic area. B, Large, ulcerated, masslike lesion in the second duodenum. No normal mucosa is present.

Figure 4.87 MELANOMA

A, Small dark lesion in the proximal second duodenum. B, Large darkly discolored lesion eroding into the second duodenum.

Figure 4.88 METASTATIC HYPERNEPHROMA

Submucosal mass with overlying erosions.

Figure 4.89 METASTATIC LUNG CANCER

Multiple lesions in the second duodenum. One lesion has a small ulceration (A), whereas the other lesion has a raised volcano appearance with a deep ulcer (B).

![]() Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Metastatic Lung Cancer (Figure 4.89)

Inflammatory polyp

Adenomatous polyp

Metastatic neoplasm

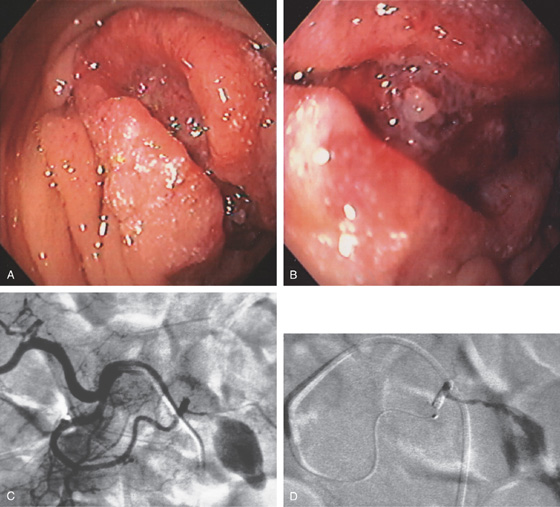

Figure 4.90 COLON CANCER INVOLVING DUODENUM

A, Well-circumscribed mass lesion in the second duodenum. B, A fleshy visible vessel was seen in the center of the lesion presumably at the site of recent bleeding. C, Angiography shows a large tumor blush. D, Post-embolization film demonstrates the placed coils and markedly reduced blood flow.

Figure 4.91 METASTATIC RECTAL CANCER

Submucosal lesion in the mid-second duodenum.

Figure 4.92 METASTATIC PSEUDOMYXOMA PERITONEI

Fleshy lesion in the mid-second duodenum.

Figure 4.93 CYTOMEGALOVIRUS ULCERATION

Marked edema and subepithelial hemorrhage in the duodenal bulb. A well-circumscribed, clean-based ulcer is present, with an ulcer also present in the distance.

Figure 4.94 CYTOMEGALOVIRUS ULCER

A, Well-circumscribed ulcer with a punched-out appearance in the mid-second duodenum. Red spots are present in the ulcer base. This patient was status post–renal transplantation and had no clinical bleeding. B, Characteristic viral cytopathic effect in the epithelial cells.

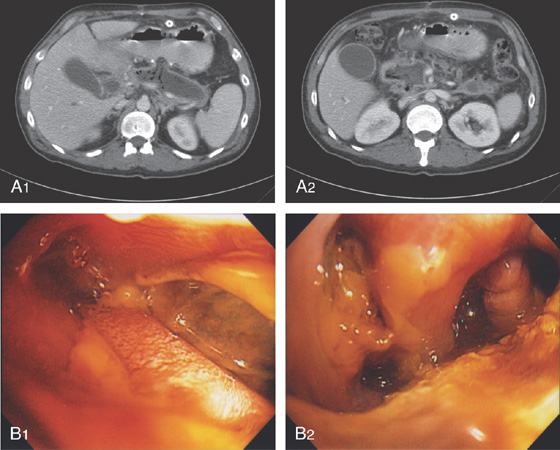

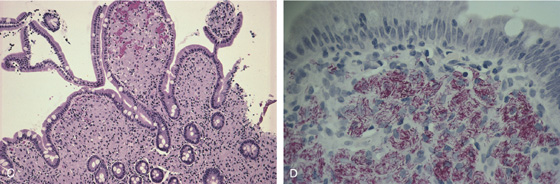

Figure 4.95 MYCOBACTERIUM AVIUM COMPLEX

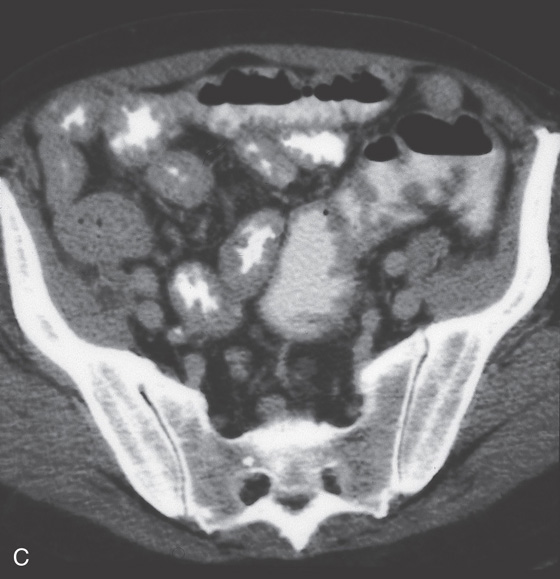

A, There appears to be thickening of the wall of the third and fourth duodenum and proximal jejunum. There is marked adenopathy of the retroperitoneum and small-bowel mesentery. The lumen of the third duodenum and proximal jejunum appears narrowed and nodular, with associated bowel wall thickening. B, Multiple nodular lesions throughout the second duodenum. The circular folds appear somewhat thickened. The surrounding mucosa does not have an ulcerated or inflamed appearance.

C, The duodenal villi are bulbous and markedly distorted. There is a monotonous infiltrate of benign granular macrophages in the lamina propria. D, Fite stain of the duodenum demonstrates macrophages stuffed with slender acid-fast bacilli.

E, Autopsy specimen demonstrates the marked thickening of the duodenum from infection with Mycobacterium avium complex.

Figure 4.96 CRYPTOSPORIDIOSIS

A, Marked thickening of the duodenal folds. B, The mucosa has a very granular, whitish appearance, and the circular folds are thickened. Marked inflammation was present on biopsy.

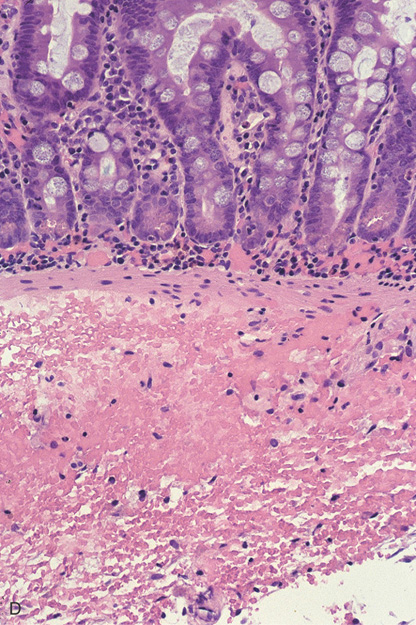

Figure 4.97 CRYPTOSPORIDIOSIS

A1, Diffuse erythema and granularity with some loss of the duodenal folds (A2). B, Histology shows mild blunting of the villi with a marked inflammatory process. C, Numerous small, round structures are seen on the surface epithelium representing the cryptosporidial organisms.

