103 Disorders of the Gastrointestinal System

Intestinal Obstruction

Clinical Presentation

Subtle differences in presentation can suggest the location of the obstruction along the alimentary tract (Table 103-1). These unique features are highlighted below as each disorder is discussed.

| Sign or Finding | Proximal or Distal | Specific Site (When Applicable) |

|---|---|---|

| Nonbilious vomiting | Proximal | Proximal to the ampulla of Vater |

| Bilious vomiting | Proximal or distal | Distal to the ampulla of Vater |

| Scaphoid abdomen | Proximal | Often preduodenal |

| Distended abdomen | Distal | |

| Maternal polyhydramnios | Proximal |

Esophageal Atresia

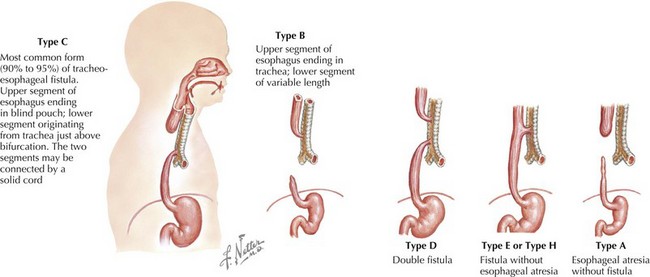

The esophagus can be obstructed in the form of esophageal atresia (EA), which is caused by a failure of separation of the esophagus from the trachea during normal development. Pure EA is rare and often coexists with tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF). A standard classification scheme describes the relationship between the atresia and the coexistent TEF (Figure 103-1). The most common combination is EA with distal TEF (type C). The most difficult to recognize and diagnose is “H-type,” which refers to isolated TEF without EA.

Pyloric Stenosis

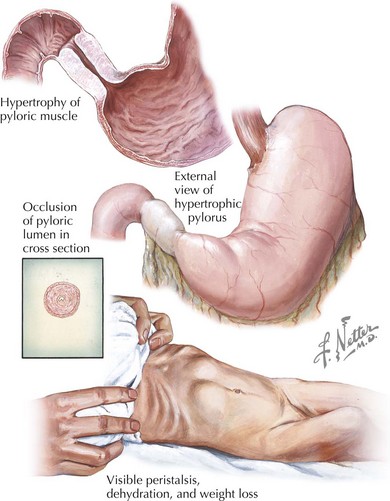

Obstruction at the level of the pylorus from congenital abnormalities, such as webs or membranes, is rare in the immediate neonatal period. However, approximately one in 500 infants will develop hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (HPS) during the first month of life (Figure 103-2). The classic presentation of HPS is a 3- to 4-week-old infant with persistent nonbilious projectile vomiting after each feed. Although found in male and female infants of all ethnicities, first-born male white infants seem to be disproportionately affected. Use of the antibiotic erythromycin in the neonatal period is a known risk factor as well. Infants with HPS appear irritable and hungry, and in some cases, a mass in the shape of an olive can be palpated in the right upper quadrant, representing the hypertrophic pyloric sphincter. Immediately after feeding, a reverse peristaltic wave may be seen just before vomiting. The abdomen may appear scaphoid before air and feeds are not able to pass beyond the level of the pylorus.

Imperforate Anus

Imperforate anus results from a failure of the normal development of the hindgut. The presence of imperforate anus should be apparent on physical examination and may be associated with other congenital anomalies (i.e., VACTERL [vertebral anomalies, anal atresia, cardiovascular anomalies, tracheoesophageal fistula, esophageal atresia, renal or radial anomalies, and limb defects] association; see Chapter 120).

Evaluation and Management

In all cases of suspected intestinal obstruction, evaluation should proceed quickly. After stabilizing the patient, confirmation of the presence of obstruction with abdominal radiography or other imagining modality and consultation with pediatric surgeons should ensue. Initial stabilization should include eliminating oral feeds, correcting any electrolyte or metabolic abnormalities, administering intravenous (IV) fluid boluses for unstable patients and starting maintenance fluids, and placement of a nasogastric (NG) or orogastric (OG) tube to decompress the abdomen. Blood cultures should also be sent and empiric antibiotic coverage for intestinal flora initiated. There are specific diagnostic options and management steps to consider based on the suspected obstruction syndrome, as discussed below. Finally, specific causes of intestinal obstruction may be components of genetic syndromes and should prompt complete evaluation to rule out associated conditions (Table 103-2).

