Disorders of puberty

1. What physiologic events initiate puberty?

Reactivation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis initiates puberty. Several neurotransmitters, including kisspeptin, stimulate the hypothalamic secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) in pulses during sleep and eventually during waking hours as well. GnRH pulses stimulate the pituitary gland to secrete pulses of gonadotropins, luteinizing hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), of which there is an LH predominance. In response to the increased secretion of gonadotropins, increased secretion of gonadal hormones leads to the progressive development of secondary sexual characteristics and gametogenesis. In both sexes, puberty requires maturation of gonadal function and increased secretion of adrenal androgens.

2. How is pubertal development measured?

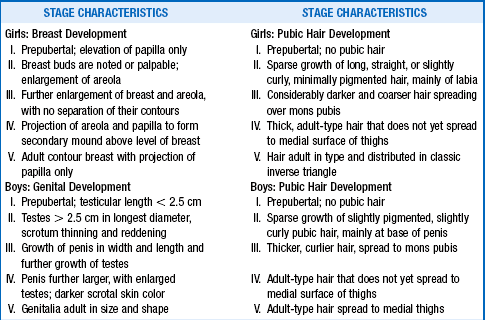

Sexual maturity is determined by physical examination and is described in a scale devised by John Tanner in 1969 (Table 43-1). Because of the distinct actions of adrenal androgens and gonadal steroids, it is important to distinguish between pubic hair and breast development in girls and between pubic hair and testicular development in boys. In all cases, Tanner stage I is prepubertal and Tanner stage V is complete maturation. In addition to the physical examination, the tools to assess pubertal development may include determination of bone age, growth velocity, growth pattern, and specific endocrine studies.

TABLE 43-1.

TANNER STAGES OF PUBERTAL DEVELOPMENT

Data from Marshall WE, Tanner JM: Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child 44:291–303, 1969; Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys. Arch Dis Child 45:13–23, 1970.

Adrenarche refers to the time during puberty when the adrenal glands increase their production and secretion of adrenal androgens. Plasma concentrations of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA-sulfate (DHEA-S), the most important adrenal androgens, begin to increase in children by approximately 6 to 8 years. However, the signs of adrenarche, such as pubic hair, axillary hair, acne, and body odor do not typically occur until early puberty to midpuberty. The control of adrenal androgen secretion is not clearly understood, but it appears to be separate from GnRH and the gonadotropins.

4. What controls the pubertal growth spurt?

In both boys and girls, the pubertal growth spurt is primarily controlled by the gonadal steroid estrogen. In both sexes, gonadal (and adrenal) androgens are aromatized to estrogens. Estrogens augment growth hormone (GH) and insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) secretion. Estrogens also suppress osteoclast activity and prolong the life span of osteoblasts and osteocytes. Androgens have a small independent role in maintenance of adequate bone mineral density. At the end of puberty, linear growth is nearly complete as a result of the effects of gonadal steroids on skeletal maturation and epiphyseal fusion.

5. What is the normal pattern of puberty in boys?

The mean age of puberty onset in boys is 11.8 years, with a range of 9 to 14 years. Black boys may start puberty as early as 8 years of age. The first evidence of puberty in the majority of boys is enlargement of the testes to a volume greater than 4 mL or a length greater than 2.5 cm. It is not until midpuberty, when testosterone levels are rapidly rising, that boys experience voice change, axillary hair, facial hair, and the peak growth spurt. Spermatogenesis is mature at a mean age of 13.3 years.

6. What is the normal pattern of puberty in girls?

Girls normally begin puberty between age 8 and 13 years (mean age: 10.4 years for white girls, 9.8 years for Hispanic girls, and 9.5 years for black girls). The initial pubertal event is typically the appearance of breast buds, although a small percentage of girls will develop pubic hair first. In an even smaller percentage of girls, menstrual cycling may appear first. Initial breast development often occurs asymmetrically and should not be of concern. Breast development is primarily under the control of estrogens secreted by the ovaries, whereas growth of pubic hair and axillary hair results mainly from adrenal androgens. Unlike in boys, the pubertal growth spurt in girls occurs at the onset of puberty. Menarche usually occurs 18 to 24 months after the onset of breast development (mean age: 12.5 years). Although most girls have reached about 97.5% of their maximum height potential at menarche, this can vary considerably. Consequently, age of menarche is not necessarily a good predictor of final adult height.

