Disorders of the male genitalia

Disorders of the scrotal contents

Introduction

Abnormalities of the scrotal contents include disorders of the testis or its coverings, the spermatic cord and inguino-scrotal hernias (see Ch. 32). Distinguishing between them usually requires only clinical examination. Diagnoses that must not be missed are testicular tumours and testicular torsion. Other problems include inflammation, hydrocoeles and cysts, maldescent and testicular trauma, as well as varicocoele. Male sterilisation and disorders of the penis are also covered in this chapter.

Clinical examination of scrotal lumps and swellings

A lump or swelling in the scrotum may be:

• A solid or cystic mass arising from a component of scrotal contents or spermatic cord. These include testis, epididymis, epididymal appendage, vas deferens and pampiniform venous plexus

• A collection of fluid in the tunica or processus vaginalis (hydrocoele)

• An indirect inguinal hernia extending along the embryological path of testicular descent into the scrotum

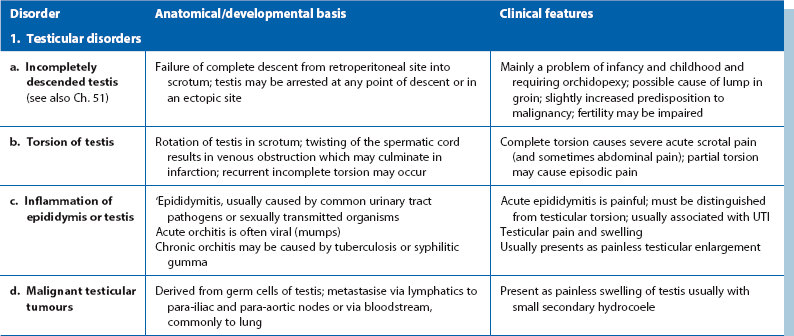

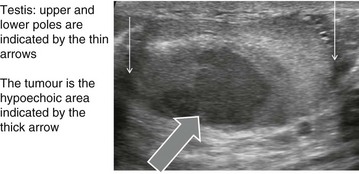

The important disorders of the scrotum and contents are summarised in Table 33.1, with their anatomical and clinical significance.

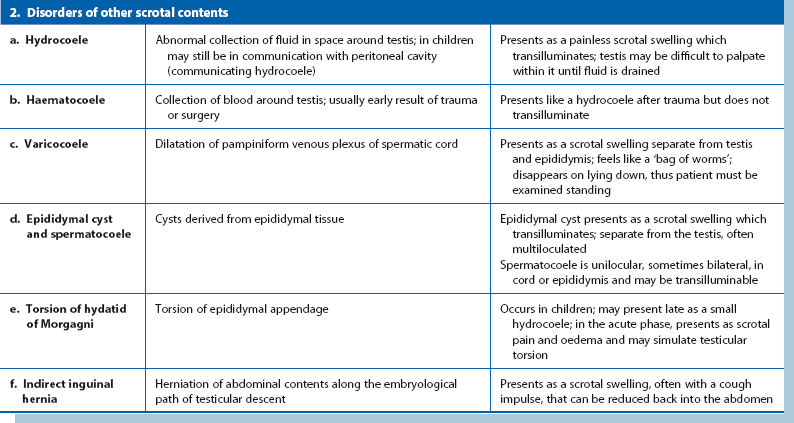

The origin of a scrotal lump: The first objective is to determine if the swelling arises in the groin, the spermatic cord or the scrotum and is achieved by palpating the cord at the scrotal neck. In a hernia, the cord is broader than normal and the hernia can be shown to communicate with the abdominal cavity by a cough impulse or by reducing the hernia. Spermatic cord swellings (varicocoele or cyst) are usually easily recognised. In purely scrotal lumps, the spermatic cord is a normal diameter.

