Disorders of the thoracic cage and abdomen

Pain in the thorax or abdomen can be the result of a local problem of either the thoracic wall or the abdominal muscles but it is more often referred from a visceral structure or from another musculoskeletal source, most frequently a disc protrusion. Therefore, it is wise to remember the only safe approach in this area is to achieve a diagnosis by both positive confirmation of the lesion and exclusion of other possible disorders.

Referred pain

Pain referred from visceral structures

All visceral structures belonging to the thorax or abdomen may give rise to pain felt in this area (see Ch. 25). In that the discussion of these disorders is principally the province of internal medicine, only major elements in the history that are helpful in differential diagnosis from musculoskeletal disorders are mentioned here. Acute chest pain is summarized in Box 1.

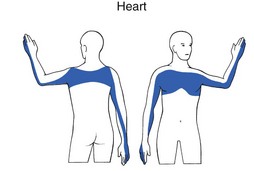

Heart (Fig. 1)

Ischaemic heart disease

The innervation of the heart is derived from the C8–T4 segments. Pain is therefore not only felt in the chest but can also be referred to the ulnar side of both upper limbs, though more commonly to the left.

It is traditionally accepted that pain felt in the chest radiating into the left arm is indicative of myocardial ischaemia, especially when the patient reports it as pressure, constriction, squeezing or tightness. However, none of these descriptions, which are usually regarded as characteristic of ischaemia, is of definitive aid in the differential diagnosis from other non-cardiogenic problems in the thorax. Even relief of pain after the intake of glyceryl trinitrate does not offer absolute confirmation of coronary ischaemia. For clinical diagnosis, a combination of several elements must be present, of which the most important is pain spreading to both arms and shoulders initiated by walking, especially after heavy meals or on cold days.1

Mitral valve prolapse

This condition usually gives rise to mild pain located in the left submammary region of the chest and sometimes also substernally. Occasionally it mimics typical angina pectoris and is sometimes accompanied by palpitations.

Pericarditis

Pain that arises from the pericardium is the consequence of irritation of the parietal surface, mainly from infectious pericarditis, seldom from a myocardial infarction or in association with uraemia. When pericarditis is the outcome of one of the latter two causes it is usually only slight. Pain is normally located at the tip of the left shoulder, in the anterior chest or in the epigastrium and the corresponding region of the back. Three different types of pain can be present. First and most obvious, but rarely encountered, is pain synchronous with the heartbeat. Second is a steady, crushing substernal ache, indistinguishable from ischaemic heart disease. Third and most common is pain caused by an associated localized pleurisy, which is sharp, usually radiates to the interscapular area, is aggravated by coughing, breathing, swallowing and recumbency, and is alleviated by leaning forward.2

Aorta

Aneurysm of the thoracic aorta

This is most frequently the result of arteriosclerosis but is rare by comparison with the same condition below the diaphragm. The majority of small aneurysms remain asymptomatic, but if they expand a boring pain results, usually from displacement of other visceral structures or erosion of adjacent bone. Compression of the recurrent nerve may result in hoarseness and compression of the oesophagus in dysphagia. When acute pain and dyspnoea supervene, this usually indicates that the aneurysm has ruptured, with a likely fatal outcome.

Dissecting aneurysm of the thoracic aorta

This is an exceptional cause of chest pain, occurring mainly in hypertensive patients. The process usually starts suddenly in the ascending aorta, giving rise to severe substernal or upper abdominal pain. Radiation to the back is common and back pain may sometimes be the only feature, expanding along the area of dissection as it progresses distally. The patient often describes the pain as tearing. In most cases, it is not changed by posture or breathing.

When aortic dissection involves the vessels that supply the spinal cord, neurological changes and even paraplegia may result.3

Pleuritic pain

Pleuritic chest pain is a common symptom and has many causes, which range from life-threatening to benign, self-limited conditions. Because neither the lungs nor the visceral pleura have sensory innervation, pain is only present if the parietal pleura is involved, which may occur in inflammation or in pleural tumour. Invasion of the chest wall by a pulmonary neoplasm also provokes pain.

Clinical presentation

Pleuritic pain is localized to the area that is inflamed or along predictable referred pain pathways. Parietal pleurae of the outer rib cage and lateral aspect of each hemidiaphragm are innervated by intercostal nerves. Pain is therefore referred to their respective dermatomes. The central part of each hemidiaphragm belongs to the C4 segment and therefore the pain is referred to the ipsilateral neck or shoulder.

The classic feature is that forceful breathing movement, such as taking a deep breath, coughing, or sneezing, exacerbates the pain. Patients often relate that the pain is sharp and is made worse with movement. Typically, they will assume a posture that limits motion of the thorax. Movements of the trunk which stretch the parietal pleura may increase the pain.

During auscultation the typical ‘friction rub’ is heard. The normally smooth surfaces of the parietal and visceral pleurae become rough with inflammation. As these surfaces rub against one another, a rough scratching sound, or friction rub, may be heard with inspiration and expiration. This friction rub is a classic feature of pleurisy.

Aetiologies

Pneumonia

Although the clinical presentation of pneumonia may vary, classically the patient is severely ill with high fever, pleuritic pain and a dry cough.4

Carcinoma of the lung

In carcinoma of lung, pain is consequent upon involvement of other structures such as the parietal pleura, the mediastinum or the chest wall. Invasion of the chest wall may cause spasm of the pectoralis major muscle, which subsequently leads to a limitation of both passive and active elevation of the arm.

