Disorders of the mouth

Disorders of the oral cavity (excluding salivary calculi)

The main oral disorders are dental caries (tooth decay) and its sequelae, inflammations of the gums and supporting bone (periodontal disease), tumours and premalignant conditions of mucosa (leukoplakia and squamous carcinoma) and disorders of the accessory salivary glands such as retention cysts. The main symptoms and signs are summarised in Box 48.1. Salivary gland disorders are covered in Chapter 47.

Dental caries

Pathophysiology and clinical features

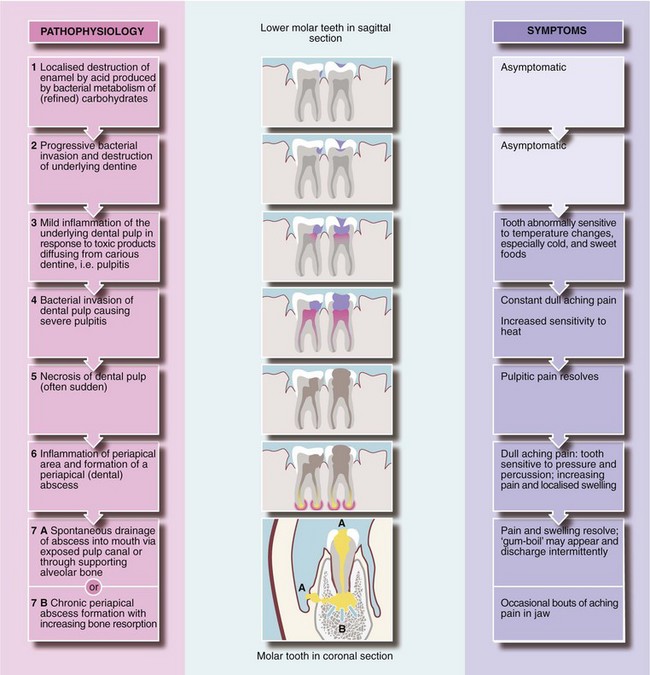

Once enamel is breached, proteolytic bacteria enter the less calcified dentine beneath and cause progressive destruction. The enamel remains intact until the dentine is undermined and the enamel fractures. Thus, dental caries may be well advanced but invisible, even to a dental mirror and probe, and detectable only on X-ray. The decay process is asymptomatic until close enough to the dental pulp to cause inflammation and pain and, eventually, bacterial invasion and abscess formation. The pathological process and corresponding symptoms are outlined in Figure 48.1.

Management of dental caries

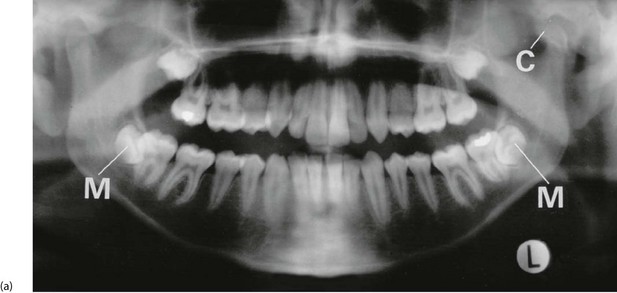

Provided the dental pulp has not been invaded by infection (i.e. become ‘exposed’), a dentist can usually drill out the carious enamel and dentine and restore it (Fig. 48.2) with synthetic resin, silver amalgam or gold, with a sedative insulating lining. Once exposed, the necrotic tissue must be removed by endodontic treatment, and the pulp cavity filled; this is ‘root filling’ (Fig. 48.2). In this way, the tooth can often be preserved.

Fig. 48.2 Dental restorations and root fillings

This oral pantomograph (OPG) film shows silver amalgam restorations for caries in posterior teeth (shown as white radiopacities) and synthetic resin restorations in front teeth (relative radiolucencies in the upper incisors). In addition, the upper left first molar and the lower right first molar (arrowed) have radiopaque root canal fillings, necessitated by dental caries invading the pulp

Tooth extraction and post-extraction problems

Bleeding tooth socket after extraction

Oozing or minor bleeding is easily controlled by the patient biting on a small dry pack such as a folded gauze swab and maintaining pressure for 10–15 minutes. Persistent bleeding can usually be controlled by inserting sutures through the gingival margins across the socket (Fig. 48.3) then biting on a dry gauze pad. Suturing requires local anaesthesia infiltrated into the gingiva on each side of the socket. Absorbable polyglactin sutures are preferred as they do not leave irritating sharp ends and dissolve in 5–10 days. If bleeding continues after these simple measures, the patient should be investigated for a coagulation or platelet abnormality.

