Disorders of the oesophagus

Carcinoma of the oesophagus

Epidemiology and aetiology

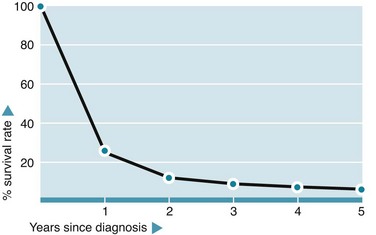

The incidence of oesophageal cancer in Western countries is relatively low compared with cancer of the colon or stomach. It accounts for about 5% of all deaths from cancer, with men at two-fold greater risk than women. The disease is usually advanced by the time of presentation, hence the mortality rate is appalling, with 70% dying within a year and only 8% surviving 5 years (see Fig. 22.1).

Investigation of suspected oesophageal carcinoma

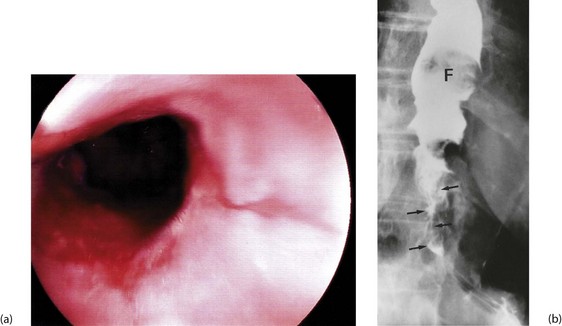

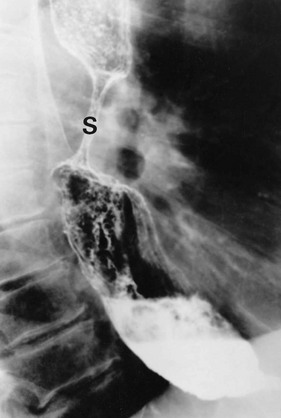

Dysphagia or pain on swallowing (odynophagia) in a middle-aged or elderly patient demands urgent investigation to exclude carcinoma (see Box 22.1). General physical examination is usually unrewarding except in advanced disease. In these cases, there may be signs of wasting, hepatomegaly due to metastases, a Virchow’s node in the left supraclavicular fossa or sometimes hoarseness from recurrent laryngeal nerve involvement. Gastroscopy allows direct inspection of the oesophagus using a flexible endoscope and biopsies are taken of any suspicious areas (Fig. 22.2).

Management of carcinoma of the oesophagus

Surgery

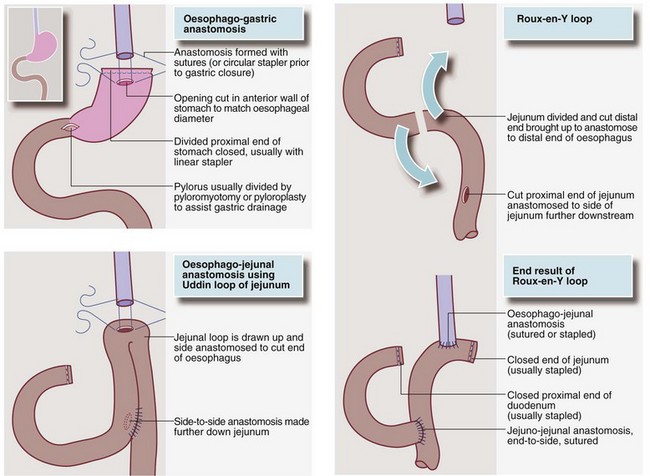

If the tumour arises lower in the oesophagus, a two-stage Ivor Lewis operation is usually performed. The abdomen is opened first, and the stomach mobilised and fashioned into a conduit. The patient is then turned into a left lateral position and the right chest opened, the oesophagus mobilised and the tumour and lymph nodes excised. Finally the gastric conduit is drawn up into the chest and anastomosed to the proximal oesophageal remnant. If this is impossible, a loop of jejunum or a single end of jejunum (Roux-en-Y) is drawn up to make the connection (see Fig. 22.3). Controversy exists about whether extending lymphadenectomy into the neck, so-called ‘three-field lymphadenectomy’, is beneficial. The procedure increases operative risks and only appears to benefit a subgroup with proximal tumours and fewer than five involved nodes.

