Chapter 11 Drug dependence

• Sites and mechanisms of action.

• Routes of administration and effect.

Individual substances are discussed:

Introduction

The dividing line between legitimate use of drugs for social purposes and their abuse is indistinct, for it is not only a matter of which drug, but of the amount of drug and of whether the effect is antisocial or not. In the UK and elsewhere, the classification of drugs of abuse continues to be subject to controversy.1

Definitions

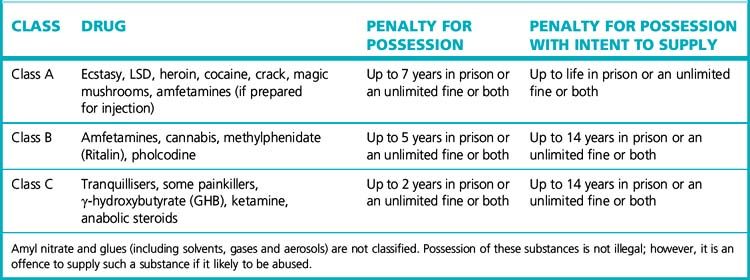

Dependence/abuse liability

of a drug is related to its capacity to produce immediate gratification, which may be a feature of the drug itself (amfetamine and heroin give rapid effect whereas tricyclic antidepressants do not), and its route of administration, in descending order: inhalation/intravenous, intramuscular/subcutaneous. Those drugs with high dependence/abuse liability are subject to regulation and non-medicinal use may be a criminal offence. The current UK list of controlled substances as proscribed by the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 is shown in Table 11.1. Readers will be aware that the list is subject to change according to social factors and political expediency.

Drives to drug abuse can be grouped as follows:

1. Relief of anxiety, tension and depression; escape from personal psychological problems; detachment from harsh reality; ease of social intercourse.

2. Rebellion against or despair about orthodox social values and the environment. Fear of missing something, and conformity with own social subgroup (the young, especially).

3. Fun, amusement, recreation, excitement, curiosity (the young, especially).

4. Improvement of performance in competitive sport (a distinct motivation, see below).

General patterns of use

Patterns of drug dependence differ with age. Men are more commonly involved than women. Patterns change as drugs come in and out of vogue. The general picture in the UK is shown in Table 11.2. Data on illicit drug use in the UK are provided from a number of sources but up-to-date information on prevalence and patterns of usage can be obtained from the annual British Crime Survey. Data from the 2008/2009 survey indicate that one in three people between the ages of 16 and 59 had ever used illicit drugs while 1 in 10 had used an illicit substance in the previous year. The survey also allows observations on the trends in illicit drug use over time, as shown in Table 11.3.

| Age group | |

|---|---|

| Under 14 years | Volatile inhalants, e.g. solvents of glues, aerosol sprays, vaporised (by heat) paints, ‘solvent or substance’ abuse, ‘glue sniffing’ |

| Age 14–16 years | Cannabis, ecstasy, cocaine |

| Age 16–35 years | Hard-use drugs, chiefly heroin, cocaine and amfetamines (including ‘ecstasy’). Surviving users tend to reduce or relinquish heavy use as they enter middle age Also cannabis, magic mushrooms |

| Any age | Alcohol, tobacco, mild dependence on hypnotics and tranquillisers, occasional use of LSD and cannabis |

Table 11.3 Trends in drug use in UK (Information derived from 2008/2009 British Crime Survey)

| Increased use | Decreased use | Stable use |

|---|---|---|

| Between 1996 and 2008/2009 | ||

Sites and mechanisms of action

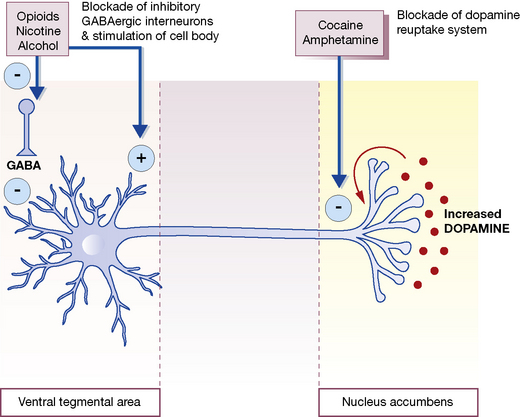

Drugs of abuse are extremely diverse in their chemical structures, mechanisms of action and anatomical and cellular targets. Nevertheless, there is an emerging consensus that addictive drugs possess a parallel ability to modulate the brain reward system that is key to activities that are vital for survival (e.g. eating and sexual behaviour). Of particular relevance is the medial forebrain bundle (MFB) that connects the ventral tegmental area and the nucleus accumbens. Natural and artificial rewards (including drugs of abuse) have been shown to activate the dopaminergic neurones within the MFB. It seems that drugs of abuse can converge on common neural mechanisms in these areas to produce acute reward and chronic alterations in reward systems that lead to addiction. This is summarised in Figure 11.1.