Figure 4.98 GIARDIASIS

A, Marked nodularity and loss of the normal mucosal pattern. B, Marked inflammation associated with numerous Giardia organisms represented by the crescent-like structures at the epithelial surface.

Figure 4.99 ASCARIS LUMBRICOIDES

Large worm filling the duodenum. (Courtesy F. Vida, MD, and A. Tomas, MD, Manresa, Spain.)

Figure 4.100 WHIPPLE’S DISEASE

A1, Multiple yellow nodular lesions in the second duodenum. A2, Close-up shows engorgement of the villi. B, Multiple diffuse white plaques.

C, Erythema with thickened folds. D, Hematoxylin and eosin staining shows effacement of the normal duodenal architecture.

E, Periodic acid-Schiff stain shows multiple positively staining cells representing the bacteria in macrophages.

Figure 4.101 DUODENAL SARCOIDOSIS

A, Thickened folds of the duodenal bulb and second duodenum. B, Marked fold thickening with scattered erosions.

C, Large, noncaseating granuloma.

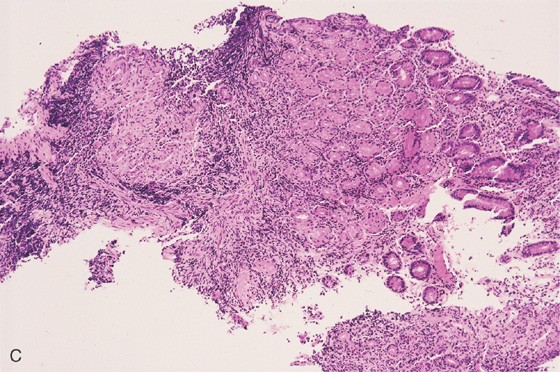

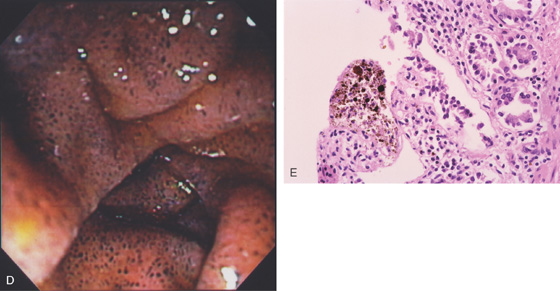

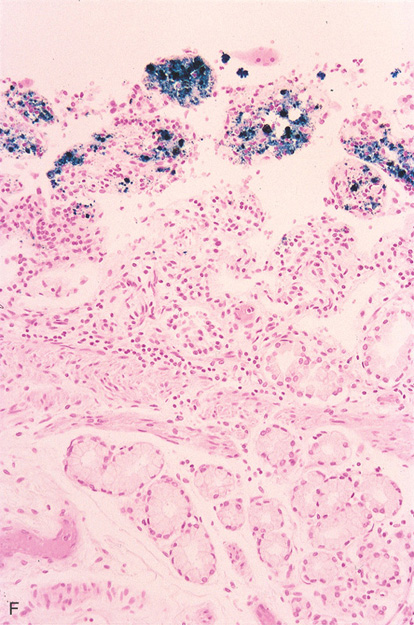

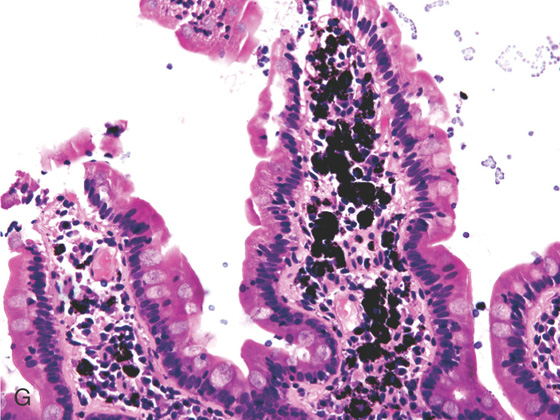

Figure 4.102 PSEUDOMELANOSIS DUODENI

A, Black speckling of the second duodenum. B, More significant pigmentation. C, Striking black discoloration of the mucosa.

D, More extensive involvement. E, Black pigment apparent in the mucosa on low-power view.

Figure 4.102 PSEUDOMELANOSIS DUODENI

F, Iron stain highlights the pigment.

G, Black pigment seen in the duodenal submucosa on high-power image.

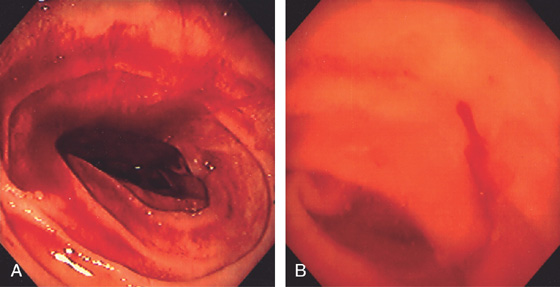

Figure 4.103 LYMPHANGIECTASIA

Duodenal lymphangiectasia as shown on routine (A) and narrow band imaging (B).

C, D, Lymphatic channels readily apparent at the mucosal surface.

Figure 4.104 LIPID PLAQUE

Well-circumscribed yellow plaque with a white speckled surface. Biopsy results demonstrated a focal lipid collection. These lipid collections can be seen throughout the gastrointestinal tract.

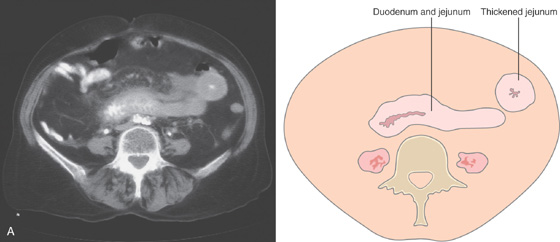

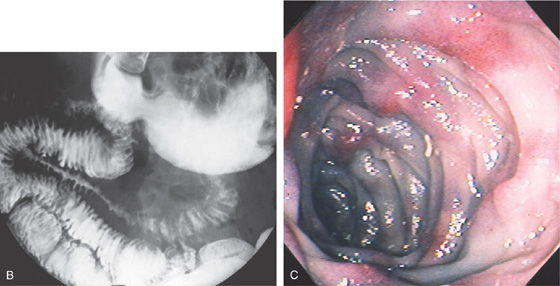

Figure 4.105 INTRAMURAL HEMORRHAGE

A, Marked edema of the second duodenum and proximal jejunum. The jejunum has a markedly thickened wall, with small collections of barium in the center representing the lumen.

