23 Disorders of the Hip and Lower Extremity

Congenital

Clubfoot

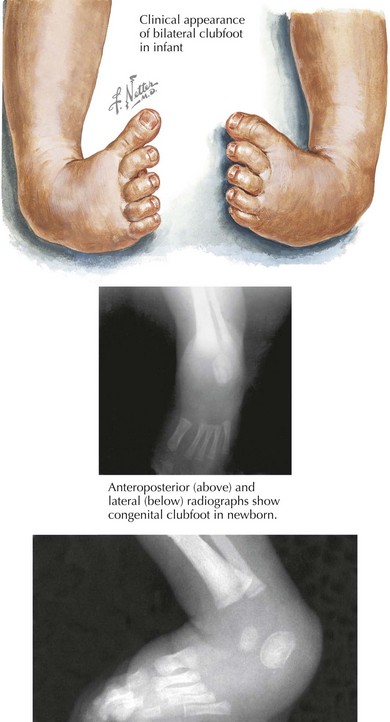

Clubfoot, or talipes equinovarus, affects one in 1000 live births and is often diagnosed in utero. The condition is characterized by a smaller foot on the affected side, rigidity to plantar flexion, adductus of the forefoot, and inward angulation of the hindfoot (Figure 23-1). Half of cases are bilateral. Although many cases are idiopathic, maternal smoking, certain ethnic backgrounds, and genes affecting both the musculoskeletal and nervous systems have been identified as risk factors. Some believe that disordered development of the talus in utero causes the disorder.

Developmental

In-toeing

Internal Tibial Torsion

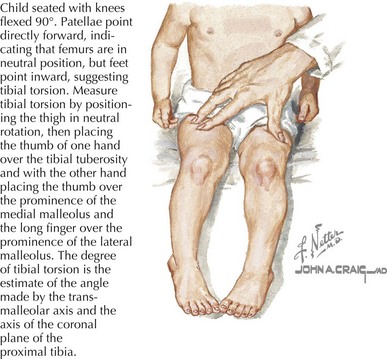

Internal tibial torsion is the most common cause of in-toeing and can be associated with metatarsus adductus. It is usually noted in toddlerhood when children begin to walk. It affects boys and girls equally and is bilateral in about two-thirds of cases. On examination, the knee remains in neutral position while the foot is medially rotated (Figure 23-2). Most cases self-resolve as children begin to walk independently, with normal alignment noted as early as 4 years or as late as 10 years of age.

Bowlegs

Rickets

Rickets is a correctible cause of bowlegs that can be differentiated from tibia vara by family history, radiographic stigmata, and laboratory assessment. Rickets is an anomaly of bone mineralization that develops gradually in growing children because of calcium, phosphate, or vitamin D deficiency or resistance. Bowing of the legs, flaring of metaphyses, and “rachitic rosary” deformity of the ribs may all be seen on physical examination or plain films. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends 400 IU of vitamin D supplementation for all infants receiving less than 1 L of formula daily to prevent rickets. Metabolic bowing usually resolves with metabolic control and rarely requires surgical correction. See Chapter 69 for a more complete discussion of rickets.

Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

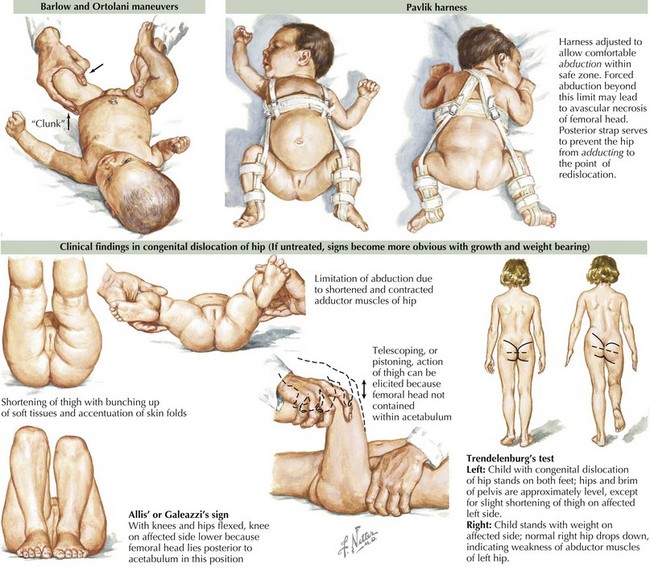

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) bears special mention because it must be diagnosed promptly and does not resolve without intervention. DDH is a rare disorder with high morbidity when the diagnosis is made after 6 months of age. It is characterized by an abnormal relationship between the hip socket, or acetabulum, and the femoral head. DDH represents a spectrum of disorders ranging from mild ligamentous laxity of the hip joint to a fully displaced femoral head. Diagnosis is made by physical examination of the neonate; finding a hip clunk on the Barlow or Ortolani maneuvers warrants immediate orthopedics referral. Whereas the Barlow test can identify a dislocatable hip, the Ortolani test attempts to reduce a dislocation (Figure 23-3). After the first few months of life, limitation or asymmetry of hip abduction is a more reliable examination finding.