Route of administration and effect

With the intravenous route or inhalation, much higher peak plasma concentrations can be reached than with oral administration. This accounts for the ‘kick’ or ‘flash’ that abusers report and which many seek, likening it to sexual orgasm or better. As an addict said, ‘The ultimate high is death’, and it has been reported that, when hearing of someone dying from an overdose, some addicts will seek out the vendor as it is evident he is selling ‘really good stuff’.3

Prescribing for drug dependence

In the UK, supply of certain drugs for the purpose of sustaining addiction or managing withdrawal is permitted under strict legal limitations, usually by designated doctors. Guidance about the responsibilities and management of addiction is available.4 By such procedures it is hoped to limit the expansion of the illicit market, and its accompanying crime and dangers to health, e.g. from infected needles and syringes. The object is to sustain young (usually) addicts, who cannot be weaned from drug use, in reasonable health until they relinquish their dependence (often over about 10 years).

Treatment of dependence

Withdrawal of the drug

While obviously important, this is only a step on what can be a long and often disappointing journey to psychological and social rehabilitation, e.g. in ‘therapeutic communities’. A heroin addict may be given methadone as part of a gradual withdrawal programme (see p. 286), for this drug has a long duration of action and blocks access of injected opioid to the opioid receptor so that if, in a moment of weakness, the subject takes heroin, the ‘kick’ is reduced. More acutely, the physical features associated with discontinuing high alcohol use may be alleviated by chlordiazepoxide given in decreasing doses for 7–14 days. Sympathetic autonomic overactivity can be treated with a β-adrenoceptor blocker.

Mortality

Young illicit users by intravenous injection (heroin, benzodiazepines, amfetamine) have a high mortality rate. Death follows either overdose or the occurrence of septicaemia, endocarditis, hepatitis, AIDS, gas gangrene, tetanus or pulmonary embolism from the contaminated materials used without aseptic precautions (schemes to provide clean equipment mitigate this). Smugglers of illicit cocaine or heroin sometimes carry the drug in plastic bags concealed by swallowing or in the rectum (‘body packing’). Leakage of the packages, not surprisingly, may have a fatal result.5

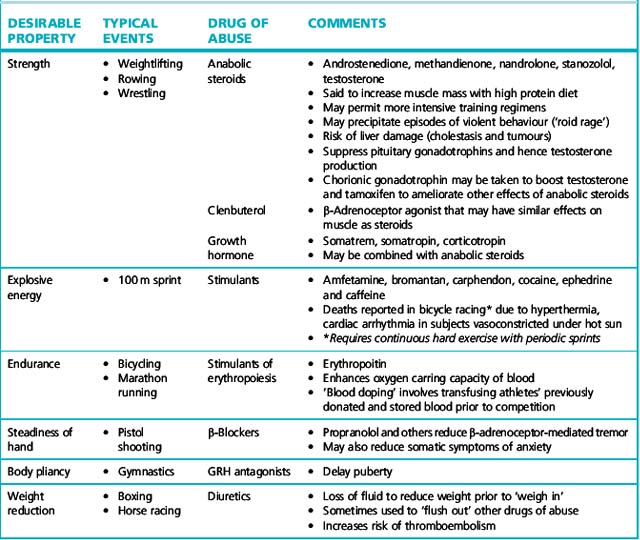

Drugs and sport

Drugs are frequently used to enhance performance in sport, although efficacy is largely undocumented. Detection can be difficult when the drugs or metabolites are closely related to or identical with endogenous substances, and when the drug can be stopped well before the event without apparent loss of efficacy. In order to get round this problem, regulatory bodies set ‘benchmarks’. Detection of levels of the naturally occurring compound above this level indicates potential doping. There remain unresolved issues at where exactly these benchmarks should be set. Research continues for improved methods of detecting drugs used in sport. The use of mass spectrometry6 to detect the isotope content of compounds might enable natural and synthetic steroids to be differentiated. Other indirect methods are employed. Testosterone and its related compound, epitestosterone, are both eliminated in urine. The ratio of testosterone to epitestosterone increases with use of anabolic steroids and can be used to detect anabolic steroid use.

Performance enhancement

Table 11.4 summarises the mechanisms by which drugs can enhance performance in various sports; naturally, these are proscribed by the authorities (International Olympic Committee (IOC) Medical Commission, and the governing bodies of individual sports).

For any minor injuries sustained during athletic training, NSAIDs and corticosteroids (topical, intra-articular) suppress symptoms and allow the training to proceed maximally. Their use is allowed subject to restrictions about route of administration, but strong opioids are disallowed. Similarly, the IOC Medical Code defines acceptable and unacceptable treatments for relief of cough, hay fever, diarrhoea, vomiting, pain and asthma. Doctors should remember that they may get their athlete patients into trouble with sports authorities by inadvertent prescribing of banned substances. The British National Formulary provides general advice for UK prescribers (further information and advice, including the status of specific drugs in sport, can be obtained at http://www.uksport.gov.uk).

Ethyl alcohol (ethanol)

Pharmacokinetics

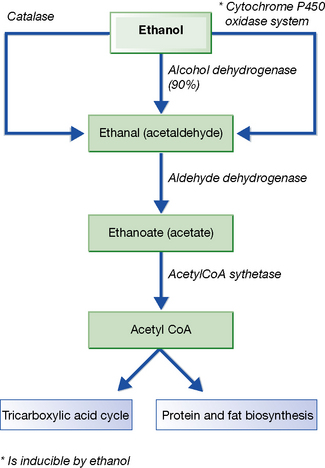

About 95% of absorbed alcohol is metabolised by the liver, the remainder being excreted in the breath, urine and sweat; convenient methods of estimation of alcohol in all these media are available (Fig. 11.2).

