CHAPTER 1 Distal Radius Fractures: A Historical Perspective

Most discussions of distal radius fractures start with Colles’ description published in 1814 under the title “On the Fracture of the Carpal Extremity of the Radius” and its now well-known proclamation that

“One consolation only remains, that the limb at some remote period again enjoy perfect freedom in all its motions, and be completely exempt from pain.”1

Fracture Description

In the Beginning

Distal radius fractures were historically thought of as dislocations of the wrist, from Hippocrates’ time until the 18th century, when Petit first posed the possibility that they may be fractures.2 The memoir of Pouteau, chief surgeon of L’Hotel Dieu in Lyon, published in 1783, described distal radius fractures as such, and recognized that there were several types.3 This memoir predates Colles’ article by 30 years, and in France, distal radius fractures are still often referred to as Pouteau-Colles fractures.4

Abraham Colles (Fig. 1-1) was born in 1773, near Kilkerny, Ireland; he presumably became interested in medicine after receiving an anatomy book in gratitude from the town surgeon after a flood swept away all of the surgeon’s possessions. Colles trained in Dublin and Edinburgh, obtained his medical degree in 1797, and was elected president of the Royal College of Surgeons of Ireland in 1802 at age 29. His landmark work on distal radius fractures was published in 1814,1 preceded by an article on surgical anatomy in 1811, and followed by an article on clubfoot (1818) and a text on venereal disease and the use of mercury (1837). His contribution to orthopaedics does not include an illustration or any description of the dissection of the injury, which is surprising given his reputation as an anatomist. His work is an explanation for his logic as to why the injury is likely a fracture rather than a dislocation. Colles made this assumption based on the presence of crepitus typical to well-described fractures at the time. He discussed the tendency of the wrist to revert to its deformity at the time of injury in the absence of appropriate immobilization, and the importance of guarding “against the carpal end of the radius being drawn backwards,” recognizing the deleterious effect of loss of palmar tilt.

Colles concluded his work with the following remarks:

“I cannot conclude these observations without remarking that were my opinion to be drawn from those cases only which have occurred to me, I should consider this as by far the most common injury to which the wrist or carpal extremities are exposed. During the last three years I have not met a single instance of Desault’s dislocation of the inferior end of the radius while I have had opportunities of seeing a vast number of the fracture of the lower end of this bone.”1

“One would have thought that the observations of these writers [Petit, Pouteau, and Desault] would have raised some doubts in the minds of modern surgeons on this obscure point of doctrine: but not so; for we find Richerand, Boyer, Delpech, Leveille, Monteggia and Samuel Cooper adhering to old errors; and they have unanimously admitted four dislocations at the wrist.”5

Goyrand in the 1830s noted that most cases of distal radius fractures had dorsal displacement, but also described occasional cases of palmar displacement and illustrated both.6,7 Nelaton contributed to the anatomical study of these injuries and to the study of the mechanism of injury using cadavers with his paper in 1844.8 In 1838, Barton of the United States described a fracture-dislocation of the radiocarpal joint, saying, as many authors (including Colles) prior had, that these injuries are often mistaken for sprains or dislocations of the wrist. Barton distinguished the injury under discussion, however, by describing a subluxation of the wrist resulting from a fracture through the distal radial articular surface, not to be mistaken for fractures “of the radius, or of the radius and ulna, just above, and not involving the joint.”9 Smith published a chapter, “Fractures of the Bones of the Forearm, in the Vicinity of the Wrist-Joint,” in 1847 describing the anatomy of Colles’ fracture and a palmarly displaced distal radius fracture, although he did not have the benefit of an anatomical specimen as Goyrand did a decade earlier.10

And Then There Was Röntgen

The discovery and development of roentgenography in late 1895 was a significant advance in the nature of fracture evaluation and treatment. Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen (Fig. 1-2) was born in Prussia and emigrated to Holland with his family as political refugees. He became Professor of Physics at Wurzburg in 1888 and developed a practical use for roentgenography in the early winter of 1895. He submitted his first paper on the topic to the local scientific community on December 28, 1895. The idea took hold quickly, and within months larger hospitals obtained and used the technology. His wife recalled:

“When Willi told me in November that his work was going well, we had no idea of the consequences it would bring. But scarcely had he published the results of his research than our peace of mind was at an end…. It is no small matter to become a great man.”9

Röntgen received the Nobel Prize in 1901 for his work.

