Disorders of the inert structures

Limited range of movement

Capsular pattern

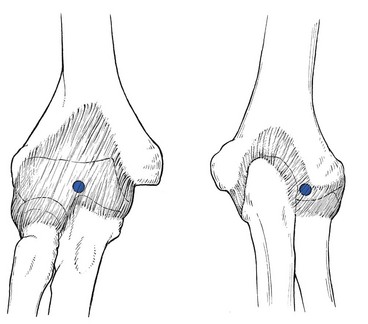

The capsular pattern at the elbow is characterized by limitation of flexion and extension (Fig. 18.1), flexion usually being more limited than extension, although equal limitation of both movements does occur. Rotations remain full and painless except in advanced arthritis, in which they can be painful at the end of the range.

The following conditions are the most common.

Traumatic arthritis

On palpation, some swelling may be detected. If the swelling came on immediately after an accident, it is probably caused by blood and this should be aspirated at once. If not, the effusion is secondary and disappears as soon as the arthritis subsides. Also, a positive fat pad sign on a lateral radiograph – a response to distension of the joint capsule – is indicative of intra-articular fluid.1,2

There are two situations that are worthy of attention.

Fracture of the olecranon

The olecranon lies superficially and is therefore very vulnerable. Injury to the elbow, and especially a fall on a bent elbow, may result in fracture of the olecranon. It is, of course, tender to the touch and marked articular signs are found on examination: warmth, swelling and limitation of passive movement in the capsular pattern.3,4 Resisted movements are also positive in that isometric extension, an action of the triceps muscle, is painful and weak (see also p. 453). Radiography confirms the fracture and its type: it is mostly displaced but stable, and then requires surgery. When it is not displaced, immobilization suffices.5

Fracture of the head of the radius

Radial head fractures account for about 30% of all elbow fractures and mostly occur as a result of falling on to an outstretched hand.6 They are most common in females.7

Treatment options for radial head fractures include conservative treatment, excision, open reduction–internal fixation, and arthroplasty, all depending on the type of fracture and the degree of displacement.8,9

Treatment

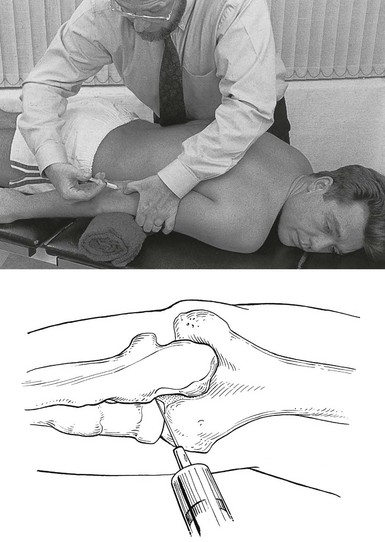

Technique: intra-articular injection![]()

The patient lies prone on a couch with a small pillow under the elbow. The arm is held by the side with the forearm fully supinated. In this position the joint lines between humerus and radius and the radial side of the olecranon are both easily felt. A 2 mL syringe is filled with triamcinolone acetonide 10 mg/mL and a 2 cm thin needle is fitted. The needle is inserted at the joint line and aimed slightly obliquely under the olecranon (Fig. 18.2).

Fig 18.2 Intra-articular injection.

Another valuable treatment is rest in flexion. It can be used in those patients who cannot tolerate an injection. As soon as the patient is seen, the elbow is immobilized in as much flexion as possible by means of a collar-and-cuff bandage. Every day the elbow is flexed more, until full movement can be achieved; thereafter it is held in this position for 2 weeks. The elbow is then rested in slightly less flexion. Three days later the joint is re-examined and, if the range of flexion is still full, the forearm is allowed to extend a little further. Some 6 weeks later, the patient reaches the stage in which the arm can be worn in a sling. After 2 or 3 months, movements of the elbow should be full and painless. Another static progressive splinting method by means of a turnbuckle splint has proved to be useful in the treatment of long-standing post-traumatic stiffness of the elbow.10,11

Arthrosis

This condition may come on spontaneously in late middle age12 and is often bilateral. It may also occur as the result of a fracture or dislocation.13 Intra-articular distal humerus fractures, for example, are most often associated with the development of degenerative joint disease over time.14 Repeated minor injuries15,16 or a loose body in the joint may also account for early arthritic changes.17

The patient, most often a male,18 complains that, after he uses his elbow excessively, the joint aches slightly. He may also find the inability to fully straighten the arm inconvenient.

The differential diagnosis is neuropathic arthropathy,19 which presents with gross painless limitation of movement in the capsular pattern.

Monoarticular steroid-sensitive arthritis

On radiography, decalcification and later erosion of cartilage may be visible.