Inoperable lesions

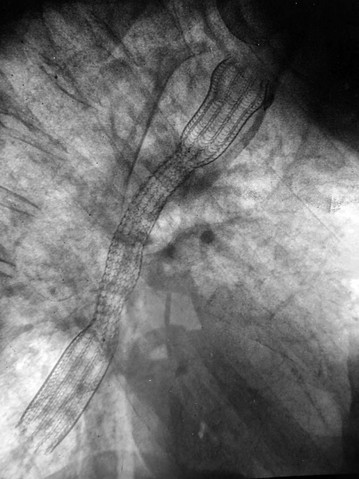

If operation is inappropriate, oesophageal patency can often be restored by palliative ablation of the tumour with laser therapy or argon plasma coagulation via a gastroscope. These treatments can be repeated as the tumour regrows. Alternatively, the oesophagus can be intubated with an expanding metal stent (see Fig. 22.4) through the lesion. This is usually done under intravenous sedation, using the endoscopic technique of pulsion intubation. First the oesophageal lesion is dilated then the stent inserted using X-ray guidance. These tubes relieve symptoms, but food has to be liquidised and the tube kept ‘clean’ by taking fizzy drinks after eating. Patients are more susceptible to acid reflux, for which antacid medication may need to be prescribed. Chemotherapy, external beam radiotherapy and intraluminal brachytherapy (local radiotherapy) are increasingly used for palliation.

Hiatus hernia and reflux oesophagitis

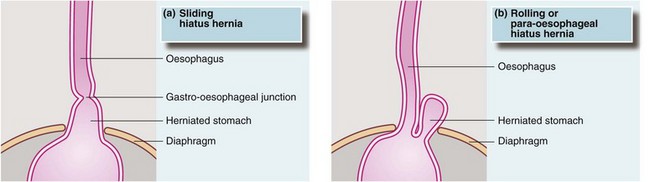

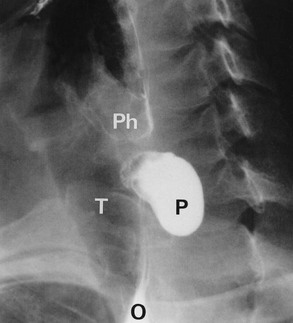

Hiatus hernia occurs when the proximal part of the stomach passes through the diaphragmatic hiatus up into the chest (see Fig. 22.5). Around 90% of hiatus hernias are of the sliding type, in which the gastro-oesophageal junction is drawn up into the chest and a segment of stomach becomes constricted at the diaphragmatic hiatus. The hernia tends to slide up into the chest with each peristaltic contraction. These hernias may become huge and, rarely, may contain the whole stomach including pylorus and first part of the duodenum, sometimes with part of the colon as well. In the 10% of non-sliding cases, the gastro-oesophageal junction remains below the diaphragm and a bulge of stomach herniates through the hiatus beside the oesophagus. These are described as para-oesophageal or rolling hiatus hernias.

Clinical features of reflux oesophagitis

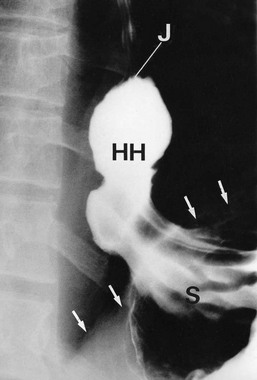

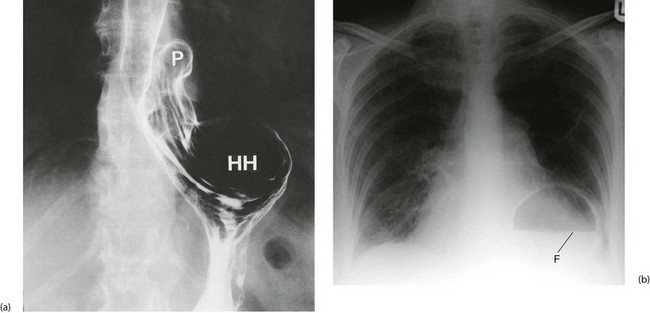

In general, hiatus hernias are assessed at endoscopy, with biopsy if necessary. The latter is important to exclude carcinoma, especially in dysphagia. In specialised units, oesophageal manometry studies can assess the oesophageal muscular function and oesophageal pH studies assess the extent and severity of reflux. These studies help determine which patients are likely to benefit from surgery. Rarely barium swallow examination (see Figs 22.6 and 22.7) may be necessary to delineate complicated anatomy.

Achalasia

Pathophysiology and clinical presentation

Clinically, the cardiac sphincter becomes constricted and the proximal oesophagus dilates with accumulated fluid and solids. Difficulty in swallowing is the usual presenting symptom, together with halitosis, weight loss, reflux of food into the back of the throat. Solids tend to sink to the lower end of the dilated oesophagus, whereas fluids spill over into the trachea causing spluttering dysphagia (see Ch. 18, p. 249) and coughing, particularly at night. Vomiting and retrosternal pain may occur in more severe cases.