Testicular and epididymal lumps: With a scrotal abnormality, an attempt should be made to palpate testis and epididymis separately, and to determine their relationship to the lump. If the testis is enlarged or has a lump within it, this is a tumour until proven otherwise. Testicular swellings due to lymphoma, leukaemia or granulomatous infections (e.g. tuberculosis or syphilitic gumma) may be softer but this is unreliable. Any testicular pathology may cause a little fluid to accumulate in the tunica vaginalis producing a small secondary hydrocoele but this rarely interferes with testicular palpation.

Lumps in the epididymis (cysts, chronic epididymitis or, rarely, tuberculous granulomata) are discrete from, but attached to, an otherwise normal testis. Tiny focal lumps in the epididymis are rarely clinically important. Infective lesions cause diffuse and usually painful thickening of the epididymis, whereas epididymal cysts are almost always located at the upper pole. Epididymal cysts are filled with clear fluid and therefore transilluminate. Transillumination (Fig. 33.1) is demonstrated by shining a strong beam of light through the scrotum in a partly darkened room. If the lesion is fluid-filled, it will glow (except in the case of blood). About 10% of cysts in the epididymis, and most in the cord, are filled with an opalescent fluid containing spermatozoa (spermatocoeles) which can also transilluminate.

Inflammation of the epididymis and testis

In epididymitis, pain usually begins acutely. It may present as a surgical emergency and be clinically indistinguishable from testicular torsion. On examination, the affected side of the scrotum and its contents are swollen, oedematous and tender, and the scrotal skin can be red and warm. It may be difficult to palpate testis and epididymis separately once infection is established. In a boy under 15, epididymitis must never be diagnosed in the absence of urinary symptoms, a proven urinary infection or urethritis. Such an ‘acute scrotum’ must be explored to exclude torsion (see p. 428).

Tuberculous epididymitis: Tuberculosis may involve the epididymis via bloodstream spread from a pulmonary or other focus. A tuberculous urinary tract infection can spread to the epididymis, with swelling as the presenting complaint. Typically, the whole length of the epididymis is thickened, non-tender and ‘cold’. In contrast to bacterial epididymitis, the epididymis can be readily distinguished from the testis on palpation. If untreated, the testis may also become involved.

Diagnosis requires analysis of serial early morning urine specimens (EMUs) for mycobacteria or, more reliably, histological examination of percutaneous needle biopsies. If tuberculosis is confirmed, a search must be made for pulmonary and urinary tract disease (see Ch. 38).

Hydrocoele

A hydrocoele is an excessive collection of fluid within the tunica vaginalis, i.e. in the serous space surrounding the testis. Like the peritoneal cavity, the tunica normally contains a little serous fluid which is produced and reabsorbed at the same rate (Fig. 33.2).

Management: For symptomatic patients, a hydrocoele operation can be performed by everting the sac and oversewing the edges (Jaboulay procedure) or plicating the sac (Lord’s method). If the sac is thick, it is best excised. Alternatives include observation alone or periodic aspiration (rarely performed) if the patient is unsuitable for surgery. If a testicular tumour is a possibility, a hydrocoele must not be aspirated as malignant cells can be disseminated via scrotal skin to its lymphatic field.

Hydrocoele of the cord

Rarely, a hydrocoele develops in a remnant of the processus vaginalis somewhere along the course of the spermatic cord. This hydrocoele also transilluminates, and is known as an encysted hydrocoele of the cord (see Fig. 33.3). In females, a multicystic hydrocoele of the canal of Nuck sometimes presents as a swelling in the groin. It probably results from cystic degeneration of the round ligament.

Epididymal cyst and spermatocoele

Multiple cysts can develop in the upper pole of the epididymis and present as a painless scrotal swelling (see Fig. 33.3). Epididymal cysts affect a slightly younger age group than hydrocoeles. The testis can be palpated separately from the cysts, which transilluminate.

Varicocoele

A varicocoele (see Figs 33.3 and 33.4) represents dilatation and tortuosity of the pampiniform plexus of the spermatic vein in the cord. The condition is much more common on the left (90%), so it may result from the different venous drainage of the two sides: on the left, the testicular vein drains into the high-pressure renal vein, whereas the right testicular vein drains directly into the inferior vena cava.