Inter-ethnic variation is recognised in the ability to metabolise alcohol (see p. 145).

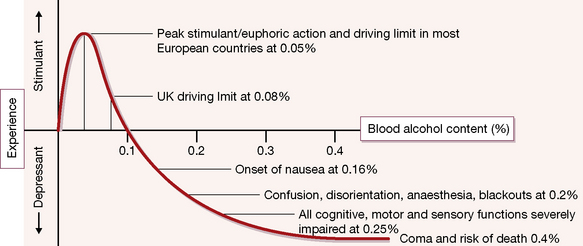

The blood concentration of alcohol (see Fig. 11.3) has great medicolegal importance. Alcohol in alveolar air is in equilibrium with that in pulmonary capillary blood, and reliable, easily handled measurement devices (breathalysers) are used by police at the roadside on both drivers and pedestrians.7

Pharmacodynamics

All of these are clearly highly undesirable effects when a person is in a position where failure to perform well may be dangerous. Some other important physiological and metabolic effects of acute alcohol ingestion are described in Table 11.5.

Table 11.5 Other physiological, pathological and metabolic effects of acute alcohol ingestion

| Effect | Comments |

|---|---|

| Vomiting |

People of Asian origin (particularly Japanese) develop flushing, headache and nausea after what are small doses

May be due to slow metabolism of toxic acetaldehyde by variant forms of alcohol dehydrogenase

Chronic consumption

The effects of chronic alcohol usage are summarised in Table 11.6. Reversal of all or most of the above effects is usual in early cases if alcohol is abandoned. In more advanced cases the disease may be halted (except cancer), but in severe cases it may continue to progress. When wine rationing was introduced in Paris during the Second World War, deaths from hepatic cirrhosis dropped to about one-sixth of the previous level; 5 years after the war they had regained their former level.

Table 11.6 Physiological, pathological and metabolic effects of chronic alcohol ingestion

| Effect | Comments |

|---|---|

| Organ damage |

• Male fertility is reduced (lower testosterone, reduced sperm count and function)

• Pregnancy is unlikely in alcoholic women with amenorrheoa due to liver injury

• The spontaneous miscarriage rate doubles in second trimester by consumption of 1–2 units per day

• The profound effects on developing fetus and baby are discussed in the text

Car driving and alcohol

Alcohol is a factor in as many as 50% of motor accidents. For this reason, the compulsory use of a roadside breath test is acknowledged to be in the public interest. In the UK, having a blood concentration exceeding 80 mg alcohol per 100 mL blood (17.4 mmol/L)8 while in charge of a car is a statutory offence. At this concentration, the liability to accident is about twice normal. Other countries set lower limits, e.g. Nordic countries,9 some states of the USA, Australia, Greece.

Alcohol-dependence syndrome

• Acute effect of alcohol appears to be blockade of NMDA receptors for which the normal agonist is glutamate, the main excitatory transmitter in the brain.

• Chronic exposure increases the number of (excitatory) NMDA receptors and also ‘L type’ calcium channels, while the action of the (inhibitory) GABAA neurotransmitter is reduced.

• The resulting excitatory effects may explain the anxiety, insomnia and craving that accompanies sudden withdrawal of alcohol (and may explain why resumption of drinking brings about relief, perpetuating dependence).

Treatment of alcohol dependence

Psychosocial support is more important than drugs, which nevertheless may help.

Safe limits for chronic consumption

For men not more than 21 units per week (and not more than 4 units in any 1 day); for women not more than 14 units per week (and not more than 3 units in any 1 day).10

Consistent drinking of more than these amounts carries a progressive risk to health. In other societies recommended maxima are higher or lower. Alcoholics with established cirrhosis have usually consumed about 23 units (230 mL; 184 g) daily for 10 years. Heavy drinkers may develop hepatic cirrhosis at a rate of about 2% per annum. The type of drink (beer, wine, spirits) is not particularly relevant to the adverse health consequences; a standard bottle of spirits (750 mL) contains 300 mL (240 g) of alcohol (i.e. 40% by volume). Most people cannot metabolise more than about 170 g/day. On the other hand, regular low alcohol consumption may confer benefit: up to one drink per day appears not to impair cognitive function in women and may actually decrease the risk of cognitive decline,11 and light-to-moderate alcohol consumption may reduce risk of dementia in people aged 55 years or more.12

The curve that relates mortality (vertical axis) to alcoholic drink consumption (horizontal axis) is J-shaped. As consumption rises above zero the all-cause mortality declines, then levels off, and then progressively rises. The benefit is largely a reduction of deaths due to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease for regular drinkers of 1–2 units per day for men aged over 40 years and postmenopausal women. Consuming more than 2 units a day does not provide any major additional health benefit. The mechanism may be an improvement in lipoprotein (HDL/LDL) profiles and changes in haemostatic factors.13 The effect appears to be due mainly to ethanol itself, but non-ethanol ingredients (antioxidants, phenols, flavinoids) may contribute. The rising (adverse) arm of the curve is associated with known harmful effects of alcohol (already described), but also, for example, with pneumonia (which may be secondary to direct alcohol effects, or with the increased smoking of alcohol users).

