Chapter 17 Drugs and the skin

This account is confined to therapy directed primarily at the skin and covers the following topics:

Dermal pharmacokinetics

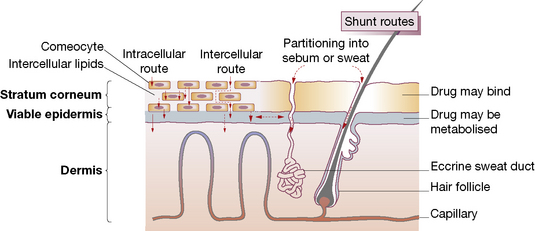

Human skin is a highly efficient self-repairing barrier that permits terrestrial life by regulating heat and water loss while preventing the ingress of noxious chemicals and microorganisms. A drug applied to the skin may diffuse from the stratum corneum into the epidermis and then into the dermis, to enter the capillary microcirculation and thus the systemic circulation (Fig. 17.1). The features of components of the skin in relation to drug therapy, whether for local or systemic effect, are worthy of examination.

• Physicochemical features: lipophilic drugs can utilise the intracellular route because they readily cross cell walls, whereas hydrophilic drugs principally take the intercellular route, diffusing in fluid-filled spaces between cells.

• Molecular size: most therapeutic agents suitable for topical delivery measure 100–500 Da.

Drugs are presented in vehicles (bases1), designed to vary in the extent to which they increase hydration of the stratum corneum; e.g. oil-in-water creams promote hydration (see below). Increasing the water content of the stratum corneum via occlusion or hydration generally increases the penetration of both lipophilic and hydrophilic materials. This may be due to an increased fluid content of the lipid bilayers. The stratum corneum and stratum granulosum layers become more similar with hydration and occlusion, thus lowering the partition coefficient of the molecule passing through the interface. Some vehicles also contain substances intended to enhance penetration by reducing the barrier properties of the stratum corneum, e.g. fatty acids, terpenes, surfactants. Encapsulation of drugs into vesicular liposomes may enhance drug delivery to specific compartments of the skin, e.g. hair follicles.

Transdermal delivery systems are now used to administer drugs via the skin for systemic effect; the advantages and disadvantages of this route are discussed on page 88.

Vehicles for presenting drugs to the skin

Solid preparations

Solid preparations such as dusting powders, e.g. zinc starch and talc,2 may cool by increasing the effective surface area of the skin and they reduce friction between skin surfaces by their lubricating action. Although usefully absorbent, they cause crusting if applied to exudative lesions. They may be used alone or as specialised vehicles for, e.g., fungicides.

Emollients and barrier preparations

Emollients

hydrate the skin, and soothe and smooth dry scaly conditions. They need to be applied frequently as their effects are short lived. There is a variety of preparations but aqueous cream, in addition to its use as a vehicle (above), is effective when used as a soap substitute. Various other ingredients may be added to emollients, e.g. menthol, camphor or phenol for its mild antipruritic effect, and zinc and titanium dioxide as astringents.3

Barrier preparations

Silicone sprays and occlusives, e.g. hydrocolloid dressings, may be effective in preventing and treating pressure sores. Masking creams (camouflaging preparations) for obscuring unpleasant blemishes from view are greatly valued by patients.4 They may consist of titanium oxide in an ointment base with colouring appropriate to the site and the patient.

Adrenocortical steroids

Actions

Adrenal steroids possess a range of actions, of which the following are relevant to topical use:

• Inflammation is suppressed, particularly when there is an allergic factor, and immune responses are reduced.

• Antimitotic activity suppresses proliferation of keratinocytes, fibroblasts and lymphocytes (useful in psoriasis, but also causes skin thinning).

• Vasoconstriction reduces ingress of inflammatory cells and humoral factors to the inflamed area; this action (blanching effect on human skin) has been used to measure the potency of individual topical corticosteroids (see below).

Uses

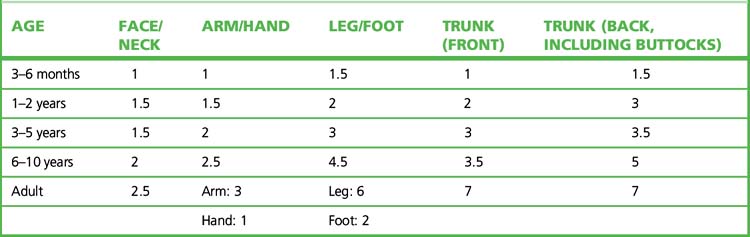

Topical corticosteroids should be applied sparingly. The ‘fingertip unit’5 is a useful guide in educating patients (Table 17.1). The difficulties and dangers of systemic adrenal steroid therapy are sufficient to restrict such use to serious conditions (such as pemphigus and generalised exfoliative dermatitis) not responsive to other forms of therapy.

