Disorders of the contractile structures

Resisted flexion of the elbow

Pain

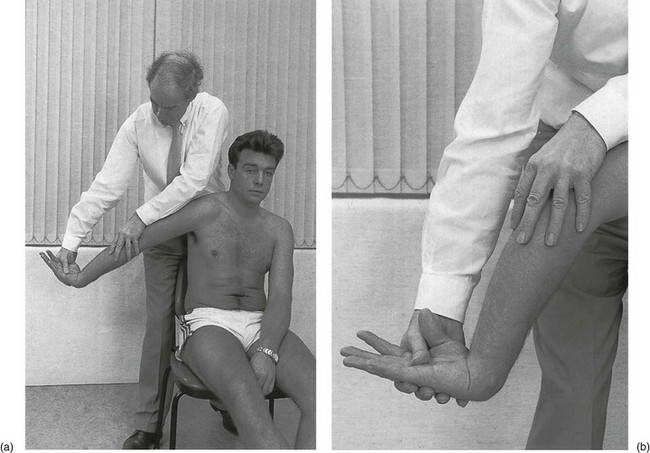

The biceps and brachialis muscles are tested during resisted flexion, which should be performed with the elbow bent at a right angle – the neutral position between flexion and extension and also the one in which elbow flexion strength is maximal1,2 – and the forearm held in active supination. This is the best position to test the biceps muscle,3 which is more often strained than the brachialis.

Electromyographic studies confirm decreased activity of the biceps when flexion is performed in pronation.4–6

Biceps muscle

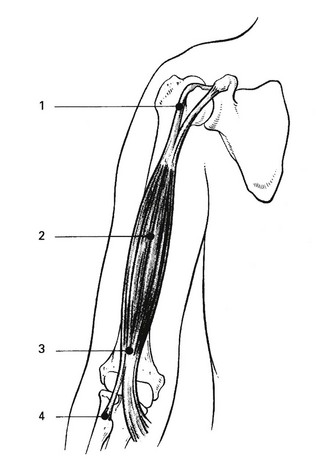

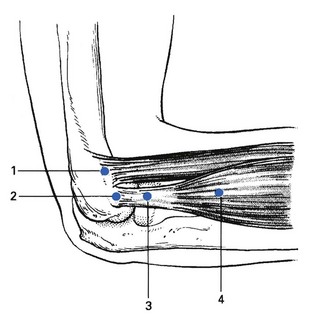

If the biceps muscle is at fault, resisted supination will also be painful. There are four possible localizations, indicated by the site of the pain (Fig. 19.1).

Pain at the shoulder

Rupture of the long head of biceps is one of the commonest tendinous ruptures. It causes scarcely any symptoms, except the appearance of a round ball of muscle at the lower part of the arm when the patient flexes the elbow. Resisted flexion remains painless and strong, the brachialis muscle still functioning as the strongest flexor of the elbow – only 8% of elbow flexion strength and approximately 21% of forearm supination strength is lost.7 Treatment is not required.

Pain at the mid-arm

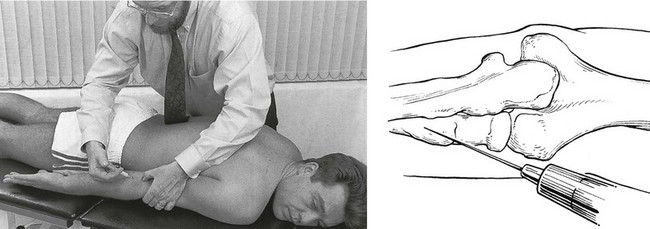

Technique: deep friction to the biceps belly

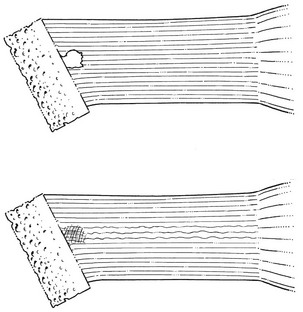

The therapist grasps the muscle belly at the point of the lesion with the ipsilateral hand in a pinching grip, holding the fingers well flexed, which enables the posterior aspect of the muscle to be reached (Fig. 19.2). The hand is then pulled anteriorly. This results in a transverse friction to the muscular fibres, which can be felt to pass under the fingers. The hand is then brought back to the starting position without losing contact with the patient’s skin. The manœuvre thus has two phases: an active phase, when the hand is pulled anteriorly, and a passive phase, when the hand is brought backwards again.

Pain at the elbow

Apart from the usual signs on examination, a localizing sign is present – pain at full passive pronation. This is the result of the bicipital insertion being pinched between the radial tuberosity and the shaft of the ulna as the radius turns over the ulna during pronation.8 Palpation is not necessary and would even be negative, as tenderness cannot be elicited by probing with a finger.

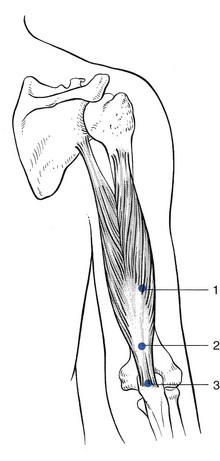

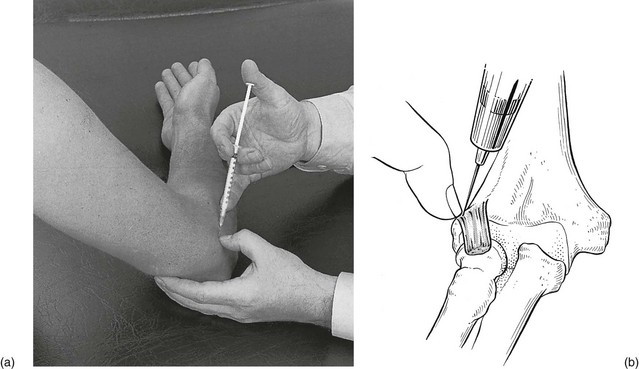

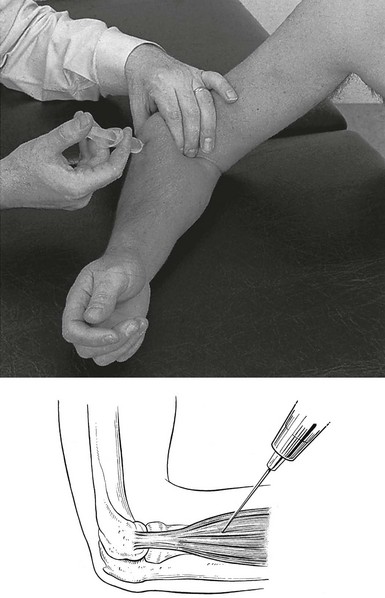

Technique: infiltration of the distal insertion of the biceps

The joint line between humerus and radius is palpated. The posterior edge of the ulna is easily felt. A point is chosen 2–3 cm further distally from the joint line and just laterally to the ulna. A 2 mL syringe is filled with triamcinolone and a thin needle, 2 cm long, is fitted. The needle is inserted at the chosen point and pushed vertically downwards until it hits the shaft of the radius, either directly or through a tendinous structure (Fig. 19.3). In the former case, the needle has to be partly withdrawn and reinserted in a slightly different direction in order to feel the tendinous resistance. Then a series of droplets is infiltrated at the tendinous insertion according to the usual infiltration technique.

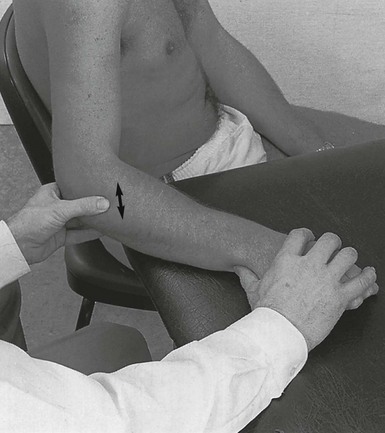

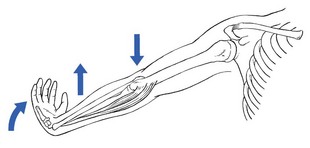

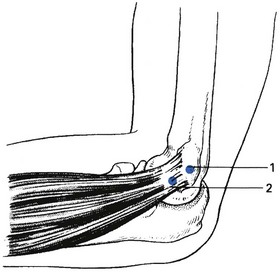

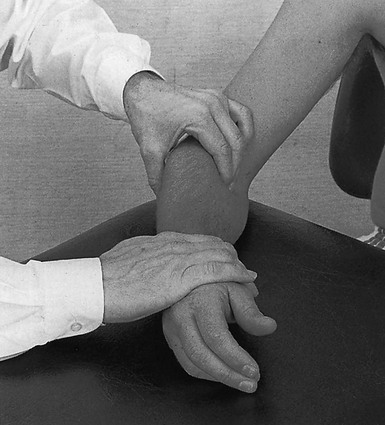

Technique: friction to the distal insertion of the biceps

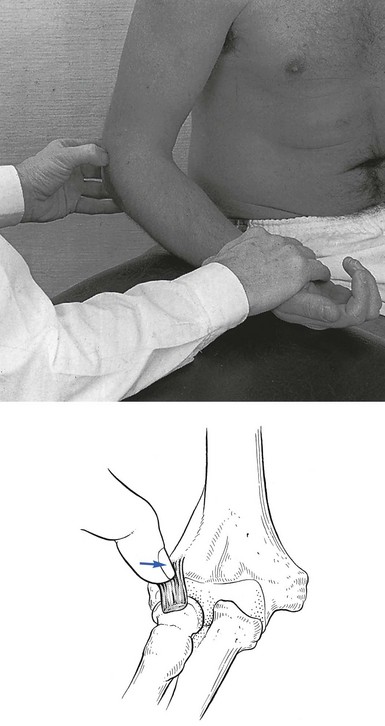

The ipsilateral hand, which grasps the patient’s forearm about the wrist, is used to perform a pronation movement. The forearm is pronated until the biceps tendon passes under the therapist’s thumb. The tendon now lies medial to it. Friction is thus performed by this indirect movement. During this part of the movement, the pressure on the tendon is augmented (active phase). The forearm is then brought back to the supinated position, while the pressure is released (passive phase). These repeated movements result in a transverse friction (Fig. 19.4), which is continued for 15 minutes.

