Disorders of the inert structures

Capsular and non-capsular patterns

Capsular pattern

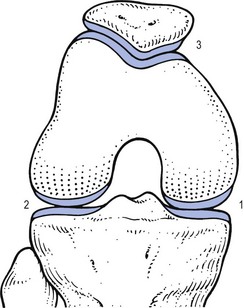

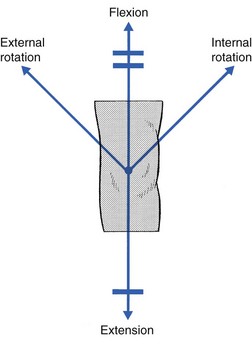

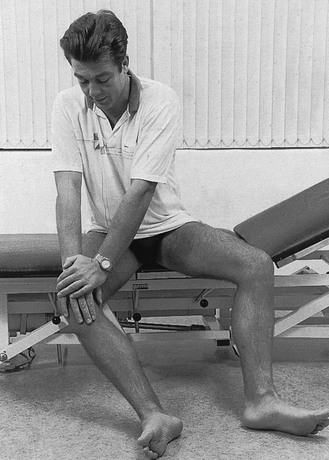

The normal capsular pattern at the knee joint is gross limitation of flexion and slight limitation of extension; the ratio of flexion : extension is roughly 1 : 10 (Fig. 52.1). Thus 5° of limited extension corresponds to 45–60° limitation of flexion and 10° to 90–100°. The range of rotation becomes restricted only in advanced arthritis. Recently, the concept of a capsular pattern of motion restriction at the knee was supported by a study of patients with inflamed knees.1

Fig 52.1 Capsular pattern at the knee joint.

Rheumatoid and reactive arthritis

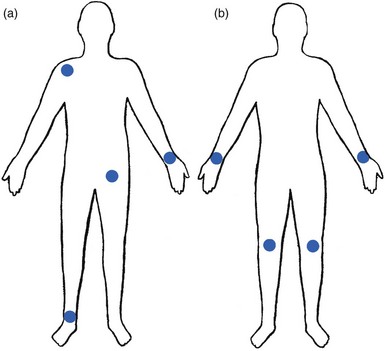

Rheumatoid arthritis is a common cause of knee inflammation. The symmetrical distribution of the affected joints is typical of this disease (Fig. 52.2).

Reactive arthritis is an inflammation of the joint secondary to a generalized infection but in which the articular fluid remains aseptic (Crohn’s disease, Reiter’s syndrome, aseptic gonococcal arthritis).2,3 The arthritis can remain monoarticular but may involve other joints in an asymmetrical manner.

In rheumatoid and reactive arthritis, intra-articular injections with triamcinolone give excellent but often only temporary results. Steroids injected into weight-bearing joints can cause arthropathy if injected too often.4,5 Therefore, injections must be restricted to two or three a year, which is enough to keep the patient comfortable. Nevertheless, considerable doubts about the dangers of repeated intra-articular steroid injections have arisen since a study report by Balch et al.6 They studied 65 patients with rheumatoid arthritis, who each received a minimum of 15 and a maximum of 167 injections at monthly intervals. Only two showed gross osteoarthrosis. These findings were confirmed later.7

Osteoarthrosis

The prime cause of gross degeneration in the knee joint is a disturbed distribution of load, which happens, for instance, when the patient suffers repeatedly from attacks of internal derangement because of a torn meniscus.8,9 Early osteoarthrosis will also occur if a valgus deformity is present from youth or there is an old malunited fracture that produces uneven load and repeated shearing strains. This also occurs if the meniscus is completely removed and its load-bearing function is therefore lost; the femoral condyles then exert pressure on the tibial platform over a much smaller area and the joint is apt to wear out rapidly.10,11 The knee is often affected in osteitis deformans and marked osteoarthrosis can then supervene. Aseptic necrosis of the medial condyle has been blamed as the cause of rapidly progressive, symptomatic osteoarthrosis in the elderly.12–14

The loss of articular cartilage, the structural changes of subchondral bone and the reactive osteophyte formation are the typical and well-known radiological appearances of progressive degenerative arthritis at the knee.15 It may be localized at the lateral, medial or patellofemoral compartment or may be generalized throughout the joint (Fig. 52.3).

Although osteoarthrosis at the knee is considered very common, its prevalence is overestimated. The reason is quite simple: radiographs taken in a middle-aged or elderly patients complaining of knee pain will always show some evidence of cartilaginous degeneration. As age advances, some narrowing of the joint space and osteophyte formation always appear; they are normal and cause no harm.16 Therefore the diagnosis of symptomatic osteoarthrosis should be made not by radiography but on the typical findings on clinical examination. A minor degree of osteoarthrosis does not give rise to symptoms and it is only when gross osteoarthrosis with disintegration of the cartilage supervenes that the complaints can be attributed to it. What commonly, but incorrectly, is labelled ‘osteoarthrosis’ is a monoarticular steroid-sensitive arthritis or an impacted loose body. Both occur in middle-aged or elderly patients with osteophytes showing radiologically, and the diagnosis is missed if full clinical examination is not carried out properly.

The treatment of osteoarthrosis is mainly with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and intra-articular injections with steroids. NSAIDs provide some relief of the symptoms but have clinically important side effects – they are estimated to cause 3300 deaths annually among the elderly in the US.17 Intra-articular injections with steroids also improve symptoms but the benefits are usually short-lived18,19 and there is always the potential for long-term joint deteriorations if injections are repeated too often. During the last decade, a number of promising reports on the effect of intra-articular injections with hyaluronic acid have been published. Hyaluronic acid is an important component of healthy synovial fluid and cartilage tissue; it is thought to protect the articular cartilage and soft tissue surfaces of the knee by acting as a lubricant and, because of its high viscosity, by imparting viscoelastic properties to the joint. Because intra-articular hyaluronic acid concentrations are lower in the synovial fluid of arthrotic knees,20 intra-articular injections with hyaluronic acid have been proposed as a means of restoring the viscoelastic properties of the knee joint, thereby providing symptom relief and improving joint function. Efficacy and safety of hyaluronic acid have been compared with that of saline,21–23 corticosteroids24 and NSAIDs. All the double-blind and randomized studies on the effect of hyaluronic acid on osteoarthrosis of the knee confirm that five intra-articular injections of sodium hyaluronate at weekly intervals are superior to placebo and are well tolerated in patients with osteoarthrosis of the knee, conferring a symptomatic benefit which persisted for 6 months.25–27 As hyaluronic acid seems to provide beneficial effects with minimal adverse reactions in a significant number of patients, it may be considered as a substantive addition to the therapeutic armamentarium in osteoarthrosis.

When the condition is too advanced, joint replacement is the only solution.

Monoarticular steroid-sensitive arthritis

Cyriax described a monoarticular arthritis in the knee having some similarities with monoarticular arthritis in the shoulder and elbow. The cause and pathogenesis of this arthritis remain unclear but it heals immediately and lastingly after two injections of triamcinolone, thus earning it the title of ‘steroid-sensitive’ arthritis (Cyriax28: p. 404).

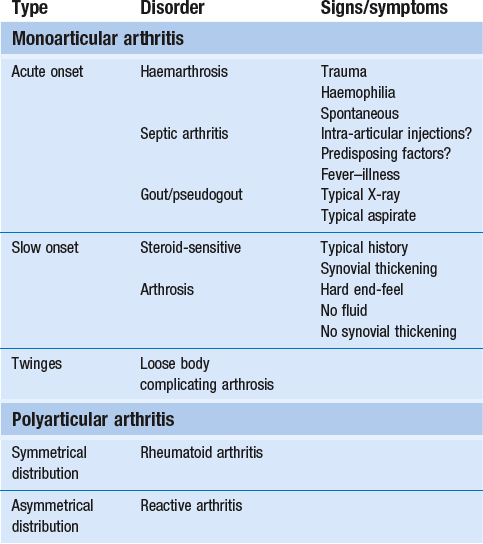

Differential diagnosis

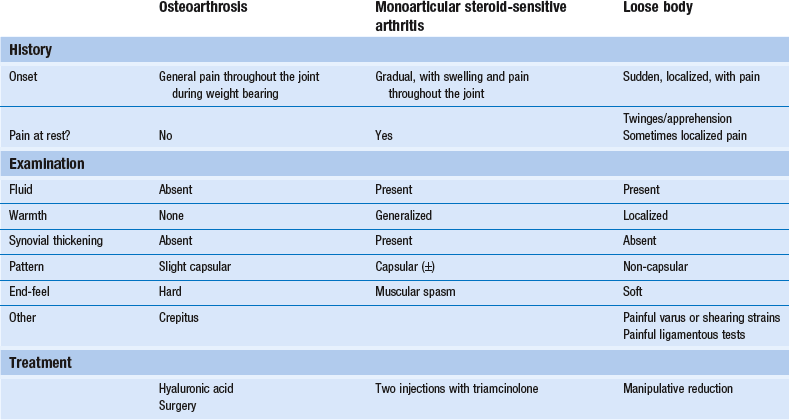

The differential diagnosis of a monoarticular steroid-sensitive arthritis, summarized in Table 52.1, must be made from the following conditions29:

• Polyarthritis: in monoarticular steroid-sensitive arthritis, disease does not spread to other joints and the laboratory findings remain normal, distinguishing it from rheumatoid and reactive arthritis.30,31

• Villonodular arthritis of Jaffé and Lichtenstein32 is an advanced arthritis, with marked synovial hyperplasia and thickening of the capsule.33 This type of arthritis is frequently complicated by spontaneous and recurrent haemarthrosis.34,35 In doubtful cases, arthroscopic biopsy is indicated.36 Treatment with steroid injections usually fails. Synovectomy is then advised.37 Good results have also been reported with intra-articular injections of thiotepa.38

• In middle age, a loose body complicating osteoarthrosis may be very difficult to distinguish. The distinct features of a loose body are sudden twinges, localized warmth and absence of synovial thickening. In long-standing arthritis, secondary wasting of the quadriceps muscle may make the knee feel weak and climbing stairs difficult; consequently, a complaint of twinges is not always a good sign. The only certain criterion may then be synovial thickening, which is not always ascertained easily, especially in middle-aged women, whose subcutaneous tissues are already somewhat thickened. In such circumstances, manipulation for a suspected loose body can be tried; if several attempts do not succeed, the joint should be injected.

• Gout and pseudogout have an acute onset with an immediate and gross articular pattern.

Treatment

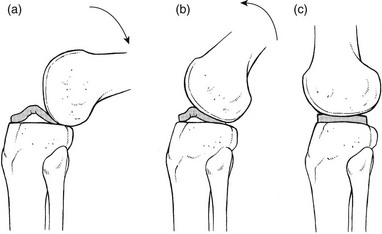

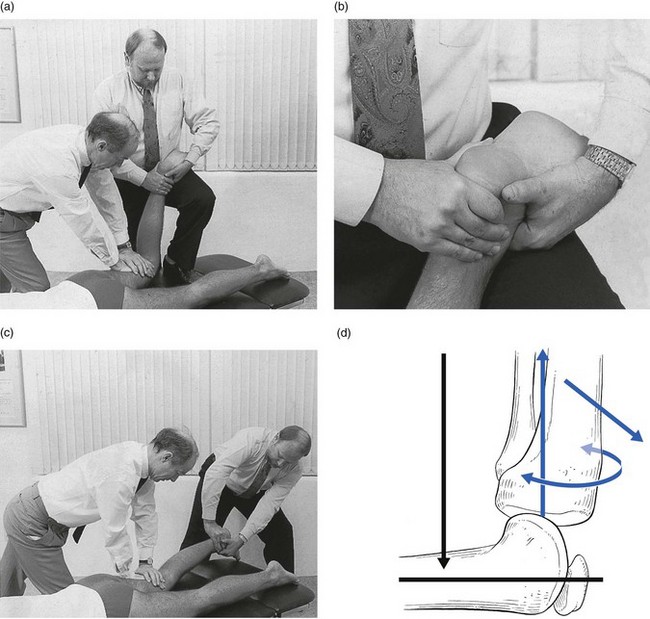

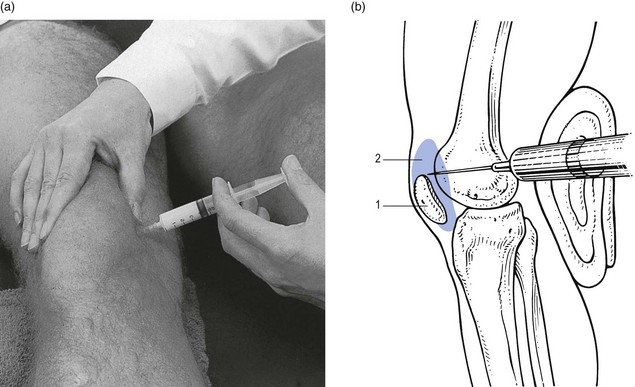

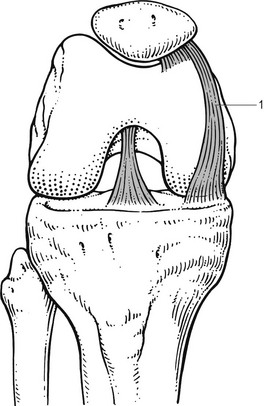

The treatment of monoarticular steroid-sensitive arthritis at the knee is two injections of 40 mg of triamcinolone at an interval of 2 weeks (Fig. 52.4).

Fig 52.4 Intra-articular injection of the knee. Structures in (b): 1, patella; 2, suprapatellar pouch.

Technique: injection for monoarticular steroid-sensitive arthritis![]()

The patient lies on the couch and relaxes the quadriceps muscle (Fig. 52.4a). If gross arthritis is present, it may be necessary to place a small cushion under the knee in order to keep it in slight flexion. The operator stands level with the other knee. With one hand the patella is pushed up and towards the operator, which makes the medial edge more prominent. A 5 mL syringe is filled with steroid suspension and fitted with a thin needle, 4 cm long, which is placed near the upper border of the patella and thrust in horizontally just between the patellar edge and the medial femoral condyle (Fig. 52.4b). It lies intra-articularly at about 2 cm depth.39

Crystal synovitis

Gout

An acute arthritis at the knee occurs in 25% of all attacks of gout.40 There is considerable pain, swelling and redness, which makes the condition difficult to differentiate from septic arthritis, haemarthrosis or pseudogout. Sometimes analysis of the joint fluid is necessary to distinguish these conditions.

Pseudogout

Calcium pyrophosphate crystals are believed to induce the synovitis of pseudogout. The term chondrocalcinosis refers to the presence of these calcium-containing salts in the articular cartilage,41 which are seen on radiographs.

The disease may be familial and is also commonly associated with a wide variety of metabolic disorders – for example, haemochromatosis, hyperparathyroidism, ochronosis and diabetes mellitus – and is also found in patients undergoing dialysis.42,43

Haemarthrosis

Post-traumatic haemarthrosis

This usually indicates a serious lesion, most commonly rupture of a cruciate ligament or an intra-articular fracture (see p. 599).44,45 Sometimes it is the result of a direct capsular contusion.46

The patient states that, after the injury, the knee became painfully swollen within 2–3 minutes. The speed of swelling, together with the severe pain, indicates an intra-articular haemorrhage; blood fills the joint at once and is a strong irritant. Blood left within the joint for weeks can cause severe arthritis and serious erosion of the articular cartilage. It should be removed at once.47–49 After a few days, it may be necessary to aspirate the remaining blood-tinged synovial effusion.

Spontaneous haemarthrosis in the elderly

Sudden pain and swelling without previous injury in an elderly patient will often be caused by an intra-articular haemorrhage, presumably as the result of the rupture of an intra-articular vein. Haemarthrosis should be suspected particularly when the patient is on anticoagulant therapy.50,51

Septic arthritis

Septic arthritis can follow haematogenous dissemination from focal infections, such as urethritis, cystitis, skin infections55 or dental abscesses. This is particularly so when resistance is decreased: diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, renal failure or a deficient immune system are all possible causes of decreased resistance.56 Intravenous drugs and gonococcal infections, particularly with antibiotic-resistant gonococci,57 have also been blamed for the increased incidence of septic arthritis of the knee. Another cause of septic arthritis is direct inoculation of organisms during intra-articular injection.

Treatment is with high doses of antibiotics intravenously and daily aspiration of the knee.58

Non-capsular pattern

Internal derangement

Introduction

A thorough clinical assessment can usually provide sufficient information to make a definitive diagnosis of internal derangement.59 Plain radiographs are of no use in the diagnosis of internal derangement. Arthroscopy may be useful but should never be performed without first completing a full preoperative examination.

Lesions of the meniscus

These can be grouped into congenital anomalies, traumatic conditions, cysts and metabolic disorders.

Congenital anomalies

The most common congenital anomaly with pathological sequelae is a discoid lateral meniscus. The incidence in autopsy specimens is between 0% and 7%,60 but most do not cause problems.61 Symptomatic disorder seems to occur only in the Wrisberg ligament type of discoid meniscus. This type is classically described as lacking a posterior capsular attachment and presents in childhood with a ‘snapping’ knee: the meniscus rolls up in front of the lateral compartment during flexion, as a consequence of increased friction and greater mobility; during extension, the rolled meniscus becomes trapped anteriorly, until it reduces suddenly with a dramatic audible snap (Fig. 52.5).62

The disorder affects children and adolescents. The presenting symptom is internal derangement at the lateral side of the knee. Clinical examination reveals an audible click and visible alteration of the knee at approximately 10–20° of extension.63 Diagnosis is confirmed with sonography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).64

Treatment of a congenital discoid meniscus is complete or partial meniscectomy.65

Traumatic meniscal lesions

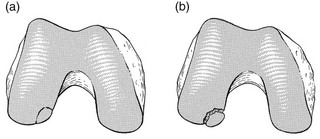

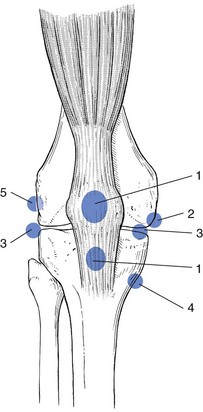

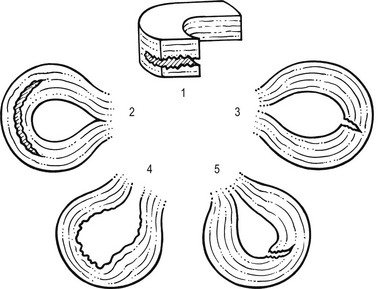

Disruption of collagen fibres within the meniscus occurs as the result of either an acute injury or gradual age-dependent degeneration (Fig. 52.6). The split may be either horizontal or vertical.