Crystal synovitis

Gout (uric acid crystals) and pseudogout (calcium pyrophosphate crystals) seldom affect the elbow joint during a first attack (in only 4.5% of gout cases)20 but more frequently cause acute olecranon bursitis.21 As disease develops, polyarticular attacks may occur, in which case the elbow joint is affected in 30% of cases.

The sudden unprovoked onset and the shiny red appearance of the joint are characteristic.

The following diagnostic criteria may be useful in gout. When uric acid crystals are found in the synovial fluid during microscopic, chemical or histological examination, or tophi are seen on the ears, the diagnosis is certain, as it also is when two of the following four criteria are present: history of a typical attack of gout at the big toe; history of two typical attacks of gout at another joint; clinical picture of tophus; remission within 48 hours of the acute attack after the administration of colchicine or phenylbutazone.22

Haemarthrosis

Haemarthrosis may occur after injury to the joint, especially an intra-articular fracture or a direct contusion of the joint capsule, or, less commonly, in haemophilic patients. Bleeding into the joint leads to gross swelling and a marked capsular pattern.23 Aspiration must be carried out immediately to avoid destruction of cartilage.

Rheumatoid-type arthritis

Polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis may affect the elbow joint. Apart from the gross swelling, rapidly ensuing limitation of extension is typical.24 The elbow is also one of the sites of predilection, together with the knee and shoulder, for chondromatosis. Pigmented villonodular synovitis occurs most commonly at the knee, followed by elbow and ankle.25

In these and the other rheumatoid-type arthritides, systemic medication is required, and sometimes even a surgical approach. Good results have been reported with total elbow arthroplasty.26–33

Septic arthritis

A bacterial infection of the elbow joint is always very serious. It may not only lead to total destruction of the joint but may also be life-threatening.34

It can be the result of an open injury to the joint (e.g. open fracture), penetration of a foreign body (e.g. rose or bramble thorns during gardening or fruit picking) or direct inoculation of a bacterium during intra-articular injection, especially injection of a steroid suspension. It can also be caused by haematogenous dissemination from focal infections: dental abscess, cystitis, urethritis, skin infections. These causes are very dependent on the patient’s resistance to infections: patients with diabetes, renal failure or a deficient immune system (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis) are more likely to suffer from haematogenous dissemination followed by a septic arthritis.35–37

Treatment consists of systemic antibiotic therapy and daily local aspiration38 and drainage by arthroscopy.39

Tuberculous arthritis

Elbow tuberculosis is a rare disease which accounts for 1–3% of all cases of osteoarticular tuberculosis.40 The diagnosis is very difficult to make because of the insidious onset with mild and non-specific local or systemic symptoms. The radiological findings are also non-specific in the early stage. Tuberculosis of the elbow is therefore easily misdiagnosed as degenerative arthritis or rheumatoid arthritis.41 Several months after the onset of symptoms, there is pain at night, and examination reveals a gross capsular pattern and a spastic end-feel. The radiograph reveals periarticular osteopenia, bone erosion and joint space narrowing.42 On haematological testing, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) are elevated.43

The gold standard for the diagnosis of tuberculous arthritis is identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis either directly or after culture of the synovial fluid.44

Non-capsular pattern

Limitation of flexion or extension in isolation

Loose body in the joint

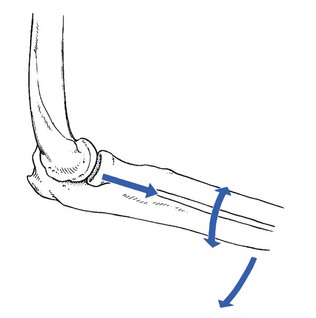

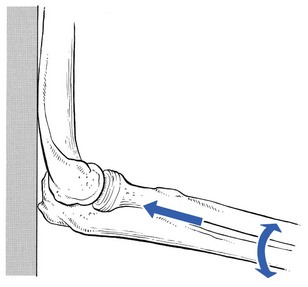

A loose body in the elbow joint is not uncommon and may hinder normal movements. It prevents the joint either from moving into full flexion, leaving extension free (Fig. 18.3), or from moving into full extension, leaving flexion free (Fig. 18.4). It then changes the hard end-feel of extension into a rather soft one.

