Disorders of the thyroid and parathyroid glands

Thyroid disorders

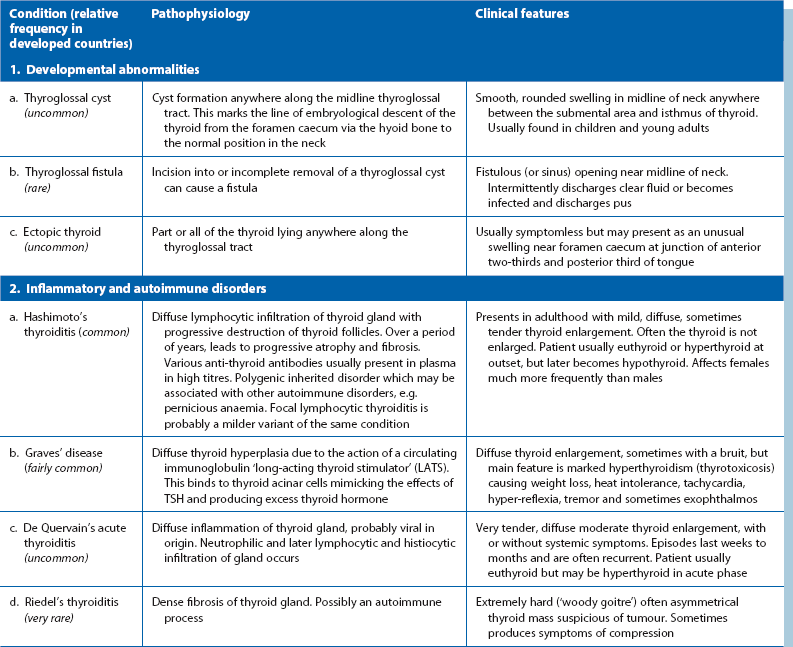

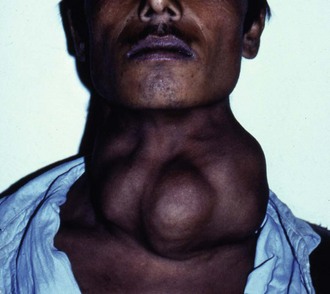

Pathophysiological and clinical features of the various disorders are summarised in Table 49.1, except for thyroid malignancy, outlined later in Table 49.2.

Main clinical presentations of thyroid disease in surgical practice

Diffuse or generalised enlargement of the thyroid

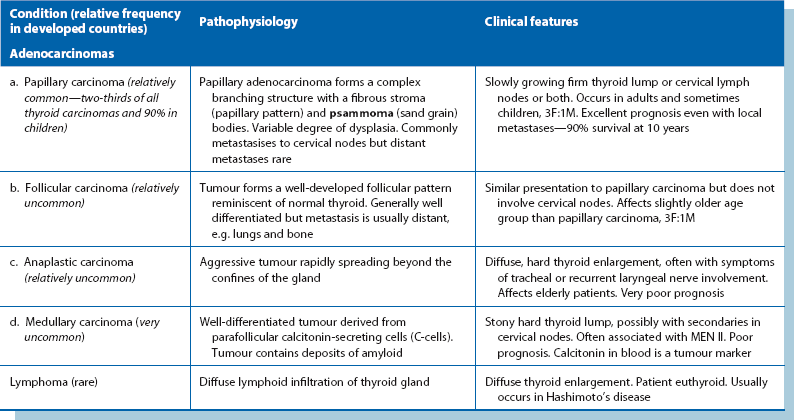

Iodine deficiency is the usual cause of endemic goitres (often in isolated, mountainous regions such as Nepal), preventable by adding iodine to the diet. These are often asymmetrical, soft and composed of hyperplastic nodules, and can reach enormous sizes (see Fig. 49.1). Although unsightly, endemic goitres cause surprisingly few symptoms and the patient is usually euthyroid.

Anaplastic carcinomas may cause thyroid swellings in elderly patients (see Fig. 49.2), usually with symptoms of invasion including hoarseness (recurrent laryngeal nerve), and stridor, particularly at night, with tracheal invasion. The gland is hard on palpation. The uncommon thyroid lymphomas also present with diffuse enlargement.

