Dizziness and Vertigo (Case 57)

Lana Zhovtis Ryerson MD and Stephen Krieger MD

Case: A 34-year-old woman presents to the ED with dizziness. She states that 2 days ago she began to feel a “spinning sensation” and was walking around “as though she were drunk.” These symptoms worsened the day before admission, when she developed nausea and vomiting and had increasing difficulty walking. She has no significant past medical history. On exam she has beating nystagmus in all directions of gaze, worse when looking to the right. She has a slightly flattened right nasolabial fold. She has full strength and an intact sensory exam, but on coordination testing she has significant postural instability, as well as dysmetria in the right arm. She is unable to tandem walk, falling to the side.

Differential Diagnosis

|

Vertigo |

Dizziness/presyncope/light-headedness |

|

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) |

Orthostatic hypotension |

|

Acute labyrinthitis/vestibular neuritis |

Cardiac arrhythmia |

|

Meniere disease |

Vasovagal disorder |

|

Cerebellar infarction or hemorrhage |

Intoxication/medication side effects |

|

Perilymphatic fistula |

Anxiety |

Speaking Intelligently

Although prevalence studies vary in their definition of the symptom, dizziness is common in all age groups, and its prevalence increases modestly with age. While peripheral vestibular etiologies are among the most common causes, as many as 25% of patients with risk factors for stroke who present to the emergency medical setting with the combination of vertigo, nystagmus, and postural instability may have a stroke affecting the cerebellum.

For most patients the symptom of dizziness resolves spontaneously, but an important minority of patients can develop chronic, disabling symptoms. Patients with chronic dizziness may benefit from an approach aimed at identifying and managing treatable conditions, whether etiologic or contributory. This approach may include correcting visual impairment, improving muscle strength, adjusting medication regimens, identifying and treating psychological comorbidities such as anxiety and depression, and instructing patients on vestibular exercises.

PATIENT CARE

Clinical Thinking

• Vertigo is an illusory sensation of motion of either oneself or one’s surroundings.

History

When evaluating a complaint of dizziness to establish if there is frank vertigo or presyncope, questions to consider include the following:

• Is there a true sensation of movement or spinning?

• Is there a feeling of faintness and light-headedness?

• Are there vague, persistent feelings of imbalance?

• What are the associated characteristics?

• Nausea/vomiting may accompany vertigo.

• The sensation of warmth, diaphoresis, and visual blurring may indicate presyncope.

• Palpitations, dyspnea, or chest discomfort can indicate a cardiac cause.

• What is the duration of the episodes, and what are any exacerbating factors (e.g., head movement)?

• Has syncope ever occurred during an episode?

• Do episodes occur only when the patient is upright, or do they occur in other positions?

Physical Examination

|

Feature of Nystagmus |

Peripheral (Labyrinth or Nerve) |

Central (Brainstem or Cerebellum) |

|

Latency of nystagmus |

3–40 sec |

None: immediate vertigo and nystagmus |

|

Fatigability of nystagmus |

Yes |

No |

|

Direction of nystagmus |

Unidirectional, often rotatory |

Can be bidirectional, unidirectional, or vertical |

|

Visual fixation |

Inhibits nystagmus and vertigo |

No inhibition |

|

Intensity of vertigo |

Severe |

Mild |

|

Tinnitus and/or hearing loss |

Often present |

Usually absent |

|

Associated CNS abnormalities |

None |

Extremely common (e.g., diplopia, hiccups, cranial neuropathies, dysarthria) |

|

Common causes |

BPPV, vestibular neuritis, labyrinthitis, Meniere disease |

Infarction, hemorrhage, multiple sclerosis, neoplasm |

Tests for Consideration

|

$11, $15, $185, $85 |

| Clinical Entities | Medical Knowledge |

|

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo |

|

|

Pφ |

Otoliths, or calcium carbonate crystals, become dislodged from the utricle, one of the gravity-sensitive structures in the inner ear, and then migrate to the posterior semicircular canal, which is the most gravity-dependent structure in the vestibular labyrinths. |

