65 Dorsal Endoscopic Rhizotomy for Chronic Nondiscogenic Axial Low Back Pain

KEY POINTS

Introduction

Traditional treatment of low back pain from an aging spine encompasses many techniques. When surgery is contemplated, diskectomy, laminectomy, and fusion are the most common surgical procedures utilized. Diskectomy, the most common surgical procedure for sciatica and back pain, may exacerbate the back pain, especially when there is concomitant spinal instability. Chronic back pain may therefore be a consequence following surgical diskectomy. Natural progression of the degenerative process also results in lumbar spondylosis, facet arthrosis, spinal stenosis, and spondylolisthesis in the time line of an aging spine, which may also be the source of pain generation. The costs of surgical procedures to correct these conditions vary widely, depending on the surgical procedures chosen and implemented by the surgeon. Fusion, the traditional procedure for back pain, is usually recommended with caution because of its surgical morbidity and high cost. Failed back surgery syndrome (FBSS), with a paucity of effective salvage procedures, then result when surgical treatment fails. One recent study by Katz1 estimated that the annual costs associated with all treatments of back pain in the United States are over $100 billion. This cost estimate does not even consider the difficult-to-calculate economic loss due to loss of productivity from disabling low back pain. Back surgeries to relieve back pain, however, continue to steadily increase in the United States, partly because of expansion of surgical techniques and implants used to facilitate fusion. Hazard2 documented an increase in these numbers from 300,413 in 1994 to 392,948 in 2000. Though the majority of these surgeries are successful in relieving back pain, a significant percentage is not. Some studies estimate that, at best, only 60% of these surgeries are successful.3,4 These data, along with the data reported in the Spine Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT),5 demonstrate that although most spine surgeries are cost-effective, even the 2-year results for degenerative spondylolisthesis, the premier indication for one-level fusion, is questioned. With good patient selection, accurate diagnostic criteria, and a low cost, a minimally invasive surgical option, addressing just the innervation of the facet-mediated pain generator, may be a viable minimally invasive procedure to be considered before the definitive surgical fusion or joint replacement option is considered.

The Yeung Endoscopic Spine Surgery (YESS) decompressive approach, described in Chapter 64, details a transforaminal endoscopic approach that utilizes a minimally invasive surgical technique enabling disc and foraminal decompression as well as ablation of painful nerves and removal of chemical mediators in the disc, annulus, and foramen. Presumed primary sensory nerves innervating the disc and facet can be ablated, and pathologic conditions causing inflammation (and, therefore, pain) are addressed. The technique, expanded to target denervation of the branches of the dorsal ramus responsible for facet mediated pain, is the subject of this chapter.

Lumbar spondylolysis, facet arthrosis, spondylolisthesis, both isthmic and degenerative, that may also be associated with spinal stenosis, are traditionally treated with open decompression, dynamic stabilization, or fusion. A recent article by Weinstein et al,5 examining the data from the SPORT trial, concluded that degenerative spondylolisthesis surgery (decompression and fusion) is not a cost-effective procedure when examined over a 2-year period. These data highlight the need to better evaluate back pain patients with more specific diagnostic procedures, such as evocative diskography, selective nerve root blocks, foraminal epidural steroids, and facet and medial branch blocks. The information obtained from these procedures in experienced hands allows the surgeon to more selectively choose who might benefit from surgical intervention. Many of the pain generators can also be addressed earlier in the disease process if surgery does not cause significant paradoxical effect on the aging spine. In this chapter we outline a technique for performing endoscopic medial, intermediate, and lateral branch rhizotomy arising from the dorsal ramus, a sensory branch from the origin of the main spinal nerve, that we have termed, dorsal endoscopic rhizotomy.

