213 Documentation

• The emergency department (ED) chart must be adequate to support billing and accurate to prevent claims of fraud against the emergency physician.

• Most reimbursement comes from the five levels of the evaluation and management codes and is dependent on a combination of historical and physical examination data, medical decision making, and diagnostic assignments.

• Billing for critical care requires more than 30 minutes of physician attention to a patient and obviates the level-specific evaluation and management charting requirements.

• Billing for observation requires separate documentation in the ED chart.

• The emergency physician is legally accountable for claims based on the ED chart, including the potential for audits of electronic medical records by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and criminal penalties in cases of upcoding, such as assumption coding.

Introduction

Documentation in the emergency department (ED) medical record serves three basic functions:

1. To provide a detailed record of a patient’s medical conditions and treatments

2. To minimize the medical liability risk of emergency physicians (EPs) by documenting the thought process behind treatment plans

3. To support the charges billed to the patient by clearly substantiating the services rendered

Current Procedural Terminology Codes

A CPT code is a unique five-digit code that represents a service in contemporary medical practice that is being performed by physicians.1 Some common examples of emergency procedures and physician fees are listed in Table 213.1. The AMA Relative Value Update Committee assigns a relative value unit (RVU) to the code to reflect the complexity of the service relative to other physician services. The Resource-Based Relative Value Scale ranks services according to three factors: (1) the relative work of the physician, (2) the cost of performing the service, and (3) the risk involved in the service to both the patient and the provider. Each of these factors is assigned a numerical value, which when added together gives a total RVU for the service. This RVU is then multiplied by a geographically adjusted monetary conversion factor to arrive at an actual fee for the services provided (see Table 213.1).

Table 213.1 Sample Fee Schedule for Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Massachusetts Emergency Medicine Procedure and Physician Fees, Effective September 1, 2004

| PROCEDURE CODE | PROCEDURE | FEE |

|---|---|---|

| 10060 | Drainage of skin abscess | $102.98 |

| 10120 | Removal of foreign body | $78.37 |

| 12001 | Repair of superficial wound(s) | $104.75 |

| 12032 | Layer closure of wound(s) | $208.87 |

| 16020 | Treatment of burn(s) | $68.77 |

| 23650 | Shoulder dislocation | $308.73 |

| 29125 | Application of forearm splint | $48.75 |

| 29130 | Application of finger splint | $32.58 |

| 30901 | Control of nosebleed | $73.45 |

| 31500 | Insertion of emergency airway | $135.95 |

| 62270 | Spinal fluid tap, diagnostic | $76.92 |

| 69210 | Removal of impacted earwax | $40.66 |

| 99235 | Observation/hospital same date | $220.62 |

| 99236 | Observation/hospital same date | $274.84 |

| 99281 | ED visit (level 1) | $24.61 |

| 99282 | ED visit (level 2) | $41.29 |

| 99283 | ED visit (level 3) | $91.68 |

| 99284 | ED visit (level 4) | $142.32 |

| 99285 | ED visit (level 5) | $222.63 |

| 99291 | Critical care, first hour | $245.68 |

| 99292 | Critical care, additional 30 min | $122.89 |

ED, Emergency department.

