Disorders of the breast

Introduction to breast disease

Virtually every woman with a breast lump, breast pain or discharge from the nipple fears she has cancer. The anxiety results from the unknown course of the disease, the threat of mutilation and the fear of dying. This has often prevented women from seeking medical advice, but publicity about self-examination and screening (see Ch. 6) and the potential benefits of early treatment has encouraged earlier presentation.

Rates of referral to breast clinics have increased, reflecting easier access, widespread breast screening and public awareness of breast cancer. Despite the fears of those referred, in the UK less than 15% prove to have cancer. The rest include benign breast conditions and others within the normal range of anatomy and physiology (see Box 45.1).

Symptoms and signs of breast disease

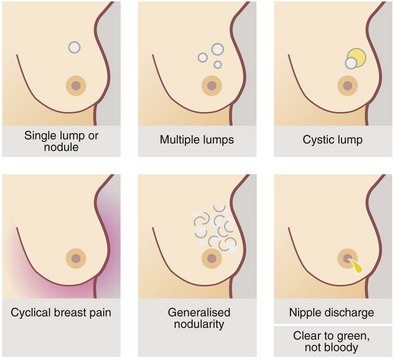

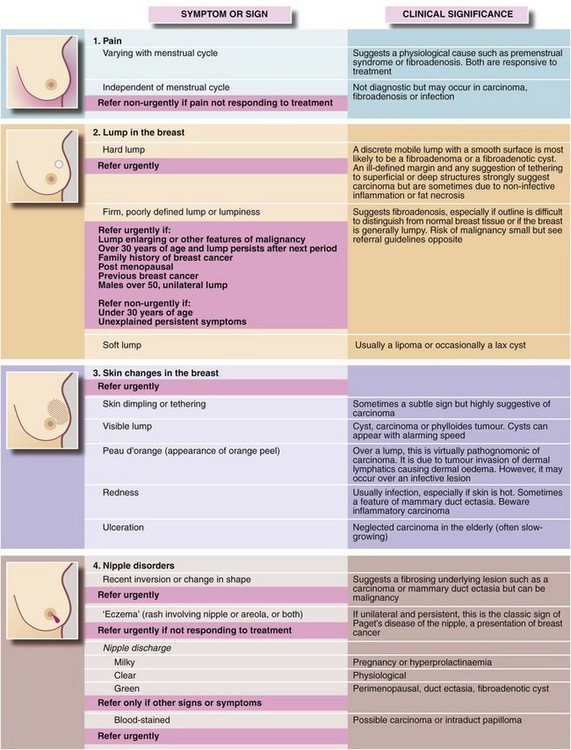

Patients may present with symptoms or signs (see Fig. 45.1). Two-thirds complain of a discrete lump or lumpiness.

Fig. 45.1 Symptoms and signs of breast disease (see also Figs 45.3 and 45.4)

UK NICE guidelines for urgent and non-urgent referral to a specialist are indicated on a pink background

Special points in history taking

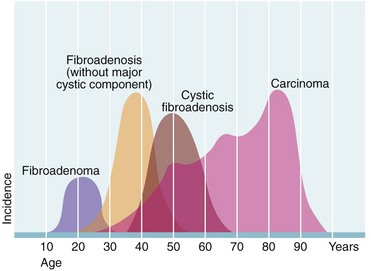

A detailed history can provide important clues to the pathology of a breast problem. Age alters the probability of different breast disorders (see Fig. 45.2); in particular, the risk of malignancy rises with age. The duration of symptoms should be established at the outset; cancers are usually slow-growing, whilst cysts can appear rapidly, sometimes almost overnight. Benign conditions such as fibroadenosis and fibroadenoma may present with lumps that fluctuate with the menstrual cycle or have decreased in size since first noticed. They are also more likely to be painful and tender than a malignant lesion.

A previous history of breast conditions, particularly malignancy, cysts or fibrocystic change, can be an indicator of the nature of a current breast problem. The greatest single risk factor for breast cancer is a previous history of the condition, however long ago (1% risk per year) (see Box 45.2). There is some evidence that patients with recurrent benign breast disorders are more liable to cancer.

Examination of the breasts

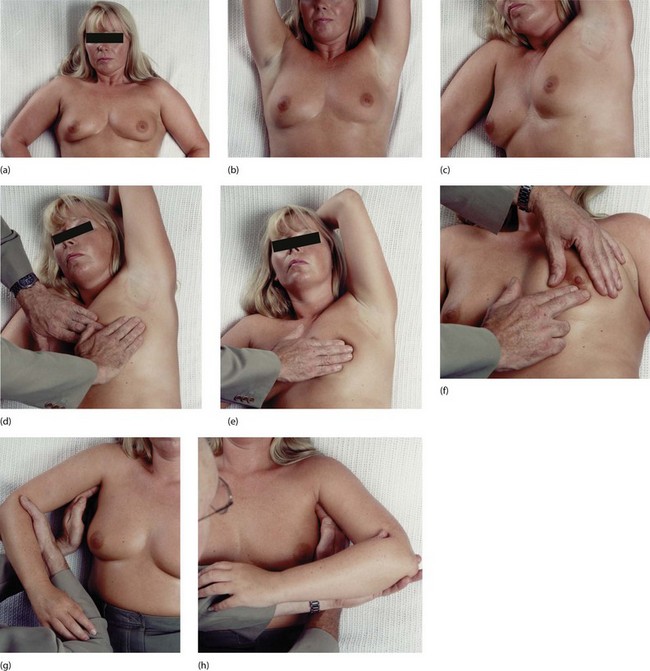

There are several accepted methods for examining the breasts; one is shown in Figure 45.3. All areas of the breast must be examined, with particular attention to the axillary tail and retro-areolar regions. Breast examination involves six distinct manoeuvres:

Fig. 45.3 Technique of breast examination

Inspection: the breasts should be inspected for asymmetry, skin tethering and dimpling and changes in colour. This should be performed with the patient sitting comfortably, pressing hands on hips (a), lifting arms in the air (b), and pressing hands on top of the head. Palpation: the patient should sit on an examination couch as shown in (c), with the backrest at about 45° and rolled slightly to the contralateral side. The arm on the side to be examined should be elevated and the head rested on the pillow. The effect of these manoeuvres is to spread the breast over a greater area of the chest wall. The flat of the right hand is used to palpate the breast circumferentially by quadrants (d)–(f). The central part of the breast and the axillary tail must also be palpated. If there is a history of nipple discharge, the areola is pressed in different areas (f) to identify the duct from which it emanates and therefore the segment involved. Finally the axillary lymph nodes are palpated as shown in (g) and (h). The left axilla is palpated with the right hand (h) and the right axilla is palpated with the left hand (g). It is important to relax the axillary muscles by supporting the weight of the patient’s arm as shown. The fingers of the examining hand are firmly held in a curve, pressed high into the apex of the axilla against the chest wall and drawn downwards. The hand will then ‘ride over’ any enlarged axillary nodes

• Observation with the patient sitting up

• Observation with the patient raising and lowering her arms

• Systematic palpation of each breast

During inspection, the signs to be looked for are listed in Figure 45.1.

Palpation may be done circumferentially using the flat of one hand, starting at the nipple then moving in progressively larger circles; radially from the nipple outwards like the spokes of a wheel; or by sectors, examining each quadrant in turn. Axillary lymph nodes are palpated whilst the examiner’s other hand supports the patient’s arm (Fig. 45.3g, h). This helps relax the muscles and aids assessment of the nodal groups (medial, lateral, anterior, posterior and apical). Note that clinical assessment of axillary nodes is unreliable, with a 30% false positive and a 30% false negative rate.

Lumps: The differential diagnosis of a discrete breast mass is:

During the examination the patient needs to point out any lump she is worried about. The normal breast has a wide range of textures, from soft through nodular to hard, so the texture of the rest of the breast must be taken into account. When a lump is found, its characteristics should be defined (see Box 45.3), in particular whether it is discrete or dominant or whether it is an area of nodularity or ‘thickening’. If there is a discrete mass, does it appear benign or suspicious for malignancy? (Characteristic signs of cancer are shown in Fig. 45.4.) Note that even for breast specialists, clinical examination has a low sensitivity (i.e. ability to detect real abnormalities) of 65–80%. In one clinical evaluation system, increasing levels of suspicion are graded E1 to E5; an E3 designation may prompt a core biopsy even if radiological findings are not suspicious. Only 3% of breast cancers occur under the age of 30 but a discrete lump in a patient over 65 is a cancer until proved otherwise.

Investigation of breast disorders

Imaging

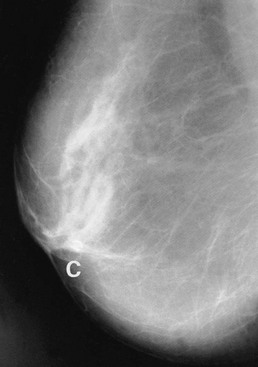

Features looked for on a mammogram include:

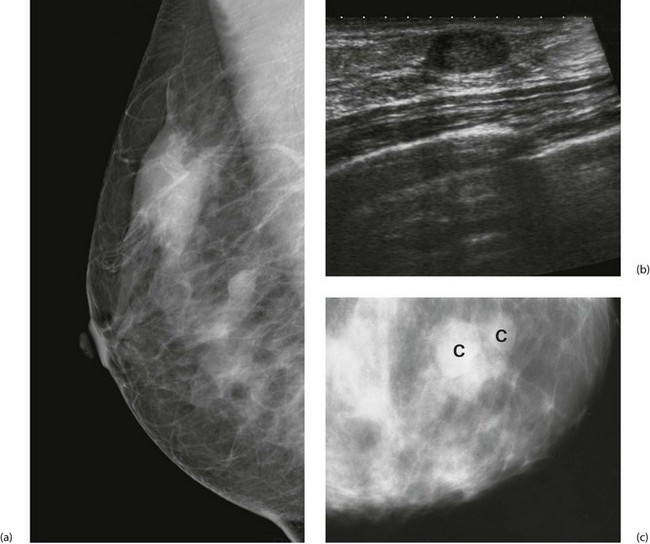

A typical carcinoma appears as a spiculated mass lesion (dense centre with radiating lines) which may have malignant-type fine linear or granular microcalcification (Fig. 45.5). Fine granular microcalcification within a spiculate lesion is virtually pathognomonic of cancer. Tumours as small as 2–3 mm are sometimes detectable radiologically, long before they become palpable.