Indications and Contraindications

Ideal Indications

Patients who will most likely benefit from selective endoscopic rhizotomy include the following:

Relative Indications

Patients with Poor Indications for Dorsal Ramus Rhizotomy

Patients with lumbosacral radiculopathy whose debilitating leg pain is greater than back pain:

Patients initially benefiting from dorsal endoscopic rhizotomy, who have recrudescence of some of their back pain, may have pain from progression of vertical load forces shifting to the facets, such as progressive degenerative scoliosis. These patients will have relief for 2 to 3 years before the effect of rhizotomy fails. Spinal pain, however, may also come from multiple causes and multiple anatomic structures in the spine. Certain conditions such as anomalous nerves in the foramen may not be detectable using currently available technology, but may be visualized endoscopically. For a structure to be implicated, it needs to be shown to be a source of pain from reliable diagnostic techniques. Endoscopic examination of the foramen during foraminal surgery, discussed in Chapter 64 on foraminal surgery for painful conditions of the lumbar spine, identifies some of these nerve structures and anomalies. The known structures responsible for pain in the spine include, but are not limited to, the vertebral bodies, intervertebral discs, nerve roots, facet joints, ligaments, muscles, and sacroiliac joints. Postlaminectomy syndrome (FBSS) following operative procedures may affect these structures, and, except for recurrent disc herniation or lateral recess stenosis, may not be surgically correctable. Contraindications for facet rhizotomy are pain syndromes not involving the facet joint in some way. Neural blockade or nerve block therapy, however, is a validated procedure that, when performed properly, can implicate the facet joint as responsible for spinal pain in up to 40% of patients with low back pain.7 Patients with this condition usually have moderate to severe back pain that does not have a strong radicular component. Pain is aggravated by hyperextension of the spine, and may present with tenderness to palpation at the level of the suspected facet joint. Patient selection, therefore, depends more on the patient’s response to proper administration of medial branch blocks rather than facet injections, because the procedure targets the nerve innervating the facet joint. Although x-ray, CT scan, and MRI findings of degenerative disc disease, lumbar spondylosis, and facet arthrosis are helpful in concluding that the facet is involved in axial back pain, the success of surgical ablation of the branches of the dorsal ramus is dependent on clear interpretation and effective resolution of axial back pain from medial branch blocks. Adding low-dose steroids (methylprednisolone [Depo-Medrol]) to longer-acting anesthetic agents such as 0.5% bupivacaine provides long enough relief of axial back pain to help make a clinical decision on the projected effectiveness of endoscopic rhizotomy. Patient selection for the procedure for the prospective study begun in 2006 was indicated for patients receiving at least 50% back pain relief, but the pilot study demonstrated endoscopic rhizotomy is most successful for those reporting 80% to 90% relief of their axial back pain following a medial branch block. Contraindications are relative, since there may be limitations on the effects of nerve denervation. In patients with multiple or nonspecific pain generators such as myofascial pain syndrome, sacral iliac joint pain, or those with a soft tissue source of pain where no nerve root pathology exists, have less satisfactory results, even if there is a facet-component. Therefore, including these patients who also have facet-mediated pain may serve as relative contraindications. However, if the patient understands that the relief they get from facet rhizotomy is limited to the facet joint, then a satisfactory result can be obtained. The effect of facet denervation in the pain management literature cites pain relief lasting only 6 months to 1 year.8,9 This is because current techniques of radiofrequency lesioning may not be complete. Dorsal endoscopic rhizotomy, however, was able to attain pain relief for this time frame more effectively, because the surgeon is able to confirm adequate ablation of a visualized nerve branch or the consistent location at least of the medial branch. Patients who fail to get relief from radiofrequency ablation have been shown to get significantly more relief following dorsal endoscopic rhizotomy. These patients may be offered dorsal endoscopic rhizotomy cautiously, because we assume that failure may be due to poor patient selection rather that technique failure. An ongoing continued review of A. Yeung’s 2006 prospective pilot study (presentation made at the International Society for Minimally Invasive spine surgery in January 2007. Information not published.) reveals a majority of patients still experiencing continued relief since the inception of the study (up to 3 years). Because of multiple pain sources in patients with an aging spine, results of endoscopic rhizotomy are less predictable in patients who were only partially relieved of back pain obtained from the diagnostic blocks. Each injection should be individually evaluated for clinical efficacy. In patients with only very temporary pain relief, another trial block may be considered. Patients unable to stop taking their anticoagulants for stroke, transient ischemic attacks, and thrombophlebitis are at greater risk for surgical morbidity. These patients are operated on with caution, risking complications from bleeding at the surgical site. However, the ability to cauterize a small wound to control bleeding may make the contraindication a relative one.