Table 17.1 Fingertip unit dosimetry for topical corticosteroids (distance from the tip of the adult index finger to the first crease)

Guidelines for the use of topical corticosteroids

• Use for symptom relief and not prophylactically.

• Choose the appropriate therapeutic potency (Table 17.2), e.g. mild for the face. In cases likely to be resistant, use a very potent preparation, e.g. for 3 weeks, to gain control, after which change to a less potent preparation.

• Choose the appropriate vehicle, e.g. a water-based cream for weeping eczema, an ointment for dry, scaly conditions.

• Prescribe in small but adequate amounts so that serious overuse is unlikely to occur without the doctor knowing, e.g. weekly quantity by group (see Table 17.2): very potent 15 g; potent 30 g; other 50 g.

• Occlusive dressing should be used only briefly. Note that babies’ plastic pants are an occlusive dressing as well as being a social amenity.

• If it’s wet, dry it; if it’s dry, wet it. The traditional advice contains enough truth to be worth repeating.

• One or two applications a day are all that is usually necessary.

Table 17.2 Topical corticosteroid formulations conventionally ranked according to therapeutic potency

| Potency | Formulations |

|---|---|

| Very potent | Clobetasol (0.05%); also formulations of diflucortolone (0.3%), halcinonide |

| Potent | Beclometasone (0.025%); also formulations of betamethasone, budesonide, desoximetasone, diflucortolone (0.1%), fluclorolone, fluocinolone (0.025%), fluocinonide, fluticasone, hydrocortisone butyrate, mometasone (once daily), triamcinolone |

| Moderately potent | Clobetasone (0.05%); also formulations of alclometasone, clobetasone, desoximetasone, fluocinolone (0.00625%), fluocortolone, fluandrenolone |

| Mildly potent | Hydrocortisone (0.1–1.0%); also formulations of alclomethasone, fluocinolone (0.0025%), methylprednisolone |

Important note: the ranking is based on agent and its concentration; the same drug appears in more than one rank.

Choice

Topical corticosteroids are classified according to both drug and potency, i.e. therapeutic efficacy in relation to weight (see Table 17.2). Their potency is determined by the amount of vasoconstriction a topical corticosteroid produces (McKenzie skin-blanching test6) and the degree to which it inhibits inflammation. Choice of preparation relates both to the disease and the site of intended use. High-potency preparations are commonly needed for lichen planus and discoid lupus erythematosus; weaker preparations (hydrocortisone 0.5–2.5%) are usually adequate for eczema, for use on the face and in childhood.

Adverse effects

Used with restraint, topical corticosteroids are effective and safe. Adverse effects are more likely with formulations ranked therapeutically as very potent or potent in Table 17.2.

Other effects include:

Other complications of occlusive dressings include infections (bacterial, candidal) and even heat stroke when large areas are occluded. Antifungal cream containing hydrocortisone and used for vaginal candidiasis may contaminate the urine and misleadingly suggest Cushing’s syndrome.7

Applications to the eyelids may get into the eye and cause glaucoma.

Sunscreens (sunburn and photosensitivity)

Ultraviolet (UV) solar radiation

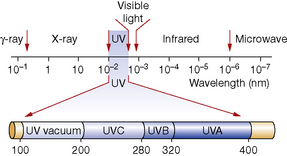

• UVA (320–400 nm), which damages collagen, contributes to skin cancer and drug photosensitivity.

• UVB (280–320 nm), which is 1000 times more active than UVA, acutely causes sunburn and chronically skin cancer and skin ageing.

• UVC (200–280 nm), which is prevented, at present, from reaching the earth at sea level by the stratospheric ozone layer, although it can cause skin injury at high altitude.

Protection of the skin

Drug photosensitivity

Systemically taken drugs that can induce photo-sensitivity are many, the most common being the following:8

• Antimitotics: dacarbazine, vinblastine, taxanes, methotrexate.