Brachialis muscle

Treatment consists of 2 or 3 weeks’ deep transverse friction.

The brachialis muscle and heterotopic ossification

Myositis ossificans is a benign condition, characterized by heterotopic bone formation, which occurs after injury to muscle fibres, connective tissue, blood vessels and underlying periosteum.9 It occurs most often in males aged between 15 and 30 years and presents with the following triad of symptoms: pain in the affected muscle, a palpable mass and a flexion contracture.10 The history of severe contusion is helpful in the early evaluation of these patients, before radiographic changes are evident.11

When, after an injury, usually fracture,12 pain in the elbow region increases and the range of movement gradually decreases,13 this may indicate the development of myositis ossificans. An increasing firm mass in the brachialis muscle is mostly palpable in the middle or distal segment of the arm and becomes visible on the radiograph in the course of a few weeks.14 A technetium bone scan is clearly positive.15 When myositis ossificans has fully developed, only a little movement to either side of the right angle is possible and even rotations are markedly limited.

Myositis ossificans does not respond to conservative treatment and may disappear spontaneously over the course of 2 years. Lipscomb et al17 have stated that myositis ossificans in the upper extremity is very likely to resorb completely. If not, surgical excision may be performed, but only when the lesion is completely ossified, because removal of immature bone may cause extensive local recurrence.18

Brachioradialis muscle

We have never encountered a lesion of the brachioradialis muscle but a case has been described by Barbaix.19 The patient, following exertion, experienced supracondylar pain at the radial aspect of the elbow occurring during activities which included elbow flexion and simultaneous rotations. The pain could be elicited on passive extension, which was slightly limited, and on resisted flexion of the elbow. Accessory examination showed resisted supination with the forearm in full pronation more painful with a flexed elbow than with an extended one. Diagnosis was confirmed with echography and the patient responded well to infiltration with triamcinolone acetonide.

These clinical findings are compatible with an earlier electromyographic study showing electrical activity with flexion, especially with the forearm rotated in pronation.20

Weakness

Rupture

A distal biceps tendon rupture is usually at the tendinous insertion and sometimes accompanies an avulsion of the radial tuberosity.21 The lesion is reported increasingly in the current literature.22–26 The mechanism of injury is most commonly an eccentric load applied to a flexed elbow. On physical examination there may be swelling, haematoma and a ‘Popeye’ deformity of the upper arm. However, the normal contour of the distal biceps may still appear to be intact if the lacertus fibrosus is not torn.27 Range of motion is usually full unless there is severe swelling. Strength testing reveals weakness in forearm supination and, to a lesser extent, elbow flexion. The biceps squeeze test and the hook test are two physical examination manœuvres that have been shown to be sensitive and specific in diagnosing distal biceps tendon ruptures. The biceps squeeze test involves compression of the biceps muscle belly, which results in forearm supination if the tendon is intact.28 In the hook test, with the elbow actively flexed and supinated, an index finger should be able to ‘hook’ under a cord like structure in the antecubital fossa if the tendon is intact.29

The treatment of choice is surgery: anatomic repair of distal biceps tendon rupture provides consistently good results and early anatomic reconstruction can restore strength and endurance to the elbow.30–32

Resisted extension of the elbow

Pain

Triceps muscle

Lesions of the triceps muscle are rare. Three possible localizations can be differentiated by palpation (Fig. 19.5): the musculotendinous junction, which is the most common site; the body of the tendon; and the tenoperiosteal junction at the olecranon.

Technique: infiltration at the tenoperiosteal junction

A 1 mL syringe is filled with triamcinolone acetonide and a 2 cm needle is fitted. The tip of the olecranon is palpated and the tender point located. The needle is inserted 1 cm proximal to it and directed towards the olecranon (Fig. 19.6). Tendinous resistance should be felt before hitting bone. Infiltration is then carefully performed by several withdrawals and reinsertions of the needle and maintaining bony contact.

Technique: friction to the musculotendinous junction, body of tendon and tenoperiosteal junction

The patient sits next to the couch with the arm rested, the elbow held in 90° flexion. The therapist sits at a right angle to the patient’s arm. With the contralateral hand the patient’s elbow is grasped, while the other hand stabilizes the patient’s forearm. The tender spot in the triceps tendon is palpated and then the index finger, reinforced by the middle finger, is placed at the medial side of the tendon. Counterpressure with the thumb is then applied at the lateral aspect of the proximal part of the forearm (Fig. 19.7). The therapist abducts the arm and then brings it back into the side. This is the active phase and is followed by relaxation while bringing the arm back into abduction. Such repeated movement results in a transverse friction to and fro over the lesion.

Fig 19.7 Deep friction to the triceps.

Anconeus compartment syndrome

Abrahamsson et al33 reported a case of lateral elbow pain caused by a chronic compartment syndrome of the anconeus muscle. The symptoms were lateral elbow pain and muscular dysfunction during heavy work. The pain was reproduced by repeated extension of the elbow and pronation of the forearm. There was a slightly bulging mass and pronounced tenderness of the anconeus muscle, which were successfully treated by fasciotomy.

Weakness

Painful weakness

Total or partial rupture of the triceps tendon

This has been reported as a rare injury.34,35 The most common form is an avulsion from the osseous tendon insertion.36 Injury at the musculotendinous junction occurs less often.37 The most common mechanism of injury is a deceleration stress superimposed on a contracted triceps muscle.38 A palpable gap, with complete weakness of arm extension, is pathognomonic of triceps rupture. In many cases, however, the palpable defect is not noted initially because of swelling and ecchymosis.39 Early surgical repair of the injury is the treatment of choice and gives predictably good results.40,41 Sometimes the same mechanism of injury causes a triceps avulsion fracture. Apart from the same symptoms and signs, the lateral radiograph will show the presence of flecks of avulsed osseous material from the olecranon (‘flake sign’), which is almost pathognomonic of this lesion.42

Fracture of the olecranon

If the pain is the result of an injury and resisted extension of the elbow is painful and weak, the possibility of a fracture of the olecranon must be considered. Local tenderness and marked articular signs at the elbow joint will also be present: warmth, swelling and limitation of passive movements in the capsular pattern. In most cases, conservative treatment is sufficient.43

Painless weakness

A radial palsy and a C7 root palsy are the most common of the other neurological disorders.

Radial palsy

Apart from known traumatic causes, a radial palsy is quite often the result of pressure from a crutch or sleeping with the inner side of the arm pressed against a hard edge (‘Saturday-night paralysis’). In this case, resisted extension of the wrist is also very weak and may even result in wrist-drop. The condition is painless and recovers spontaneously over the course of 3–6 months. Some severe cases require neurosurgical repair (see online chapter Nerve lesions and entrapment neuropathies of the upper limb).

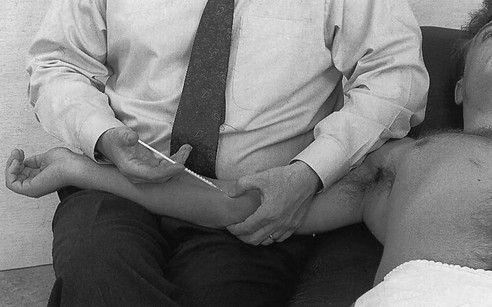

Resisted supination

To confirm the diagnosis, the test is repeated with the elbow held actively in full extension – a position which inhibits the function of the biceps. The muscle is not found to be particularly tender and therefore an infiltration with a local anaesthetic should be given (Fig. 19.8). This may effect a cure, but treatment with deep transverse friction (Fig. 19.9) is usually necessary. It is successful in 1 or 2 weeks.

