Disorders of the prostate

Anatomy

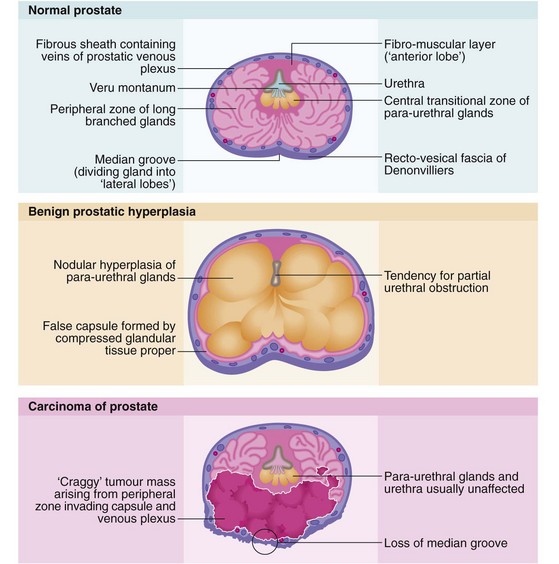

The normal prostate gland is about 3 cm long and 3 cm in diameter and weighs 10–15 g. The gland is situated immediately below the bladder neck so that the first 3 cm of the urethra lies within the gland (Fig. 35.1, p. 452) so the proximal urethral walls (the prostatic urethra) are composed of glandular tissue. The urethra then passes through the pelvic floor muscle that also constitutes the distal sphincteric mechanism. Prostatic hyperplasia or carcinoma may cause local urethral obstruction and carcinoma may invade and disrupt the sphincter mechanism.

The posterior aspect of the gland is palpable rectally (Fig. 35.1, pp. 450, 451) and a median groove can usually be identified. This groove is described as dividing the gland into two lateral lobes and tends to be obliterated in advanced prostatic cancer but is usually exaggerated in benign hypertrophy.

When the prostatic urethra is examined cystoscopically (see Fig. 35.3, p. 450), an important landmark is an elongated mound on the posterior wall known as the veru montanum (urethral crest), which can be variable in size and prominence. At its midpoint is a small depression, sometimes visible, into which the two ejaculatory ducts open. The posterior part of the gland above the ejaculatory ducts is known as the median lobe. If this becomes hypertrophied it may extend into the floor of the bladder (the surgical ‘middle lobe’); this may act as a flap valve and obstruct the bladder outlet.

As seen in Figure 35.1, the bulk of the normal prostate consists of up to 50 peripheral glandular lobules. These converge into about 20 separate ducts opening into the prostatic urethra lateral to the veru montanum. As well as this glandular tissue proper, there is a zone of small para-urethral glands adjacent to the urethra, the transition zone. From middle age onwards, the transition zone tends to enlarge to cause benign prostatic hyperplasia. At the same time, the peripheral glandular tissue is compressed to form a fibrous outer ‘surgical capsule’. In contrast, prostate cancer arises most often in the peripheral glandular tissue, tending to spread outwards into bordering structures more often than obstructing the centrally located urethra. Even after prostatectomy, cancer can arise in the residual peripheral zone.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia

Clinical features of benign prostatic hyperplasia

Symptoms and signs of bladder outflow obstruction (summarised in Box 35.1) are usually gradual in onset. Benign causes are prostatic hyperplasia and the apparently independent disorder of bladder neck hypertrophy and fibrosis. Acute retention of urine may occur suddenly at any time and is commonly precipitated by bladder overfilling after excessive fluid intake. It is also a hazard of many general surgical or orthopaedic operations on older men and also of any pelvic or perineal operations after adolescence. In some patients, the severity of prostatic symptoms fluctuates from month to month (and even perhaps with the season), making it difficult to decide whether an operation is necessary.