Alcohol in pregnancy and breast feeding

Alcohol and other drugs

The important interactions of alcohol with other drugs are shown in Table 11.7.

Table 11.7 Important interactions of alcohol with other drugs

| Drug class | Example | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Antibiotics | Metronidazole, trimethoprim, cephalosporins | Disulfuram like action resulting in facial flushing, headaches, tachycardia and feinting |

| Vasodilators | GTN | Increased adverse effects with risk of hypotension and falls |

| Opioid analgesics | morphine | Exacerbation of adverse effects with increased sedation |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents | Ibuprofen, naproxen | Increased risk of GI ulceration and bleeding |

| Hypoglycaemic agents | Insulin, sulphonylureas | Increased hypoglycaemic risk |

| Anticoagulants | warfarin | Acute alcohol ingestion inhibits metabolism and increases bleeding risk Chronic administration induces metabolism and reduces efficacy |

| Anticonvulsants | phenytoin | Acute alcohol ingestion increases availability and side effect profile Chronic administration induces metabolism and can increase seizure frequency |

| Anaesthetics | propofol | Chronic alcohol ingestion results in resistance to effects of anaesthetic agents such that increased doses are required. Chronic consumption may increase risk of liver damage from halothane and enflurane |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | amitriptyline | Acute and chronic ingestion can increase availability and worse sedation and side effects |

Other cerebral depressants

Alcohol, benzodiazepines, clomethiazole and barbiturates broadly possess the common action of influencing GABA neurotransmission through the GABAA–benzodiazepine receptor complex (see p. 339 and Fig. 20.5) and all readily induce tolerance and dependence.

Tobacco

In 1492, the explorer Christopher Columbus observed Native Americans using the dried leaves of the tobacco plant (later named Nicotiana16) for pleasure and also to treat ailments.

Following its introduction to Europe in the 16th century, tobacco enjoyed popularity to the extent of being considered a panacea, being called ‘holy herb’ and ‘God’s remedy’.17 Only relatively recently have the harmful effects of tobacco come to light, notably from mortality studies among British doctors.18 Current estimates hold that there are more than a billion smokers worldwide. In 1990 there were 3 million smoking-related deaths per year, projected to reach 10 million by 2030.19

Composition

Environmental tobacco smoke has been classified as a known human carcinogen in the USA since 1992.20 Although the risks of passive smoking are naturally smaller, the number of people affected is large. One study estimated that breathing other people’s smoke increases a person’s risk of ischaemic heart disease by a quarter.21 Tobacco smoke contains 1–5% carbon monoxide and habitual smokers have 3–7% (heavy smokers as much as 15%) of their haemoglobin as carboxyhaemoglobin, which cannot carry oxygen. This is sufficient to reduce exercise capacity in patients with angina pectoris. Chronic carboxyhaemoglobinaemia causes polycythaemia (which increases the viscosity of the blood). Substances carcinogenic to animals (polycyclic hydrocarbons and nicotine-derived N-nitrosamines) have been identified in tobacco smoke condensates from cigarettes, cigars and pipes. Polycyclic hydrocarbons are responsible for the hepatic enzyme induction that occurs in smokers.

Tobacco dependence

Nicotine possesses all the characteristics of a drug of dependence:

• It modulates dopamine activity in the midbrain, particularly in the mesolimbic system, which promotes the development and maintenance of reward behaviour.

• Nicotine inhaled in cigarette smoke reaches the brain in 10–19 s.

• Short elimination t½ requires regular smoking to maintain the effect.

• Inhaling cigarette smoke is thus an ideal drug delivery system to institute behavioural reinforcement and then dependence.

A report on the subject concludes that most smokers do not do so from choice but because they are addicted to nicotine.22

Acute effects of smoking tobacco

• Increased airways resistance occurs due to the non-specific effects of submicronic particles, e.g. carbon particles less than 1 micrometre across. The effect is reflex: even inert particles of this size cause bronchial narrowing sufficient to double airways resistance; this is insufficient to cause dyspnoea, though it might affect athletic performance. Pure nicotine inhalations of concentration comparable to that reached in smoking do not increase airways resistance.

• Ciliary activity, after transient stimulation, is depressed, and particles are removed from the lungs more slowly.

• Carbon monoxide absorption may be clinically important in the presence of coronary heart disease (see above), although it is physiologically insignificant in healthy young adults.

Nicotine pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Nicotine is an agonist to receptors at the ends of peripheral cholinergic nerves whose cell bodies lie in the CNS: i.e. it acts at autonomic ganglia and at the voluntary neuromuscular junction (see Fig. 22.1). This is what is meant by the term ‘nicotine-like’ or ‘nicotinic’ effect. Higher doses paralyse at the same points. The CNS is stimulated, including the vomiting centre, both directly and via chemoreceptors in the carotid body. Tremors and convulsions may occur. As with the peripheral actions, depression follows stimulation.