Resisted pronation

Technique: friction to the pronator teres muscle

The patient sits with the arm rested on the couch. The therapist sits at a right angle to the patient’s arm. The elbow is held in 90° flexion and the forearm in neutral position between pronation and supination. The therapist palpates at the anterior aspect of the forearm for the muscle belly, which may be facilitated by an active contraction by the patient. The fingertips of two or three fingers of the contralateral hand are then placed on the tender area and counterpressure is applied with the thumb at the lateral aspect of the forearm. The forearm is stabilized with the other hand (Fig. 19.10). The friction movement is begun underneath the muscle and the fingers are pulled over the muscle towards the therapist. This is the active phase. The fingers are then brought back to the previous position (passive phase). The sequence is repeated.

Fig 19.10 Deep friction to the pronator teres.

Pain on resisted extension of the wrist

Tennis elbow

The term ‘tennis elbow’ has been used to describe a multiplicity of conditions of the elbow.

Renton,44 in 1830, was the first to describe a patient with pain along the outer forearm which increased on using the hand. In 1873, Runge, a German physician, wrote an article on ‘writer’s cramp’. He distinguished the condition from a case of 2 years’ inability to write, associated with tenderness on the lateral condyle of the humerus. Rest and electrotherapy had no effect and he then cauterized the skin over the tender area, after which the patient became well. He thought the cramp was the result of traumatic inflammation of the periosteum in this location, originally caused by a forcible supination effort and made chronic by the continual pull of the extensor muscles attached to the lateral condyle.45 Morris (1882)46 compared a condition named ‘lawn-tennis arm’ to rider’s sprain – a lesion of the adductor longus muscle at the hip – and Major also called the condition ‘lawn-tennis elbow’.47 An annotation in The Lancet (1885) drew attention to the number of people suffering from ‘tennis elbow’, whose plaintive letters had recently appeared in the lay press. From then on, the term ‘tennis elbow’ has been used to describe symptoms at the outer aspect of the elbow. Remak (1894)48 and Bernhardt (1896)49 agreed that it was a periosteal tear from occupational overuse of the extensor muscles that arise from the lateral condyle. Couderé (1896)50 called it a ‘ruptured epicondylar tendon’, Féré (1897)51 ‘épicondylalgie’, Franke (1910)52 ‘epicondylitis’. In 1921, Schmidt53 suggested superficial epicondylar bursitis, thereby incriminating the bursa described by Schreger in 1825.54 In 1922, Osgood55 and, in 1932, Carp56 believed the lesion to lie in the radiohumeral bursa, and extra-articular bursa under the extensor tendons, which was first described by Monro in 1788.57

In 1936, Cyriax58 compiled a list of no fewer than 26 different types of lesion to which the name tennis elbow had been given by 91 authors during the previous 63 years. He presented a synopsis of opinion as to the cause of tennis elbow and stated that a condition, the symptoms and signs of which are as constant as those of tennis elbow, may well be supposed to have but one background and, as a corollary, but one type of treatment.

An enormous number of articles on tennis elbow have been published in the ensuing years, describing different pathological entities such as radiohumeral bursitis, radiohumeral synovitis, irritation of the synovial fringe, degeneration of the annular and collateral ligaments, fibrillation of the articular cartilage, osteoarthrosis of the radiohumeral joint, osteochondritis dissecans, aseptic necrosis of the radial head, stenosis of the orbicular ligament, chondromalacia of the radial head and capitellum, calcific tendinitis of the extensor muscles, myofasciitis, traumatic periostitis of the lateral epicondyle, and enthesopathy of the lateral epicondyle of the humerus, among others.59–68

A new concept was introduced in 1972 when Roles and Maudsley described the ‘radial tunnel syndrome’69 (see online chapter Nerve lesions and entrapment neuropathies of the upper limb).

The most encompassing classification is perhaps that of O’Neill et al,70 who state that ‘tennis elbow or lateral epicondylitis consists clinically of pain localized in the region of the lateral aspect of the elbow with tenderness in the vicinity of the lateral epicondyle’. This vague description illustrates how unsure most authors are about the pathogenesis of tennis elbow.

Most authors consider tennis elbow as a local condition in relation to the lateral epicondyle of the humerus. However, some authors have described this condition as resulting from a cervical problem and they claim curative results with treatment to the neck. Gunn et al71 considered a tennis elbow to be caused by a reflex localization of pain from radiculopathy at the cervical spine. Several authors agreed with this point of view.72–74 Weh75 believes that the idea of a local clinical assessment of tennis elbow should be broadened to an overall vision of a functional chain consisting of cervical spine, shoulder and elbow, in which local reflex inhibition of muscles innervated by the seventh nerve root and a limitation of movement of the cervical spine are causative elements. It is quite certain that elbow pain may have a cervical origin. This should not be designated ‘tennis elbow’ but instead ‘referred elbow pain’ from the cervical spine. If clinical examination shows the elbow pain to be evoked by movements at the elbow, then the lesion must be sought there. In contrast, if cervical examination is positive, this means that cervical movements must be the cause of pain in the elbow region.

Terminology

‘Tennis elbow’ is technically a misnomer, since it most often occurs in non-tennis players: less than 5% of the patients play tennis.76–78 Even in a population of 500 tennis players complaining of lateral elbow pain, Grachaw and Pelletier found tennis elbow present in only 39.7%.79 This accords with Krämer’s findings.80 Neither is the term ‘epicondylitis’ right: at least 10% of the lesions do not lie at the epicondyle itself. Furthermore, the suffix ‘-itis’ indicates an inflammatory process, but histological analysis shows only disruption of the collagen bundles with vascular and fibroblast proliferation and without inflammation. Therefore the term ‘tendinosis’ should be preferred over ‘tendinitis’.81

Of all the patients seen in a general medical practice, 0.5% suffer from ‘tennis elbow’.82 The condition is therefore important enough to try to define it properly. The lesion lies at the elbow, in the structures controlling wrist extension and radial deviation (extensores carpi radiales). Theoretically, the lesion could also lie in the ulnar deviators or in the extensors of the fingers but this is much less common and should be separately named: for example, lesion of the extensor carpi ulnaris muscle, lesions of the extensor digitorum muscle.

Pathological features

It is generally believed that tennis elbow is an overuse phenomenon caused by repeated contractions of the radial extensors of the wrist,61,83 and especially of the extensor carpi radialis brevis.84 Post-traumatic causes have also been described.85 In the early stages, when the tissue attempts repair, and often just as the tear begins to unite, continued muscular contraction pulls the healing surfaces apart once more. This results in the formation of a painful scar with self-perpetuating inflammation (Cyriax86: p. 178). Cyriax’s view was confirmed by Coonrad and Hooper in 1973.76

More recent observations during surgery have led Nirschl to classify this condition mostly under the heading ‘tendinosis’ rather than tendinitis: surgical inspection shows a typically ‘grayish color and homogenous and generally edematous and friable tissue’ indicating angiofibroblastic invasion – fibroblasts and vascular granulation-like tissue.87–89 Inflammatory cells are not usually found.90

History

The patient is usually between 30 and 60 years,91,92 and seldom under 20 or over 70. As the lesion is the result of overuse, the patient does not notice the pain the moment a tennis elbow develops but rather a few days later. A pain is described starting at the outer aspect of the elbow and radiating down the posterior aspect of the forearm, very often as far as the dorsum of the hand. Pain may be felt in the long and ring fingers. It is evoked by grasping, pinching and lifting – the movements that involve extension of the wrist and in which the wrist extensors merely act as stabilizers of the joint.

Functional examination

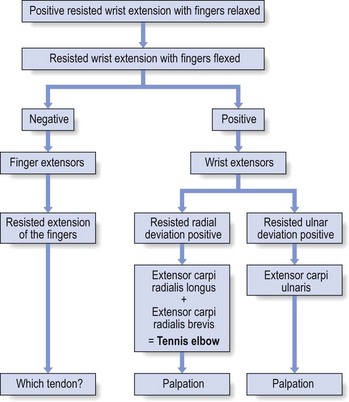

The next approach is to differentiate the radial extensors from the ulnar extensor using two accessory tests. Resisted radial deviation is compared with resisted ulnar deviation, the wrist being held in the neutral position between flexion and extension. In the rare circumstance that resisted ulnar deviation is painful, the lesion lies in the extensor carpi ulnaris muscle. Much more frequently, resisted radial deviation is painful, which indicates a lesion in either the extensor carpi radialis longus or the extensor carpi radialis brevis – the structures involved in tennis elbow (Fig. 19.11).

Fig 19.11 Clinical examination of tennis elbow.

Palpation

The exact location is revealed by palpation. The palpatory manœuvres must be confined to the structures at fault: the extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis. In that the lateral aspect of the elbow is very often tender to the touch, even in those without a lesion, palpation is sometimes misleading. One elbow should be compared with the other, as should possible locations. In corpulent women, it may be difficult to define the lateral epicondyle. The palpation techniques are identical to the friction techniques (see Treatment, below) although it might sometimes be necessary to put the elbow further into extension to be able to reach the tender spot.

