Disorders of the lower radioulnar joint

Disorders of the inert structures

Pain felt at the wrist during pronation and supination movements of the forearm inculpates the distal radioulnar joint. The source can be the joint capsule,1 the ligaments2–4 or the articular disc.

Capsular pattern

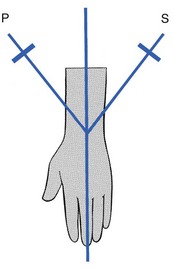

The capsular pattern of the lower radioulnar joint presents with pain at the end of range of the two movements (pronation and supination, Fig. 22.1) and indicates arthritis. Usually there is only pain at end-range but sometimes there may be equal limitation, or slightly more limitation of supination than of pronation.

Arthrosis

When a fracture of the distal part of the radius fails to unite properly, arthrosis at the distal radioulnar joint may follow. Mal-union of the distal part of the ulna does not give rise to persistent problems5 and painless ulnar styloid non-union is a frequent incidental radiographic finding.6

Monoarticular steroid-sensitive arthritis

Arthritis may develop without a provable cause such as rheumatoid or traumatic arthritis. Furthermore, the condition will worsen when attempts are made to mobilize the joint. Such a condition responds particularly well to intra-articular triamcinolone.7

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) involves the wrist in up to 95% of cases. The distal radioulnar joint is affected in 31–75% of these patients and is frequently the first compartment of the wrist involved,8 often bilaterally.9 Triamcinolone suspension injected intra-articularly once or twice a year may keep the joint free from symptoms.10

Long-standing rheumatoid arthritis results in ligamentous laxity. At the distal radioulnar joint this leads to the so-called ‘caput ulnae syndrome’: dorsal subluxation of the distal part of the ulna, supination of the carpus on the forearm, and palmar dislocation of the tendon of the extensor carpi ulnaris.11–14

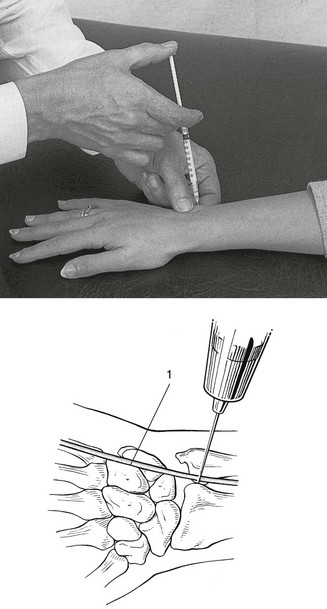

Technique: intra-articular injection![]()

The patient sits at the couch with the arm lying in pronation. A 1 mL syringe filled with triamcinolone acetonide and fitted with a 2 cm needle is used. The joint line, which is very short, is identified just radially to the head of the ulna. Gliding movements between the ulna and radius may help to find it. As the extensor digiti minimi tendon lies just dorsal to the joint line, care must be taken to avoid puncturing it (Fig. 22.2).

Non-capsular pattern

Limited supination

After a mal-united Colles’ fracture, shortening of the radius may be responsible for an irreversible limitation of supination only, with the end-feel of a bony block.15,16 The movement may be painful in recent cases but should become painless in due course.

A dorsal dislocation of the ulna also presents with a block to supination and a visible dorsoulnar prominence. The mechanism for dorsal subluxation and dislocation is extreme pronation and extension, which pull the ulnar head out through the dorsal capsule. Triangular fibrocartilage complex avulsion and attenuation of the palmar radioulnar ligament will allow this dislocation.17

Painful supination

In tenosynovitis of the extensor carpi ulnaris, passive supination may be painful at the end of the range. This is a localizing sign, indicating that the lesion lies in the groove at the base of the ulna. The tenosynovitis will, of course, be diagnosed by interpreting resisted movements at the wrist (see p. 345).

Limited pronation

A block to pronation is present in palmar dislocations of the ulna. On inspection–palpation there will be a volar–ulnar prominence and a palpable radial sigmoid notch.18

Disorders of the triangular fibrocartilage complex

Palmer devised a classification system of TFCC tears in 1989.19 The main division is between traumatic type I and atraumatic (degenerative) type II tears. The traumatic conditions (type I) follow hyperpronation or axial load-and-distraction injury to the ulnar part of the wrist (e.g. fall on an outstretched extremity20) and include perforation and avulsion21 with or without fracture.22 Type IA (Avascular articular disc) tears are the most common. The other type I tears are peripheral in nature: type IB (Base of the styloid) tears; type IC (Carpal detachment) tears; type ID (detachment from the raDius). The degenerative disorders (type II) result from chronic injuries after repetitive loading on the ulnar side of the wrist.23 They vary from triangular fibrocartilage wearing to chondromalacia and ligament perforation.24 Degenerative changes in the TFCC often accompany those in the distal radioulnar joint.25