• Antimicrobials: demeclocycline, doxycycline, nalidixic acid, sulfonamides.

• Antipsychotics: chlorpromazine, prochlorperazine.

• Cardiac arrhythmic: amiodarone.

• Diuretics: furosemide, chlorothiazide, hydrochlorothiazide.

• Fibric acid derivatives, e.g. fenofibrate.

• Hypoglycaemics: tolbutamide.

• Antifungals: voriconazole (extreme photoxicity and heightened risk of SCC and melanoma).

Topically applied substances that can produce photosensitivity include:

• Para-aminobenzoic acid and its esters (used as sunscreens).

• Psoralens from juices of various plants, e.g. bergamot oil.

• 6-Methylcoumarin (used in perfumes, shaving lotions, sunscreens).

Cutaneous drug reactions

• Acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis.

• Stevens–Johnson syndrome/erythema multiforme/toxic epidermal necrolysis.

• Hypersensitivity reaction including DRESS (drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms), e.g. hepatitis. The pathogenesis of DRESS is likely to be multifactorial. The factors include deficient detoxification of a drug metabolite in patients who are genetically susceptible, drug interactions, and direct effects of drug-specific T cells. Recent reports of co-infection with human herpesvirus (HHV)-6 or HHV-7 and a transient hypogammaglobulinaemia may prove important in anticonvulsant hypersensitivity.

Some of the mechanisms involved in drug-induced cutaneous reactions are described in Box 17.1.

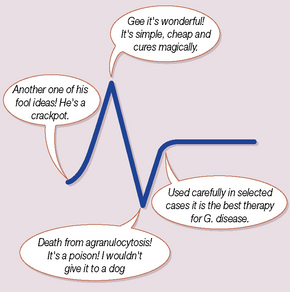

Although drugs may change, the clinical problems remain depressingly the same: a patient develops a rash; he or she is taking many different tablets; which, if any, of these caused the eruption, and what should be done about it? It is no answer simply to stop all drugs, although the fact that this can often be done casts some doubt on the patient’s need for them in the first place. All too often, potentially valuable drugs are excluded from further use on totally inadequate grounds. Clearly some guidelines are useful, but no simple set of rules exists that can cover this complex subject:9

1. Can other skin diseases be excluded and are the skin changes compatible with a drug cause? Clinical features that indicate a drug cause include the type of primary lesion (blisters, pustules), distribution of lesions (acral lesions in erythema multiforme), mucosal involvement and evidence of systemic involvement (fever, lymphadenopathy, visceral involvement).

2. Which drug is most likely to be responsible? Document all of the drugs the patient has been exposed to and the date of introduction of each drug. Determine the interval between commencement date and the date of the skin eruption. Chronology is important, with most reactions occurring about 10–12 days after starting a new drug or within 2–3 days in previously exposed patients. A search of standard literature sources of adverse reactions, including the pharmaceutical company data, can be helpful in identifying suspect drugs.

3. Are any further tests worthwhile? Excluding infectious causes of skin eruptions is important, e.g. viral exanthems, mycoplasma. A skin biopsy in cases of non-specific dermatitis is helpful, as a predominance of eosinophils would support a drug precipitant.

4. Is any treatment needed? Supporting the ill patient and stopping the causative drug is crucial.

Drug-specific rashes

• Acne and pustular: corticosteroids, androgens, ciclosporin, penicillins.

• Allergic vasculitis: sulfonamides, NSAIDs, thiazides, chlorpropamide, phenytoin, penicillin, retinoids.

• Anaphylaxis: X-ray contrast media, penicillins, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors.

• Bullous pemphigoid: furosemide (and other sulfonamide-related drugs), ACE inhibitors, penicillamine, penicillin, PUVA therapy.

• Eczema: penicillins, phenothiazines.

• Exanthematic/maculopapular reactions are the most frequent; unlike a viral exanthem, the eruption typically starts on the trunk; the face is relatively spared. Causes include antimicrobials, especially ampicillin, sulfonamides and derivatives (sulfonylureas, furosemide and thiazide diuretics).

• Morbilliform (measles-like) eruptions typically recur on rechallenge.

• Erythema multiforme: NSAIDs, sulfonamides, barbiturates, phenytoin, paclitaxel.

• Erythema nodosum: dermatitis and sulfonamides, oral contraceptives, prazosin.