Inflammation of the periodontal tissues

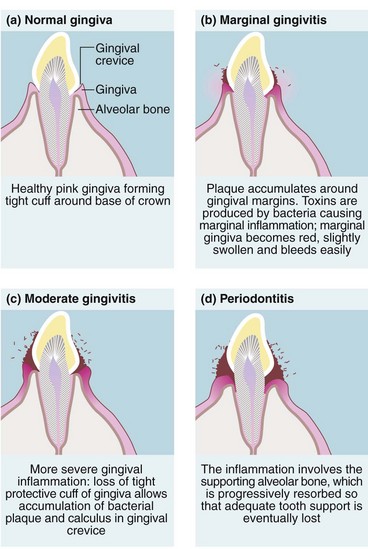

If oral hygiene is inadequate, commensal bacteria colonise the gingival margin and form a white gelatinous plaque (Fig. 48.4). If allowed to persist, plaque becomes adherent to the tooth and becomes mineralised. This is known as calculus, and cannot be removed by tooth brushing. Bacterial toxins then cause gingival inflammation or marginal gingivitis. This appears as swelling and redness of the gums and bleeding during tooth brushing.

Figure 48.5 shows gingivitis causes eversion of the gingival margin. This encourages more plaque and calculus to form and results in greater gum trauma from food, both leading to more inflammation. If untreated, inflammation extends to deeper tissues causing progressive resorption of alveolar bone and destruction of periodontal membrane, known as periodontitis. By this stage, the gingiva is thickened and inflamed with a purulent discharge. This explains the old term ‘pyorrhoea’ or flowing of pus. Despite this, the patient is remarkably pain free, although halitosis is obvious.

Fig. 48.5 Gingivitis and periodontitis

(a) Normal healthy gingivae. (b) Chronic gingivitis showing accumulated plaque and calculus around the gingival margins. At this stage, no alveolar bone has been destroyed and the inflammatory process is potentially reversible. Many of these teeth had to be extracted, however, because of rampant caries

Sometimes an acute periodontal abscess may complicate periodontitis.

Management of gingivitis and periodontitis: Gingivitis and periodontitis is preventable by thorough and regular tooth brushing and use of dental floss, plus periodic dental scaling to remove inaccessible plaque and calculus. Initial scaling and careful oral hygiene instruction and supervision cures gingivitis, which is reversible. During the early stages of improved oral hygiene, bleeding increases through brushing inflamed tissues but soon subsides unless further periodontal treatment is needed.

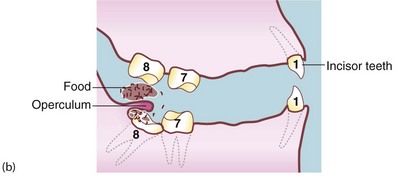

Pericoronitis

This occurs when a lower third molar (wisdom tooth) is impacted against the second molar or the ramus of the mandible so that its eruption is prevented (see Fig. 48.6). If a flap (operculum) of gingiva partly overlies the impacted tooth, this creates a space around the buried tooth crown (Fig. 48.6b). Food and bacterial plaque collect and cause acute infection, which may extend outwards, even into the parapharyngeal area.

Management of pericoronitis: Pericoronitis is cellulitis with incipient abscess formation caused by mixed organisms usually sensitive to penicillin or metronidazole. It is treated by irrigating beneath the flap with hydrogen peroxide and mouth washes several times daily with warm salty water. Rapid relief is obtained by removing the upper wisdom tooth if it impinges on the flap. Oral phenoxymethylpenicillin (penicillin V) and metronidazole are given if the patient is systemically unwell. If attacks are recurrent, the lower wisdom tooth may be removed surgically.