Testicular tumours

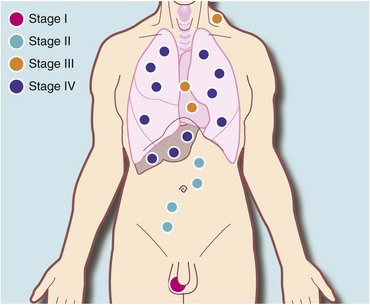

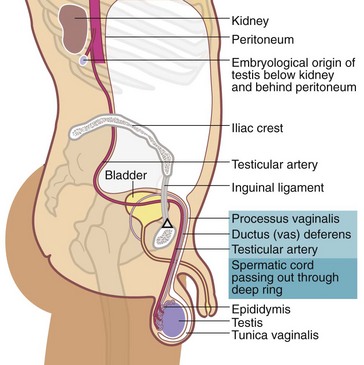

Testicular tumours are relatively uncommon, making up about 1.5% of male cancers, but they are the most common cancer in men in their third and fourth decades. They are important because curative treatment is now available for most of them. Testicular lymphatic drainage and the route of lymphatic metastases is towards intra-abdominal nodes and is determined by the embryology of testicular descent (see Fig. 33.5). Note that this is different from scrotal skin, which drains towards inguinal nodes.

Fig. 33.5 Embryological descent of the testis

The testicular artery marks the line of descent of testis towards the scrotum. In the embryo, the arterial supply is direct from the aorta and this persists even when the testis has reached the scrotum

More than 90% of primary testicular tumours are derived from germ cells, the rest being classified by the World Health Organization as sex cord/gonadal stromal tumours. A detailed classification of malignant testicular tumours is shown in Box 33.2 and the WHO histopathological classification is shown in Box 33.3. Germ cell testicular tumours are generally fast-growing, aggressive tumours that metastasise to intra-abdominal lymph nodes and later via the bloodstream to the lungs.

Pathology of testicular tumours

Seminomas: More than half of malignant testicular tumours are seminomas, derived from spermatocytes (Fig. 33.6). They occur predominantly between the ages of 20 and 45 with a peak incidence at 35 years. The cut surface of a seminoma is typically pale, creamy-white and homogeneous. Histologically, tumour cells are uniform and tightly packed. A distinct but rare form of seminoma, spermatocytic seminoma, occurs between the ages of 50 and 70 years and almost never metastasises.

Teratomas: Teratomas are slightly less common than seminomas and their peak incidence is a decade earlier. Since they are derived from multipotent cells, teratomas may contain tissue from all germ cell layers: ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm. Teratomas exhibit a wide range of differentiation. Differentiated and intermediate tumours contain a collection of tissues resembling mature adult tissues: in particular, squamous epithelium (ectodermal), cartilage and smooth muscle (mesodermal), and respiratory epithelium (endodermal). Consequently, the cut surface often appears variegated, with cystic areas and patches of necrosis and haemorrhage; this is easily distinguished from seminoma with the naked eye.

