Chapter 429 Disturbances of Rate and Rhythm of the Heart

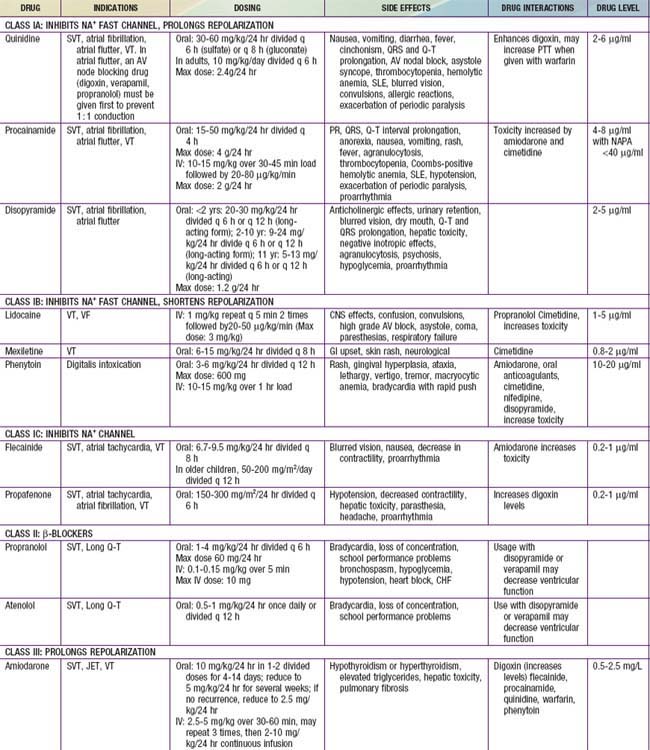

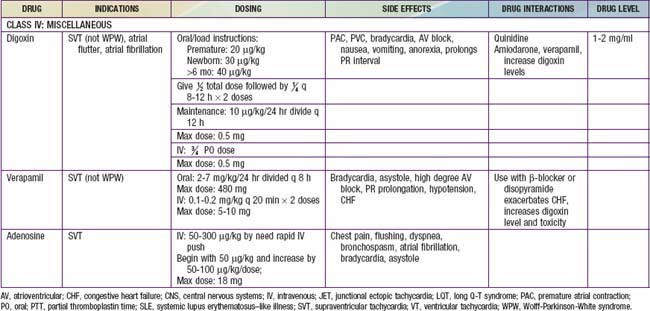

A number of effective pharmacologic agents are available for treating arrhythmias in adults; many have not been studied extensively in children. Insufficient data are available regarding pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and efficacy in the pediatric population, and therefore the selection of an appropriate agent is often necessarily empirical. Fortunately, the majority of rhythm disturbances in children can be reliably controlled with a single agent (Table 429-1). Transcatheter ablation is acceptable therapy not only for life-threatening or drug-resistant tachyarrhythmias but also for the elective definitive treatment of arrhythmias. For patients with bradycardia, implantable pacemakers are small enough for use in premature infants. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) are available for use in high-risk patients with malignant ventricular arrhythmias and an increased risk of sudden death.

429.1 Principles of Antiarrhythmic Therapy

Antiarrhythmic drugs are commonly categorized using the Vaughan Williams classification system. This system comprises 4 classes: Class I includes agents that primarily block the sodium channel, class II includes the β-blockers, class III includes those agents that prolong repolarization, and class IV are the calcium channel blockers. Class I is further divided by the strength of the sodium channel blockade (see Table 429-1).