Complications of bladder outlet obstruction

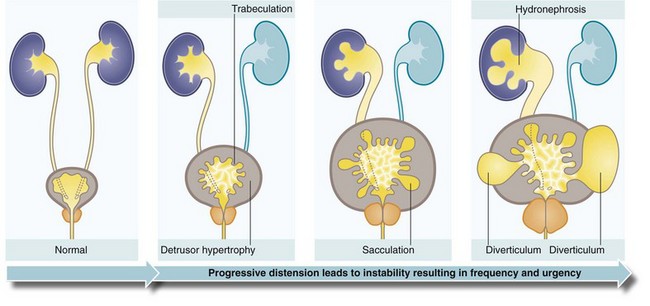

Prostatic obstruction can progressively interfere with the patient’s ability to empty his bladder but only 20–30% of patients have progressive symptoms and 50% remain unchanged over 5 years. In progressive cases, the volume of residual urine gradually increases over weeks and months (i.e. chronic retention) and in a minority leads to a rise in intravesical pressure. In the latter, the threshold for the voiding reflex is reached more quickly and calls to void become more frequent. The stagnant residual urine is prone to infection which exacerbates the symptoms. In chronic retention, the bladder becomes vastly distended and atonic, which can lead to overflow incontinence. In other cases, the detrusor muscle undergoes hypertrophy in an attempt to overcome the outflow obstruction. The normally smooth bladder lining then becomes trabeculated. Eventually, muscle fibre bundles are replaced by non-contractile fibrous tissue; this may explain why some patients fail to improve after obstruction is relieved. With a further rise in pressure, the depressions between the muscle bands deepen (sacculation) and eventually form bladder diverticula. Urinary stasis in the diverticula predisposes to stone formation (see Fig. 35.2).

Management of benign prostatic hyperplasia

The principles of management of bladder outlet obstruction believed to be due to benign prostatic hyperplasia are outlined in Box 35.2.

Diagnosis

A detailed history is first taken to assess the nature of the symptoms and how much they interfere with the patient’s life. The International Prostate Symptom Score sheet helps in assessing the overall impact of symptoms in a standardised way (Box 35.1). This, and the patient’s general condition, are the principal factors determining whether treatment is needed. The abdomen is examined for an enlarged bladder and the prostate palpated rectally. These clinical examinations, however, reveal only gross abnormalities.

Transurethral resection of prostate (TURP) and other transurethral treatments

The aim of transurethral prostatectomy is to remove the bulk of the prostate but leave the compressed normal peripheral tissue. This protects the subcapsular venous plexus that might otherwise bleed catastrophically. In TURP, a series of ‘chips’ or strips of tissue are excised with a resectoscope using a cutting diathermy wire loop; the chips drift into the bladder. The enlarged gland is progressively sliced away as shown in Figure 35.3, taking great care to preserve the sphincter mechanism immediately distal to the veru montanum. The prostatic chips are always examined histologically and may reveal unsuspected carcinoma. A transparent isotonic irrigation solution is used during the process, which washes away blood and debris to allow continuous visibility. Since some irrigation fluid is inevitably absorbed, sterile glycine solution is most often used instead of water as it does not cause haemolysis. If large volumes are absorbed, this causes dilutional hyponatraemia and hyperammonaemia along with drastic plasma electrolyte changes, producing the TUR syndrome. Various isotonic sugar solutions can now be safely used as alternatives.