Pleural tumour

Malignant mesothelioma is a diffuse tumour arising in the pleura, peritoneum, or other serosal surface. The most frequent site of origin is the pleura (>90%), followed by peritoneum (6–10%), and only rarely other locations. Mesothelioma is closely associated with asbestos exposure and has a long latency (range 18–70). There is no efficient treatment and the overall survival from malignant mesothelioma is poor (8.8 months).5,6

Pleuritis

This is characterized by a sharp superficial and well-localized pain in the chest, made worse by deep inspiration, coughing and sneezing. Viral infection is one of the most common causes of pleuritic pain.7 Viruses that have been linked as causative agents include influenza, parainfluenza, coxsackieviruses, respiratory syncytial virus, mumps, cytomegalovirus, adenovirus, and Epstein-Barr virus.8

Pulmonary embolism

Pulmonary embolism is the most common potentially life-threatening cause, found in 5–20% of patients who present to the emergency department with pleuritic pain.9,10

Predisposing factors for pulmonary embolism are: phlebothrombosis in the legs, prior embolism or clot, cancer, immobilization, prolonged sitting (aeroplane), oestrogen use or recent surgery.11

Symptoms and signs are mainly dependent on the extent of the lesion. A small embolus may give rise to effort dyspnoea, abnormal tiredness, syncope and occasionally to cardiac arrhythmias. A medium-sized embolus may lead to pulmonary infarction, so provoking dyspnoea and pleuritic pain. In a massive pulmonary embolus, the patient complains of severe central chest pain and suddenly shows features of shock with pallor and sweating, marked tachynoea and tachycardia. Syncope with a dramatically reduced cardiac output may follow. This is a medical emergency: death may follow rapidly.

Acute pneumothorax

This is characterized by a sudden dyspnoea and unilateral pain in the chest, radiating to the shoulder and arm on the affected side and often described as a tearing sensation. Breathing and activity increase the pain. The typical features of pneumothorax are tachycardia, hyperresonance on percussion and decreased breath sounds on auscultation.

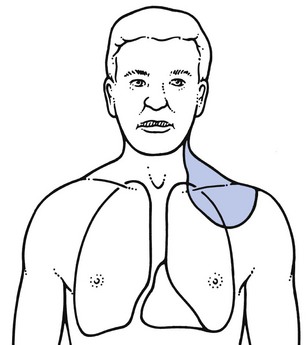

Superior sulcus tumour of the lung (Pancoast’s tumour)

This warrants special attention because 90% of patients suffering from this disorder complain of musculoskeletal pain.12,13 It is frequently mistaken for a shoulder lesion or even for thoracic outlet syndrome, an error which leads to a delay in diagnosis and treatment.14

The superior pulmonary sulcus is the groove in the lung formed by the subclavian artery as it crosses the apex of the lung. Because most apical tumours have some relation to the sulcus, they are often called superior sulcus tumours. They frequently involve the brachial plexus and the sympathetic ganglia at the base of the neck and may destroy ribs and vertebrae.

Pain around the shoulder, radiating down the arm and towards the upper and lateral aspect of the chest is usual and is often worse at night.

Orthopaedic clinical examination produces an unusual pattern of clinical findings. There is often a complicated mixture of cervical, shoulder and thoracic signs. Passive and resisted movements of the cervical spine may be limited and/or painful, the result of involvement of the scaleni and sternocleidomastoid muscles. On examination of the shoulder girdle, a restriction of both active and passive elevation of the scapula may be present. More positive signs are detected during examination of the shoulder.15 Both active and passive elevations of the arm are limited because of spasm of the pectoralis major muscle. Passive shoulder movements may be considerably limited in a non-capsular way. Some resisted movements are weak.

The neurological examination of the upper limb shows weakness and atrophy of the muscles on which consequent is extension of the tumour to the lower trunks of the brachialis plexus (Fig. 2). The only abnormal finding during thoracic examination is pain and limitation on lateral flexion towards the unaffected side explained by putting the affected thoracic wall under stretch.

Fig 2 The clinical symptoms of a superior sulcus tumour of the lung are produced by local extension into the chest wall, the base of the neck and the neurovascular structures at the thoracic inlet.

The clinical picture of Pancoast’s tumour may be completed by some typical findings that are caused by an ingrowth of neurological and vascular structures at the apex of the lung.16

• Horner’s syndrome: this is characterized by an ipsilateral slight ptosis of the upper lid, miosis of the pupil and enophthalmos, together with decreased sweating on the same side of the face. It is the outcome of involvement of the ascending sympathetic pathway at the stellate ganglion on the side of the tumour.17

• Hoarseness: this is the result of involvement of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, which innervates the voice cords. The hoarseness is unusual and unlike that caused by local laryngeal problems.

• Oedema and discoloration of the arm: this occurs if the subclavian vein is obliterated by the tumour.

All the symptoms and signs mentioned (summarized in Box 2), either singly or in combination, call for careful clinical chest examination followed by further investigation by chest radiography or other imaging methods.

Mediastinal problems

Acute mediastinitis

This is a rare inflammation, usually the result of perforation of the oesophagus. The three causes are perforation of malignant tumour, ingestion of caustics leading to necrosis and Mallory–Weiss syndrome, in which vomiting without appropriate relaxation of the oesophagus causes a tear of the oesophagogastric junction, often incomplete in thickness. There is very severe substernal and central dorsal pain of abrupt onset, followed by high fever and shock. Without treatment, it is rapidly fatal.

Mediastinal emphysema

This is usually the consequence of a ruptured pleural bleb or a wound of the chest. Air spreads into the mediastinal tissues, giving rise to sudden or more gradual substernal pain, sometimes radiating into the neck, shoulders and interscapular area. Subcutaneous crepitus above the clavicle is pathognomonic for the condition.

