Disorders of the thumb

Disorders of the inert structures

The three following conditions are quite common.

Rheumatoid arthritis

Both first carpometacarpal joints are frequently affected in rheumatoid arthritis and respond well to intra-articular triamcinolone. Surgery is seldom necessary but, if so, resection arthroplasty is preferred.1

Traumatic arthritis

The patient describes an injury to the thumb, usually overstretching. Discomfort and pain are experienced over the thenar area and the radial side of the wrist. The backward movement during extension elicits pain and is limited. The radiograph is negative.1

Arthrosis

Arthrosis of the trapeziometacarpal joint, or ‘rhizarthrosis’, is very common. It occurs most frequently in middle-aged or postmenopausal women2,3 and affects at least 1 in 3 women over 65 and a quarter of men over 75.4 Rhizarthrosis is often bilateral and is sometimes found in association with arthrosis at the distal interphalangeal joints of the fingers.5 The aetiology is still very unclear. There is evidence that ligament laxity6 and trapeziometacarpal subluxation are important early events in the development of thumb arthrosis.7

Inspection often reveals a dorsoradial prominence of the thumb metacarpal base secondary to subluxation and osteophyte formation. Later on, adduction and Z-deformity of the thumb develop8: the first metacarpal is displaced radially and dorsally and the metacarpophalangeal joint is in a hyperextended position. The thenar muscles are atrophic.

On examination, the combined extension–abduction movement is limited and extremely painful. Crepitus may be felt, especially when the joint is axially compressed and then circumducted – the ‘grind’ test.9,10

The radiographic changes in trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis are classified into four stages, ranging from mild joint narrowing and subchondral sclerosis to complete joint destruction with cystic changes and bone sclerosis.11 The final stage shows clear signs of sclerosis of the bone, gross osteophytes and a metacarpal that is displaced radially and dorsally. However, care must be taken to base the diagnosis not only on radiographic evidence, but also on symptoms and the physical examination. Most people with radiographic evidence of degeneration of the trapeziometacarpal joint remain asymptomatic and, when questioned, only 28% will admit to pain.12

Treatment

The treatment that is chosen depends on the stage of the arthrosis and the functional disability of the joint (Table 24.1). Classically, conservative treatment of osteoarthritis of the trapeziometacarpal joint includes analgesics, joint protection, strengthening exercises of the intrinsic and extrinsic muscles of the thumb, and splints.13 Surgical management is recommended to relieve intractable pain.

Table 24.1

Summary of treatment of capsular disorders

| Deep friction | Intra-articular injection | Surgery |

| – | Rheumatoid arthritis | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Traumatic arthritis | Traumatic arthritis | – |

| Early arthrosis | Moderate arthrosis | Severe arthrosis |

Later in the course of the condition, intra-articular triamcinolone can be tried. It usually has a temporary result only. An open label trial found that steroids had no benefit on carpometacarpal pain at 26 weeks,14 while a randomized controlled trial evaluating steroids against placebo injection showed that steroids had no benefit in moderate to severe trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis at 24 weeks.15 However, the long-term results of triamcinolone are more effective when a traumatic arthritis has supervened.

During the last few decades, intra-articular injections with hyaluronic acid have been promoted as a valuable alternative to intra-articular injections with steroids.16 A few open label trials17,18 found that hyaluronic acid reduced pain and improved grip strength during 6-month follow-up, and two randomized controlled trials stated ‘non-inferiority’ of hyaluronic acid compared with steroids for pain relief at 26 weeks.19,20

Indications for surgical intervention in trapeziometacarpal arthritis are similar to those for arthroplasty of most joints: persistent pain, decreased function, instability, and failure of conservative management.21,22 Surgical options vary with the stage and nature of the disease. In the early stages, trapeziometacarpal ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition procedures23–27 have been shown to provide good symptomatic relief. For severe or late-stage disease, some have advocated arthrodesis of the trapeziometacarpal joint, assuming that there is good mobility of the joints proximal and distal.28–30 Arthroplasty techniques have ranged from simple partial or complete trapeziectomy to various implant and ligament interposition and reconstructions.31,32 These techniques have been generally indicated for stage II or greater disease once conservative management has failed.