B, Marked spiculation and nodularity of the duodenum, with luminal narrowing in the second duodenum. There is separation between the duodenal loops in this area, resulting from wall thickening. C, Marked thickening and subepithelial hemorrhage throughout the distal second duodenum. In some areas where there is no subepithelial hemorrhage, the mucosa has a bluish hue.

Figure 4.105 INTRAMURAL HEMORRHAGE

D, There is focal hemorrhage in the lamina propria, and blood diffusely infiltrates the fibroconnective tissue of the submucosa. Bleeding in the lamina propria appears endoscopically as bright red subepithelial hemorrhage. The bluish discoloration represents the deeper, submucosal areas of hemorrhage.

Figure 4.106 AORTOENTERIC FISTULA

A, Large defect in the mid-second duodenum with central depression and overlying blood clot. B, With washing, a large defect is now visible.

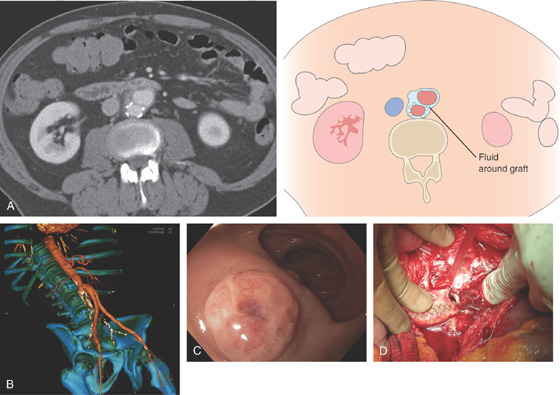

Figure 4.107 AORTOENTERIC FISTULA

A, Computed tomography (CT) shows fluid around the graft (right). B, CT with vascular image reconstruction shows the abnormality of the right iliac artery. C, Round, raised polypoid lesion in the duodenum. D, As seen at the time of surgery, the fistulous opening is obvious.

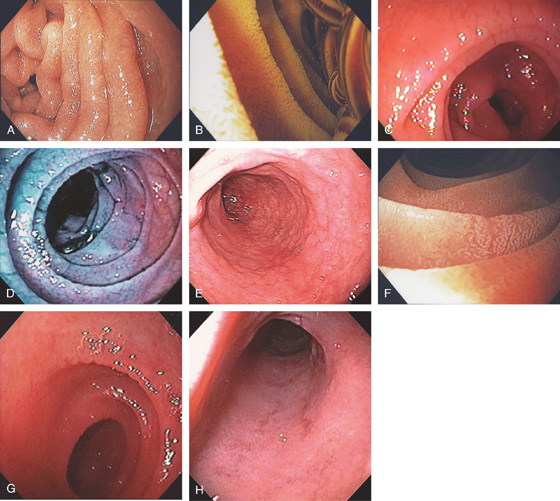

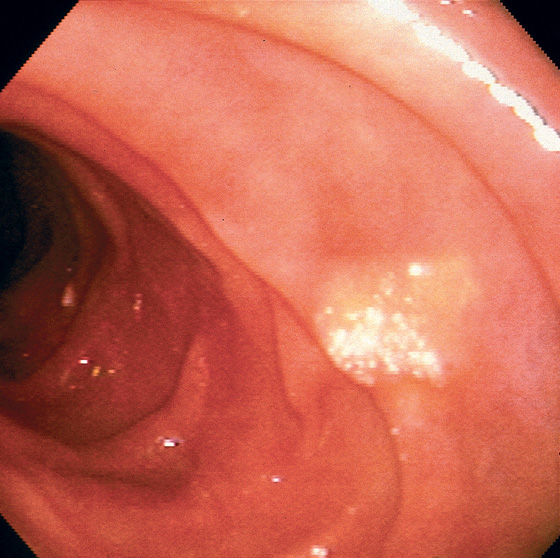

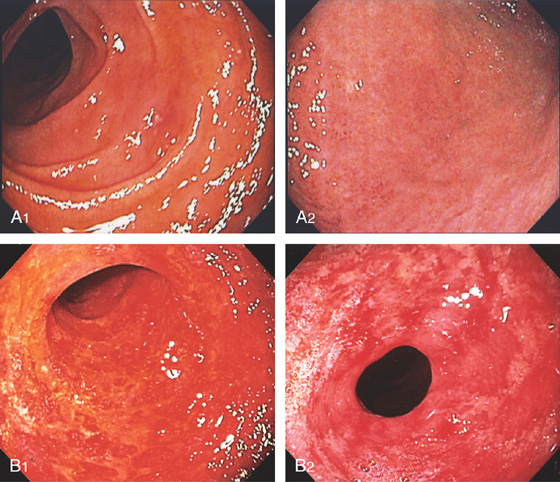

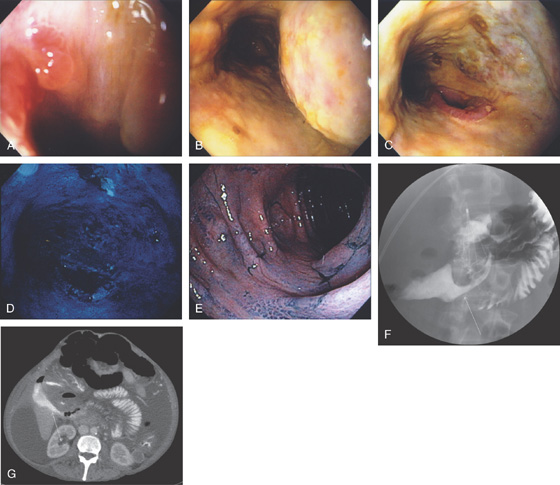

Figure 4.108 CELIAC SPRUE

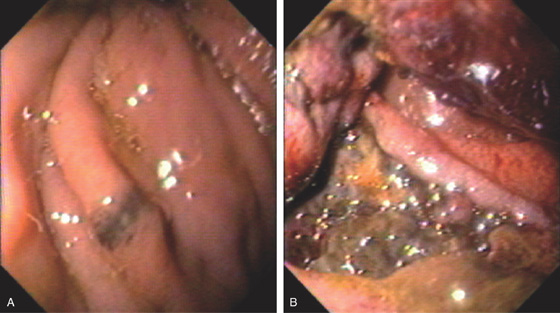

A, The duodenal folds appear slightly thickened. B, When viewed underwater, minimal villi are appreciated. C, Fissuring and mild nodularity of the valvulae conniventes. D, The mucosal changes are highlighted with methylene blue. E, Nodularity of the mucosa with absent folds. F, Subtle loss of the villi with some areas of epithelial loss. G, Smooth mucosa with some ridging to the folds. H, Completely flat smooth mucosa.