In adolescence

A loose body is a common cause of elbow trouble in adolescents and is the only non-traumatic cause of arthrosis encountered in a young person. The condition does not occur before the age of 14 and usually results from osteochondritis dissecans, mostly on the humeral capitellum,45,46 or an intra-articular chip fracture, conditions that may lead to exfoliation of one or more fragments of bone covered by articular cartilage.47 Osteochondritis dissecans is not uncommon in young female gymnasts with hyperextension and valgus of the elbow.48–50 It also affects young pitchers or athletes involved in high-demand, repetitive overhead activities.51,52

Diagnosis can be confirmed by anteroposterior radiography performed with the elbow in 45° of flexion,53 because in this position the X-ray beam is almost parallel to the gap between the fragment and the underlying capitellar bone. Recently, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been suggested for assessing osteochondritis dissecans,54 and sonography also seems to be effective.55,56

If the patient is seen during an attack, manipulative reduction can be carried out. However, arthroscopic57,58 or surgical59 removal of the loose piece(s) should always be advised for the following reasons: as the loose body has an osseous nucleus and still lies within its nutrient synovial fluid, it may grow and the condition may worsen at each attack. It is also important to realize that the loose body is considerably larger than it may seem on a radiograph, as it is covered with radiotranslucent cartilage. If surgery is not performed, loose bodies may finally cause gross arthrosis.60 Limitation of extension may considerably hinder activities and should therefore be prevented.

In a normal joint in adulthood

A very clear non-capsular pattern is found with limitation of either flexion or extension, depending on the position of the fragment. If the loose body lies in the triangle formed by the humeral capitellum, the head of the radius and the base of the coronoid process of the ulna, extension is slightly limited, while flexion remains full and painless. The end-feel on passive extension is soft. When the loose piece of cartilage lies anteriorly, flexion is quite limited, the fragment catching between the anterior aspect of the humerus and the tip of the coronoid process (Fig. 18.5).

A loose body that limits extension can usually be reduced. Manipulation under strong traction shifts the loose piece of cartilage to a position at the back of the joint. It then no longer blocks movement, which becomes normal again. The manipulation can be repeated each time derangement occurs. Nothing else should be done, unless recurrence is very frequent, in which case removal during arthroscopy would be a possibility.61,62

A loose body that limits flexion cannot be reduced by manipulation, but limitation of flexion, unless gross, is not a major concern. The alternatives in this case are: arthroscopic or surgical removal or nothing, depending on the patient’s age, preference and functional disablement.63 If nothing is done, there is some danger that the loose body will become embedded and be responsible for a permanent limitation of flexion.

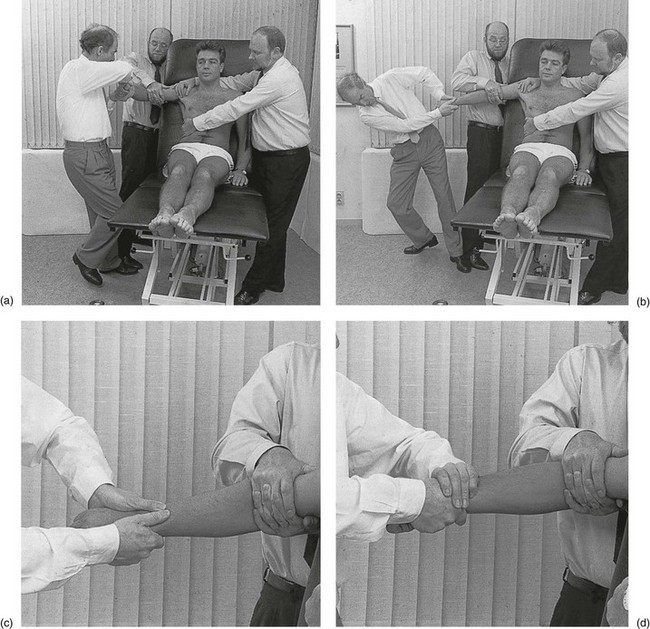

Technique: manipulative reduction of a loose body

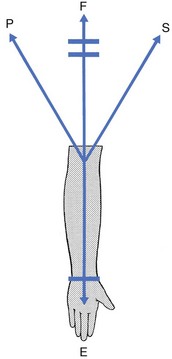

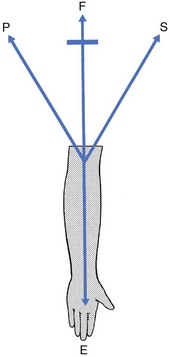

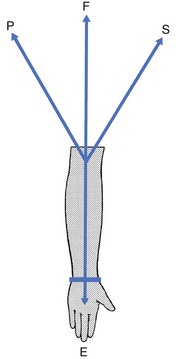

In this manipulation different elements are incorporated: traction, movement from flexion towards extension, and rotation movements, either pronation![]() or supination

or supination![]() (Figs 18.6 and 18.7).

(Figs 18.6 and 18.7).