Beck and Cotton were two of the first to use roentgenograms for further investigation of distal radius fractures, publishing their findings independently from 1898 through 1900.11–14 Cotton focused not only on the radiographic characteristics of this injury, but also on the experimental and anatomical correlations with roentgenograms on 140 patients with distal radius fractures. Several other authors studied the radiographic characteristics of these fractures, including Morton,15 Pilcher,16 and Destot.17

Classification Systems

Numerous classification systems have been published over the years, and orthopaedic surgeons have employed them, trying to realize Burstein’s ideal description of a successful classification system18: one that is functional (with high interobserver and intraobserver reliability) and useful (one that helps determine treatment and predict outcomes of that treatment). Today, no one classification system seems to fit that description perfectly, and orthopaedists draw on a multitude of classifications to help describe and treat distal radius fractures.

In 1939, the classification system of Nissen-Lie19 was published; this system was based on the presence or absence of intra-articular involvement, metaphyseal comminution, or singular deformity, similar to the system proposed by Gartland and Werley20 in 1951 in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Table 1-1). This was followed by Lidstrom’s system,21 published in 1959, which expanded the evaluation criteria to describe better the direction of displacement and involvement of the joint surface.

| Group | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Simple Colles’ fracture with no involvement of the radial articular surface |

| 2 | Comminuted Colles’ fracture with involvement of the radial articular surface |

| 3 | Comminuted Colles’ fracture with involvement of the radial articular surface with displacement of the fragments |

| 4 | Extra-articular, nondisplaced (added by Solgaard in 1985) |

Adapted from Gartland JJ, Werley CW: Evaluation of healed Colles’ fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1951; 33:895–907.

Older and colleagues22 published their classification of extra-articular distal radius fractures in 1965. This classification divides fractures into four types, each with two to four subtypes, based on extent of displacement, dorsal angulation, shortening of the distal fragment of the radius, and presence and extent of comminution of the dorsal metaphyseal cortex. This system has subsequently been tested for consistency and has been evaluated prospectively. Prospective studies from the late 1980s and early 1990s showed that presence of initial dorsal comminution and the extent of the initial deformity are the best indicators for later loss of reduction (Table 1-2).23–27

TABLE 1-2 Older Classification

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| I | Nondisplaced |

| 1. Loss of some volar angulation and ≤5 degrees of dorsal angulation | |

| 2. No significant shortening: ≥2 mm above the distal radius | |

| II | Displaced with minimal comminution |

| 1. Loss of volar angulation | |

| 2. Shortening: usually not below the distal ulna, but occasionally ≤3 mm below it | |

| 3. Minimal comminution of the dorsal radius | |

| III | Displaced with comminution of the distal radius |

| 1. Comminution of the distal radius | |

| 2. Shortening: usually below the distal ulna | |

| 3. Comminution of the distal radius fragment: usually not marked and often characterized by large pieces | |

| IV | Displaced with severe comminution of the radial head |

| 1. Comminution of the dorsal radius: marked | |

| 2. Comminution of the distal radius fragment: shattered | |

| 3. Shortening: usually 2-8 mm below the distal ulna | |

| 4. Poor volar cortex in some cases |

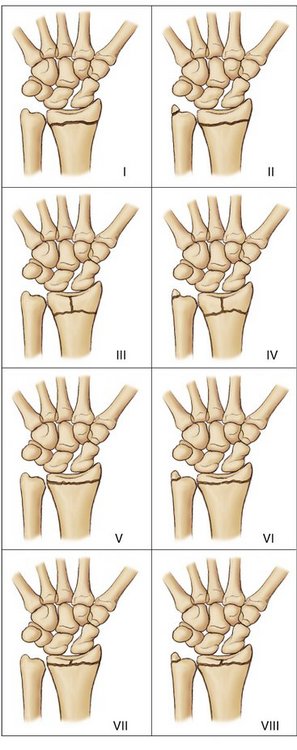

The Frykman classification was introduced in 1967. This classification system differed in that it addressed the radiocarpal joint and the radioulnar joint and presence or absence of an ulnar styloid fracture (Fig. 1-3).28

FIGURE 1-3 Frykman Classification.