7. What constitutes sexual precocity in boys and girls?

Precocious puberty is defined as pubertal development occurring below the limits of age set for normal onset of puberty. In girls, this is puberty before 8 years in white girls, 6.6 years in black girls, and 6.8 years in Hispanic girls. For boys, precocious puberty is development occurring before 9 years in white and Hispanic boys and 8 years in black boys. Girls showing signs of puberty between 6 and 8 years often have a benign, slowly progressing form that requires no intervention. Consequently, evaluation and treatment of girls who start puberty between 6 and 8 years should depend on factors such as family history, rapidity of development, the presence of central nervous system (CNS) symptoms, and family concern. Girls who are short and start puberty between 6 and 8 years may also benefit from evaluation. In children who present with early pubertal signs, precocious puberty must be distinguished from normal variants of puberty, such as benign premature thelarche and benign premature adrenarche.

8. Which two common benign conditions in girls are often confused with precocious puberty?

Benign premature thelarche is defined as isolated breast development in girls without other signs of puberty such as linear growth acceleration and signs of adrenarche, such as pubic hair, axillary hair, body odor, and acne. Benign premature adrenarche, which occurs in both sexes, is defined as the early development of pubic hair with or without axillary hair, body odor, and acne. There are no signs of gonadarche in benign premature adrenarche; girls have no breast development, and boys have no testicular enlargement.

9. How is benign premature thelarche diagnosed?

Several characteristics of benign premature thelarche distinguish it from the breast development that occurs in precocious puberty. First of all, benign premature thelarche is most common in girls who are either less than 2 years old or between 6 and 8 years of age. Girls with benign premature thelarche may have a history of slowly progressing breast development or waxing and waning of breast size. Growth rate and bone age are not accelerated, and on physical examination, the breast tissue rarely develops beyond Tanner stage II or III. GnRH stimulation may provoke an FSH-predominant response, as opposed to the typical LH-predominant response seen in true central puberty.

10. How is benign premature thelarche treated?

The natural course of benign premature thelarche is for the breast tissue to regress or fail to progress. Because of the benign nature of this condition, treatment is not necessary except for reassurance and follow-up. Follow-up is critical because premature thelarche occasionally is the first sign of what later becomes apparent as central precocious puberty. Measurement of breast tissue diameter during the clinic visit can be helpful for comparison at a later visit.

11. How is benign premature adrenarche diagnosed?

Benign premature adrenarche is caused by early secretion of the adrenal androgens, primarily DHEA and DHEA-S, and is suspected when clinical signs of androgen exposure are present, such as pubic hair, axillary hair, acne, or body odor. A child who has benign premature adrenarche and Tanner stage II pubic hair development will have adrenal androgen values similar to those normally found in a pubertal child at the same stage of development. As in premature thelarche, growth rate and bone age are typically not accelerated. If signs of puberty are rapidly progressing, or if there is evidence of increased linear growth and advanced bone age, measurement of androgens (DHEA-S, androstenedione, and testosterone) is performed to evaluate for a serious virilizing disorder such as congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) or an adrenal tumor. A 17-hydroxyprogesterone (17-OHP) level may also be drawn as the first screen for late-onset CAH.

12. How is benign premature adrenarche treated?

The natural course of benign premature adrenarche is a slow progression of the signs of adrenarche with no effect on the timing of true puberty. Because pubic hair development may be the first sign of puberty, follow-up is necessary to evaluate for evidence of gonadarche (i.e., breast development or testicular enlargement).