Investigation and treatment of testicular tumours

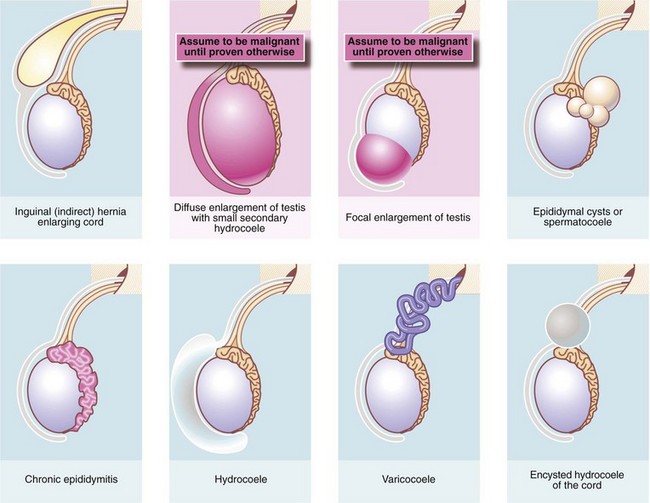

The first investigation is scrotal ultrasonography. If this confirms a solid testicular mass, surgical exploration is required. Preliminary staging investigations are usually performed next, including chest X-ray or CT (to look for hilar node involvement and lung secondaries), CT abdomen and pelvis to assess retroperitoneal nodes and blood levels of tumour markers (which must be measured before treatment). A standard method of staging testicular tumours is shown in Figure 33.7 and Box 33.4. Tumour markers contribute to diagnosis and staging and are useful for tracking residual or recurrent metastases because blood levels correlate with tumour bulk. Serial postoperative measurements help monitor disease progress and the impact of therapy.

Tumour markers: Human chorionic gonadotrophin (beta-hCG) is secreted by syncytiotrophoblastic cells and levels may rise in any tumour type, particularly poorly differentiated germ cell tumours. Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) is produced by yolk sac elements. About 75% of patients with metastatic teratoma have elevated AFP levels but this marker is not expressed in seminoma. Lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) is elevated in more than half the patients with metastatic seminoma.

Surgical exploration: Orchidectomy is the only appropriate treatment for the primary tumour and is usually performed as part of the diagnostic process. The surgical approach is via an inguinal incision to avoid involving scrotal skin. The spermatic cord is temporarily clamped to prevent venous spread of tumour cells and the testis is brought out for inspection and palpation. If the testis is obviously malignant, orchidectomy is performed, dividing the cord at the internal inguinal ring. If there is diagnostic doubt, a testicular biopsy is taken and examined immediately by frozen section before proceeding. The other testis is usually unaffected and can be preserved. Further treatment is planned according to tumour type and stage.

Management of seminoma: For stage 1 seminoma, i.e. disease confined to the testis, some oncologists advise no further treatment after orchidectomy, although carboplatin-based chemotherapy is occasionally recommended. Seminoma is very radiosensitive and radiotherapy can also play a role for the primary, although it is not usually recommended by the European Association of Urologists in view of the high cure rate from standard treatment. For stages IIa and b (i.e. abdominal lymphadenopathy up to 5 cm diameter), radical radiotherapy to the ipsilateral (same side) para-aortic and iliac nodes gives a cure rate of about 95%. Oligospermia of the contralateral testis may occur even if it is lead-shielded but is usually transient. In stage IIb, chemotherapy is an alternative to radiotherapy using etoposide and cisplatin (EP), or cisplatin, eposide, bleomycin (PEB).

Management of teratomas and other non-seminomatous germ cell tumours: Up to 25% of patients with stage I disease would relapse within a year of orchidectomy without further treatment. Radiotherapy has no curative role in these types of tumour. There are three options for further treatment for stage I disease:

In the USA, lymph node dissection is often employed and provides a good cure rate but risks ejaculatory failure from autonomic nerve damage. In the UK, meticulous surveillance is the preferred option. Chemotherapy for relapse is virtually always successful and thus the 75% of patients that do not relapse are spared additional treatment.

Long-term surveillance: After chemotherapy, surgical debulking (‘salvage’) of residual lymph node masses is occasionally indicated. In the long term, tumour markers and sequential CT scans are used to monitor the success of treatment. Recurrent disease can nearly always be successfully treated by radiotherapy, chemotherapy or surgery.

Fertility: Many patients with testicular tumours are already subfertile at presentation, and chemotherapy is likely to further adversely affect fertility. Patients need to be counselled carefully and, if required, semen can be collected and stored before treatment so that artificial insemination or in vitro fertilisation may be performed later. However, the success rate is poor.

