Chapter 621 Disorders of the Uveal Tract

Uveitis (Iritis, Cyclitis, Chorioretinitis)

The uveal tract (the inner vascular coat of the eye, consisting of the iris, ciliary body, and choroid) is subject to inflammatory involvement in a number of systemic diseases, both infectious and noninfectious, and in response to exogenous factors, including trauma and toxic agents (Table 621-1). Inflammation may affect any 1 portion of the uveal tract preferentially or all parts together.

Table 621-1 UVEITIS IN CHILDHOOD

ANTERIOR UVEITIS

POSTERIOR UVEITIS (CHOROIDITIS—MAY INVOLVE RETINA)

ANTERIOR AND/OR POSTERIOR UVEITIS

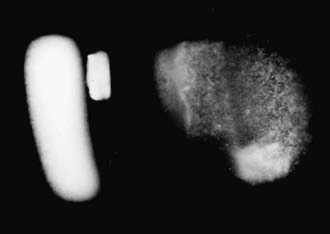

Iritis may occur alone or in conjunction with inflammation of the ciliary body as iridocyclitis or in association with pars planitis. Pain, photophobia, and lacrimation are the characteristic symptoms of acute anterior uveitis, but the inflammation may develop insidiously without disturbing symptoms. Signs of anterior uveitis include conjunctival hyperemia, particularly in the perilimbal region (ciliary flush), and cells and protein (“flare”) in the aqueous humor (Fig. 621-1). Inflammatory deposits on the posterior surface of the cornea (keratic precipitates) and congestion of the iris may also be seen. More chronic cases may show degenerative changes of the cornea (band keratopathy), lenticular opacities (cataract), development of glaucoma, and impairment of vision. The cause of anterior uveitis is often obscure; primary considerations in children are rheumatoid disease, particularly pauciarticular rheumatoid arthritis, Kawasaki disease, reactive arthritis (postinfectious), and sarcoidosis. Iritis may be secondary to corneal disease, such as herpetic keratitis or a bacterial or fungal corneal ulcer, or to a corneal abrasion or foreign body. Traumatic iritis and iridocyclitis are especially common in children.

Figure 621-1 Cell and flare in the anterior chamber. The flare represents protein leakage.

(Courtesy of Peter Buch, CRA.)

Table 621-2 has been developed by the American Academy of Pediatrics for children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis without known iridocyclitis.

Table 621-2 EXAMINATION SCHEDULE FOR CHILDREN WITH JRA WITHOUT KNOWN IRIDOCYCLITIS

| JRA SUBTYPE | AGE AT ONSET | |

|---|---|---|

| <7 Years | ≥7 Years | |

| PAUCIARTICULAR | ||

| Positive ANA | ||

| Less than 4 years’ duration | Every 3-4 mo | Every 6 mo |

| 4-7 years duration | Every 6 mo | Annually |

| More than 7 years’ duration | Annually | Annually |

| Negative ANA | ||

| Less than 4 years’ duration | Every 6 mo | Every 6 mo |

| 4-7 years duration | Every 6 mo | Annually |

| More than 7 years’ duration | Annually | Annually |

| POLYARTICULAR | ||

| Positive ANA | ||

| Less than 4 years’ duration | Every 3-4 mo | Every 6 mo |

| 4-7 years duration | Every 6 mo | Annually |

| More than 7 years’ duration | Annually | Annually |

| Negative ANA | ||

| Less than 4 years’ duration | Every 6 mo | Every 6 mo |

| 4-7 years duration | Every 6 mo | Annually |

| More than 7 years’ duration | Annually | Annually |

| SYSTEMIC | Annually, regardless of duration | Annually, regardless of duration |

ANA, antinuclear antibody; JRA, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.

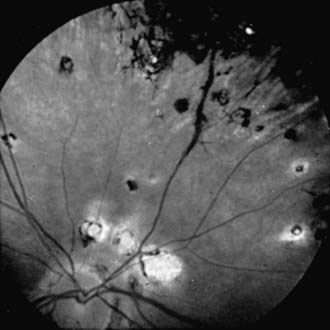

Choroiditis, inflammation of the posterior portion of the uveal tract, invariably also involves the retina; when both are obviously affected, the condition is termed chorioretinitis. The causes of posterior uveitis are numerous; the more common are toxoplasmosis, histoplasmosis, cytomegalic inclusion disease, sarcoidosis, syphilis, tuberculosis, and toxocariasis (Fig. 621-2). Depending on the etiology, the inflammatory signs may be diffuse or focal. Vitreous reaction often occurs as well. With many types, the result is atrophic chorioretinal scarring demarcated by pigmentation, often with visual impairment. Secondary complications include retinal detachment, glaucoma, and phthisis.

BenEzra D, Cohen E. Cataract surgery in children with chronic uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1255-1260.

Chu DS, Foster CS. Sympathetic ophthalmia. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2002;42:179-185.

Cunningham ETJr, Suhler EB. Childhood uveitis-young patients, old problems, new perspectives. J AAPOS. 2008;12:537-538.

1993 Adapted from American Academy of Pediatrics, Sections on Rheumatology and Ophthalmology: guidelines for ophthalmic examinations in children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Pediatrics. 1993;92:295-296.

Guly C, Forrester JV. Investigation and management of uveitis. BMJ. 2010;341:c4976.

Holland GN, Stiehm ER. Special considerations in the evaluation and management of uveitis in children. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135:867-878.

Kadayifcilar S, Eldem B, Tumer B. Uveitis in childhood. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2003;40:335-340.

Kotaniemi K, Savolainen A, Karma A, et al. Recent advances in uveitis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48:489-502.

McCluskey P, Powell RJ. The eye in systemic inflammatory diseases. Lancet. 2004;364:2125-2133.

Oren B, Sehgal A, Simon JW, et al. The prevalence of uveitis in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J AAPOS. 2001;5:2-4.

Patel H, Goldstein D. Pediatric uveitis. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2003;50:125-136.

Rosenberg KD, Feuer WJ, Davis JL. Ocular complications of pediatric uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:2299-2306.

Smith JA, Mackensen F, Sen HN, et al. Epidemiology and course of disease in childhood uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:1544-1551.