• Exfoliative erythroderma: gold, phenytoin, carbamazepine, allopurinol, penicillins, neuroleptics, isoniazid.

• Fixed eruptions are eruptions that recur at the same site, often circumoral, with each administration of the drug: phenolphthalein (laxative self-medication), sulfonamides, quinine (in tonic water), tetracycline, barbiturates, naproxen, nifedipine.

• Hair loss: cytotoxic anticancer drugs, acitretin, oral contraceptives, heparin, androgenic steroids (women), sodium valproate, gold.

• Hypertrichosis: corticosteroids, ciclosporin, doxasosin, minoxidil.

• Lichenoid eruption: β-adrenoceptor blockers, chloroquine, thiazides, furosemide, captopril, gold, phenothiazines.

• Lupus erythematosus: hydralazine, isoniazid, procainamide, phenytoin, oral contraceptives, sulfazaline.

• Purpura: thiazides, sulfonamides, sulfonylureas, phenylbutazone, quinine. Aspirin induces a capillaritis (pigmented purpuric dermatitis).

• Photosensitivity: see above.

• Pemphigus: penicillamine, captopril, piroxicam, penicillin, rifampicin.

• Pruritus unassociated with rash: oral contraceptives, phenothiazines, rifampicin (cholestatic reaction).

• Pigmentation: oral contraceptives (chloasma in photosensitive distribution), phenothiazines, heavy metals, amiodarone, chloroquine (pigmentation of nails and palate, depigmentation of the hair), minocycline.

• Psoriasis may be aggravated by β-blockers, lithium and antimalarials.

• Scleroderma-like: bleomycin, sodium valproate, tryptophan contaminants (eosinophila–myalgia syndrome).

• Serum sickness: immunoglobulins and other immunomodulatory blood products.

• Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TENS): e.g. anticonvulsants, sulfonamides, aminopenicillins, NSAIDs, allopurinol, chlormezanone, corticosteroids.

• Urticaria and angioedema: penicillins, ACE inhibitors, gold, NSAIDs, e.g. aspirin, codeine.

Safety monitoring

• Aciclovir (plasma creatinine).

• Azathioprine (blood count and liver function).

• Colchicine (blood count, plasma creatinine).

• Ciclosporin (plasma creatinine).

• Dapsone (liver function, blood count including reticulocytes).

• Methotrexate (blood count, liver function).

The patient and doctor must always remain vigilant about drug–drug and drug–food interactions that may result in toxicity, e.g. methotrexate/trimethoprim, ciclosporin/grapefruit juice.

Individual disorders

Table 17.3 is not intended to give the complete treatment of even the commoner skin conditions but merely to indicate a reasonable approach. Secondary infections of ordinarily uninfected lesions may require added topical or systemic antimicrobials. Analgesics, sedatives or tranquilisers may be needed in painful or uncomfortable conditions, or where the disease is intensified by emotion or anxiety.

| Condition | Treatment | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Androgenic alopecia | Topical 2% or 5% minoxidil is worth trying. Finasteride can stop hair loss and increase hair density in 50% of men | The response occurs in 4–12 months; hair loss resumes when therapy is stopped |

| Alopecia areata | Potent topical or intralesional corticosteroids may be useful in the short term | Although distressing, the condition is often self-limiting. A few individuals have responded to PUVA or contact sensitisation induced by diphencyprone |

| Dermatitis herpetiformis | Dapsone is typically effective in 24 h, or sulfapyridine. Long-term gluten-free diet | Methaemoglobinaemia may complicate dapsone therapy |

| Hirsutism in women | Combined oestrogen–progestogen contraceptive pill: cyproterone plus ethinylestradiol (Dianette). Spironolactone, cimetidine have been used | Local cosmetic approaches: epilation by wax or electrolysis; depilation (chemical), e.g. thioglycollic acid, barium sulfide. The result of laser epilation is transient and may paradoxically induce excess hair growth in certain individuals |

| Hyperhidrosis | Astringents reduce sweat production, especially aluminium chloride hexahydrate. Antimuscarinics, e.g. glycopyrrolate (topical or systemic), may help and may be used with iontophoresis. Botulinum toxin can be used to provide temporary remission (3–4 months) and is most useful for the axilla. Sympathectomy is used occasionally but may be complicated by compensatory hyperhidrosis | The characteristic smell is produced by bacterial action, so cosmetic deodorants contain antibacterials rather than substances that reduce sweat |