Fig 52.6 Main types of meniscal tear: 1, horizontal; 2, longitudinal; 3, radial; 4, degenerative; 5, flap.

Vertical tears

Vertical tears are the most important clinicopathological condition of the meniscus and usually result from excessive force applied to a normal meniscus. Transverse tears are less common than longitudinal ones. The latter frequently involve the thin inner edge of the meniscus, which, when it separates, creates the bucket-handle tear, so characteristic of the locking knee.66 Peripheral longitudinal tears are defined as those occurring within 3 mm of the meniscosynovial junction and comprise about 30% of all vertical tears.67 Left untreated, most of these peripheral lesions heal spontaneously.68

The less mobile medial meniscus is much more commonly involved than the lateral meniscus. The medial meniscus is closely bound to the medial collateral ligament and the medial coronary ligament, which attaches the meniscus to the tibia, is only 4–5 mm long. The lateral meniscus, however, is separated from the lateral collateral ligament by the popliteus tendon, and its coronary ligament is much longer (13–20 mm).8 This difference in mobility is the reason for the higher proportion of torn medial menisci.

The typical vertically torn meniscus, which results in a bucket-handle lesion, occurs between the ages of 15 and 30 years. The mechanism of injury is as follows: during flexion–extension, the menisci move with the tibia, to which they are attached (see online chapter Applied anatomy of the knee), but during rotational movements they follow the femoral condyles. During combined movements, the normal displacement of both menisci may be prevented and the menisci become trapped between tibia and femur. This typically happens in a football player who, in an attempt to kick the ball sideways, severely twists on the slightly flexed and weight-bearing knee: the rotation force of the femur on the immobilized tibia then ruptures the cartilage. It has also been suggested that meniscal lesions may appear as the result of knee instability, in particular after anterior cruciate lesions.69,70

Horizontal and posterior cracks

It is generally accepted that these lesions result from normal forces acting on a degenerating meniscus.71 Degenerative horizontal cleavage lesions are therefore more common in individuals of more than 40 years of age and usually occupy the posterior half of the menisci.72,73 They are so common that most authors regard them as part of the usual degenerative processes in the knee (Noble and Turner,74 Fahmy et al,75 Smillie9: pp. 79, 97, 108, 145, 153).

In a posterior crack, the history is less dramatic than in that of a vertical tear.72 For instance, the patient finds that, if there is a twist on the knee, something is occasionally felt to ‘give way’, usually at the back of the joint. It is immediately difficult to straighten the leg, but when it is shaken or kicked out, a click is heard and the limb returns to normal function. Sometimes the patient gives a different history: slight rotation and flexion during weight bearing – for example, on getting out of a car – produce an uncomfortable click which is relieved immediately on straightening the leg.

Diagnosis

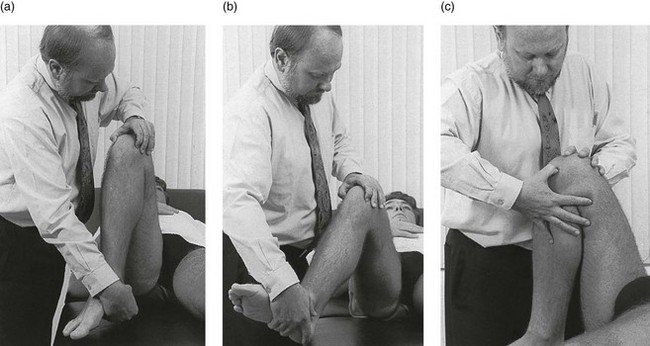

If the patient is seen some time after reduction of the meniscus, the knee may appear normal or merely shows a sprained coronary ligament. Alternatively, the patient presents with a history of a minor posterior crack but the routine functional examination is normal. In these cases, the following tests can be used to elicit signs of a ruptured meniscus (Fig. 52.7).

During recent decades, arthroscopy has made the diagnosis and treatment of a torn meniscus much easier.76,77 Nevertheless, arthroscopy does not make a clinical diagnosis redundant and routine arthroscopy without a previous thorough functional examination can lead to wrong conclusions and treatment. Because meniscal lesions are so common that they are a frequent finding in middle-aged people, it is very possible that a meniscal tear, found incidentally during ‘routine’ arthroscopy, is not the cause of the patient’s complaints. For instance, if a patient with a chronic ligamentous lesion of the medial collateral band or the coronary ligaments is subjected to arthroscopy before a clinical diagnosis has been made, the damaged meniscus will be blamed and thus unnecessarily removed.

The use of the arthroscope has encouraged the widespread assumption that the source of chronic pain in the area of the knee is to be found in the interior of the joint itself. The more likely cause of pain, however, is in the surrounding ligaments, but this can only be demonstrated by a thorough clinical assessment.78 We, like Goodfellow (‘He who hesitates is saved’),79 believe that, although meniscal tears can be detected by arthroscopy with almost 100% accuracy, caution is needed in ascribing symptoms at the knee to meniscal lesions. Diagnosis of meniscal lesions should be made clinically and arthroscopy should be reserved for confirmation of clinical findings as an aid in therapeutic decision making.

Treatment

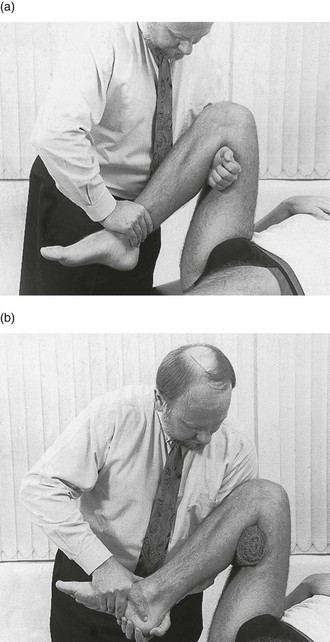

The hip is slightly rotated medially and strong valgus pressure is exerted at the knee (Fig. 52.8). In this position, repeated extensions are performed but not beyond the end of range – i.e. if the extension range is limited by 10°, the movement should stop at about 15°. In order to ensure this, the thumb placed in the popliteal fossa is used as a brake during the procedure. Once flexion and extension movements have been performed several times in this way, rapid to-and-fro rotations of the knee are added.

Natural history

The meniscal lesion itself causes no pain because the body of the meniscus is almost completely insensitive. Pain is the result of ligamentous strain caused by the repeated luxations and subluxations. However, damaged menisci frequently do not provoke any symptoms. In a postmortem study in patients above and below the age of 50, Noble and Hambden found that up to 60% of the former and 19% of the latter had meniscal tears.80,81

It is important to realize that most complaints following subluxation of a meniscus stem from a sprained coronary ligament. If a patient with a history of a former locked meniscus complains of persistent and localized pain but proves to have a full range of movement with a normal end-feel, a sprained coronary ligament should be suspected and appropriate treatment given. After successful manipulation, the reduced piece of cartilage may never subluxate again and the patient is cured for good. This was emphasized by Casscells,82 who stated that not all meniscal tears need surgical treatment. Asymptomatic meniscal tears identified at the time of arthroscopic examination for ligamentous lesions are best left in place or unrepaired, as they will remain asymptomatic.83 Furthermore, laboratory studies have demonstrated that torn menisci may have normal biomechanical function if the peripheral circumferential fibres remain intact.84,85

Surgery

Although surgery of the meniscus should not be undertaken lightly, it is unwise to permit repeated attacks of internal derangement because they initiate a premature, troublesome and intractable osteoarthrosis.75,86

The choice lies, then, between total or partial meniscectomy or repair. Total meniscectomy leads to loss of integrity of the articular cartilage and impairment of joint stability.87–91 It is no longer considered the treatment of choice because of increasing dissatisfaction with the long-term results.10,92 Instead, and if this is technically possible, only the loose fragment is removed and the outer part of the meniscus, together with the coronary ligament, is left alone.93 The result is no increase in weight-bearing stress on the tibia.94 The outer rim of the meniscus can still bear weight and thus preserve the articular cartilage, as well as play a useful role in stabilizing the joint. In experienced hands, this partial removal of the meniscus using arthroscopy is much less damaging to the joint and requires only 2 days’ bed rest. Subsequent return to work and sport is also quicker.95 Several long-term studies have demonstrated the technique’s superiority over total meniscectomy.96–100