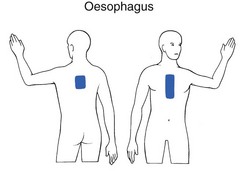

Oesophagus (Fig. 3)

Oesophageal spasm

This occurs suddenly and gives rise to substernal aching not necessarily related to the intake of food. Relief is often obtained by drinking hot water.

Reflux oesophagitis

This is frequently due to a hernia of the stomach through the diaphragmatic hiatus. Pain is felt around the xiphoid process, can be very severe and may radiate to the rest of the sternum, into the back and between the scapulae.18 Pyrosis or heartburn, which begins if the patient lies down immediately after meals, together with a burning sensation on eructation, are the most typical symptoms.

Malignant tumour of the oesophagus

The initial symptoms are food lodgement at the site of the tumour. Later there may be constant anterior or posterior central chest pain, unrelated to eating and mainly the result of extraoesophageal extension of the tumour. Total dysphagia may follow, and remarkable weight loss over a short period of time is an ominous sign.

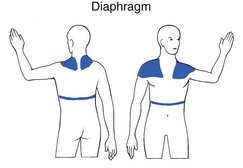

Diaphragm (Fig. 4)

Diaphragmatic irritation

This can be the result of a subphrenic abscess or of air in the abdomen after laparoscopy or laparotomy. Pain arising from the central part of the diaphragm is referred to the base of the neck and into the shoulders, mainly in the third and fourth cervical segments. Pain originating from the peripheral part is felt more at the lower thorax and in the upper abdomen.

Diaphragmatic hernia

This usually occurs due to displacement of the proximal part of the stomach as a whole when the patient is prone or head down or when intra-abdominal pressure is increased, as on straining or lifting. Pain, pyrosis and dysphagia may result. Pain usually disappears in the upright position. Hernia often causes reflux oesphagitis (see above).

Subphrenic abscess

Abscesses that are truly just below the diaphragm can occur either to the right or to the left. Many so-called subphrenic abscesses are in fact below the liver and usually follow a perforation of the gastrointestinal or biliary tract, often after surgery. Signs and symptoms are fever and upper quadrant pain, sometimes with associated shoulder pain and local tenderness along the costal margin. Dyspnoea may be associated. Persistent fever and a history of a recent intra-abdominal sepsis should arouse suspicion.

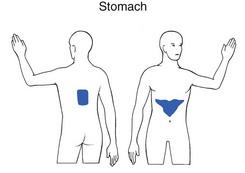

Stomach and duodenum (Fig. 5)

Gastritis

An inflammation of the superficial gastric mucosa may be the result of the intake of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, alcohol or excessive meals. There is usually epigastric pain of short duration.

Gastric or duodenal ulcer

These result in epigastric or substernal pain, often associated with inability to digest food. The pain usually ceases on intake of antacids or food. Other symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, heartburn and flatulence, are atypical. In duodenal ulcer, the pain commonly comes on through the night and also occurs 1– hours after meals. A bout of symptoms over weeks or months may be followed by a similar period of relief. Pain in the back suggests a posterior ulcer that has penetrated a structure such as the pancreas.

hours after meals. A bout of symptoms over weeks or months may be followed by a similar period of relief. Pain in the back suggests a posterior ulcer that has penetrated a structure such as the pancreas.

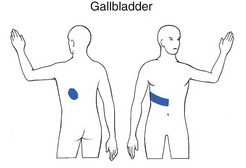

Liver, gallbladder and bile ducts (Fig. 6)

Acute hepatitis

In acute hepatitis, enlargement of the liver, with subsequent stretching of the capsule, can give rise to pain felt in the right hypochondrium and upper abdomen. The development of jaundice is indicative of hepatitis and the liver is tender on palpation. It should be remembered that hepatitis B infections may be preceded in one in four cases by a polyarthritis affecting the smaller joints.

Choledocholithiasis

This provokes spasmodic pain felt mainly in the right hypochondrium. The pain may radiate posteriorly towards the inferior angle of the right scapula (T7–T9).

Cholecystitis

Though traditionally described in females of 20–40 years of age, cholecystitis can occur at any age and in either sex. Localized peritoneal irritation may occur with acute abdominal pain in the right hypochondrium. Pain may radiate into the back and to the right shoulder. Sometimes nausea and vomiting are also present. On palpation, there is local tenderness over the gallbladder.

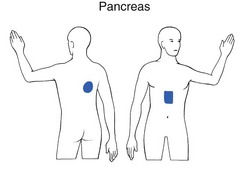

Pancreas (Fig. 7)

Acute pancreatitis

In acute pancreatitis the patient is usually acutely ill with central upper abdominal pain, which may radiate to the back. The clinical features of an ‘acute abdomen’ predominate.

Subacute or chronic pancreatitis

In a high percentage of cases, pain is referred to the back at about the T8 level. The symptoms may be the outcome of obstruction of the pancreatic duct, interstitial inflammation or infiltration by a neoplasm. Patients who suffer from these disorders often get relief in a characteristic position: sitting with the trunk flexed, knees drawn up and the forearms folded around the knees to exert pressure upon it.

Spleen

Pain arising from disorders of the spleen, sometimes due to splenomegaly, is felt in the left hypochondrium and is sometimes referred to the side in the lower half of the thorax (T6–T10).