(Adapted from Metz S: Comparison of different radiography systems in an experimental study for detection of forearm fractures and evaluation of the Muller-AO and Frykman classification for distal radius fractures. Invest Radiol 2006; 41:9.)

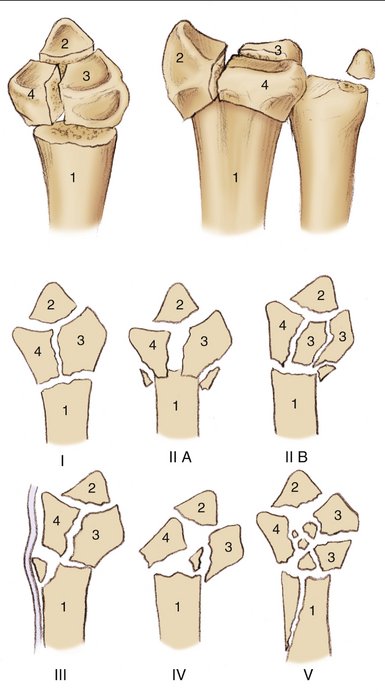

Melone29 in 1984 described distal radius fractures based on the following four components: shaft, radial styloid, dorsal medial facet, and volar medial facet. This classification system is used widely for defining indications and determining surgical approach, but its accuracy and reproducibility based on standard radiographs have not been determined (Fig. 1-4).

FIGURE 1-4 Melone Classification.

(Adapted from Melone CP Jr: Distal radius fractures: patterns of articular fragmentation. Orthop Clin North Am 1993; 24:221.)

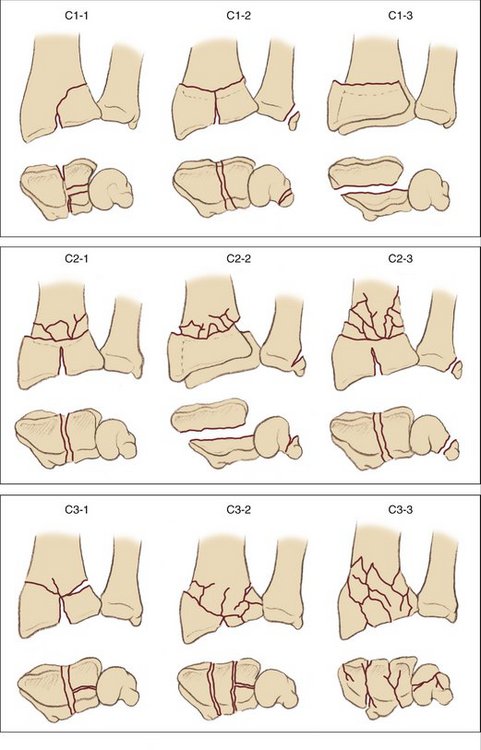

The AO/ASIF classification, used by Muller and associates30 to describe distal radius fractures, was published in 1987. Although there are 27 subtypes of distal radius fractures within this system, it has been shown to have the highest reliability when simplified into three categories—extra-articular, partial articular, and complete articular (Fig. 1-5).

FIGURE 1-5 AO Classification.

(Adapted from Metz S: Comparison of different radiography systems in an experimental study for detection of forearm fractures and evaluation of the Muller-AO and Frykman classification for distal radius fractures. Invest Radiol 2006; 41:9.)

In 1993, Cooney and colleagues31 from Mayo published their classification system, which was described as treatment based. It consists of four types, based on the degree and location of displacement (Table 1-3).32

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| I | Intra-articular fracture of the radiocarpal joint |

| II | Displaced intra-articular fracture of the radioscaphoid joint involving a significant portion of the articular surface of the distal radius (more than a radial styloid fracture) |

| III | Displaced intra-articular fracture of the radiolunate joint that often manifests as a “die-punch” fracture of the lunate fossa; a displaced fracture component into the distal radioulnar joint is common |

| IV | Displaced intra-articular fracture involving both radioscaphoid joint surfaces and usually involving the sigmoid fossa of the distal radioulnar joint; this fracture is usually comminuted |