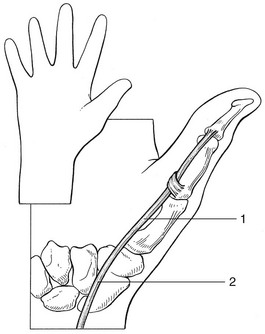

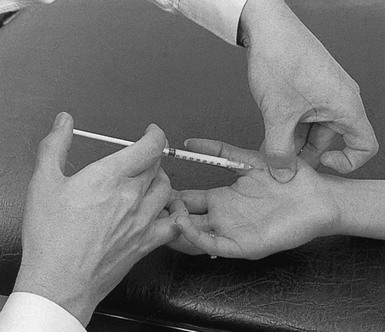

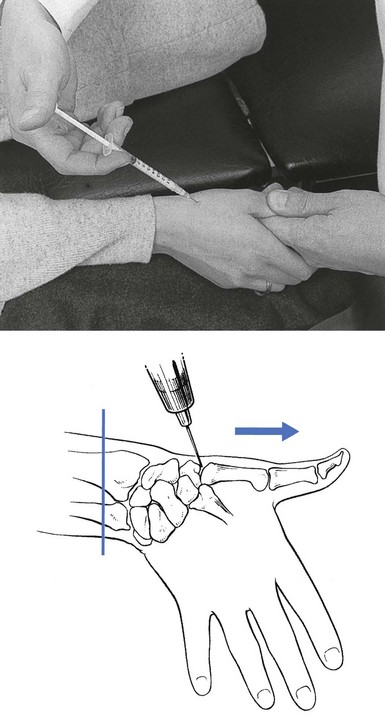

Technique: intra-articular injection

The patient lies supine on a high couch. The physician takes the patient’s outstretched hand on to his or her knee, with the thumb uppermost. With one hand the joint is palpated in the anatomical snuffbox. Caution is necessary not to mistake the edge between the metacarpal bone and an osteophyte for the joint line. With the other hand, slight traction (arrow in Fig. 24.1) and ulnar deviation are needed to open the joint. If the patient relaxes properly, the joint line can be identified by a small gap, which is marked with the nail of the palpating thumb.

Fig 24.1 Intra-articular injection.

A 1 mL syringe, filled with 10 mg triamcinolone acetonide, is fitted with a thin needle, 2 cm long. Traction is applied again. The needle enters at the marked line just proximal to the first metacarpal on the extensor surface. Care must be taken to avoid the radial artery and the extensor pollicis tendons. To avoid the radial artery, the needle should enter towards the dorsal (ulnar) side of the extensor pollicis brevis tendon. The needle is then directed at an angle of 60° to the horizontal. At about 1 cm, the tip is felt entering the joint capsule. If it strikes bone at less than 1 cm, the position is not intra-articular and should be adjusted until the tip is felt entering the joint. The injection is then given.33

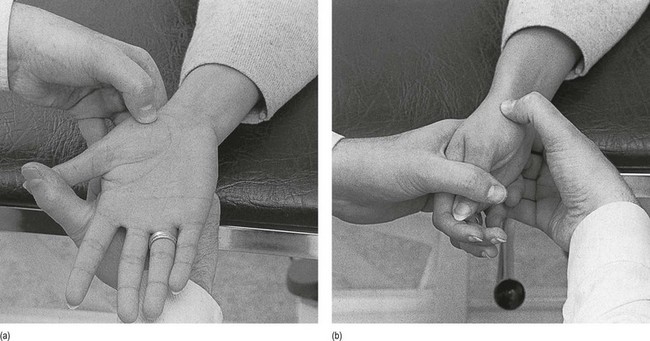

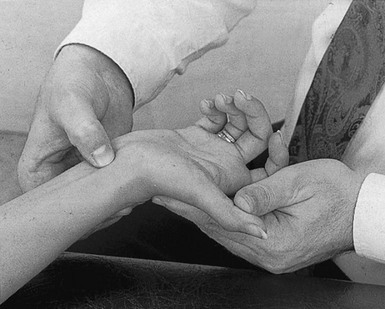

Technique: deep transverse friction to the anterior capsule

With the thumb of the other hand, friction is performed parallel to the joint line. Counterpressure is taken by the fingertips on the proximal interphalangeal joints of the supporting hand (Fig. 24.2a).

Technique: deep transverse friction to the anterolateral capsule

Friction is imparted at the joint line and parallel to it with the thumb of the other hand. Counterpressure is given with the fingers on the ulnar aspect of the patient’s hand (Fig. 24.2b). It is important to ensure that the thumb remains palmar to the extensor pollicis brevis tendon, in that the lesion lies at the anterolateral aspect of the joint.

Disorders of the contractile structures

Pain

Resisted extension

Abductor pollicis longus, and extensor pollicis brevis (first tendon sheath)

Intersection syndrome

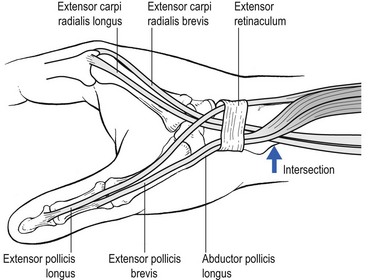

Intersection syndrome is a specific painful disorder of the forearm that is relatively common but sometimes not correctly diagnosed clinically. It has also been referred to in the literature by the terms ‘peritendinitis crepitans’, ‘oarsmen’s wrist’, ‘crossover syndrome’, ‘subcutaneous perimyositis’, ‘squeaker’s wrist’, ‘bugaboo forearm’ or ‘abductor pollicis longus syndrome’.34 Dobyns et al introduced the term ‘intersection syndrome’, an anatomical designation related to the area in which the musculotendinous junctions of the first extensor compartment tendons (abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis tendons) intersect the second extensor compartment tendons (extensor carpi radialis longus and extensor carpi radialis brevis tendons), at an angle of approximately 60° (Fig. 24.3).35