|

TP |

Classically, patients describe a brief spinning sensation brought on when turning in bed or tilting the head backward to look up or down. Each episode of vertigo lasts only 10–20 seconds. The initial onset of vertigo is often associated with nausea, with or without vomiting. The dizziness may be quite severe, so as to halt all activity during its duration. |

|

Dx |

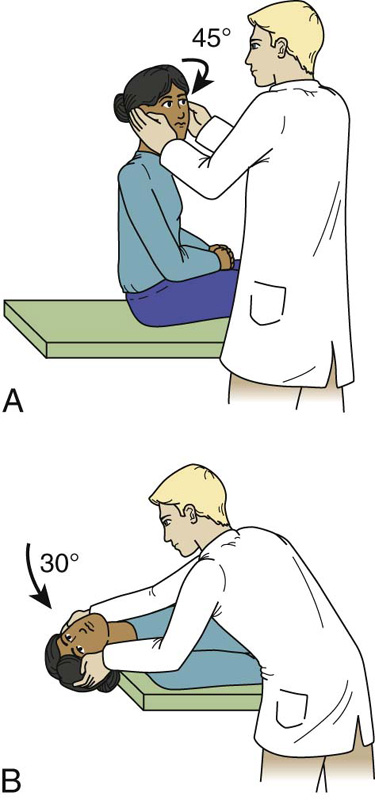

The diagnosis is generally made by eliciting the history of the episode, characterized by brief episodes of vertigo provoked by certain changes in head position such as rolling over in bed, bending over, and looking upward. The diagnosis can be confirmed with the Dix-Hallpike maneuver, for which the diagnostic criteria consist of typically rotatory nystagmus with the upper pole of the eye beating toward the dependent ear. The nystagmus typically begins after a latency of several seconds and is associated with a sensation of rotational vertigo. After the patient returns to the seated position, nystagmus is again observed, but the direction of nystagmus is reversed. |

|

The treatment currently recommended is the bedside canalith repositioning procedure (CRP), also known as the Epley maneuver. The purpose of the maneuver is to relocate free-floating debris from the posterior semicircular canal into the vestibule of the vestibular labyrinth, where it presumably adheres. The debris can be moved within the labyrinth noninvasively through a sequence of head orientations with respect to gravity. |

|

|

Vestibular Neuritis |

|

|

Pφ |

Although the pathophysiology is unclear, the condition is thought to result from a selective inflammation of the vestibular nerve and is presumably of viral origin. |

|

TP |

Vestibular neuritis presents as rapid onset of severe, persistent vertigo, nausea, vomiting, and gait instability. Physical exam findings are consistent with an acute peripheral vestibular imbalance: spontaneous vestibular nystagmus and gait instability without a loss of the ability to ambulate. In pure vestibular neuritis, auditory function is preserved; when this syndrome is combined with unilateral hearing loss, it is called labyrinthitis. |

|

Dx |

The diagnosis is based on the ability to clinically differentiate between peripheral and central causes of acute prolonged vertigo. ENG, if available, can document the unilateral vestibular loss. |

|

Tx |

There is no established treatment for vestibular neuritis. Symptomatic therapy is typically used, with the main classes of drugs including antihistamines (meclizine, dimenhydrinate, promethazine), anticholinergic agents, antidopaminergic agents, and GABAergic agents (diazepam, clonazepam). These drugs do not eliminate but rather reduce the severity of vertiginous symptoms. |

|

Meniere Disease |

|

|

Pφ |

The disease is thought to be related to an increase in the volume of endolymph in the labyrinths (endolymphatic hydrops). The hydrops causes hearing loss by a direct effect on the sensory outer hair cells of the cochlea, but the sudden spells of vertigo are less well understood. Some cases appear to be related to mutations in the cochlin gene on chromosome 14q12–q13, with the disease showing genetic anticipation (i.e., becomes apparent at on earlier age as it is passed on to the next generation). |