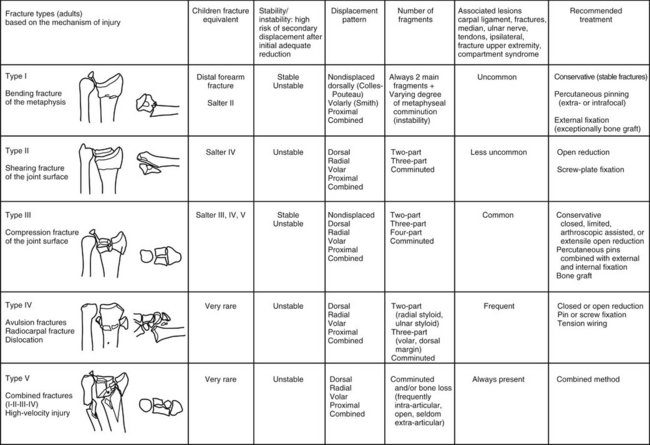

Ultimately, also in 1993, Fernandez33 published a modification of the AO/ASIF system, but based his classification on the mechanism of injury. According to the authors, this classification was developed to be practical, to suggest stable versus unstable fracture patterns, to include associated injuries, to identify pediatric fracture equivalents, and to suggest general recommendations for treatment (Fig. 1-6).

Evolution of Treatment

Splinting and Casting

“… while assistants hold the limb in a middle state between pronation and supination, let a thick and firm compress be applied transversely on the anterior surface of the limb, at the seat of the fracture, taking care that it shall not press on the ulna; let this be bound on firmly with a roller and then let a tin splint, formed to the shape of the arm, be applied to both its anterior and posterior surfaces.”9

Wheat glues, wax, and resins were used for many centuries to make bandages set hard; egg whites also were used, up until the 18th century in England. Gypsum (plaster of Paris) was being used for casting in Arabia, and was described by the British Consul in Bassora, Eton, in 1798. The use of plaster in splinting bandages seemed to increase in popularity in Europe in the 1850s after Mathijsen described them in a medical book that was promoted by a friend.9 Mathijsen used plaster bandages extensively during the Crimean War and applied them in a circumferential manner; however, he recommended splitting the cast while it was still wet to be able to loosen the cast without breaking it. He attributed to his plaster bandages the following characteristics: simplicity, easy application, quick application, instant setting, complete fixation, removability, exact retention, porosity, resilience (“neither urine, nor pus nor water harm its firmness or strength in any way”), and affordability.9 Around the same time, Pirogoff, in Russia, independently advocated casting fractures in plaster bandages; St. John, an American, strongly supported the use of plaster bandages, but also introduced the concept of cast padding. Although the word of plaster casting spread out of the Crimean War, it was not until World War I that the use of plaster casts really became popular.9

Surgical Treatment

The factors leading to the emergence of safe, successful surgery for the treatment of fractures of the distal radius are multifactorial, and their respective influence is interrelated and complicated. In its simplest terms, the development of anesthesia and asepsis were the major strides leading to safe surgical techniques. Priestley discovered nitrous oxide in 1772. Ether was used in a demonstration at Massachusetts General Hospital in 1846, and its use became popularized in America and Europe. Lister championed antiseptic principles and published results in 1867. Until the invention of boilers by Neuber (1885) and steam sterilizers, however, Lister’s principles were not widely accepted, and surgery remained a dangerous endeavor, with a high rate of morbidity and mortality.9

Treatments other than casting or splinting for distal radius fractures were initially described around 1930.34 Anderson and O’Neil35 in 1944 used a simple external fixator to treat distal radius fractures. Pins were placed proximally in the radius and distally in the second metacarpal and attached by a simple bar. Advances in this technique led to many other designs of external fixators over the decades, and external fixation remains a viable treatment option in severely comminuted or open distal radius fractures. Such advances include fixators that are radiolucent and have adjustable bars. Nonbridging external fixation affords the benefit of not spanning the radiocarpal joint, minimizing the sequelae of external fixation on overall wrist motion.

