35 Diverticulitis

• Diverticulitis is an acute inflammatory process caused by injury and bacterial proliferation in an existing diverticulum.

• Patients with diverticular disease may be seen in the emergency department with inflammation manifested as abdominal pain or, less commonly, with hematochezia.

• Consider complicated disease (perforation of a diverticulum or abscess formation) and surgical consultation in patients who have peritoneal findings on examination.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of diverticulosis is related to age and ranges from 5% at 40 years to 65% by 85 years of age. Approximately 70% of patients with diverticula are asymptomatic, whereas the remainder of patients experience at least one major complication. Twenty percent have diverticulitis and 10% have episodes of bleeding from their diverticula.1 Diverticulitis accounts for 6% of emergency department (ED) visits for acute abdominal pain in the elderly and occurs more frequently than appendicitis in this age group.2

Pathophysiology

Diverticulosis

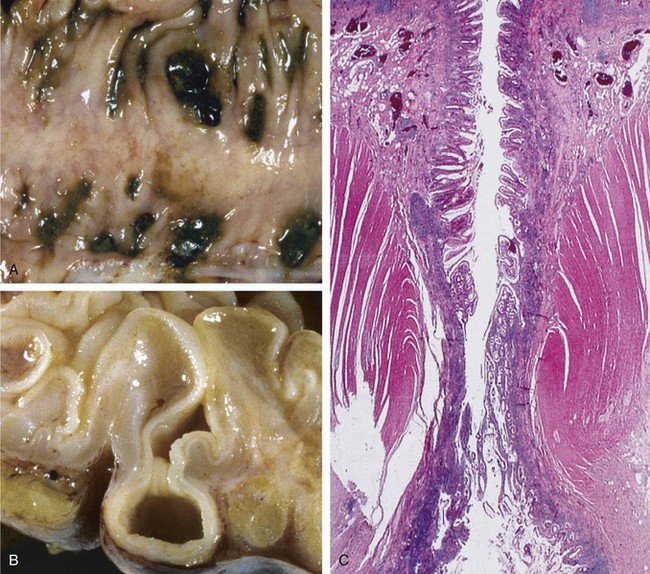

Diverticula are thought to arise from defects in the muscularis layer of the intestines (Fig. 35.1) and are related to abnormalities in muscle tone and increased intraluminal pressure; saclike protrusions eventually form at points of weakness. If stool is caught in these sacs, it becomes inspissated and hardened and causes abrasions of the mucosa that lead to inflammation, although the same end result can occur from pressure differentials alone without the presence of trapped fecal material.

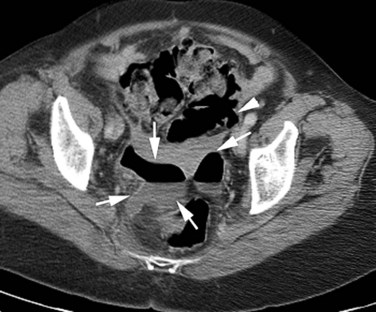

Fig. 35.1 Sigmoid diverticular disease.

(From Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster J. Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease, professional edition. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2009.)

The left side of the colon is the most common site for diverticulosis in patients with westernized diets and lifestyle. Right-sided diverticula occur more frequently in certain Asian populations. Right-sided diverticula have a higher rate of hemorrhage because of anatomic differences in their development.3 Small bowel diverticula occur most commonly in the duodenum, where they are predominantly asymptomatic. About 20% of small bowel diverticula occur in the jejunum or ileum; complications develop in these diverticula at rates three times greater than in duodenal diverticula.4

Diverticulitis

Diverticulitis arises from the initial microperforation of a diverticulum (Table 35.1).5 The process starts with blockage of the colonic opening of the diverticulum or by direct contact with food and fecal particles lodged in the affected portion of the bowel. Increased intraluminal or direct local pressure causes erosion of the diverticular wall, which leads to inflammatory changes, focal necrosis, and eventually perforation. The process is generally mild and limited by local pericolic fat and mesentery. Virtually all cases of diverticulitis involve perforation of the intestines, with the course of the resultant illness determined by the extent of this perforation. Complicated diverticulitis refers to regional spread of the inflammatory process by the formation of larger abscesses, a fistula with adjacent organs, or peritonitis (Fig. 35.2).1,5 Patients with purulent peritonitis have a mortality rate of 6%, which rises to 35% when fecal soilage of the peritoneal cavity occurs. Patients with diverticular disease occasionally have segmental colitis of the sigmoid colon, probably from fecal stasis or localized ischemia. The effects can be mild or may resemble those of inflammatory bowel disease.1

Table 35.1 Classification of the Severity of Colonic Diverticulitis

| STAGE | DEFINITION |

|---|---|

| 1 | Small, confined pericolic abscesses |

| 2 | Larger purulent collections |

| 3 | Generalized suppurative peritonitis |

| 4 | Fecal peritonitis |

Adapted from Hinchey EG, Schaal PGH, Richards GK. Treatment of perforated diverticular disease of the colon. Adv Surg 1978;12:85-109.

Differential Diagnosis

Box 35.1 presents the differential diagnosis for suspicion of diverticulitis.

Box 35.1 Differential Diagnosis for Suspected Diverticulitis

The following diagnoses should be considered in order of urgency:

Diagnostic Testing

Imaging

Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis is the test of choice for confirming the diagnosis of diverticulitis, assessing its severity and complications, and directing intervention. CT findings for and complications of diverticular disease are listed in Box 35.2.