The manipulator puts the contralateral foot against that of the first assistant vertically below the patient’s elbow. This is the fixed point around which pivoting takes place as the elbow is moved from flexion towards extension. The patient’s lower forearm just proximal to the wrist is then grasped with both hands. The position of the hands is slightly different, depending on the chosen rotation (see Fig. 18.6). The use of the manipulator’s body weight is then able to exert the traction required to distract the joint. Pivoting on the foot, movement is gradually made from flexion towards extension while the patient’s forearm is moved in either pronation or supination through the full range. At the last moment as extension is approached, the manipulator’s trunk is side-flexed away from the patient to exert maximal traction. Extension movement is not performed beyond the degree of limitation; if this should happen, it would, of course, result in traumatic arthritis of the joint.

In an arthrotic joint in middle or old age

Manipulative treatment can be performed during the attacks, although it is not strictly necessary because the condition subsides spontaneously. It is enough to explain the mechanism to the patient. Alternatively, arthroscopic removal can be considered.64,65

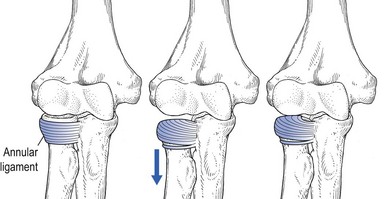

Acute limitation of supination and extension in children

Radial head subluxation also known as pulled elbow, dislocated elbow or nursemaid’s elbow, is one of the most common upper extremity injuries in young children under 8 years of age. The injury usually occurs when forceful longitudinal traction is applied to an extended and pronated arm,66 as in lifting a child by the forearm or pulling the forearm of a resisting child. This manœuvre is immediately followed by pain and limitation of movement; the elbow is held flexed at about 90° and in pronation – hence the French name, ‘la pronation douloureuse’.67

A ‘pulled elbow’ is actually a displacement of the annular ligament between the capitellum of the distal humerus and the radial head. The latter is pulled distally through the annular ligament, which becomes displaced from its normal position covering the radial head, into the radiohumeral joint (Fig. 18.8).68

The subsequent disturbance of the lower radioulnar joint is responsible for the limitation of supination. Ultrasonography of the radiohumeral joint shows that the distance between the radial head and the capitellum is increased, probably because of the interposition of the annular ligament into the radiohumeral joint.69 A radiograph of the wrist shows a distal shift of the radius compared to the ulna, which is restored after manipulation.70

Reduction is easy. Sometimes spontaneous reduction occurs just by bringing the forearm into supination and flexion, as in examining for passive flexion of the elbow.71,72 When this does not happen, manipulation is performed.73

Technique: reduction of a ‘pulled elbow’

The child is asked to stand against a wall. The upper arm is abducted and the elbow flexed to a right angle. The manipulator grasps the child’s lower forearm with the ipsilateral hand and pushes the radius upwards towards the humerus by pressing the elbow against the wall. In the mean time, the forearm is rapidly rotated to and fro to the end of the range in either direction (Fig. 18.9). Suddenly, on full supination, the radial head reduces with a palpable click.

Limitation of pronation

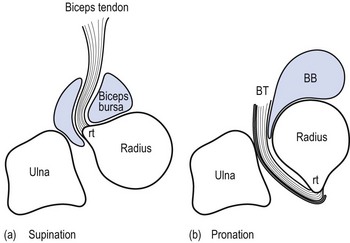

The bicipitoradial bursa is located at the insertion of the distal biceps tendon. In supination it surrounds the biceps tendon. In pronation, the radial tuberosity rotates posteriorly, which compresses the bicipitoradial bursa between the biceps tendon and the radial cortex (Fig. 18.10).74

When inflamed, the bursa may enlarge and produce symptoms and signs.75 Classically, patients with cubital bursitis present with a mass in the cubital fossa and pain at the anterior aspect of the elbow,76,77 together with symptoms and signs resulting from compression of one of the branches of the radial nerve.78 In our experience, most cases of bicipital bursitis present only with cubital pain and a painful limitation of the pronation with a soft end-feel. The condition can be treated with infiltration of 20 mg of triamcinolone suspension. The same technique is used as for bicipital tendinitis but the infiltration is done somewhat more proximally between the tendon and the bone of the radius (see p. 299).

Full range of movement

Pain on full passive pronation

This sign usually accompanies the primary signs of a bicipital tendinitis (see below) and indicates that the lesion lies at its attachment to the radial tuberosity. In the unusual circumstances in which bicipital tendinitis is absent, pain on passive pronation should be regarded as a bicipitoradial bursitis.79

Ligamentous lesions

Ulnar collateral ligament

Partial or total rupture of the ulnar collateral ligament resulting from overhand throwing has been described extensively in athletes.80–82 Most affected individuals are high-level baseball pitchers, tennis players and javelin throwers. This condition is often complicated by irritation of the ulnar nerve.83 Usually the lesion results from chronic overuse of the elbow leading to ligamentous insufficiency, even in the absence of a singular catastrophic episode of ligament failure.84