Appendix

Acute appendicitis is usually the result of an obstruction of the lumen of the appendix by a faecalith. The pain starts in the centre of the abdomen, around the umbilicus and later is sited in the right iliac fossa. Nausea and vomiting are often present. There is local tenderness and guarding on palpation of the right iliac fossa, from localized peritonitis.

Mechanical obstruction of hollow viscera

Abdominal colic is the predominant symptom. Depending on the level of obstruction, it is felt around the umbilicus (small intestine) or at the level of the obstruction (colon).

Distension of the splenic flexure of the colon by gas may give rise to pain in the left hypochondrium, in the precordial area and even in the left shoulder. The pain is often provoked by constipation and heavy meals. Patients usually suffer from gaseousness and aerophagy as well and are relieved by flatus or bowel movement.

Ureteral obstruction provokes pain felt in the patient’s side and in the lateral aspect of the abdomen. It often radiates towards the genitals.

Intra-abdominal vascular disorders

Aneurysm of the abdominal aorta

This is often asymptomatic. On palpation an expansile, pulsating mass may be found. As an aneurysm expands it may give rise to pain in the abdomen or in the back. Acute rupture gives rise to very acute epigastric pain, radiating into the back. Shock supervenes and surgical intervention is urgently needed.

Mesenteric ischaemia

Mesenteric arterial occlusion sometimes comes on very suddenly, provoking catastrophic abdominal pain. In other cases, the pain is much milder and more progressive, setting in over 2 or 3 days. Vomiting and bloody diarrhoea usually occur. Careful history for other localizations of vascular abnormalities is always necessary.

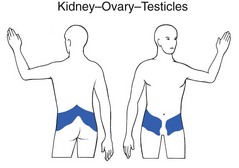

Disorders of the genitals (Fig. 8)

A torsion and rupture of an ovarian cyst gives rise to symptoms almost identical to those in acute appendicitis. In subacute torsion, the patient complains of repeated episodes of sharp abdominal pain. Each attack lasts only for a short period of time.

Children and adolescents are the chief victims of testicular torsion. There is acute pain in the scrotum, sometimes radiating into the abdomen. Vomiting is often associated.

Parietal peritoneum

Peritonitis

Irritation of the parietal peritoneum can be the result of infection (as in acute appendicitis) or to chemical irritation by intestinal contents (as in a perforated ulcer) and inflammatory exudate (in pancreatitis). The pain is steady and aching and is increased by any augmentation of the intra-abdominal pressure. For this reason, the patient prefers to lie still.

Herpes zoster

Although herpes zoster is not a visceral disorder as such, it is mentioned here because it may result in unexplained pain for a few days before the typical rash appears. The pain is persistent and burning and varies in intensity from mild to severe. The older the patient, the more severe the pain. A rash, consisting of typical grouped vesicles with a unilateral segmental distribution, usually follows within 4 days.

Psychogenic problems

Psychogenic problems may give rise to symptoms and signs in the thoracoabdominal area as well as in the rest of the body. Specific features are absent and the vague history without direct answers to questions, together with several clinical inconsistencies, must put the examiner on guard.

Hyperventilation

Patients who suffer from hyperventilation are usually tense and anxious. They frequently complain of attacks of pins and needles in hands and feet, often associated with faintness, dizziness and precordial pain. The diagnosis is made by provoking the symptoms by asking the patient to hyperventilate.

Pain referred from musculoskeletal structures not belonging to the thoracic cage

Although some of these have already been discussed as part of the clinical examination, they are brought together here in a more schematic way to complete the account of referred pain.

Disc protrusions

Cervical disc lesion

Extrasegmental pain

A posterocentral cervical disc protrusion often gives rise to extrasegmental pain referred into the thorax, most frequently felt between the scapulae above T6. When pain is present in this area, a detailed examination of the cervical spine is immediately indicated. In a cervical disc lesion, the pain is seldom referred lower in the posterior thorax or anteriorly into the chest, but when it is, the thoracic examination remains negative except for flexion of the neck.

Thoracic disc lesion

Extrasegmental referred pain

A posterocentral disc protrusion in the thoracic spine is usually accompanied by posterior interscapular pain spreading extrasegmentally. Symptoms and/or signs of a disc protrusion are found on examination of the thoracic spine. Depending on the type, different pain patterns may result: acute thoracic lumbago, sternal lumbago, chronic thoracic pain and cord compression (see Ch. 27).

Band-shaped unilateral pain

This occurs in secondary posterolateral protrusions and is always preceded by posterior extrasegmental pain. A primary posterolateral protrusion provokes, from the onset, anterior pectoral pain in the absence of previous posterior pain. In the lower thorax, pain may be referred to the groin and even to the testicles.

Non-disc spinal lesions

Many other types of musculoskeletal disorders of the thoracic spine may refer pain into the chest or abdomen and are discussed in Chapter 28.

Disorders of the thoracic cage and abdomen

In this book, disorders are discussed in relation to the clinical examination that is most likely to reveal them. For this reason, many structures such as the sternoclavicular joint, costocoracoid fascia and the first rib, which belong anatomically to the thoracic cage, are discussed under the shoulder girdle, the neck and the shoulder joint.

Lesions of the thoracic cage commonly give rise to local pain and are often the result of a direct blow or a forceful activity during sports.

Disorders of the inert structures

Lesions of the sternum

Fracture and metastases

These give rise to well-localized sternal pain together with tenderness on palpation. A history of injury is usually obtained in the first, while a decline in general health may antedate the second. On clinical examination all movements hurt, as does deep inspiration. A radiograph usually confirms the diagnosis.