Percutaneous pinning was introduced early in the timeline of surgical treatment of distal radius fractures and has endured in various forms to the present day. Lambotte described the placement of a single pin into the radial styloid to stabilize a displaced distal radius fracture in 1908. This technique was modified by Stein and Katz in 1975 with the addition of a pin through a dorsal-ulnar radial fragment, from proximal to distal; Uhl, Lortat-Jacob, and Mortier all described in 1976 radial styloid pinning plus fixation of the posteromedial fragment with an ulnar-radial pin. Most notably, Kapandji introduced the concept of intrafocal pinning in 1976. Two pins, 0.078 inch in size, are placed directly into the fracture site and then driven proximally into the radial diaphysis, buttressing the fracture site. Kapandji later modified his description of this technique to include a third pin. This intrafocal pinning has been extensively studied and is arguably the most published percutaneous technique. It is still used extensively, especially in Europe.36

Open reduction and internal fixation of distal radius fractures was described well after the first description of percutaneous pinning or external fixation. Ellis37 described the use of a volar buttress plate for Barton’s fractures in 1965, but it was not until the 1980s and 1990s that the role of internal fixation in the surgical armamentarium of distal radius fractures began to grow. Concurrently, increased focus on outcome studies better defined which fracture patterns did not do as well with prior treatment methods. Similarly, outcome studies and biomechanical studies showed the importance of restoration of radial length, radial inclination, articular congruity, and palmar tilt.

More recently, advances have been made in implant technology and surgical techniques that continue to advance the treatment of distal radius fractures. Specifically, these advances have improved our ability to address severely comminuted, intra-articular fractures that would previously have been less optimally treated.38,39

The realization that the balance between achieving anatomical reduction with stable fixation and allowing early mobilization with rehabilitation was important has encouraged the popularity of open reduction and internal fixation with fragment-specific fixation type devices. This concept was popularized by Medoff and Kopylov40 and has permeated throughout the development of new technology. Additionally, the use of arthroscopy (credited to Takagi, Watanabe, and Jackson in the knee) in the wrist for arthroscopically assisted management of distal radius fractures is a more recently introduced idea, useful especially in cases of complex intra-articular fractures.41,42

Past, Present and Future

Distal radius fractures have remained one of the most common fractures seen by physicians since the time of Hippocrates. Much has changed since that time, however. Not only has the nature of the injury changed with the increasing frequency of higher energy trauma, but also patients, their expectations, and the tools available for treatment and evaluation of success of that treatment all have undergone significant metamorphoses. At the time Colles published his article, the life expectancy for a laborer was a mere 23 years, there was no electricity, and surgery was thought to expose a patient to “more chances of death than the English soldier on the field of Waterloo.”9 Clearly, things have changed, and continue to evolve. Rang9 described five stages of knowledge:

Rang used polio as an example in The Story of Orthopaedics.9 In the context of distal radius fractures, we currently exist between the third and fourth stage. The coming decades will undoubtedly bring more effective treatments and a focus on prevention, including targeting osteoporosis and insufficiency fractures and high-energy accidents and injuries. The history of distal radius fractures has brought us to where we are in their diagnosis and treatment today, and we will certainly see improvements continue to evolve as we move forward.

1. Colles A. On the fracture of the carpal extremity of the radius. Edinburgh Med Surg J. 1814;10:182.

2. Petit JL. L’Art de guerir les maladies des os. Paris: L. d’Houry; 1705.

3. Pouteau C. Oeuveres posthumes de M. Pouteau: memoire, contenant quelques reflexions sur quelques fractures de l’avant-bras, sur les luxations incompletes du poignet et sur le diastasis. Paris: PhD Pierres; 1783.

4. Peltier LF. Fractures of the distal end of the radius: an historical account. Clin Orthop. 1984;187:18-21.

5. Dupuytren G. On the injuries and diseases of bones, being selections from the collected edition of the clinical lectures of Baron Dupuytren (trans. and ed.) Clark F. LeGros; 1847, Syndenham Society: London.

6. Goyrand G. Memoirs sur les fractures de l’extremite inferieure de radius, qui simulent les luxations du poignet. Gazette de Medicine. 1832;3:664.

7. Goyrand G. De la fracture par contre-coup de l’extremite inferieure du radius. Journal Hebdomadaire. 1836;1:161.

8. Nelaton A. Elements de pathologie chirurgicale. Paris: Germer Bailliere; 1844.

9. Rang M. The Story of Orthopaedics. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1966.

10. Smith RW. A treatise on fractures in the vicinity of joints and on certain forms of accidental and congenital dislocations. Dublin: Hodges & Smith; 1847.