Metabolic rate. Nicotine increases the metabolic rate only slightly at rest,24 but approximately doubles it during light exercise (occupational tasks, housework). This may be due to increase in autonomic sympathetic activity. The effect declines over 24 h on stopping smoking and accounts for the characteristic weight gain that is so disliked and which is sometimes given as a reason for continuing or resuming smoking. Smokers weigh 2–4 kg less than non-smokers (not enough to be a health issue).

Effects of chronic smoking

• The risk of death from lung cancer is related to the number of cigarettes smoked and the age of starting.

• It is similar between smokers of medium (15–21 mg), low (8–14 mg) and very low (<0.5 mg) tar cigarettes.

• Giving up smoking reduces the risk of death progressively from the time of cessation.25

The adverse effects of cigarette smoke on the lungs may be separated into two distinct conditions:

• Chronic mucus hypersecretion, which causes persistent cough with sputum and fits with the original definition of simple chronic bronchitis. This condition arises chiefly in the large airways, usually clears up when the subject stops smoking and does not on its own carry any substantial risk of death.

• Chronic obstructive lung disease, which causes difficulty in breathing chiefly due to narrowing of the small airways, includes a variable element of destruction of peripheral lung units (emphysema), is progressive and largely irreversible and may ultimately lead to disability and death.

Both conditions can coexist in one person and they predispose to recurrent acute infective illnesses.

Women and smoking

• The risks of spontaneous abortion, stillbirth and neonatal death are approximately doubled.

• The placenta is heavier in smoking than non-smoking women and its diameter larger, possibly from adaptations to lack of oxygen due to smoking, secondary to raised concentrations of circulating carboxyhaemoglobin.

• The babies of women who smoke are approximately 200 g lighter than those of women who do not smoke.

• They have an increased risk of death in the perinatal period which is independent of other variables such as social class, level of education, age of mother, race or extent of antenatal care.

• The increased risk rises two-fold or more in heavy smokers and appears to be accounted for entirely by the placental abnormalities and the consequences of low birth-weight.

• Ex-smokers and women who give up smoking in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy have offspring whose birth-weight is similar to that of the children of women who have never smoked.

Starting and stopping use

Aids to giving up

is principally responsible for the addictive effects of tobacco smoking, and is therefore a logical pharmacological aid to quitting. It is available in a number of formulations, including chewing gum, transdermal patch, oral and nasal spray. When used casually without special attention to technique, nicotine formulations have proved no better than other aids but, if used carefully and withdrawn as recommended, the accumulated results are almost two times better than in smokers who try to stop without this assistance.27

Restlessness during terminal illness may be due to nicotine withdrawal and go unrecognised; a nicotine patch may benefit a (deprived) heavy smoker. Nicotine transdermal patches may cause nightmares and abnormal dreaming, and skin reactions (rash, pruritus and ‘burning’ at the application site). Immunotherapy, using a vaccine of antibodies specific for nicotine, holds promises to prevent relapse in abstinent smokers or for adolescents to avoid initiation.28

Psychodysleptics or hallucinogens

Lysergide (LSD)

(ecstasy, MDMA: methylenedioxymethamfetamine) is structurally related to both mescaline and amfetamine. It has a t½ of about 8 h. It is popular as a dance drug at ‘rave’ parties. An estimated 5% of the American adult population have used tenamfetamine at least once.29 Popular names reflect the appearance of the tablets and capsules and include White Dove, White Burger, Red and Black, Denis the Menace. Tenamfetamine stimulates central and peripheral α- and β-adrenoceptors; thus the pharmacological effects are compounded by those of physical exertion, dehydration and heat.

In susceptible individuals (poor metabolisers who exhibit the CYP450 2D6 polymorphism) a severe and fatal idiosyncratic reaction may occur with fulminant hyperthermia, convulsions, disseminated intravascular coagulation, rhabdomyolysis, and acute renal and hepatic failure. Treatment includes activated charcoal, diazepam for convulsions, β-blockade (atenolol) for tachycardia, α-blockade (phentolamine) for hypertension, and dantrolene if the rectal temperature exceeds 39°C. In chronic users, positive emission tomographic (PET) brain scans show selective dysfunction of serotonergic neurones, raising concerns that neurodegenerative changes accompany long-term use of MDMA.30

(‘angel dust’) is structurally related to pethidine. It induces analgesia without unconsciousness, but with amnesia, in humans (dissociative anaesthesia, see p. 301). It acts as an antagonist at NMDA glutamate receptors. It can be insufflated as a dry powder or smoked (cigarettes are dipped in phencyclidine dissolved in an organics solvent). Phencyclidine overdose can cause agitation, abreactions, hallucinations and psychosis, and if severe can result in seizures, coma, hyperthermia, muscular rigidity and rhabdomyolysis.

Methylxanthines (xanthines)

• Tea contains caffeine and theophylline.

• Cocoa and chocolate contain caffeine and theobromine.

• The cola nut (‘cola’ drinks) contains caffeine.

• Theobromine is weak and of no clinical importance (although responsible for the toxicity of chocolate when ingested by dogs).