TFCC disorders result in ulnar-sided wrist pain.26 Uncomplicated cases show a capsular pattern at the radioulnar joint. Complicated cases may present with some subluxation of the joint (limitation of pronation or supination). A provocative test for TFCC lesions, the ulnar grind test, has been described. It involves dorsiflexion of the wrist, axial load, and ulnar deviation or rotation. If this manœuvre reproduces the patient’s pain, a TFCC tear should be suspected.27 Another quick and highly sensitive test to evaluate tears of the TFCC is the ‘press test’, which axially loads the wrist in ulnar deviation as the patient pushes him- or herself up from a seated position.28 The best place to palpate the TFCC is between the tendons of the extensor and flexor carpi ulnaris, distal to the styloid and proximal to the pisiform. In this soft spot of the wrist, there are no other structures than the TFCC.29 Acceptable methods to confirm the clinical diagnosis are magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)30 and high-resolution ultrasonography.31

The treatment depends on type and degree of the lesion. Most symptomatic lesions respond very well to relative rest and one or two intra-articular injections into the distal radioulnar joint. Surgery is the treatment of choice when gross instability occurs. Instability is found when the ligamentous components of the TFCC proper – the dorsal and palmar radioulnar ligaments – are torn.32 Early surgery is then preferred.33,34 Chronic disorders of the TFCC, often combined with instability, require arthroscopic35–37 or open repair,38 including ulnar shortening.39,40 The results are good.41

Disorders of the contractile structures

Resisted pronation and supination are not tested in the standard functional examination, because they are not relevant at this level. However, resisted pronation can be performed as an accessory test in order to examine the pronator quadratus muscle. This being said, a lesion of this structure has never been described and does not seem to exist. Resisted pronation movement also tests the common flexor tendon (in the case of golfer’s elbow) and the pronator teres muscle, but in lesions of these two structures, pain is felt near the elbow (see Ch. 19).

References

1. Kleinman, WB, Graham, TJ, The distal radioulnar joint capsule: clinical anatomy and role in posttraumatic limitation of forearm rotation. J Hand Surg. 1998;23A(4):588–599. ![]()

2. Kihara, H, Short, WH, Werner, FW, et al, The stabilizing mechanism of the distal radioulnar joint during pronation and supination. J Hand Surg. 1995;20A(6):930–936. ![]()

3. Van der Heijden, EP, Hillen, B, A two-dimensional kinematic analysis of the distal radioulnar joint. J Hand Surg. 1996;21B(6):824–829. ![]()

4. Ward, LD, Ambrose, CG, Masson, MV, Levaro, F, The role of the distal radioulnar ligaments, interosseous membrane, and joint capsule in distal radioulnar joint stability. J Hand Surg. 2000;25A(2):341–351. ![]()

5. Cooney, WP, Dobyns, JD, Linscheid, RL, Complications of Colles’ fractures. J Bone Joint Surg 1980; 62A:613. ![]()

6. Burgess, RC, Watson, HK. Hypertrophic ulna styloid non-unions. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1998; 228:215.

7. Cyriax, JH. Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, vol I, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions, 8th ed. London: Baillière Tindall; 1982.

8. De Smet, L, The distal radioulnar joint in rheumatoid arthritis. Acta Orthop Belg. 2006;72(4):381–386. ![]()

9. Feldon, P, Millender, LH, Nalebuff, EA. Rheumatoid arthritis in the hand and wrist. In: Green DP, ed. Operative Hand Surgery. 3rd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1993:1587–1690.

10. Blank, JE, Cassidy, C, The distal radioulnar joint in rheumatoid arthritis. Hand Clinics. 1996;12(3):499–513. ![]()

11. Bachdahl, M, The caput ulnae in rheumatoid arthritis: a study of the morphology, abnormal anatomy, and clinical picture. Acta Rheumatol Scand 1963; 5:1–75. ![]()

12. Straub, LR, Ranawat, CS, The wrist in rheumatoid arthritis – surgical treatment and results. J Bone Joint Surg 1969; 51A:1–20. ![]()

13. O’Donovan, TM, Ruby, LK, The distal radial ulna joint in rheumatoid arthritis. Hand Clinics 1989; 5:249–256. ![]()

14. Linscheid, RL, Biomechanism of the distal radioulnar joint. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1992; 275:46–55. ![]()

15. Kihara, H, Palmer, AK, Werner, FW, et al, The effect of dorsally angulated distal radius fractures on distal radioulnar joint congruency and forearm rotation. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1996;21(1):40–47. ![]()