|

Patients present with recurring episodes of spontaneous episodic vertigo lasting for minutes to hours and usually associated with unilateral tinnitus, hearing loss, and a sensation of ear fullness. Acute attacks are characterized by severe vertigo, nausea, vomiting, and disabling imbalance. The attacks recur at intervals ranging from weeks to years. |

|

|

Dx |

The diagnosis is made by obtaining the history of episodic vertigo associated with hearing loss and tinnitus, with family history helping to confirm the diagnosis. A low-frequency sensorineural hearing loss on audiometry and a unilateral reduced vestibular response on ENG help confirm the diagnosis. |

|

Tx |

Diuretics and salt restriction are directed to reducing possible hydrops. Symptomatic relief may be obtained during acute attacks with drugs similar to those used for vestibular neuritis. In persistent, disabling, drug-resistant cases, surgical procedures such as endolymphatic shunting, labyrinthectomy, and vestibular nerve section can be helpful. |

|

Cerebellar/Brainstem Infarct or Hemorrhage |

|

|

Pφ |

The blood supply to the peripheral vestibular labyrinth and vestibular nerve, as well as the brainstem vestibular area and cerebellum, comes from the vertebrobasilar arterial system. Occlusion of one or more of the posterior circulation arteries due to embolism or atherosclerotic stenosis can produce cerebellar or brainstem vascular events. |

|

TP |

Abrupt onset, history of TIAs, vascular disease, or significant other risk factors for stroke, usually associated with other neurologic symptoms, are diagnostic. |

|

Dx |

On exam, spontaneous central-type nystagmus is seen with other associated signs of the lateral brainstem including Horner syndrome, facial numbness and weakness, hemiataxia, and dysarthria. MRI of brain shows infarction or hemorrhage in the medulla, pons, or cerebellum. Audiography may show ipsilateral hearing loss if the anterior cerebellar artery is involved. |

|

Patients with acute ischemic strokes may be offered IV tPA, intra-arterial tPA, or other clot-retrieving procedures depending on the institution and the time of onset of symptoms (for more details, see Chapter 66, Weakness). Within 72 hours after a cerebellar infarction, cerebellar swelling may develop that can compress the brainstem and produce obstructive hydrocephalus. Therefore, patients with cerebellar infarctions should be examined frequently in an ICU setting, and brain imaging should be repeated. If deterioration occurs, neurosurgical intervention may be warranted. |

|

|

Perilymphatic Fistula |

|

|

Pφ |

A perilymphatic fistula is an abnormal connection between the inner and middle ears that allows escape of perilymph fluid into the middle ear compartment. The episodic vertigo and/or hearing loss provoked by loud sounds occur because sound-induced pressure waves are abnormally distributed through the inner ear. |

|

TP |

Signs suggesting this diagnosis include abrupt onset associated with a history of head trauma or sudden strain during heavy lifting, coughing, or sneezing, and possible association with chronic otitis or cholesteatoma. |

|

Dx |

On physical exam, spontaneous, peripheral nystagmus associated with gait imbalance and unilateral hearing loss is noted. Possible perforation of the tympanic membrane may be noted. The most sensitive test for perilymph fistula is the vertigo and nystagmus induced by pressure in the external ear canal. ENG may show unilateral hypoexcitability; audiography may confirm the sensorineural hearing loss, and CT of the temporal bone may reveal associated skull fracture. |

|

Tx |

The first step in treatment involves bed rest, head elevation, and avoidance of straining. Failure to resolve after several weeks of conservative therapy is an indication to consider a surgical patch. |

Practice-Based Learning and Improvement: Evidence-Based Medicine

Title

Short-term efficacy of Epley’s manoeuvre: a double-blind randomized trial

Authors

von Brevern M, Seelig T, Radtke A, et al.

Institution

Neurologische Klinik, Charité, Campus Virchow-Klinikum, Berlin, Germany

Reference

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 2006;77:980–982

Problem

What maneuvers effectively treat posterior canal BPPV?