The most plausible pathophysiology is that of a peritendinitis at the intersection of the two tendinous compartments, which spreads upwards to the musculotendinous junction. The lesion may also lie somewhat more proximally in the muscle bellies; hence the name, ‘myosynovitis’.36 This is shown by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings demonstrating the presence of peritendinous oedema concentrically surrounding the second and the first extensor compartments, beginning at the point of crossover, 4–8 cm proximal to the Lister tubercle and extending proximally.37

The lesion always results from occupational overuse or after unusual effort. It is often associated with sports-related activities, such as rowing,38 canoeing, playing raquet sports, horse riding and skiing.39,40

After an initial stage involving a great deal of pain and disability, the condition may evolve towards a more chronic state. Spontaneous cure may take many months and only occurs when the patient gives the wrist complete rest. Treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, immobilization and infiltration of steroid or local anaesthetic does not always lead to swift, full and permanent recovery. Deep transverse friction, however (three times a week, over 2 weeks), is extremely successful in this condition, to such a degree that all other treatments must be considered obsolete. This view was confirmed by Paton in 1978,41 who had used deep transverse friction since 1947 without failure. Bisschop describes 62 cases – 48 men and 14 women – that he treated between 1975 and 1982. The onset was recent (less than 6 weeks) in 55 cases and chronic (2.6 months on average) in 7. Forty-eight of the patients received other treatments, with poor results: steroid infiltration in 16 cases; local anaesthetic infiltration in 4; plaster immobilization in 13 (average 1.8 weeks); partial immobilization with tape in 2; ice friction in 4; physiotherapy in 9. Deep transverse friction – performed three times a week for 15 minutes – led to complete recovery in all but one case, with an average of 6.7 treatments, and 39 patients improved from the first treatment onwards.42

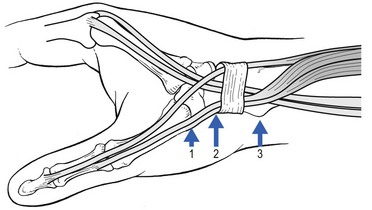

Technique: deep transverse friction

The patient’s forearm rests in pronation on the couch, the hand over its edge. With the contralateral hand the therapist brings the patient’s wrist and thumb into flexion (Fig. 24.4). This stretches the tendons. The other hand takes hold of the patient’s wrist; the thumb then lies flat on the site of the lesion.

Tenovaginitis of the first compartment

Mechanical tenovaginitis

Fritz de Quervain, a Swiss physician, is given credit for first describing this condition in a report of five cases in 1895.43 The disorder has since been known as de Quervain’s disease, tenovaginitis stenosans or styloiditis radii.44 Although the term ‘stenosing tenosynovitis’ is frequently used, the pathophysiology of de Quervain’s disease does not involve inflammation. On histopathological examination, de Quervain’s disease is not characterized by inflammation, but by thickening of the tendon sheath and most notably by the accumulation of mucopolysaccharide, an indicator of myxoid degeneration.45 Therefore de Quervain’s disease should be seen as a result of intrinsic, degenerative mechanisms rather than extrinsic, inflammatory ones. The term ‘styloiditis radii’ is also a misnomer as the lesion is not bony or periosteal.

Incidence of de Quervain’s disease has risen considerably in recent decades.46 It occurs mostly in women, with an average age of 47, and almost never appears before the age of 30.47 A significant association was noted in patients with de Quervain’s disease after pregnancy.48 The cause is presumed to be endocrine in origin and similar to the carpal tunnel syndrome described during pregnancy and the lactating postpartum period.49

Very often de Quervain’s disease comes on spontaneously, but it can also result from overuse. Swift repeated movement with exertion of considerable strength is a possible cause.50

Symptoms consist of pain and/or tenderness at the radial styloid, sometimes radiating down to the thumb and up the lower forearm. Often there is localized swelling over the distal part of the radius. The patient finds the symptoms very disabling, preventing the hand from being used properly. Triggering may complicate the more severe forms51 and demonstrates a more recalcitrant course when treated non-operatively.52

On examination, resisted extension and abduction of the thumb are painful. Passive movements of wrist and thumb also cause pain, as they slide the tendon up and down within its irritated sheath, so setting up painful friction. Very occasionally, resisted radial deviation of the wrist also hurts because the thumb tendons assist this movement. Finkelstein’s test (deviating the wrist to the ulnar side, while the patient makes a fist with the thumb inside the fingers) reproduces the symptoms.53 Some consider this pathognomonic.54,55 Because the lesion is a tenovaginitis, crepitus is always absent but localized swelling can often be palpated.