Solitary thyroid nodule

A clinically solitary thyroid nodule is common but 50% are multinodular on imaging (Fig. 49.3). When small, these nodules are found incidentally, often noticed when the patient swallows. Less than 10% of true solitary nodules are malignant although this rises to about 40% after neck irradiation. Almost all thyroid nodules in childhood are malignant. Fallout from the Chernobyl nuclear meltdown caused many thyroid cancers in children. Malignancy should be excluded in any solitary nodule, and FNA cytology or core needle biopsy is the first step.

Other features associated with thyroid enlargement

A new area of enlargement in an existing goitre may result from haemorrhage into a cyst or nodule, enlargement of a hyperplastic nodule or a developing carcinoma. If the gland extends into the anterior mediastinum behind the sternum (see Fig. 49.6, below), the trachea may be compressed or displaced by this retrosternal goitre and cause stridor, often only obvious when the neck is in certain positions, for example, sleeping on one side. Hoarseness or stridor may also result from invasion of trachea or recurrent laryngeal nerve by anaplastic carcinoma.

Hyperthyroidism

Clinical manifestations of hyperthyroidism are summarised in Box 49.1 (see also Fig. 49.4). Excessive thyroid hormone is a feature of Graves’ disease. Mild hyperthyroidism also occurs in the early stages of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, burning out later with the patient becoming hypothyroid. A solitary adenomatous nodule may produce excess thyroid hormone causing hyperthyroidism. This is known as a toxic or hot nodule.

Special points in examining a thyroid swelling

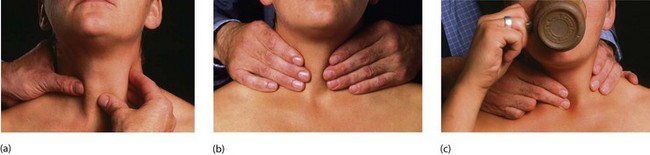

The patient should be seated in a chair (Fig. 49.5) with space to palpate from behind and have a glass of water available to swallow. General examination should look for signs of hyperthyroidism (tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, fine tremor, sweaty palms and hyper-reflexia) and for signs specific to Graves’ disease (exophthalmos and ophthalmoplegia). Next, the front of the neck is inspected while the patient swallows; the characteristic rise of a thyroid swelling results from its investment in pretracheal fascia attached to the larynx above. A normal thyroid is not visible even on swallowing, and is not normally palpable.

Fig. 49.5 Examination of the thyroid gland

The patient should be sitting upright in a chair with room for the examiner to approach from behind. (a) Gentle palpation from the front with slight sideways pressure from the left hand whilst palpating with the right. This is repeated for the right side of the gland. (b) General palpation of the gland from behind. Is there enlargement? Is it a single nodule or multinodular? How big is it? (c) Palpation of the gland while the patient swallows. Does the gland rise with swallowing? Is there retrosternal extension?

Approach to investigation of a thyroid mass

The questions during investigation are summarised in Box 49.2 and described in detail below. Patients who have undergone previous neck radiotherapy should be considered at high risk of thyroid carcinoma.

Morphology of the gland

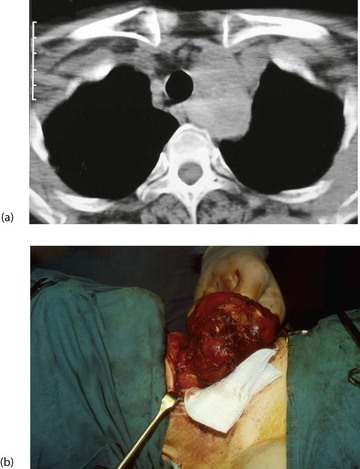

Ultrasound scanning is useful to establish morphology and diagnose cysts. It can also indicate retrosternal extension. CT scans of neck and thoracic outlet are taken if malignancy is suspected or if there appears to be tracheal displacement or compression (Figs 49.6).

