51 Disorders of White Blood Cells

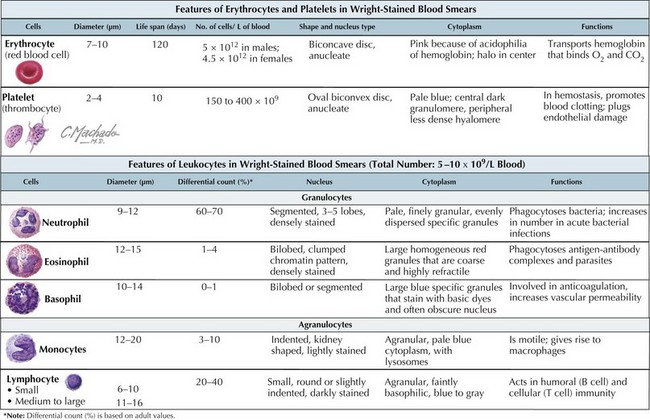

White blood cells (WBCs), or leukocytes, are an integral part of the host immune system. Their microscopic appearance after Wright-staining categorizes them as either granulocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils) or agranulocytes (monocytes, macrophages, and lymphocytes). Each WBC has a specific function within the immune system (Figure 51-1).

Etiology and Pathogenesis

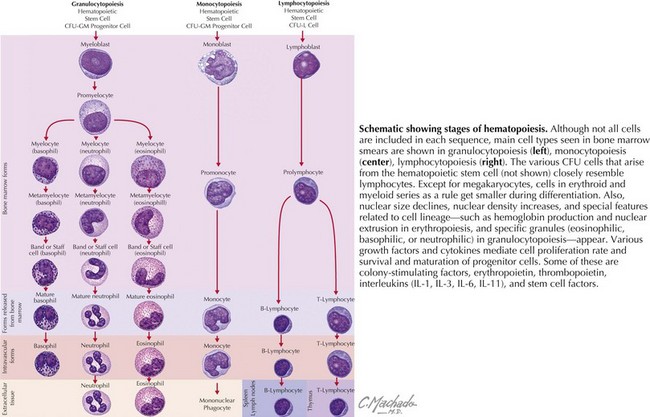

WBCs derive from hematopoietic progenitor cells in the bone marrow (Figure 51-2). Their maturation is induced by colony-stimulating factors.

This chapter focuses on congenital and acquired neutrophil disorders with a brief discussion regarding disorders of eosinophils, basophils, and monocytes. Disorders of lymphocytes, part of the body’s acquired (adaptive) immunity, are discussed in the immunology section (see Chapter 21).

Clinical Presentation and Differential Diagnosis

Congenital Disorders of Neutrophils

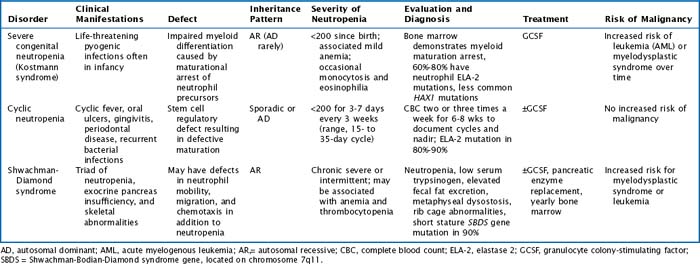

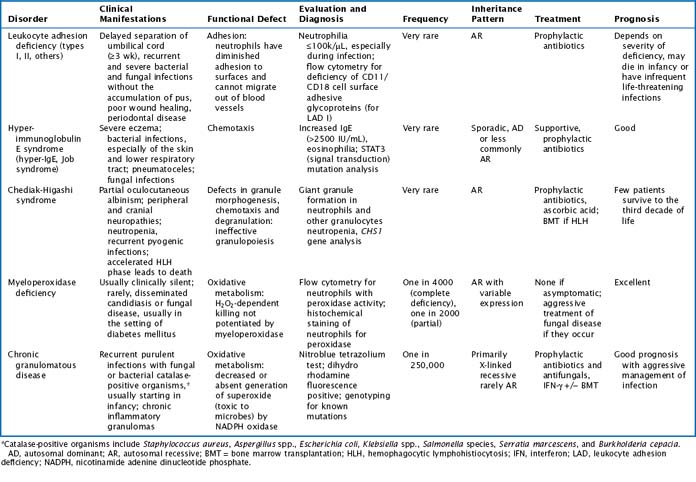

There are multiple congenital neutropenias that are being further categorized as knowledge of the genetic basis of disease improves (Tables 51-1 and 51-2). These congenital disorders are exceedingly rare.

Table 51-2 Additional Congenital Disorders Associated with Neutropenia

| Disorder | Clinical Manifestations |

|---|---|

| Cartilage-hair hypoplasia | Short limbs, dwarfism, abnormally fine hair |

| Myelokathexis with dysmyelopoiesis | Marrow retention of neutrophils, recurrent bronchopulmonary infections |

| Dyskeratosis congenita | Bone marrow failure syndrome; dystrophic changes in nails, skin (hyperpigmentation), and mucous membranes (leukoplakia) |

| Fanconi anemia | Bone marrow failure syndrome; GU and skeletal abnormalities, increased chromosome fragility |

| Organic acidemias (propionic, methylmalonic) | Initially well at birth, then toxic encephalopathy |

| Osteopetrosis | Defective bone turnover with resultant hematopoietic insufficiency and bone fragility |

| Reticular dysgenesis (congenital aleukocytosis) | Absent WBC, hypogammaglobulinemia, thymic hypoplasia, severe infection and death in infancy |

| Immunodeficiencies (severe combined immunodeficiency, common variable immunodeficiency, hyper-IgM) | Frequent infections, failure to thrive, hepatosplenomegaly |

| Glycogen storage disease type 1b (von Gierke disease) and other inborn errors of metabolism | Neutropenia and functional neutrophil defect, hepatosplenomegaly |

GU, genitourinary; WBC, white blood cell.