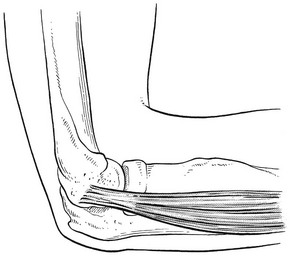

Practice shows that a tennis elbow has four different localizations (Fig. 19.12). Double lesions, however, are not at all uncommon. On palpation from proximal to distal, a tender spot can be found at one of the following places:

• just proximal to the epicondyle along the supracondylar ridge at the anterior aspect – i.e. the origin of the extensor carpi radialis longus. This structure feels like a muscular rather than a tendinous tissue (type I).

• at the anterior aspect of the lateral epicondyle – the tenoperiosteal origin of the extensor carpi radialis brevis. In this instance palpation must be precisely at the origin of the tendon itself. Palpation of the lateral or posterior aspect of the epicondyle may also be positive, which is merely ‘associated’ tenderness. This disappears as soon as the lesion is cured. The tenoperiosteal variety at the epicondyle itself is by far the most common localization of tennis elbow (type II).

• level with the radiohumeral joint line and over the head of the radius – the body of the tendon of the extensor carpi radialis brevis, lying in between other tendinous structures (type III).

• level with the neck of the radius and a few centimetres distally – the upper part of the muscle bellies of extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis (type IV).

Experience shows that type I occurs in 1% of cases, type II in 90%, type III in 1% and type IV in 8% (Cyriax86: p. 178).

Treatment of type I (supracondylar) tennis elbow

Treatment of type II (tenoperiosteal) tennis elbow

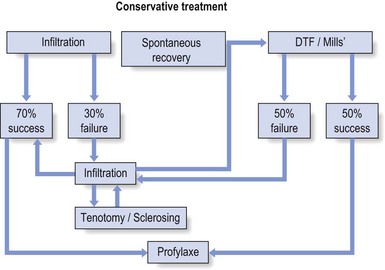

Treatment of the tenoperiosteal type of tennis elbow varies from very easy to very complicated. The choice of treatment depends on different factors, such as age, activities and duration of the symptoms. As the condition tends to resolve spontaneously, this possibility should be presented to the patient. Active treatment consists of infiltration with triamcinolone and Mills’s manipulation. Recurrent or refractory cases may need other approaches, including infiltration with a sclerosant solution, percutaneous tenotomy and partial immobilization – taping and bracing (see Treatment procedures, p. 312).

Natural evolution

The tenoperiosteal variety is the only type of tennis elbow that has a tendency to spontaneous cure93 (Fig. 19.14); this may take a year in patients under 60 and up to 2 years when the patient is older than this. After full spontaneous recovery, a second attack is rare. However, infiltration of any steroid solution inhibits the mechanism of spontaneous cure. The patient should be told about the possibility of spontaneous recovery, certainly if symptoms have been present for some time. Waiting, meanwhile sparing the elbow as much as possible, may be the preferred option. Cyriax86 (his p. 179) explains the mechanism of spontaneous recovery as follows: as the result of the many contractions of the extensors of the wrist, which put tension on the healing breach, the gap between the two edges gradually widens. Finally the two surfaces cease to lie in apposition and the tension on the scar ceases. The gap now fills with fibrous tissue. The painful scar is now embedded and heals with permanent lengthening of some tendinous fibres. In consequence, the strain no longer falls on that part of the tendon. Recurrence is prevented by this structural alteration. Because several muscles are attached here, slight permanent lengthening of the section of tendon relevant to only one muscle does not weaken the power to control the wrist.

Infiltration with triamcinolone suspension

Until 1952 there was no alternative to deep transverse friction in the treatment of tendinous lesions. For many years a means of reducing a localized area of unwanted traumatic inflammation had been sought. In 1952, Cyriax and Troisier94 suggested the use of steroid infiltration as a treatment for tennis elbow. After the infiltration, the scar remains in place but the inflammation ceases. Because the steroid is a suspension of insoluble particles, its action is confined to the structure which is infiltrated without much effect on or spread to the adjacent structures.

In the following decades, steroid infiltration gained a bad reputation. Some authors therefore advise that the injection be given in such a way that the solution will bathe the underlying tendon rather than being injected into the tendon itself.95 This technique may easily lead to the development of lipoatrophy and depigmentation of the skin. All these side effects can be avoided by using the smallest possible amount of weak steroid and precise infiltration into the tendon itself.

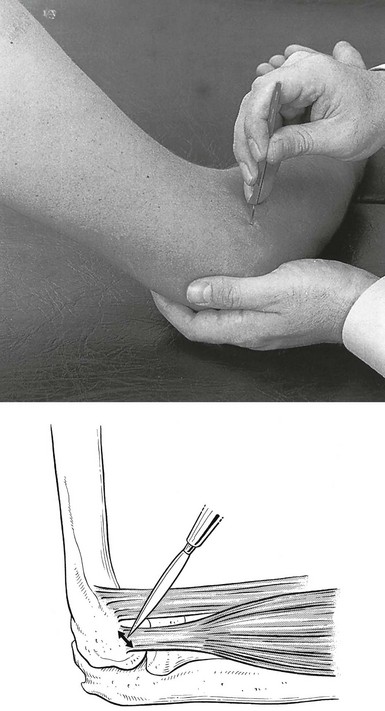

Technique: infiltration

A 1 mL tuberculin syringe is filled with triamcinolone suspension and fitted with a thin needle 2 cm in length. The thumb is placed at the tender spot. The needle is thrust in vertically until it pierces the tendinous insertion and hits bone (Fig. 19.15). As one droplet is infiltrated, the appearance of a tiny bulge is felt for with the palpating thumb, confirming that the correct spot has been found. By half-withdrawing and reinserting the needle at slightly different angles, the entire lesion, which must be envisaged as a three-dimensional object, is infiltrated. Each time a droplet is injected, its exact position should be determined using the thumb. Considerable pressure sometimes has to be exerted on the syringe.

Results

Our personal experience is that 1–3 steroid infiltrations give full relief in all cases of uncomplicated tennis elbow. However, only two-thirds of patients remain asymptomatic. The rest will relapse within 2–6 months. Although renewed infiltrations may be of most benefit, there will remain some refractory cases that are difficult to treat (see p. 310). The prerequisites for success are: accurate diagnosis and localization of the lesion, correct infiltration technique, and a completely negative test on re-examination. A similar success rate was found by Troisier in 199196: in a series of 257 patients, infiltration with corticosteroids gave full relief in all cases but the recurrence rate was 66.7%, although 67% of these recurred only once or twice.

Over the last few decades the effectiveness of steroid infiltration has been investigated via multiple controlled trials. All showed that steroid injections produced quick and significant pain relief in the short term, but that long-term outcomes are less clear. Hay et al performed a multicentre pragmatic randomized controlled trial of local corticosteroid injection and naproxen in 164 patients. They came to the conclusion that early local corticosteroid injection is much more effective in the first weeks than treatment with naproxen or placebo, but that the outcome at 1 year was the same in all groups.97 This confirms the findings of Assendelft et al98 and Verhaar et al.99

In another randomized clinical trial, Smidt et al claimed that the long-term outcomes of steroid injections might be poor due to the high number of relapses.100 The study by Tonks et al was very positive for steroid injections but did not follow up the patients beyond 7 weeks,101 while Altay et al reported that local steroid injection produced excellent pain relief at 1 year.102 In a prospective randomized study Dogramaci et al compared three different methods of injection: a local injection of triamcinolone, a peppering infiltration of local anaesthetic and a peppering infiltration of triamcinolone. The peppering infiltrations with triamcinolone produced superior clinical results with cure in 84% of cases, whereas corticosteroid injection was only effective in 36% and peppering with lidocaine alone gave good results in 48%.103

Mills’s manipulation

Several authors, such as Cyriax, Mills, Mennell, Stoddard and Kaltenborn, have proposed manipulation as a treatment for tennis elbow.58,104–108 Although it is based on different pathological premises, they found that manipulative treatment could lead to good results. Manipulation, preceded by deep transverse friction, was Cyriax’s treatment of choice before infiltration with steroids was found to be effective in 1952. He intended to stretch the extensor carpi radialis brevis tendon maximally in order to try to pull apart the two surfaces of the painful scar. This would thus imitate and speed up the mechanism of spontaneous recovery (see p. 307).

Several manipulations have been compared and it seems that Mills’s manipulation, as described by Cyriax and for the indications which he describes, has the greatest potential to stretch the affected tendon with the least potential for harm to the joint.109 Mills was an orthopaedic surgeon who described his manipulation technique in 1928 with the intention of realigning a torn section of the annular ligament, which he regarded as out of place.104 Cyriax later discontinued the use of his own initial manipulation method and advocated the use of his modification of Mills’s manœuvre.