Palpation must be performed over a wide area, as there are three possible localizations for the lesion56: at the tenoperiosteal insertion of the abductor pollicis longus into the base of the first metacarpal bone; at the level of the carpus; and at the groove on the lower extremity of the radius (Fig. 24.5).

Spontaneous recovery may take 3–4 years. However, treatment is quite simple. The lesion responds remarkably well to one or only occasionally two injections with triamcinolone suspension,57 provided that the injection is correctly placed between tendon and tendon sheath. The effectiveness of injection therapy is often attributed to the anti-inflammatory effects of corticosteroids but the exact mechanism of action remains unclear. Reviews of the effectiveness of corticosteroid injection for de Quervain’s disease showed success rates between 78 and 89%.58–61 In a controlled, prospective, double-blind study by Zingas et al, the accuracy of infiltration in the first extensor compartment was defined and correlated with clinical relief of the disorder. The authors concluded that only those patients in whom the steroid solution really entered the tendon sheath were cured.62 Failure to inject may therefore be caused by misplacement of the needle or by anatomical variations of the tendon sheaths. Anatomical63 and ultrasonographic64 studies confirm the observations during surgery65 that the first extensor compartment may contain a septum separating the extensor pollicis brevis tendon from the abductor pollicis longus. During a study of variants of the tendon of the abductor pollicis longus in 110 upper extremities, Melling et al found an intertendinous septum in 30%.66 This was recently confirmed by Gousheh.67 Leslie et al found that most wrists for which injection fails have a separate extensor pollicis brevis compartment at surgical release. They recommend a second, more dorsal injection in patients when the first has failed.68

Other treatments, such as deep transverse friction, ointments and immobilization, should be regarded as obsolete. Decompressive surgery is only used in those rare cases that do not respond to conservative treatment.69 Simple decompression of both tendons and partial resection of the extensor ligament give excellent long-term results.70 For those patients who have a septum in the first extensor compartment, Yuasa and Kiyoshige suggest decompressing only the extensor pollicis brevis subcompartment.71

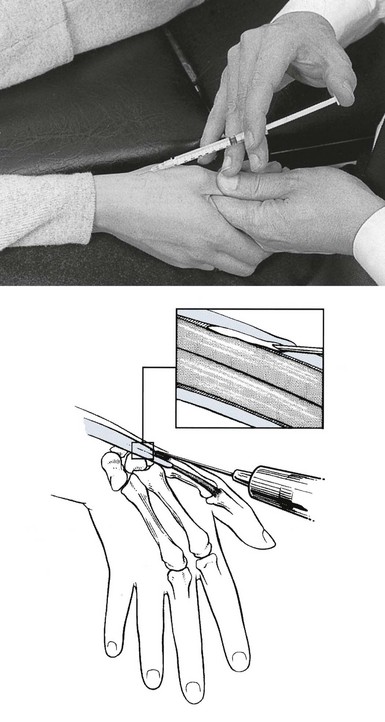

Technique: injection

A 1 mL syringe is filled with 10 mg triamcinolone acetonide and fitted with the thinnest possible needle. A point is chosen just proximal to the base of the first metacarpal bone and the needle is thrust in almost horizontally between the two tendons so that the tip comes to lie in the common tendon sheath. When the fluid is forced in, the palpating fingers feel a small, sausage-shaped swelling along the course of the tendons (Fig. 24.6); 0.5–1 mL of fluid can be injected before counterpressure is experienced on the barrel of the syringe.

Extensor pollicis longus

Pain on resisted extension of the thumb is rare and is the consequence of a lesion of the tendon of the extensor pollicis at its carpal extent. Overuse (‘drummer boy palsy’), forced wrist extension, direct trauma or distal fractures of the radius may all precipitate an extensor pollicis longus tendinitis.72 Pain is felt over the dorsal aspect of the wrist and can be reproduced by testing resisted extension of the thumb.

Treatment consists of deep transverse friction and the condition takes about 2 weeks to cure.

Resisted flexion

Flexor pollicis longus

Tenosynovitis of the flexor pollicis longus may present at two different sites which can be differentiated by palpation: at the level of the first metacarpal (Fig. 24.7), where it responds well to an infiltration of triamcinolone but not to deep transverse friction; and at the level of the carpus, where crepitus may be present. Deep transverse friction is then effective.

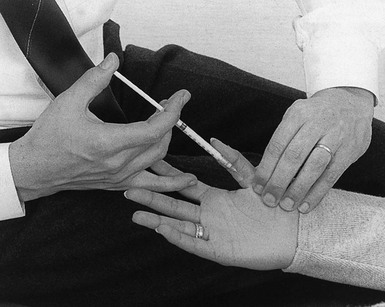

Technique: infiltration

The patient sits with the hand resting on the couch. When the patient is asked to flex the thumb against resistance, the tendon can be palpated and the lesion thus precisely located. The tender spot along the first metacarpal shaft is identified. A syringe filled with 10 mg of triamcinolone suspension fitted with the thinnest possible 2 cm needle is used. The needle is inserted at the level of the tenderness and drug is infiltrated using several withdrawals and reinsertions along the inflamed tendon (Fig. 24.8).