13. What clinical findings are associated with precocious puberty?

Precocious puberty, regardless of the cause, is associated with accelerated linear growth and skeletal maturation secondary to elevated sex steroid levels. Children with precocious puberty are often tall for their age during childhood. However, skeletal maturation may become more advanced than stature, thus leading to premature fusion of the epiphyseal growth plates and a compromised final adult height. In addition to the physical consequences of early puberty, social and psychological aspects may need to be considered.

14. In which sex is precocity more prevalent?

Precocious puberty predominantly affects girls. The disparity in overall prevalence of precocity is explained by the large numbers of girls with central idiopathic precocity, a condition that is less common in boys. At least 80% of all precocious puberty in girls is central idiopathic. The prevalence of organic causes of precocious puberty (CNS lesions, gonadal tumors, and specific underlying diseases) is similar in both sexes.

15. How is the diagnosis of precocious puberty made?

The diagnosis of precocious puberty requires the appearance of the physical signs of puberty before the defined age limits, as discussed previously. In both boys and girls, a complete history should be taken, with careful consideration of any exposure to exogenous steroids or estrogen receptor agonists (e.g., lavender oil or tea tree oil), onset of pubertal signs and rate of progression, presence or history of CNS abnormalities, and pubertal history of other family members. Height measurements should be plotted on a growth chart to determine growth pattern and growth velocity. A physical examination should be performed with a focus on Tanner staging, the presence of café-au-lait spots, and neurologic signs. One of the early steps in evaluating a child with early pubertal development should be to obtain a radiograph of the left hand and wrist to determine skeletal maturity (bone age). If the bone age is advanced, further evaluation is warranted. Sex steroid levels should be measured, especially in boys, because testosterone levels higher than the prepubertal range (> 10 ng/dL) confirm pubertal status. For girls, estradiol measurements are less reliable indicators of puberty, because most commercial assays are not sufficiently specific or sensitive to demonstrate an increase during early puberty.

16. How does GnRH-dependent (central) precocious puberty differ from GnRH-independent (peripheral) precocious puberty?

It is usually difficult to distinguish GnRH-dependent (central) from GnRH-independent (peripheral) precocity on physical examination. Central precocious puberty involves activation of the GnRH pulse generator, an increase in gonadotropin secretion, and a resultant increase in the production of sex steroids. Consequently, the sequence of hormonal and physical events in central precocious puberty is identical to the progression of normal puberty. Peripheral precocious puberty occurs independent of gonadotropin secretion. Although the possible causes of peripheral precocious puberty are more numerous (Box 43-1), central precocity accounts for most cases.

17. What is the single most important test in establishing a specific diagnosis?

The GnRH stimulation test is the single most important test to determine whether gonadotropin responses are consistent with central or peripheral precocious puberty. The diagnosis of central precocious puberty is made by demonstrating a pubertal LH response to GnRH. Measurement of random gonadotropins is typically not helpful because of overlap between prepubertal and early pubertal values until at least Tanner stage III. If random gonadotropins are measured, a third-generation assay is recommended because it has better discrimination between prepubertal and pubertal levels.

18. When is a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study of the brain indicated?

In girls younger than 6 years, and boys of any age, who are diagnosed with central precocious puberty, an MRI study of the brain should be performed to evaluate for CNS lesions. It is unlikely that an abnormality will be found in girls between 6 and 8 years old, so the need for an MRI in this age group should be assessed individually.

19. How is central idiopathic precocious puberty treated?

Children with central precocious puberty can be treated with GnRH agonists, such as leuprolide. GnRH agonists disrupt the endogenous pulsatile GnRH, thus downregulating pituitary GnRH receptors and decreasing gonadotropin secretion. The most important clinical criteria for GnRH agonist therapy is documented progression of pubertal development, which is based on the recognition that many girls with central precocious puberty, especially those between 6 and 8 years old, have a slowly progressive form and reach a normal adult height without intervention. With GnRH agonist treatment, physical changes of puberty regress or cease to progress, and linear growth slows to a prepubertal rate. Pubic hair and axillary hair typically do not regress. Projected final adult height often increases because of a slowing of skeletal maturation. GnRH agonists are generally given as a monthly depot intramuscular injection, and side effects are rare. There is also a small hydrogel implant that can be placed under the skin that releases a GnRH agonist (histrelin) continuously for about 1 year. Children receiving GnRH agonists should be monitored every 4 to 6 months to evaluate for pubertal regression or treatment failure. After discontinuation of therapy, pubertal progression resumes, and normal rates of fertility are expected.