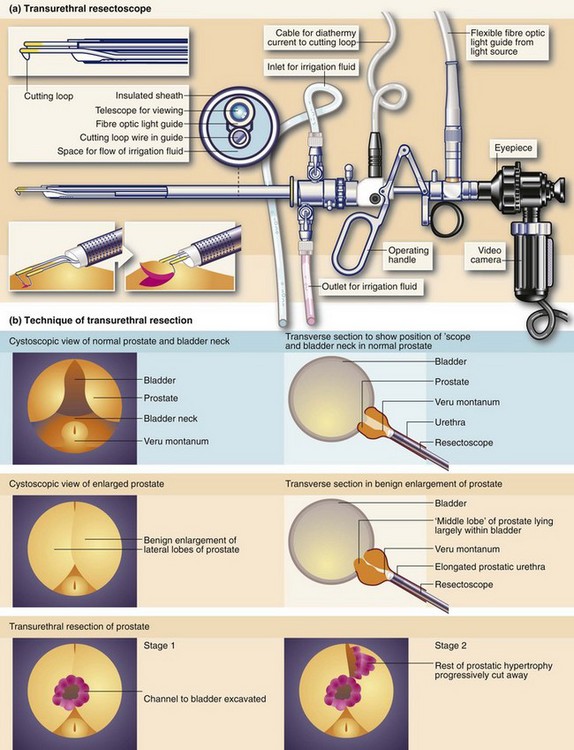

Fig. 35.3 Transurethral prostatectomy

(a) Transurethral resectoscope. ‘Divots’ or chips are cut by squeezing the handle towards the eyepiece while turning the diathermy current on. This ‘cheese-wires’ the cutting loop through tissue. (b) Technique of transurethral resection. (c) Ellik’s evacuator for bladder irrigation. The instrument is completely filled with irrigation fluid and then attached to the resectoscope sheath which is left in the bladder after withdrawal of the main instrument. Squeezing the bulb flushes fluid alternately in and out of the bladder, bringing the cut prostatic slices with it which then settle to the bottom of the container. (d) Apparatus for bladder irrigation in the postoperative period. The rate of fluid flow is adjusted to be fast enough to prevent clotting within the bladder. In practice the effluent should be pink rather than red. (e) Arresting haemorrhage after TURP. Excessive bleeding after transurethral resection can often be controlled by exerting traction on the catheter for 20 minutes (but not more). Tension is maintained by (i) tying a swab around the catheter, or (ii) attaching the catheter to the anterior abdominal wall with adhesive tape

Acute urinary retention and its management

Acute urinary retention may occur in patients with longstanding symptoms of bladder outlet obstruction; indeed in the majority of men with chronic retention, acute retention is the first presentation. It is often precipitated by overfilling of the bladder, faecal loading or urinary tract infection. Acute retention is a common cause of emergency surgical admission and a frequent early complication after any major operation, especially in males; it may therefore occur at any age even without bladder neck hypertrophy or prostatic enlargement. Management of postoperative acute retention is described in Chapter 11.

Catheterisation

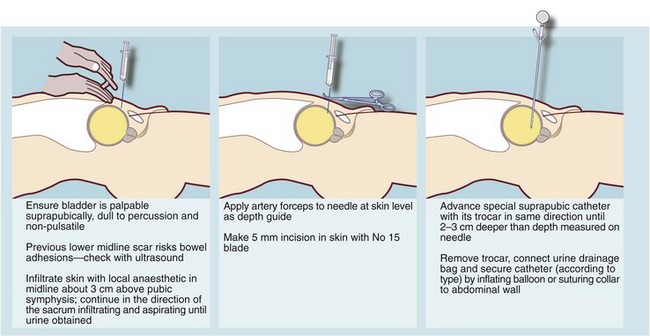

Acute retention is usually treated by urethral or preferably suprapubic catheterisation using an aseptic technique (Fig. 35.4). Urethral catheterisation may prove difficult in patients with a history of difficult catheterisation, prostatectomy or urethral stricture, or the finding of a non-retractile foreskin. If the problem appears complex, an experienced opinion should be sought early before risking urethral damage by unwise attempts at urethral catheterisation. Inserting a suprapubic catheter is quick and safe provided the bladder is palpably distended but should be avoided if there is a history of bladder tumour. A surgeon with urological training may elect to carry out cystourethroscopy and appropriate surgical treatment as a single scheduled procedure if catheterisation is not urgent.