Technique: friction

The patient sits with the hand on the couch. The therapist sits in front of the patient’s hand. With the contralateral hand, the wrist and thumb are brought into extension. With the thumb of the other hand, the tender spot is identified, which is deep in between the tendons of flexor carpi radialis and palmaris longus, level with the carpus. The tendon can be felt when the patient is asked to perform flexion and extension of the thumb. Counterpressure is applied with the fingers at the dorsum of the patient’s wrist (Fig. 24.9). Friction is started at the radial side of the tendon and ended at the ulnar side. The movement is performed by a pronation–supination movement of the forearm.

Trigger thumb

A tendinous node frequently forms on the flexor pollicis longus and becomes engaged in the tendon sheath. The mechanism is as follows: the nodule catches the proximal end of the fibrous sheath at the carpometacarpal pulley with flexion of the thumb, causing the symptoms of trigger thumb with extension. Initially, patients experience intermittent pain, swelling and triggering of the involved digit. In the most severe state, the digit becomes locked in the flexed position, after which the patient has to extend the joint passively with the help of the other hand. A snap and pain may accompany this.73 This typical history suggests the diagnosis, because resisted movements of the thumb do not elicit pain. The tender node can be palpated, just proximal to the head of the first metacarpal bone, and is felt to move when the thumb is flexed and extended.

Spontaneous cure may occur but takes several months.74 One infiltration with triamcinolone is usually curative.75 When the condition recurs, simple surgery to split the tendon sheath longitudinally will give lasting relief from symptoms.76

Technique: infiltration

The patient lies supine on the couch and the operator sits adjacent. The patient’s hand is placed on the operator’s thigh, palm upwards. A tuberculin syringe is filled with 1 mL of a 10 mg/mL triamcinolone solution and attached to a thin needle, 2 cm long. With one finger the tender node, which lies just proximal to the metacarpophalangeal joint, is identified. The needle is inserted about 1 cm distally and directed toward the palpating finger (Fig. 24.10). Half of the solution is infiltrated around, the rest into the nodule.

Weakness

Rupture

A tendinous rupture is easily detected by clinical examination.

Rupture of the extensor pollicis longus tendon occurs rarely after a fracture at the distal extremity of the radius (Colles’ fracture); it usually happens some weeks later as the result of the tendon being frayed by a bony callus.77,78 It is also seen in patients with advanced rheumatoid arthritis.

Surgical repair is the appropriate treatment and, in acute cases, this should be done with some urgency to prevent a second rupture, which often follows.79,80

Nerve lesions

Nerve lesions causing weakness of the thumb may lie at different levels (Table 24.2).

Table 24.2

Nerve lesions and weakness of the thumb

| Weakness | Muscle | Nerve |

| Extension | Extensor pollicis longus | Radial |

| Extensor pollicis brevis | Radial | |

| Flexion | Flexor pollicis longus | Anterior interosseous |

| Flexor pollicis brevis | Ulnar/(median) | |

| Abduction | Abductor pollicis longus | Posterior interosseous |

| Abductor pollicis brevis | Median | |

| Adduction | Adductor pollicis | Ulnar |

| Opposition | Opponens pollicis | Median |

• C8 nerve root: compression of the C8 nerve root, usually caused by a C7 disc protrusion, leads to weakness of adduction and extension of the thumb. This is accompanied by weakened ulnar deviation of the wrist.

• Brachial plexus: when the lower trunk of the brachial plexus becomes affected at the thoracic outlet – for example, as the result of compression by a cervical rib – there may be marked wasting of the abductor pollicis brevis, which does not necessarily cause weakness of abduction of the thumb. In advanced cases, weakness of the muscles innervated by the median and ulnar nerves may be detected.

• Median nerve: long-standing compression of the median nerve in the carpal tunnel may lead to slight weakness and wasting of the thenar muscles.

• Posterior interosseous nerve: a lesion of the posterior interosseous nerve at the elbow results in weakness of thumb abduction and finger extension (see online chapter Nerve lesions and entrapment neuropathies of the upper limb).

• Ulnar nerve: entrapment of the ulnar nerve in the hand gives rise to weakness of thumb adduction.

References

1. Gunther, SF. Carpometarcarpal joint of the thumb. In: Lichtman DM, Alexander AH, eds. The Wrist and its Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1997:443–458.