Absent scrotal testis (cryptorchidism)

• Retractile—intermittent active cremasteric reflex draws the testis out of scrotum. It can be gently ‘milked’ back into the scrotum

• Incomplete descent—testis lies along the normal line of descent; intra-abdominal, inguinal or pre-scrotal (Fig. 33.5)

• Ectopic—abnormal line of testicular descent outside the external ring; testis may be palpable in the perineum, femoral region or base of penis

• Atrophic—secondary to trauma, iatrogenic (hernia operation or scrotal surgery) or androgen deprivation as part of prostate cancer treatment. Occasionally, an adult testis may become displaced upwards towards the inguinal canal following trauma or hernia surgery; this is known as a trapped testis. The testis is normal sized but is fixed in position by adhesions. If trauma was the cause and there were other major injuries, the scrotal injury may have been overlooked

• Absent—antenatal intra-abdominal torsion, orchidectomy after delayed diagnosis of torsion or bilateral orchidectomy for treatment of prostate cancer

Management of maldescent of the testis

In developed countries, maldescent is usually identified at screening during early childhood and surgically corrected by orchidopexy at a young age (see Ch. 51); to best preserve spermatogenesis, the testis should be surgically placed in the scrotum between 6 months and 1 year. There is some evidence that orchidopexy before the age of 10 decreases the risk of testicular cancer.

Torsion of the testis or epididymal appendage

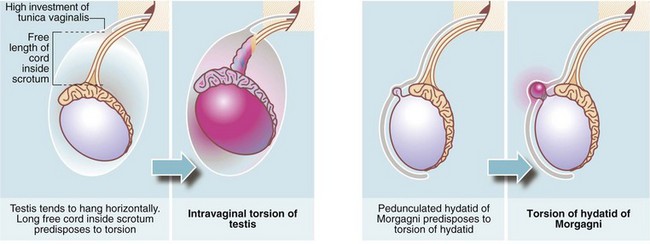

Testicular torsion (Figs. 33.8 and 33.9)

In infants, the newly descended testis and its investing tunica vaginalis are mobile within the scrotum. These testes may undergo extravaginal torsion which presents as a hard, swollen testis. Later in childhood, the testis becomes suspended in a near vertical position, anchored by the spermatic cord and by attachments to the posterior scrotal wall. This attachment prevents rotation. Minor anatomical variations can produce a narrow-based pedicle with a horizontal (‘bell-clapper’) testicular lie, that allows the testis to twist about its axis within the tunica (intravaginal torsion). When this occurs, pampiniform plexus veins become compressed causing venous congestion. After a few hours, venous infarction occurs unless torsion is corrected. Trauma during sport may sometimes initiate the process, and there have been reports of successful manual untwisting on the sports field. In general, however, torsion is an emergency requiring prompt diagnosis and urgent surgical treatment to save the testis.

Torsion of the epididymal appendage (hydatid of morgagni)

The hydatid of Morgagni is a small embryological remnant at the upper pole of the testis (see Fig. 33.9). This may undergo torsion and produce symptoms similar to testicular torsion, out of proportion to the small size of the infarcted tissue. Infarction of the hydatid is of no consequence except that it must be distinguished from testicular torsion.

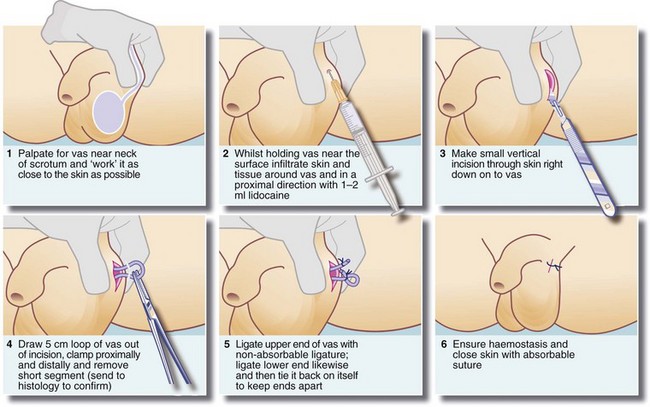

Male sterilisation

Male sterilisation by vasectomy is a simple, effective method of birth control. It can be performed under local anaesthesia at little cost and requires no special equipment. The essential prerequisite is that the couple involved should have completed their family, since reversal is technically difficult and unreliable. A technique of vasectomy is illustrated in Figure 33.10.