20. What findings suggest peripheral precocious puberty?

In peripheral precocious puberty, basal serum FSH and LH levels are low, and the LH response to GnRH stimulation is suppressed by feedback inhibition of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis by the autonomously secreted gonadal steroids. Girls with ovarian cysts, ovarian tumors, or McCune-Albright syndrome generally have signs of estrogen excess such as breast development and possibly vaginal bleeding. In these girls, a pelvic ultrasound scan is diagnostic, and estradiol levels are markedly elevated. In boys with peripheral precocious puberty, laboratory studies should include serum testosterone, human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), DHEA-S, and androstenedione levels. Elevated adrenal androgens could indicate an adrenal tumor or CAH. To evaluate further for CAH, measurement of baseline or adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-stimulated steroid intermediates (e.g., 17-OHP, 17-hydroxypregnenolone, 11-deoxycortisol) is recommended. Asymmetric or unilateral enlargement of the testes suggests a Leydig cell tumor.

21. What is McCune-Albright syndrome?

McCune-Albright syndrome is a triad consisting of GnRH-independent precocious puberty, irregular (coast-of-Maine) café-au-lait lesions, and polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, but only two of these are necessary to make the diagnosis. It can affect both sexes, but it is seen infrequently in boys. In girls, breast development and vaginal bleeding occur with sporadic increases in estradiol from autonomously functioning ovarian cysts. Serum gonadotropin levels are low, and GnRH testing elicits a prepubertal response. With time, however, increased estradiol may mature the hypothalamus, thus leading to true central GnRH-dependent precocity. The syndrome can be associated with other endocrine dysfunction including hyperthyroidism, GH excess, and hypercortisolism. In affected tissues, there is an activating mutation in the gene that encodes the alpha-subunit of Gs, the G-protein that stimulates adenylate cyclase. Endocrine cells with this mutation have autonomous hyperfunction and secrete excess amounts of their respective hormones.

22. How is McCune-Albright syndrome treated?

Girls with McCune-Albright syndrome are generally treated with a medication that inhibits the aromatization of testosterone to estrogen, such as letrozole. Other trials have been performed using tamoxifen, an estrogen receptor antagonist. In boys, treatment consists of either inhibiting androgen production with ketoconazole or using a combination of an aromatase inhibitor that blocks the conversion of androgen to estrogen and an antiandrogen that antagonizes the effects of androgens at the receptor.

23. What is testotoxicosis, and how is it treated?

Familial testotoxicosis is a male-limited autosomal dominant, gonadotropin-independent form of male precocious puberty. Boys with this condition begin to develop true precocity with bilateral testicular and phallic enlargement and growth acceleration by 4 years of age. Serum testosterone levels are high, but serum gonadotropins are low, and GnRH testing shows a prepubertal response. By midadolescence to adulthood, GnRH stimulation demonstrates a more typical LH-predominant pubertal response. This condition is caused by an activating mutation in the gene encoding the LH receptor. The mutant LH receptors in the testes are constitutively overactive and do not require LH binding for their activity, but they produce testosterone autonomously. Treatment options are the same as for boys with McCune-Albright syndrome. If central precocious puberty has been induced, GnRH agonists may also be part of the treatment plan.