| Impetigo | Topical antibiotics, e.g. mupirocin, fusidic acid | In severe cases (resistant organisms) systemic macrolide, cephalosporin antibiotics |

| Intertrigo | Cleansing lotions, powders to cleanse, lubricate and reduce friction. A dilute corticosteroid with anticandidal cream is often helpful | No evidence that new azoles are superior to nystatin |

| Larva migrans | Cryotherapy. Albendazole (single dose) or topical thiabendazole | |

| Lichen planus | Antipruritics (menthol); potent topical corticosteroid | PUVA or retinoids in severe cases |

| Lichen simplex (neurodermatitis) | Antipruritics (menthol); topical corticosteroid; sedating antihistamines | Occluding the lesion so as to prevent scratch–itch cycle to patient. Focused cognitive behaviour therapy may be helpful |

| Lupus erythematosus | Photoprotection (including against UVA) is essential. Potent adrenal corticosteroid topically or intralesionally. Hydroxychloroquine or mepacrine. Monitor for retinal toxicity when treatment is long term. Other agents include acetretin and auranofin | |

| Malignancies | Actinic keratoses and Bowen’s disease can be treated with topical 5-fluorouracil (skin irritation is to be expected) or cryotherapy. Imiquimod is a possible topical alternative. Extensive lesions may respond to photodynamic therapy: the skin is sensitised using a topical haematoporphyrin derivative, e.g. aminolaevulinic acid, and irradiated with a visible light or laser source. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in its early stages is best treated conservatively; PUVA will often clear lesions for several months or years; alternatives include topical nitrogen mustard, e.g. carmustine, radiotherapy and the retinoid bexarotene | |

| Nappy rash | Prevention: rid re-usable nappies of soaps, detergents and ammonia by rinsing. Change frequently and use an emollient cream, e.g. aqueous cream, to protect skin. Costly disposable nappies are useful but must also be changed regularly. Cure: zinc cream or calamine lotion plus above measures | |

| Onychomycosis | Confirm dermatophyte infection with microscopy and culture. Terbinafine, two pulses of itraconazole or 6–9 months of once-weekly fluconazole is used for fingernail onychomycosis. For toenail disease, terbinafine is used for 12–16 weeks; 3–4 pulses of itraconazole or fluconazole once per week for 9–15 months can be used | The newer oral antifungals have not been approved for use in children. Surgical removal of infected nail maybe required and reinfection is common |

| Pediculosis (lice) | Permethrin, phenothrin, carbaryl or malathion (anticholinesterases, with safety depending on more rapid metabolism in humans than in insects, and on low absorption) | Usually two applications 7 days apart to kill lice from eggs that survive the first dose. Physical measures including regular combing and keeping hair short are important |

| Pemphigus and pemphigoid | Milder cases can be treated with topical corticosteroids and tetracyclines. Systemic steroids and immunosuppressants (azathioprine, mycophenylate) are useful for severe disease. Plasmapheresis, IVIg and rituximab may also be useful for resistant cases | |

| Pityriasis rosea | Antipruritics and emollients as appropriate; UVB phototherapy | The disease is self-limiting |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | Topical therapies may include corticosteroids, tacrolimus. Systemic corticosteroids are usually effective. Immunosuppressives, e.g. ciclosporin, may be used for steroid-sparing effect. Some patients respond to dapsone, minocycline or clofazamine | |

| Rosacea | Topical metronidazole and systemic tetracycline. Retinoids are useful for severe cases | Control pustulation in order to prevent secondary scarring and rhinophyma |

| Scabies (Sarcoptes scabiei) | Permethrin dermal cream. Alternatives include benzyl benzoate or ivermectin (single dose), especially for outbreaks in closed communities. Crotamiton or calamine for residual itch. Topical corticosteroid to settle persistent hypersensitivity | Apply to all members of the household, immediate family or partner. Change underclothes and bedclothes after application |

| Seborrhoeic dermatitis: dandruff (Pityriasis capitis) | A proprietary shampoo with pyrithione, selenium sulfide or coal tar; ketoconazole shampoo in more severe cases. Occasionally a corticosteroid lotion may be necessary | |