Benign-type microcalcification is coarse and ‘chunky’ (Fig. 45.6). Fine branching microcalcification is characteristic of ductal carcinoma-in-situ (DCIS). Architectural distortion and asymmetry are subtle radiological signs but should be viewed with suspicion.

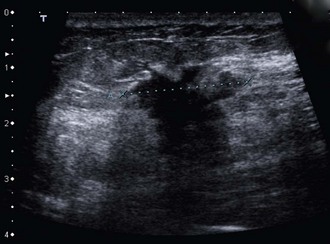

Ultrasound has long been used to distinguish solid lesions from cysts and has a specificity of 100% for this. Modern B-mode ultrasound demonstrates breast anatomy in great detail and is complementary to mammography. Benign lesions can be distinguished from malignancy with a sensitivity for cancer of at least 85%. Ultrasound can accurately measure the size of a cancer (Fig. 45.7) and can guide percutaneous needle biopsies and cyst aspiration (Fig. 45.8).

Biopsy

Most palpable and all non-palpable image-detected masses are biopsied under image guidance, as are suspicious areas of calcification. Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) specimens are rarely used for tissue diagnosis now (see Box 45.4). FNAC has a sensitivity of 95% for detecting malignancy but cannot distinguish between in situ and invasive cancers. By contrast, core biopsy has a sensitivity of 98%. The tissue architecture is preserved so that invasion can be confidently diagnosed on histology and tumours can be pathologically graded. After core biopsy patients need to return later for the results as the pathology has to be read after the specimen has been fixed. This has the advantage that any bad news can be broken in a phased manner. If needle biopsy is negative or equivocal, a discrete lump should be completely excised with a wide margin of apparently normal breast tissue and the specimen examined histologically. This procedure, excision biopsy, can also form the first step in controlling local disease.

Breast cancer

Risk factors

Age: Age is the greatest risk factor. Incidence rates rise from about 25, more steeply between 40 and 55, with a slight levelling off until about 70. After that, another fairly steep rise continues into old age (see Fig. 45.2). Breast cancer is the commonest cause of death in women aged between 40 and 50 years.

Genetic factors: The aetiology of breast cancer is multifactorial, with genetic factors being relatively more important in premenopausal women and environmental factors more so after the menopause. These play a small role in calculating the risk of breast cancer, but the risk is greater in women with a strong family history (two first-degree relatives, bilateral breast cancer or diagnosis before the age of 50). Such a family history accounts for 10% of cancers, with half due to genetic mutations, mainly BRCA1 (17q21) and BRCA2 (13q41) genes which are transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion. A mutation in either of these leads to an 80–90% lifetime risk of developing the disease. The same mutations are also linked to ovarian cancers. Women with a BRCA mutation should be counselled about their individual risk of breast and ovarian cancer and the treatment options (ranging from surveillance to risk-reducing bilateral mastectomies, which reduce the cancer risk by more than 90% and oophorectomy).

Hormonal factors: Growth of most breast cancers is promoted by oestrogens, hence reproductive physiology and behaviour influence cancer risk. It has long been known that nulliparous women are at greater risk: Ramazzini commented in 1703 that breast cancer was common in Catholic nuns who as ‘Vestalis Virgines’ were prone to ‘horrendis mammarium canceris’.

Social and geographic factors: Breast cancer is more common in the Western world and in women in higher socioeconomic classes. Obese women are at a higher risk, possibly due to conversion of androgens to oestrogen in adipose tissue. Consuming more than 3 units of alcohol a day increases the risk by 50%.

Epidemiology

Environmental factors: Exposure to irradiation in the teenage years may initiate some breast cancers which are then promoted by other factors years later. Female survivors of the atomic bombs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have a high risk of developing breast cancer, as do those who have received mantle irradiation for Hodgkin’s disease. Surprisingly, no link has been shown between smoking and breast cancer.

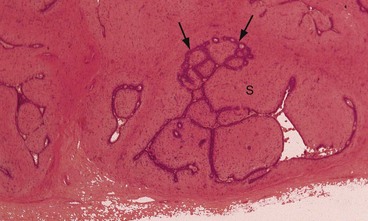

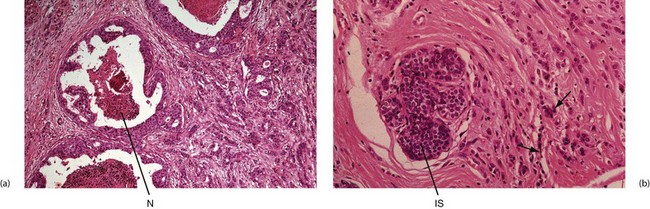

Pathology

Tumour types: Almost all breast cancers are adenocarcinomas and arise from the terminal duct/lobular unit. Over 85% originate from the ductal component and are designated invasive ductal carcinomas of ‘no special type’ (NST) (Fig. 45.9). About 8% arise from the lobules and are known as lobular carcinomas. These are similar in behaviour and prognosis to ductal carcinomas but can be difficult to see on mammography and often present late. Microscopically these tumours are characterised by linear arrangements of cells, so-called ‘Indian filing’ (Fig. 45.9b). A few invasive carcinomas have ductal and lobular features and are termed ‘mixed’ tumours.

