Disorders of the skin

Introduction

Only a small proportion of skin disorders is surgically important. These include unsightly lesions, lumps and possible malignant lesions. Ulcers of the lower limb are common and usually of vascular or diabetic neural and/or ischaemic origin. Some venous ulcers are managed by dermatologists, but many are managed by surgeons and specialist nurses; these are discussed in Chapter 43. Ulceration is also a characteristic of many malignant skin lesions.

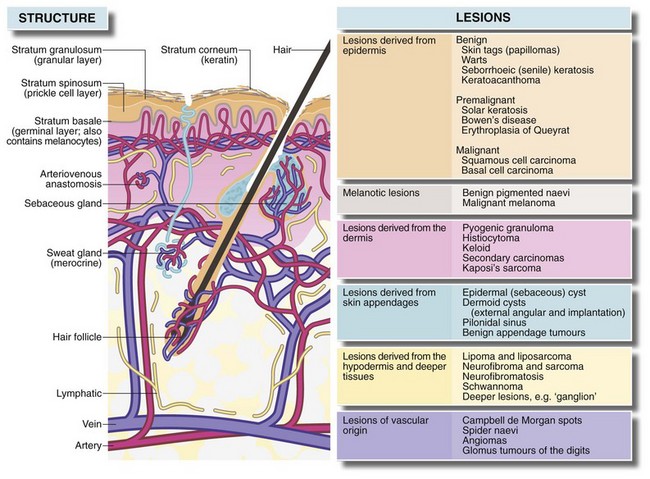

Structure of normal skin (Fig. 46.1)

The skin has three main layers, epidermis, dermis and hypodermis:

• The epidermis has four layers—basal, prickle-cell, granular and keratin. Cell division normally occurs only in the basal layer

• The dermis consists of dense, tough interlacing collagen fibres; their orientation determines lines of skin tension known as Langer’s lines. These are surgically important because incisions parallel to them heal with minimal scarring

• The deepest layer of the skin is the hypodermis, consisting of loose fibro-fatty tissue and containing skin appendages—sweat glands, hair follicles and associated sebaceous glands. The skin is generally mobile over deeper structures because the hypodermis is only loosely connected to the superficial fascia, but is tightly bound to fascia in the palms, the soles of the feet and the scalp.

Symptoms and signs of skin disorders

In practice (and in clinical exams) skin lesion diagnosis rarely follows the pattern of history, examination and investigation. Rather, the lesion is thrust before the doctor’s eyes and a ‘spot’ or differential diagnosis is made. History and examination then help confirm the diagnosis or narrow the possibilities. Table 46.1 summarises the clinical features of skin lesions and their diagnostic significance.

Table 46.1

Symptoms and signs of skin disorders

| Symptoms and signs | Diagnostic significance |

| 1. Lump in or on the skin Size, shape and surface features Revealed by inspection—is the lesion smooth-surfaced, irregular, exophytic (i.e. projecting out of the surface)? |

Epidermal lesions such as warts usually have a surface abnormality but deeper lesions are usually covered by normal epidermis. A punctum suggests the abnormality arises from an epidermal appendage, e.g. epidermal (sebaceous) cyst |

| Depth within the skin Superficial and deep attachments Which tissue is the swelling derived from? |

Tends to reflect the layer from which lesion is derived and therefore the range of differential diagnosis (i.e. epidermis, dermis, hypodermis or deeper) |

| Character of the margin Discreteness, tethering to surrounding tissues, three-dimensional shape |

A regular shaped, discrete lesion is most likely cystic or encapsulated (e.g. benign tumour). Deep tethering implies origin from deeper structures (e.g. ganglion). Immobility of overlying epidermis suggests a lesion derived from skin appendage (e.g. epidermal cyst) |

| Consistency Soft, firm, hard, ‘indurated’, rubbery |

Soft lesions are usually lipomas or fluid-filled cysts. Most cysts are fluctuant unless filled by semi-solid material (e.g. epidermal cysts), or the cyst is tense (e.g. small ganglion) Malignant lesions tend to be hard and irregular (‘indurated’) with an ill-defined margin due to invasion of surrounding tissue Bony-hard lesions are either mineralised (e.g. gouty tophi) or consist of bone (e.g. exostoses) |