| Tinea capitis | In children griseofulvin for 6–8 weeks is effective and safe. Terbinafine for 4 weeks is effective against Trichophyton spp. Microsporum will respond to 6 weeks’ therapy with terbinafine | Antifungal shampoos can reduce active shedding in patients treated with oral antifungals |

| Tinea pedis | Most cases will respond to tolnaftate or undecenoic acid creams. Allylamine (terbinafine) creams are possibly more effective than azoles in resistant cases | |

| Venous leg ulcers | Limb compression is the mainstay of therapy. Other agents including pentoxifylline and skin grafts are useful adjuncts to compression therapy | |

| Viral warts | All treatments are destructive and should be applied with precision. Salicylic acid in collodion daily. Many other caustic (keratolytic) preparations exist, e.g. salicylic and lactic acid paint or gel. For plantar warts, formaldehyde or glutaraldehyde; for plantar or anogenital warts, podophyllin (antimitotic). Follow the manufacturer’s instructions meticulously. If one topical therapy fails it is worth trying a different type. Topical imiquimod is an alternative for genital warts; it is irritant. Careful cryotherapy (liquid nitrogen) | Warts often disappear spontaneously. Cryotherapy can cause ulceration, damage the nail matrix and leave permanent scars |

Psoriasis

An emollient such as aqueous cream will reduce the inflammation. The proliferated cells may be eliminated by a dithranol (antimitotic) preparation applied accurately to the lesions (but not on the face or scalp) for 1 h and then removed as it is irritant to normal skin and stains skin, blond hair and fabrics. A suitable regimen may begin with 0.1% dithranol, increasing to 1%. Dithranol is available in cream bases or in Lassar’s paste (the preparations are not interchangeable). It is used daily until the lesions have disappeared and may produce prolonged remissions of psoriasis. Tar (antimitotic) preparations are used in a similar way, are less irritating to normal skin and are commonly used for psoriasis of the scalp.10

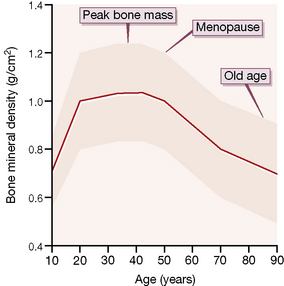

Calcipotriol and tacalcitol

are analogues of calcitriol, the most active natural form of vitamin D (see p. 551). They inhibit cell proliferation and encourage cell differentiation. Although they have less effect on calcium metabolism than does calcitriol, excessive use (more than 100 g/week) can raise the plasma calcium concentration.

Ciclosporin,

the systemic calcineurin inhibitor (see p. 523), has been instrumental in shifting the focus of psoriasis research from keratinocyte abnormalities to immune perturbations. It has a rapid onset of action and is useful in achieving remissions in all forms of psoriasis. Monitoring of blood pressure and renal function is mandatory. Severe adverse effects, including renal toxicity, preclude its being used as long-term suppressive therapy.

Acne

• Mild keratolytic (exfoliating, peeling) formulations unblock pilosebaceous ducts, e.g. benzoyl peroxide, sulphur, salicylic acid, azelaic acid.

• Systemic or topical antimicrobial therapy (tetracycline, erythromycin, lymecycline) is used over months (expect 30% improvement after 3 months). Bacterial resistance is not a problem; benefit is due to suppression of bacterial lipolysis of sebum, which generates inflammatory fatty acids. (Avoid minocycline because of adverse effects, including raised intracranial pressure and drug-induced lupus.)

• Vitamin A (retinoic acid) derivatives reduce sebum production and keratinisation. Vitamin A is a teratogen. Tretinoin (Retin-A) is applied topically (but not in combination with other keratolytics). Tretinoin should be avoided in sunny weather and in pregnancy. Benefit is seen in about 10 weeks. Adapalene, a synthetic retinoid, may be better tolerated as it is less irritant. Isotretinoin (Roaccutane) orally is highly effective (a single course of treatment to a cumulative dose of 100 mg/kg is curative in 94% of patients), but is known to be a serious teratogen; its use should generally be confined to the more severe cystic and conglobate cases, where other measures have failed. Fasting blood lipids should be measured before and during therapy (levels of cholesterol and triglycerides may rise). Women of childbearing potential should be fully informed of this risk, pregnancy-tested before commencement and use contraception for 4 weeks before, during and for 4 weeks after cessation.11 Other adverse effects are described, including mood change and severe depression.