Commonly athletes note a history of recurrent elbow pain after or during throwing, without a specific injury.85 On physical examination there may be a capsular pattern if the lesion is acute. In chronic lesions, the standard clinical examination will be entirely negative and the joint must be tested for valgus instability. For this purpose the moving valgus stress test has been found to be extremely useful, given its high degree of sensitivity and specificity.86 The patient lies supine with the arm abducted and externally rotated. The elbow is in neutral rotation.87 The examiner then applies and maintains a constant moderate valgus torque to the fully flexed elbow while gradually extending it. The test is positive if the medial elbow pain is reproduced within the arc between 120 and 70°.88

Surgical intervention may be necessary when conservative treatment fails and in a patient who wants to return to highly competitive sports.89,90

In young throwing athletes, repetitive high valgus stress and pull by the common flexor tendon may result in subtle stress fracture of the medial epicondyle epiphysis. It manifests with pain at the medial aspect of the elbow and diminished throwing distance and effectiveness. The medial epicondyle is very tender to the touch and a slight capsular pattern may be found. This lesion is called ‘medial epicondylar stress lesion’ or ‘little league elbow’.91–93

Radial collateral ligament

A lesion of the radial collateral ligament occurs rarely as the result of repetitive isolated varus stress but mostly after complete elbow dislocation.94 It may lead to posterolateral rotatory instability, giving rise to symptoms such as clicking, snapping and locking.63 Tests, such as the lateral pivot shift or posterolateral rotatory drawer test, have been devised for confirming the diagnosis.95 In recurrent problems, surgical reconstruction or repair seems to give good results.96

Bursitis

Olecranon bursitis

Because the bursa is superficial it is very vulnerable. The lesion can be provoked by repetitive direct pressure – for example, leaning the elbow on a table – or by falling heavily on to the bent elbow. It is often associated with occupational or sports trauma, or systemic conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis, gout, tuberculosis and rheumatic diseases (e.g. chondrocalcinosis, xanthomatosis).97,98

Differential diagnosis must be made between a traumatic bursitis and an infected bursa. Septic bursitis presents with heat and redness of the skin and pain on resisted extension of the elbow.97,98 Analysis of the bursal fluid obtained through aspiration may be helpful.99

Sometimes aspiration alone will not prevent the fluid from reaccumulating because of continued movements of the elbow. Adding non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs will then hasten symptomatic improvement. Arthroscopic excision can be used when conservative treatment fails.100 Septic bursitis should be treated immediately with antibiotic therapy and/or drainage. Sometimes, in the most stubborn cases, surgical excision is necessary.101

References

1. Siegel, MJ, Elbow fat pads with new signs and extended differential diagnosis. Radiology. 1977;124(3):659–665. ![]()

2. Goswami, GK, The fat pad sign. Radiology. 2002;222(2):419–420. ![]()

3. Docherty, MA, Schwab, RA, Ma, OJ, Can elbow extension be used as a test of clinically significant injury? South Med J 2002; 95:539–541. ![]()

4. Appelboam, A, Reuben, AD, Benger, JR, et al, Elbow extension test to rule out elbow fracture: multicentre, prospective validation and observational study of diagnostic accuracy in adults and children. BMJ 2008; 337:a2428. ![]()

5. Cabanela, ME, Morrey, BF. Fractures of the olecranon. In: Morrey BF, ed. The Elbow and its Disorders. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:365–379.

6. Carroll, RM, Osgood, G, Blaine, TA. Radial head fractures: repair, excise, or replace? Curr Opin Orthop. 2002; 13:315–322.

7. Morrey, BF. Radial head fracture. In: Morrey BF, ed. The Elbow and its Disorders. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:341–364.

8. Geel, GW, Palmer, AK, Radial head fractures and their effect on the distal radio-ulnar joint. Rationale for treatment. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1992; 275:79–84. ![]()

9. Gupta, A, Kamineni, S, Patten, DK, Skourat, R. Displaced operable radial head fractures. Functional outcome correlations. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2008; 34:378–384.

10. Gelinas, JJ, Faber, KJ, Patterson, SD, King, GJ, The effectiveness of turnbuckle splinting for elbow contractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82(1):74–78. ![]()

11. Doornberg, JN, Ring, D, Jupiter, JB, Static progressive splinting for posttraumatic elbow stiffness. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(6):400–404. ![]()

12. Doherty, M, Preston, B, Primary osteoarthritis of the elbow. Ann Rheum Dis 1989; 48:743. ![]()

13. Smith, FM. The Elbow, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1972.

14. O’Driscoll, SW, Elbow arthritis: treatment options. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1993;1(2):106–116. ![]()

15. Sakakibara, H, Suzuki, H, Momoi, Y, Yamada, S, Elbow joint disorders in relation to vibration exposure and age in stone quarry workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1993;65(1):9–12. ![]()

16. Hellmann, DB, Helms, CA, Genant, HK, Chronic repetitive trauma: a cause of atypical degenerative joint disease. Skeletal Radiol 1983; 10:236. ![]()

17. Morrey, BF, Primary degenerative arthritis of the elbow. Treatment by ulnohumeral arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74B(3):409–413. ![]()

18. Minami, M, Kato, S, Kashiwagi, D. Outerbridge – Kashiwagi’s method for arthroplasty of osteoarthritis of the elbow: 44 elbows followed for 8–16 years. J Orthop Sci. 1996; 1:11.