The manipulation is preceded by deep transverse friction because of its desensitizing and softening effect, which makes the actual manœuvre less painful and therefore more tolerable. Friction alone is ineffective. This second type of tennis elbow is the only tenoperiosteal tear in the body that is not treated by deep transverse friction alone, and the only one for which manipulation has any effect. Some authors claim good results with stretching of the wrist extensors as home exercise following the treatment.110

Technique: preparative deep friction

The thumb is well flexed and the thumb tip placed on the tender spot at the lateral edge of the epicondyle. The thumb is then brought over the anterior aspect of the epicondyle and imparts friction by moving medially over the bone (Fig. 19.16). The amplitude of the friction is only a few millimetres. Pressure is exerted vertically downwards. The therapist should start gently, because of the painfulness of the condition, and gradually increase the pressure.

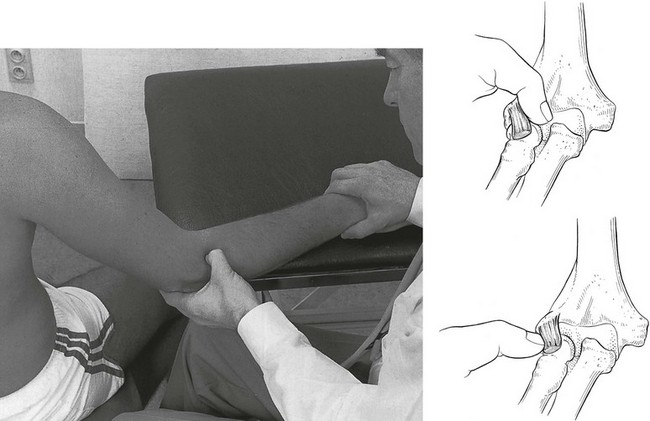

Technique: manipulation

The patient sits on a chair and the therapist stands behind. The patient’s arm is abducted and also put in internal rotation. The forearm is then fully pronated and the wrist flexed. The patient’s hand is grasped with the ipsilateral hand by bringing the thumb between the patient’s thumb and index finger, so that the therapist’s thumb is on the patient’s palm. Consequently the fingers come to lie at the dorsum of the hand. This position enables the therapist to maintain full flexion at the patient’s wrist at the moment of manipulation. The contralateral hand is then placed on top of the olecranon (Fig. 19.17). By moving both hands in opposite directions, the elbow is extended and the extensor muscles are thus stretched.

A quick thrust towards elbow extension (Fig. 19.18) is then performed by moving both hands in opposite directions. A crack is very often heard, indicating the rupturing of some tendinous fibres. This manipulation is carried out once at each attendance. It usually takes 8–15 sessions for the patient to be cured but some cases require 20–30 treatments and not every tenoperiosteal tennis elbow responds well.

Troisier96 reported a series of 131 cases in which good and excellent results were achieved in 63% by deep transverse friction and manipulation. A recent randomized clinical trial compared the effectiveness of deep transverse friction massage with Mills’s manipulation versus phonophoresis with supervised exercise. Whereas both groups improved significantly from the initiation of treatment, a between-group comparison revealed significantly greater improvements regarding pain, pain-free grip and functional status for the experimental group compared to the control group.111

Refractory tennis elbow

Infiltration with a sclerosant solution

The intention is no longer to reduce inflammation of the scar but to provoke the formation of dense adhesive scarring, which engulfs the original scar, using the irritant effect of hypertonic dextrose. The beneficial result may also stem from the powerful destructive effect of phenol on the small unmyelinated pain fibres.112

Recent studies have demonstrated that 1–2 injections with a sclerosant solution effectively decreased elbow pain and improved strength testing in subjects with refractory tennis elbow compared to control injections.113,114

Tenotomy

If all other means have been tried without lasting effect, percutaneous tenotomy under local anaesthesia is worth consideration. This is a very simple operation, performed on an ambulant patient. The extensor carpi radialis brevis tendon at the anterior aspect of the lateral epicondyle is divided across its whole width. It is immediately followed by Mills’s manipulation to ensure complete separation of the two cut ends. This treatment again imitates the mechanism of spontaneous cure. A study by Daubinet of 18 tennis elbow patients who did not respond to conservative treatment showed the effectiveness of insertion–tenotomy of the extensor carpi radialis brevis.115 A prospective long-term follow-up study by Verhaar et al claims gratifying results and a low rate of complications with lateral extensor release as a simple outpatient procedure. They consider it to be the operation of choice for the treatment of long-standing tennis elbow.116 Dunkow et al conducted a prospective randomized controlled trial of 47 patients with tennis elbow, who underwent either a formal open release or a percutaneous tenotomy. They concluded that the percutaneous procedure is a quicker and simpler procedure to undertake and produces significantly better results.117 Other authors also claim good to excellent results with percutaneous release of the common extensor origin for long-standing symptoms.118–122

Technique: tenotomy123

A small, thin, double-edged tenotome is then thrust through the skin into the dense tendinous tissue in the same way the needle was introduced – vertically. The tenotome is moved further down until it touches bone (Fig. 19.19). By moving the tip of the tenotome up and down along the bone of the epicondyle in a perpendicular way, the tendon of the extensor carpi radialis brevis is divided transversely across its entire width. The small lancet is then removed and the bleeding, if present, stopped by pressure.

Fig 19.19 Tenotomy.

Extracorporeal shock wave therapy

Attempts are made with extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) to treat resistant cases. The patient receives 500–3000 shock waves of 0.08–0.12 mJ/mm2 three times at weekly intervals. Some authors consider this a useful conservative alternative in the treatment of tennis elbow.124–126 However, more recent randomized clinical studies comparing different extracorporeal shock wave regimens with placebo did not show strong statistical evidence in favour of ESWT.127–129

Bracing and taping

Through the years, tape and braces have been used to treat injuries suffered by athletes. In the early stages of the use of external support systems, physicians and certified athletic trainers used mostly trial and error and intuition to provide support for the injured area. Nowadays, interest in this aspect of preventive sports medicine has increased, and sound scientific principles have been used to improve the design and effectiveness of external support systems.130,131

At the elbow, a constricting band can be applied to the proximal part of the forearm (Fig. 19.20). It acts as a counterforce brace, constraining full muscular expansion and therefore decreasing intrinsic muscular force to the sensitive area in the forearm extensors. The intent is to cause the extensor mechanism on the lateral side of the elbow to work at the point where the band is attached, rather than at its point of origin on the lateral condyle. We consider the use of a counterbrace to be a valuable method for preventing recurrence because it causes improvement in wrist extension and grip strength with positive biomechanical effects.132–135

Fig 19.20 Counterforce brace for tennis elbow.

Special circumstances

There are two rare types of lateral elbow pain that are worth considering here.

Tenoperiosteal lesion of the extensor carpi radialis brevis with limitation of movement

This is encountered from time to time. If the limitation is in the capsular pattern, involvement of the capsule is suggested. This possibility will have been confirmed recently by arthroscopic examination.136 If this is the case, the capsule should be treated first. If the limitation follows a non-capsular pattern, it may be caused either by a loose body limiting mostly extension, or by a cyst. The loose body can be manipulated. A cyst gives rise to a few degrees’ limitation of passive extension of the elbow. The end-feel is softish, sometimes even a bit springy. Palpation usually reveals a cystic swelling under the origin of the tendon.

Treatment procedure for type II tennis elbow

There are three therapeutic options for a type II tennis elbow (Fig. 19.21):

1. Waiting for spontaneous cure. Tennis elbow is a self-limiting disorder that is usually spontaneously cured in 1–2 years. Therefore, in a mild case of lateral epicondylitis that is present for several months, it is worthwhile waiting before giving active treatment, and advising the patient to wear a counterbrace during activities.137

2. Treatment with triamcinolone infiltrations. Immediate relief is always obtained, provided the diagnosis and the applied technique are correct. However, this does not mean that all cured patients with type II tennis elbow remain well. The recurrence rate is high if the procedure (repeated reassessment and treatment), together with good secondary prophylaxis, is not properly followed. With a good infiltration technique and consequent procedure, complete and lasting cure is obtained in more than 70% of cases. If the condition recurs a few months after complete cure, triamcinolone infiltrations can be applied again. If relapses are very frequent, the case must be regarded as refractory and another treatment form should be considered: sclerosing injections or tenotomy.

3. Mills’s manipulation. This form of treatment has a success rate of about 50%. However, there are no recurrences after complete cure. Mills’s manipulation and triamcinolone infiltrations are interchangeable but are never applied at the same time.

Treatment of type III (tendinous) tennis elbow

Technique: deep friction

The therapist takes hold of the patient’s elbow with the contralateral hand. Counterpressure is applied at the medial aspect of the elbow with the fingers. With the flexed thumb, palpation is carried out at the tender spot. The therapist starts with the thumb at the medial aspect of the tendon and the friction is applied by pulling the thumb towards him, so that it slips over the tendon (Fig. 19.22). The thumb is then relaxed and the same movement started again.

Treatment of type IV (muscular) tennis elbow

The treatment of choice is infiltration with 10 mL of a local anaesthetic in the upper part of the belly of the extensor carpi radialis muscles. Two to four weekly infiltrations usually give lasting relief (Fig. 19.23).