2. Burton, RI, Pellegrini, VD, Jr., Surgical management of basal joint arthritis of the thumb, Part II: ligament reconstruction with tendon interposition arthroplasty. J Hand Surg 1986; 11A:324–332. ![]()

3. Pellegrini, VD, Jr., Osteoarthritis at the base of the thumb. Orthop Clin North Am. 1992;23(1):83–102. ![]()

4. Haara, MM, Heliövaara, M, Kröger, H, et al, Osteoarthritis in the carpometacarpal joint of the thumb. Prevalence and associations with disability and mortality. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(7):1452–1457. ![]()

5. Dahaghin, S, Bierma-Zeinstra, S, Ginai, A, et al, Prevalence and pattern of radiographic hand osteoarthritis and association with pain and disability (the Rotterdam study). Ann Rheum Dis 2005; 64:682–687. ![]()

6. Jónsson, H, Elíasson, GJ, Jónsson, A, et al, High hand joint mobility is associated with radiological CMC1 osteoarthritis: the AGES-Reykjavik study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17(5):592–595. ![]()

7. Hunter, DJ, Zhang, Y, Sokolove, J, et al, Trapeziometacarpal subluxation predisposes to incident trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis (OA): the Framingham Study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2005; 13:953–957. ![]()

8. Menon, J, The problem of trapeziometacarpal degenerative arthritis. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1983; 175:155. ![]()

9. Swanson, AB, Disabling arthritis at the base of the thumb: treatment by resection of the trapezium and flexible (silicone) implant arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg 1982; 54A:456. ![]()

10. Merritt, MM, Roddey, TS, Costello, C, Olson, S, Diagnostic value of clinical grind test for carpometacarpal osteoarthritis of the thumb. J Hand Ther. 2010;23(3):261–267. ![]()

11. Eaton, RG, Glickel, SZ, Trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis. Staging as a rationale for treatment. Hand Clin. 1987;3(4):455–471. ![]()

12. Armstrong, AL, Hunter, JB, Davis, TR, The prevalence of degenerative arthritis of the base of the thumb in post-menopausal women. J Hand Surg Br. 1994;19(3):340–341. ![]()

13. Gomes Carreira, AC, Jones, A, Natour, J, Assessment of the effectiveness of a functional splint for osteoarthritis of the trapeziometacarpal joint on the dominant hand: a randomized controlled study. J Rehabil Med. 2010;42(5):469–474. ![]()

14. Joshi, R, Intraarticular corticosteroid injection for first carpometacarpal osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol 2005; 32:1305–1306. ![]()

15. Meenagh, GK, Patton, J, Kynes, C, Wright, GD, A randomised controlled trial of intra-articular corticosteroid injection of the carpometacarpal joint of the thumb in osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(10):1260–1263. ![]()

16. Fuchs, S, Monikes, R, Wohlmeiner, A, et al, Intra-articular hyaluronic acid compared with corticoid injections for the treatment of rhizarthrosis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2006; 14:82–88. ![]()

17. Mandl, LA, Hotchkiss, RN, Adler, RS, et al, Injectable hyaluronan for the treatment of carpometacarpal osteoarthritis: open label pilot trial. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(9):2103–2108. ![]()

18. Figen Ayhan, F, Ustün, N, The evaluation of efficacy and tolerability of Hylan G-F 20 in bilateral thumb base osteoarthritis: 6 months follow-up. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28(5):535–541. ![]()

19. Stahl, S, Karsh-Safriri, I, Ratzon, N, et al, Comparison of intra-articular injection of depot corticosteroids and hyaluronic acid for treatment of degenerative trapeziometacarpal joints. J Clin Rheumatol 2005; 11:299–302. ![]()

20. Heyworth, BE, Lee, JH, Kim, PD, et al, Hylan versus corticosteroid versus placebo for treatment of basal joint arthritis: a prospective, randomized, double-blinded clinical trial. J Hand Surg [Am] 2008; 33:40–48. ![]()

21. Kuschner, SH, Lane, CS, Surgical treatment for osteoarthritis at the base of the thumb. Am J Orthop. 1996;25(2):91–100. ![]()

22. Poole, JU, Pellegrini, VD, Jr., Arthritis of the thumb basal joint complex. J Hand Ther. 2000;13(2):91–107. ![]()

23. Eaton, RG, Lane, LB, Littler, JW, Keyser, JJ, Ligament reconstruction for the painful thumb carpometarcarpal joint: a long-term assessment. J Hand Surg 1984; 9A:692. ![]()

24. Robinson, D, Aghasi, M, Halperin, H, Abductor pollicis longus tendon arthroplasty of trapezio-metacarpal joint: surgical technique and results. J Hand Surg 1991; 16A:504–509. ![]()

25. Sigfusson, R, Lundborg, G, Abductor pollicis longus tendon arthroplasty for treatment of arthrosis in the first carpometacarpal joint. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 1991; 25:73–77. ![]()