Evaluation and Management

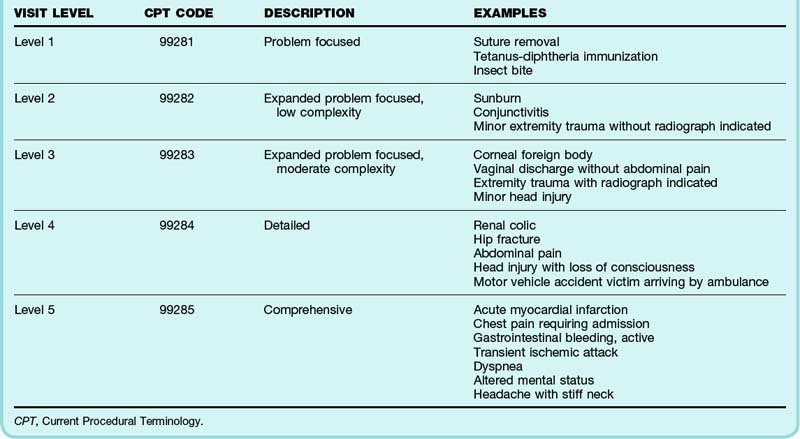

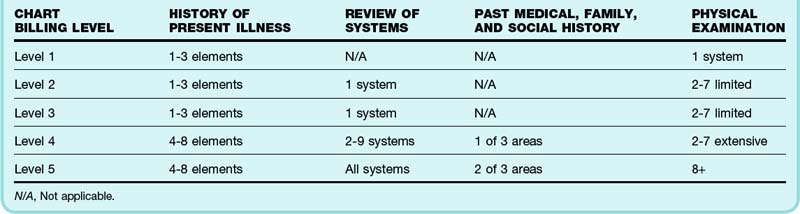

The evaluation and management (E&M) codes are five CPT codes (see Table 213.1) that account for approximately 85% of all EP reimbursement. These five codes categorize the complexity of the encounter. Coders (and hence payers) rely on the documentation of historical information, physical examination, and medical decision making (MDM) to determine the complexity of the visit. The last digit of each CPT code is used to denote the “level” of service (Table 213.2). Services provided between the hours of 10 PM and 8 AM may be coded with an additional code, 99053.2 Each progressive level of service requires incrementally more documentation to support the level of coding. The EP must be sure to document an adequate history of the present illness (HPI), review of systems (ROS), and past medical, family, and social history (PMFSHx) to support each level of the chart. This requirement increases substantially for level 4 and 5 charts (Tables 213.2A and 213.2B). The HPI should include a variety of descriptors of the chief complaint, including the relevant location, quality, severity, timing, context, and associated symptoms. The ROS and PMFSHx can be recorded by ancillary staff (resident, nurse practitioner, and others) or on a form completed by the patient but must have a notation supplementing or confirming that this information has been reviewed by the attending physician.

See Table 213.3A, Charting Requirements for Charts by Level, and Table 213.3B, Emergency Department Observation Codes and Descriptions, online at www.expertconsult.com

Certain statements commonly used in medical documentation deserve specific mention. The PMFSHx should contain specific historical information obtained from the interview. Truncating the ROS with “all other systems negative” is adequate to meet documentation requirements for a level 5 visit; however, it should be used cautiously. When used indiscriminately in low-acuity patients, it may raise concern for upcoding and subject the EP to an audit.3 The designation “unable to obtain secondary to acuity or mental status” is appropriate for patients from whom no history can be obtained. EPs should document the specific clinical condition that prevents them from obtaining the history, as well as the specific source of the historical information obtained, such as nursing home records, family members, or electronic records.

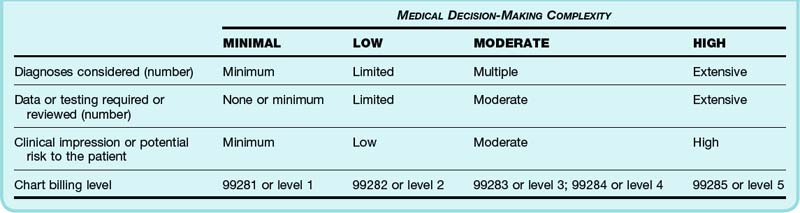

MDM is the most complex and least clinically intuitive. MDM should capture in text the complexity of the decision-making process and reflect the intellectual workload of the EP. It should include at minimum two of the following three elements: the number of possible diagnoses or treatments, the tests or records reviewed, and the potential risk to the patient, including complications of treatment or possible morbidity or mortality (Table 213.4). When applicable, EPs should also list all major comorbid conditions affecting their decision making, consultations, and discussions with primary care providers.

In assigning diagnoses, EPs should list all diagnoses applicable to the patient’s current situation, including abnormal vital signs.4 For example, a hypotensive patient with diverticulitis and fever should have the diagnotic assignments of “hypotension,” “diverticulitis,” and “pyrexia.” Language that does not connote a specific diagnosis, such as “rule out,” “probable,” “motor vehicle accident,” “possible,” “chronic,” or “mild,” should be avoided. Including a breadth of diagnoses to paint a more thorough and accurate clinical picture of the clinical workload involved will maximize billing.5

Critical Care

Critical care (E&M code 99291) is the E&M of an unstable, critically ill, or injured patient for which the EP’s constant cognitive attendance is required.1 Many intensive care unit admissions qualify for critical care billing because they involve “a critical illness or injury that acutely impairs one or more vital organ systems such that there is a high probability of imminent or life threatening deterioration in the patient’s condition.”6 Common clinical conditions that should prompt consideration of critical care include sepsis, abdominal aortic aneurysm, ruptured ectopic pregnancy, trauma, stroke, subarachnoid hemorrhage, atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response, acute coronary syndrome, severe asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring bilevel positive airway pressure, diabetic ketoacidosis, and hyperkalemia. The first 30 minutes, up until 74 minutes of care, is billed with this code, after which additional increments of 30 minutes (code 99292) may be billed. The physician must be engaged in work directly related to the individual patient’s care. Because of the implied severity of the patient’s condition, none of the history or physical examination requirements apply to qualify for critical care billing. Certain procedures associated with critically ill patients may be “bundled” with the critical care payment and thus are not billable separately. Such procedures include arterial blood gas, electrocardiogram (ECG), chest radiograph, and pulse oximetry interpretation; gastric intubation; temporary transvenous pacing; ventilator management; vascular access; cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR); and defibrillation.

Billing Compliance

Accuracy is essential to avoid issues of fraud and abuse. All EPs are individually responsible and accountable for correct processing of the claims associated with their charts. It is incumbent on EPs to document the visit accurately without underrepresenting or overrepresenting the encounter’s complexity.4,5 Using electronic macros with identical documentation of HPI and MDM across different patient encounters can be a red flag to billing auditors.7 Cutting and pasting text verbatim is strongly discouraged by the CMS. Ancillary providers and scribes may be used to document information on the chart but must have their own electronic signature.