19. Morrey, BF. Primary degenerative arthritis of the elbow: ulnohumeral arthroplasty. In: Morrey BF, ed. The Elbow and its Disorders. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:799.

20. Dieppe, PA, Calvent, P. Crystals and Joint Disease. London: Chapman & Hall; 1982.

21. Tompkins, RB. Nonrheumatoid inflammatory arthritis. In: Morrey BF, ed. The Elbow and its Disorders. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:793–794.

22. Wallace, SL, Robinson, H, Masi, AT, et al, Preliminary criteria for the classification of the acute arthritis of primary gout. Arthritis Rheum 1977; 20:895. ![]()

23. O’Driscoll, SW, Morrey, BF, An, KN, Intra-articular pressuring capacity of the elbow. Arthroscopy 1990; 6:100. ![]()

24. Luthra, HS. Rheumatoid arthritis. In: Morrey BF, ed. The Elbow and its Disorders. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:781–783.

25. Cloud, SR. Intraarticular thiotepa held effective in pigmented villonodular synovitis. American Rheumatic Association Western Region Meeting, Wellcome Trend Rheum. 3(2), 1981.

26. Maloney, WJ, Schurman, DJ, Cast immobilization after total elbow arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1989; 245:117. ![]()

27. Ewald, FC, Scheinberg, RD, Poss, R, et al, Capitello-condylar total elbow arthroplasty: two to five year follow-up in rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg 1980; 62A:1259. ![]()

28. Sjoden, G, Blomgren, G, The Souter–Strathclyde elbow replacement in rheumatoid arthritis. 13 patients followed for 5 (1–9) years. Acta Orthop Scand. 1992;63(3):315–317. ![]()

29. Morrey, BF, Adams, RA, Semiconstrained arthroplasty for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74A(4):479–490. ![]()

30. Ruth, JT, Wilde, AH, Capitellocondylar total elbow replacement. A long-term follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74A(1):95–100. ![]()

31. Brady, O, Quinlan, W, The Guildford elbow. J Hand Surg. 1993;18B(3):389–393. ![]()

32. Morrey, BF, Adams, RA, Semiconstrained elbow replacement for distal humeral nonunion. J Bone Joint Surg 1992; 77B:67. ![]()

33. Schneeberger, AG, Adams, RA, Morrey, BF, Semiconstrained total elbow replacement for the treatment of post-traumatic osteoarthrosis. J Bone Joint Surg 1997; 79A:1211. ![]()

34. Veys, EM, Mielants, H, Verbruggen, G. Reumatologie. Ghent: Omega; 1985.

35. Meijers, KA, Dijkmans, BA, Hermans, J, et al, Non-gonococcal infectious arthritis: a retrospective study. J Infection 1987; 14:13–20. ![]()

36. Goldenberg, DL, Reed, JI, Bacterial arthritis. NEJM 1985; 312:764. ![]()

37. Ho, G, Bacterial arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 1992; 4:509. ![]()

38. Mielants, H, Dhondt, E, Goethals, L, et al, Long-term functional results of non-surgical treatment of common bacterial infections of joints. Scand J Rheumatol 1981; 11:101. ![]()

39. Butters, KP, Morrey, BF. Septic arthritis. In: Morrey BF, ed. The Elbow and its Disorders. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:811–813.

40. Rahman, MS, Brar, R, Konchwalla, A, Sala, MJ, Pain in the elbow: a rare presentation of skeletal tuberculosis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(1):e19–e21. ![]()

41. Chen, WS, Wang, CJ, Eng, HL, Tuberculous arthritis of the elbow. Int Orthop 1997; 21:367–370. ![]()

42. Hunfeld, KP, Rittmeister, M, Wichelhaus, TA, et al, Two cases of chronic arthritis of the forearm due to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1998; 17:344–348. ![]()

43. Chen, WS, Wang, CJ, Eng, HL, Tuberculous arthritis of the elbow. Int Orthop 1997; 21:367–370. ![]()

44. Hunfeld, KP, Rittmeister, M, Wichelhaus, TA, et al, Two cases of chronic arthritis of the forearm due to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1998; 17:344–348. ![]()