| Pulsatility | Pulsatility is usually transmitted from an underlying artery which may simply be tortuous or may be abnormal (e.g. aneurysm or arteriovenous fistula) |

| Emptying and refilling | Vascular lesions (e.g. venous malformations or haemangiomas) empty or blanch on pressure and then refill |

| Transilluminability | Lesions filled with clear fluid such as cysts ‘light up’ when transilluminated |

| Temperature | Excessive warmth implies acute inflammation, e.g. pilonidal abscess |

| 2. Pain, tenderness and discomfort | These symptoms often indicate acute inflammation. Pain also develops if a non-inflammatory lesion becomes inflamed or infected (e.g. inflamed epidermal cyst). Malignant lesions are usually painless |

| 3. Ulceration (i.e. loss of epidermal integrity with an inflamed base formed by dermis or deeper tissues) | Malignant lesions and keratoacanthomas tend to ulcerate as a result of central necrosis. Surface breakdown also occurs in arterial or venous insufficiency (e.g. ischaemic leg ulcers), chronic infection (e.g. TB or tropical ulcers) or trauma, particularly in an insensate foot |

| Character of the ulcer margin | Benign ulcers—the margin is only slightly raised by inflammatory oedema. The base lies below the level of normal skin Malignant ulcers—these begin as a solid mass of proliferating epidermal cells, the centre of which eventually becomes necrotic and breaks down. The margin is typically elevated ‘rolled’ and indurated by tumour growth and invasion |

| Behaviour of the ulcer | Malignant ulcers expand inexorably (though often slowly), but may go through cycles of breakdown and healing (often with bleeding) |

| 4. Colour and pigmentation Normal colour |

If a lesion is covered by normal-coloured skin then the lesion must lie deeply in the skin (e.g. epidermal cyst) or deep to the skin (e.g. ganglion) |

| Red or purple | Redness implies increased arterial vascularity, which is most common in inflammatory conditions like furuncles. Vascular abnormalities which contain a high proportion of arterial blood such as Campbell de Morgan spots or strawberry naevi are also red, whereas venous disorders such as port-wine stain are darker. Vascular lesions blanch on pressure and must be distinguished from purpura which does not |

| Deeply pigmented | Benign naevi (moles) and their malignant counterpart, malignant melanomas, are nearly always pigmented. Other lesions such as warts, papillomata or seborrhoeic keratoses may become pigmented secondarily. Hairy pigmented moles are almost never malignant. Rarely, malignant melanomas may be non-pigmented (amelanotic). New darkening of a pigmented lesion should be viewed with suspicion as it may indicate malignant change |

| 5. Rapidly developing lesion | Keratoacanthoma, warts and pyogenic granuloma may all develop rapidly and eventually regress spontaneously. When fully developed, these conditions may be difficult to distinguish from malignancy. Spontaneous regression marks the lesion as benign |

| 6. Multiple, recurrent and spreading lesions | In certain rare syndromes, multiple similar lesions develop over a period. Examples include neurofibromatosis and recurrent lipomata in Dercum’s disease. Prolonged or intense sun exposure predisposes a large area of skin to malignant change. Viral warts may appear in crops. Malignant melanoma may spread diffusely (superficial spreading melanoma) or produce satellite lesions via dermal lymphatics |

| 7. Site of the lesion | Some skin lesions arise much more commonly in certain areas of the body. The reason may be anatomical (e.g. pilonidal sinus, external angular dermoid or multiple pilar cysts of the scalp) or because of exposure to sun (e.g. solar keratoses or basal cell carcinomas of hands and face) |

| 8. Age when lesion noticed | Congenital vascular abnormalities such as strawberry naevus or port-wine stain may be present at birth. Benign pigmented naevi (moles) may be detectable at birth, but only begin to enlarge and darken after the age of 2 |

History and examination

The lesion is examined in detail, looking for the points in Table 46.1. General clinical examination searches for other similar lesions, regional lymphadenopathy or a primary malignancy arising elsewhere and metastasising to skin. For example, if inguinal lymph nodes are enlarged, rectal and genital examination should be carried out to exclude concealed carcinoma. The lower limbs, including the soles of the feet, should also be examined for malignant melanoma.

