56 Drug-induced skin disorders

Diagnosis

It is often difficult to determine the cause of a drug-induced eruption because:

Definitive diagnosis of a drug-induced dermatosis would require drug re-challenge; however, this is not recommended due to the possibility of provoking a more severe reaction on second exposure (Li Wan Po and Kendall 2001).

Drug-induced skin disorders

Drug reactions causing changes to skin function

Abnormal photosensitivity

Drug-induced photosensitivity can be either phototoxic or photoallergic (Box 56.1). Phototoxic reactions, which are more common, resemble severe sunburn and can progress to blistering. They are dose dependent for both the drug and sunlight, occur within 5–15 h of taking the drug and subside quickly on drug withdrawal. Photoallergic rashes are usually eczematous, but may be lichenoid, urticarial, bullous or purpuric. They are not dose dependent and occur following exposure to normal amounts of sunlight exposure. The onset can be delayed by weeks or months, while recovery is often slow following drug withdrawal. Rarely, a photoallergic state can persist for years after the drug responsible has been discontinued.

Pigmentary changes

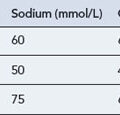

The skin’s colour can be altered by drugs: hyper-pigmentation, hypo-pigmentation and discoloration can all potentially be induced by a variety of medicines (see Fig. 56.1 and Table 56.1). Pigmentary changes can be widespread or localised. The most common examples of localised pigmentation are the facial blue–black pigmentation in individuals on amiodarone or minocyline, and melasma facial pigmentation occurring in some women taking the combined oral contraceptive pill. Generalised pigmentary change induced by drugs is rare, but can occur with chemotherapeutic agents such as bleomycin. This may have the appearance of generalised hyper-melanosis, or may take on a more flagellate appearance with multiple linear areas of hyper-pigmentation.

| Drug | Pigmentation |

|---|---|

| Amiodarone | Blue-Grey |

| Anticonvulsants | Brown |

| Antimalarials | Blue-Grey |

| β-Blockers | Brown |

| Imatinib | Hypo/Hyperpigmentation |

| Imipramine | Blue/Grey |

| Mepacrine | Blue/black |

| Methyldopa | Brown |

| Oral contraceptives | Brown spots/patches |

| Phenothiazines | Brown/Blue-Grey |

| Psoralens | Brown |

| Tetracyclines | Blue-Black |

Hair changes

Loss of hair

Drug-induced alopecia (Box 56.2) may be partial or complete. The temporal relationship between the introduction of the drug and the subsequent loss of hair depends on the part of the hair cycle with which the drug interferes. Cytotoxic drugs interfere with the ‘anagen’ or growth phase of the hair cycle, and so loss is rapid and complete; it begins shortly after administration of the drug and the effect is dose dependent and fortunately reversible, but a delay of several weeks is common before regrowth begins.

Excessive hair

Hirsutism is excessive hairiness, especially in women, in the male pattern of hair growth, while hypertrichosis is the growth of hair at sites not normally hairy. Both conditions can be drug induced and in some cases the same drug can produce both patterns of hair growth (see Box 56.2). The capacity of minoxidil to produce hypertrichosis was noted during early trials of this drug as an antihypertensive. It is infrequently used for its originally intended purpose, as it produces profound postural hypotension, but its most noticeable side effect has been exploited as a topical preparation for the treatment of male pattern baldness.

Mild drug-induced skin disorders

Drug-induced exanthems

A drug-induced exanthem (widespread rash) is the most common type of drug reaction in the skin. Exanthems are characterised by erythema (redness) and may be morbilliform (resembling measles) or maculopapular (a mixture of flat and raised areas) (see Fig. 56.2). Less frequently there may be blisters, which may be small (vesicles) or larger (>5 mm, bullae), and the skin may feel hot, burning or itchy.

Most drug-induced exanthems begin within 7 days of commencing a drug, the mechanism being a delayed (type IV) hypersensitivity (Burns et al., 2004). If the drug can be identified, it should be stopped, appropriate symptomatic relief instituted with antihistamines and topical steroids. A clear record of the reaction should be made in the patient’s notes. Both the patient and his primary care doctor should be made aware of the reaction for the purposes of future avoidance.

