Disorders of the motor neurone

The motor neurone, or anterior horn cell, lies in the anterior horn of the spinal cord. Its axon extends to the muscle and is the final common pathway for motor output. Disorders of the motor neurone are uncommon.

Motor neurone disease

Clinical features

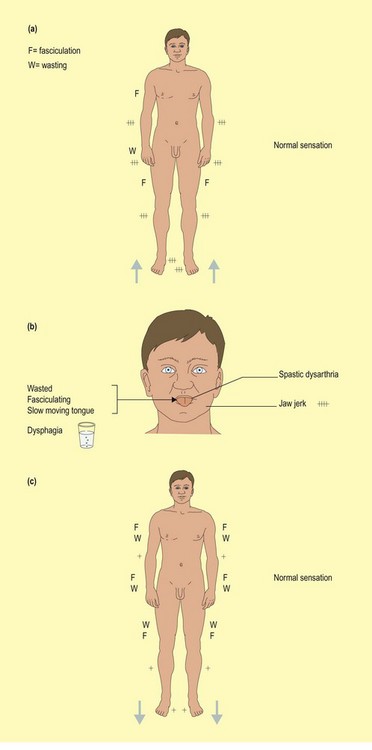

There are three main patterns of disease (Fig. 1). All are progressive and evolve at different rates. They overlap significantly and in the late stages tend to merge into a diffuse, combined upper motor neurone (UMN) and lower motor neurone (LMN) disorder. The differential diagnosis depends on the pattern of presentation. Sensation must be normal to make the diagnosis. The overall prognosis is poor; death is usually due to respiratory complications from bulbar or respiratory muscle weakness.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

This commonly presents with stiffness and weakness of the hands, muscle cramps and discomfort. In some cases, onset may be proximal, resembling a plexopathy or with foot drop, simulating peroneal nerve palsy. Over the following months, more widespread, patchy weakness appears that may affect any muscle, except the extraocular muscles. Weakness becomes more diffuse and spreads to the truncal and bulbar muscles. The hands appear severely wasted and there are often fasciculations in the interossei and sometimes other muscle groups. It may be necessary to observe the patient’s trunk and limb muscles for 30 s or more in order to see the fasciculations. Tone is usually normal and weakness is initially patchy. Despite wasting, reflexes are brisk and plantar responses usually become extensor during the disease. The most common differential diagnosis is cervical myeloradiculopathy, sometimes with additional lumbar radiculopathy.

Inherited diseases of upper and lower motor neurones

Spinal muscular atrophies. These present with pure LMN disorders. Inheritance is variable and there are three forms: rapidly fatal infantile (Werdnig–Hoffman syndrome), and slowly progressive juvenile (Kugelberg–Welander syndrome) or adult onsets. They are allelic variants of the same gene.

Spinal muscular atrophies. These present with pure LMN disorders. Inheritance is variable and there are three forms: rapidly fatal infantile (Werdnig–Hoffman syndrome), and slowly progressive juvenile (Kugelberg–Welander syndrome) or adult onsets. They are allelic variants of the same gene. Hereditary spastic paraparesis (usually autosomal dominant). This presents with spasticity of the legs. The arms are stronger, often with compensatory hypertrophy.

Hereditary spastic paraparesis (usually autosomal dominant). This presents with spasticity of the legs. The arms are stronger, often with compensatory hypertrophy. Adrenoleucodystrophy (X-linked recessive). This presents with mixed UMN and LMN disease and mild adrenal insufficiency.

Adrenoleucodystrophy (X-linked recessive). This presents with mixed UMN and LMN disease and mild adrenal insufficiency. X-linked bulbospinal neuronopathy. This presents with bulbar palsy, pronounced action-induced fasciculations, diabetes, gynaecomastia, infertility and mild neuropathy. It is due to a defect of the androgen receptor and has a much better prognosis than MND.

X-linked bulbospinal neuronopathy. This presents with bulbar palsy, pronounced action-induced fasciculations, diabetes, gynaecomastia, infertility and mild neuropathy. It is due to a defect of the androgen receptor and has a much better prognosis than MND.