Principles of managing skin lesions

Many skin lesions can be diagnosed from the history and clinical examination, but where there is doubt, biopsy is needed, particularly if there is risk of malignancy. Excision biopsy is treatment if the lesion is small. Incision and excision biopsy techniques are illustrated in Chapter 10, p. 136 and Box 46.1 summarises surgical options for skin conditions.

Lesions originating in the epidermis

Seborrhoeic keratosis

Seborrhoeic keratoses (seborrhoeic warts) are very common in elderly patients but occasionally appear in younger people (Fig. 46.2). They are most common on the trunk, face, neck and arms, often with many different sized lesions with varying pigmentation. They may be up to several centimetres in diameter. The lesions are slightly raised, sharply demarcated and plaque-like; they look and feel irregular and waxy. Darkly pigmented lesions cannot be distinguished clinically from superficial spreading malignant melanomas.

Keratoacanthoma

Keratoacanthoma is a nodular, single skin lesion, up to 2 cm across (Fig. 46.3b, c). They have an irregular central crater containing keratotic debris. The histological lesion consists of localised tumour-like epidermal proliferation, with a thick prickle cell layer (acanthosis) and marked keratinisation. Some epithelial cells are large with atypical nuclei; the underlying dermis exhibits chronic inflammatory cell infiltration.

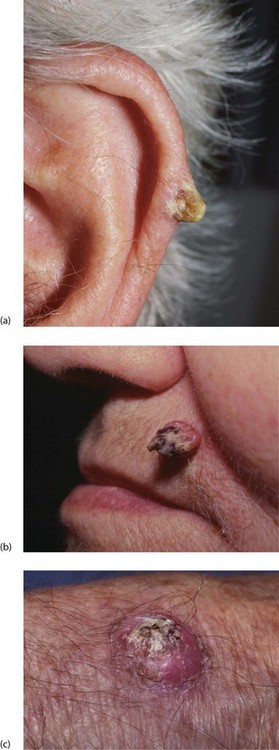

Fig. 46.3 Keratin horn and keratoacanthoma

(a) Keratin horn on the pinna of an elderly man. If untreated, these can grow large.

(b) This alarming looking lesion is a benign keratoacanthoma. The central keratin plug is characteristic. Resolution is spontaneous after a few weeks.

(c) Similar lesion on the back of the hand. Squamous and basal cell carcinoma need to be excluded

Melanotic lesions

Benign naevi: Deeper layers of the epidermis contain scattered melanocytes that synthesise melanin which is transferred to nearby epidermal cells where it is responsible for skin colour. Melanocyte concentration is similar in all races but pigmentation depends on the quantity of melanin produced. Although skin colour is determined mainly by genetic factors, it is enhanced by exposure to ultraviolet rays of sunlight (tanning).

Lentigo: Lentigines (the plural of lentigo) are benign pigmented lesions that feature in the differential diagnosis of melanotic lesions. They are large, heavily pigmented patches on the face and hands of the elderly. Melanocytes are numerous, and melanin production is excessive but there is no accumulation of naevus cells. Lentigines are benign but predispose to superficial spreading malignant melanoma.

Premalignant and malignant epidermal conditions

Solar (senile) keratosis and intra-epidermal carcinoma

Pathology and clinical features: Solar keratoses are flat, well-demarcated, brown, scaly or crusty lesions with an erythematous base (Fig. 46.4). They bleed easily if traumatised or scratched. Solar keratoses are often multiple and are most common in later life on sun-exposed parts such as face, neck, arms and hands. The incidence is higher in farm workers, fishermen and other outdoor workers. Solar keratoses are especially common in fair-skinned people living in tropical or subtropical regions like Australia or the southern USA.

Management: Management depends on number, size and distribution, age of the patient, and whether the skin type predisposes to cancer. Isolated lesions are best excised. For multiple keratoses, excision biopsy of representative lesions is performed initially to confirm the diagnosis, followed by topical 5-fluorouracil cream, diclofenac gel or imiquimod cream, or by excision biopsy, curettage or cryotherapy of suspicious lesions. Patients should be repeatedly advised to minimise exposure to UV rays by wearing protective clothing and hats and applying high factor total (UVA + UVB) sunscreen creams. Patients should be regularly examined for squamous cell carcinomas, basal cell carcinomas and melanomas, all more common with marked sunshine exposure.