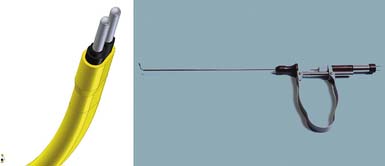

Description of the Device

A YESS (Yeung Endoscopic Spine System) rhizotomy endoscope was developed with the Richard Wolf Surgical Instrument Company (Vernon Hills, Ill.) specifically for dorsal ramus rhizotomy. The length of the scope is designed to allow the endoscope to rest on the fluid adapter with a focal length that will keep the transverse process and the nerves in focus (Figure 65-2). The endoscope has two cannula configurations, a standard round cannula with a flat opening and a cannula with a beveled opening to allow flexible curved bipolar radiofrequency electrodes and side-firing lasers to exit the wall of the cannula for tissue coagulation and resection (Figure 65-3). Straight and side-firing lasers, in addition to two types of radiofrequency electrodes, are recommended because it is a more aggressive surgical tool for stripping the periosteum and soft tissue envelope that may shield the medial branch.

Background of Scientific Testing and Clinical Outcomes

Radiofrequency has been extensively used for ablation of the medial branch in treating facet joint pain for years. It has been reported that most patients only benefited from short term relief of pain.8,9 It is also observed that recurrent axial pain from the same lesioned facet may be due to reinnervation by regrowth of nerves. For this assumption, repeat radiofrequency for recurrence is common. Finding the exact location of the medial branch, however, is not only essential to ablate the nerve, but in our study, the medial branch was sometimes found to be buried in a periosteal tunnel up to several millimeters thick. Blind, even perfectly placed, thin wire electrodes may not be able to adequately ablate the nerve. Efforts have been made to improve the radiofrequency technique by needle position, making multiple lesions and using larger needles.10 To continue this effort, the senior author (ATY) embarked on an endoscopic surgical technique in 2005 using the FDA-approved Vertebris 3.1-mm spine endoscope spine system for foraminal lumbar surgery. In the YESS system, bipolar radiofrequency flex probe and Ho:YAG laser are important surgical tools for tissue ablation and thermomodulation. It has been reported that percutaneous laser medial branch rhizotomy provided better and longer-lasting results than radiofrequency lesioning,8,9 and this reasoning is confirmed by using the same tools in selective endoscopic rhizotomy. Derby and Lee10 reported in 2006 that a more aggressive ablative process gives better results than traditional percutaneous techniques utilizing two needle electrodes during lumbar facet rhizotomy in an experimental model. The literature also supports multiple ablations with radiofrequency because it provided better results than a single lesion. A prospective study was initiated by the senior author in March 2006 before Dr. Linqiu Zhou reported his work on cryotherapy for dorsal ramus syndrome at the 19th International Intradiscal Therapy Meeting in April 2006. Dr Zhou was involved in the Chinese study of over 2630 patients that utilized a cryotherapy technique targeting the dorsal ramus to relieve pain from chronic muscle spasm, and upper lumbar back pain. The paper presented by Dr. Zhou and colleagues, titled “The Spinal Dorsal Ramus and Low Back Pain,” presented evidence that anatomic dissections of the dorsal ramus at L1 and L2 extended two to three segmental levels below L2.11