Manubriosternal arthritis

This can be the result of ankylosing spondylitis or rheumatoid arthritis.19,20 Monoarticular steroid-sensitive arthritis is rare at this site.21

The patient complains of spontaneous pain at the angle of Louis. Local tenderness and swelling is found on palpation. In ankylosing spondylitis and rheumatoid arthritis other joints are also involved.

Laboratory tests

Tests for rheumatoid disorders should be done. In monoarticular steroid-sensitive arthritis, the manubriosternal joint is the only one affected and laboratory tests are negative.

Radiography

Arthritis may show erosion of the joint margin, presence of subchondral cysts, sclerosis of bone adjacent to the joint and widening or narrowing of the joint space. It may lead to total ankylosis, sometimes even to full destruction and subluxation of this joint.22

Disorders of the sternoclavicular joint

Lesions of the sternoclavicular joint are mainly characterized by local pain at the side of the manubrium or at the base of the neck. The pain is provoked by active and passive elevation of the scapula and arm. Other passive movements are only slightly painful. This combination, in the absence of any other features of a thoracic disc lesion, indicates clinical examination of the shoulder girdle (see online chapter Clinical examination of the shoulder girdle).

Perichondritis of the costochondral joints (Tietze’s syndrome)

This may have either a sudden or a gradual onset and gives rise to spontaneous unilateral pain and swelling of one of the costosternal synchondroses, most frequently that of the second rib.23 It is found at all ages, even in children, and is equally prevalent in males and females.24 It is a self-limiting process often associated with a respiratory infection, although this is not always the rule.

Natural history

The initial symptom is pain, which precedes the local swelling. Heat and erythema are absent. Usually the pain remains local, although radiation has been reported.25 The intensity of the pain ranges from mild to severe, and is increased by deep inspiration and by coughing. The local fusiform or spindle-shaped mass is exquisitely tender and over-lies the affected joint.26,27 When the xiphisternal joint is affected, the mass and pain often increase after eating as the result of a postprandial anterior displacement of the xiphoid.28 Local tenderness is the first symptom to disappear, usually between 10 days and 2 months. Spontaneous pain remains longer, up to several months. The swelling tends to reach a maximum size and either remains stationary or regresses slowly but seldom undergoes total regression. Recurrence may occur.

Disorders of the rib

A fractured rib

This is usually the result of a direct blow to the chest. Nevertheless, fractures as a result of coughing or forceful muscular activity of the upper limb or trunk have been reported.33,34 In fracture without an obvious cause, tumour must always be considered.

The patient complains of severe, well-localized pain, made worse by deep inspiration which may be arrested before reaching its peak. Every active, passive and resisted movement of the trunk which has any effect on the fractured rib is very painful. Which particular movements are positive depends on which rib is fractured and at which part. If the fracture lies in the neighbourhood of the origin of the pectoralis major (second to sixth ribs), resisted adduction and medial rotation of the arm are also painful. Slight movement of the fractured ends provokes sharp well-localized pain. Because a fractured rib is frequently accompanied by an adjacent intercostal muscle sprain, careful palpation of the muscle must follow. The pain from the fracture is felt on the rib itself, but that caused by a sprain is found in between the ribs. A radiograph confirms the diagnosis.

Differential diagnosis must be made from a primary posterolateral disc protrusion in which from the onset the pain is located in the anterior thorax. In disc protrusion, local trauma is not mentioned by the patient, pain is not felt on resisted movements and moving the rib ends on either side of the site of pain is negative. Palpation is not fully reliable because exquisite local tenderness may also be found in disc lesions.

Long floating rib

The tip of a long rib may strike the iliac crest on ipsilateral side flexion and provokes a sharp momentary pain. Severe recurrent symptoms of this kind may indicate removal of the tip of the rib.

The rib-tip syndrome

The slipping rib syndrome was first described by Edgar Cyriax in 1919.33 After an injury to the anterior chest, the anterior cartilaginous tips of the eighth, ninth or tenth rib can remain detached from the bone and may subluxate inferoposteriorly.34 Contact with the intercostal nerve can give rise to pain.

The patient complains of a sharp sudden pain felt at the anterior or inferior margin of the rib on local pressure, during vigorous activity or on deep breathing. Pain can spread posteriorly to the high lumbar level and may remain for some days. Often a popping sensation is felt.35

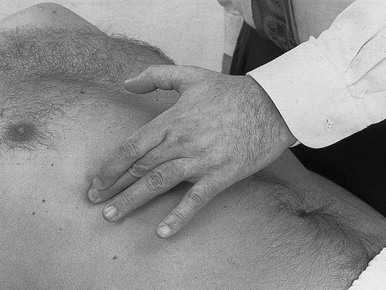

Diagnosis is based on the typical lancinating pain and the local tenderness during the ‘hooking manūuvre’. The hooking manūuvre is a relatively simple clinical test, whereby the clinician places his or her fingers under the lower costal margin and pulls the hand in an anterior direction. Pain or clicking indicates a positive test.36,37 Sometimes active abduction of the arm or ipsilateral side-flexion of the trunk provokes the pain.