45. McManama, GB, Micheli, LT, Berry, MV, et al, The surgical treatment of osteochondritis of the capitellum. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13(1):11. ![]()

46. Angelo, RL, Arthroscopy. Advances in elbow arthroscopy. Orthopedics. 1993;16(9):1037–1046. ![]()

47. Lindholm, TS, Osterman, K, Vankka, E, Osteochondritis dissecans of the elbow, ankle and hip: a comparative survey. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1980; 148:245. ![]()

48. Singer, R, Roy, S, Osteochondrosis of the humeral capitulum. Am J Sports Med. 1984;12(5):351. ![]()

49. Jackson, DW, Silvino, N, Reiman, P, Osteochondritis in the female gymnast’s elbow. Arthroscopy 1989; 5:129. ![]()

50. Maffulli, N, Chan, D, Aldridge, MJ, Derangement of the articular surfaces of the elbow in young gymnasts. J Pediatr Orthop. 1992;12(3):344–350. ![]()

51. Takahara, M, Mura, N, Sasaki, J, Harada, M, Ogino, T, Classification, treatment, and outcome of osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral capitellum. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(6):1205–1214. ![]()

52. Baker, CL, 3rd., Romeo, AA, Baker, CL, Jr., Osteochondritis dissecans of the capitellum. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(9):1917–1928. ![]()

53. Ruchelsman, DE, Hall, MP, Youm, T, Osteochondritis dissecans of the capitellum: current concepts. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(9):557–567. ![]()

54. Kijowski, R, De Smet, AA, MRI findings of osteochondritis dissecans of the capitellum with surgical correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185(6):1453–1459. ![]()

55. Frankel, DA, Bargiela, A, Bouffard, JA, et al, Synovial joints: evaluation of intraarticular bodies with US. Radiology 1998; 206:41–44 [Abstract/Free Full Text]. ![]()

56. Takahara, M, Ogino, T, Tsuchida, H, et al, Sonographic assessment of osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral capitellum. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174(2):411–415. ![]()

57. Andrews, JR, Carson, WG, Arthroscopy of the elbow. Arthroscopy 1985; 1:97. ![]()

58. Boe, A, Molster, A, Albueartroskopi. Tidsskr Nor Lægeforen. 1992;112(4):493–494. ![]()

59. Takahara, M, Mura, N, Sasaki, J, et al, Classification, treatment, and outcome of osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral capitellum. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(6):1205–1214. ![]()

60. Takahara, M, Ogino, T, Takagi, M, et al, Natural progression of osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral capitellum: initial observations. Radiology. 2000;216(1):207–212. ![]()

61. O’Driscoll, SW, Morrey, BF, Elbow arthroscopy for loose bodies. Orthopedics. 1992;15(7):855–859. ![]()

62. O’Driscoll, SW, Morrey, BF, Arthroscopy of the elbow. Diagnostic and therapeutic benefits and hazards. J Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74A(1):84–94. ![]()

63. O’Driscoll, SW, Morrey, BF, Korinek, S, An, KN, Elbow subluxation and dislocation: a spectrum of instability. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1992; 280:186–197. ![]()

64. Clasper, JC, Carr, AJ, Arthroscopy of the elbow for loose bodies. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2001;83(1):34–36. ![]()

65. Ozbaydar, MU, Tonbul, M, Altan, E, Yalaman, O, Arthroscopic treatment of symptomatic loose bodies in osteoarthritic elbows. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2006;40(5):371–376. ![]()

66. Illingworth, C, Pulled elbow. BMJ 1975; i:672. ![]()

67. Choung, W, Heinrich, SD, Acute annular ligament interposition into the radiocapitellar joint in children (nursemaid’s elbow). J Pediatr Orthop 1995; 15:454. ![]()

68. Tachdjian, MO. Clinical Pediatric Orthopedics. Stamford: Appleton & Lange; 1997.

69. Kosuwon, W, Mahaisavariya, B, Saengnipanthkul, S, et al, Ultrasonography of pulled elbow. J Bone Joint Surg 1993; 75B:421–422. ![]()

70. Mehara, AK, Bhan, S, A radiological sign in pulled elbows. Int Orthop. 1995;19(3):174–175. ![]()

71. Triantafyllou, SJ, Wilson, SC, Rychak, JS, Irreducible ‘pulled elbow’ in a child. A case report. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1992; 284:153–155. ![]()

72. Letts, RM. Dislocations of the child’s elbow: pulled elbow syndrome. In: Morrey BF, ed. The Elbow and its Disorders. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:273–276.