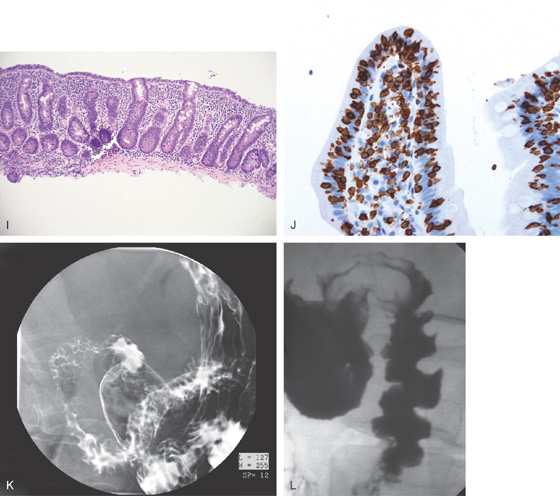

Figure 4.108 CELIAC SPRUE

I, Villous atrophy with chronic inflammation in the lamina propria. J, Numerous CD3 positively staining cells in the submucosa. K, Marked nodularity of the duodenum can be seen on barium study. L, Dilated duodenum with thickened folds.

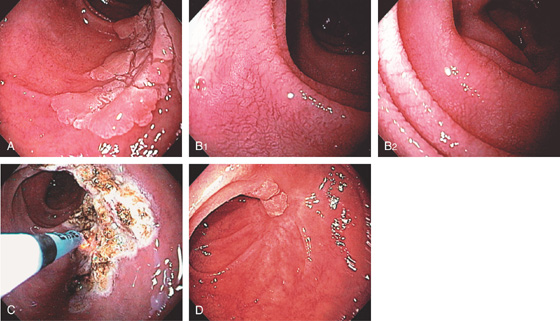

Figure 4.109 CELIAC SPRUE WITH ADENOMA

A, Large adenoma of the duodenum with its characteristic whitish mucosa. Note the flat surrounding mucosa. B1, B2, More proximally mucosal ridging and fissuring were evident. C, The lesion was ablated with argon plasma coagulation. D, Follow-up shows a small amount of residual tissue with scar.

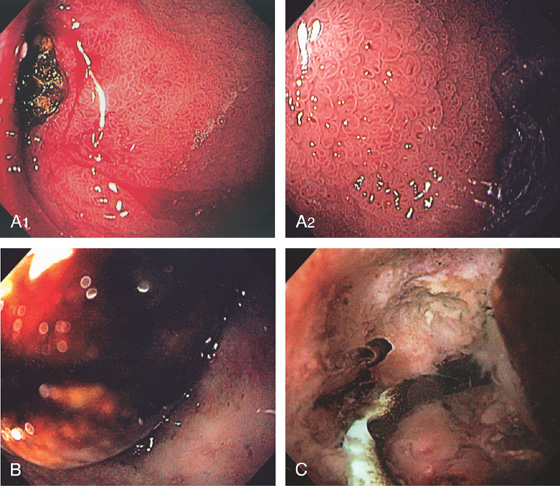

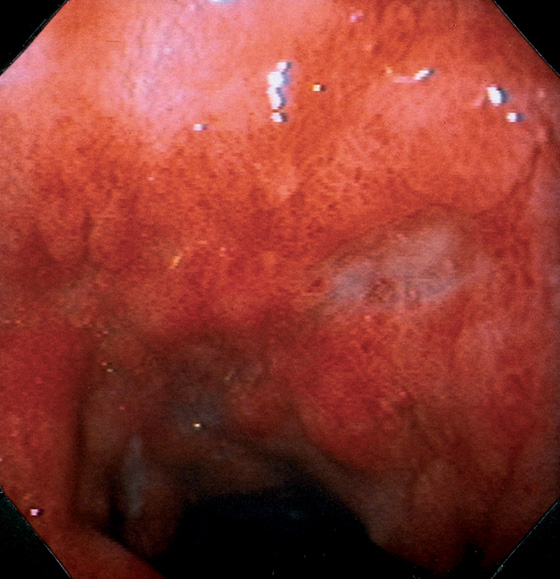

Figure 4.110 GRAFT-VERSUS-HOST DISEASE

A1, Patchy erythema of the second duodenum. A2, Mild changes were also present in the gastric antrum. B1, Diffuse hemorrhage and complete mucosal loss. Similar changes were present in the stomach (B2).

Figure 4.111 PANCREATITIS

A, Narrowing of the second duodenum. B, The wall of the second duodenum is markedly thickened. C, At the superior duodenal angle, the lumen is collapsed by edematous mucosa. There is no overlying mass lesion or ulceration (C1). The lumen is significantly narrowed at the superior duodenal angle (C2). In the second duodenum, bile is present; the masslike lesion can be seen anteriorly (C3). In the mid-second duodenum, the masslike lesion can be seen on the medial superior wall (C4).

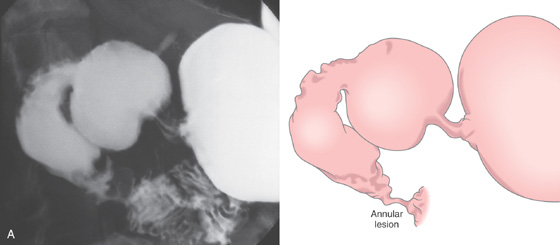

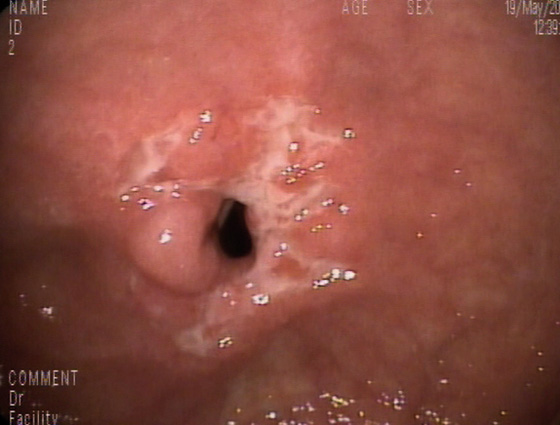

Figure 4.112 CHRONIC PANCREATITIS AND DUODENAL OBSTRUCTION

A, Irregular constricting lesion of the distal second duodenum compatible with a neoplasm. Barium is refluxing into the common bile duct.

B, A circumferential ulcerated area at the junction of the first and second duodenum, suggestive of carcinoma. Surgical exploration revealed only chronic pancreatitis.