Functional activity of glandular tissue

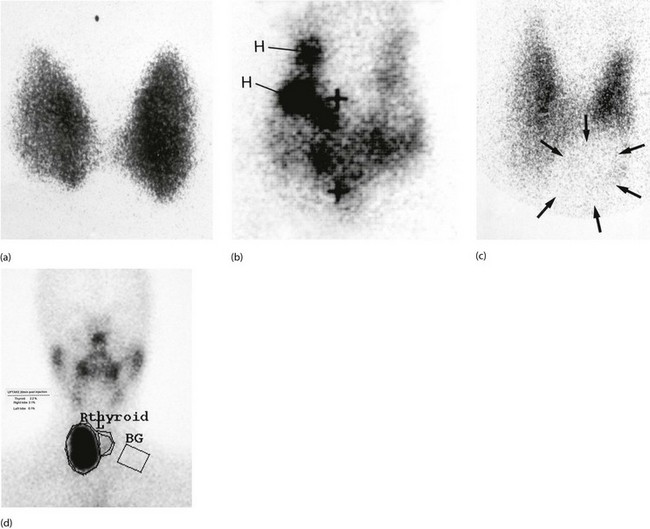

• Diffuse, homogeneous uptake—found in normal glands or in diffuse hyperactivity, e.g. Graves’ disease

• Generalised but patchy uptake—in multinodular goitre where hyperplastic nodules are less active than the surrounding normal tissue

• The cold nodule—an area devoid of uptake indicates non-secreting tissue, i.e. tumour, inactive adenomatous nodule or cyst and requires tissue diagnosis

• The hot nodule—or toxic adenoma. This represents an autonomous focus of excess T4 secretion. Secretory activity of the thyroid is suppressed. The patient is usually euthyroid but sometimes thyrotoxic (‘toxic nodule’)

Very occasionally, thyroid malignancies secrete thyroid hormones and show up as warm or hot nodules on isotope scanning. Isotope scanning can also identify and localise ectopic thyroid tissue (in the tongue or along the course of the thyroglossal duct), retrosternal extension of a thyroid swelling and metastases of functioning thyroid carcinomas, provided the thyroid has been removed or ablated.

Specific clinical problems of the thyroid and their management

Hyperthyroidism (thyrotoxicosis)

Treatment of hyperthyroidism: There are three main options: anti-thyroid drugs, radioisotope destruction of functioning thyroid tissue and subtotal (or total) thyroidectomy. Anti-thyroid drugs are the first-line except in the elderly and unfit; also patients with arrhythmias, angina and osteoporosis are usually treated with radioiodine from the outset. A randomised trial of all three treatments showed that of those treated with drugs, 34% developed recurrent hyperthyroidism. In the radioiodine group, half needed more than one dose but all became hypothyroid within a year. In those treated surgically, 8% recurred and needed further therapy. All groups reported 95% satisfaction with no differences in quality of life.

Thyrotoxic eye disease: Half of thyrotoxic patients develop eye signs known as thyrotoxic ophthalmopathy which can arise or regress independently of thyroid function. Eye disease does not occur in multinodular or adenoma thyrotoxicity. Eye disorders range from minor inflammation of conjunctiva with mild prominence of the globe to severe, debilitating and disfiguring eye disease that occurs in 3–5% of thyrotoxic patients.

Radioactive iodide therapy: Radioactive iodide (131I or 125I) is given by mouth as capsules or solution in doses 100 times higher than for diagnostic scanning (see Fig. 49.7). This is appropriate for middle-aged or elderly patients but is contraindicated in pregnancy because of the risk of fetal thyroid damage and genetic disruption. Iodide is avidly taken up by the gland, and beta particle emission destroys the most active thyroid tissue over a period of weeks or months. Note that anti-thyroid drugs usually need to continue until radioiodine achieves its greatest effect. After treatment, the rest of the isotope is excreted via the kidney, faeces, sweat, saliva and breath. Gamma rays are emitted from the patient’s body and may be absorbed by others nearby. Patients should avoid pregnancy for 6 months afterwards.

Fig. 49.7 Radioisotope thyroid scans

(a) This enlarged thyroid shows homogeneous tracer uptake typical of a simple colloid goitre. (b) Heterogeneous tracer uptake in a multinodular colloid goitre. The dark areas H are ‘hot nodules’; to maintain the euthyroid state, the rest of the gland exhibits diminished uptake. The + signs indicate the positions of the thyroid cartilage and the suprasternal notch. (c) Solitary ‘cold’ thyroid nodule. The area of low uptake (outline arrowed) at the lower left pole of the thyroid corresponds with a palpable nodule. In the case of a solid lesion (as confirmed by ultrasound), a cold nodule may indicate malignancy. (d) Solitary ‘hot’ thyroid nodule. The area of high uptake in the lower part of the right lobe corresponds to a palpable mass. This patient was hyperthyroid and the lesion could be described as a ‘toxic nodule’. Activity of the rest of the gland is suppressed by pituitary-mediated negative feedback from the high serum thyroxine level. The rectangle marked BG measures the background radiation in order to quantify the thyroid uptake