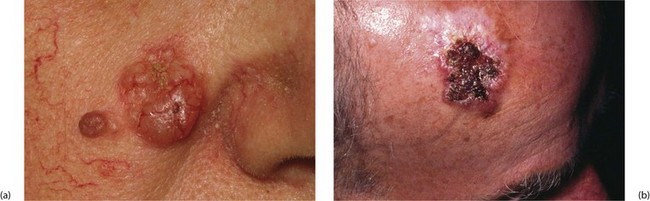

Squamous cell carcinoma

Pathology: Squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs, Fig. 46.5) occur anywhere on the skin or stratified squamous epithelium of the mouth, tongue, oesophagus, anal canal, glans penis or uterine cervix. Squamous cell carcinoma also occurs in metaplastic squamous epithelium in bronchus, oesophagus or bladder.

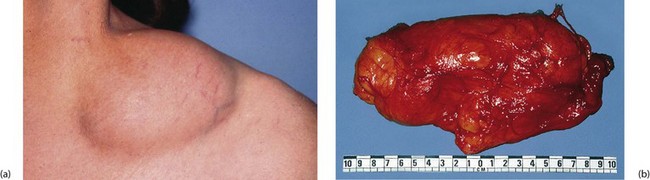

Fig. 46.5 Squamous carcinoma

(a) This 70-year-old farmer had worked in the fields exposed to the sun all his life. He presented with this obviously malignant lesion on the upper part of the pinna. It was confirmed on biopsy to be a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (b) after local resection

Clinical presentation: Squamous cell carcinoma usually presents as an enlarging painless ulcer with a rolled, indurated (hardened) margin. Other lesions have an exophytic (outward growing, proliferative) cauliflower-like appearance with areas of ulceration, bleeding or serous exudation. SCCs invade the dermis and deeper tissues such as bone or cartilage; further spread is usually to regional lymph nodes. Distant metastases are relatively uncommon.

Management of squamous cell carcinoma: Management involves first confirming the diagnosis by biopsy, then local radiotherapy or excision with a margin of normal tissue. For certain SCCs, including recurrences, at sites where conserving normal tissue is important for cosmetic or functional reasons, as well as for SCCs whose edges cannot be clearly defined, a special technique known as Mohs’ micrographic surgery is often employed. Under local anaesthesia, this involves frozen section histology of sequential horizontal sections. If malignant cells remain, further sections are removed until clear of malignancy.

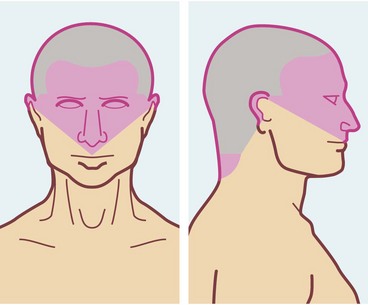

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC)

Pathology and clinical features: Basal cell carcinomas are common and nearly always result from exposure to excess ultraviolet in sunlight. White-skinned people in tropical and sub-tropical regions have an extremely high incidence, with up to 50% affected at some time, often with multiple lesions. As with SCCs, basal cell carcinomas usually develop from middle age onwards, but incidence is rising in younger ‘sun-worshippers’. Males are affected at least twice as often as females, reflecting greater occupational and recreational exposure to the sun.

Most BCCs arise on the upper part of the face (Figure 46.6), although any part of the skin can be involved. Most patients present early because lesions are so visible.

Basal cell carcinomas begin as small pearly-white nodules with visible telangiectatic blood vessels (Fig. 46.7). Early lesions may ulcerate, bleed and then heal again, but eventually they form irregular ulcers (rodent ulcers) with a pearly rolled margin. Although BCCs almost never metastasise they are definitely malignant, and will invade underlying bone and cartilage. Neglected lesions on the scalp or neck may even invade brain or spinal cord.

Management of basal cell carcinomas: Small lesions are usually treated by cryotherapy without histology. Other treatments include topical chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil or imiquimod cream, local radiotherapy or 2–3 cycles of curettage combined with electrocautery. Excision biopsy may be appropriate for isolated or suspicious lesions. Radiotherapy must be used with caution on nose or ear where cartilage is susceptible to radiotherapy damage and may undergo necrosis. Larger destructive lesions usually require reconstructive plastic surgery involving skin grafts or flaps.