![]() Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Chronic Pancreatitis and Duodenal Obstruction (Figure 4.112)

Primary duodenal adenocarcinoma

Pancreatic carcinoma

Other extrinsic inflammatory or neoplastic process

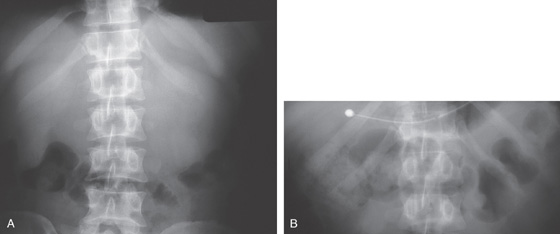

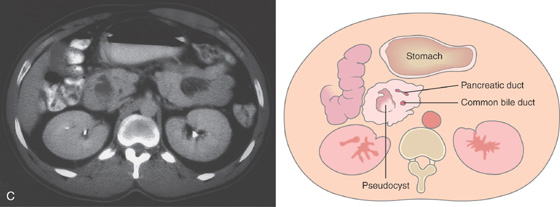

Figure 4.113 PANCREATIC PSEUDOCYST CAUSING DUODENAL OBSTRUCTION

A, Markedly dilated stomach displacing the transverse colon. B, After nasogastric suction, the transverse colon returns to its normal position.

C, The stomach is dilated, with no contrast material seen in the second duodenum. The pancreatic head is enlarged, and a pseudocyst is present.

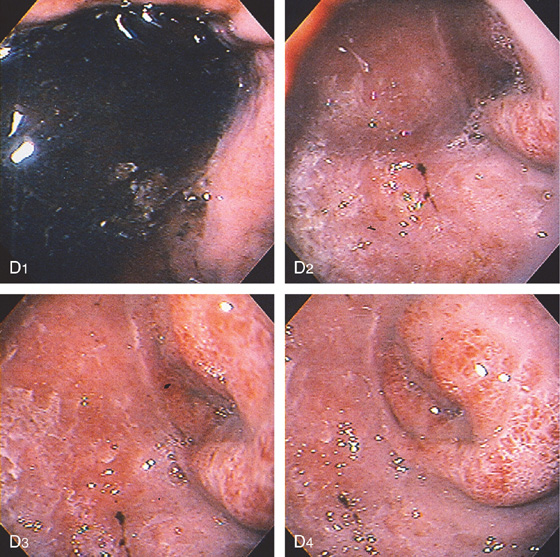

Figure 4.113 PANCREATIC PSEUDOCYST CAUSING DUODENAL OBSTRUCTION

D, The stomach is filled with fluid (D1); the duodenal bulb is inflamed, and a circumferential narrowing is present at the junction of the first and second duodenum (D2-D4).

E, The endoscope is advanced through the area of narrowing (E1-E3), which represents edema finally entering the second duodenum (E4).

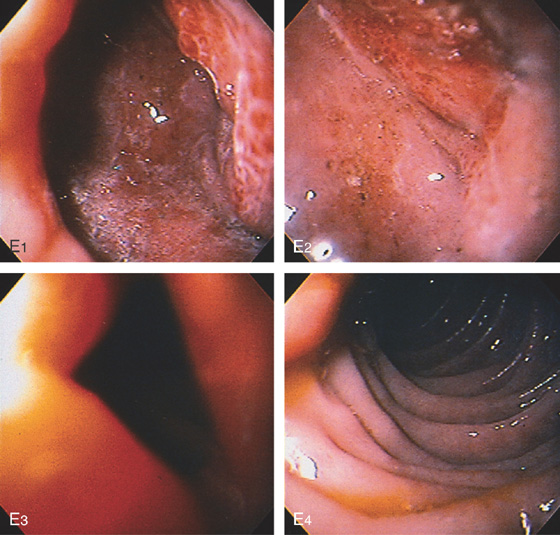

Figure 4.114 SPONTANEOUS PANCREATICODUODENAL FISTULA CAUSED BY NECROTIZING PANCREATITIS

A1, A2, CT shows complete pancreatic necrosis with air in the pancreatic bed. B1, Ulceration and distortion in the proximal second duodenum. B2, On entering the necrotic area, an opening is seen into the cavity of pancreatic necrosis.

Figure 4.115 SPONTANEOUS DUODENAL–COLONIC FISTULA FROM NECROTIZING PANCREATITIS

A, An opening in the second duodenum is identified. B, On entering the area a tubular circumferential ulcerated area is shown. C, An apparent opening to another structure. D, Methylene blue was placed into the cavity. E, Colonoscopy was performed demonstrating the methylene blue, although the fistula is not identified. F, UGI series shows the fistulous tract with communication to the colon (arrow). G, CT demonstrates an irregular extraluminal collection in the right upper quadrant (arrow).

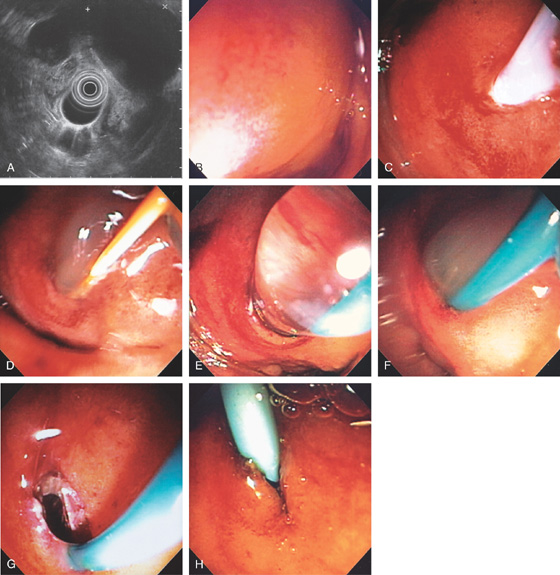

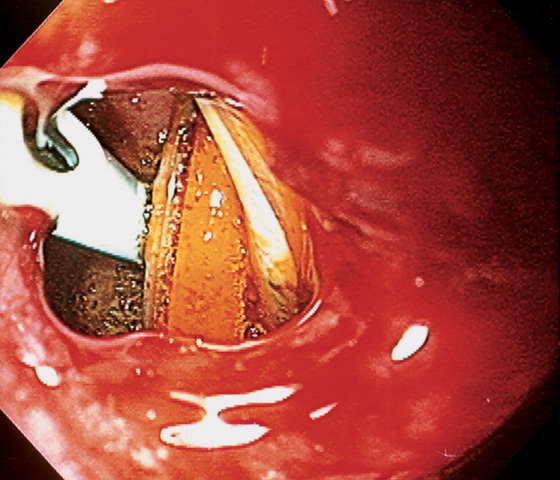

Figure 4.116 ENDOSCOPIC CYST DUODENOSTOMY

A, The cyst is large and free of internal echoes. No overlying vascular strictures are present. B, Large bulge is visible in the proximal duodenum. C, A needle is placed into the lesion. D, A guidewire exchange is performed with a large amount of cloudy material passing spontaneously through the puncture site. E, A balloon is inflated across the duodenal wall. F, G, Once deflated, a large defect is created and fluid again rapidly drains. H, A large double pigtail stent is placed into the cyst.