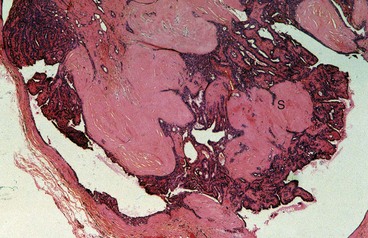

Fig. 45.9 Breast adenocarcinoma—histopathology

(a) Ducts to the left of the picture contain highly atypical epithelium, with central necrosis N, a type of in situ ductal carcinoma also known as comedocarcinoma. On the right of this micrograph is invasive ductal carcinoma composed of many small glandular structures diffusely invading breast tissue. (b) In situ IS and invasive lobular carcinoma. Malignant cells tend to be less atypical than in ductal carcinoma and do not form glands, but often invade in ‘single-file’ (arrowed). Intracellular mucin is also characteristic of this variant of breast carcinoma

In situ carcinoma: Breast cancers can develop from an in situ or non-invasive precursor known as ductal carcinoma-in-situ or DCIS. These are primarily detected through breast screening programmes as suspicious microcalcifications. Post-mortem studies suggest there is only a 20% chance of DCIS progressing to invasive cancer. DCIS ranges from low to high grade, and higher-grade lesions are more likely to progress if untreated.

Paget’s disease of the nipple: In Paget’s disease, the epidermis becomes infiltrated by neoplastic cells arising from an underlying ductal carcinoma. These reach the surface by intra-epithelial spread along mammary ducts (Fig 45.10).

Inflammatory carcinoma: Inflammatory carcinoma may be difficult to distinguish from infective conditions of the breast. It often develops without a palpable mass, and can be misdiagnosed as cellulitis. It should be suspected in older women with inflammation that does not respond to antibiotics. Mammogaphy and ultrasound are helpful in establishing the diagnosis although appearances can be similar as a breast abscess often contains necrotic debris simulating a solid mass on imaging. Chronic mastitis during pregnancy may mask an underlying inflammatory carcinoma and delay diagnosis.

Tumour grade: Breast carcinomas are graded histologically I–III according to degree of differentiation. Higher grade tumours tend to infiltrate blood and lymphatic vessels which increases the chance of lymph node and haematogenous metastases, and thus have a worse prognosis. Unfortunately, grade III tumours are more common in premenopausal women. Also, the larger the tumour, the worse the grade tends to be.

Natural history of breast cancer

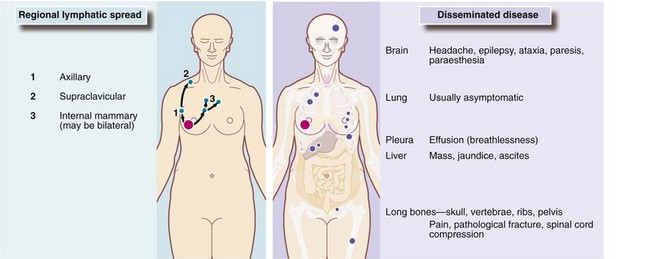

There are two main theories about the biological dissemination of breast cancer. Halsted proposed in the 1880s that cancer spreads sequentially from a focus in the breast to regional lymph nodes and then into the bloodstream to produce haematogenous metastases. Thus, distant spread occurs only after lymph nodes have been invaded and their filtration capacity overwhelmed. On this basis, loco-regional control by radical mastectomy and/or radiotherapy would cure most patients. By contrast, Bernard Fisher’s research between 1957 and 1970 challenged Halsted’s concept (which mandated radical surgery) with evidence that breast cancer might already be systemic long before the primary is detectable. Furthermore, disseminated cancer cells could potentially metastasise throughout life and it is these that ultimately determine the patient’s fate (Fig. 45.11).

Principles of management of breast cancer (Boxes 45.5 and 45.6)

Staging

Once a diagnosis of cancer has been made, the disease should be staged to define the extent of spread. Staging begins with triple assessment of the breast and axilla (see above, p. 546). If there is no evidence of axillary nodal or distant involvement and the cancer is amenable to surgery, no further investigations are performed. Clinical signs that may preclude initial surgery are peau d’orange and inflammatory cancer, fixation to the chest wall and distant metastatic disease. These may be indications for neoadjuvant chemotherapy, i.e. in advance of surgery.