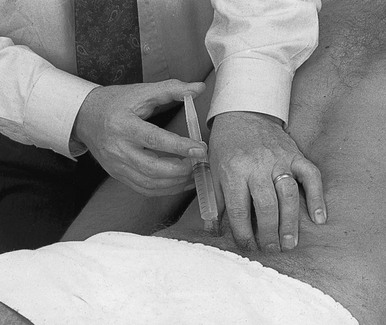

Treatment

This is an infiltration of a mixture of steroid and local anaesthetic around the nerve at the tip of the rib, which brings immediate and sometimes permanent relief.38,39 If the pain recurs, the cartilaginous tip of the rib should be surgically removed.34

The patient lies supine, with the arms elevated. The painful tip is located by palpation. The caudal edge is identified and the lesion marked. A 2.5 cm needle is fitted to a 2 ml syringe filled with 1.5 ml of triamcinolone and 0.5 ml of lidocaine (lignocaine) 2%. The needle is inserted vertically at the site of the lesion, aiming at the lower edge at the anterior aspect of the rib, and pushed in until it touches the bone. The needle is then slightly withdrawn and moved more caudally until it passes just beyond the lower edge. The infiltration is done at this point.

Post-thoracotomy pain

A significant proportion of patients who undergo thoracotomy suffer from chronic pain. It is generally not severe but a small proportion of patients may experience persistent moderately disabling pain. The reported incidence of persistent post-thoracotomy pain lasting for more than 6 months is between 5 and 40%.40–42 As the pain is cutaneous, it is most probably the consequence of damage to an intercostal nerve.

Patients can be treated by a nerve block around the intercostal nerve. This is tried first, with a mixture of local anaesthetic and steroid. Refractory cases require chemical rhizotomy with a 1% solution of phenol. This is usually followed by sensory loss, which is better tolerated than the pain.43

Tumours of the rib

These may be benign, malignant, primary and secondary.44 Multiple myeloma involves the rib directly. Metastases usually derive from primary tumours of lung, kidney, thyroid and breast.

The initial symptom is well-circumscribed pain, spreading and increasing in severity later as the tumour grows or when it invades other neighbouring structures such as the intercostal nerves. Pathological fractures may result.

Disorders of the contractile structures

Muscles of the thoracic cage

Sprained intercostal muscle

This is usually the result of a direct injury to the chest. It may exist alone or in association with a fracture of a rib.

The patient complains of a well-localized pain, which does not radiate. Deep inspiration is painful, as are all trunk movements that stretch the affected intercostal muscle. More than one muscle can be involved, so the whole of the painful area must be carefully palpated.

Differential diagnosis must be made from a fractured rib. In a sprain of the intercostal muscle, palpation is positive between the ribs and not on the rib itself. If the rib is also found to be tender, a fracture is most likely and a radiograph must be obtained.

Treatment

The lesion responds very well to a few sessions of deep transverse friction.

Technique: deep friction (Fig. 9)

The patient adopts a half-lying position and the therapist sits at the contra-lateral side. The tender point(s) in between the ribs are palpated and the middle finger, reinforced by the index finger, is placed there. The fingers are now moved to and fro in line with the ribs, movement obtained by a combination of flexion–extension at the elbow and shoulder. Every lesion should be treated each time, for about 15–20 minutes. Because this type of lesion responds very well to deep transverse friction, cure is obtained in about three to five sessions.

Lesions of the pectoralis major

The localization of the pain draws attention to the thorax, which is why this disorder is included here. However, it is the examination of the shoulder which establishes the diagnosis (see Ch. 12).

In a lesion of the pectoralis major, resisted adduction and internal rotation of the arm are painful. The patient is asked to press both hands against each other with the arms stretched out horizontally in front of the body, which is even more painful.

The lesion usually lies in the muscle belly at the infraclavicular portion or at the latero-inferior part of the muscle, almost in the axilla.

This disorder must be differentiated from a fractured rib, which may give rise to pain on the same shoulder tests. Fracture is associated with pain on deep inspiration and on coughing, as well as with some movements of the trunk. Palpation of the tender spot, with and without contraction of the pectoralis muscle, can be compared. More pain on contraction suggests a problem in the muscle, more pain with the muscles relaxed suggests that the cause is in a rib or the intercostal muscles.

Treatment is deep friction or an infiltration with procaine (see Ch. 15).

Lesions of the latissimus dorsi

This may provoke pain in the posterior thorax, sometimes even at the posterior aspect of the axilla. Pain is elicited on full passive elevation of the arm, resisted adduction and medial rotation. The basic thoracic examination is usually negative.

Treatment is either by deep transverse friction or an infiltration with procaine (see Ch. 15).

Lesions of the diaphragm

A severe blow on the chest can be transmitted to the diaphragm, causing a sprain.

Pain is felt on respiration, and is not provoked or altered by movements of the trunk. In this condition, all movements of the trunk should be tested while the breath is fully held, because otherwise the patient may give false-positive responses related to respiration and not to the tests as such. When the central fibrous portion of the diaphragm is affected, pain is referred to the tip of the shoulder, whereas a lesion at the insertion at the ribs provokes more local pain at the lower margin of the thoracic cage.

Treatment

The peripheral costal insertion can be treated by deep transverse friction.

Technique: friction (Fig. 10)

The patient adopts a half-lying position and fully relaxes the abdominal muscles. The therapist sits at the patient’s painful side. The lesion is palpated at the inner side of the lower ribs. The fingertips of three or four fingers are hooked under them. Friction is obtained by a movement parallel to the rib, meanwhile applying anterior pressure against its posterior aspect.

Lesions of the abdominal muscles

Pain in the abdomen is usually the result of a visceral disorder. Exceptionally it arises from a musculoskeletal lesion, most frequently a thoracic or lumbar disc problem giving rise to segmental or extrasegmental referred pain.