11. Beck C. Colles’ fracture and the Roentgen-rays. Med News. 1898;72:230.

12. Cotton FJ: Experimental Colles’ fracture. J Boston Soc Med Sci 1897-1898; 2:171.

13. Cotton FJ. A study of the x-ray plates of one hundred and forty cases of fracture of the lower end of the radius. Boston Med Surg J. 1900;143:305.

14. Cotton FJ. The pathology of fracture of the lower extremity of the radius. Ann Surg. 1900;32:194-218. 388-415

15. Morton R. A radiographic survey of 170 cases clinically diagnosed as “Colles’ fracture.”. Lancet. 1907;1:731.

16. Pilcher LS. Fractures of the lower extremity or base of the radius. Ann Surg. 1917;65:1.

17. Destot E. Injuries of the Wrist, a Radiological Study. New York: Paul B. Hoeber; 1926.

18. Burstein AH. Fracture classification systems: do they work and are they useful? J Bone Joint Surg. 1993;75:1743-1744.

19. Nissen-Lie HS. Fracture radii “typical.”. Nord Med. 1939;1:293-303.

20. Gartland JJ, Werley CW. Evaluation of healed Colles’ fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1951;33:895-907.

21. Lidstrom A. Fractures of the distal end of the radius: a clinical and statistical study of end results. Acta Orthop Scand. 1959;30:1-118.

22. Older TM, Stabler GV, Cassebaum WH. Colles’ fracture: evaluation and selection of therapy. J Trauma. 1965;5:469-474.

23. Axelrod T, Paley D, Green J, et al. Limited open reduction of the lunate facet in comminuted intra-articular fractures of the distal radius. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1988;13:372-377.

24. Bartosh RA, Saldana MJ. Intra-articular fractures of the distal radius: a cadaveric study to determine if ligamentotaxis restores radiopalmar tilt. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1990;15:18-21.

25. Bradway JK, Amadio PC, Cooney WP. Open reduction and internal fixation of displaced, comminuted intra-articular fractures of the distal end of the radius. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71:839-847.

26. Putnam MD, Seitz WH. Fractures of the distal radius. Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults, 5th ed; 2002, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia.

27. Rikli DA, Regazzoni P. Fractures of the distal end of the radius treated by internal fixation and early function: a preliminary report of 20 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78:588-592.

28. Frykman G. Fractures of the distal radius, including sequelae—shoulder- and finger-syndrome, disturbance in the distal radioulnar joint and impairment of nerve function: a clinical and experimental study. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1967;108:1-153.

29. Melone CPJr. Articular fractures of the distal radius. Orthop Clin North Am. 1984;15:217-236.

30. Muller ME, Nazarian S, Koch P, et al. The Comprehensive Classification of Long Bones. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1990. pp 54-63

31. Cooney WP. Fractures of the distal radius: a modern treatment-based classification. Orthop Clin North Am. 1993;24:211-216.

32. Jupiter JB, Fernandez FL. Comparative classification for fractures of the distal end of the radius. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1997;22:563-571.

33. Fernandez DL. Fractures of the distal radius: operative treatment. Instr Course Lect. 1993;42:73-88.

34. Bohler L:. Treatment of Fractures, 4th ed. Baltimore: William Wood; 1929.

35. Anderson R, O’Neil G. Comminuted fractures of the distal end of the radius. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1944;78:434-440.

36. Rayhack JM: The history and evolution of percutaneous pinning of displaced distal radius fractures. Orthop Clin North Am 1993; 24:287-300.

37. Ellis J. Smith’s and Barton’s fractures: a method of treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1965;47:724-727.

38. Nana AD, Joshi A, Lichtman DM. Plating of the distal radius. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13:159-171.

39. Smith DW, Henry MH. Volar fixed-angle plating of the distal radius. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13:28-36.

40. Medoff RJ, Kopylov P. Open reduction and immediate motion of intraarticular distal radius fractures with a fragment specific system. Arch Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1999;2:53.

41. Benson LS, Minihane KP, Stern LD, et al. The outcome of intra-articular distal radius fractures treated with fragment-specific fixation. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2006;31:1333-1339.

42. Wiesler ER, Chloros GD, Mahirogullari M, et al. Arthroscopic management of distal radius fractures. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2006;31:1516-1526.