Evaluating the underlying cause and any precipitating factors

‘Trial without catheter’

• A huge volume of retained urine released by catheterisation—indicating chronic retention

• Raised plasma urea and creatinine which improve after catheterisation—indicating chronic obstructive uropathy

• Previous episodes of acute retention

• Bladder outflow obstruction caused by carcinoma of prostate

• Acute retention in combination with a history of lower urinary tract symptoms sufficient in themselves to warrant surgery

Indwelling catheters and their management

Indications for permanent urethral or suprapubic catheterisation include:

• Patients unfit for prostatectomy

• Incontinent, elderly patients who are severely debilitated, demented or immobile

• Incontinence due to external sphincter damage caused by previous prostatectomy or invading carcinoma

Recurrent catheter blockage and infection are the major problems of long-term catheterisation. Catheters readily become blocked by epithelial debris or by gradual accretion of calculus. Modern silicone or silicone-coated ‘long-term’ catheters are better but must still be changed regularly every 10–12 weeks. In most cases, they can be changed at home by the GP or community nurse using full sterile precautions because if infection becomes established in the presence of a catheter, it is difficult to eradicate. However, low-grade infection is almost always present in elderly patients and causes little discomfort. Antibiotics should be prescribed only if local symptoms become troublesome or if systemic signs of infection develop.

Carcinoma of the prostate

Pathophysiology of prostatic carcinoma

The main prognostic indicators are the presenting PSA level, the PSA velocity (i.e. the rate at which it rises) and the histological grading. These factors have complicated the debate about the value of screening for prostatic cancer and the appropriateness of radical ‘curative’ surgery for localised asymptomatic disease. Prostate cancer screening has not been recommended in the UK or Australia. Even in the USA powerful national bodies have come out against it (see Ch. 6).

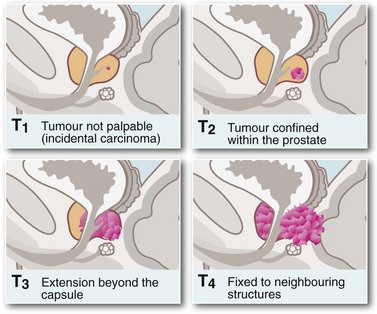

Symptoms and signs of prostatic cancer depend on the degree of local and systemic spread. Clinical staging is most commonly based on the TNM system (see Fig. 35.5). Incidence of pelvic lymph node involvement varies from 2% in T1 tumours to 85% in T5 tumours. The palpation characteristics of the malignant prostate are illustrated in Figure 35.1 (p. 446, 450).

Symptoms and signs of prostatic cancer

Rectal examination can sometimes reveal the primary diagnosis. On palpation of a T1 tumour, the prostate appears normal or smoothly enlarged by benign hyperplasia; stage T2 typically presents with a nodular, asymmetrical surface, and stage T3 with a large, hard, irregular gland with evidence of extension beyond the capsule or into the seminal vesicles. A tumour fixed to bone or adjacent pelvic organs is stage T4. Local spread may involve the rectum (causing changes in bowel habit) or the bladder neck and ureters (causing incontinence, impotence or rarely obstructive renal failure). At this late stage, the tumour is obvious on rectal palpation. In very advanced cases where cancer has invaded laterally to involve the pelvic walls or encircle the rectum, the pelvis may appear ‘frozen’ solid with tumour. Some patients develop major deep venous thrombosis affecting the lower limb. Modes of presentation of carcinoma of the prostate are summarised in Box 35.3.

Approach to investigation of suspected prostatic carcinoma (Figs 35.6 and 35.7)