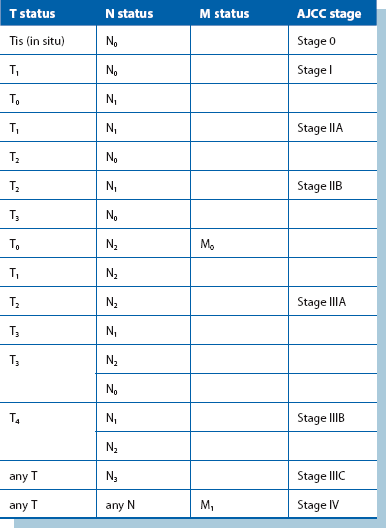

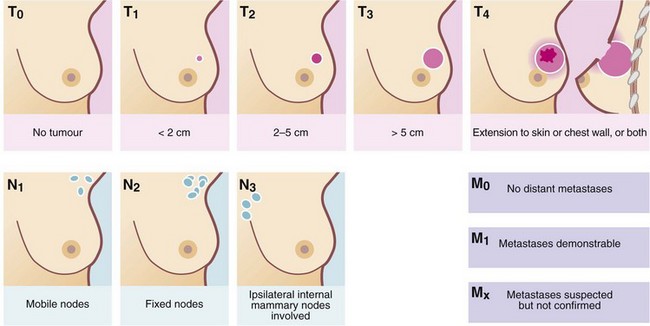

Prognostic status

The TNM system (Fig. 45.12 and Table 45.1) classifies cancer according to the size of the primary Tumour, the pathological Nodal status and the presence or absence of distant Metastases. TNM grading is used to stage breast patients into four categories (see Table 45.1) and this correlates well with observed rates of disease-free survival at 5 years: 84% for stage I, 72% for stage II, 47% for stage III and 18% for stage IIIC tumours. For further details, see http://poptop.hypermart.net/brcastg.html. In addition to this traditional staging system, the Nottingham Prognostic Index (see http://nuhrise.org/2010/11/nottingham-prognostic-index-plus-npi-a-ground-breaking-tool-for-breast-cancer/) is widely used, which grades patients into six prognostic groups, based on tumour size, nodal status and histological grade.

Loco-regional treatment

Breast conservation surgery

Selection criteria for conservative surgery are shown in Box 45.7. Wide local excision aims to remove the tumour with a 1 cm macroscopic margin of normal breast tissue. Skin is not usually excised unless there is tethering. It is possible to remove up to 20% of the breast volume and still achieve a reasonable cosmetic result. For impalpable tumours, excision can be directed by ultrasound-guided skin marking over the cancer or insertion of a hooked wire under mammography. A quadrantectomy is sometimes performed, which removes the tumour within a quadrant-shaped resection. However, this yields a poor cosmetic result.

Reconstructive surgery

The second option to recreate the breast is to employ a myocutaneous flap, using skin, fat and muscle (if necessary). Tissue can be taken from the abdominal wall (‘TRAM’—transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap, or ‘DIEP’—deep inferior epigastric perforator flap), or from the back (‘LD’—latissimus dorsi flap) or from the buttock and inner thigh (Fig. 45.13). All of these can be augmented by implants. Tissue transfer produces a more natural-feeling and moving breast, but the operation takes a lot longer and there is substantial donor site morbidity. Most patients need additional procedures to augment or reduce the contralateral breast for symmetry and to create a new nipple. Immediate reconstruction aims to improve psychological well-being, but the effects of postoperative radiotherapy on the implant and reconstruction must be considered. Sometimes reconstruction is delayed due to the need for adjuvant chemo-radiotherapy, where wound healing problems could delay the treatment.

Fig. 45.13 Breast reconstruction following skin-sparing mastectomy using latissimus dorsi flap and silicone implant

Via a circumareolar incision, the entire breast tissue including the nipple–areolar complex is excised and the axillary node dissection performed. The latissimus dorsi muscle is mobilised as a pedicle flap together with an ellipse of overlying skin and tunnelled anteriorly to lie in the breast cavity. Excess skin is trimmed from the flap to leave a circular disc to replace the excised nipple. A silicone implant is sandwiched between the latissimus dorsi and pectoralis muscles to provide bulk and reshape the breast

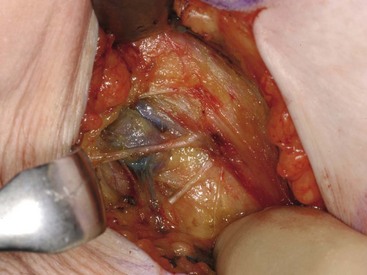

Axillary surgery

Sentinel node biopsy: Lymphatic spread nearly always follows a predictable pattern, with a sentinel node the first to be affected, so the standard diagnostic procedure is now sentinel lymph node biopsy (Fig. 45.14). This node is identified using both a radioactive isotope bound to albumin, injected next to the tumour 12 hours before surgery, and a blue dye injected into the periareolar area at the start of surgery. Radioactivity is detected at surgery and the visibly blue nodes are excised and examined by the pathologist. This can be done by immediate frozen section, and if the nodes are positive, an axillary clearance can be completed.

Fig. 45.14 Sentinel node biopsy

The sentinel node is usually the first axillary node to receive lymphatic drainage from the tumour. Before operation, a blue dye and a radiotracer are injected into subareolar area and at operation the sentinel node is identified visually and by using a device to detect radioactivity

Axillary clearance: Axillary surgery is performed both to fully stage the axilla and to treat proven axillary disease to improve local control and prevent recurrence. However, the indications for, and the extent of axillary surgery remain controversial. If axillary surgery is indicated, techniques need to keep the morbidity low to minimise lymphoedema and reduced shoulder function.