Very mild abnormalities of the hip joint often resolve spontaneously in the first few months of life. When a true dislocation is diagnosed before 6 months of age, the Pavlik harness is the treatment of choice. It is a splint that prevents hip extension and adduction, which can be adjusted as the child grows (see Figure 23-3). Triple diapering or other measures to force the hip into place are no longer seen as effective treatment measures. Diagnosis after age 6 months usually requires surgical repair. When not diagnosed in infancy, parents or pediatricians may notice that the affected child has a waddling or Trendelenburg gait when beginning to walk (see Figure 23-3). DDH may be more difficult to detect in older children because they often have bilateral involvement and therefore may not have a markedly asymmetric gait. These children require an urgent orthopedic referral because they are at high risk for long-term morbidity.

Acquired

The majority of acquired disorders of the lower extremity are traumatic in origin. Common fractures of the lower extremity are discussed in Chapter 22, and injuries frequently encountered in young athletes are discussed in Chapter 25. Children who present with lower extremity pain or limp and have no history of trauma can be the cause of much anxiety to pediatric practitioners. The differential diagnosis for acquired limp in the child is vast and includes infectious, oncologic, rheumatologic, metabolic, and inflammatory processes. We focus here on several acquired processes not covered elsewhere in this textbook.

Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis

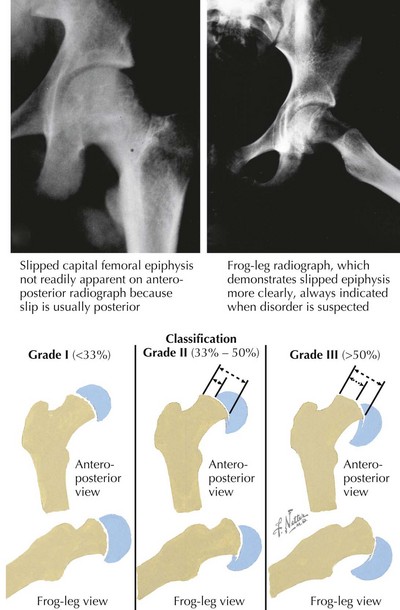

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) refers to an instability of the proximal femoral growth plate in which the femoral head slips posteriorly and inferiorly relative to the femoral neck (Figure 23-4). Although rare, SCFE is an extremely important diagnosis to make because prompt surgical repair is required, and a delay in diagnosis can lead to avascular necrosis. Patients with SCFE are typically obese children in their preadolescent and early adolescent years. A recent study found an incidence of 10.8 SCFE cases per 100,000 children. This incidence is higher in boys than girls and African Americans than whites. Obesity places increased force on the proximal femoral growth plate, putting children at risk for slippage.

Diagnosis is made on anteroposterior (AP) and frog-leg radiographs of the pelvis. The AP view can show widening of the physis and misalignment of the femoral capital epiphysis. On the AP view, the lack of intersection of a line drawn along the femoral neck (Klein’s line) and the femoral epiphysis can confirm the diagnosis. On the frog-leg view, the posterior portion of the femoral head becomes medial, making the slippage more apparent and giving a slipped “ice cream cone” appearance (see Figure 23-4). Patients found to have SCFE should be made non–weight bearing and need to see an orthopedist emergently. Treatment consists of internal fixation using a single cannulated screw, which prevents further slippage and provides symptom relief. There is a great deal of controversy surrounding the role of prophylactic fixation of the unaffected hip in unilateral SCFE.

Legg-Calvé-Perthes Disease

These patients usually have an insidious onset of mild pain worsened by activity that may refer to the thigh or knee. On examination, patients may have a Trendelenburg gait, pain, or decreased range of motion with internal rotation and abduction and even atrophy of the muscle groups in the thighs and buttocks. In advanced disease, radiographs can be helpful and may show fragmentation of the femoral head (Figure 23-5). In early cases, however, radiographic changes can be subtle or nonexistent. A significant concern for LCP may mandate further imaging such as a bone scan or MRI.

Transient Synovitis

Transient synovitis (TS) is characterized by inflammation of the hip synovium and is the most common cause of acute hip pain in young children. Children with TS are generally well appearing but have hip pain, a limp, or both. They often have low-grade fevers as well. TS typically presents at 3 to 8 years of age, and boys are affected twice as often as girls. It is often attributed to an infectious cause because many children have a history of a preceding upper respiratory infection. The principal concern with TS is distinguishing it from septic arthritis, which can result in significant morbidity if not promptly diagnosed and treated. To this end, inflammatory markers can be helpful. Children with high fevers or elevated inflammatory markers often require hip ultrasonography and aspiration of hip fluid if effusion is identified. The difference between TS and septic arthritis is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 88. TS is self-limited, but NSAIDs have been shown to shorten the duration of symptoms.

2000 Clinical practice guideline: early detection of developmental dysplasia of the hip. Committee on Quality Improvement, Subcommittee on Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip. American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2000;105(4 Pt 1):896-905.

Gholve PA, Cameron DB, Millis MB. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis update. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21(1):39-45.