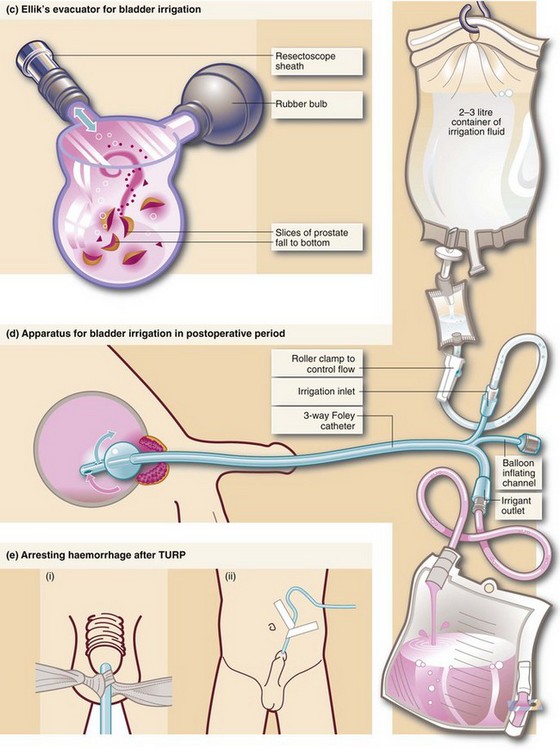

Fig. 35.7 Carcinoma of the prostate

(a) CT scan showing a large carcinoma of the prostate P invading extensively into the bladder anteriorly and posteriorly towards the rectum. This was a late and aggressive form of the disease and the patient lived less than 1 year. (b) and (c) Ultrasound guided biopsy. (b) Transrectal ultrasound scan of prostate showing a small cancer C within the peripheral zone and an acoustic shadow beyond it. The larger central zone is enlarged by benign hypertrophy. (c) After transrectal biopsy. The white line represents bubbles of air left after successful needle biopsy of the tumour

If a patient has skeletal pain, X-rays and radionuclide bone scans are indicated. On X-ray, prostatic bony metastases are typically sclerotic or osteoblastic (i.e. dense, appearing white on X-rays) rather than lytic (as in most other bony secondaries), giving the characteristic patchy ‘cotton-wool’ appearance shown in Figure 35.6. Some lesions, however, are radiolucent. An isotope bone scan can reveal metastases even when a plain X-ray is normal.

Management of prostatic carcinoma

Hormonal therapy

• LHRH agonists (LHRHa) such as goserelin. These drugs need to be injected at 4–12 weekly intervals. Therapy causes initial stimulation of luteinising hormone (LH) release from the pituitary, which in turn causes increased testicular testosterone secretion for up to 2 weeks. This is followed by inhibition of LH release by competitively blocking the receptors, resulting in an ‘anorchic’ state. Hot flushes and sexual dysfunction are the major side-effects. Many patients experience a ‘flare’ of symptoms in the first 2 weeks, aggravating bone pain or spinal cord compression. For this reason, the first 2–3 weeks are usually covered by anti-androgen therapy (e.g. cyproterone acetate or flutamide)

• Removal of both testes by subcapsular orchidectomy. This is a quick and simple scrotal operation and removes about 95% of testosterone synthesised (the rest is from the adrenals), producing an immediate fall in plasma testosterone. The testicular capsules are left in situ and these fill with blood clot and preserve the scrotal contour. There are few side-effects other than hot flushes and sexual dysfunction, and no serious long-term sequelae

• Anti-androgen drugs such as cyproterone acetate or flutamide. These block the binding of dihydrotestosterone to its receptor at cellular level and, in contrast to LHRH agonists, block both testicular and adrenal testosterone. Flutamide may preserve the potential for sexual arousal for longer and may be the preferred treatment for younger patients with advanced disease

Almost inevitably, prostatic cancer eventually escapes its androgen dependency and becomes refractory to hormonal treatment. The mechanism is unknown but occurs at a mean of 2 years after commencing treatment in M+ and 5 years in N+ M0 disease. When this occurs, secondary or salvage treatment with diethylstilbestrol may be of value. This is a synthetic androgen and suppresses LHRH secretion from the hypothalamus, but has a high rate of serious thromboembolic side-effects. Bone metastases can sometimes be palliated by intravenous radioactive strontium. Non-hormone chemotherapy has little to offer, and often only symptomatic and general palliative measures can be offered. The principles and techniques of palliative care are described in Chapter 13. The management of prostatic carcinoma is summarised in Box 35.4.