Other effects

Caffeine affects sleep of older people more than it does that of younger people. Onset of sleep (sleep latency) is delayed, bodily movements are increased, total sleep time is reduced and there are increased awakenings. Tolerance to this effect does not occur, as is shown by the provision of decaffeinated coffee.31

Cannabis

Cannabis is obtained from the annual plant Cannabis sativa (hemp) and its varieties Cannabis indica and Cannabis americana. The preparations that are smoked are called marijuana (also grass, pot, weed) and consist of crushed leaves and flowers. There is a wide variety of regional names, e.g. ganja (India, Caribbean), kif (Morocco), dagga (Africa). The resin scraped off the plant is known as hashish (hash). The term cannabis is used to include all the above preparations. As most preparations are illegally prepared it is not surprising that they are impure and of variable potency. The plant grows wild in the Americas,32 Africa and Asia. It can also be grown successfully in the open in the warmer southern areas of Britain. Some 27% of the adult UK population report having used cannabis in their lifetime.

Pharmacokinetics

Of the scores of chemical compounds that the resin contains, the most important are the oily cannabinoids, including tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which is the main psychoactive ingredient. Samples of resin vary greatly in the amounts and proportions of these cannabinoids according to their country of origin. As the sample ages, its THC content declines. THC content of samples can vary from 8% to almost zero. Smoke from a cannabis cigarette (the usual mode of use is to inhale and hold the breath to allow maximum absorption) delivers 25–50% of the THC content to the respiratory tract. THC (t½ 4 days) and other cannabinoids undergo extensive biotransformation in the body, yielding scores of metabolites, several of which are themselves psychoactive. They are extremely lipid-soluble and are stored in body fat from which they are slowly released.33 Hepatic drug-metabolising enzymes are inhibited acutely but may also be induced by chronic use of crude preparations.

Pharmacodynamics

Cannabinoids and skilled tasks

e.g. car driving. General performance in both motor and psychological tests deteriorates, more in naive than in experienced subjects. Effects may be similar to alcohol, but experiments in which the subjects are unaware that they are being tested (and so do not compensate voluntarily) are difficult to do, as with alcohol. In a placebo-controlled trial of airline pilots in a flight simulator, performance was impaired for up to 50 h after the pilots smoked a joint containing THC 20 mg (a relatively low dose by current standards).34

Uses

Issues of cannabis and cannabis-based medicines were the subject of a working party report35 whose main conclusions were:

• Inhibition of cannabinoid action can be used to help obese patients to lose weight. The first of a new class of CB1-receptor antagonists, rimonabant, reduced body-weight and improved cardiovascular risk factors (HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, insulin resistance) in obese patients over 1 year.36 It may cause nausea and depression and is contraindicated in pregnancy.

• In neuropathic pain, i.e. due to damaged neural tissue, data from well-controlled but limited duration trials suggest that THC is similar to codeine in potency, is safe and is not associated with tolerance or dependence.

• Cannabinoids regulate bone mass, and cannabinoid receptor antagonists may have a role in the treatment of osteoporosis.

• Data on the value of cannabis preparations for multiple sclerosis are not conclusive, although there is some support for a therapeutic effect.

Adverse effects

Chronic

There is tendency to paranoid thinking. Cognitive defect occurs and persists in relation to the duration of cannabis use. High or habitual use can be followed by a psychotic state; this is usually reversible, quickly with brief periods of cannabis use, but more slowly after sustained exposures. Evidence indicates that chronic use may precipitate psychosis in vulnerable individuals.37 Continued heavy use can lead to tolerance, and a withdrawal syndrome (depression, anxiety, sleep disturbance, tremor and other symptoms). Abandoning cannabis is difficult for many users.

Psychostimulants

Cocaine

For use it is vaporised by heat (it pops or cracks) in a special glass ‘pipe’; or mixed with tobacco in a cigarette. Inhalation with breath-holding allows pulmonary absorption that is about as rapid as an intravenous injection. It induces an intense euphoric state. The mouth and pharynx become anaesthetised. (See Local anaesthetic action of cocaine, p. 304.) Intravenous use gives the expected rapid effect (kick, flash, rush). Cocaine may be mixed with heroin (as ‘speedball’).

Amfetamines

is manifested by excitement and peripheral sympathomimetic effects. Convulsions may occur in acute or chronic overuse; a state resembling hyperactive paranoid schizophrenia with hallucinations develops. Hyperthermia occurs with cardiac arrhythmias, vascular collapse, intracranial haemorrhage and death. Treatment is chlorpromazine with added antihypertensive, e.g. labetalol, if necessary; these provide sedation and β-adrenoceptor blockade (but not a β-blocker alone, see p. 408), rendering unnecessary the optional enhancement of elimination by urinary acidification.

Volatile substance abuse

A 17-year-old boy was offered the use of a plastic bag and a can of hair spray at a beach party. The hair spray was released into the plastic bag and the teenager put his mouth to the open end of the bag and inhaled … he exclaimed, ‘God, this stuff hits ya fast!’ He got up, ran 100 yards, and died.38

Aubin H.J., Karila L., Reynaud M. Pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation: present and future. Curr. Pharm. Des.. 2011;17(14):143–150.