Deep transverse friction is an alternative treatment; it is difficult, painful and not always curative. It is performed with a pinching grip (Fig. 19.24).

Technique: infiltration of the extensor carpi radialis muscle belly

The patient sits with the elbow resting on the couch. The elbow is flexed at a right angle and supinated. A 10 mL syringe is filled with 0.5% procaine and a 5 cm, thin needle is fitted. The tender spot is held pinched up by the therapist’s thumb and index finger. The needle is inserted obliquely through the belly of the brachioradialis muscle until the point strikes the radius. It is then slightly withdrawn to lie between the fingertips (see Fig. 19.23). The solution is now infiltrated fanwise with different withdrawals and reinsertions so that the entire lesion is covered.

Lesion of the extensor carpi ulnaris muscle

Occasionally, resisted extension and resisted ulnar deviation of the wrist are painful at the outer aspect of the elbow. This indicates a lesion of the extensor carpi ulnaris muscle, usually at its tenoperiosteal origin at the posterior aspect of the lateral epicondyle of the humerus (Fig. 19.25) or, more rarely, at the olecranon. Palpation will, of course, disclose the exact site of the lesion.

Fig 19.25 The extensor carpi ulnaris muscle.

Treatment consists of either infiltration with triamcinolone suspension or deep transverse friction.

Resisted flexion of the wrist

Pain

Resisted flexion of the wrist (with the elbow held in extension) causing pain at the medial aspect of the elbow indicates a lesion of the common flexor tendon, which originates mainly from the medial epicondyle. The lesion is known as medial epicondylitis or golfer’s elbow. The disorder is diagnosed 7–10 times less often than lateral epicondylitis.138 Although golfer’s elbow may affect patients from 12 to 80 years of age, it is most commonly seen in the 40–50-year age group.78 The condition has been attributed to repetitive forearm pronation and wrist flexion.139,140 As in tennis elbow, it follows a series of repeated (often occupational) strains,141 rather than a single injury. Histological analysis shows pathological changes in the common flexor tendon: micro-tearing with disruption of the collagen bundles, vascular and fibroblast proliferation, focal hyaline degeneration and an incomplete reparative process. As in tennis elbow, these changes have been called ‘angiofibroblastic hyperplasia’ and, as there is no evidence of any inflammatory process, the term ‘tendinosis’ is preferred over ‘tendinitis’.142

Palpation of the medial epicondyle is necessary to find the exact spot, which is usually very localized. There are two possible sites (Fig. 19.26):

• The tenoperiosteal variety: the tender spot is found at the anterior aspect of the medial epicondyle of the humerus at the origin of the common flexor tendon.

• The musculotendinous variety: the tender spot is 5 mm farther down, level with the inferior edge of the epicondyle. This is the musculotendinous junction (the common tendon diverging immediately below its origin into the muscle belly).

Treatment

Tenoperiosteal junction

The treatment of choice is one or two infiltrations with 1 mL of triamcinolone suspension (Fig. 19.27). The alternative is deep transverse friction (Fig. 19.28). Very often, 6–12 sessions, 2–3 times a week, are needed. The results of surgical treatment are poor.143,144

References

1. McGarvey, SR, Morrey, BF, Askew, LJ, An, KN, Reliability of isometric strength testing – temporal factors and strength variation. Clin Orthop 1984; 185:301. ![]()

2. Motzkin, NE, Cahalan, TD, Morrey, BF, et al, Isometric and isokinetic endurance testing of the forearm complex. Am J Sports Med 1991; 19:107. ![]()

3. Kapandji, IA. Physiologie articulaire, vol 1: Membre supérieur, 5th ed. Paris: Maloine; 1987.

4. Stevens, A, Stijns, H, Reybrouck, T, et al, A polyelectromyographical study of the arm muscles at gradual isometric loading. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol 1973; 13:465. ![]()

5. Maton, B, Bouisset, S, The distribution of activity among the muscles of a single group during isometric contraction. Eur J Appl Physiol 1977; 37:101. ![]()

6. Funk, DA, An, KN, Morrey, BF, Daube, JR, Electromyographic analysis of muscles across the elbow joint. J Orthop Res 1987; 5:529. ![]()

7. Mariani, EM, Cofield, RH, Askew, LJ, et al, Rupture of the tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii, surgical versus nonsurgical treatment. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1988; 228:233. ![]()

8. Seiler, JG, 3rd., Parker, LM, Chamberland, PD, et al, The distal biceps tendon. Two potential mechanisms involved in its rupture: arterial supply and mechanical impingement. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1995;4(3):149–156. ![]()

9. Gilmer, W, Anderson, L. Reactions of the somatic tissue which progress to bone formation. South Med J. 1959; 52:1432.

10. Huss, CD, Puhl, JJ, Myositis ossificans of the upper arm. Am J Sports Med. 1980;8(6):419. ![]()

11. Weinstein, L, Fraerman, S, Difficulties in early diagnosis of myositis ossificans. JAMA 1954; 154:994. ![]()

12. Morrey, BF. Ectopic ossification about the elbow. In: Morrey BF, ed. The Elbow and its Disorders. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:437–446.

13. Orzel, JA, Rudd, TG, Heterotopic bone formation: clinical, laboratory, and imaging correlation. J Nucl Med 1985; 26:125. ![]()

14. Donatelli, R, Wooden, MJ. Orthopaedic Physical Therapy. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1989.

15. Freed, JH, Hahn, H, Meneter, R, Dillon, T, The use of the three phase bone scan in the early diagnosis of heterotopic ossification (HO) and in the evaluation of didronel therapy. Paraplegia 1982; 20:208. ![]()

16. Pritchard, DJ, Krishnan Unni, K. Neoplasms of the elbow. In: Morrey BF, ed. The Elbow and its Disorders. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:886–888.

17. Lipscomb, A, Thomas, E, Johnson, R, Treatment of myositis ossificans traumatica in athletes. Am J Sports Med 1976; 4:111. ![]()

18. Park, KS, Kang, SG, Cho, CS, Kim, HY, Clinical images: myositis ossificans of the upper extremity. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(7):2454. ![]()

19. Barbaix, E. Radial epicondylitis due to a lesion of the brachioradialis muscle. Geneeskd Sport. 1995; 28(6):169–170.

20. De Sousa, OM, De Moraes, JL, De Moraes, VFL, Electromyographic study of the brachioradialis muscle. Anat Rec 1961; 139:125. ![]()

21. Hempel, K, Schwenke, K, Über Abrisse der distalen Bizepssehne. Arch Orthop Unfallchir 1974; 79:313. ![]()

22. Leighton, MM, Bush-Joseph, CA, Bach, BR, Jr., Distal biceps brachii repair: results of dominant and nondominant extremities. Clin Orthop 1995; 317:114–121. ![]()

23. Le Huec, JC, Moinard, M, Liquois, F, et al, Distal rupture of the tendon of biceps brachii: evaluation by MRI and the results of repair. J Bone Joint Surg 1996; 78B:767–770. ![]()

24. Hang, DW, Bach, BR, Jr., Bojchuk, J, Repair of chronic distal biceps brachii tendon rupture using free autogenous semitendinosus tendon. Clin Orthop 1996; 323:188–191. ![]()

25. Straugh, RJ, Michelson, H, Rosenwasser, MP, Repair of rupture of the distal tendon of the biceps brachii. Review of the literature and report of three cases treated with a single anterior incision and suture anchors. Am J Orthop 1997; 26:151–156. ![]()

26. Morrey, BF. Injury of the flexors of the elbow: biceps in tendon injury. In: Morrey BF, ed. The Elbow and its Disorders. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:468–478.

27. Quach, T, Jazayeri, R, Sherman, OH, Rosen, JE, Distal biceps tendon injuries – current treatment options. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2010;68(2):103–111. ![]()

28. Ruland, RT, Dunbar, RP, Bowen, JD, The biceps squeeze test for diagnosis of distal biceps tendon ruptures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2005; 437:128–131. ![]()

29. O’Driscoll, SW, Goncalves, LB, Dietz, P, The hook test for distal biceps tendon avulsion. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(11):1865–1869. ![]()

30. Baker, BE, Bierwagen, D, Rupture of the distal tendon of the biceps brachii. J Bone Joint Surg 1985; 67A:414. ![]()

31. Agins, HJ, Chess, JL, Hoekstra, DV, Teitge, RA, Rupture of the distal insertion of the biceps brachii tendon. Clin Orthop 1988; 234:34. ![]()

32. Chillemi, C, Marinelli, M, De Cupis, V, Rupture of the distal biceps brachii tendon: conservative treatment versus anatomic reinsertion – clinical and radiological evaluation after 2 years. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2007;127(8):705–708. ![]()

33. Abrahamsson, SO, Sollerman, C, Söderberg, T, et al, Lateral elbow pain caused by anconeus compartment syndrome, a case report. Acta Orthop Scand 1987; 58:589. ![]()

34. Bach, BR, Jr., Warren, RF, Wickiewicz, TL, Triceps rupture, a case report and literature review. Am J Sports Med. 1987;15(3):725–727. ![]()