A prospective, nonrandomized study was initiated by the senior author to determine whether the dorsal ramus, particularly the medial branch, could be visualized endoscopically, and whether endoscopic rhizotomy of the medial branch and visualized intermediate and lateral branches of the dorsal ramus would produce better results than conventional rhizotomy techniques. The pilot study of 50 consecutive patients was initiated in March, 2006, and was first reported at the 25th International Jubilee Course on Percutaneus Endoscopic Spine Surgery and Complementary Techniques at Zurich, Switzerland in January, 2007.6 Inclusion criteria were lumbar degenerative conditions that resulted in facet pain from the aging spine or postoperative facet-mediated pain (Table 65-1). We primarily targeted the medial branch in the osseous tunnel with an endoscope and attempted to ablate it under visual control. This resulted in excellent axial pain relief in the vast majority of patients receiving endoscopic rhizotomy. There were no complications. When the nerve branch was traced to the dorsal ramus, it resulted in fenestration of the intertransverse ligament, bleeding, and painful feedback from the patient during the ablation process. Twitching muscles could also be felt by the surgeon. Temporary ache and mild dysesthesia were reported by the patients, but no patient was worse. Ultimately, 90% (45/50) of the patients still had relief at 6 months follow-up. Only five patients had recurrence of their back pain at 6 months. Aggressive ablation of the dorsal ramus or inadvertent penetration of the probe and cannula deep to the intertransverse ligament sometimes caused bleeding and temporary dysesthesia, This led to the use of indigo carmine dye to help guide the surgeon to stay dorsal to the ligament in pursuing the nerve. We therefore conclude that ablation of the dorsal ramus is not needed, even if potentially more effective in relieving back pain, because it may cause unacceptable unforeseen complications by ablation near the dorsal root ganglion. VAS and Oswestry scores were tabulated. VAS decreased from 6.2 to 2.5 and Oswestry from 48 to 28; 90% of patients had continued improvement at 6 months follow-up (Table 65-2). The extended study continues, and recent review of patient data by an independent reviewer and co-author (Y. Zheng) further confirmed the previous study results. In carefully selected ideal patients, satisfactory results were achieved in more than 90% patients without complications. These encouraging data and satisfactory feedback from patients motivated the authors to introduce this new minimally invasive endoscopic surgical technique.

TABLE 65-1 Inclusion Criteria of Pilot Study on Selective Endoscopic Rhizotomy

| Pilot Study Inclusion Criteria: Endoscopic Medial Branch and Dorsal Ramus Rhizotomy |