Clark S. Personal account: on giving up smoking. Lancet. 2005;365:1855.

Doll R. One for the heart. Br. Med. J.. 1997;315:1664–1668.

Edwards R. The problem of tobacco smoking. Br. Med. J.. 2004;328:217–219. (and subsequent articles in this series on the ‘ABC of Smoking Cessation’)

Fergusson D.M., Poulton R., Smith P.F., Boden J.M. Cannabis and psychosis. Br. Med. J.. 2006;322:172–176.

Flower R. Lifestyle drugs: pharmacology and the social agenda. Trends Pharmacol. Sci.. 2004;25(4):182–185.

Gerada C. Drug misuse: a review of treatments. Clin. Med. (Northfield Il). 2005;5(1):69–73.

Gordon R.J., Lowy F.D. Bacterial infections in drug users. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2005;353(18):1945–1954.

Jamrozik K. Estimate of deaths attributable to passive smoking among UK adults: database analysis. Br. Med. J.. 2005;330:812–815.

Kahan M., Srivastava A., Ordean A., Cirone S. Buprenorphine: new treatment of opioid addiction in primary care. Can. Fam. Physician. 2011;57(3):281–289.

Kosten T.R., O’Connor P.G. Management of drug and alcohol withdrawal. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2003;348(18):1786–1795.

Lange R.A., Hillis L.D. Cardiovascular complications of cocaine use. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2001;345(5):351–358.

Malaiyandi V., Sellers E.M., Tyndale R.F. Implications of CYP2A6 genetic variation for smoking behaviours and nicotine dependence. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther.. 2005;77(3):145–158.

Minozzi S., Amato L., Vecchi S., et al. Oral naltrexone maintenance treatment for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. 2011;13:4.

Nutt D., King L.A., Saulsbury W., Blakemore C. Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse. Lancet. 2007;369:1047–1053.

Ricaurte G.A., McCann U.D. Recognition and management of complications of new recreational drug use. Lancet. 2005;365:2137–2145. (see also p. 2146, the anonymous Personal Account: GHB – sense and sociability)

Snead O.C., Gibson K.M. γ-hydroxybutyric acid. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2005;352(26):2721–2732.

1 MacDonald R, Das A 2006 UK classification of drugs of abuse: an un-evidence-based mess. Lancet 368:559–561.

2 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, American Psychiatric Association 2007.

3 Bourne P 1976 Acute Drug Abuse Emergencies. Academic Press, New York.

4 See Department of Health 1999 Drug Misuse and Dependence – Guidelines on Clinical Management. The Stationery Office, London (3rd impression 2005).

5 A 49-year-old man became ill after an international flight. An abdominal radiograph showed a large number of spherical packages in his gastrointestinal tract, and body-packing was suspected. As he had not defaecated, he was given liquid paraffin. He developed ventricular fibrillation and died. Post-mortem examination showed that he had ingested more than 150 latex packets, each containing 5 g cocaine, making a total of almost 1 kg (lethal oral dose 1–3 g). The liquid paraffin may have contributed to his death as the mineral oil dissolves latex. Sorbitol or lactulose with activated charcoal should be used to remove ingested packages, or surgery if there are signs of intoxication. (Visser L, Stricker B, Hoogendoorn M, Vinks A 1998 Do not give paraffin to packers. Lancet 352:1352.)

6 A highly sensitive technique that can identify minor differences between molecules. It is based on the principle that ions passing at high velocity through an electrical field at right angles to their motion will deviate from a straight line according to their mass and charge; the heaviest will deviate least, the lightest most.

7 An arrested man was told, in a police station by a doctor, that he was drunk. The man asked, ‘Doctor, could a drunk man stand up in the middle of this room, jump into the air, turn a complete somersault, and land down on his feet?’ The doctor was injudicious enough to say, ‘Certainly not’ – and was then and there proved wrong (Worthing C L 1957 British Medical Journal i:643). The introduction of the breathalyser, which has a statutory role only in road traffic situations, has largely eliminated such professional humiliations.

8 Approximately equivalent to 35 micrograms alcohol in 100 mL expired air (or 107 mg in 100 mL urine). In practice, prosecutions are undertaken only when the concentration is significantly higher to avoid arguments about biological variability and instrumental error. Urine concentrations are little used as the urine is accumulated over time and does not provide the immediacy of blood and breath.

9 In 1990 Sweden lowered the limit to 20 mg/100 mL, which has been approached by ingestion of glucose which becomes fermented by gut flora in some people – the ‘autobrewery’ syndrome.

10 Report of an Inter-Departmental Working Group 1995 Sensible Drinking. Department of Health, London.

11 Stampfer M J, Kang J H, Chen J et al 2005 Effects of moderate alcohol consumption on cognitive function in women. New England Journal of Medicine 352:245–253.

12 Ruitenberg A, van Swieten J C, Witteman J C M et al 2002 Alcohol consumption and the risk of dementia: the Rotterdam study. Lancet 359:281–286.