429.2 Sinus Arrhythmias and Extrasystoles

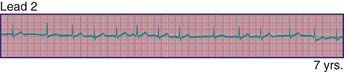

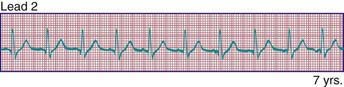

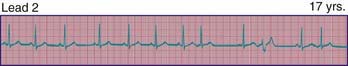

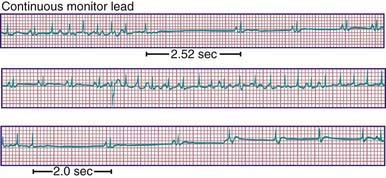

Phasic sinus arrhythmia represents a normal physiologic variation in impulse discharges from the sinus node related to respirations. The heart rate slows during expiration and accelerates during inspiration. Occasionally, if the sinus rate becomes slow enough, an escape beat arises from the atrioventricular (AV) junction region (Fig. 429-1). Normal phasic sinus arrhythmia can be quite prominent in children and may mimic frequent premature contractions, but the relationship to the phases of respiration can be appreciated with careful auscultation. Drugs that increase vagal tone, such as digoxin, may exaggerate sinus arrhythmia; it is usually abolished by exercise. Other irregularities in sinus rhythm, especially bradycardia associated with periodic apnea are commonly seen in premature infants.

Wandering atrial pacemaker (Fig. 429-2) is defined as an intermittent shift in the pacemaker of the heart from the sinus node to another part of the atrium. It is not uncommon in childhood and usually represents a normal variant; it may also be seen in association with sinus bradycardia in which the shift in atrial focus is an escape phenomenon.

Premature atrial contractions are common in childhood, usually in the absence of cardiac disease. Depending on the degree of prematurity of the beat (coupling interval) and the preceding R-R interval (cycle length), premature atrial complexes may result in a normal, a prolonged (aberrancy), or an absent (blocked premature atrial complex) QRS complex. The last occurs when the premature impulse cannot conduct to the ventricle due to refractoriness of the AV node or distal conducting system (Fig. 429-3). Atrial extrasystoles must be distinguished from premature ventricular contractions (PVCs). Careful scrutiny of the electrocardiogram for a premature P wave preceding the QRS will either show a premature P wave superimposed on, and deforming, the preceding T wave, or a P wave that is premature and has a different contour from that of the other sinus P waves. Atrial premature complexes usually reset the sinus node pacemaker, leading to an incomplete compensatory pause, but this feature is not regarded as a reliable means of differentiating atrial from ventricular premature complexes in children.

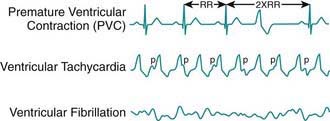

PVCs may arise in any region of the ventricles. They are characterized by premature, widened, bizarre QRS complexes that are not preceded by a premature P wave (Fig. 429-4). When all premature beats have identical contours, they are classified as uniform, suggesting origin from a common site. When PVCs vary in contour, they are designated as multiform, suggesting origin from more than 1 ventricular site. Ventricular extrasystoles are often, but not always, followed by a full compensatory pause. The presence of fusion beats, that is, complexes with morphologic features that are intermediate between those of normal sinus beats and those of PVCs, proves the ventricular origin of the premature beat. Extrasystoles produce a smaller stroke and pulse volume than normal and, if quite premature, may not be audible with a stethoscope or palpable at the radial pulse. When frequent, extrasystoles may assume a definite rhythm, for example, alternating with normal beats (bigeminy) or occurring after 2 normal beats (trigeminy). Most patients are unaware of single premature ventricular contractions, although some may be aware of a “skipped beat” over the precordium. This sensation is due to the increased stroke volume of the normal beat after a compensatory pause. Anxiety, a febrile illness, or ingestion of various drugs or stimulants may exacerbate PVCs.