Anti-thyroid drugs: Most thyrotoxicosis patients are initially managed with anti-thyroid drugs to block hormone synthesis. This treatment is not suitable for nodular toxicity because hyperactivity inevitably recurs. Carbimazole is the most popular drug and is generally well tolerated. Carbimazole restores plasma hormone levels to normal over 4–8 weeks and treatment is continued for 12–18 months. Unfortunately, hyperthyroidism recurs in about half within 2 years. Between 5% and 10% develop a rash and there are rare cases of agranulocytosis, usually reversible. The white blood count should be monitored during treatment; a sore throat or other infection should alert the patient and doctor to this possible complication. Propylthiouracil is an effective anti-thyroid drug without these side-effects but poor control, frequent relapses, other side-effects and non-compliance lead to eventual referral for definitive treatment in up to 40%. In unstable patients with hypothyroidism alternating with hyperthyroidism, a block and replace regimen may succeed. Patients are given a higher dose of carbimazole to completely block thyroid hormone production, together with a standard replacement dose of thyroxine.

Indications for surgery: Surgery for thyrotoxicosis may be indicated as follows:

• When a quick and effective cure is desired that avoids long-term drug therapy. It is often the best treatment for Graves’ disease, particularly in younger patients, where the disease is unlikely to burn itself out for years

• When anti-thyroid drugs have proved unsatisfactory and radioiodide treatment is unsuitable

• In toxic multinodular goitre. Response to drug treatment is variable, and surgery also deals with the cosmetic deformity

• Toxic solitary nodules (‘hot nodules’) may be best excised to allow the suppressed normal thyroid to recover

Preoperative assessment and management of thyrotoxicosis: For all thyroid operations, preoperative assessment often includes laryngoscopy to demonstrate vocal cord function. This evaluates recurrent laryngeal nerve function should there be a question of operative damage later. Even without demonstrable cord damage, there is often a subtle change in voice quality after thyroidectomy, sometimes due to external laryngeal nerve damage. Patients should be warned of this before operation, especially if they are singers or politicians!

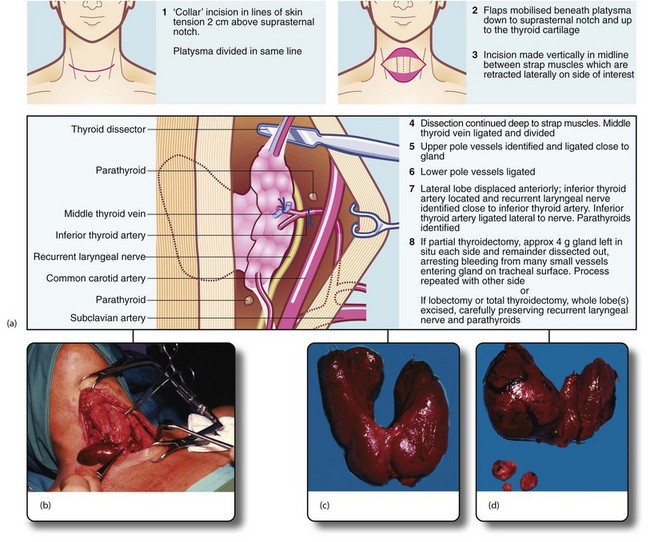

Subtotal thyroidectomy: Surgery (Fig. 49.8) for hyperthyroidism aims to remove enough thyroid tissue to render the patient euthyroid whilst preserving enough to prevent hypothyroidism. For Graves’ disease or toxic multinodular goitre, about 5–8 g of the gland is left intact. The technique of subtotal thyroidectomy leaves the posterior rim of each lobe in situ, minimising the risk of parathyroid or recurrent laryngeal damage. However, the risk of permanent hypoparathyroidism is 1–4% and of permanent recurrent laryngeal nerve damage 1–5%. Patients need to be warned of these risks before giving their consent to operation. A low transverse collar incision along a skin crease gives the best cosmetic result. Meticulous care is required in ligating the inferior thyroid artery (after identifying the recurrent laryngeal nerve) and the upper pole vessels. Primary or reactionary haemorrhage is a serious complication causing major blood loss and laryngeal compression. To avoid suffocation from a postoperative bleed, instruments for emergency reopening of the wound should be kept at the patient’s bedside after operation. The potential complications of thyroidectomy are summarised in Box 49.3.