Figure 4.117 SPONTANEOUS FISTULA FROM PSEUDOCYST IN SECOND DUODENUM

A, Subtle mucosal defect in the second duodenum with overlying debris and subepithelial hemorrhage. B, The area was probed and a fistula to the cyst cavity identified. C, The fistulous tract is dilated.

Figure 4.118 DUODENAL DIVERTICULUM

A, Large diverticulum on the medial wall of the mid-second duodenum. Diverticula in the second duodenum are most commonly seen around the papilla. B, Multiple diverticula on the lateral wall of the second duodenum. C, Large diverticulum on the medial wall of second duodenum. This is likely the location of the major papilla.

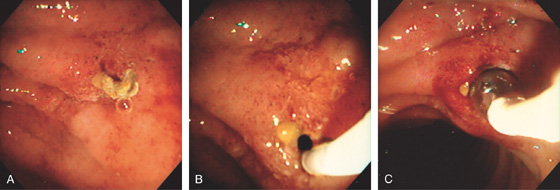

Figure 4.119 CHOLEDOCHODUODENOSTOMY

A, An opening can be seen in the anterior duodenal bulb, representing anastomosis of the distal common bile duct to the duodenum. Another small defect represents past erosion of a common bile duct stone into the duodenal wall. Anterior–posterior relationships in the duodenal bulb are important when defining ulcerative disease in the setting of gastrointestinal hemorrhage. The duodenum may be involved secondarily in the setting of disease of surrounding structures, most notably pancreatic disease with pancreatitis. B, Small defect anteriorly at the junction of first and second duodenum. A small gallstone is resting over the opening. C1, Opening in the proximal second duodenum represents the choledochoduodenal anastomosis. C2, On entering the anastomosis, the biliary tree and ducts are identified. C3, The common bile duct can be entered visualizing the hilum with junction of right and left common hepatic ducts. Note the presence of a soft gallstone in the distal left common hepatic duct. D1, Circumferential folds in the proximal duodenum. D2, The folds were gently entered, revealing an opening. D3, The endoscope was passed into the biliary system with radicals identified.

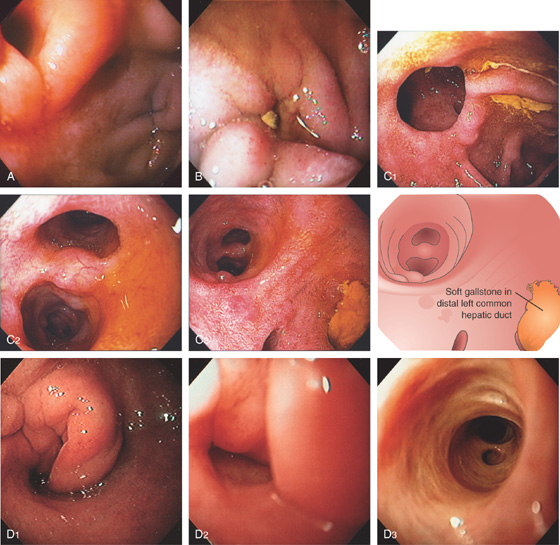

Figure 4.120 CHOLECYSTODUODENAL FISTULA

A1, Dark ulcer in the duodenal bulb with diffuse bulbar erythema. A2, Note the striking edema with accentuation of the duodenal mucosal pattern. B, Large gallstone at the entrance to the defect. C, Once you enter the defect, the gallbladder can be seen with a pigtail cholecystostomy tube.

Figure 4.121 PYLORUS-PRESERVING WHIPPLE

A, With the endoscope in the pylorus, two limbs are identified. B, The superior limb is entered and bile duct stents are found.

Figure 4.122 POSTSURGICAL DUODENAL PERFORATION

Large opening in the anterior wall of the duodenal bulb. A biliary tube is exiting the large defect. Other drains are in the opening. This patient recently had complicated biliary tract surgery.

Figure 4.123 POSTSURGICAL DEFECT

Large defect in the duodenal wall with the presence of gauze. This patient recently had complicated abdominal surgery with packing of infected tissue.

Figure 4.124 DIRECT PERCUTANEOUS ENDOSCOPIC JEJUNOSTOMY

A, A suitable site is identified in the jejunum by finger compression. B, A needle is placed into the jejunal lumen and then grasped with a snare (C).

D, After removal of the needle, a wire is advanced and grasped with the snare. Then the percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube is placed over the wire, with the PEG bumper now secure in the jejunal wall (E).

Figure 4.125 BLEEDING ULCER AT ROUX-EN-Y ANASTOMOSIS

A, Roux-en-Y anastomosis with fresh adherent blood clot. B, Ulceration at the anastomosis with clot.

Figure 4.126 CHOLEDOCHOJEJUNOSTOMY

Ulceration at the site of a choledochojejunostomy in a patient recently status post-liver transplantation.

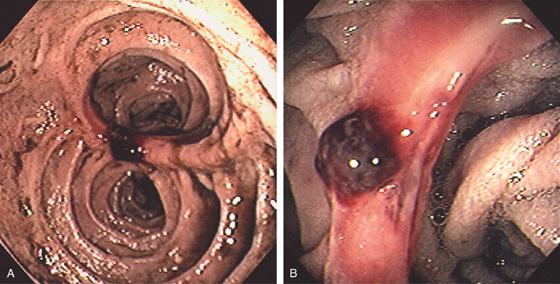

Figure 4.127 ENTERAL STENT PLACEMENT FOR MALIGNANT OBSTRUCTION

A1, Duodenal narrowing caused by tumor and prior radiation therapy. A2, The duodenum is markedly dilated. A biliary tube is present. B1, Under fluoroscopic guidance, a catheter is passed through the lesion and injection confirms adequate position in the duodenum. B2, The patient has a percutaneous biliary pigtail catheter in distal duodenum. C, A guidewire is passed to the distal duodenum. D1, D2, The metallic prosthesis is advanced over the wire. E1, E2, The stent has been deployed.

Figure 4.127 ENTERAL STENT PLACEMENT FOR MALIGNANT OBSTRUCTION

F, Barium study shows flow through the prosthesis.

Figure 4.128 JEJUNAL DIVERTICULA

Multiple diverticula in the proximal jejunum.