In recent years, suturing of the relatively vascular outer edge of the meniscus has been shown to result in healing by fibrous tissue.101–107 Meniscal repair is nowadays considered as the treatment of choice in single, vertical, longitudinal tears in the outer third of the meniscal substance.108 Good to very good long-term results may be expected if the longitudinal tear is less than 3 cm long and within 3 mm of the periphery, and the meniscal tissue is not degenerating.109,110 Ligamentous instability is a relative contraindication to repair. In combination with insufficiency of the anterior cruciate ligament, the rate of retearing approaches 40% and therefore anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction should be performed at the same surgical intervention.111,112

Cysts of the meniscus

When cysts form, they are almost always at the lateral meniscus; a cyst of the medial meniscus is extremely rare.113 There is evidently a connection between cyst formation and the existence of ruptured menisci because half the cystic menisci are also torn.114

Clinical examination reveals a normal range of movement and a normal end-feel. Ligamentous tests are negative. When the joint line is palpated during full extension, the cyst is felt there as a small firm mass that varies in apparent size depending on the position of the knee, usually being most prominent in 20–30° of flexion and disappearing on full flexion (Pisani’s ‘disappearing’ sign).115 Some tenderness is elicited at the joint line and over the cyst. The diagnosis can be confirmed with MRI.116

Treatment is aspiration of the cyst. It is important to use a large-bore needle and to insert it in several different directions, as the cyst is often multilocular.117 Arthroscopic treatment is used if the cyst recurs.118–120

Metabolic disorders affecting the meniscus

The most important metabolic condition affecting the menisci is chondrocalcinosis. A recent random autopsy study found calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals in 7% of the menisci examined.121 Chondrocalcinosis of the meniscus is considered in the previous section of this chapter (‘Capsular pattern’).

Loose body in young patients

Osteochondritis dissecans is well known, although the true cause is still not completely understood. In those under the age of 13 years, the condition seems to result from an abnormality of ossification. In teenagers and adults, however, trauma may have a significant part to play in the development of the lesion.122,123 More than 75% of the osteochondral lesions are on the lateral side of the medial femoral condyle.124 About 10–15% are situated at the lateral femoral condyle and in less than 10% of the patients the lesions are bilateral.125

Few symptoms result, as long as the osteochondral lesion remains stable and embedded in the condyle (Fig. 52.9). There is some vague pain during weight bearing which can also be elicited during pressure over the medial condyle. Symptoms of intermittent pain and locking of the joint occur only when the fragment has become loose, which typically happens between 16 and 20 years of age.

After the attack of internal derangement, there are signs of a traumatic arthritis only: the knee is warm, contains some fluid and shows a slight capsular pattern. The ligamentous tests are normal and there is no local tenderness. Sometimes the loose body can be felt in the suprapatellar pouch. Wilson126 describes a test that aids in the diagnosis. The knee is flexed to a right angle and the tibia rotated internally; the examiner then slowly extends the patient’s knee. At about 30° of extension, pain may occur, presumably arising from the lesion at the inner condyle pressing against the tibial spine.

Stable osteochondritis dissecans has a successful healing rate of 50% after 6 months of relative rest.127 However, because the chance of spontaneous healing is low for juvenile osteochondritis dissecans lesions that present with disruption of the articular cartilage surface, and the risk of further damage is high, most surgeons recommend surgical stabilization of all unstable juvenile osteochondritis dissecans lesions at the time of presentation.128 The method used depends on the size of the defect and the congruity of the fragment with its bed. Sometimes replacement is tried, and sometimes removal of the loose fragments by arthroscope.129

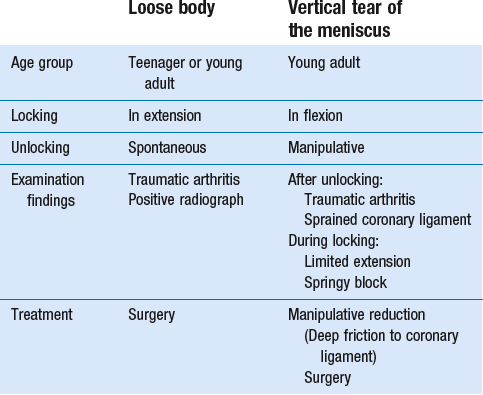

The differential diagnosis and treatment of loose body and meniscal tear in a young patient are summarized in Table 52.2.

Loose body complicating osteoarthrosis

Cyriax28 (his p. 403) pointed out that:

Contrary to popular belief, minor or moderate osteoarthritis at the knee does not cause symptoms.130 However, if there is some crepitating osteoarthritis, the articular cartilage is roughened. A small piece may then exfoliate. Alternatively, a small piece of degenerated meniscal cartilage may peel off and escape into the joint space. Such a loose fragment can occupy a harmless position at the back of the joint, or in the suprapatellar pouch, but sometimes impacts between the articular surfaces, where it occupies space, induces overstretching of the ligaments and causes localized pain.

Clinical examination

• Localized warmth: There is localized warmth on the painful side of the joint. If the joint is not warm at the beginning of the clinical examination, the examiner proceeds with the functional tests and repeats the palpation at the end. Local heat is then found which has been provoked by the minor stresses imposed on the joint during examination.

• Fluid: often, some fluid is present.

• Non-capsular pattern: there is usually a non-capsular pattern. It is obvious that when extension is limited by, e.g. 5° and flexion is not, or flexion is 30° limited but extension is of full range, a block due to internal derangement should be suspected. Such an obvious non-capsular pattern is rather uncommon and, as a rule, the signs are quite subtle. Extension is full but painful and has a smoother end-feel than on the opposite side, while flexion is full and painless. Alternatively, full extension is free from pain but flexion is slightly limited, with localized pain and a soft end-feel. In other words, the stop is not hard, as if muscle spasm due to arthritis was present, but feels as if it would go further, the limiting factor being pain.

• A varus movement hurts at the inner side of the joint: this indicates that a space-occupying lesion is present in the medial compartment. Alternatively, lateral or medial shearing strain may hurt at the inner or the outer side of the joint. Care should be taken not to press on the tender medial collateral ligament during these tests.

• Localized pain and positive ligamentous tests: there is localized pain at the end of range and some ligamentous tests are positive. As a rule, valgus strain and external rotation hurt at the medial side. The medial collateral ligament is also very tender to the touch. Usually these findings, together with localized warmth, fluid and absence of synovial thickening, are characteristic of a sprained ligament. However, the patient does not mention trauma. The conclusion is that, if the ligament is not being strained by external forces, the cause of the sprain must lie within the joint: the ligament becomes sprained when a small cartilaginous loose body is displaced between femoral condyle and tibial plateau, where it will put stress on the ligaments on every attempt to extend the joint. Cyriax called this ‘a sprain without a sprain’.

Special investigations

It is also apparently very difficult to see small loose bodies during diagnostic arthroscopy. It is striking, however, to hear that surgeons often see an improvement of symptoms and signs in an ‘arthrotic’ knee after such a procedure.131–133 In all likelihood, the loose bodies are washed out inadvertently during the drainage that is necessary for arthroscopic investigation and it is a consequence of this that the patient notices an improvement.

Differential diagnosis (Table 52.3)

Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee occurs in elderly patients, usually at the medial femoral condyle.12 The condition causes continuous pain which gets worse at night, but twinges are not mentioned. Clinical and radiological examinations are negative during the first few weeks of the condition’s development,134–136 and early diagnosis must be made by a bone scan137,138 or by the use of MRI. The treatment is proximal osteotomy or prosthetic replacement.139

Treatment

First manipulation

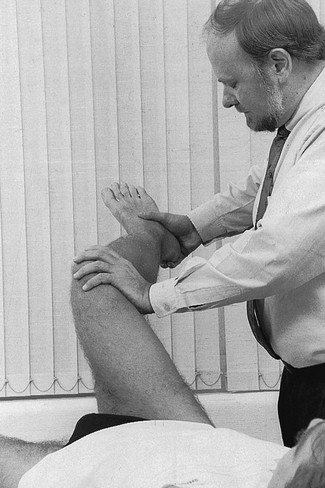

The principles of performing a manipulation for a loose body are:

• Traction should be as strong as possible.

• The manipulation starts with the ligaments in a relaxed position (knee in flexion).

• During movement towards extension, the knee is rotated three or four times, first in one direction and then, if no improvement results, in the other.

The patient lies prone on a low couch, the knee flexed to a right angle. An assistant holds the thigh just above the popliteal fossa. The manipulator stands level with the patient’s knee. The ipsilateral hand grasps the calcaneus. The other hand is placed at the dorsum of the foot in such a way that the second metacarpal bone presses against the neck of the talus (Fig. 52.10a). The pressure against the talus and the simultaneous traction on the calcaneus hold the foot in dorsiflexion during the whole procedure (Fig. 52.10b).