|---|

TABLE 65-2 Results of Prospective Nonrandomized Study

| Prospective Non randomized Pilot Study |

|---|

| Method: Endoscopic medial branch And D.R.Rhizotomy |

| Preliminary Early Results |

Operative Technique

Procedure

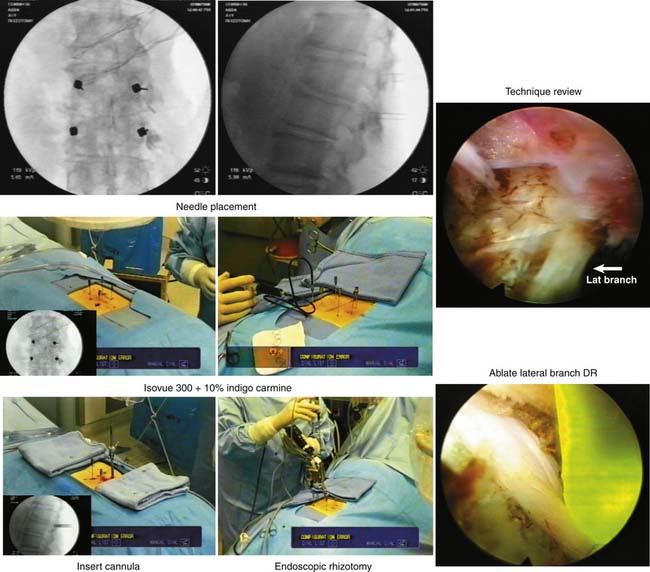

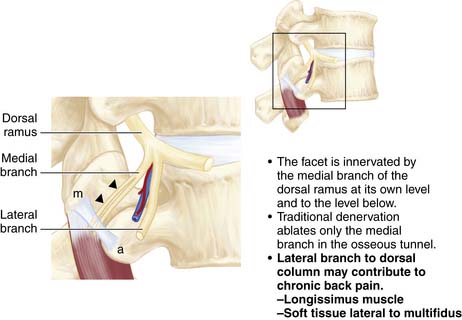

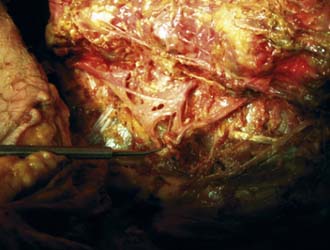

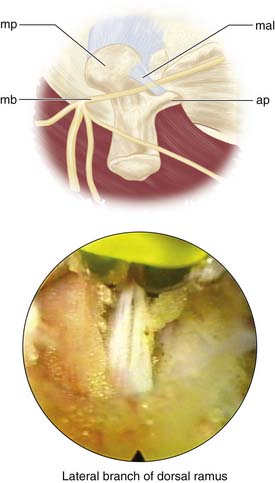

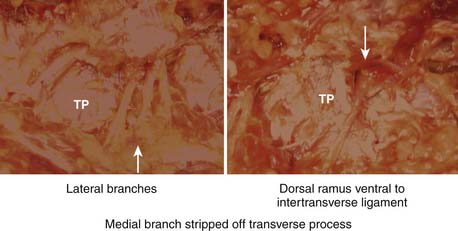

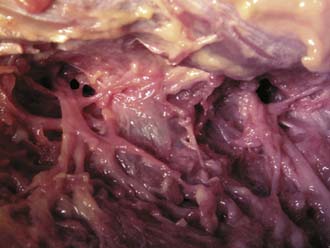

The procedure begins with needles placed on the transverse process just lateral to the facet in the muscle interval between the multifidus and longissimus muscle (Wiltse’s paramedian approach). Isovue 300, mixed with 10% indigo carmine dye, is injected into the interval to help the surgeon identify the tissue plane endoscopically. Indigo carmine dye is used to mark the tissue planes and the level of the transverse process dorsal to the intertransverse ligament. At times dye can be seen leaking to the facet joint capsule or to the foramen, at times even outlining the location of the dorsal ramus if there is a breach of the foraminal ligament leading to the foramen. The endoscope is then inserted through the cannula and docked on the transverse process (Figure 65-4). The medial branch of the dorsal ramus is first targeted (Figure 65-5). It is not always visualized because the nerve is protected by a soft tissue envelope. However, when the nerve is identified crossing the transverse process, it is transected under direct vision, as is the lateral branch. A modification of the technique begins with wagging the blunt obturator to develop the tissue plane between the multifidus and longissimus muscle. This facilitates visualization of the lateral branch of the dorsal ramus, cephalad to the edge of the transverse process (Figure 65-6). If the nerve is not identified, all the soft tissues are stripped to the periosteum of the transverse process adjacent to the lateral facet, especially to the cephalad edge of the transverse process. In the first 50 patients of the prospective study, the nerves at the base of the transverse process were mainly targeted, while looking primarily for the medial branch. The intermediate and lateral branch was targeted when visualized. With the wagging maneuver, the intermediate and lateral branch was visualized more easily. After 100 patients, continued surgical experience and greater surgeon experience allowed for more aggressive dissection along the tissue plane between the multifidus and longissimus muscles to actively look for multiple lateral branches to ablate, sometimes following the branches to the dorsal ramus. Care, however, is taken to stay dorsal to the intertransverse ligament to avoid irritation of the exiting spinal nerve and the dorsal root ganglion in the foramen. Our cadaver dissections provided even more anatomic information on the complexity of facet innervation, especially from L3 cephalad (Figure 65-7). This finding, plus some anatomic dissections with demonstrating caudal connections of the dorsal ramus with segments below (Figure 65-8), provides evidence that rhizotomies of the dorsal ramus above the level of imaging involvement may have a role in the treatment of axial facet mediated pain. We do not, however, recommend routine ablation of the dorsal ramus because it is very benign to ablate the branches of the dorsal ramus at the involved spinal segment, and the risk of neuroma and spinal nerve injury is lessened significantly.