Malignant melanoma

Introduction and pathology: Malignant melanoma (Fig. 46.8) arises by malignant transformation of melanocytes. Most are poorly differentiated, with numerous mitotic figures, and the presence of melanin is diagnostic. Suspected amelanotic (non-pigmented) melanomas may need to be confirmed by immunohistochemical tests.

Risk factors: The epidemiology of malignant melanoma is fascinating. About 80% occur in white-skinned people and the disease is extremely common in albinos of all races. Until recently, malignant melanoma was rare in northern Europe but the incidence has risen sharply over the last three decades. About 1 in 100 Americans will be affected some time in their lives. The highest incidence is in northern and western Australia and it is certain ultraviolet radiation is the essential aetiological factor. Whilst cumulative sun is the main factor for other skin malignancies, short periods of intense exposure causing blistering sunburn appear to be more important for malignant melanoma. There is evidence that unaccustomed exposure to strong sunlight can suppress general immunological responses and, by implication, immunological tumour surveillance. This might explain malignant melanomas on skin not generally exposed to the sun, for example the soles of the feet or anal canal.

Melanoma subtypes: Melanomas may be classified as growing radially (superficial spreading type) or vertically (nodular type). About 80% are the superficial spreading type. These grow slowly and usually arise in pre-existing pigmented naevi. Lesions are flat with a variegated border, often with patches of regression. Nodular melanomas are more common in men. They demonstrate an early vertical growth phase and develop more rapidly and behave more aggressively; they tend to arise in normal skin. Five per cent of nodular melanomas are amelanotic.

Acral melanoma occurs on the palms or soles or under the nails. This is the only type found in dark-skinned individuals and has a low incidence in white people. They occur at a mean age of 60 (see Fig. 46.19 below). Malignant melanomas in less obvious areas have a reputation for aggressive behaviour but this may be because of late diagnosis.

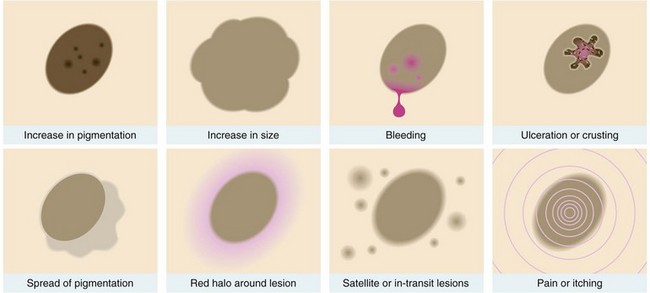

Clinical features of malignant melanoma: Most malignant melanomas are black or dark brown, flat or nodular lesions which may bleed or ulcerate. If a pre-existing or new mole enlarges, darkens, bleeds or becomes inflamed, ulcerated or itchy, it should be regarded with great suspicion (see Fig. 46.9). Superficial spreading melanoma can easily be mistaken for a pigmented seborrhoeic keratosis. In general, spread to regional lymph nodes occurs early. Lateral spread in dermal lymphatics may produce satellite lesions around the primary nodule and ‘in transit’ lesions may appear along the course of the lymph node drainage.

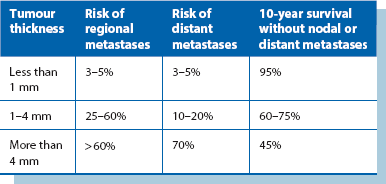

Prognostic factors: Measured tumour thickness on histological examination (Breslow) is the most useful guide to prognosis (Table 46.2) and has proved more accurate than the older ‘Clark’s level of invasion’. Tumour thickness correlates well with the likelihood of regional and distant metastases (Table 46.2). Other factors affecting prognosis include:

Table 46.2

Risk of regional and distant metastasis in malignant melanoma according to Breslow thickness

• The presence of ‘satellite lesions’ around the primary or ‘in transit’ lesions between primary and lymph node field—make the prognosis worse

• Ulceration of the primary lesion—increases likelihood of metastases and reduces survival