Adjuvant systemic treatment

The low cure rate for apparently early breast cancer is due to occult metastatic spread. The aim of systemic therapy is to delay or prevent these metastases. Some form of prognostic index is often used for planning systemic therapy (see Table 45.3, p. 558), although these are more reliable for predicting short-term than long-term survival. Patients in the best prognostic group are unlikely to have micrometastases and do not generally require systemic treatment. For the rest, the choice of adjuvant therapies (or none) often involves detailed discussion between patient and doctor about the balance of benefit and side-effects. Table 45.2 summarises current thinking about adjuvant systemic therapies for different categories of patient. An American web-based system called Adjuvantonline (www.adjuvantonline.com) is widely used internationally to estimate the benefits and side-effects of different therapies in individual patients and the likely risk of cancer-related mortality or relapse without adjuvant therapy. Data are entered about the patient and their cancer (e.g. age, tumour size, nodal involvement, histological grade) and estimates are then printed as graphs and texts to inform consultations.

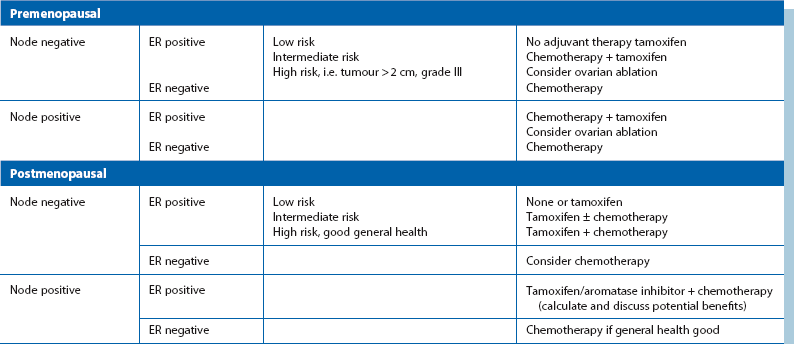

Table 45.2

Criteria for selection of adjuvant therapies*

*Low, intermediate and high risk refer to the chances of developing distant disease and relapse and are based on the criteria of tumour size, histological grade and nodal status

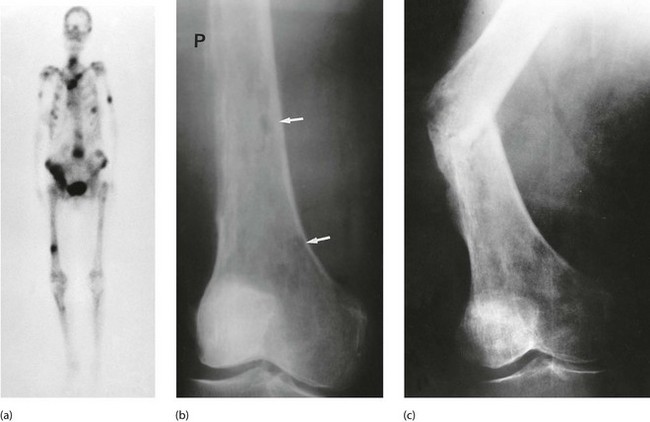

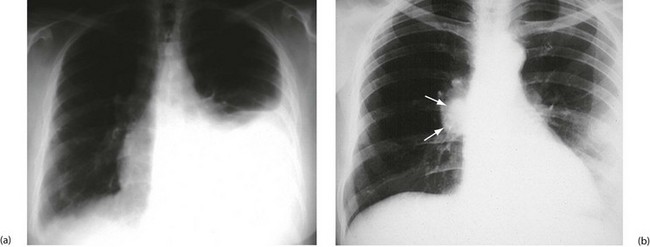

Control of advanced and disseminated disease (Figs 45.15–45.18)

About two-thirds of breast cancer patients now survive for at least 20 years, but many eventually succumb from micrometastatic disease which later progresses to clinically evident metastases. Once metastases have appeared, treatment is palliative, but very worthwhile prolongation of life and improved quality of life can often be achieved. The commonest sites for metastases are bones, liver, lung and brain. Bone metastases are more likely in postmenopausal women with well-differentiated, ER-positive tumours. More than 90% of patients with metastatic disease have bone lesions. These are usually lytic and commonly affect ribs and vertebrae. They are very painful and can lead to pathological fractures (Fig. 45.17). Luckily, they often respond to palliative radiotherapy. Lobular carcinoma can metastasise to unusual sites such as skin (Fig. 45.18) and gastrointestinal tract.