73. Bek, D, Yildiz, C, Köse, O, et al, Pronation versus supination maneuvers for the reduction of ‘pulled elbow’: a randomized clinical trial. Eur J Emerg Med. 2009;16(3):135–138. ![]()

74. Skaf, AY, Boutin, RD, Dantas, RW, et al, Bicipitoradial bursitis: MR imaging findings in eight patients and anatomic data from contrast material opacification of bursae followed by routine radiography and MR imaging in cadavers. Radiology. 1999;212(1):111–116. ![]()

75. Liessi, G, Cesari, S, Spaliviero, B, et al, The US, CT and MR findings of cubital bursitis: a report of five cases. Skeletal Radiol 1996; 25:471–475. ![]()

76. Bourne, M, Morrey, BF, Partial rupture of the distal biceps tendon. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1991; 271:143. ![]()

77. Karanjia, ND, Stiles, PJ, Cubital bursitis. J Bone Joint Surg 1988; 70B:832. ![]()

78. Bak, B, Bicipitoradial bursitis. Ugeskr Laeger. 2008;170(40):3123–3124. ![]()

79. Karanjia, ND, Stiles, PJ, Cubital bursitis. J Bone Joint Surg 1988; 70B:832. ![]()

80. Jobe, FW, Stark, H, Lombardo, SJ, Reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament in athletes. J Bone Joint Surg 1986; 68A:1158. ![]()

81. Pappas, AM, Zawacki, RM, Sullivan, TJ, Biomechanics of baseball pitching: a preliminary report. Am J Sports Med 1985; 13:216. ![]()

82. Jobe, FW, Nuber, G, Throwing injuries of the elbow. Clin Sports Med 1985; 5:521. ![]()

83. Conway, JE, Jobe, FW, Glousman, RE, Pink, M, Medial instability of the elbow in throwing athletes: surgical treatment by ulnar collateral ligament repair or reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg 1992; 74A:67. ![]()

84. Cain, EL, Dugas, JR, Wolf, RS, et al, Elbow injuries in throwing athletes: a current concepts review. Am J Sports Med 2003; 31:621–635. ![]()

85. Hyman, J, Breazeale, NM, Altchek, DW, Valgus instability of the elbow in athletes. Clin Sports Med 2001; 2025–2045. ![]()

86. O’Driscoll, SW, Lawton, RL, Smith, AM, The ‘moving valgus stress test’ for medial collateral ligament tears of the elbow. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(2):231–239. ![]()

87. Safran, MR, McGarry, MH, Shin, S, et al, Effects of elbow flexion and forearm rotation on valgus laxity of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87:2065–2074. ![]()

88. Safran, MR, Ulnar collateral ligament injury in the overhead athlete: diagnosis and treatment. Clin Sports Med. 2004;23(4):643–663. ![]()

89. Jobe, FW, Elattrache, NS. Diagnosis and treatment of ulnar collateral ligament injuries in athletes. In: Morrey BF, ed. The Elbow and its Disorders. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:549–555.

90. Dodson, CC, Thomas, A, Dines, JS, et al, Medial ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction of the elbow in throwing athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(12):1926–1932. ![]()

91. Blohm, D, Kaalund, S, Jakobsen, BW, ‘Little league elbow’ – acute traction apophysitis in an adolescent badminton player. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1999;9(4):245–247. ![]()

92. Bennett, JB, Mehlhoff, TL. Articular injuries in the athlete. In: Morrey BF, ed. The Elbow and its Disorders. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:565.

93. Wei, AS, Khana, S, Limpisvasti, O, et al, Clinical and magnetic resonance imaging findings associated with little league elbow. J Pediatr Orthop. 2010;30(7):715–719. ![]()

94. Freeman, BL. Recurrent dislocations. In: Crenshaw AH, ed. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics. 7th ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1987:2212.

95. O’Driscoll, SW, Bell, DF, Morrey, BF, Posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg 1991; 73A:440. ![]()

96. Nestor, B, O’Driscoll, SW, Morrey, BF. Surgical stabilization for lateral rotatory instability of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg. 74A(1235), 1992.

97. Canoso, JJ, Scheckman, PR, Septic subcutaneous bursitis, report of sixteen cases. J Rheumatol. 1979;6(1):96. ![]()

98. Ho, G, Jr., Tice, AD, Kaplan, SR, Septic bursitis in the prepatellar and olecranon bursae: an analysis of 25 cases. Ann Intern Med. 1978;89(1):21. ![]()

99. Stell, IM, Septic and non-septic olecranon bursitis in the accident and emergency department – an approach to management. J Accid Emerg Med. 1996;13(5):351–353. ![]()

100. Kerr, DR, Carpenter, CW, Arthroscopic resection of olecranon and prepatellar bursae. Arthroscopy. 1990;6(2):86. ![]()

101. Reilly, JP, Nicholas, JA, The chronically inflamed bursa. Clin Sports Med. 1987;6(2):112–114. ![]()