Fig. 49.8 Thyroid and parathyroid operations

(a) The drawings show the standard neck exploration approach to thyroid and parathyroid operations, and the structures at particular danger—the recurrent laryngeal nerve and parathyroid glands. In the photographs, (b) shows neck exploration for hyperparathyroidism. A collar incision has been made and upper and lower flaps are held apart with the specially designed Joll’s retractor. A single large parathyroid adenoma is clearly visible. (c) Subtotal thyroidectomy specimen after operation for hyperthyroidism. (d) Total thyroidectomy specimen after operation for right-sided medullary carcinoma. Involved lymph nodes were ‘cherry picked’ and are also shown

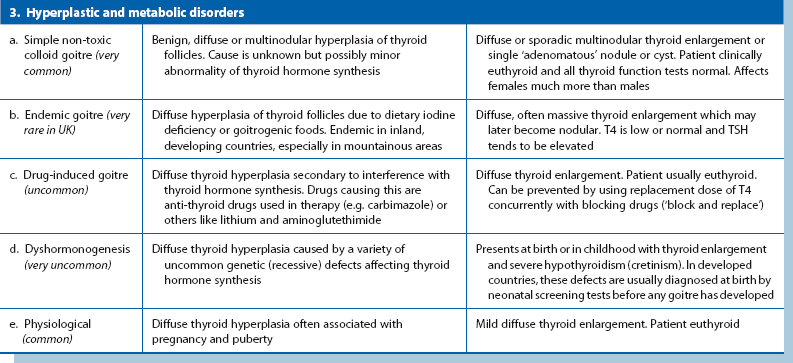

Thyroid malignancies (Table 49.2)

Papillary carcinoma: Papillary carcinoma constitutes about two-thirds of thyroid malignancies in adults and nearly all in children. Females are affected three times more than males and the peak incidence is 30–45 years. Histologically, the tumour forms a complex branching papillary structure with a fibrovascular stroma, often containing characteristic calcified ‘psammoma bodies’. Epithelial dysplasia ranges between apparently benign and obviously malignant but all tumours grow slowly. Papillary carcinomas are microscopically multicentric in about 80% and about one-third affect both lobes; this is important in planning treatment. The tumour occasionally invades locally into trachea or oesophagus.

Symptoms and signs: Clinically, papillary carcinoma presents as a slow-growing solitary thyroid or an enlarged lymph node close to the gland. The patient is euthyroid. Isotope scanning shows no uptake in the nodule. Sometimes, other tumour foci in the gland are large enough to manifest as ‘cold nodules’ too. The diagnosis is usually made nowadays by FNAC. A patient presenting with just an enlarged cervical lymph node may be diagnosed unexpectedly after excision and histological examination.

Management: The standard management is total thyroidectomy because of the high risk of other foci in the gland. Palpable cervical nodes are removed at the same operation. Total thyroidectomy is also recommended because recurrent local disease, lymph node or distant metastases can then be treated effectively with radioiodine (131I); this requires a very high TSH level which only occurs if no normal thyroid tissue remains. A further advantage is that plasma thyroglobulin can be used as a tumour marker to detect recurrent disease.

Follicular carcinoma: Follicular carcinoma is another well-differentiated malignancy. Histologically, neoplastic cells form a well-developed follicular pattern, impossible to distinguish from benign adenomatous hyperplasia on FNAC and even on histology of the surgical specimen. Malignancy may be difficult to diagnose unless there is evident capsular or vascular invasion. Unlike papillary carcinoma, multicentricity is far less common. The peak incidence is 40–50 years, older than papillary carcinoma, but it is three times commoner in women. Generally, follicular carcinoma grows slowly and metastasises late. In contrast to papillary carcinoma, metastasis occurs via the bloodstream to lungs, bone and other remote sites rather than local nodes.