35. Herrick, RT, Herrick, S, Ruptured triceps in a powerlifter presenting as cubital tunnel syndrome: a case report. Am J Sports Med 1987; 15:514. ![]()

36. Louis, DS, Peck, D, Triceps avulsion fracture in a weight-lifter. Orthopedics. 1992;15(2):207–208. ![]()

37. Wagner, JR, Cooney, WP, Rupture of the triceps muscle at the musculotendinous junction: a case report. J Hand Surg 1997; 22A:341. ![]()

38. Farrar, EL, 3rd., Lippert, FG, 3rd., Avulsion of the triceps tendon. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1981; 161:242–246. ![]()

39. Sharma, SC, Singh, R, Goel, T, Singh, H, Missed diagnosis of triceps tendon rupture: a case report and review of literature. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2005; 13:307–309. ![]()

40. Carpentier, E, Tourne, Y, Avulsion traumatique du tendon tricipital brachial: à propos d’un cas. Ann Chir Main Memb Super. 1992;11(2):163–165. ![]()

41. van Riet, RP, Morrey, BF, Ho, E, O’Driscoll, SW, Surgical treatment of distal triceps ruptures. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003; 85-A:1961–1967. ![]()

42. Pina, A, Garcia, I, Sabater, M, Traumatic avulsion of the triceps brachii. J Orthop Trauma. 2002;16(4):273–276. ![]()

43. Nuber, GW, Diment, MT, Olecranon stress fractures in throwers. A report of two cases and a review of literature. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1992; 278:58–61. ![]()

44. Renton, J. Observations on acupuncturation. Edinb Med J. 1830; 34:100.

45. Runge, F. Zur Genese und Behandlung des Schreibekrampfes. Berl Klin Wochenschr. 1873; 10:245.

46. Morris, H. Rider’s sprain. Lancet. 1882; ii:557.

47. Major, HP. Lawntennis elbow. BMJ. 1883; 2:557.

48. Remak, E. Beschöftigungsneurosen. Vienna: Urban & Schwarzenberg; 1894.

49. Bernhardt, M. Über eine wenig bekannte Form der Beschöftigungsneuralgie. Neurol Zentralbl. 1896; 15:13.

50. Couderé, A. Étude sur un nouvel accident professionnel des maîtres d’armes dû à la rupture probable et partielle du tendon epicondylien. Bordeaux: Thesis; 1896.

51. Féré, G. Note sur l’épicondylalgie. Rev Méd. 1897; 17:144.

52. Franke, F. Über Epicondylitis Humeri. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1910; 36:13.

53. Schmidt, J. Bursitis calcarea am Epicondylus externus Humeri. Arch Orthop Unfallchir. 1921; 19:215.

54. Schreger, GB. De Bursis Mucosis Subcutaneis. Erlangen: Palmand Enke; 1825.

55. Osgood, RB. Radiohumeral bursitis, epicondylitis, epicondylalgia (tennis elbow). Arch Surg Chic. 1922; 4:420.

56. Carp, L. Tennis elbow caused by radiohumeral bursitis. Arch Surg. 1932; 24:905.

57. Monro, A. Description of all Bursae Mucosae of the Human Body. Edinburgh: Elliott; 1788.

58. Cyriax, JH. The pathology and treatment of tennis elbow. J Bone Joint Surg. 1936; 18:921.

59. Bosworth, DM, The role of the orbicular ligament in tennis elbow. J Bone Joint Surg 1955; 37A:527. ![]()

60. Goldie, I, Epicondylitis lateralis humeri (epicondylalgia or tennis elbow). Acta Chir Scand. 1964;(Suppl 339). ![]()

61. Friedlander, HL, Reid, RL, Cape, RF, Tennis elbow. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1967; 51:109. ![]()

62. Nirschl, RP, Tennis elbow. Orthop Clin North Am 1973; 4:767–787. ![]()

63. Boyd, HB, McLeod, AC, Tennis elbow. J Bone Joint Surg 1973; 55A:1183. ![]()

64. Gardner, RC, Tennis elbow: diagnosis, pathology, and treatment. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1970; 72:248. ![]()

65. La Freniere, JG, Tennis elbow – evaluation, treatment and prevention. Phys Ther 1979; 59:742. ![]()

66. Kamien, M, A rational management of tennis elbow. Sports Med. 1990;9(3):173. ![]()

67. Wittenberg, RH, Schaal, S, Muhr, G, Surgical treatment of persistent elbow epicondylitis. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1992; 278:73–80. ![]()

68. Ernst, E, Conservative therapy for tennis elbow. Br J Clin Pract. 1992;46(1):55–57. ![]()

69. Roles, NC, Maudsley, RH, Radial tunnel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg 1972; 54B:499. ![]()

70. O’Neill, J, Sarkar, K, Uhtoff, HK, A retrospective study of surgically treated causes of tennis elbow. Acta Orthop Belg 1980; 46:189. ![]()

71. Gunn, CC, Milbrandt, WE, Tennis elbow and the cervical spine. Can Med Assoc J 1976; 114:803. ![]()

72. Bouillier de Branche, B. Étude de 58 dossiers de tendinites épycondyliennes traitées par manipulations cervicales. Ann Réadapt Méd Phys. 1986; 29:75.

73. Maigne, R. Les Manipulations dans le traitement des épicondylites: le facteur cervical, le facteur articulaire. Ann Réadapt Méd Phys. 1986; 29:57.

74. Murray-Leslie, CF, Wright, V, Carpal tunnel syndrome, humeral epicondylitis, and the cervical spine: a study of clinical and dimensional relations. BMJ 1976; 1:1439–1442. ![]()

75. Weh, L. Funktionelle Phänomene bei der Epicondylopathia Hemeri radialis. Disch Z Sportmed. 1989; 8:276.

76. Coonrad, RW, Hooper, WR, Tennis elbow: its course, natural history, conservative and surgical management. J Bone Joint Surg 1973; 55A:1177. ![]()

77. Kivi, P, The etiology and conservative treatment of humeral epicondylitis. Scan J Rehabil Med 1982; 15:37–41. ![]()

78. Gellman, H, Tennis elbow (lateral epicondylitis). Orthop Clin North Am. 1992;23(1):75–81. ![]()

79. Grachaw, WK, Pelletier, D, An epidemiologic study of tennis elbow. Am J Sports Med 1979; 4:234. ![]()

80. Krämer, J, Schmitz-Beuting, J. Überbelastungsschäden am Bewegungsapparat bei Tennisspielern. Dtsch Z Sportmed. 1979; 2:44.

81. Nirschl, RP, Pettrone, FA, Tennis elbow: the surgical treatment of lateral epicondylitis. J Bone Joint Surg 1979; 61-A:832–839. ![]()

82. Lamberts, H. De morbiditeitsanalyse-1972 door de groepspraktijk Ommoord: een nieuwe ordening van ziekte – en probleemgedrag voor de huisartsgeneeskunde. II. Huisarts Wet. 1975; 18:7.

83. Rodineau, J. L’Épicondylalgie ou ‘tennis elbow’. J Traumat Sport. 1988; 4:192.

84. Funk, DA, An, KN, Morrey, BF, Daube, JR, Electromyographic analysis of muscles across the elbow joint. J Orthop Res 1987; 5:529. ![]()

85. Nirschl, RP. Muscle and tendon trauma: tennis elbow tendinosis. In: Morrey BF, ed. The Elbow and its Disorders. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:523–535.

86. Cyriax, JH. Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, vol I. Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesion, 8th ed. London: Baillière Tindall; 1982.

87. Nirschl, RP, Pettrone, F, Tennis elbow: the surgical treatment of lateral epicondylitis. J Bone Joint Surg 1979; 61A:832. ![]()

88. Nirschl, RP. Lateral and medial epicondylitis. In: Morrey BF, ed. Master Techniques in Orthopedic Surgery: The Elbow. New York: Raven Press; 1994:129–148.

89. Kraushaar, B, Nirschl, R, Tendinosis of the elbow (tennis elbow): clinical features and findings of histological, immunohistochemical, and electron microscopy studies. J Bone Joint Surg 1999; 81A:259. ![]()

90. Regan, W, Wold, LE, Coonrad, R, Morrey, BF, Microscopic histopathology of lateral epicondylitis. Am J Sports Med 1992; 20:746. ![]()

91. Neviaser, TJ, Neviaser, RJ, Neviaser, JS, Ain, BR. Lateral epicondylitis: results of outpatient surgery and immediate motion. Contemp Orthop. 1985; 11:43.