Local muscular problems of the abdominal wall may also occur. They are usually encountered in athletes, very often soccer players. Pain is usually under the influence of movement and local pressure, sometimes of lifting and coughing. When this type of lesion is suspected, resisted flexion and rotations of the trunk must be checked. Active extension or active contralateral side flexion of the trunk can also be painful as the muscle is stretched. If, after a complete examination, the differential diagnosis between a visceral and a muscular problem remains unclear, palpation with the abdominal muscles relaxed is compared with palpation with the muscles in contraction. Greater pain on palpation with the muscles relaxed points towards a visceral problem, the opposite to a lesion of the abdominal muscles (Cyriax:20 p. 219; Ramboer and Verhamme35).

Lesions of the rectus abdominis muscle

These are usually located in the most distal 4 cm of the muscle belly, just above the pubic symphysis. The patient complains of local suprapubic pain during activity.

Pain is found on resisted anteflexion of the trunk and on active trunk extension. Bringing the patient’s ipsilateral arm upwards and backwards during active extension of the trunk increases the pain because of further stretching of the rectus muscle.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes lesions of the rectus femoris or the psoas muscles and osteitis pubis (see the online chapter Groin pain). In the former two, the pain lies more laterally and is also provoked by resisted flexion of the hip which provides the diagnostic key. In osteitis pubis the pain is at the pubic symphysis and is also provoked by resisted adduction of the hips. The fact that the pain is reproduced during the examination of both lower extremities should help in the differentiation.45,46

Treatment

An infiltration of 10–20 ml 0.5% procaine is normally curative.35 Deep friction is also effective.

Technique: injection (Fig. 11)

A 4 cm needle is fitted to a 10–20 ml syringe filled with 0.5% procaine. The patient is put in the half-lying position, keeping the abdominal muscles well relaxed. The tender part of the muscle is taken between thumb and index finger and the needle thrust in obliquely in a caudal direction. Special care must be taken not to push the needle in too deeply. With several withdrawals and reinsertions the procaine is infiltrated.

The patient is reassessed 1 week later. If full cure has not been achieved, a second infiltration is given. Three infiltrations may be necessary.

Technique: deep friction (Fig. 12)

The patient is put in the half-lying position with the abdomen well relaxed. The therapist sits at the painless side and places two or three fingers on the tender spot. Counterpressure is taken with the thumb. Friction is a to-and-fro movement by flexion–extension of the elbow.

The oblique muscles

A sprain of one of the oblique muscles gives rise to pain in the anterolateral part of the abdomen. Pain is provoked or increased by resisted rotation of the trunk: pain on resisted rotation away from the painful side signifies a lesion of the external oblique muscle; pain on resisted rotation towards the painful side originates from the internal oblique muscle.

Stretching the affected fibres also hurts. Consequently active extension of the trunk or active side flexion towards the painless side is also likely to be painful.

The lesion can lie either at the costal origin or in the muscle belly. In the former, palpation should be done at the inferoposterior margin of the ribs, with the finger pressing against the internal aspect of the rib for the internal oblique muscle or against the external aspect for the external oblique muscle.

Treatment

A lesion at the origin of the external oblique muscle or in the muscle belly is treated by deep transverse friction. The origin at the ribs of the internal oblique muscle can be treated only by deep friction, using the same technique as for the costal origin of the diaphragm (see above).

Technique: deep friction to the muscle belly (Fig. 13)

The patient is put in a half-lying position with the therapist sitting at the side opposite to the lesion. The tips of two or three fingers are placed on the painful area. Friction is given by a flexion–extension movement at the elbow, transverse to the direction of the fibres – i.e. in the direction contralateral shoulder–ipsilateral hip.

Each session takes about 15 minutes. Cure is normally obtained in about 10–15 sessions.

References

1. Master, A, The spectrum of anginal and noncardiac chest pain. JAMA 1964; 187:894–899. ![]()

2. Rawlings, M, Differential diagnosis of painful chest. Geriatrics 1963; Feb:139–150. ![]()

3. Erb, B, Tullis, I, Dissecting aneurysm of the aorta. Circulation 1960; 22:315. ![]()

4. Metlay, JP, Kapoor, WN, Fine, MJ, Does this patient have community-acquired pneumonia? Diagnosing pneumonia by history and physical examination. JAMA 1997; 278:1440–1445. ![]()

5. Haber, SE, Haber, JM, Malignant mesothelioma: a clinical study of 238 cases. Ind Health 2010; . ![]()

6. Borasio, P, Berruti, A, Billé, A, Giaj Levra, M, Giardino, R, Ardisonne, F, Malignant pleural mesothelioma: clinicopathologic and survival characteristics in a consecutive series of 394 patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008; 33:307–313. ![]()

7. Harley, RA, Pathology of pleural infections. Semin Respir Infect 1988; 3:291–297. ![]()

8. Huang, WT, Lee, PI, Chang, LY, et al, Epidemic pleurodynia caused by coxsackievirus B3 at a medical center in northern Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2010;43(6):515–518. ![]()

9. Hull, RD, Raskob, GE, Carter, CJ, et al, Pulmonary embolism in outpatients with pleuritic chest pain. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148(4):838–844. ![]()

10. Kumar, P, Clark, M. Clinical Medicine, 3rd ed. London: Baillière Tindall; 1994.

11. Bernard Bagattini, S, Bounameaux, H, Perneger, T, Perrier, A, Suspicion of pulmonary embolism in outpatients: nonspecific chest pain is the most frequent alternative diagnosis. J Intern Med. 2004;256(2):153–160. ![]()

12. Spengler, D, Kirsh, M, Kaufer, H, Arbor, A, Orthopaedic aspects and early diagnosis of superior sulcus tumour of lung (Pancoast). J Bone Joint Surg. 1973;55A(8):1645–1650. ![]()

