Disturbances of vision

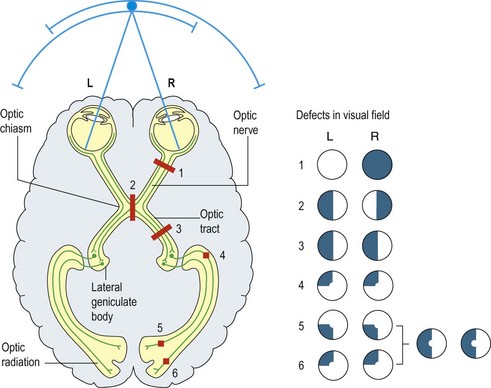

Common visual symptoms are loss of vision, blurring of vision or loss of part of the visual field. Occasionally more complex disturbances such as hallucinations or inattention may occur. Loss of vision may affect one eye or one visual field and patients may misinterpret this, for example mistaking a right homonymous hemianopia for a defect of vision in the right eye. It is important to establish which they mean, in order to decide which part of the visual pathway is affected (Fig. 1). The timing, evolution and duration of visual loss are crucial in diagnosis.

Monocular visual loss

Monocular visual loss may be due to a lesion affecting one eye or the optic nerve anterior to the optic chiasm. The pupil response is usually normal in disease of the eye itself but is usually impaired in optic nerve disease, either as a complete or relative afferent pupillary defect (p. 14).

Acute reversible monocular visual loss

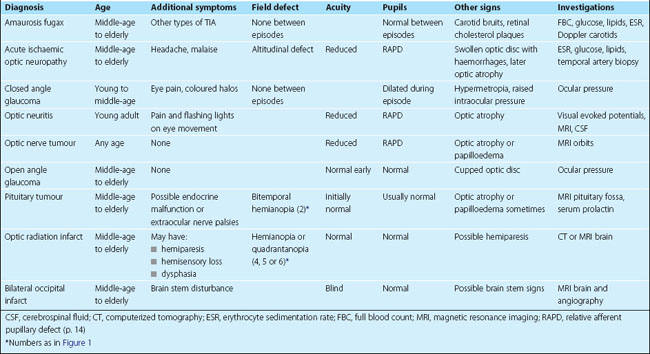

Amaurosis fugax causes sudden, reversible loss, lasting up to 30 min with complete and rapid recovery. It is usually due to embolism from the ipsilateral carotid artery to the retinal artery but may be associated with other causes of a transient ischaemic attack (TIA; p. 70). The patient describes a curtain coming down over their vision and episodes often recur. Typically the patient has no ocular signs at the time of being seen, but there may be cholesterol plaques from fragmented emboli in the retinal arterioles or carotid bruits to support the diagnosis. This should be investigated as a carotid artery TIA because there is a risk of subsequent middle cerebral artery infarction.

Acute-onset, persistent monocular visual loss

Anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy evolves over minutes to days. An altitudinal field defect, where the upper or lower half of the visual field is lost, is characteristic; patients feel as if they are looking over a wall. There is often optic nerve head swelling with some fundal haemorrhages. In patients under the age of 55 years, this is likely to be due to atheromatous disease, but in older patients, it may be due to giant cell arteritis (GCA). In both types, the condition may spread rapidly to affect both eyes but it is especially urgent to diagnose GCA because it is treatable with high-dose corticosteroids. There is usually associated headache and weight loss and an elevated blood erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or plasma viscosity. An urgent temporal artery biopsy confirms the diagnosis in 60–80% of cases but treatment should not wait for results of the biopsy (p. 40).

Ocular causes of sudden-onset visual loss include retinal detachment, vitreous haemorrhage and retinal vein thrombosis (p. 17).

Binocular visual loss

In these patients, the defect is usually asymmetrical. Bilateral optic nerve lesions cause optic atrophy, reduced acuity, incongruous field defects with central scotomas that cross the midline, colour desaturation and abnormal pupil responses. Common neurological causes are optic neuritis and idiopathic intracranial hypertension (p. 40).

Slowly progressive binocular visual loss

Chiasmal lesions commonly cause a bitemporal hemianopia, but if the lesion is not exactly central, the involvement of one eye may be greater than of the other. The field defect is often clearest on testing the central field to red pin. There is frequently reduced acuity and there may be optic atrophy. The most common cause is a benign pituitary adenoma and there may be associated endocrine disturbance (p. 96).

Slowly progressive hemianopic defects usually reflect tumours of the retrochiasmal visual pathways.

Other visual disturbances

Visual hallucinations

These may be due to lesions in any part of the visual system. They may be simple patches of colour or light, or complex images. They are most commonly seen in migraine or epilepsy but may occur in any visual disturbance, usually being restricted to the abnormal visual field. They may also be part of an encephalopathy (p. 52).

Some investigations of visual disturbance

Neuroimaging. MRI is the best modality for imaging the optic chiasm or optic nerve; views are as indicated.

Neuroimaging. MRI is the best modality for imaging the optic chiasm or optic nerve; views are as indicated. Visual evoked potentials can give information about optic pathway function, especially optic nerve demyelination.

Visual evoked potentials can give information about optic pathway function, especially optic nerve demyelination.Disturbances of vision

The pattern of visual field loss usually gives the anatomical location of the lesion and the timing gives a clue to the pathology.

The pattern of visual field loss usually gives the anatomical location of the lesion and the timing gives a clue to the pathology. Pupillary responses to light and visual acuity are normal with lesions posterior to the optic chiasm.

Pupillary responses to light and visual acuity are normal with lesions posterior to the optic chiasm.