13 Rimm E B, Williams P, Fosher K et al 1999 Moderate alcohol intake and lower risk of coronary heart disease: meta-analysis of effects on lipids and haemostatic factors. British Medical Journal 319:1523–1528.

14 Mukherjee R A S, Hollins A, Turk J 2006 Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: an overview. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 99:298–302.

15 For pictures see Streissguth A P, Clarren S K, Jones K L 1985 Natural history of the fetal alcohol syndrome: a 10-year follow-up of eleven patients. Lancet ii:85–91.

16 After the French diplomat, Jean Nicot de Villemain, who introduced tobacco to Europe.

17 Dickson S A 1954 Panacea or Precious Bane. Tobacco in 16th Century Literature. New York Public Library, New York. Quoted in: Charlton A 2004 Medicinal uses of tobacco in history. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 97:292–296.

18 Doll R, Hill A B 1954 The mortality of doctors in relation to their smoking habits. British Medical Journal i:1451–1455.

19 Peto R, Lopez A D, Boreham A et al 1996 Mortality from smoking worldwide. British Medical Bulletin 52:12–21.

20 Environmental Protection Agency (EPA 1992A/600/6–90/006 F).

21 Law M R, Morris J K, Wald N J 1997 Environmental tobacco smoke exposure and ischaemic heart disease: an evaluation of the evidence. British Medical Journal 315:973–988.

22 Tobacco Advisory Group, Royal College of Physicians 2000 Nicotine Addiction in Britain. Royal College of Physicians, London.

23 Fatal nicotine poisoning has been reported from smoking, from swallowing tobacco, from tobacco enemas, from topical application to the skin and from accidental drinking of nicotine insecticide preparations. In 1932 a florist sat down on a chair, on the seat of which a 40% free nicotine insecticide solution had been spilled. Fifteen minutes later he felt ill (vomiting, sweating, faintness and respiratory difficulty, followed by loss of consciousness and cardiac irregularity). He recovered in hospital over about 24 h. On the fourth day he was deemed well enough to leave hospital and was given his clothes, which had been kept in a paper bag. He noticed the trousers were still damp. Within 1 h of leaving hospital he had to be readmitted, suffering again from poisoning due to nicotine absorbed transdermally from his still contaminated trousers. He recovered over 3 weeks, apart from persistent ventricular extrasystoles (Faulkner J M 1933 Journal of the American Medical Association 100:1663).

24 The metabolic rate at rest accounts for about 70% of daily energy expenditure.

25 Peto R, Darby S, Deo H et al 2000 Smoking, smoking cessation and lung cancer in the UK since 1950: combination of national statistics with two case–control studies. British Medical Journal 321:323–329.

26 Smoking and Reproductive Life: The Impact of Smoking on Sexual, Reproductive and Child Health. Available at: http://www.bma.org.uk (accessed 27 October 2011).

27 Lancaster T, Stead L, Silagy C, Sowden A 2000 Effectiveness of interventions to help people to stop smoking: findings from the Cochrane Library. British Medical Journal 321:355–358.

28 Le Houezec J 2005 Why a nicotine vaccine? Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 78:453–455.

29 Roehr B 2005 Half a million Americans use methamfetamine every week. British Medical Journal 332:476.

30 In an extreme usage, a man was estimated to have taken about 40 000 tablets of ecstasy between the ages of 21 and 30 years. At maximum he took 25 pills per day for 4 years. At age 37 years, and after 7 years off the drug, he was experiencing paranoia, hallucinations, depression, severe short-term memory loss, and painful muscle rigidity around the neck and jaw. Several of these features were thought to be permanent. (Kouimtsidis C 2006 Neurological and psychopathological sequelae associated with a lifetime intake of 40 000 ecstasy tablets. Psychosomatics 47:86–87.)

31 The European Union regulations define ‘decaffeinated’ as coffee (bean) containing 0.3% or less of caffeine (normal content 1–3%).

32 The commonest pollen in the air of San Francisco, California, is said to be that of the cannabis plant, illegally cultivated.

33 When a chronic user discontinues, cannabinoids remain detectable in the urine for an average of 4 weeks and it can be as long as 11 weeks before 10 consecutive daily tests are negative (Ellis G M, Mann M A, Judson B A et al 1985 Excretion patterns of cannabinoid metabolites after last use in a group of chronic users. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 38(5):572–578).

34 Yesavage J A, Leirer V O, Denari M, Hollister L E 1985 ‘Hangover’ effects of marijuana intoxication in airline pilots. American Journal of Psychiatry 142:1325–1328.

35 Working Party Report 2005 Cannabis and Cannabis-Based Medicines: Potential Benefits and Risks to Health. Royal College of Physicians, London.

36 Van Gaal L F, Rissanen A M, Scheen A J et al 2005 Effects of the cannabinoid-1 receptor blocker rimonabant on weight reduction and cardiovascular risk factors in overweight patients: 1-year experience from the RIO-Europe study. Lancet 365:1389–1397.

37 Henquet C, Murray R, Linszen D, van Os J 2005 Prospective cohort study of cannabis use, predisposition for psychosis, and psychotic symptoms in young people. British Medical Journal 330:11–14.

38 Bass M 1970 Sudden sniffing death. Journal of the American Medical Association 212:2075.