429.3 Supraventricular Tachycardia

Clinical Manifestations

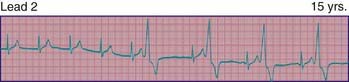

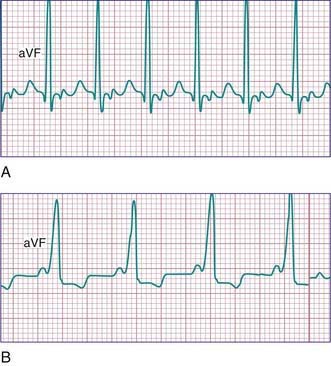

The typical electrocardiographic features of the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome are seen when the patient is not having tachycardia. These features include a short P-R interval and slow upstroke of the QRS (delta wave) (Fig. 429-5). Though most often present in patients with a normal heart, this syndrome may also be associated with Ebstein anomaly of the tricuspid valve, or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The critical anatomic structure is an accessory pathway consisting of a muscular bridge connecting atrium to ventricle on either the right or the left side of the AV ring (Fig. 429-6). During sinus rhythm, the impulse is carried over both the AV node and the accessory pathway; it produces some degree of fusion of the 2 depolarization fronts that results in an abnormal QRS. During AVRT, an impulse is carried in antegrade fashion through the AV node (orthodromic conduction), which results in a normal QRS complex, and in retrograde fashion through the accessory pathway to the atrium, thereby perpetuating the tachycardia. In these cases, only after cessation of the tachycardia are the typical ECG features of WPW syndrome recognized (see Fig. 429-5). When rapid antegrade conduction occurs through the pre-excitation pathway during tachycardia and the retrograde re-entry pathway to the atrium is via the AV node (antidromic conduction), the QRS complexes are wide and the potential for more serious arrhythmias (ventricular fibrillation) is greater, especially if atrial fibrillation occurs.

Treatment

Vagal stimulation by placing of the face in ice water (in older children) or by placing an ice bag over the face (in infants) may abort the attack. To terminate the attack, older children may be taught vagal maneuvers such as the Valsalva maneuver, straining, breath holding, or standing on their head. Ocular pressure must never be performed, and carotid sinus massage is very rarely effective. When these measures fail, several pharmacologic alternatives are available (see Table 429-1). In stable patients, adenosine by rapid intravenous push is the treatment of choice because of its rapid onset of action and minimal effects on cardiac contractility. The dose may need to be increased if no effect on the tachycardia is seen. Because of the potential for adenosine to initiate atrial fibrillation, it should not be administered without a means for DC cardioversion near at hand. Calcium channel blockers such as verapamil have also been used in the initial treatment of SVT in older children. Verapamil may reduce cardiac output and produce hypotension and cardiac arrest in infants younger than 1 yr; it is therefore contraindicated in this age group. In urgent situations when symptoms of severe heart failure have already occurred, synchronized DC cardioversion (0.5-2 J/kg) is recommended as the initial management (Chapter 62).

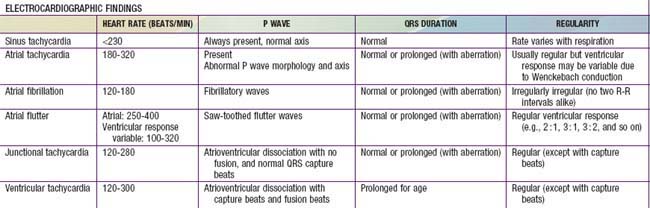

Atrial flutter, also known as intra-atrial re-entrant tachycardia, is an atrial tachycardia characterized by atrial activity at a rate of 250-300 beats/min in children and adolescents, and 400-600 in neonates. The mechanism of common atrial flutter consists of a re-entrant or rhythm originating in the right atrium circling the tricuspid valve annulus. Because the AV node cannot transmit such rapid impulses, some degree of AV block is virtually always present, and the ventricles respond to every 2nd-4th atrial beat (Fig. 429-7). Occasionally, the response is variable and the rhythm appears irregular.

Atrial fibrillation is uncommon in children and is rare in infants. The atrial excitation is chaotic and more rapid (400-700 beats/min) and produces an irregularly irregular ventricular response and pulse (Fig. 429-8). This rhythm disorder is often associated with atrial enlargement or disease. Atrial fibrillation may be seen in older children with rheumatic mitral valve stenosis. It is also seen rarely as a complication of atrial surgery, in patients with left atrial enlargement secondary to left AV valve insufficiency, and in patients with WPW syndrome. Thyrotoxicosis, pulmonary embolism, pericarditis, or cardiomyopathy may be suspected in a previously normal older child or adolescent with atrial fibrillation. Very rarely, atrial fibrillation may be familial. The best initial treatment is rate control, most effectively with calcium channel blockers, to limit the ventricular rate during atrial fibrillation. Digoxin is not given if WPW syndrome is present. Normal sinus rhythm may be restored with intravenous procainamide or amiodarone, or by DC cardioversion, and DC cardioversion is the first choice in hemodynamically unstable patients. Patients with chronic atrial fibrillation are at risk for the development of thromboembolism and stroke and should undergo anticoagulation with warfarin. Patients being treated by elective cardioversion should also undergo anticoagulation.