The manipulator now removes the leg from the couch and, leaning sideways towards the end of the couch, places the foot as distally (in relation to the patient) as possible (Fig. 52.10c). By doing so, maximum traction is ensured during the whole procedure. Extension is accompanied by a series of full lateral or medial rotations (Fig 52.10d). To this end, both shoulders and elbows must be used in order to reach the very end of rotation. The end-feel will once again be a guide in deciding whether the knee is at full range. In practice, rotation is tried first in one direction and then, if this does not succeed, in the other. The assistant who is holding the leg down feels a click, indicating that reduction has taken place, but the manipulator does not feel anything. After each manipulation, whether the knee has clicked or not, the joint is examined again. If there is improvement after a particular manœuvre, the same manipulation is done again.

Second manipulation

The patient lies supine on the couch. The manipulator places one wrist in the popliteal fossa, between tibia and femur, while the other hand presses at the distal end of the tibia. The knee is then bent as far as it will go (Fig. 52.11a). When progressive ligamentous resistance indicates that the slack has been taken up, the tibia is quickly forced into greater flexion with a small thrust. A click may be felt. Re-examination will show whether further reduction has taken place.

Fig 52.11 Second manipulation for a loose body impacted in the knee: two alternative methods are shown.

If this manipulation fails, the same movement can be repeated during rotation![]() . The manipulator places a firm rolled bandage in the popliteal fossa (Fig. 52.11b). This permits the patient’s foot and wrist to be held with both hands. Rotational movements can be added during the forced flexion. First one rotation is tried; should this fail, rotation in the opposite direction is attempted.

. The manipulator places a firm rolled bandage in the popliteal fossa (Fig. 52.11b). This permits the patient’s foot and wrist to be held with both hands. Rotational movements can be added during the forced flexion. First one rotation is tried; should this fail, rotation in the opposite direction is attempted.

Third manipulation

The patient lies supine. The manipulator stands level with the knee, and bends it to a right angle while the hip is flexed and laterally rotated. The hand is applied at the inner side of the knee and the other hand at the lateral border of the distal tibia in such a way that a strong varus movement is achieved (Fig. 52.12).

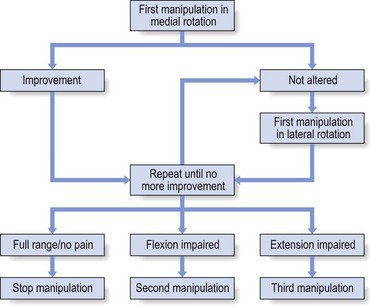

Once again, re-examination should follow each attempt and the end-feel will indicate whether reduction has taken place (Fig. 52.13).

Fig 52.13 Manipulative session for a loose body.

Instructions on after-treatment

During the following days the patient must repeat the manipulation several times a day. To do this, the patient sits on a low chair or on the ground, the knee flexed and the hip laterally rotated. The lateral border of the foot now rests on the floor. Pressing strongly on the inner side of the knee, and at the same time actively extending the leg, results in a varus movement during active extension (Fig. 52.14). Fixation of the lateral border of the foot against the floor ensures the counterpressure needed for a good varus stress. At nearly full extension, a small thrust is added.

Fig 52.14 After-treatment exercise by the patient.

Plica synovialis syndrome

Plicae synoviales are remnants of the embryological dividing walls in the knee. Arthroscopy has recently brought their existence to prominence. They are present in more than 20% of all knees,140 but it is only when pathological changes take place that pain and disability are likely to occur. Injuries and excessive strains are thought to be responsible for these pathological alterations.141,142

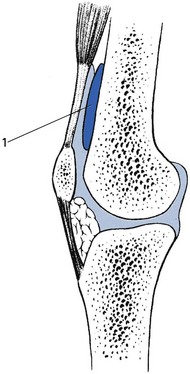

Although there are several types of synovial plicae, it is the plica mediopatellaris, or medial shelf (Fig. 52.15), which seems to cause most problems.143

Fig 52.15 Medial plica (1).

This plica was first described by Iino in 1939.144 It has its origin on the medial wall of the knee joint and runs obliquely down towards the synovium, inserting into it and covering the medial infrapatellar fat pad. During flexion it glides over the medial condyle like a wiper over a windscreen, which in normal circumstances is harmless and painless; if the plica is pathologically altered or the medial condyle has undergone arthrotic changes, however, symptoms may result.

One of these symptoms is a sudden twinge when the inflamed plica is pinched between the patella and the medial condyle of the femur. Sometimes there is pain and a slightly modified end-feel at the end of extension. A painful arc during flexion–extension can occur when a damaged and thickened plica rides over a chondral defect at the medial condyle, and it can be aggravated when this movement is performed during lateral rotation.145,146

The clinical diagnosis of a symptomatic medial plica is made from a history of localized pain during flexion–extension or pain at the end of extension.147 The plica can sometimes be felt if the examiner rolls the medial capsule of a slightly (45°) flexed knee under the thumb.148 When this rolling is painful, 20 mg of triamcinolone is locally infiltrated.149,150 Some authors have reported good to fair results with flexibility training of the flexor and extensor muscles of the knee.150,151 If the symptoms persist, arthroscopic resection is performed.152

Because the presence of a medial shelf is normal,153 one should be cautious in ascribing symptoms to it. The diagnosis should be made clinically and not by relying on accidental findings during arthroscopy.

Subsynovial haematoma

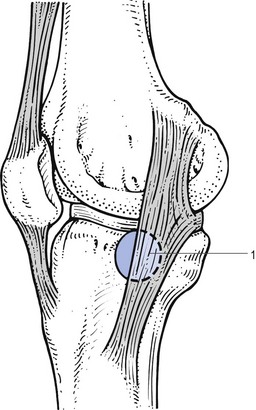

A severe blow on the front of the thigh may cause a localized haematoma between the suprapatellar pouch and the front of the femur (Fig. 52.16). Flexion is limited but extension remains free.

Fig 52.16 Subsynovial haematoma (1).

Posterior capsular strain

Treatment consists of infiltration with triamcinolone at the appropriate side, using the same technique as for posterior strains of the posterior cruciate ligament (see p. 709).

Cysts and bursitis

It is important to note that localized swellings may limit movements in a non-capsular way (Fig. 52.17). For example, a bursa underlying the medial collateral ligament, a prepatellar bursa or a cyst under the iliotibial tract can each cause a specific pattern.

Medial collateral ligament bursitis

The patient is usually middle-aged and complains of localized pain at the medial side of the knee, which has appeared without a specific cause (Fig. 52.18). The pain is worse during activity and eases at rest, but nocturnal pain may occur. There is no symptomatic evidence of internal derangement, such as twinges, locking and fear of giving way.154 Spontaneous cure is uncommon155: one of our patients had had unchanged symptoms for more than 6 years.

Fig 52.18 Medial collateral ligament bursitis (1).

Clinical examination reveals a cold joint, with no fluid or synovial thickening. Extension is normal, while flexion is limited by 15–45°. The end-feel is soft, the limiting factor being pain, which is strictly confined to the inner side of the knee. Valgus strain and lateral rotation are painful. Palpation reveals a solid swelling under the medial collateral ligament, level with the joint, which can be so hard that it is mistaken for a large osteophyte. Unlike a cyst of the meniscus, the bulge does not disappear during flexion, but enlarges and becomes firmer, especially when it lies at the dorsal aspect of the ligament.156

It is important to differentiate between chronic ligamentous sprain and bursitis under the medial collateral ligament, the signs of which are very similar. In sprain, the distinctive factors are a history of previous trauma and absence of palpable swelling. The treatment required – deep friction and manipulation – would undoubtedly worsen bursitis, and therefore the differential diagnosis should be made carefully. In case of doubt, MRI can demonstrate the fluid collection under the medial collateral band very well.157

Treatment is aspiration. A thick needle (19G × 4 cm) should be used because the fluid is so viscous that it is very difficult to remove. Injecting 10–20 mg of triamcinolone into the cavity will prevent early recurrence of symptoms. After aspiration, immediate full and painless flexion is possible. Permanent cure is often achieved.158

Patellar bursitis

The patient complains of pain and swelling in front of the knee. The diagnosis is made on simple inspection. If the swelling is gross, it can result in limitation of flexion because of the painful stretching of bursa and skin. Palpation shows that the effusion lies between skin and patella. The presence of heat suggests haemorrhage into the bursa, whereas heat and redness indicate the possibility of sepsis.159

Aspiration should be performed to disclose the nature of the fluid. If the bursa refills repeatedly, surgical removal must be considered.160

Bursa between the iliotibial tract and the lateral epicondyle

Aspiration, followed by local infiltration with corticosteroid suspension, is the remedy. If the condition fails to respond to this treatment, the posterior 2 cm of the band should be transversely sectioned.161

Pes anserinus bursitis

The pes anserinus bursa is situated between the medial collateral ligament and the overlying pes anserinus (tendons of sartorius, gracilis and semitendinosus).162 Inflammation of this bursa commonly occurs in long-distance runners.163

Clinical examination reveals a full range of movement. Sometimes resisted flexion and medial rotation cause pain because these movements squeeze the bursa painfully. A tender mass can be palpated at the tibial insertion of the medial collateral ligament.164

Treatment is local aspiration and infiltration with triamcinolone.165

References

1. Fritz, JM, Delitto, A, Erhard, RE, Roman, M, An examination of the selective tissue tension scheme; with evidence for the concept of a capsular pattern of the knee. Phys Ther 1998; 78:1046–1056. ![]()

2. Haslock, I, Wright, V. The arthritis associated with intestinal disease. Bull Rheum Dis. 1973; 32:479.

3. Mielants, H, Veys, EM, Reiter’s syndrome and reactive arthritis. New Engl J Med 1984; 310:1538. ![]()

4. Chandler, GN, Jones, DT, Wright, V, Charcot’s arthropathy following intra-articular hydrocortisone. BMJ 1959; 1:952–953. ![]()

5. Ishikawa, K. A study of deleterious effects of intra-articular corticosteroid on knee joints – a clinical investigation on primary gon-arthrosis. J Jap Orthop Ass. 1978; 52(3):359–374.