16. Ishikawa, J, Iwasaki, N, Minami, A, Influence of distal radioulnar joint subluxation on restricted forearm rotation after distal radius fracture. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2005;30(6):1178–1184. ![]()

17. Lichtman, DM, Joshi, A, Acute injuries of the distal radioulnar joint and triangular fibrocartilage complex. Instr Course Lect 2003; 52:175–183. ![]()

18. Szabo, RM, Distal radioulnar joint instability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(4):884–894. ![]()

19. Palmer, AK, Triangular fibrocartilage complex lesions: a classification. J Hand Surg [Am] 1989; 14:594–606. ![]()

20. Palmer, AK. The distal radioulnar joint. In: Lichtman DM, ed. The Wrist and its Disorders. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1988:220–231.

21. Adams, BD, Samani, JE, Holley, KA, Triangular fibrocartilage injury: a laboratory model. J Hand Surg. 1996;21A(2):189–193. ![]()

22. Lindau, T, Adlercreutz, C, Aspenberg, P, Peripheral tears of the triangular fibrocartilage complex cause distal radioulnar joint instability after distal radial fractures. J Hand Surg. 2000;25A(3):464–468. ![]()

23. Chidgey, LK, The distal radioulnar joint: problems and solutions. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1995;3(2):95–109. ![]()

24. Loftus, JB, Palmer, AK. Disorders of the distal radioulnar joint and triangular fibrocartilage complex: an overview. In: Lichtman DM, Alexander AH, eds. The Wrist and its Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1997:385–414.

25. Yoshida, R, Beppu, M, Ishii, S, Hirata, K, Anatomical study of the distal radioulnar joint: degenerative changes and morphological measurement. Hand Surg. 1999;4(2):109–115. ![]()

26. Buterbaugh, GA, Brown, TR, Horn, PC, Ulnar-sided wrist pain in athletes. Clin Sports Med. 1998;17(3):567–583. ![]()

27. Ahn, AK, Chang, D, Plate, AM, Triangular fibrocartilage complex tears: a review. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2006;64(3–4):114–118. ![]()

28. Lester, B, Halbrecht, J, Levy, IM, Gaudinez, R, ‘Press test’ for office diagnosis of triangular fibrocartilage complex tears of the wrist. Ann Plast Surg. 1995;35(1):41–45. ![]()

29. Haims, AH, Moore, AE, Schweitzer, ME, et al, MRI in the diagnosis of cartilage injury in the wrist. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182(5):1267–1270. ![]()

30. Potter, HG, Asnis-Ernberg, L, Weiland, AJ, et al, The utility of high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of the triangular fibrocartilage complex of the wrist. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(11):1675–1684. ![]()

31. Chiou, HJ, Chang, CY, Chou, YH, et al, Triangular fibrocartilage of wrist: presentation on high resolution ultrasonography. J Ultrasound Med. 1998;17(1):41–48. ![]()

32. Stuart, PR, Berger, RA, Linscheid, RL, An, KN, The dorsopalmar stability of the distal radioulnar joint. J Hand Surg. 2000;25A(4):689–699. ![]()

33. Bedar, JM, Osterman, AL, The role of arthroscopy in the treatment of traumatic triangular fibrocartilage injuries. Hand Clinics. 1994;10(4):605–614. ![]()

34. Zelouf, DS, Bowers, WH. Treatment of acute injuries of the triangular fibrocartilage complex. In: Lichtman DM, Alexander AH, eds. The Wrist and its Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1997:415–428.

35. Bedar, JM, Arthroscopic treatment of triangular fibrocartilage tears. Hand Clinics. 1999;15(3):479–488. ![]()

36. Zelouf, DS, Bowers, WH, Arthroscopy of the distal radioulnar joint. Hand Clinics. 1999;15(3):475–477. ![]()

37. Berger, RA, Arthroscopic anatomy of the wrist and distal radioulnar joint. Hand Clinics. 1999;15(3):393–413. ![]()

38. Bowers, WH, Instability of the distal radioulnar articulation. Hand Clinics 1991; 7:311–327. ![]()

39. Minami, A, Kato, H, Ulna shortening for triangular fibrocartilage complex tears associated with ulnar positive variance. J Hand Surg. 1998;23A(5):904–908. ![]()

40. Beyermann, K, Krimmer, H, Lanz, U, TFCC (triangular fibrocartilage complex) lesions. Diagnosis and therapy. Der Orthopäde. 1999;28(10):891–898. ![]()

41. Terry, CL, Waters, PM, Triangular fibrocartilage injuries in pediatric and adolescent patients. J Hand Surg. 1998;23A(4):626–634. ![]()