Intervention

Sixty-six patients with a diagnosis of BPPV based on a positive Dix-Hallpike maneuver compared a CRP with a sham procedure.

Outcome/effect

After 24 hours, 80% of treated patients were asymptomatic and had no nystagmus with the Dix-Hallpike maneuver, compared with 10% of sham patients. At this point, all patients in both the treatment and control groups with a persistently positive Dix-Hallpike maneuver underwent an Epley maneuver. Ninety-three percent of patients with BPPV from the original control group reported resolution of symptoms 24 hours after undergoing the procedure. By 1 week, 94% of patients in the original treatment group and 82% of patients in the original control group (all of whom underwent the maneuver at 24 hours) were asymptomatic.

Historical significance/comments

The Epley maneuver, or CRP, is used to clear the affected semicircular canal from mobile particles by a set of five successive head positions that are hand-guided by a therapist. At this time, two level I and three level II studies have demonstrated a short-term resolution of symptoms in patients treated in this way. As a result of the above-mentioned and other studies, the American Academy of Neurology released Level A recommendations for the CRP to be established as an effective and safe therapy that should be offered to patients of all ages with posterior semicircular canal BPPV.

Interpersonal and Communication Skills

Base Reassurance on Appropriate Medical Explanations

Although the symptoms of BPPV are extremely uncomfortable and will probably be frightening to the patient and his or her family, the disease does not usually portend serious neurologic impairment. Nonetheless, persons presenting with these symptoms will worry about having a very serious and debilitating illness. Simple reassurance must be accompanied by medical explanations based on an understanding of the patient’s feelings, expectations, and ideas about causality. Reassurance that is perceived to have no real basis may be counterproductive. Failure to explore patients’ ideas, expectations, and beliefs that underlie their concerns, and failure to validate those concerns using empathetic communication, can compromise the patient–physician relationship.

Professionalism

Uphold the Welfare of Patients Who Do Not Speak English

Dizziness and vertigo are complaints that are often evaluated in both the ED and outpatient settings, and their evaluation requires thorough clinical histories. Particularly in these high-volume environments, language barriers can be detrimental to optimal patient care. Studies find that individuals with limited English-speaking ability experience the following:

A greater likelihood of hospital admission,

A greater likelihood of hospital admission,

Frequent misdiagnosis or inappropriate treatment,

Frequent misdiagnosis or inappropriate treatment,

More diagnostic tests and longer lengths of stay, and

More diagnostic tests and longer lengths of stay, and

The Americans with Disabilities Act guarantees that patients will have language accommodations in the health-care setting. Family members, friends, or bilingual staff members who are not trained as interpreters should not be used as interpreters, as they may not be unbiased when issues of decision making and informed consent are involved. Conflict of interest and confidentiality issues are among the concerns brought to the forefront when qualified interpreters are not used. Given the importance of the clinical history when evaluating complaints of dizziness and vertigo, health-care providers should offer the services of a qualified interpreter to patients who do not have English proficiency.

Systems-Based Practice

Patient Satisfaction Is Part of Value-Based Purchasing

Patients with dizziness may require hospital admission for evaluation and management, necessitating interactions with numerous healthcare personnel, including their primary physician, consultants, nurses, and other support staff. Creating an environment for proper communication and patient satisfaction is important to their perception of receiving quality care. HCAPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) is a survey that was developed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and that applies to any acute-care hospital receiving Medicare funding. The survey measures patients’ perceptions of parameters such as pain control, communication with health-care providers, hospital cleanliness, and noise. Results of this survey are part of the value-based purchasing program, in which CMS will make value-based incentive payments to acute-care hospitals based on how well the hospital performs. Because the Affordable Care Act mandated that the hospital value-based purchasing program be budget neutral, it will be funded by Medicare inpatient payment reductions for hospitals not performing at certain levels, beginning with a 1% payment reduction in federal fiscal year 2013.

Lack of follow-up care.

Lack of follow-up care.