26. Burton R. American Society for Surgery of the Hand Correspondence Newsletter, 1995 January.

27. Freedman, DM, Clickel, SZ, Eaton, RG, Long-term follow-up of volar ligament reconstruction of the thumb. J Hand Surg Am 2000; 25A:297–304. ![]()

28. Carroll, RE, Hill, NA. Arthrodesis of the carpometacarpal joint of the thumb. J Bone Joint Surg. 1983; 55B:292–294.

29. Stark, HH, Moore, JF, Ashworth, CR, Boyes, JH, Fusion of the first metacarpotrapezial joint for degenerative arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg 1977; 59A:22–26. ![]()

30. Ishida, O, Ikuta, Y, Trapeziometacarpal joint arthrodesis for the treatment of arthrosis. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2000;34(3):245–248. ![]()

31. Bozentka, DJ, Implant arthroplasty of the carpometacarpal joint of the thumb. Hand Clin. 2010;26(3):327–337. ![]()

32. Badia, A, Sambandam, SN, Total joint arthroplasty in the treatment of advanced stages of thumb carpometacarpal joint osteoarthritis. Hand Surg Am. 2006;31(10):1605–1614. ![]()

33. Mandl, LA, Hotchkiss, RN, Adler, RS, et al, Can the carpometacarpal joint be injected accurately in the office setting? Implications for therapy. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(6):1137–1139. ![]()

34. Grundberg, AB, Reagan, DS, Pathologic anatomy of the forearm: intersection syndrome. J Hand Surg 1985; 10:299–302. ![]()

35. Dobyns, JH, Sim, FH, Linscheid, RL, Sports stress syndrome of hand and wrist. Am J Sports Med 1978; 6:236–254. ![]()

36. Howard, NJ. Peritendinitis crepitans. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1937; 19:447–459.

37. Lee, RP, Hatem, SF, Recht, MP, Extended MRI findings of intersection syndrome. Skeletal Radiol. 2009;38(2):157–163. ![]()

38. Wood, MD, Dobyns, JH, Sports related extraarticular wrist syndrome. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1986; 202:93–102. ![]()

39. Palmer, DH, Lane-Larsen, CL, Helicopter skiing wrist injuries: a case report of ‘bugaboo forearm.’. Am J Sports Med 1994; 22:148–149. ![]()

40. Servi, JT, Wrist pain from overuse: detecting and relieving intersection syndrome. Phys Sports Med 1997; 12:41–44. ![]()

41. Paton, HO, Traumatic tenosynovitis of the wrist. BMJ 1978; i:789. ![]()

42. Missotten, J, Stainier, P, Bisschop, P. Ténosynovite des extenseurs et abducteur du pouce. Kinésithérapie Scientifique. 1992; 311:35.

43. de Quervain, F. Über eine Form von chronischer Tendovaginitis. Korresp Bl Schweiz Ärzte. 1895; 25:389.

44. de Quervain, F, On a form of chronic tendovaginitis by Dr. Fritz de Quervain in la Chaux-de-Fonds. 1895. Am J Orthop. 1997;26(9):641–644. ![]()

45. Clarke, MT, Lyall, HA, Grant, JW, Matthewson, MH, The histopathology of de Quervain’s disease. J Hand Surg. 1998;23B(6):732–734. ![]()

46. Walker-Bone, K, Palmer, KT, Reading, I, Coggon, D, Cooper, C, Prevalence and impact of musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb in the general population. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 51:642–651. ![]()

47. Le Viet, D, Lantieri, L, Ténosynovite de de Quervain. Cicatrice horizontale et fixation du lambeau capsulaire. Rev Chir Orthop Repar Appar Mot. 1992;75(2):101–106. ![]()

48. Anderson, SE, Steinbach, LS, De Monaco, D, et al, ‘Baby wrist’: MRI of an overuse syndrome in mothers. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182(3):719–724. ![]()

49. Capasso, G, Testa, V, Maffulli, N, et al, Surgical release of de Quervain’s stenosing tenosynovitis postpartum: can it wait? Int Orthop 2002; 26:23–25. ![]()

50. Armstrong, ThJ, Fine, LJ, Goldstein, SA, et al, Ergonomic considerations in hand and wrist tendinitis. J Hand Surg 1987; 12A:830. ![]()

51. Witczak, JW, Mesear, VR, Meyer, RD, Triggering of the thumb with de Quervain’s stenosing tendovaginitis. J Hand Surg. 1990;15A(2):265. ![]()

52. Albertson, GM, High, WA, Shin, AY, Bishop, AT, Extensor triggering in de Quervain’s stenosing tenosynovitis. J Hand Surg. 1999;24A(6):1311–1314. ![]()

53. Finkelstein, H. Stenosing tenovaginitis at the radial styloid process. J Bone Joint Surg. 1930; 12A:509.

54. Palmer, K, Walker-Bone, K, Linaker, C, et al, The Southampton examination schedule for the diagnosis of musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb. Ann Rheum Dis 2000; 59:5–11. ![]()

55. Pick, RY, De Quervain’s disease: a clinical triad. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1979; 143:165. ![]()

56. Cyriax, JH. Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, vol I, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions, 8th ed. London: Baillière Tindall; 1982.