Investigation of suspected achalasia

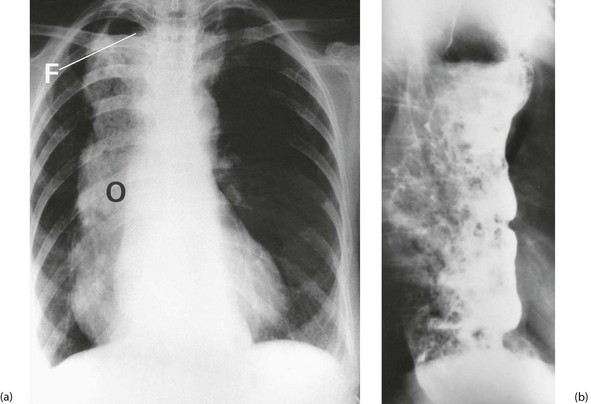

Chest X-ray may show the mediastinal shadow is widened by a dilated oesophagus; sometimes a fluid level in the oesophagus is visible behind the heart Fig. 22.7(b). At endoscopy the typical appearance is of a capacious distal oesophagus, usually with food and fluid residue, and a tight lower oesophageal sphincter that may or may not admit the tip of the gastroscope. It is important to see the oesophago-gastric junction to exclude an occult neoplasm masquerading as achalasia (pseudoachalasia). Barium swallow examination reveals gross dilatation of the oesophagus with a tapering constriction (often described as a ‘bird’s beak’ or ‘rat’s tail’) at the lower end. The constriction barely allows contrast to enter the stomach (see Fig. 22.8). Under fluoroscopic screening, uncoordinated purposeless peristaltic waves can often be seen; these are described as tertiary contractions, distinct from normal coordinated primary and secondary contractions. Oesophageal manometry is the cardinal test for achalasia, demonstrating excessive lower oesophageal sphincter pressure that fails to relax on swallowing, and abnormal peristalsis in patients with a more chronic history.

Management of achalasia

The condition is by its nature incurable, and treatment aims to relieve the distal obstruction. The standard operation is a laparoscopic abdominal procedure involving a longitudinal incision of the lower oesophageal and upper gastric muscle wall until the mucosa bulges through (Heller’s cardiomyotomy); this is best combined with a partial fundoplication to overcome the almost inevitable reflux it will cause. Balloon dilatation is sometimes used as an alternative but often needs to be repeated. Botulinum toxin (Botox) is now often used to relax the lower oesophageal sphincter and is an excellent temporising measure, but needs to be repeated after 3–6 months as the effect wears off. Patients with achalasia should be followed up and periodically endoscoped to exclude developing squamous carcinoma (see Fig. 22.9).

Pharyngeal pouch

Pharyngeal pouch is a rare cause of dysphagia. It arises at the junction of pharynx and oesophagus, and probably results from lack of coordination between the inferior constrictor muscle and cricopharyngeus during swallowing. At this point, there is an area of relative weakness known as Killian’s dehiscence. The result is a progressive mucosal outpouching between the two muscles. The condition is best diagnosed by barium swallow (see Fig. 22.10). Pharyngeal pouch is easily perforated during endoscopy, and therefore in endoscopy to investigate ‘high’ dysphagia, the procedure should be performed by an experienced endoscopist. Treatment of pharyngeal pouch is by surgical excision from the side of the neck, or via a completely endoluminal approach using a stapler to join the pouch to the oesophagus.

Gastro-oesophageal varices

As resistance to flow and pressure rises in the portal venous system, abnormal communications develop between the peripheral portal system and the systemic venous circulation. This is known as portal-systemic shunting. Multiple large veins appear in the peritoneal cavity and retroperitoneal area, making any form of abdominal surgery hazardous. Large submucosal veins also appear at the lower end of the oesophagus and gastric fundus, and are known as gastro-oesophageal varices (see Fig. 22.11). These varices can cause massive gastrointestinal haemorrhage, possibly related to rises in intravariceal pressure. Up to 40% of cirrhotic patients suffer variceal haemorrhage at some stage.

Management of bleeding gastro-oesophageal varices

Treatment

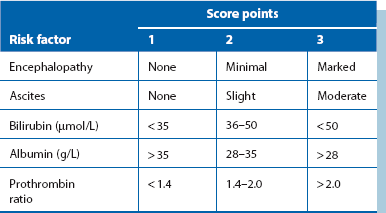

As a last resort, emergency surgical treatment is performed, but all operations carry high mortality in such seriously ill patients. The simplest operation is transgastric oesophageal stapling. A circular stapler is passed into the oesophagus via a gastrotomy, a ligature tied around the oesophagus between the staple cartridge and the anvil, and the gun fired. This places two rows of staples through the full thickness of the oesophageal wall, disconnecting the longitudinal veins. Operative risk in these patients has been calculated using Child’s criteria, shown in Table 22.1.