92. Nirschl, RP, Prevention and treatment of elbow and shoulder injuries in the tennis player. Clin Sports Med 1998; 7:289. ![]()

93. Mens, JM, Stoeckart, R, Snijders, CJ, et al, Tennis elbow, natural course and relationship with physical activities: an inquiry among physicians. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1999;39(3):244–248. ![]()

94. Cyriax, J, Troisier, O, Hydrocortisone and soft-tissue lesions. BMJ 1952; ii:966. ![]()

95. Kerlan, RK, Glousman, RL, Injections and techniques in athletic medicine. Clin Sports Med. 1989;8(3):541–560. ![]()

96. Troisier, O, Les Tendinites épicondyliennes. Rev Prat. 1991;41(18):1651. ![]()

97. Hay, EM, Paterson, SM, Lewis, M, et al, Pragmatic randomised controlled trial of local corticosteroid injection and naproxen for treatment of lateral epicondylitis of elbow in primary care. BMJ. 1999;319(7215):964–968. ![]()

98. Assendelft, WJ, Hay, EM, Adshead, R, Bouter, LM, Corticosteroid injections for lateral epicondylitis: a systematic overview. Br J Gen Pract. 1996;46(405):209–216. ![]()

99. Verhaar, JA, Walenkamp, GH, van Mameren, H, et al, Local corticosteroid injection versus Cyriax-type physiotherapy for tennis elbow. J Bone Joint Surg. 1996;78B(1):128–132. ![]()

100. Smidt, N, van der Windt, DA, Assendelft, WJ, et al, Corticosteroid injections, physiotherapy, or a wait-and-see policy for lateral epicondylitis: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002; 359:657–662. ![]()

101. Tonks, JH, Pai, SK, Murali, SR, Steroid injection therapy is the best conservative treatment for lateral epicondylitis: a prospective randomised controlled trial. Int J Clin Pract 2007; 61:240–246. ![]()

102. Altay, T, Gunal, I, Ozturk, H, Local injection treatment for lateral epicondylitis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2002; 398:127–130. ![]()

103. Dogramaci, Y, Kalaci, A, Savaş, N, et al, Treatment of lateral epicondylitis using three different local injection modalities: a randomized prospective clinical trial. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129(10):1409–1414. ![]()

104. Mills, GP, Treatment of tennis elbow. BMJ 1928; i:12. ![]()

105. Mills, GP, Treatment of tennis elbow. BMJ 1937; ii:212. ![]()

106. Mennell, JM. Joint Pain – Diagnosis and Treatment using Manipulative Techniques. Boston: Little, Brown; 1964.

107. Stoddard, A, Manipulation of the elbow joint. Physiotherapy 1971; 57:259. ![]()

108. Kaltenborn, FM. Manual Therapy for the Extremity Joints, 2nd ed. Oslo: Olaf Norlis; 1976.

109. Kushner, S, Reid, DC, Manipulation in the treatment of tennis elbow. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1986;7(5):264. ![]()

110. Solveborn, SA, Radial epicondylalgia (‘tennis elbow’): treatment with stretching or forearm band. A prospective study with long-term follow-up including range-of-motion measurements. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1997;7(4):229–237. ![]()

111. Nagrale, AV, Herd, CR, Ganvir, S, Ramteke, G, Cyriax physiotherapy versus phonophoresis with supervised exercise in subjects with lateral epicondylalgia: a randomized clinical trial. J Man Manip Ther. 2009;17(3):171–178. ![]()

112. Gildenberg, PL, De Vaul, RA. Management of chronic pain refractory to specific therapy. In: Yomans JR, ed. Neurological Surgery. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1990:4144.

113. Zeisig, E, Ohberg, L, Alfredson, H, Sclerosing polidocanol injections in chronic painful tennis elbow-promising results in a pilot study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(11):1218–1224. ![]()

114. Scarpone, M, Rabago, DP, Zgierska, A, et al, The efficacy of prolotherapy for lateral epicondylosis: a pilot study. Clin J Sport Med. 2008;18(3):248–254. ![]()

115. Daubinet, G. L’Épicondylite rebelle: technique et protocol personnels de ténotomie des épicondyliens. J Traumatol Sport. 1988; 4:201.

116. Verhaar, J, Walenkamp, G, Kester, A, et al, Lateral extensor release for tennis elbow. J Bone Joint Surg. 1993;75A(7):1034–1043. ![]()

117. Dunkow, PD, Jatti, M, Muddu, BN, A comparison of open and percutaneous techniques in the surgical treatment of tennis elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(5):701–704. ![]()

118. Grundberg, AB, Dobson, JF, Percutaneous release of the common extensor origin for tennis elbow. Clin Orthop 2000; 376:137–140. ![]()

119. Baumgard, SH, Schwartz, DR, Percutaneous release of the epicondylar muscles for humeral epicondylitis. Am J Sports Med 1982; 10:233. ![]()

120. Yerger, B, Turner, T, Percutaneous extensor tenotomy for chronic tennis elbow: an office procedure. Orthopaedics 1985; 8:1261. ![]()

121. Oztuna, V, Milcan, A, Eskandari, MM, Kuyurtar, F, Percutaneous extensor tenotomy in patients with lateral epicondylitis resistant to conservative treatment. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2002;36(4):336–340. ![]()

122. Kaleli, T, Ozturk, C, Temiz, A, Tirelioglu, O, Surgical treatment of tennis elbow: percutaneous release of the common extensor origin. Acta Orthop Belg. 2004;70(2):131–133. ![]()

123. Dunkow, PD, Jatti, M, Muddu, BN, A comparison of open and percutaneous techniques in the surgical treatment of tennis elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(5):701–704. ![]()

124. Haupt, G, Use of extracorporeal shock waves in the treatment of pseudarthrosis, tendinopathy and other orthopedic diseases. J Urol. 1997;158(1):4–11. ![]()

125. Hammer, DS, Rupp, S, Ensslin, S, et al, Extracorporeal shock wave therapy in patients with tennis elbow and painful heel. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2000;120(5–6):304–307. ![]()

126. Krischek, O, Hopf, C, Nafe, B, Rompe, JD, Shock-wave therapy for tennis and golfer’s elbow – 1 year follow-up. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1999;119(1–2):62–66. ![]()

127. Spacca, G, Necozione, S, Cacchio, A, Radial shock wave therapy for lateral epicondylitis: a prospective randomised controlled single-blind study. Eura Medicophys 2005; 41:17–25. ![]()

128. Chung, B, Wiley, J, Effectiveness of extracorporeal shock wave therapy in the treatment of previously untreated lateral epicondylitis: a randomised controlled trial. Am J Sports Med 2004; 32:1660–1667. ![]()

129. Buchbinder, R, Green, SE, Youd, JM, et al. Shock wave therapy for lateral elbow pain. In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2006. Chichester: John Wiley; 2005.

130. Rovere, GD, Curl, WW, Browning, DG, Bracing and taping in an office sports medicine practice. Clin Sports Med. 1989;8(3):497. ![]()

131. Snyder-Mackler, L, Effects of standard and aircast tennis elbow band on integrated electromyography of forearm extensor musculature proximal to bands. Am J Sports Med 1989; 2:278. ![]()

132. Groppel, JL, Nirschl, RP, Pfantsch, E, Greer, N, A mechanical and electromyographical analysis of the effects of various joint counterforce braces on the tennis player. Am J Sports Med 1986; 14:195. ![]()

133. Wadsworth, CT, Nielsen, DH, Burns, LT, et al, The effect of the counterforce armband on wrist extension and grip strength and pain in subjects with tennis elbow. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1989; 11:192. ![]()

134. Savoie, F. Percutaneous release in the surgical treatment of lateral epicondylitis. Connecticut: New Haven; 1997.

135. Jafarian, FS, Demneh, ES, Tyson, SF, The immediate effect of orthotic management on grip strength of patients with lateral epicondylosis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39(6):484–489. ![]()

136. Baker, C, Cummings, P. Arthroscopic management of miscellaneous elbow disorders. Operative Techniques Sportsmed. 1998; 6:16.

137. Smidt, N, van der Windt, DA, Assendelft, WJ, et al, Corticosteroid injections, physiotherapy, or a wait-and-see policy for lateral epicondylitis: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9307):657–662. ![]()

138. Leach, RE, Miller, JK, Lateral and medial epicondylitis of the elbow. Clin Sports Med 1987; 659–672. ![]()

139. Ciccotti, MC, Schwaetz, MA, Ciccotti, MG, Diagnosis and treatment of medial epicondylitis of the elbow. Clin Sports Med 2004; 23:693–705. ![]()

140. Shiri, R, Viikari-Juntura, E, Varonen, H, Heliövaara, M, Prevalence and determinants of lateral and medial epicondylitis: a population study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(11):1065–1074. ![]()

141. O’Dwyer, KJ, Howie, CR, Medial epicondylitis of the elbow. Int Orthop. 1995;19(2):69–71. ![]()

142. Nirschl, RP, Pettrone, FA, Tennis elbow: the surgical treatment of lateral epicondylitis. J Bone Joint Surg 1979; 61-A:832–839. ![]()

143. Kurvers, HAJM, Verhaar, JAN. Golfelleboog of epicondylitis medialis, Verslag Nederlandse Orthopaedische Vereniging. Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1993; 137(23):1166.

144. Kurvers, H, Verhaar, J, The results of operative treatment of medial epicondylitis. J Bone Joint Surg 1995; 77A:1374. ![]()