Table 103-2 Site of Obstruction and Associated Genetic Syndromes

| Type of Obstruction | Genetic Association |

|---|---|

| Esophageal atresia | VACTERL |

| Duodenal atresia | Down syndrome |

| Colonic atresia | Eye, heart, and abdominal wall anomalies |

| Meconium ileus | Cystic fibrosis |

| Small left colon syndrome | Diabetic mother |

VACTERL, vertebral anomalies, anal atresia, cardiovascular anomalies, tracheoesophageal fistula, esophageal atresia, renal or radial anomalies, and limb defects.

Malrotation and Volvulus

When an infant presents with bilious emesis, an upper GI series must be performed emergently because the time from presentation to operation will determine the amount of viable intestine saved when there is a volvulus. Malrotation is diagnosed when the upper GI series demonstrates an abnormal point of attachment of the ligament of Treitz. Surgical management with a Ladd’s procedure is required to release the mesentery. This topic is covered in greater detail in Chapter 109.

Hirschsprung’s Disease

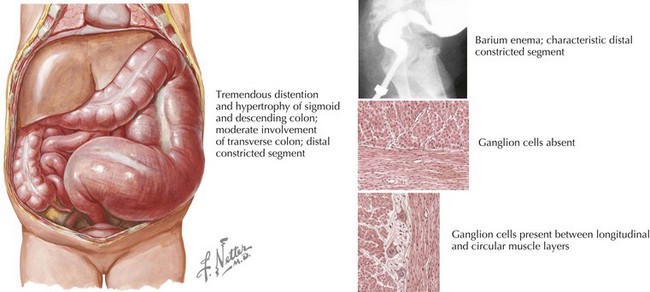

Abdominal plain radiographs may reveal dilated bowel loops or the presence of stool in the colon, and a barium enema may show a transition point in affected patients (Figure 103-3). Definitive diagnosis is made with a suction rectal biopsy to evaluate for the presence of ganglion cells. Surgical repair is required to remove the aganglionic section of bowel and restore normal peristalsis.

Meconium Ileus, Meconium Plug Syndrome, and Small Left Colon Syndrome

These entities have similar diagnostic workup that includes abdominal radiography. Key findings include intestinal distension proximal to the site of obstruction and possibly calcifications within the meconium. Barium enema may be used to better identify the point of obstruction, and it may also be therapeutic in the setting of meconium plug syndrome. In meconium ileus, contrast enema will demonstrate a small, unused colon and meconium pellets in the distal ileum. Because of the specificity of this disease for CF, genetic testing should be undertaken (see Chapter 41). If water-soluble enema fails to relieve the obstruction or if the obstruction is complicated by proximal volvulus, surgical intervention is indicated.

Abdominal Wall Defects

Clinical Presentation

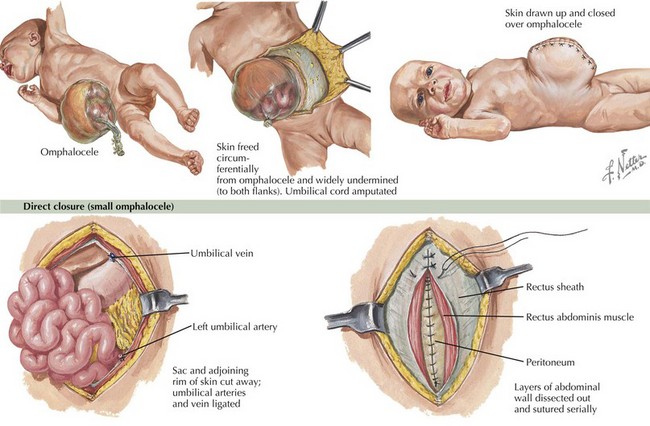

The presence of gastroschisis or omphalocele is readily apparent on physical examination, and both are often diagnosed prenatally on ultrasound (Figure 103-4). Omphalocele is characterized by an overlying membrane and a central location. Gastroschisis is displaced to the right of the umbilicus and does not have an overlying membrane.

Evaluation and Management

Gastroschisis and omphalocele require surgical correction (see Figure 103-4). Before surgical intervention, the defects should be covered and kept moist. Infants may require additional fluids given their higher-than-normal insensible losses. Preterm infants may need to be supported during a period of growth until they are large enough to undergo closure. Omphalocele has a high association with genetic syndromes; therefore, a careful physical examination and genetic evaluation are indicated.

Claud EC, Walker WA. Bacterial colonization, probiotics, and necrotizing enterocolitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42(suppl 2):S46-S52.

Dimmitt RA, Moss RL. Clinical management of necrotizing enterocolitis. NeoReviews. 2001;2:e110-e116.

Hajivassiliou CA. Intestinal obstruction in neonatal/pediatric surgery. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2003;12(4):241-253.

Jesse N, Neu J. Necrotizing enterocolitis: relationship to innate immunity, clinical features, and strategies for prevention. NeoReviews. 2006;7:e143-e149.