429.4 Ventricular Tachyarrhythmias

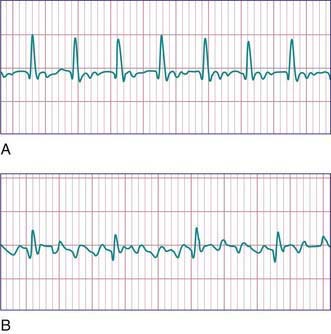

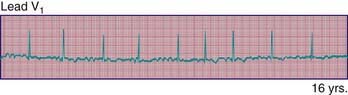

Ventricular tachycardia (VT) is less common than SVT in pediatric patients. VT is defined as at least three PVCs at >120 beats/min (Fig. 429-9). It may be paroxysmal or incessant. VT may be associated with myocarditis, anomalous origin of a coronary artery, arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia, mitral valve prolapse, primary cardiac tumors, or cardiomyopathy. It has been seen with prolonged Q-T interval of either congenital or acquired (proarrhythmic drugs) causation, WPW syndrome, and drug use (cocaine, amphetamines). It may develop years after intraventricular surgery (especially tetralogy of Fallot and related defects) or occur without obvious organic heart disease. VT must be distinguished from SVT with aberrancy or rapid conduction over an accessory pathway (Table 429-2). The presence of clear capture and fusion beats confirms the diagnosis of VT. Although some children tolerate rapid ventricular rates for many hours, this arrhythmia should be promptly treated because hypotension and degeneration into ventricular fibrillation may result. For patients who are hemodynamically stable, intravenous amiodarone, lidocaine, or procainamide are the initial drugs of choice. If treatment is to be successful, it is critical to search for and correct any underlying abnormalities such as electrolyte imbalance, hypoxia, or drug toxicity. Amiodarone is the treatment of choice during cardiac arrest (Chapter 62). Hemodynamically unstable patients with VT should be immediately treated with DC cardioversion. Overdrive ventricular pacing, through temporary pacing wires or a permanent pacemaker, may also be effective, although it may cause the arrhythmia to deteriorate into ventricular fibrillation. In the neonatal period, ventricular tachycardia may be associated with an anomalous left coronary artery (Chapter 426.2) or a myocardial tumor.

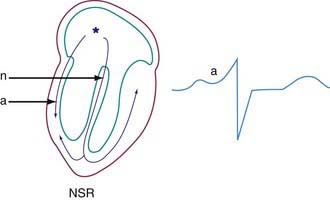

Figure 429-9 Ventricular arrhythmias.

(From Park MY: Pediatric cardiology for practitioners, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2008, Mosby/Elsevier, p 429, Fig 24-6.)

Ventricular fibrillation is a chaotic rhythm that results in death unless an effective ventricular beat is rapidly re-established (see Fig. 429-9). A thump on the chest may occasionally restore sinus rhythm. Usually, cardiopulmonary resuscitation and DC defibrillation is necessary. If defibrillation is ineffective or fibrillation recurs, amiodarone or lidocaine may be given intravenously and defibrillation repeated (Chapter 62). After recovery from ventricular fibrillation, a search should be made for the underlying cause. Electrophysiologic study is indicated for patients who have survived ventricular fibrillation unless a clearly reversible cause is identified. If WPW syndrome is noted, catheter ablation should be performed. For patients in whom no correctable abnormality can be found, an ICD is nearly always indicated, because of the high risk of sudden death.