6. Balch, HW, Gibson, JMC, El-Ghobarey, E, et al. Steroid injections into knee. Rheumatol Rehab. 1977; 16:137.

7. Gray, RG, Gottlieb, NL, Intra-articular corticosteroids: an updated assessment. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1983; 177:235–263. ![]()

8. Seedhom, BB, Loadbearing function of the menisci. Physiotherapy. 1976;62(7):223–226. ![]()

9. Smillie, IS. Injuries of the Knee Joint. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1978.

10. Jackson, JP, Degenerative changes in the knee after meniscectomy. BMJ 1968; 2:525–527. ![]()

11. Seedhom, BB. Can footballers play well without their cartilages? Medisport. 1980; 2:98.

12. Albäck, S, Bauer, G, Bohne, WH, Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum 1968; 9:705–733. ![]()

13. Aglieti, P, Insall, JN, Bussi, R, Deschamps, C, Idiopathic osteonecrosis of the knee. Aetiology, prognosis and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg. 1983;65B(5):588–597. ![]()

14. Rozing, PM, De Jonge-Bok, JM, Idiopathische osteonecrose van de mediale femurcondyl: een zeldzame oorzaak van pijn in de knie bij een oudere patient. Ned Tidschr Geneeskd. 1983;127(19):809–811. ![]()

15. Gunther, KP, Scharf, HP, Standardization of roentgen diagnosis in coxarthrosis and gonarthrosis in clinical studies. Recommendations of the 1st Working Circle of the DGOT. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1997;135(3):193–196. ![]()

16. Kornaat, PR, Bloem, JL, Ceulemans, RY, et al, Osteoarthritis of the knee: association between clinical features and MR imaging findings. Radiology. 2006;239(3):811–817. ![]()

17. Griffin, MR, Epidemiology of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-associated gastrointestinal injury. Am J Med. 1998;104(Suppl. 3):23S–29S. ![]()

18. Jones, A, Doherty, M, Intra-articular corticosteroids are effective in osteoarthritis but there are no clinical predictors of response. Ann Rheum Dis 1996; 55:829–832. ![]()

19. Habib, GS, Saliba, W, Nashashibi, M, Local effects of intra-articular corticosteroids. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29(4):347–356. ![]()

20. Balazs, E, Denlinger, JL, Viscosupplementation: a new concept in the treatment of osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 1993;39(Suppl.):10–15. ![]()

21. Wobig, M, Dickhut, A, Maier, R, Vetter, G, Viscosupplementation with hylan G-F 20: a 26-week controlled trial of efficacy and safety in the osteoarthritic knee. Clin Ther. 1998;20(3):410–423. ![]()

22. Lohmander, LS, Dalen, N, Englund, G, et al, Intra-articular hyaluronan injections in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled multicentre trial. Hyaluronan Multicentre Trial Group. Ann Rheum Dis. 1996;55(7):424–431. ![]()

23. Altman, RD, Moskowitz, R, Intraarticular sodium hyaluronate (Hyalgan) in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized clinical trial. Hyalgan Study Group. J Rheumatol. 1998;25(11):2203–2212. ![]()

24. Frizziero, L, Govoni, E, Bacchini, P, Intra-articular hyaluronic acid in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: clinical and morphological study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1998;16(4):441–449. ![]()

25. Moskowitz, RW, Hyaluronic acid supplementation. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2000;2(6):466–471. ![]()

26. Huskisson, EC, Donnelly, S, Hyaluronic acid in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Rheumatology. 1999;38(7):602–607. ![]()

27. Petrella, RJ, Petrella, M, A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled study to evaluate the efficacy of intraarticular hyaluronic acid for osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(5):951–956. ![]()

28. Cyriax, JH, 8th ed. Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine; vol. 1. Baillière Tindall, London, 1982.

29. Fletcher, MR, Scott, JT, Chronic monarticular synovitis. Diagnostic and prognostic features. Ann Rheum Dis 1975; 34:171. ![]()

30. Auquier, L, Cohen de Lara, A, Siaud, JR, Devenir de 173 monoarthrites et monoarthropathies d’allure inflammatoire. Rev Rhum 1973; 40:125. ![]()

31. Iguchi, T, Matsubara, T, Kawai, K, Hirohata, K, Clinical and histological observations of monoarthritis. Anticipation of its progression to rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Orthop 1990; 250:241–249. ![]()

32. Jaffé, HL, Lichtenstein, L, Sutro, CJ. Pigmented villonodular synovitis. Arch Path. 1941; 31:731–765.

33. Wyllie, JC, The stromal cell reaction of pigmented villonodular synovitis: an electron microscopic study. Arthr Rheum 1969; 12:205–214. ![]()

34. D’Eshougues, JR, Delcambre, B, Leonardelli, J, et al, Hemarthrose du genou: par chondrocalcinose ou par synovite villonodulaire? Rev Rhum 1976; 43:309–310. ![]()

35. Chappel, R, Mortier, G, Herregods, P, et al. Gepigmenteerde villonodulaire synovitis: een niet zo zeldzame oorzaak van rcidiverende haemarthrose van de knie. Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1983; 39(18):1141–1144.

36. Henry, AN, Arthroscopy in practice. BMJ 1977; i:87. ![]()

37. Granowitz, SP, Mankin, HJ, Localized pigmented villonodular synovitis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg 1967; 49A:122–128. ![]()

38. Cloud, SR. Intra-articular thiotepa held effective in pigmented villonodular synovitis. American Rheumatology Association Western Region Meeting. Wellcome Trends Rheum. 3(2), 1981.

39. Goss, JA, Adams, RF, Local injections of corticosteroids in rheumatic diseases. J Musculoskeletal Med. 1993;(Mar)):83–92.

40. Dieppe, PA, Calvent, P. Crystals and Joint Disease. London: Chapman & Hall; 1983.

41. Moskowitz, RW, Garcia, F, Chondrocalcinosis articularis (pseudogout syndrome). Arch Intern Med 1973; 132:87. ![]()

42. Caner, JE, Decker, JL, Recurrent acute arthritis in chronic renal failure treated by haemodialysis. Am J Med 1964; 36:571. ![]()

43. Ramonda, R, Musacchio, E, Perissinotto, E, et al, Prevalence of chondrocalcinosis in Italian subjects from northeastern Italy. The Pro.V.A. (PROgetto Veneto Anziani) study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27(6):981–984. ![]()

44. Passler, J, Fellinger, M, Seggl, W, Der posttraumatische Hämarthros des Kniegelenkes – eine Indikation zur Arthroskopie. Akt Traumatol 1989; 19:135–138. ![]()

45. Bomberg, BC, McGinty, JB, Acute hemarthrosis of the knee: indications for diagnostic arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 1990;6(3):221–225. ![]()

46. Maffulli, N, Binfield, PM, King, JB, Good, CJ, Acute haemarthrosis of the knee in athletes. A prospective study of 106 cases. J Bone Joint Surg 1993; 75B:945–949. ![]()

47. Dustmann, HO, Knorpelveränderungen beim Hämarthros unter besonderen Berücksichtigiung der Ruhigstellung. Arch Orthop Unfallchirurg 1971; 71:148. ![]()

48. Convery, FR, Experimental hemarthrosis in the knee of the mature canine. Arthritis Rheum 1976; 19:59–67. ![]()

49. Cotta, H, Puhl, W, Niethard, FU, Der Einfluss des Hämarthros auf den Knorpel der Gelenke. Unfallchir 1982; 8:145–151. ![]()

50. Riley, SA, Spencer, GE, Jr., Destructive monarticular arthritis secondary to anticoagulant therapy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1987; 223:247–251. ![]()

51. Ross, MD, Elliott, R, Acute knee haemarthrosis: a case report describing diagnosis and management for a patient on anticoagulation medication. Physiother Res Int. 2011;16(2):120–123. ![]()

52. Phelip, X, Verdier, JM, Gras, JP, et al, Les Hémarthroses de la chondrocalcinose articulaire. Rev Rhum 1976; 43:259–266. ![]()