Recovery Audit Contractors (RACs) are auditing groups hired by the CMS to review the documentation supporting claims to detect and correct payments that are not supported by adequate documentation of a clinical encounter.8 RACs review claims on a postpayment basis by using two types of review, automated (no medical record needed) or complex (complete medical record required). A RAC employs a staff consisting of nurses, therapists, certified coders, and a physician to review reimbursements with the goals of lowering inappropriate reimbursement rates by the CMS, providing public accountability of health care expenditures, and providing feedback to EPs submitting claims that do not comply with Medicare reimbursement rules.

Documentation is perhaps most important when it comes to protecting EPs from claims of fraud in providing care. Procedures or services that are billed for and not documented, regardless of whether they occurred, are considered fraudulent and are subject to criminal penalties. Assumption coding is defined as billing at a higher level than what the chart supports. For example, a patient with chest pain and changes on the ECG who is admitted on intravenous heparin qualifies for a level 5 encounter. However, if the EP seeing this patient documents only a four-element HPI, 5 physical examination points, moderate-complexity MDM, and “rule out myocardial infarction” as the diagnosis, the evidence provided by this chart is inadequate to support billing above level 4. If this chart were reviewed, the EP would be liable for filing a fraudulent claim. To protect physicians from such pitfalls, physician groups or hospitals should have compliance review committees in place to review charts in a systematic fashion to ensure that EP documentation and chart coding are appropriate and consistent for the patient services rendered.6

1 Current procedural terminology 2004 standard edition. St. louis: AMA Press, 2005.

2 Granovsky MA, Parker RB. 2006 CPT and ICD 9 changes impact emergency medicine coding and reimbursement. ACEP EM Today. Dec 19, 2005.

3 CPT Changes 2007: an insider’s view. St. louis: American Medical Association, 2007.

4 Siff JE. Fundamentals of physician billing, coding, and compliance. In: Aghababian, ed. Essentials of emergency medicine. Sudbury, Mass: Jones & Bartlett; 2006:1002–1003.

5 Eitel D. Advanced business life support course. York, Pa: York Hospital; 1998.

6 American Medical Association. CPT: current procedural terminology. Chicago: AMA; 2011.

7 Granovsky MA, Thomas T. MACEP coding and reimbursement conference. Massachusetts Medical Society; November 19, 2010.

8 www.cms.gov/RAC. Accessed November 28, 2010

Procedural Billing

Wound care and closure are of particular relevance to EPs. Adhesive closure of lacerations is billed at a lower “G” code RVU rate unless deep absorbable sutures are also placed, which allows standard laceration billing (see Table 213.1). Wounds requiring decontamination or débridement may be considered intermediate-complexity laceration repairs even if only a single-layer closure is required. Burn care can be billed for burns requiring the application of topical ointment and dressing. CPR may be billed separately but not contemporaneously with critical care time. Critical care billing would start only after completion of the course of CPR. Intubation currently continues to be a single CPT code and does not account for more advanced or resource-intensive methods such as fiberoptic modalities.

Observation Care

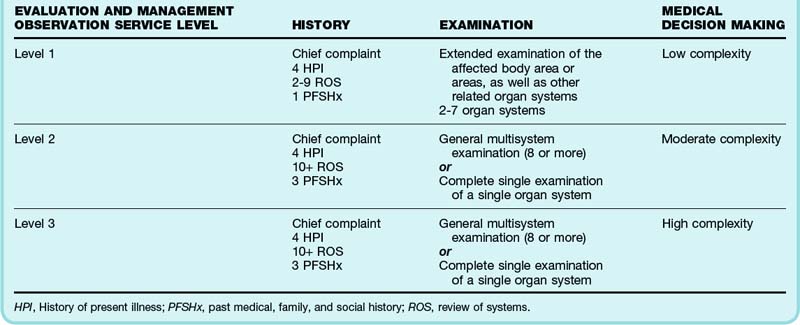

Observation care billing codes exist for E&M services provided to patients designated or admitted to “observation status” in an ED or ED observation unit. These services are separate from the ED visit and hence require separate documentation, including an admission order, admission note referencing the ED record, progress notes, a discharge note, and a discharge order on release of the patient. Observation charts may be billed at levels 1 to 3 based on the complexity of the history, physical examination, and MDM, similar to ED chart billing (see Table 213.3B).6 Physician extenders such as nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) may be used to staff an observation unit. Although PAs require direct attending oversight, NPs may operate independently; however, Medicare reimburses independent NP services at only 85% of the physician rate. To qualify for full reimbursement as a “shared visit,” the EP must document the history, physical examination, and MDM and make note of review of PA or NP documentation.

Hospital Billing and Capturable Revenue

The payer mix of an ED is the variety of insurance coverage for a patient population that determines the cash flow for a physician group.6 After the ED chart has been coded and billed to an insurer, the return on the dollar amount, or capturable billable revenue, is approximately 40%.6 Payment is sent out approximately 40 to 100 days after the bill is submitted, thus causing a significant delay in reimbursement for the department or physician group. This cycle time makes timely completion of ED charts essential to ensuring cash flow. Metrics such as chart completion by the provider, distribution of E&M visits per provider, RVUs per provider, and charges or collections per payor over time are critical to ensure the financial health of a department.