429.5 Long Q-T Syndromes

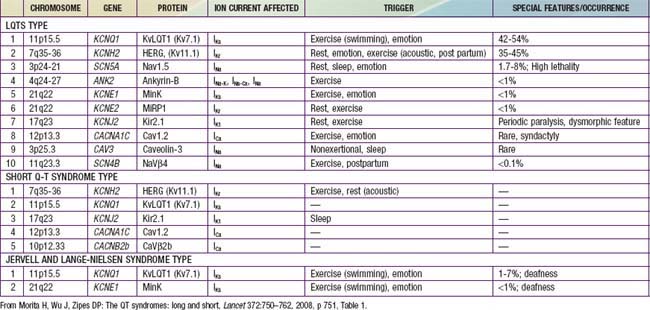

Long Q-T syndromes (LQTS) are genetic abnormalities of ventricular repolarization, with an estimated incidence of about 1 per 10,000 births (Table 429-3). They present as a long Q-T interval on the surface ECG and are associated with malignant ventricular arrhythmias (torsades de pointes and ventricular fibrillation). They are a cause of syncope and sudden death and may be associated with sudden infant death syndrome or drowning. At least 50% of cases are familial, but due to variable penetrance, this may be an underestimate. The old distinction between dominant and recessive forms of the disease (Romano-Ward syndrome [RWS] vs Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome [JLNS]) is no longer commonly made, as the latter “recessive” condition is known to be due to the homozygous state. JLNS is associated with congenital sensorineural deafness. Asymptomatic patients carrying the gene mutation may not all have a prolonged Q-T duration. Q-T interval prolongation may become apparent with exercise or during catecholamine infusions.

Genetic studies have identified mutations in cardiac potassium and sodium channels (see Table 429-3). Additional forms of LQTS have been described, but these are much more uncommon. JLNS has been seen in patients who have homozygous mutations of KVLQT1 and minK, whereas the heterozygous state is manifested as RWS. Genotype may predict clinical manifestations; for example, LQT1 events are usually stress induced, whereas events in LQT3 often occur during sleep. LQT2 events have an intermediate pattern. LQT3 has the highest probability for sudden death, followed by LQT2 and then LQT1. Drugs may prolong the Q-T interval directly but more often do so when drugs such as erythromycin or ketoconazole inhibit their metabolism (Table 429-4).

Table 429-4 ACQUIRED CAUSES OF Q-T PROLONGATION*

DRUGS

ELECTROLYTE DISTURBANCES

UNDERLYING MEDICAL CONDITIONS

* A more exhaustive updated list of medications that can prolong the QTc interval is available at the University of Arizona Center for Education and Research of Therapeutics website (www.azcert.org).

From Park MY: Pediatric cardiology for practitioners, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2008, Mosby/Elsevier, p 433, Box 24-1.

Short Q-T syndromes (see Table 429-3) manifest with atrial or ventricular fibrillation and are associated with syncope and sudden death.

429.6 Sinus Node Dysfunction

Sick sinus syndrome is the result of abnormalities in the sinus node or atrial conduction pathways, or both. This syndrome may occur in the absence of congenital heart disease and has been reported in siblings, but it is most commonly seen after surgical correction of congenital heart defects, especially the Fontan procedure and the atrial switch (Mustard or Senning) operation for transposition of the great arteries. Clinical manifestations depend on the heart rate. Most patients remain asymptomatic without treatment, but dizziness and syncope can occur during periods of marked sinus slowing with failure of junctional escape (Fig. 429-10). Pacemaker therapy is indicated in patients who experience symptoms such as exercise intolerance or syncope.

429.7 AV Block

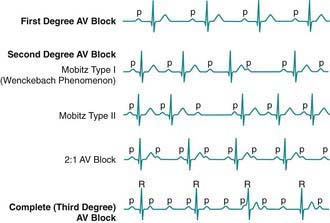

AV block may be divided into 3 forms. In 1st-degree AV block, the PR interval is prolonged, but all the atrial impulses are conducted to the ventricle (Fig. 429-11). In 2nd-degree AV block, not every atrial impulse is conducted to the ventricle. In 1 variant of 2nd-degree block known as the Wenckebach type (also called Mobitz type I), classically the PR interval increases progressively until a P wave is not conducted. In the cycle following the dropped beat, the PR interval normalizes (see Fig. 429-11). In Mobitz type II, there is no progressive conduction delay and subsequent shortening of the PR interval after a blocked beat. This conduction defect is less common but has more potential to cause syncope and may be progressive. A related condition is high-grade 2nd-degree AV block, in which more than 1 P wave in a row fails to conduct. This is even more worrisome. In 3rd-degree AV block (complete heart block), no impulses from the atria reach the ventricles (see Fig. 429-11). Generally, an independent escape rhythm is present, but may not be reliable, leading to symptoms such as syncope.

Figure 429-11 Atrioventricular (AV) block.