An exanthematous reaction commonly occurs following administration of ampicillin (or its derivatives, including amoxicillin) to patients suffering from glandular fever (infectious mononucleosis). It does not usually represent a true penicillin allergy, but a complex interplay between viral factors (infectious mononucleosis being caused by Epstein Barr virus) and drug epitopes (Burns et al., 2004). This reaction to the drug would not be expected to be seen in the same patient in the absence of the virus.

Urticaria and angioedema

Urticaria, also known as hives, describes the appearance of red, itchy weals on the skin (Fig. 56.3). Angioedema is a more serious, related condition in which the patient develops deep soft-tissue swellings, mostly notably on the face. Urticaria and angioedema can be either allergic, a reaction between an antigen and specific mast cell-bound IgE, or non-allergic. Drugs are recognised triggers of urticaria and angioedema (Box 56.3) and can also exacerbate pre-existing urticaria. The most important culprits are the NSAIDs and opiates, both of which lower the threshold for mast cell degranulation. ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), for example candesartan, can provoke angioedema in a susceptible individual.

Fixed drug eruptions

Fixed drug eruption is characterised by one or more inflammatory patches that recur at the same cutaneous or mucosal site(s) each time the patient is exposed to the offending drug (Fig. 56.4). The eruption usually involves the torso, hands, feet, face or genitalia, and is characterised by a deep red, circular, well-demarcated patch. They take between 2 and 24 h to develop following drug ingestion. On the first drug exposure, there is usually only one lesion, but subsequent exposure can result in multiple lesions.

The group of drugs with the potential to cause a fixed drug eruption is virtually limitless, but some of the drugs more commonly responsible are listed in Box 56.4.

Acneiform eruptions

A new class of anticancer drug, endothelial growth factor receptor antagonists, for example cetuximab, commonly produce an acneiform eruption. The papules and pustules which occur are more monomorphic than those seen in idiopathic acne. Interestingly, studies have shown that there is a positive correlation between the severity of the acneiform eruption and response of the cancer to the treatment (Saltz et al., 2003; Susman, 2004) Most drug-induced or drug-exacerbated acne can be managed with the same treatments as used in idiopathic acne, such as topical agents, oral tetracycline antibiotics, erythromycin, or in severe cases, oral retinoids. Examples of drugs which may cause an acneiform eruption are given in Box 56.5.

Psoriasiform eruptions

Drugs can either exacerbate psoriasis in predisposed patients or induce psoriasiform rashes in previously unaffected patients (see Box 56.6). The psoriasiform eruptions mimic psoriasis and are characterised by itchy, scaly red patches on the elbows, forearms, knees, legs and scalp. Drugs which have a well-established effect of worsening pre-existing psoriasis include β blockers, lithium, antimalarials and ACE inhibitors.

Lichenoid eruptions

Drug-induced lichenoid eruptions (see Box 56.7) resemble lichen planus, occurring as flat mauve lesions. However, they may be atypical, showing scaling and confluence. The lesions can be seen at any site, but are found mainly on the forearms, neck and on the inner surface of the thighs. The eruption resolves with drug withdrawal, with or without topical steroids, but post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation is often long lasting.

Severe drug-induced skin disorders

Erythema multiforme

EM is an eruption of target-like lesions which are characterised by concentric red and pale rings with, in severe cases, central blistering. EM typically occurs on the limbs rather than the trunk but mucous membrane surfaces, such as the eye, the mouth and the genital tract, may also become involved. A significant proportion of EM cases are caused by infection, particularly herpes simplex virus reactivation; however, in some patients, EM is triggered by a drug (see Box 56.8). Drug-induced EM will usually present within 2 weeks of starting a new medication. Once the responsible drug has been stopped, treatment is symptomatic with paracetamol, topical steroids and appropriate topical therapy for the mouth and other involved mucosal surfaces.

Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis

Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are terms used to describe a life-threatening, mucocutaneous drug hypersensitivity syndrome characterised by blistering and epidermal sloughing (Fig. 56.5). In SJS, there is epidermal detachment of <10% BSA, in TEN there is detachment of >30% of the BSA, while cases with 10–30% involvement are labelled SJS/TEN overlap. The systemic problems which accompany widespread epidermal loss such as high losses of heat and fluid, and the heightened risk of infection due to diminished barrier function can cause serious morbidity, similar to extensive burns. TEN carries a mortality rate of approximately 30%, but this can rise to 90% mortality in the presence of co-morbidities. HIV-infected patients and patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) have an enhanced risk of developing SJS/TEN. Drugs causing SJS/TEN are listed in Box 56.9.

Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms

Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS) is sometimes known as Drug-Induced Hypersensitivity Syndrome (DIHS) and is a distinct, severe and potentially fatal drug-induced skin disorder. The drugs commonly associated with this syndrome are listed in Box 56.10.

Typically, the dermatosis of DRESS is an extensive, inflammatory, maculo-papular exanthem. Other skin signs may also be present including pustules, purpura, blisters, target-like lesions and facial oedema (Fig. 56.6). To meet the diagnostic criteria, there will also be a haematological abnormality, either a raised eosinophil count (>1.5 × 109/L) or the presence of atypical lymphocytes on the blood film. There is prominent systemic involvement in DRESS, most commonly fever, lymph node enlargement and liver function abnormalities. Less typically, there is renal, pulmonary or cardiac involvement.

Acute Generalised Exanthematous Pustulosis

Acute Generalised Exanthematous Pustulosis (AGEP) describes a reaction pattern to a drug consisting of widespread sterile, monomorphic pustules studding the skin in a generalised fashion. Such patients are generally systemically unwell with a fever and the complications of generalised skin inflammation including excessive heat and fluid loss. The differential diagnosis would include pustular psoriasis. Although the condition is self-limiting, potent topical steroids may accelerate resolution. The drugs which can cause AGEP are summarised in Box 56.11.

Erythroderma and exfoliative dermatitis

Erythroderma is the term used to describe any pattern of drug reaction in the skin where more than 90% of the BSA is involved. This is usually an extension of a severe drug-induced exanthem. The erythrodermic patient often feels shivery and may have lymphadenopathy and fever. The large surface area involved in erythroderma leads to substantial losses of heat and fluid from the body. This puts the patient at risk of electrolyte imbalances, hypothermia, and with the loss of skin barrier function, infection. Admission to hospital is indicated in cases of erythroderma, and management is supportive, with intravenous fluids, warming measures, and treatment of infection. Topical corticosteroids are often prescribed but must be used with caution since significant amounts will be systemically absorbed across the erythrodermic skin. During recovery, the patient will desquamate, referred to as the exfoliative phase. Drugs commonly provoking this pattern of reaction are similar to those which cause a drug-induced exanthem (Box 56.12).

Lupus erythematosus

Syndromes indistinguishable from Lupus erythematosus (LE) may occur following drug administration (see Box 56.13) and can be accompanied by seroconversion to antinuclear antibody (ANA) positivity. Serological clearance of ANA may occur after drug withdrawal, but this may take months or years.

Vasculitis

Drugs are the cause of approximately 10% of cutaneous vasculitis cases and should be considered in any patient with small vessel vasculitis (Box 56.14). Withdrawal of the causative drug is often sufficient to resolve the clinical manifestations without the need for treatment with systemic corticosteroids or more powerful immunosuppressants.

Patient care

Answers

Answers

Answers

Answers

Case 56.5

An 85-year-old gentleman with rheumatoid arthritis, Mr DC, attends the local pharmacy with a persistent lesion on his left upper cheek, abutting the eyelid (Fig. 56.7), which has recently been bleeding. For the last 18 years, his rheumatoid arthritis has been treated with methotrexate. You know Mr DC is a retired naval officer, and his skin is severely sun damaged. He tells you he has had a number of basal cell carcinomas in the past and is concerned that this may be another.

Answers

Answers

Answers

Answers

Breathnach S.M. Drug eruptions. In Burns T., Breathnach S.M., Cox N., et al, editors: Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology, seventh ed, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2004.

Li Wan Po A., Kendall M.J. Causality assessment of adverse effects: when is rechallenge ethically acceptable. Drug Saf.. 2001;24:793-799.

Moncada B., Sahagun-Sanchez L.K., Torres-Alvarez B., et al. Molecular structure and concentration of melanin in the stratum corneum of patients with melasma. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed.. 2009;25:159-160.

Saltz L., Kies M., Abbruzzese J.L., et al. The presence and intensity of the cetuximab-induced acne-like rash predicts increased survival in studies across multiple malignancies. Proc. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol.. 2003;22:204. (Suppl; abstract 817)

Susman E. Rash correlates with tumour response after cetuximab. Lancet Oncol.. 2004;5:647.