Acquired Disorders of Neutrophils

Drug-Induced Neutropenia

Cytotoxic agents for the treatment of malignancies are known to cause severe neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. Other more routine medications may be implicated in causing neutropenia (Table 51-4). Neutropenia is caused either by decreasing bone marrow synthesis or by evoking production of antineutrophil antibodies. Spontaneous resolution typically occurs after discontinuation of the offending drug.

| Drug Class | Drugs |

|---|---|

| Antimicrobials | Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, sulfonamides, macrolides, vancomycin, cephalosporins, semisynthetic penicillins (vancomycin), quinine, chloroquine, amphotericin B |

| Antiinflammatory drugs | NSAIDs (ibuprofen, others) |

| Psychotropic drugs | Clozapine, phenytoin |

| Gastrointestinal drugs | Histamine H2 receptor antagonists (ranitidine) |

| Antithyroid drugs | Methimazole, propylthiouracil |

| Cardiovascular | Antiarrhythmics, diuretics |

| Toxins | Benzene |

| Chemotherapeutic agents | Cytotoxic drugs |

NSAID, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug.

* This is a partial list only of the more commonly prescribed medications for children.

Other Causes of Acquired Neutropenia

Malignancies and marrow infiltrative processes do not usually cause an isolated neutropenia; multiple cell lines are more commonly affected (Table 51-5). Additionally, splenomegaly affects all cell lines because blood products get trapped in the enlarged spleen.

| Malignancies and bone marrow failure | Leukemia, lymphoma, preleukemic states, myelodysplastic syndromes, aplastic anemia |

| Nutritional deficiency | Vitamin B12, folate, copper or starvation |

| Other | Splenomegaly, complement activation (e.g., hemodialysis) |

Leukocytosis

Neutrophilia

An elevated neutrophil count can result from increased bone marrow production, increased movement of neutrophils out of the marrow and into the circulation, or possibly from decreased peripheral destruction if the spleen is not functioning. There are many causes of neutrophilia, some acute and some chronic in nature (Table 51-6).

| Infectious | Bacterial and viral |

| Rheumatologic | JIA, Kawasaki disease |

| Asplenia | Surgical or functional |

| Gastrointestinal | Liver failure, IBD |

| Endocrine | Diabetic ketoacidosis |

| Neutrophil function disorders | CGD, LAD (see Neutrophil Function Defects above) |

| Drugs | Corticosteroids (release neutrophils from marrow, slow egress from circulation into tissues, postpone apoptotic cell death), epinephrine (release of the marginating pool into circulation) |

| Stressors | Shock, trauma, emotional, burns, surgery, hemorrhage, hypoxia |

| Malignancy | Clonal expansion, especially if WBC >100,000/µL; leukemia, myeloproliferative disorders (note H&P, other cell lines, peripheral blasts) |

| Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) | Defective proliferation and maturation of myeloid cells |

CGD, chronic granulomatous disease; H&P, history and physical; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; JIA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis; LAD, leukocyte adhesion deficiency; WBC, white blood cell.

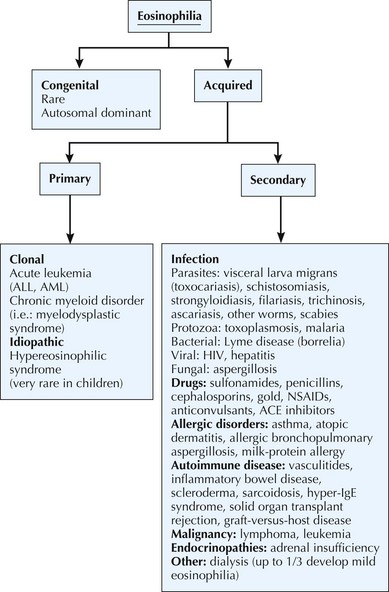

Eosinophilia

Eosinophils have a role in both immunoenhancing and suppressive functions. They are very efficient in the destruction of invasive metazoan parasites, and they inactivate inflammatory mediators in immediate hypersensitivity reactions. Eosinophilia is characterized by the total eosinophil count. Mild eosinophilia, with an absolute count 600 to 1500/µL, is fairly common and usually transient. It most frequently results from allergies and resolves with control of the underlying disease process. Moderately severe eosinophilia is defined as an absolute count of 1500 to 5000/µL. Severe eosinophilia is greater than 5000/µL with the most common reason being visceral larva migrans (toxocariasis). The cause of eosinophilia is diverse; a history of fever, allergies, atopy, asthma, recent travel, diarrhea, environmental exposures, medication, or exposure to pets may help differentiate causes of eosinophilia (Figure 51-3).

Kyono W, Coates TD. A practical approach to neutrophil disorders. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2002;49(5):929.

Lekstrom-Himes JA, Gallin JI. Immunodeficiency caused by defects in phagocytes. N Engl J Med. 2002;343(23):1703.

Schwartzberg LS. Neutropenia: etiology and pathogenesis. Clin Cornerstone. 2006;8(suppl 5):S5.

Segel GB, Halterman JS. Neutropenia in pediatric practice. Pediatr Rev. 2008;29:12-24.

Serwint JR, Dias MM, Chang H, et al. Outcomes of febrile children presumed to be immunocompetent who present with leukopenia or neutropenia to an ambulatory setting. Clin Pediatr. 2006;44(7):593.