(From Park MY: Pediatric cardiology for practitioners, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2008, Mosby/Elsevier, p 446, Fig. 25-1.)

Congenital complete AV block in children is presumed to be caused by autoimmune injury of the fetal conduction system by maternally derived IgG antibodies (anti-SSA/Ro, anti-SSB/La) in a mother with overt or, more often, asymptomatic SLE or Sjögren syndrome. Autoimmune disease accounts for 60-70% of all cases of congenital complete heart block and ≈80% of cases in which the heart is structurally normal (Fig. 429-12). A homeobox gene mutation, NKX2-5, is described in which congenital AV block is seen most commonly in association with atrial septal defects. Complete AV block is also seen in patients with complex congenital heart disease and abnormal embryonic development of the conduction system. It has been associated with myocardial tumors and myocarditis. It is a known complication of myocardial abscess secondary to endocarditis. It is also seen in genetic abnormalities including LQTS and Kearn-Sayre syndrome. It is also a complication of congenital heart disease repair and, in particular, repairs involving VSD closure.

The diagnosis is confirmed by electrocardiography; the P waves and QRS complexes have no constant relationship (see Fig. 429-12). The QRS duration may be prolonged, or it may be normal if the heartbeat is initiated high in the AV node or bundle of His.

Abrams DJ, Perkin MA, Skinner JR. Long QT syndrome. BMJ. 2010;340:b4815. doi:10.1136/bmj.b4815

Ackerman MJ. Molecular basis of congenital and acquired long QT syndromes. J Electrocardiol. 2004;37(Suppl):1-6.

Bar-Cohen Y, Walsh EP, Love BA, et al. First appropriate use of automated external defibrillator in an infant. Resuscitation. 2005;67:135-137.

Benson DWJr, Smith WM, Dunnigan A, et al. Mechanisms of regular, wide QRS tachycardia in infants and children. Am J Cardiol. 1982;49:1778-1788.

Buyon JP, Friedman DM. Autobody associated congenital heart block: the clinical perspective. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2003;5:374-378.

Chen PS, Priori SG. The Brugada syndrome. J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1176-1180.

Chui SN, Wang JK, Wu MH, et al. Cardiac conduction disturbance detected in a pediatric population. J Pediatr. 2008;152:85-89.

Chun TU, Van Hare GF. Advances in the approach to treatment of supraventricular tachycardia in the pediatric population. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2004;6:322-326.

Clarke DA, Medow MS, Taneja I, et al. Initial orthostatic hypotension in the young is attenuated by static handgrip. J Pediatr. 2010;156:1019-1022.

Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine and Section on Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery. Ventricular fibrillation and the use of automated external defibrillators on children. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1159-1161.

Deal BJ, Mavroudis C, Backer CL. The role of concomitant arrhythmia surgery in patients undergoing repair of congenital heart disease. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2008;31(Suppl 1):S13-S16.

Delacrétaz E. Clinical practice. Supraventricular tachycardia. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1039-1051.

Dobrev D, Nattel S. New antiarrhythmic drugs for treatment of atrial fibrillation. Lancet. 2010;375:1212-1220.

Dunnigan A, Benson DWJr, Banditt DG. Atrial flutter in infancy: diagnosis, clinical features, and treatment. Pediatrics. 1985;75:725-729.

Ellinor PT, Lunetta KL, Glazer NL, et al. Common variants in KCNN3 are associated with lone atrial fibrillation. Nat Genet. 2010;42:240-244.

Eronen M, Siren MK, Ekblad H, et al. Short- and long-term outcome of children with congenital complete heart block diagnosed in utero as a newborn. Pediatrics. 2000;106:86-91.

Esberger D, Jones S, Morris F, et al. Junctional tachycardias. Br Med J. 2002;324:662-665.

Friedman RA, Walsh EP, Silka MJ, et al. NASPE Expert Consensus Conference: Radiofrequency catheter ablation in children with and without congenital heart disease. Report of the writing committee. North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2002;25(6):1000-1017.

Fu Q, VanGundy TB, Galbreath M, et al. Cardiac origins of the postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(25):2858-2868.

Goldberger Z, Lampert R. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. JAMA. 2006;295:809-818.