Box 35.2 Computed Tomography in Diverticulitis

Compression ultrasonography is a relatively new diagnostic procedure for diverticular disease. Ultrasonography may be used to serially assess fluid collections or to assist in the transrectal or transvaginal drainage of abscesses. The “pseudokidney” sign (thickening of the bowel wall that mimics the appearance of a kidney) may represent acute diverticulitis and aid in rapid diagnosis by ultrasound. This finding, however, is not specific to diverticular disease.6

Treatment

The majority of patients with acute, uncomplicated diverticulitis respond to bowel rest and antibiotics (Box 35.3).6 The remaining patients require various levels of intervention ranging from percutaneous drainage of abscesses to laparoscopic or other surgical procedures. The surgical mortality rate ranges from 1% to 5%, depending on comorbid conditions and the severity of disease.

Box 35.3 Treatment

Antibiotics for Diverticulitis

Consultation

Surgical consultation should be obtained immediately for patients with peritonitis or a vascular catastrophe. Consultants should be notified early in the treatment of elderly or immunocompromised patients, as well as for patients with clear indications of complicated disease. Twenty-five percent of patients with a new diagnosis of diverticulitis have complicated disease and require surgical intervention. Patients with uncomplicated disease may require only follow-up with a surgeon on an outpatient basis. One third of these patients eventually require surgery.6

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

Establish intravenous access for the management of diverticulitis.

Obtain a pertinent history and perform a physical examination, including rectal and genitourinary examination.

Consider life-threatening conditions in the differential diagnosis.

Obtain surgical consultation for any patients with evidence of peritonitis.

Complications

Overall complications from diverticulosis of the small bowel are unusual when compared with those from disease of the colon. Rarely reported problems include massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage from an arteriovenous malformation located in the submucosa of a jejunal diverticulum, a diverticulum-induced ileoabdominal fistula, and cases of small bowel obstruction with volvulus.4,7–9

Duodenal diverticula have been associated with a higher rate of common bile duct stones identified on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.10,11 This finding may be due to higher rates of bacterial contamination in the biliary system in patients with small bowel diverticula.12 Rarely, congenital intraluminal diverticula may lead to recurrent abdominal pain and obstructive symptoms.

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

![]() Documentation

Documentation

Duration of symptoms, onset, severity

Previous occurrence, history of diverticulosis

Findings on cardiac, abdominal, genitourinary, rectal, and vascular examination

Document multiple repeated examinations

Emergency department course: times of consultations, discussions with family and consultants, availability of testing, delays

Document and address other potentially lethal diagnoses (abdominal aortic aneurysm, mesenteric ischemia)

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Return for worsening pain, fever, vomiting, bloody stool

Treatment of constipation: avoid frequent narcotic use

Complications of disease: abscess, perforation, fistula, bleeding

Complications of pain medications (constipation)

Dietary considerations: high-fiber diet shown to decrease complications associated with diverticular disease

Candidates for outpatient treatment should be restricted to consumption of clear liquids for several days; the diet should be advanced cautiously as tolerated

Bauer VP. Emergency management of diverticulitis. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22:8.

Peterson MA. Disorders of the large intestine. Marx J, Hockberger R, Walls R. Rosen’s textbook of emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice, 7th ed, Philadelphia: Mosby, 2009.

Touzios JG, Dozois EJ. Diverticulosis and acute diverticulitis. Gastroenterol Clin. 2009;38:513–525.

Young-Fadok T, Pemberton JH. Treatment of acute diverticulitis. UpToDate September. www.uptodate.com, 2010. Available at

1 Young-Fadok T, Pemberton JH. Treatment of acute diverticulitis. UpToDate September 2010. Available at www.uptodate.com

2 Bugliosi TF, Meloy TD, Vukov LF. Acute abdominal pain in the elderly. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19:1383–1386.

3 Meyers MA, Alonso DR, Gray GF, et al. Pathogenesis of bleeding colonic diverticulosis. Gastroenterology. 1976;71:577–583.

4 Milovic V, Caspary WF, Stein J. Small bowel diverticula. UpToDate November 2004. Available at www.uptodate.com/

5 Hinchey EJ, Schaal PGH, Richards GK. Treatment of perforated diverticular disease of the colon. Adv Surg. 1978;12:85–109.

6 Joffe S. Imaging in diverticulitis of the colon. eMedicine Radiology online, Aug 2009.

7 Chin NW, Lai CLD, Harisiadis SA, et al. Congenital arteriovenous malformation rupturing into a true jejunal diverticulum. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:972–974.

8 Eriguchi N, Aoyagi S, Nakayama T, et al. Ileo-abdominal wall fistula caused by a diverticulum of the ileum. J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:272–275.

9 Chiu KW, Changchien CS, Chush SIC. Small bowel diverticulum: is it a risk for small bowel volvulus? J Clin Gastroenterol. 1994;19:176–177.

10 Leivonen MK, Halttunen JA, Kivilaakso EO. Duodenal diverticula at endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: analysis of 123 patients. Hepatogastroenterology. 1996;43:961–966.

11 Miyazawa Y, Okinaga K, Nishida K, et al. Recurrent common bile duct stones associated with periampullary duodenal diverticula and calcium bilirubinate stones. Int Surg. 1995;80:120–124.

12 Palder SB, Frey CB. Jejunal diverticulosis. Arch Surg. 1988;123:889–894.