• Site of primary—head lesions carry a worse prognosis

• Gender—with thick lesions, females fare better than males

• Pathological stage—nodal or distant involvement. The number and size of lymph node metastases affects survival—a single positive node is associated with a 40% 10-year survival, falling to 13% with two or more positive. If distant metastases are present, 2-year survival is only 25%

• Certain histopathological characteristics (e.g. high mitotic rate) indicate poorer prognosis

Management of malignant melanoma: The first aim with a pigmented lesion is to establish whether it is malignant. Unless malignancy is clinically obvious, small lesions should be removed by excision biopsy and more extensive lesions sampled by incision biopsy. As a result of controlled trials, there have been two major changes in managing the local lesion. Firstly, it is no longer necessary to excise the lesion with a 5 cm margin all around and, secondly, split skin grafting is no longer regarded as essential to achieve skin cover and provide early warning of local recurrence. For melanomas less than 1 mm thick, a clear margin of 1 cm is sufficient. For thicker melanomas (1.1–4 mm), excision with 2 cm clearance achieves optimum survival. For lesions thicker than 4 mm, a 3 cm clearance is believed desirable. Primary closure or the use of local rotational flaps can usually achieve skin cover.

Lesions originating in the dermis

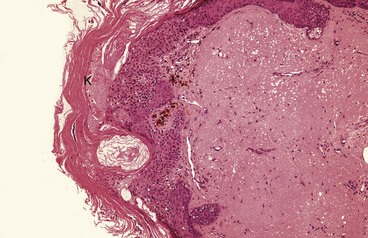

Epidermal cysts: These are by far the most common skin cysts, and are often incorrectly described as ‘sebaceous cysts’. Usually solitary, they may be found anywhere on the body (except the palms or soles), most commonly scalp, trunk, face and neck. They range up to several centimetres in diameter. Epidermal cysts are smooth and rounded, and covered by normal epidermis in which a blocked duct (punctum) may be visible. On palpation, they have a doughy, fluctuant consistency and are not usually tender. An important clinical diagnostic feature is that since they originate in skin, they are attached to it but are mobile over deeper tissues. Multiple small epidermal cysts sometimes develop on the scrotal skin or areola and cause embarrassment.

Surgical removal (see Ch. 10): Epidermal cysts are mainly removed because of recurrent inflammation. Others are removed for cosmetic reasons or sometimes because they interfere with clothing or hair combing. An incision is made over the cyst beside and around the punctum, taking care not to puncture the cavity. The cyst is enucleated by blunt dissection and delivered in its entirety. This ensures all lining epithelium is removed and prevents recurrence.

Inflamed epidermal cysts: Trauma to epidermal cysts (often unnoticed) may cause some contents to escape into surrounding tissues, eliciting an intense foreign-body inflammatory response. The patient may complain of pain, swelling, redness and even spontaneous discharge of liquefied cyst contents; this looks like pus but is sterile. These inflamed epidermal cysts are often described as ‘infected’ but this is rarely the case and antibiotic therapy is not indicated.

Infective lesions

(Note: not infective in aetiology)

Pyogenic granuloma (Fig. 46.10) is a common inflammatory skin lesion that arises in response to minor penetrating foreign bodies such as splinters or thorns. It usually develops over about a week and rarely regresses spontaneously. Lesions are most common on the hands and feet but may occur on lips or gums. Pathologically, there is a mass of exuberant granulation tissue containing numerous polymorphs.

Furuncle (boil) and carbuncle

A furuncle is a staphylococcal abscess that develops in a hair follicle in the dermis. Early lesions can be easily treated with topical fusidic acid. Diabetes mellitus can be a predisposing factor. The lesion rapidly enlarges and eventually ‘points’ at the surface, spontaneously discharging pus. The centre often contains a core of necrotic tissue. Once pus has discharged and the necrotic tissue shed, the lesion heals spontaneously; however, the necrotic core may need excising to speed healing. Drainage may be encouraged with poultices or dressings, such as magnesium sulphate paste, said to draw the pus to the surface by osmosis. Furuncles are most common in young men with acne, especially on the face, back of the trunk and lower limbs. Axillary furuncles are common in middle-aged females and tend to recur. Surgical drainage is necessary if a chronic abscess develops. A furuncle may be the source of systemic sepsis, especially in uncontrolled diabetes. Cavernous sinus thrombosis is a rare but very serious (and often fatal) complication of a furuncle on the lateral aspect of the nose or infra-orbital area. This area drains into the cavernous sinus via the facial vein and inferior ophthalmic veins (see Fig. 46.13).