Fig. 45.15 Advanced breast cancer

This 60-year-old woman had been aware of a lump in her right breast for over a year before she could be persuaded to seek treatment. The whole breast is involved and malignancy has spread through the skin widely across the chest wall. Palliative treatment was given with radiotherapy and tamoxifen

Fig. 45.18 Skin secondaries following simple mastectomy and radiotherapy

This patient presented with painless, slightly elevated nodules in the skin below the axilla 3 years after treatment for lobular carcinoma of the breast. In this photograph, the arm is elevated and one skin secondary can just be made out (arrowed); the site of excision biopsy of another is seen at B

Locally advanced breast cancer (stage III disease) often involves most of the breast tissue (see Fig. 45.15). The skin becomes infiltrated (peau d’orange or inflammatory cancer where dermal lymphatics are involved), and eventually ulcerates; the tumour can invade the chest wall. Ultimately much of the chest wall may become involved, when it is known as carcinoma en cuirasse. Locally advanced disease of breast and axilla may initially be inoperable but neoadjuvant hormonal or chemotherapy can downsize the cancer so a toilet mastectomy can be performed. Radiotherapy alone can be employed for palliation of advanced skin, breast, chest wall and lymph node disease.

Stage IV (metastatic cancer) typically presents in younger women with poorly differentiated tumours that have spread to viscera. Recurrent pleural effusions result from pulmonary metastases (Fig. 45.16) and are managed with aspiration or pleurodesis (obliterating the pleural cavity by instilling tetracycline or bleomycin) or performing surgical pleurectomy. Ascites occurs secondary to liver involvement, and patients can present with nausea, anorexia, weight loss and jaundice. Lymphangitis carcinomatosa (widespread dissemination in skin or lung lymphatics) and fulminant liver metastases may occur in the terminal stage of the disease. Brain metastases can present with headaches and neurological symptoms due to a rise in intracranial pressure.

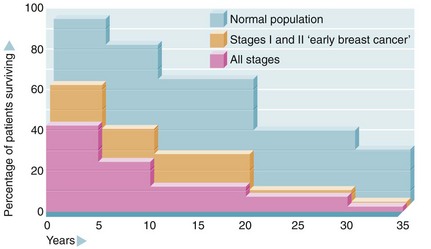

Life expectancy and prognosis

When long-term survival curves have been examined statistically, there is no evidence of ‘cure’ in the normally accepted sense (Fig. 45.19), although a ‘personal cure’ is achieved in about 50% of patients who die from some other disease. Micrometastatic foci can remain dormant for 35 years or more and become ‘kick started’ for unknown reasons into progressive metastatic disease and death. Loco-regional relapse often occurs within the first 5 years, but distant disease tends to occur much later.

Fig. 45.19 Life expectancy after diagnosis of breast cancer (after Brinkley and Haybittle)

Note that 5- and 10-year survival has improved in recent years as a result of better diagnosis and treatment but it is uncertain that long-term survival will also improve

Breast cancer survival estimates from prognostic scoring systems are meaningful only for about 10 years, and as estimates are based on group analyses, they are of doubtful relevance for any individual. A commonly used tool is the Nottingham Prognostic Index (NPI), which divides patients into five prognostic groups (see Table 45.3). Adjuvantonline is also popular for estimating prognosis.

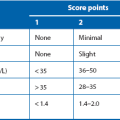

Table 45.3

Nottingham Prognostic Index (NPI) for breast cancer*

| Nottingham prognostic group | NPI score | Estimated 10-year survival |

| Excellent | ≤ 2.4 | 95% |

| Good | ≤ 3.4 | 83% |

| Moderate I | ≤ 4.4 | 70% |

| Moderate II | < 5.4 | 51% |

| Poor | > 5.4 | 19% |

*The NPI is calculated as follows: 0.2 × tumour size in cm + histological grade + lymph node status (node negative scores 1; one to three positive nodes scores 2, and four or more positive nodes scores 3)

Benign breast disorders

Abnormalities of normal development and involution (ANDI)

Clinical presentation and management

Fibrocystic change (fibroadenosis) presents as either a single lump or areas of lumpiness which are painful and tender premenstrually, i.e. cyclically (see Fig. 45.20). These changes may be difficult to distinguish clinically from carcinoma, and florid fibrocystic change can mask a cancer both clinically and radiologically. Fibrocystic change is most common between the ages of 35 and 45 years.