FIGURE 65-6 Location of the lateral branch of the dorsal ramus in relation to the transverse process.

FIGURE 65-7 Cadaver dissection of the dorsal ramus and its branches in relation to the transverse process.

The medial branch of the dorsal ramus was more difficult to identify than the lateral or intermediate branches because it may be buried in thick periosteum or capsular tissue, but ablation of soft tissue to cortical bone assured ablation of the medial branch. The Ho:YAG laser (Trimedyne, Inc., Santa Ana, CA) was found to be the most effective surgical tool for ablation through thick collagenous tissue. If the procedure is modified to develop the plane between the multifidus and longissimus muscles, much like a dissection using Wiltse’s approach to the transverse process for pedicle screw placement. It is easier to visualize the intermediate and lateral branches. The literature contains illustrations of the anatomy of the dorsal ramus and its branches at the transverse process (see Figure 65-4).

Postoperative Care

The patient is sent home if his insurance allows endoscopic rhizotomy as an outpatient procedure; otherwise the surgery is performed in a hospital and the patient is admitted for overnight observation until the patient opts to go home. There is no postoperative treatment plan specific to rhizotomy. The patient is returned to his or her normal or desired activity level.

Complications and Avoidance

Rarely, transient dysesthesia may result, especially when there was inadvertent penetration of the intertransverse ligament or if the patient felt pain during the ablative procedure. Ablation of the lateral branch may cause the muscles to twitch, but the patient should have no pain. Staying dorsal to the intertransverse ligament avoids the possibility of exiting and foraminal nerve injury. The use of indigo carmine dye helps the surgeon stay dorsal to the foramen. Avoiding ablation of the dorsal ramus may remove risk of neuroma formation or irritation of anomalous nerves such as furcal nerves and autonomic nerves in the foramen described in Chapter 64

Conclusions and Discussion

Endoscopic ablation of the medial branches, along with a selected lateral branch of the dorsal ramus, is effective in relief of chronic axial back pain from facet joint and may decrease the need and consideration of fusion as a surgical means of relieving chronic axial back pain (Figure 65-9, Box 65-1). It is certainly more cost-effective in the short term compared to fusion. A large-scale and long-term follow-up is needed to observe whether the technique can decrease the trend toward more fusion procedures in managing axial back pain in the aging spine. Endoscopic rhizotomy offers a bridge for treating many spinal ailments in patients who might not fare well with large open surgeries yet need something more than conventional pain management. To understand selective endoscopic rhizotomy, the detailed surgical anatomy of the dorsal lumbar rami and its significance for dorsal rhizotomy is reviewed.

Box 65-1 ENDOSCOPIC RHIZOTOMY

Patients who failed RFL have had successful results with endoscopic rhizotomy.

The effect may be even more lasting when laser rhizotomy is incorporated for lesioning.

Anatomy of the Lumbar Dorsal Ramus

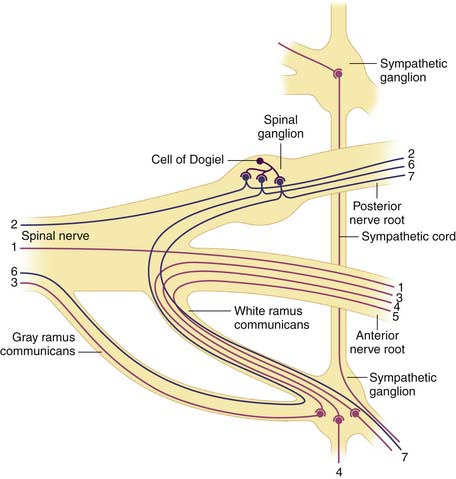

There are five pairs of lumbar spinal nerves (Figure 65-10). Centrally, the spinal nerve consists of ventral and dorsal roots. The ventral root comes from the anterior horn of the spinal cord and the dorsal root comes from the posterior horn of the spinal cord. The dorsal root has a dorsal ganglion after leaving the spinal cord and before joining the ventral root. The ganglion contains the cell bodies of the sensory fibers in the dorsal root. The ganglion lies within the dural sleeve of the nerve root and occupies the upper and medial part of the intervertebral foramen. The ventral and dorsal roots join together laterally become the spinal nerve in the intervertebral foramen. After leaving the spinal canal just outside the foramen, the spinal nerve divides into a larger ventral ramus innervating the lower extremities and a smaller dorsal ramus innervating the zygapophyseal joint, back muscles, and ligaments.