53. Ottaviani, S, Ayral, X, Dougados, M, Gossec, L, Pigmented villonodular synovitis: a retrospective single-center study of 122 cases and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;40(6):539–546. ![]()

54. Moskovich, R, Parisien, JS, Localized pigmented villonodular synovitis of the knee. Arthroscopic treatment. Clin Orthop 1991; 271:218–224. ![]()

55. Goldenberg, DL, Reed, JI, Bacterial arthritis. N Engl J Med 1985; 312:764–769. ![]()

56. Meijers, KA, Dijkmans, BA, Hermans, J, et al, Non-gonococcal infectious arthritis: a retrospective study. J Infect 1987; 14:13–20. ![]()

57. Goldenberg, DL, Cohen, AS, Acute infectious arthritis: a review of patients with nongonococcal joint infections. Am J Med 1976; 60:369. ![]()

58. Mielants, H, Dhondt, E, Goethals, L, et al, Long-term functional results of non-surgical treatment of common bacterial infections of joints. Scand J Rheumatol 1981; 11:101. ![]()

59. Terry, GC, Tagert, BE, Young, MJ, Reliability of the clinical assessment in predicting the cause of internal derangement of the knee. Arthroscopy 1995; 11:568–576. ![]()

60. Jeannopoulos, CL, Observation of discoid menisci. J Bone Joint Surg 1950; 32A:649–652. ![]()

61. Dickhaut, SC, Delee, JC, The discoid lateral meniscus syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg 1982; 64A:1068–1073. ![]()

62. Woods, GW, Whelan, JM, Discoid meniscus. Clin Sports Med. 1990;9(3):695–706. ![]()

63. Yaniv, M, Blumberg, N, The discoid meniscus. J Child Orthop. 2007;1(2):89–96. ![]()

64. Samoto, N, Kozuma, M, Tokuhisa, T, Kobayashi, K, Diagnosis of discoid lateral meniscus of the knee on MR imaging. Magn Reson Imaging 2002; 20:59–64. ![]()

65. Kobayashi, A. Discoid meniscus of the knee joint. Clin Orthop Surg Jpn. 1975; 10:10–24.

66. Bullough, PG, Vosburgh, F, Arnoczky, SP, Levy, IM. The menisci of the knee. In: Insall J, ed. Surgery of the Knee. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1984:135.

67. Poehling, GG, Ruch, DS, Chabon, SJ, The landscape of meniscal injuries. Clin Sports Med. 1990;9(3):539–549. ![]()

68. Weiss, CB, Lundberg, M, Hamberg, P, et al, Non-operative treatment of meniscal tears. J Bone Joint Surg 1989; 71A:811. ![]()

69. Satku, K, Kumar, JP, Ngoi, SS, Anterior cruciate ligament injuries: to counsel or operate? J Bone Joint Surg 1986; 68B:458–461. ![]()

70. Bray, RC, Dandy, DJ, Meniscal lesions and chronic anterior cruciate ligament deficiency. J Bone Joint Surg 1989; 71B:128–130. ![]()

71. Egner, E, Knee joint meniscal degeneration as it relates to tissue fiber structure and mechanical resistance. Pathol Res Pract 1982; 173:310. ![]()

72. Smillie, IS, The current pattern of internal derangements of the knee joint relative to the menisci. Clin Orthop 1967; 51:117. ![]()

73. Hadfield, G, Immobile meniscus syndrome. Proc R Soc Med 1966; 59:117. ![]()

74. Noble, J, Turner, P, The function, pathology and surgery of the meniscus. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1986; 210:62–68. ![]()

75. Fahmy, NR, Williams, E, Noble, J, Meniscal pathology and osteoarthrosis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg 1983; 65B:24. ![]()

76. Dandy, DJ. Arthroscopic Surgery of the Knee. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1981.

77. McGinty, JB, Matza, RA, Arthroscopy of the knee. Evaluation of an out-patient procedure under local anaesthetic. J Bone Joint Surg 1978; 60A:787–789. ![]()

78. Casscells, SW, Technology: a good servant but a bad master. Arthroscopy. 1990;6(1):1–2. ![]()

79. Goodfellow, J, He who hesitates is saved ’. J Bone Joint Surg 1980; 62B:1–2. ![]()

80. Noble, J, Hambden, DL, The pathology of the degenerate meniscus lesion. J Bone Joint Surg 1975; 57B:180. ![]()

81. Noble, J, Lesions of the menisci. J Bone Joint Surg 1977; 59A:480. ![]()

82. Casscells, SW, The place of arthroscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of internal derangement of the knee: an analysis of 1000 cases. Clin Orthop 1980; 151:135. ![]()

83. Fitzgibbons, RE, Shelbourne, KD, ‘Aggressive’ nontreatment of lateral meniscal tears seen during anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(2):156–159. ![]()

84. Hargreaves, DJ, Seedhom, BB. On the ‘bucket handle’ tear: partial or total meniscectomy? A quantitative study. J Bone Joint Surg. 1979; 61B:381.

85. Bourne, RB, Finlay, JB, Papadopoulos, P, Andreae, P, The effect of medial meniscectomy on strain distribution in the proximal part of the tibia. J Bone Joint Surg 1984; 66B:1431. ![]()

86. Walker, PS, Erkman, MJ, The role of the menisci in force transmission across the knee. Clin Orthop 1975; 109:184–192. ![]()

87. Dandy, DJ, Jackson, RW, The diagnosis of problems after meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg. 1975;57B(3):349–352. ![]()

88. Johnson, RJ, Kettelkamp, DB, Clark, W, Leaverton, P, Factors affecting later results after meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg 1974; 56A:712–729. ![]()

89. Noble, J, Erat, K, In defence of the meniscus: a prospective study of two hundred meniscectomy patients. J Bone Joint Surg. 1980;62(B):6–11. ![]()

90. Floman, Y, Eyre, DR, Glincher, MJ, Induction of osteoarthrosis in the rabbit knee joint: biomechanical studies on the articular cartilage. Clin Orthop 1980; 147:278. ![]()

91. Glosh, P, Sutherland, JM, Taylor, TKF, et al, The effects of post-operative joint immobilization of articular cartilage degeneration, following meniscectomy. J Surg Res 1983; 35:461. ![]()

92. Neyret, P, Donell, ST, Dejour, D, Dejour, H, Partial meniscectomy and anterior ligament rupture in soccer players; a study with a minimum 20 year follow-up. Am J Sports Med 1993; 21:455–460. ![]()

93. Burke, DL, Ahmed, AM. Biomechanical study of partial and total medial meniscectomy of the knee. Trans Orthop Res Soc. 1978; 3:91.

94. Bourne, R. Menisci distribute weight. Med Post. 1980; 16:29.

95. Dandy, DJ, Early results of closed partial meniscectomy. BMJ 1978; ii:1099. ![]()

96. Jackson, RW, Dandy, DJ. Partial meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg. 1976; 58(B):142.

97. McGinty, JB, Guess, LF, Marvin, RA, Partial or total meniscectomy. A comparative analysis. J Bone Joint Surg 1977; 59A:763–766. ![]()

98. Northmore-Ball, MD, Dandy, DJ, Jackson, RW, Arthroscopic, open partial and total meniscectomy: a comparative study. J Bone Joint Surg 1983; 65B:400. ![]()

99. Lyshom, J, Gillquist, J, Endoscopic meniscectomy – a follow-up study. Int Orthop 1981; 5:265–270. ![]()

100. Hamberg, P, Gillquist, J, Lysholm, J, A comparison between arthroscopic meniscectomy and modified open meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg 1984; 66B:189–192. ![]()

101. Cassidy, RE, Shaffer, AJ, Repair of peripheral meniscus tears. A preliminary report. Am J Sports Med 1981; 9:209–214. ![]()

102. De Haven, KE. Peripheral meniscus repair. An alternative to meniscectomy. Orthop Trans. 1981; 5:399–400.

103. Hennings, CE. Arthroscopic repair of meniscus tears. Orthopedics. 1983; 6:1130.

104. Rosenberg, TD, Scott, SM, Coward, DB, et al, Arthroscopic meniscal repair evaluated with repeat arthroscopy. Arthroscopy 1986; 2:14. ![]()

105. Barber, FA, Stone, RG, Meniscal repair, an arthroscopic technique. J Bone Joint Surg 1985; 67B:39–v41. ![]()

106. Albrecht-Olsen, PM, Bak, K, Arthroscopic repair of the bucket-handle meniscus. 10 failures in 27 stable knees followed for 3 years. Acta Orthop Scand 1993; 64:446–448. ![]()

107. Hamberg, P, Gillquist, J, Lysholm, J, Suture of new and old peripheral meniscus tears. J Bone Joint Surg. 1983;65A(2):120–124. ![]()

108. Shelbourne, KD, Porter, DA, Meniscal repair. Description of a surgical technique. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21(6):870–872. ![]()