57. Weiss, AP, Akelman, E, Tabatabai, M, Treatment of de Quervain’s disease. J Hand Surg. 1994;19A(4):595–598. ![]()

58. Jirarattanaphochai, K, Saengnipanthkul, S, Vipulakorn, K, et al, Treatment of de Quervain disease with triamcinolone injection with or without nimesulide. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004; 86-A:2700–2706. ![]()

59. Peters-Veluthamaningal, C, Winters, JC, Groenier, KH, Meyboom-DeJong, B, Randomised controlled trial of local corticosteroid injections for de Quervain’s tenosynovitis in general practice. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2009; 10:131. ![]()

60. Sawaizumi, T, Nanno, M, Ito, H, De Quervain’s disease: efficacy of intra-sheath triamcinolone injection. Int Orthop 2007; 31:265–268. ![]()

61. Richie, CA, Briner, WW, Jr., Corticosteroid injection for treatment of de Quervain’s tenosynovitis: a pooled quantitative literature evaluation. J Am Board Fam Pract 2003; 16:102–106. ![]()

62. Zingas, C, Failla, JM, Van Holsbeeck, M, Injection accuracy and clinical relief of de Quervain’s tendinitis. J Hand Surg. 1998;23A(1):89–96. ![]()

63. Aktan, ZA, Ozturk, L, Calli, IH, An anatomical study of the first extensor compartment of the wrist. Kaibogaku Zasshi. 1998;73(1):49–54. ![]()

64. Nagaoka, M, Matsuzaki, H, Suzuki, T, Ultrasonographic examination of de Quervain’s disease. J Orthop Sci. 2000;5(2):96–99. ![]()

65. Bahm, J, Szabo, Z, Foucher, G, The anatomy of de Quervain’s disease. A study of operative findings. Int Orthop. 1995;19(4):209–211. ![]()

66. Melling, M, Wilde, J, Schnallinger, M, et al, Supernumerary tendons of the abductor pollicis. Acta Anat. 1996;155(4):291–294. ![]()

67. Gousheh, J, Yavari, M, Arasteh, E, Division of the first dorsal compartment of the hand into two separated canals: rule or exception? Arch Iran Med. 2009;12(1):52–54. ![]()

68. Leslie, BM, Ericson, WB, Morehead, JR, Incidence of a septum within the first dorsal compartment of the wrist. J Hand Surg 1990; 15A:88. ![]()

69. Ta, KT, Eidelman, D, Thomson, JG, Patient satisfaction and outcomes of surgery for de Quervain’s tenosynovitis. J Hand Surg. 1999;24A(5):1071–1077. ![]()

70. Scheller, A, Schuh, R, Hönle, W, Schuh, A, Long-term results of surgical release of de Quervain’s stenosing tenosynovitis. Int Orthop. 2009;33(5):1301–1303. ![]()

71. Yuasa, K, Kiyoshige, Y, Limited surgical treatment of de Quervain’s disease: decompression of only the extensor pollicis brevis subcompartment. J Hand Surg. 1998;23A(5):840–843. ![]()

72. Thorson, E, Szabo, R, Common tendinitis problems in the hand and forearm. Orthop Clin North Am. 1992;23(1):65–74. ![]()

73. Wilhelmi, BJ, Mowlavi, A, Neumeister, MW, et al, Safe treatment of trigger finger with longitudinal and transverse landmarks: an anatomic study of the border fingers for percutaneous release. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(4):993–999. ![]()

74. Schofield, CB, Citron, ND, The natural history of adult trigger thumb. J Hand Surg. 1993;18B(2):247–248. ![]()

75. Rhoades, CE, Gelberman, RH, Manjarris, JF, Stenosing tenosynovitis of the finger and thumb. Clin Orthop 1984; 190:238. ![]()

76. Turowski, GA, Zdankiewicz, PD, Thomson, JG, The results of surgical treatment of trigger finger. J Hand Surg Am. 1997;22(1):145–149. ![]()

77. Engkvist, O, Lundborg, G, Rupture of the extensor pollicis longus tendon after fracture of the lower end of the radius – a clinical and microangiographic study. Hand 1979; 11:75. ![]()

78. Kozin, SB, Wood, MB, Early soft-tissue complications after fractures of the distal part of the radius. J Bone Joint Surg. 1993;75A(1):144–153. ![]()

79. Schneider, LH, Rosenstein, RG, Restoration of extensor pollicis longus function by tendon transfer. Plast Recon Surg 1983; 71:533–537. ![]()

80. Ferlic, DC. Extensor indicis proprius transfer for extensor pollicis longus rupture. In: Blair W, Steyers C, eds. Techniques in Hand Surgery. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1996:649–653.