Disorders of the penis

Problems with the foreskin (prepuce) are common and form most penile surgical disorders. Other disorders are uncommon in adults but the most serious is carcinoma of the penis. In children, penile disorders are either developmental or minor inflammatory conditions, discussed in Chapter 51. Disorders of the foreskin include balano-posthitis (inflammation of the glans and foreskin), phimosis (stricture of the preputial meatus), paraphimosis (acute constriction of the glans by a tight retracted foreskin) and balanitis xerotica obliterans (idiopathic sclerosis of the foreskin). Peyronie’s disease (idiopathic fibrosis of the corpora cavernosa) is now a frequent presentation in urological clinics (see below). Exclusion of cancer is usually the first step.

Foreskin problems in adults

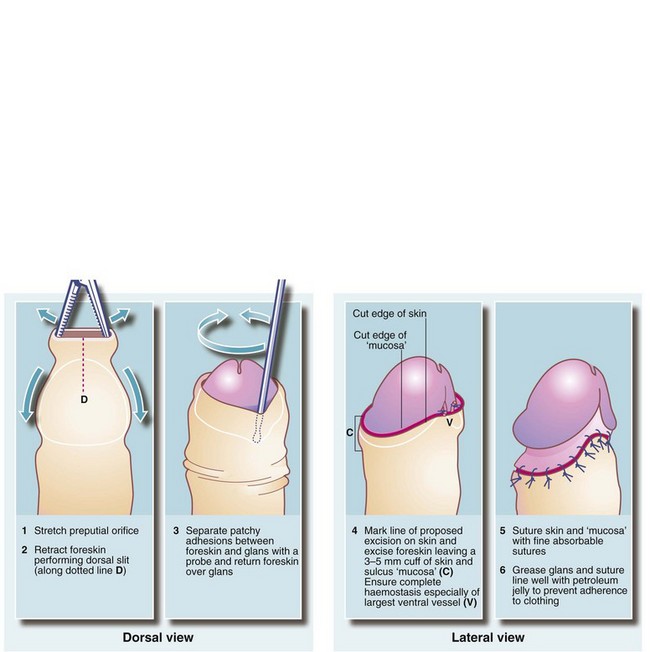

Circumcision

Circumcision should be reserved for unresolved phimosis, recurrent balanitis and sclerosis from balanitis xerotica obliterans. A surgical technique is shown in Figure 33.11. During the operation, the urethral meatus should be checked for stenosis. If present, a meatotomy may be required. An occasional early postoperative complication is haemorrhage which usually requires surgical re-exploration. Postoperative bleeding can best be prevented by meticulous haemostasis at operation.

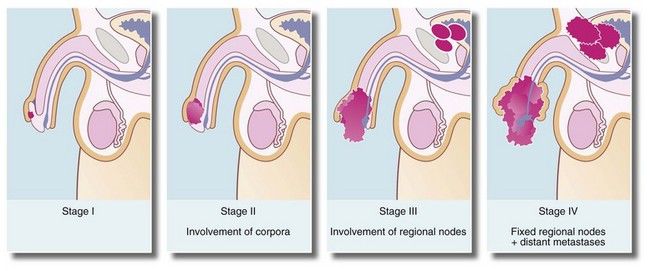

Carcinoma of the penis

Histologically, the tumours are squamous cell carcinomas, usually well differentiated, which arise from the inner surface of the foreskin or the glans penis near the coronal sulcus. The tumour invades locally and tends to penetrate the distal urethra (Fig. 33.12a). Metastatic spread is to inguinal lymph nodes (see Fig. 33.12b). Erythroplasia of Queyrat is the term given to severe dysplasia and carcinoma-in-situ of the glans that may represent a precursor of invasive carcinoma.

Most cases of carcinoma of the penis are found in the elderly. The disease is usually well advanced before an irregular lump, bleeding or discharge is noticed. In uncircumcised males, the lesion may be hidden by the foreskin. Figure 33.13 illustrates staging of the disease.