L1 to L4 Dorsal Rami

Bogduk described the lumbar dorsal rami in detail from his anatomical dissection of cadavers.10 (Bogduk 1980) The L1 to L4 dorsal rami project at almost a right angle to the spinal nerve. The main stem is only about 5 mm long. It runs dorsocaudally through the intertransverse space, deep to the intertransversarii mediales. They are divided into three branches: medial, lateral, and intermediate.

L5 Dorsal Ramus

The L5 dorsal ramus is longer than the L1-L4 dorsal rami. It courses the superior border of the ala of the sacrum, lying in the groove formed by the junction of the ala and the superior articular process of the sacrum. It divides into medial and intermediate branches, lacking a lateral branch. The medial branch curves medially around the caudal aspect of the lumbosacral facet joint and ends in the multifidus muscles. The intermediate branch innervates the longissimus thoracis and communicates with the S1 dorsal ramus. Ablation of the branches of the dorsal ramus, with its complex innervation, may provide axial back pain relief beyond the level surgically ablated. Care is taken when the dorsal ramus is ablated because partial ablation of a large nerve may result in dysesthesia or the formation of a neuroma. No patient, however, considered themselves as worse, even if the procedure did not provide the anticipated or desired pain relief.

1. Katz J.N. Lumbar disc disorders and low-back pain: socioeconomic factors and consequences. J. Bone Joint. Surg. Am.. 2006;88(Suppl 2):21-24.

2. Hazard R.G. Failed back surgery syndrome: surgical and nonsurgical approaches. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res.. 2006;443:228-232.

3. Martin B.I., Mirza S.K., Comstock B.A., et al. Reoperation rates following lumbar spine surgery and the influence of spinal fusion procedures. Spine. 2007;32(3):382-387.

4. Weir B.K., Jacobs G.A. Reoperation rate following lumbar discectomy. An analysis of 662 lumbar discectomies. Spine. 1980;5(4):366-370.

5. Weinstein J.N., Tosteson T.D., Lurie J.D., An Tosteson, Hanscom B., Skinner J.S., et al. Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disc herniation: the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT): a randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2441-2450.

6. A.T. Yeung, Endoscopic medial branch and dorsal ramus rhizotomy for chronic axial back pain: a pilot study, International 25th Jubilee Course on Percutaneus Endoscopic Spine Surgery and Complementary Techniques. Zurich, Switzerland. January 24-25, 2007.

7. Datta S., Lee M., Falco F.J., Bryce D.A., Hayek S.M. Systematic assessment of diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic utility of lumbar facet joint interventions. Pain Physician.. 2009;12(2):437-460.

8. Iwatsuki K., Yoshimine T., Awazu K. Alternative denervation using laser irradiation in lumbar facet syndrome. Lasers Surg. Med.. 2007;39(3):225-229.

9. Kantha Sri. Lumbar facet joint denervation by laser thermo-coagulation. 18th International Intradiscal Therapy Society Meeting May 25-28, 2005, San Diego, CA.

10. Derby R., Lee C.H. The efficacy of a two needle electrode technique in percutaneous radiofrequency rhizotomy: An investigational laboratory study in an animal model. Pain Physician.. 2006;9(3):207-213.

11. Linqiu Zhou, Carson D. Schneck, Zhenhai Shao. The spinal dorsal ramus and low back pain. Presented at the 19th Annual Meeting of International Intradiscal Therapy Society. Phoenix, AZ. Apr. 5-9, 2006.

12. Bogduk N., Wilson A.S., Tynan W. The human lumbar dorsal rami. J. Anat.. 1982;134:383-397.