13. Brown, C, Compressive, invasive referred pain to the shoulder. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1983; 173:55–62. ![]()

14. Bisbinas, I, Langkamer, VG, Pitfalls and delay in the diagnosis of Pancoast tumour presenting in orthopaedic units. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1999;81(5):291–295. ![]()

15. Demaziere, A, Wiley, AM, Primary chest wall tumor appearing as frozen shoulder. Review and case presentations. J Rheumatol. 1991;18(6):911–914. ![]()

16. Dartevelle, P, Macchiarini, P, Surgical management of superior sulcus tumors. Oncologist. 1999;4(5):398–407. ![]()

17. Johnson, DE, Goldberg, M, Management of carcinoma of the superior pulmonary sulcus. Oncology. 1997;11(6):781–785. ![]()

18. Pedersen, J, Reddy, H, Funch-Jensen, P, Arendt-Nielsen, L, Gregersen, H, Drewes, AM, Cold and heat pain assessment of the human oesophagus after experimental sensitisation with acid. Pain. 2004;110(1–2):393–399. ![]()

19. Grosbois, B, Pawlotsky, Y, Chales, G, Meadeb, J, Carsin, M, Louboutin, J, Etude clinique et radiologique de l’articulation manubriosternale. Rev Rhum 1981; 48:495. ![]()

20. Sebes, J, Salazar, J, The manubriosternal joint in rheumatoid disease. Am J Rheumatol 1983; 140:117. ![]()

21. Cyriax, J. Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, vol I, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions, 8th ed. London: Baillière Tindall; 1982.

22. Goei The, HS. The Clinical Spectrum of Chronic Inflammatory Back Pain in Hospital Referred Patients. Voerendaal: Rijksuniversiteit Leiden Drukkerij Schrijen-Lippertz BV; 1987.

23. Proulx, AM, Zryd, TW, Costochondritis: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80(6):617–620. ![]()

24. Kayser, H, Tietze’s syndrome: a review of the literature. Am J Med 1956; 21:982–989. ![]()

25. Düben, W, Das Tietzesyndrom und seine differentialdiagnostische Bedeutung. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1952; 77:872–875. ![]()

26. Honda, N, Machida, K, Mamiya, T, Takahashi, T, et al, Scintigraphic and CT findings of Tietze’s syndrome: report of a case and review of the literature. Clin Nucl Med. 1989;14(8):606–609. ![]()

27. Disla, E, Rhim, HR, Reddy, A, Karten, I, Taranta, A, Costochondritis. A prospective analysis in an emergency department setting. Arch Inter Med. 1994;154(21):2466–2469. ![]()

28. Jelenko, C, Tietze’s syndrome at the xiphisternal joint. South Med J 1974; 67:818–820. ![]()

29. Kamel, M, Kotob, H, Ultrasonographic assessment of local steroid injection in Tietze’s syndrome. Br J Rheumatol. 1997;36(5):547–550. ![]()

30. Choi, YW, Im, JG, Song, CS, Lee, JS, Sonography of the costal cartilage: normal anatomy and preliminary clinical application. J Clin Ultrasound. 1995;23(4):243–250. ![]()

31. Gray, R, Gottlieb, N, Intra-articular corticosteroids. An updated assessment. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1983; 177:236–263. ![]()

32. Dunlop, R, Tietze revisited. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1969; 62:223–225. ![]()

33. Cyriax, EF. On various conditions that may simulate the referred pains of visceral disease, and a consideration of these from the point of view of cause and effect. Practitioner. 1919; 102:314–322.

34. McBeath, A, Keene, J, The rib-tip syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg. 1975;57A(6):795–797. ![]()

35. Ramboer, C, Verhamme, M. Abdominale Wandpijn. Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1993; 49(7):445–449.

36. Broadhust, N, Musculoskeletal medicine tip: twelfth rib syndrome. Aust Fam Physician 1995; 24:1516. ![]()

37. Scott, EM, Scott, BB, Painful rib syndrome – a review of 76 cases. Gut. 1993;34(7):1006–1008. ![]()

38. Barki, J, Blanc, P, Michel, J, et al, Painful rib syndrome (or Cyriax syndrome). Study of 100 patients. Presse Med. 1996;25(21):973–976. ![]()

39. den Dunnen, WF, Verbeek, PC, Karsch, AM, Abdominal pain due to nerve compression. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1999;143(11):576–578. ![]()

40. Marin, I, Lepresle, C, Mechet, MA, Debesse, B, Postoperative pain after thoracotomy. A study of 116 patients. Rev Mal Respir. 1991;8(2):213–218. ![]()

41. Kalso, E, Perttunen, K, Kaasinen, S, Pain after thoracic surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1992;36(1):96–100. ![]()

42. Perttunen, K, Tasmuth, T, Kalso, E, Chronic pain after thoracic surgery: a follow-up study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1999;43(5):563–567. ![]()

43. Skubic, J, Kostuik, J. Thoracic pain syndromes and thoracic disc herniation. In: The Adult Spine. Principles and Practice. New York: Raven Press; 1991:1443–1461.

44. Marcove, R, Chondrosarcoma: diagnosis and treatment. Orthop Clin North Am. 1977;8(4):1443–1461. ![]()

45. Fricker, PA, Taunton, JE, Ammann, W, Osteitis pubis in athletes. Infection, inflammation or injury? Sports Med. 1991;12(4):266–279. ![]()

46. Briggs, RC, Kolbjornsen, PH, Southall, RC, Osteitis pubis, Tc-99m MDP, and professional hockey players. Clin Nuci Med. 1992;17(11):861–863. ![]()