A carbuncle, also staphylococcal, is larger than a furuncle and consists of a honeycomb of abscesses, often draining (inadequately) via multiple sinuses. The back (nape) of the neck is the usual site (Fig. 46.11); here the skin is tightly bound by interlacing bundles of fibrous tissue. Carbuncles are more likely to occur in diabetics, and may bring diabetes to light. Treatment is with anti-staphylococcal antibiotics such as flucloxacillin as early as possible. The aim is to minimise pus formation and necrosis that would lead to skin loss and delay healing. If pus has formed, thorough desloughing and drainage of the abscesses is required, usually leaving wounds open to heal by secondary intention.

Malignant lesions

Kaposi’s sarcoma

This once rare condition has leapt to prominence as one of the most frequent presentations of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) is associated with human herpes virus 8. The condition appears as multiple blueish-red to brown nodules or plaques, all of which are primary tumours (Fig. 46.12). They most commonly occur on the limbs. Excision biopsy confirms the diagnosis. KS tumours are characterised by proliferating dysplastic fibroblasts, accompanied by chronic inflammation, endothelial proliferation and haemorrhage. Treatment varies: classical type KS usually does not need treatment but larger lesions respond to radiotherapy. Endemic KS is treated by chemotherapy, and AIDS-related KS is controlled by highly active antiretroviral therapy.

Lesions of the hypodermis and deeper tissues

Any area of skin may develop cellulitis (Fig. 46.13), the organisms usually gaining entry via a traumatic or surgical wound, although a wound is not always found. Clinically, the skin is greatly thickened, tense, hot, red and painful; margins are fairly clearly demarcated from adjacent normal skin. Lymphatics draining the affected area become inflamed and lymphangitis develops. Inflamed lymphatics are visible as red streaks passing towards the regional lymph nodes, which are also swollen and tender (lymphadenitis). Systemic features such as fever and tachycardia indicate bacteraemia or even septicaemia.

Lipoma and liposarcoma

Lipomas are benign tumours of fat. They occur anywhere fat is normally present, most often in the hypodermis of trunk and limbs. The aetiology is unknown, although mild trauma may be a factor. Typically, they present on the forearms (often multiple), in the supraclavicular fossa (Fig. 46.14), over the deltoid muscle or over the scapula. Lipomas can also be found within the peritoneal cavity, including the bowel submucosa, and within muscles or joints. They may also sometimes arise beneath periosteum.

Ganglion

This extremely common and inappropriately named condition is a cyst-like lesion derived from the lining of a synovial joint, tendon sheath or embryological remnants of synovial tissue. The ‘cystic’ space does not usually communicate with the associated joint or tendon sheath, and like synovial joint cavities, is not lined by epithelium. It contains a colourless, gelatinous fluid. Ganglia present as superficial lumps, usually about 1–2 cm in diameter, though sometimes larger. They are most common on the dorsum of the forearm and hand (Fig. 46.15) and around the ankle. They are rarely painful but sometimes cause mechanical problems or interference with footwear. Ganglia are easily recognised by their smooth, hemispherical surface, and firm but slightly fluctuant ‘cyst-like’ consistency. The overlying skin is normal and mobile and the ganglion weakly transilluminable.

Lesions of vascular origin

Cystic hygroma

Cystic hygroma is a lymphangioma presenting as a lump in the neck, usually during childhood; it is described in more detail in Ch 47, p. 589. Characteristically, the lesion is highly transilluminable.