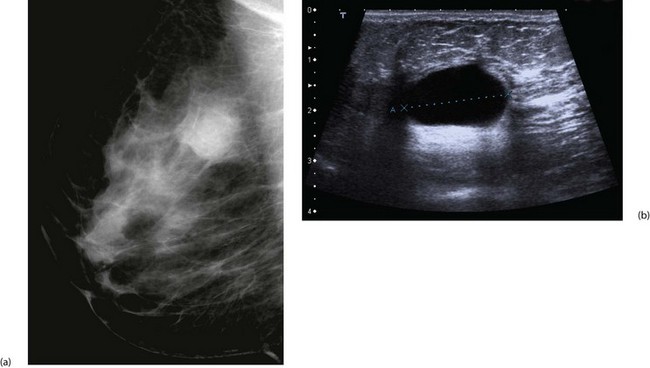

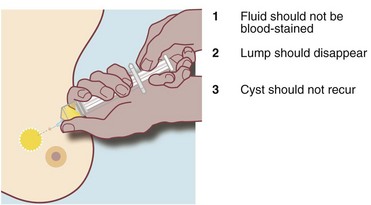

Cyst formation is more prevalent over the age of 40 years and in perimenopausal women. Cysts may present symptomatically as single or occasionally multiple lumps. Cysts develop from lobules and are fluid-filled spaces. Microcysts are part of the involutionary process and may coalesce to produce a larger cyst which presents as a smooth, round palpable lump. Larger cysts may be tense, tender and fluctuant with the texture of a table tennis ball. Cysts can usually be diagnosed clinically and are readily confirmed with ultrasonography; they are usually recognisable on a mammogram. Simple cysts can be aspirated under ultrasound control or freehand. Provided the cyst fluid is not blood-stained, there is no residual lump post aspiration and there are no sonographically suspicious features, patients can be discharged without further follow-up, although cysts can recur or new cysts develop (see Fig. 45.21). Cysts are uncommon over the age of 60 years unless the patient is taking HRT. Under these circumstances it is important to exclude an intracystic papilloma, intracystic carcinoma or a cystic carcinoma.

Fibroadenoma

Fibroadenoma is a localised form of ANDI rather than a benign tumour. This lesion arises from a single lobule and is composed of epithelial and fibrous components (Fig. 45.22). Fibroadenomas undergo involution in the perimenopausal years but can persist into old age and become calcified.

Duct papilloma

Intraduct papillomas are localised areas of epithelial proliferation. They are villous lesions composed of a fibrovascular core covered by a double layer of epithelium. They usually occur as solitary lesions in the main lactiferous ducts close to the nipple but multiple papillomas can occur more peripherally. Papillomas are not premalignant (see Fig. 45.23). They present as spontaneous blood-stained or clear watery nipple discharge, often from a single duct; a retroareolar mass may be palpable. These lesions are best imaged with ultrasound and the diagnosis confirmed on core biopsy. Papillomas are treated by excision of the affected duct (microdochectomy) or a group of ducts (wedge resection). If the causative lesion cannot be found at operation, a subareolar excision of all the ducts may be necessary.

Infections of the breast

Breast infection is occasionally seen in neonates, but is commonest in premenopausal women. Lactational mastitis usually occurs during the first 3 months of breast feeding and can lead to septicaemia. Risk factors include a cracked nipple and poor feeding technique causing milk stasis. The organism responsible is almost always Staph. aureus. Patients present with pain, swelling and erythema. Treatment is with empirical antibiotics (such as flucloxacillin), together with continued feeding or milk expression. If the patient is septic, she may need intravenous antibiotics. If an abscess develops (see Fig. 45.24), this should be drained with repeated ultrasound-guided aspiration until resolution. Surgery is only indicated if the skin is threatened or necrotic. In this case, a small stab incision is made, and the abscess cavity is flushed until all the pus is drained.

Duct ectasia

Mammary duct ectasia refers to dilatation and shortening of the major lactiferous ducts. It is a common involutional change appearing around the menopause. It presents with spontaneous cream, yellow or green nipple discharge, a palpable subareolar mass or nipple inversion. Plasma cells are a characteristic feature on histology; this may be described as plasma cell mastitis. Ducts can calcify and be seen on a mammogram (Fig. 45.25). Duct ectasia should be managed conservatively, unless radiological findings are suspicious for malignancy. Persistent discharge can be treated by subtotal or total nipple duct excision.

Male breast disorders

The two main breast conditions in males are gynaecomastia and cancer.

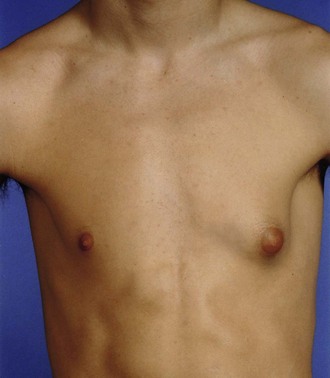

Gynaecomastia (Fig. 45.26)

Gynaecomastia is a benign proliferation of the male breast which feels like a rubbery firm mass extending concentrically from the nipple. It results from an imbalance of oestrogens and androgens acting on the breast. Primary gynaecomastia is physiological and occurs in three phases: infantile gynaecomastia is present at birth in response to oestrogens crossing the placenta and resolves spontaneously over several weeks. In puberty, the condition is bilateral in 50–60%; the exact mechanism is unknown but most resolve spontaneously. Senescent gynaecomastia peaks at 50–69 years of age and is more likely in obese men.

Secondary gynaecomastia is either due to medication or pathological:

• Medication—drugs include spironolactone, digoxin, ranitidine, calcium channel blockers, together with anabolic steroids and cannabis use. Hormonal treatment for prostate cancer can also cause gynaecomastia

• Pathological—alcoholic cirrhosis interferes with the metabolism of oestrogens and decreases free testosterone and some testicular germ cell tumours may secrete oestrogens. Other predisposing illnesses include chronic renal failure, diabetes and hypogonadism

Adults with gynaecomastia should undergo triple assessment and have blood tested for prolactin, LH, oestrogen, testosterone and hCG to exclude hypogonadism and testicular tumours. Most men can then be reassured without treatment. Surgery is usually performed in younger males for cosmetic purposes.