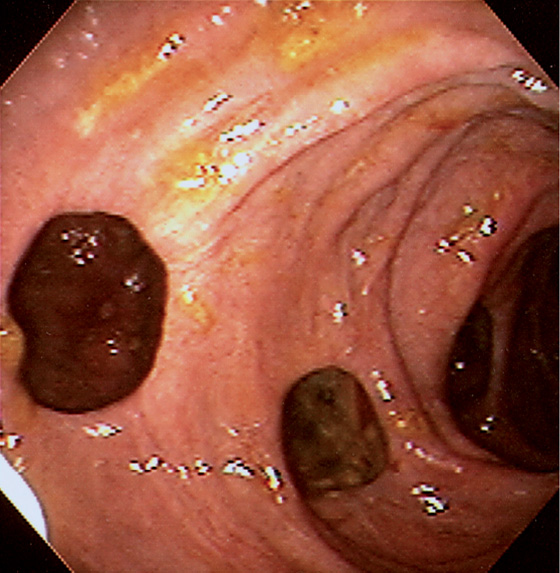

Figure 4.129 MULTIPLE ILEAL DIVERTICULA

A, Multiple diverticula in the distal ileum identified at colonoscopy. Note the presence of lymphoid follicles (B).

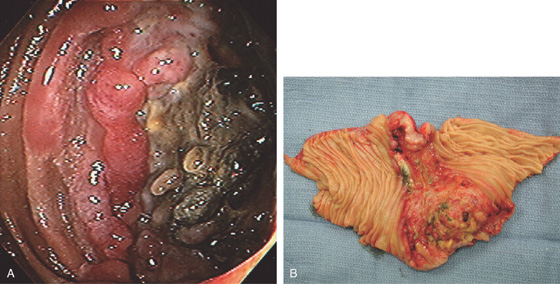

Figure 4.130 JEJUNAL GASTROINTESTINAL STROMAL TUMOR

Submucosal tumor with central ulceration.

Figure 4.131 JEJUNAL GASTROINTESTINAL STROMAL TUMOR

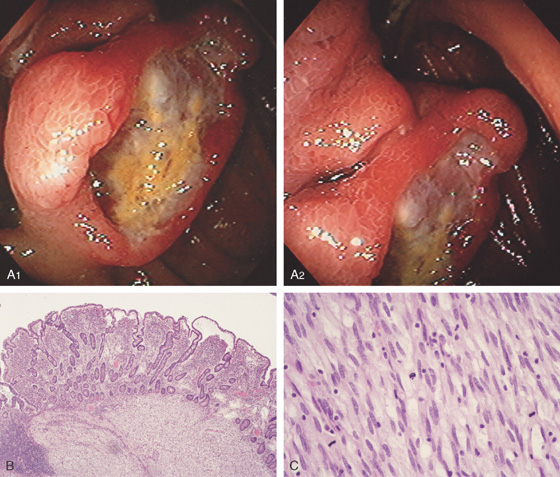

A1, A2, Ulcerated lesion in the proximal jejunum with surrounding thickened folds. B, Low-power view shows effacement of the mucosa with infiltrating tumor. C, High-power view shows numerous mitoses, one feature of malignancy in gastrointestinal stromal tumors.

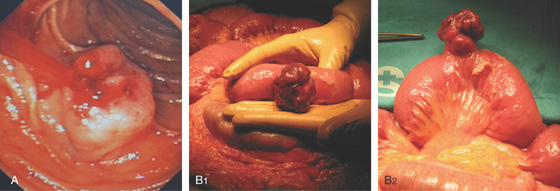

Jejunal Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor (Figure 4.131)

Metastatic lesion

Primary small intestinal adenocarcinoma

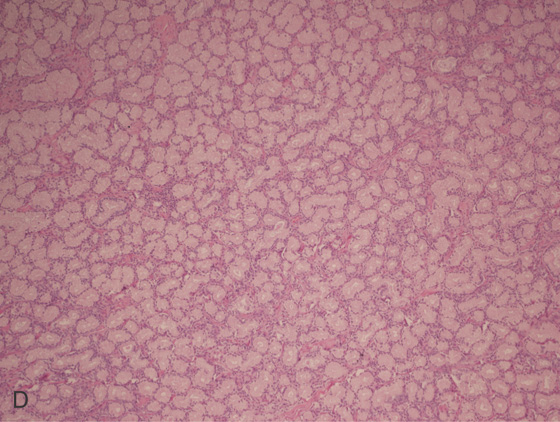

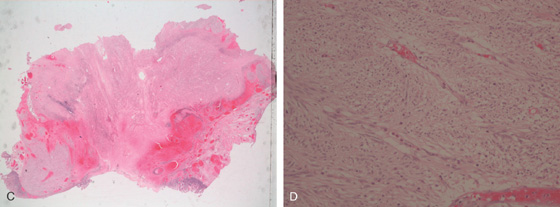

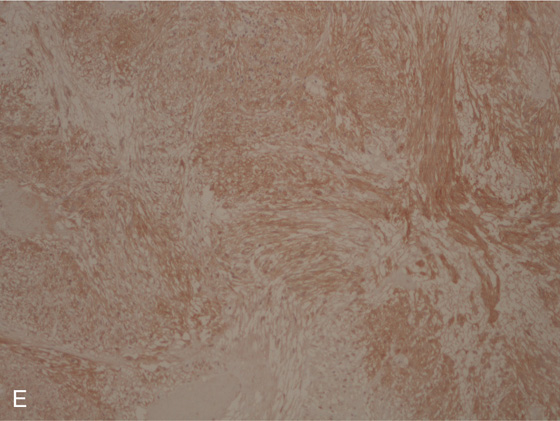

Figure 4.132 JEJUNAL GASTROINTESTINAL STROMAL TUMOR

Mass lesion with central ulceration in the proximal jejunum.

Figure 4.133 JEJUNAL GASTROINTESTINAL STROMAL TUMOR

A, Submucosal mass lesion with fresh bleeding. B1, B2, View at the time of surgery demonstrates the extraluminal component.

Figure 4.133 JEJUNAL GASTROINTESTINAL STROMAL TUMOR

C, D, Bland stroma typical for a gastrointestinal stromal tumor.

E, The tumor stains positively for c-kit receptor.

Figure 4.134 JEJUNAL LYMPHOMA

A, Ulcerated lesion with central necrosis. B, Circumferential nature of the lesion is apparent.

Figure 4.135 JEJUNAL METASTATIC LESIONS

A, Jejunal metastasis. Squamous cell metastasis from a head and neck cancer. B, Metastatic melanoma. Fleshy mass lesion in the jejunum. C, Metastatic lung cancer. Necrotic circumferential mass lesion.