Acute ulcerative gingivitis (vincent’s infection)

Management of acute ulcerative gingivitis: Vincent’s infection rapidly responds to metronidazole tablets (200 mg t.d.s.), usually with full recovery of gingival morphology; penicillin is also effective. Tooth brushing is painful during an attack and the mouth should be frequently rinsed with warm water or weak hydrogen peroxide to keep it clean. Afterwards, careful attention to oral hygiene usually prevents recurrence.

Tumours of the oral mucosa

Clinical features of oral cancer

Oral cancer usually presents as a slowly enlarging chronic indurated ulcer which fails to heal (Fig. 48.7b and c). An early lesion may present as a mucosal swelling. Lesions are usually painless unless secondarily infected, although advanced lesions may cause pain as they invade deeply. Carcinoma of the tongue, for example, may cause pain referred to the ear or pharynx via the lingual nerve or chorda tympani.

Fig. 48.7 Premalignant and malignant conditions of the mouth

(a) Leukoplakia under tongue. (b) Ulcerating squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the cheek. (c) Ulcerating SCC of the tongue. (d) Squamous cell carcinoma of the lip. This man of 60 had smoked a pipe most of his life. He tended to keep the pipe constantly in his mouth while he worked. He presented with a non-healing ulcer of the lip, proven to be a well-differentiated SCC on biopsy. A wedge resection of the lip was performed and produced a cure

Leukoplakia

Leukoplakia means ‘white plaque’, and describes white patches on oral mucosa which cannot readily be scraped off (see Fig. 48.7a). This distinguishes them from candidal infections. White plaques may be caused by friction, oral lichen planus or more rarely lupus erythematosus, but the main importance of leukoplakia is that it may represent epithelial dysplasia or even carcinoma-in-situ.

Epulis

A fibrous epulis is simply a benign fibrous tissue tumour arising from periodontal membrane or nearby periosteum. It forms a smooth, firm, slowly growing lump, covered with normal gingiva. A fibrous epulis usually emerges between two teeth, which may be pushed apart by pressure. Treatment is by excision with curettage of the origin to prevent recurrence (Fig. 48.8).

A giant cell epulis arises in a similar location but grows much faster. It forms an irregular red fleshy mass which ulcerates and bleeds. The lesion consists of numerous giant cells in a vascular stroma, which may invade local bone. Treatment involves extracting associated teeth and excising and curetting bone to avoid recurrence (Fig. 48.8).

Pyogenic granulomas may occur on gums or oral mucosa of the lips. They look like pyogenic granulomas of skin and often occur in pregnancy (see Ch. 46, p. 574).

Miscellaneous disorders causing intraoral swelling

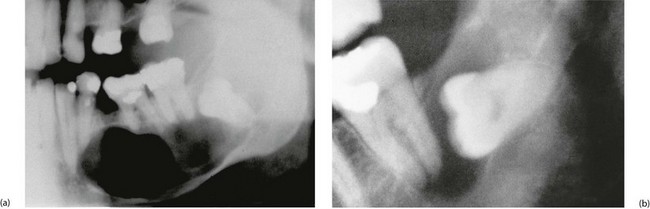

Cysts and tumours of the jaws

Various cystic lesions and tumours arise in the jaws. Many are abnormalities of tooth-forming epithelium, developmental or acquired. Figure 48.9b shows a mandibular dentigerous cyst, a developmental cyst. They are rare and can usually be diagnosed radiologically. The jaws are occasionally the site of benign or malignant bone tumours such as osteosarcoma and osteoclastomas. They can also be affected by metastatic tumours from breast or prostate. Bony growth disorders such as fibrous dysplasia and Paget’s disease may also affect the jaw.

Fig. 48.9 Dental cyst and dentigerous cyst

(a) Large dental cyst in the mandible. This arose from tooth-forming epithelial remnants in the apical area of the lower left second premolar tooth which was extracted several months beforehand due to chronic periapical infection. (b) Dentigerous cyst associated with the crown of an unerupted lower third molar. These cysts originate from epithelial remnants of the tooth bud