Disorders of the nails

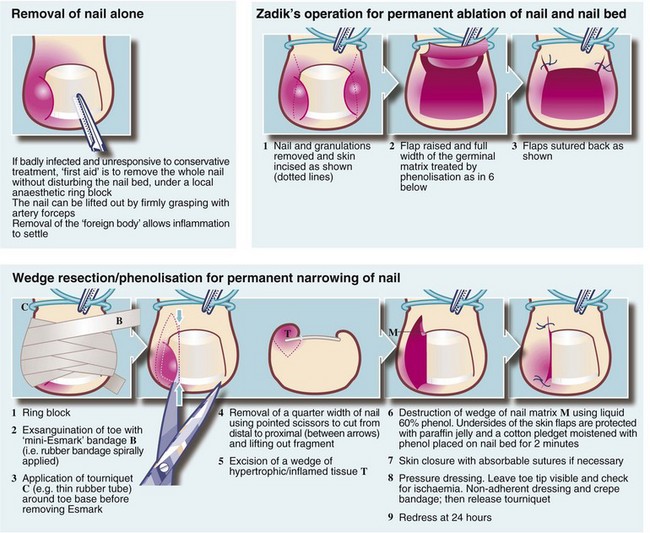

Ingrowing toenail

Pathophysiology: An ingrowing toenail (Fig. 46.16) occurs when the distal edge of the nail persistently cuts into the adjacent nail fold. The problem almost always affects the great toe. In effect there is a laceration which cannot heal because of the presence of a foreign body (the toenail). Superimposed infection by local bacterial and fungal flora complicates the picture. The combination of acute inflammation and attempts at repair produces exuberant granulation tissue around the laceration plus inflammatory swelling. Swelling aggravates trauma caused by the nail edge.

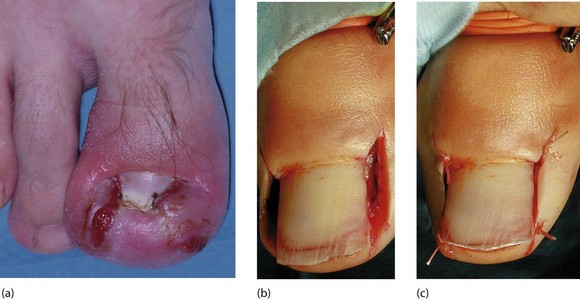

Fig. 46.16 Ingrowing toenail

(a) Inflamed ingrowing toenail affecting medial and lateral sides. There is a great amount of hypertrophy, making suitable footwear hard to find. (b) and (c) A different patient undergoing wedge resection and phenolisation of both sides of the nail. Note the use of a tourniquet

Management: The main objective of treatment is to prevent persistent trauma by the nail edge. Surgical operations result in a week or more of discomfort and immobility, so conservative treatment should be tried first.

Conservative treatment: In all cases, simple conservative measures include regular bathing, frequent changes of socks (which should be cotton), avoiding tight or narrow shoes and avoiding trauma to the toe when inflamed, for example from kicking a football.

Surgical treatment: Urgent surgical treatment involves avulsing the whole nail, or removing one side of it. This immediately removes the ‘foreign body’ and permits rapid resolution. For recurrent ingrowing toenails, particularly if abnormal nail morphology is contributory, part of the nail bed is best removed. Popular procedures are illustrated in Figure 46.17. Operations are usually performed under local anaesthesia using a ring block and tourniquet. Local anaesthetic incorporating a vasoconstrictor such as adrenaline (epinephrine) must never be used in digits because of the risk of ischaemic necrosis.

Onychogryphosis

Onychogryphosis (‘ram’s horn nail’) (Fig. 46.18) is a gross abnormality of nail growth. It affects the great toenail, which becomes thickened and distorted and nail cutting with ordinary nail scissors becomes impossible. Onychogryphosis is usually seen only in elderly patients and probably results from previous nail bed trauma. The condition usually presents when it interferes with wearing shoes. A chiropodist (podiatrist) can treat onychogryphosis with grinding instruments at regular intervals. Surgical removal of the nail and ablation of the bed is sometimes performed.

Subungual melanoma

Malignant melanomas sometimes develop beneath finger or toenails (Fig. 46.19). They are difficult to diagnose. Pigmented melanomas are easily mistaken for old subungual haematomas, and amelanotic melanomas appear even more innocuous, resembling pyogenic granulomas. Subungual melanomas often present early as a changing pigmented nail streak or longitudinal melanonychia. Advanced or clinically aggressive nail unit melanomas tend to present as a tumourous growth. Any suspicious lesion under the nail should be biopsied to avoid the disaster of missing a potentially curable malignant melanoma.