Goodacre S, McLeod K. Paediatric electrocardiography. Br Med J. 2002;324:1382-1385.

Hodgson-Zingman DM, Karst ML, Zingman LV, et al. Atrial natriuretic peptide frameshift mutation in familial atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:158-165.

Imboden M, Swan H, Denjoy I, et al. Female predominance and transmission distortion in the long-QT syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2744-2751.

Kaultman H, Shah M. Evaluation of the child with an arrhythmia. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2004;51:1537-1551.

Kirk CR, Gibbs JL, Thomas R. Cardiovascular collapse after verapamil in supraventricular tachycardia. Arch Dis Child. 1987;62:1265-1266.

Lafuente-Lafuente C, Mahé I, Extramiana F. Management of atrial fibrillation. BMJ. 2010;340:40-45.

Lopes LM, Tavares GMP, Damiano AP, et al. Perinatal outcome of fetal atrioventricular block one-hundred-sixteen cases from a single institution. Circulation. 2008;118:1268-1275.

MacCormick JM, McAlister H, Crawford J, et al. Misdiagnosis of long QT syndrome as epilepsy at first presentation. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:26-32.

Marine JE. Catheter ablation therapy for supraventricular arrhythmias. JAMA. 2007;298:2768-2778.

Martin K, Bates G, Whitehouse WP. Transient loss of consciousness and syncope in children and young people: what you need to know. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2010;95:66-72.

Meadow MS. Postural tachycardia syndrome from a pediatrics perspective. J Pediatr. 2011;158(1):4-5.

Miller MD, Porter CJ, Ackerman MJ. Diagnostic accuracy of screening electrocardiograms in long QT syndrome I. Pediatrics. 2001;108:8-12.

Morita H, Wu J, Zipes DP. The QT syndromes: long and short. Lancet. 2008;372:750-762.

Ojha A, Chelimsky TC, Chelimsky G. Comorbidities in pediatric patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. J Pediatr. 2011;158:119-122.

Perry JC, Garson AJr. Supraventricular tachycardia due to Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in children: early disappearance and late recurrence. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;16:1215-1220.

Probst V, Denjoy I, Meregalli PG, et al. Clinical aspects and prognosis of Brugada syndrome in children. Circulation. 2007;115:2042-2048.

Quaglini S, Rognoni C, Spazzolini C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of neonatal ECG screening for the long QT syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1824-1832.

Roden DM. Drug-induced prolongation of the QT interval. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1013-1022.

Salerno JC, Seslar SP. Supraventricular tachycardia. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:268-274.

Skinner JR, Chung SK, Nel CA, et al. Brugada syndrome masquerading as febrile seizures. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1206-e1211.

Tester DJ, Ackerman MJ. The role of molecular autopsy in unexplained sudden cardiac death. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2006;21:166-172.

Thavendiranathan P, Bagai A, Khoo C, et al. Does this patient with palpitations have a cardiac arrhythmia? JAMA. 2009;302:2135-2142.

Trohman RG, Kim MH, Pinski SL. Cardiac pacing: the state of the art. Lancet. 2004;364:1701-1718.

Van Hare GF, Dubin AM, Collins KK. Invasive electrophysiology in children: state of the art. J Electrocardiol. 2002;35(Suppl):165-174.

Van Norstrand DW, Ackerman MJ. Sudden infant death syndrome: do ion channels play a role? Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:272-278.

Vetter VL, Elia J, Erickson C, et al. Cardiovascular monitoring of children and adolescents with heart disease receiving stimulant drugs: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young Congenital Cardiac Defects Committee and the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing. Circulation. 2008;117(18):2407-2423.

Walsh EP, Cecchin F. Recent advances in pacemaker and implantable defibrillator therapy for young patients. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2004;19:91-96.

Westby M, Bullock I, Cooper PN, et al. Transient loss of consciousness—initial assessment, diagnosis, and specialist referral: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2010;341:552-556.

Wilde AAM, Bhuiyan ZA, Crotti L, et al. Left cardiac sympathetic denervation for catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2024-2029.

Wolf CM, Berul CI. Inherited conduction system abnormalities—one group of diseases, many genes. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:446-455.