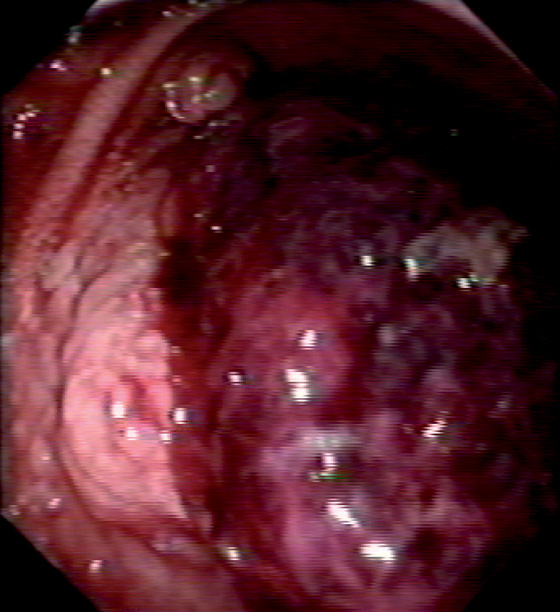

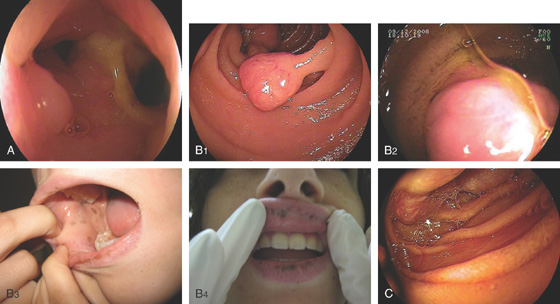

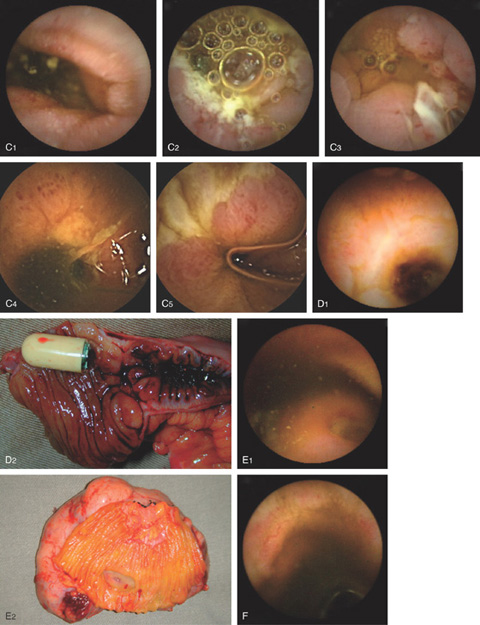

Figure 4.136 CAPSULE ENDOSCOPY

A, Large ectasia. B, Polypoid small-bowel neoplasm.

Figure 4.136 CAPSULE ENDOSCOPY

C, Crohn’s disease. D, Crohn’s disease with stricture. There is a stricture in the small bowel ultimately requiring surgery where the capsule was retained. E, Gastrointestinal stromal tumor. F, Radiation-induced ectasia.

Figure 4.136 CAPSULE ENDOSCOPY

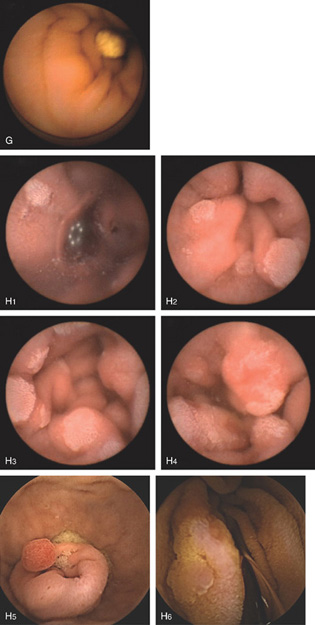

G, Lymphangiectasia. H, Familial adenomatous polyposis. Numerous adenomas are apparent in the small bowel. H5, Tubular adenoma in duodenum. H6, Tubular adenoma.

Figure 4.136 CAPSULE ENDOSCOPY

I, Ancylostoma worm in jejunum. J, Ampulla of Vater. K, Celiac disease. L, Duodenal ulcer. M, Duodenal Brunner’s gland hamartoma. N, Peutz-Jeghers polyp with intussusception. O, Tapeworm. P, Portal hypertensive gastropathy. Q, Endoscopic clip at the site of prior vascular ectasia. (I courtesy O. Alarcón, MD, Tenerife, Spain.)

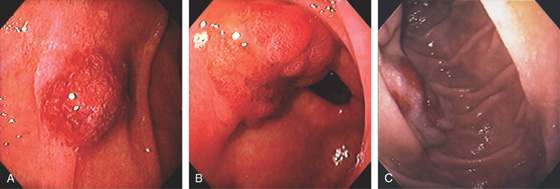

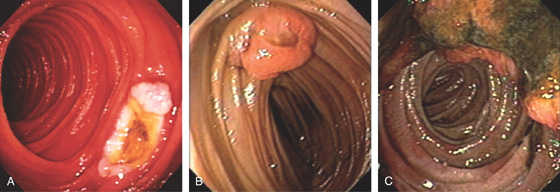

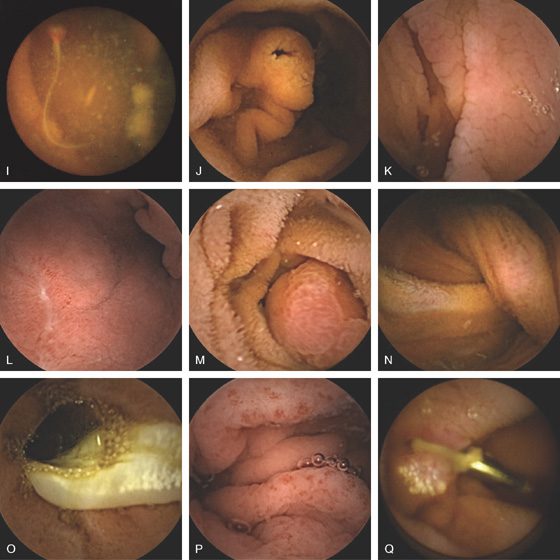

Figure 4.137 DOUBLE BALLOON ENTEROSCOPY

A, Fistula. B1, B2, Jejunal polyp histologically confirmed to be a hamartoma in the setting of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. B3, Typical oropharyngeal lesions. C, Adenocarcinoma.

Figure 4.137 DOUBLE BALLOON ENTEROSCOPY

D1, Retained capsule above a stricture. D2, The obstruction is caused by an adenocarcinoma.

E, Removal of retained capsule. F, Gastrointestinal stromal tumor. G, Circumferential ulceration from Crohn’s disease. H, Solitary vascular ectasia. (A courtesy E. Pérez-Cuadrado, MD.)