• Hormone therapy. The objective is to reduce androgen production or effect by using (1) oestrogen, to suppress hypothalamic–pituitary gonadotrophin production, or (2) an antiandrogen (cyproterone). An oestrogen alone as initial therapy to get the acne under control or, in women, the cyclical use of an oral contraceptive containing 50 micrograms of oestrogen diminishes sebum secretion by 40%. A combination of ethinylestradiol and cyproterone (Dianette) orally is also effective in women (it has a contraceptive effect, which is desirable as the cyproterone may feminise a male fetus).

Bystryn J.C., Rudolph J. Pemphigus. Lancet. 2005;366:61–73.

Currie B.J., McCarthy J.S. Permethrin and ivermectin for scabies. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2010;362(8):717–725.

Hwang S.T., Janik J.E., Jaffe E.S., Wilson W.H. Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Lancet. 2008;371(9616):945–957.

James W.D. Acne. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2005;352(14):1463–1472.

Kaplan K.P. Chronic urticaria and angioedema. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2002;346(3):175–179.

Kullavanijaya P., Lim H.W. Photoprotection. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol.. 2005;52(6):937–958.

Madan V., Lear J.T., Szeimies R.M. Non-melanoma skin cancer. Lancet. 2010;375(9715):673–685.

Naldi L., Rebora A. Clinical practice. Seborrheic dermatitis. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2009;360(4):387–396.

Nestle F.O., Kaplan D.H., Barker J. Psoriasis. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2009;361(5):496–509.

Powell F.C. Rosacea. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2005;352(8):793–803.

Rosenfield R.L. Hirsutism. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2005;353(24):2578–2588.

Schwartz R.A. Superficial fungal infections. Lancet. 2004;364:1173–1182.

Smith C.H., Barker J.N.W.N. Psoriasis and its management. Br. Med. J.. 2006;333:380–384.

Stern R.S. Treatment of photoaging. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2004;350:1526–1534.

Thompson J.F., Scolyer R., Kefford R. Cutaneous melanoma. Lancet. 2005;365:687–701.

Williams H.C. Atopic dermatitis. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2005;352(22):2314–2324.

Yosipovitch G., Greaves M., Schmelz M. Itch. Lancet. 2003;361:690–694.

1 The chief ingredient of a mixture.

2 Talc is magnesium silicate. It must not be used for dusting surgical gloves as it causes granulomas if it gets into mounds or body cavities.

3 Astringents are weak protein precipitants, e.g. tannins, salts of aluminium and zinc.

4 In the UK, the Red Cross offers a free cosmetic camouflage service through hospital dermatology departments.

5 The distance from the tip of the index finger to the first skin crease.

6 McKenzie A W, Stoughton R B 1962 Method for comparing percutaneous absorption of steroids. Archives of Dermatology 86:608–610.

7 Kelly C J G, Ogilvie A, Evans J R et al 2001 Raised cortisol excretion rate in urine and contamination by topical steroids. British Medical Journal 322:594.

8 Data from The Medical Letter 1995;37:35.

9 Hardie R A, Savin J A 1979 Drug-induced skin diseases. British Medical Journal 1:935 (to whom we are grateful for the quotation and classification).

10 But are not without risk. A 46-year-old man whose psoriasis was treated with topical corticosteroids, UV light and tar was seen in the hospital courtyard bursting into flames. A small ring of fire began several centimetres above the sternal notch and encircled his neck. The patient promptly put out the fire. He admitted to lighting a cigarette just before the fire, the path of which corresponded to the distribution of the tar on his body (Fader D J, Metzman M S 1994 Smoking, tar, and psoriasis: a dangerous combination. New England Journal of Medicine 330:1541).

11 The risk of birth defect in a child of a woman who has taken isotretinoin when pregnant is estimated at 25%. Thousands of abortions have been performed in such women in the USA. It is probable that hundreds of damaged children have been born. There can be no doubt that there has been irresponsible prescribing of this drug, e.g. in less severe cases. The fact that a drug with such a grave effect is still permitted to be available is attributed to its high efficacy. In Europe, women of childbearing age must comply with a pregnancy prevention programme and be monitored monthly while on a course of isotretinoin. In the USA, patients and their doctors and pharmacists are required by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to register with the mandatory iPLEDGE distribution programme in order to receive this medication.