109. Logan, M, Watts, M, Owen, J, Myers, P, Meniscal repair in the elite athlete: results of 45 repairs with a minimum 5-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(6):1131–1134. ![]()

110. Eggli, S, Wegmuller, H, Kosina, J, et al, Long-term results of arthroscopic meniscal repair: an analysis of isolated tears. Am J Sports Med 1995; 23:715–720. ![]()

111. DeHaven, KE, Lohrer, WA, Lovelock, JE, Long-term results of open meniscal repair. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(5):524–530. ![]()

112. Toman, CV, Dunn, WR, Spindler, KP, et al, Success of meniscal repair at anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(6):1111–1115. ![]()

113. Bonnin, JG, Cysts of the semilunar cartilages of the knee joint. Br J Surg 1953; 40:558–565. ![]()

114. Wroblenski, BM, Trauma and the cystic meniscus: review of 500 cases. Injury 1973; 4:319–321. ![]()

115. Pisani, AJ, Pathognomonic sign for cyst of the knee cartilage. Arch Surg 1947; 54:188. ![]()

116. Tyson, LL, Daughters, TC, Jr., Ryu, RK, Crues, JV, 3rd., MRI appearance of meniscal cysts. Skeletal Radiol. 1995;24(6):421–424. ![]()

117. Lantz, B, Singer, KM, Meniscal cysts. Clin Sports Med 1990; 9:707–725. ![]()

118. Seger, BM, Woods, WG, Arthroscopic management of lateral meniscus cysts. Am J Sports Med 1986; 14:105. ![]()

119. Pariesien, JS, Arthroscopic treatment of cysts of the menisci. Clin Orthop 1990; 257:154–158. ![]()

120. Tudisco, C, Meo, A, Blasucci, C, Ippolito, E, Arthroscopic treatment of lateral meniscal cysts using an outside-in technique. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(5):683–686. ![]()

121. Mitrovic, D, Stankovic, A, Borda-Iriarte, O, et al, Résultats de l’examen autopsique des cartilages des genoux chez 120 sujets décédés en milieu hospitalier. Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic 1987; 54:15. ![]()

122. MacNicol, MF. The Problem Knee: Diagnosis and Management in the Younger Patient. London: Heinemann; 1986.

123. Bradley, J, Dandy, DJ, Osteochondritis dissecans and other lesions of the femoral condyles. J Bone Joint Surg 1989; 71B:518–522. ![]()

124. Aircroth, PM, Osteochondritis dissecans of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg 1971; 32B:440–447. ![]()

125. Greenspan, A. Orthopaedic Radiology: A Practical Approach. New York: Raven Press; 1992.

126. Wilson, JN, Wilson’s sign. A diagnostic sign in osteochondrosis dissecans of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg 1967; 49A:477. ![]()

127. Wall, EJ, Vourazeris, J, Myer, GD, et al, The healing potential of stable juvenile osteochondritis dissecans knee lesions. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(12):2655–2664. ![]()

128. Kocher, MS, Tucker, R, Ganley, TJ, Flynn, JM, Management of osteochondritis dissecans of the knee: current concepts review. Am J Sports Med 2006; 34:1181–1191. ![]()

129. Anderson, AF, Pagnani, MJ, Osteochondritis dissecans of the femoral condyles: long-term results of excision of the fragment. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25(6):830–834. ![]()

130. Kornaat, PR, Bloem, JL, Ceulemans, RY, et al, Osteoarthritis of the knee: association between clinical features and MR imaging findings. Radiology. 2006;239(3):811–817. ![]()

131. Steadman, JR, Ramappa, AJ, Maxwell, RB, Briggs, KK, An arthroscopic treatment regimen for osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(9):948–955. ![]()

132. Stuart, MJ, Lubowitz, JH, What, if any, are the indications for arthroscopic debridement of the osteoarthritic knee? Arthroscopy. 2006;22(3):238–239. ![]()

133. Guhl, FG, Operative arthroscopy. Am J Sports Med. 1979;7(6):328–335. ![]()

134. Lotke, PA, Ecker, ML, Osteonecrosis of the knee. Current concepts review. J Bone Joint Surg. 1988;70A(3):470–473. ![]()

135. Lotke, PA, Ecker, ML, Osteonecrosis of the knee. Orthop Clin North Am 1985; 16:797–808. ![]()

136. Marmor, L, Osteonecrosis of the knee. Lateral and medial involvement. Clin Orthop 1984; 185:195–196. ![]()

137. Bauer, GCH, Smith, EM, Sr., Scintimetry in osteoarthritis of the knee. J Nucl Med 1969; 10:109–116. ![]()

138. Insall, JN, Aglietti, P, Bullough, PG. Osteonecrosis. In: Insall JN, ed. Surgery of the Knee. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1984:527–549.

139. Koshino, T, The treatment of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee by high tibial osteotomy with and without bone-grafting or drilling of the lesion. J Bone Joint Surg 1982; 64A:47–58. ![]()

140. Hardaker, WT, Whipple, TL, Basset, FH, Diagnosis and treatment of the plica syndrome of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg 1980; 62A:221. ![]()

141. Blackburn, TA, Eiland, G, Bandy, WD, et al, An introduction to the plica. J Orthop Sp Phys Ther 1982; 4:85–87. ![]()

142. Vaughan-Lane, T, Dandy, DJ, The synovial shelf syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg 1982; 64B:475–476. ![]()

143. Platel, D, Plica as a cause of anterior knee pain. Orthop Clin North Am 1986; 17:273–277. ![]()

144. Iino, S. Normal arthroscopic findings of the knee joint in adult cadavers. J Jpn Orthop Assoc. 1939; 14:467–523.

145. He, R, Yang, L, Guo, L, Painful locking of the knee due to bucket handle tear of mediopatellar plica. Chin J Traumatol. 2011;14(2):117–119. ![]()

146. Broom, HJ, Fulkerson, JP, The plica syndrome: a new perspective. Orthop Clin North Am 1986; 17:279–281. ![]()

147. Johnson, DP, Eastwood, DM, Witherow, PJ, Symptomatic synovial plicae of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg 1993; 75A:1485–1495. ![]()

148. Dupont, JY, Synovial plicae of the knee. Controversies and review. Clin Sports Med. 1997;16(1):87–122. ![]()

149. Rovere, GD, Adair, D, Medial synovial shelf plica syndrome: treatment by intraplical steroid injection. Am J Sports Med 1985; 13:383–386. ![]()

150. Amatuzzi, MM, Fazzi, A, Varella, MH, Pathologic synovial plica of the knee. Results of conservative treatment. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18(5):466–469. ![]()

151. Camanho, GL, Treatment of pathological synovial plicae of the knee. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2010;65(3):247–250. ![]()

152. Calvo, RD, Holden, SC, Sterling, JC, et al. Managing plica syndrome of the knee. Phys Sportsmed. 1990; 18:64–74.

153. Sakakibara, JO, Watanabe, M. Arthroscopy study on Iino’s band. J Jpn Orthop Assoc. 1976; 50:513–522.

154. Lee, JK, Yao, L, Tibial collateral ligament bursa: MR imaging. Radiology. 1991;178(3):855–857. ![]()

155. Kerlan, R, Glousman, R, Tibial collateral ligament bursitis. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16(4):344–346. ![]()

156. Schuldt, DR, Wolfe, RD, Clinical and arthrographic findings in meniscal cysts. Radiology 1980; 134:49–52. ![]()

157. Rothstein, CP, Laorr, A, Helms, CA, Tirman, PF, Semimembranosus-tibial collateral ligament bursitis: MR imaging findings. Am J Roentgenol. 1996;166(4):875–877. ![]()

158. Ombregt, L, Bursitis ter hoogte van het ligamentum collaterale mediale van de knie. Cyriax Info 1989; 2:5–6. ![]()

159. Ho, G, Tice, AD, Comparison of nonseptic and septic bursitis. Arch Intern Med 1979; 139:1269–1273. ![]()

160. Quayle, JB, Robinson, MP, An operation for chronic prepatellar bursitis. J Bone Joint Surg 1976; 58B:504–506. ![]()

161. Noble, CA, Iliotibial band friction syndrome in runners. Am J Sports Med 1980; 4:232–234. ![]()

162. Demeyere, N, De Maeseneer, M, Van Roy, P, et al, Imaging of semimembranosus bursitis: MR findings in three patients and anatomical study. JBR-BTR. 2003;86(6):332–334. ![]()

163. Reilly, JP, Nicholas, JA, The chronically inflamed bursa. Clin Sports Med 1987; 6:345–370. ![]()

164. Rennie, WJ, Saifuddin, A, Pes anserine bursitis: incidence in symptomatic knees and clinical presentation. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34(7):395–398. ![]()

165. Larsson, LG, Baun, J, The syndrome of anserina bursitis: an overlooked diagnosis. Arthritis Rheum 1985; 28:1062–1065. ![]()

166. Massari, L, Faccini, R, Lupi, L, Bighi, S, Diagnosis and treatment of popliteal cysts. Chir Organi Mov. 1990;75(3):245–252. ![]()