Anaplastic carcinoma: Anaplastic carcinomas are extremely aggressive with an appalling prognosis and are found almost exclusively in the elderly. Most other cancers are less aggressive in older age groups. Most patients die within a year of diagnosis.

Medullary carcinoma: This uncommon malignancy arises from parafollicular or C-cells. The tumour often secretes abnormal quantities of calcitonin, a marker of tumour recurrence after excision. Tumours may also secrete other peptides and amines such as serotonin and ACTH-like peptide. Medullary carcinoma usually arises sporadically but may be transmitted genetically in multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type II (MEN II). This is an autosomal dominant trait with 50% penetrance and is associated with other APUD cell tumours, particularly phaeochromocytoma and parathyroid adenomas. Thus patients with medullary carcinoma should be examined for these before surgery as a phaeochromocytoma would take operative precedence.

Thyroid lymphoma: Thyroid lymphomas are rare and usually arise in pre-existing autoimmune (Hashimoto’s) thyroiditis. Most are non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Diagnosis can only be made histologically, by core needle biopsy or open biopsy, as FNA is inadequate. Treatment is with radiotherapy, and survival depends on whether spread has extended beyond the thyroid capsule. For lesions within the capsule, 5-year survival is 85%, falling to 40% when local spread has occurred.

Goitres and thyroid nodules

Several hyperplastic and metabolic disorders cause diffuse or nodular thyroid enlargement (see Table 49.1).

Idiopathic non-toxic hyperplasia: In developed countries, most goitres referred to surgeons are simple, idiopathic hyperplasia of thyroid follicles. The condition probably begins with diffuse micronodular enlargement; later nodules become heterogeneously enlarged to form a multinodular colloid goitre. Within the same spectrum are solitary hyperplastic nodules (often adenomas) and thyroid cysts, which are huge colloid-filled follicles or else contain straw-coloured fluid.

The reasons patients reach surgeons with thyroid enlargement are:

• A goitre has become so large as to be cosmetically unacceptable

• A localised lump has appeared in the thyroid region. This may be a solitary adenomatous nodule, a cyst or, in 10%, thyroid cancer. The apparent solitary lump may be part of an asymmetrical multinodular or multicystic enlargement

• A pre-existing multinodular goitre has undergone rapid asymmetric change

• The patient has become hyperthyroid

• The patient has developed stridor from tracheal compression caused by enlargement of a retrosternal extension

Surgical management of goitre: The indications for surgery in idiopathic goitre are:

In principle, only enough thyroid tissue is removed to achieve the objective, but in multinodular goitre, recurrence is likely and best treatment is total thyroidectomy with lifetime thyroxine replacement.

Embryology: The thyroid originates as a midline diverticulum between the first two branchial pouches. Its origin is represented in the adult by the foramen caecum, visible at the junction of the anterior two-thirds and the posterior third of the tongue. The thyroid diverticulum forms the thyroglossal duct which extends caudally through the developing tongue. It passes down in relation to the hyoid bone (in front of, through or behind it) to reach its normal position below the larynx. By this time, it has become a bilobed structure with the lobes connected by a narrow central isthmus. The thyroglossal duct later degenerates. The calcitonin-secreting C-cells originate from the ultimobranchial body of the fifth pouch.

Thyroglossal cyst and ‘fistula’: Part of the thyroglossal duct may persist and become cystic. A thyroglossal cyst presents in children and occasionally adolescents as a smooth, rounded, midline swelling in the neck. Most thyroglossal cysts occur below the hyoid, although rarely they occur in the submental region. A diagnostic feature is that the cyst rises when the patient swallows or protrudes the tongue. Most thyroglossal cysts are asymptomatic but they are prone to inflammation which causes pain and swelling. If an inflamed cyst is surgically drained, it may become an intermittently discharging sinus, often incorrectly described as a thyroglossal fistula (Fig. 49.9).

Ectopic thyroid tissue: An ectopic thyroid is a rare congenital abnormality resulting from interruption of normal descent. It may present like a thyroglossal cyst or as a lump in the tongue. As this may be the patient’s only thyroid tissue, isotope scanning should check if there is thyroid tissue in the normal position before proceeding to excision.

Disorders of parathyroid glands

Symptoms and signs

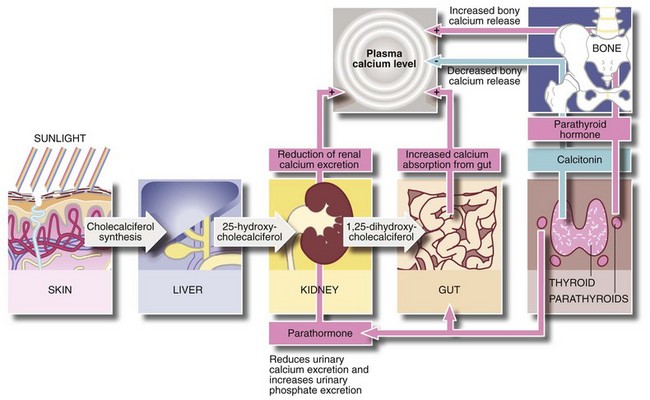

Raised plasma calcium levels cannot be tolerated for long without causing serious systemic problems or damage to bone. From Figure 49.10, it might seem paradoxical that urinary tract calculi are a common presenting feature of hyperparathyroidism, since parathormone reduces urinary calcium excretion. The probable reason for stone formation is the excess phosphate excretion. This is associated with increased urinary alkalinity, which predisposes to precipitation of calcium salts.

Control of plasma calcium (Fig. 49.10)

Parathormone raises plasma calcium levels in the following ways:

• Increases osteoclastic activity and release of calcium from bone matrix, liberating calcium into the circulation

• Enhances renal tubular reabsorption of calcium and diminishes reabsorption of phosphate, thereby increasing the renal clearance of phosphate

• In the presence of vitamin D, it promotes calcium absorption from the small intestine

Vitamin D (as cholecalciferol) is produced by the action of sunlight on cholesterol derivatives in skin. Cholecalciferol is then converted to 25-hydroxycholecalciferol in the liver, and is further hydroxylated by the renal tubules to the active compound 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol. This active compound is required for intestinal absorption of calcium. Calcitonin, produced by C-cells of the thyroid gland, probably plays little part in normal calcium homeostasis.

Types of hyperparathyroidism

Hyperparathyroidism is classified as follows:

a: Single parathyroid adenoma The most common cause of primary hyperparathyroidism, found in 80% of cases. One of the four parathyroid glands becomes replaced by an enlarged benign neoplasm which secretes parathormone in excessive amounts. Secretion by the other parathyroids is suppressed.

Secondary and tertiary hyperparathyroidism: In secondary hyperparathyroidism, there is an abnormal chronic stimulus to parathormone production and the glands undergo diffuse hyperplasia. This occurs most often in chronic renal failure (including nearly all patients on dialysis to some degree) but also occurs in vitamin D deficiency. The altered calcium/phosphate physiology in chronic renal insufficiency includes:

• Damage to the glomerulus causing phosphate retention which leads to hyperphosphataemia

• Hyperphosphataemia inhibits calcium absorption by the gut, reducing absorption of calcium to a minimum

• Renal tubular injury leads to reduced renal production of 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol (1,25-DHCC)

• The low blood calcium causes the negative feedback system to increase elaboration of parathormone. This promotes osteoclastic activity, restoring calcium levels but causing the bone disorders of osteomalacia and osteitis fibrosa cystica

• The raised product of calcium and phosphate in the blood leads to ectopic calcification in abnormal sites

After renal transplantation, hyperparathyroidism may persist if the hypertrophied parathyroid glands fail to return to normal. The glands continue to over-secrete in an autonomous fashion with normal or even elevated serum calcium levels. This is described as tertiary hyperparathyroidism with clinical effects similar to secondary hyperparathyroidism.

Management of hyperparathyroidism

Surgical management: Surgery is the only definitive treatment for primary and tertiary hyperparathyroidism. Secondary hyperparathyroidism is managed by treating renal failure and giving phosphate absorbing agents, although parathyroidectomy may be necessary if there is severe bone resorption. Hypercalcaemia due to ectopic parathormone production is managed medically as it is rarely possible to resect a tumour secreting parathormone-like protein.

Complications of parathyroidectomy are similar to those of thyroid surgery (see Box 49.3 earlier). Hypoparathyroidism is more likely and plasma calcium must be carefully monitored in the early postoperative period and treated if abnormally low.