24. How does 21-hydroxylase-deficient CAH manifest?

The most common adrenogenital syndrome is 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Girls usually develop virilization in utero, resulting in a degree of sexual ambiguity. They are discovered at birth and should be diagnosed within the first few days of life by finding a greatly elevated serum 17-OHP level. Boys have normally formed genitalia and therefore are not identified on physical examination at birth. In the more common salt-losing form of the disease, boys present with vomiting, shock, and electrolyte disturbances at 7 to 10 days. Fortunately, with neonatal screening for 21-hydroxylase deficiency, boys are being diagnosed before they develop life-threatening electrolyte abnormalities. Small subsets of affected boys and girls do not waste salt and may present in early or late childhood with signs of adrenarche, such as pubic hair, acne, body odor, acceleration of linear growth, and skeletal maturation.

Treatment for all forms of CAH is directed at reducing serum androgen levels by replacing glucocorticoids to reduce pituitary secretion of ACTH. Insufficient glucocorticoid replacement leads to a compromise in final adult height secondary to advanced skeletal maturation, whereas excessive glucocorticoid replacement leads to short stature because of the direct effects of glucocorticoids on bone. Serum markers, growth curves, and bone age radiographs must be carefully monitored. In salt-wasting CAH, the mineralocorticoid fludrocortisone is also required. This is not necessary in the non–salt-wasting forms of CAH.

26. What is the association of hypothyroidism with precocity?

Rarely, severe primary hypothyroidism may cause breast development in girls and increased testicular size in boys. The exact mechanism is unclear, but one theory is that thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), which is elevated in primary hypothyroidism, can stimulate the FSH receptor on the gonads. These children generally present with growth deceleration as typically seen in hypothyroidism, rather than growth acceleration as typically seen in precocious puberty. Bone age is usually delayed. Thyroid hormone replacement results in regression of pubertal changes, and no other therapy is necessary.

27. What is adolescent gynecomastia? When and how should it be treated?

Normal boys often have either unilateral or bilateral breast enlargement during puberty. Breast development generally starts during early puberty and resolves within 2 years. The cause of gynecomastia is not clearly understood, but it may be related to an elevated ratio of estradiol to testosterone. Treatment consists primarily of reassurance and support. However, if resolution does not occur or if breast enlargement is excessive, surgery may be warranted. Surgery should be avoided until puberty is complete, to avoid recurrence of gynecomastia. Pathologic conditions associated with gynecomastia include Klinefelter syndrome and various other testosterone-deficient states. Tea tree oils and lavender oils have been associated with gynecomastia in boys. Some prescription medications, such as atypical antipsychotics, may cause gynecomastia and galactorrhea. Evidence is mixed regarding the connection of cannabis abuse and gynecomastia.

28. At what age does failure to enter puberty necessitate investigation?

Delayed puberty should be evaluated if there are no pubertal signs by 13 years in girls and by 14 years in boys. An abnormality in the pubertal axis may also manifest as a lack of normal pubertal progression, which is defined as more than 4 years between the first signs of puberty and menarche in girls or more than 5 years for completion of genital growth in boys.

29. How do body habitus and lifestyle influence the timing of puberty?

There is a high incidence of delayed puberty and primary amenorrhea in girls with anorexia nervosa and in girls who are highly competitive athletes. These girls have hypogonadotropic hypogonadism that appears to be directly related to their low body fat. Girls with a low body mass index (BMI) also have low circulating leptin and estrogen levels and are more likely to have delayed puberty or menstrual dysfunction. Leptin is a hormone produced by adipocytes that is important in hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal feedback signaling. Leptin deficiency has been associated with both anorexia and obesity, with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism present in both phenotypes. There appears to be a minimum leptin level that is permissive for pubertal development. When severely underweight girls improve their BMI, puberty ensues and progresses to menarche appropriately.

30. What is constitutional growth delay, and how does it affect puberty?

Constitutional growth delay is the most common cause of delayed puberty. Children with this growth pattern generally have a fall-off in their linear growth within the first 2 years of life. After this, growth returns to normal, but along a lower growth channel than would be expected for parental heights. Skeletal maturation is also delayed, and the onset of puberty is commensurate with bone age rather than chronologic age. For example, a 14-year-old boy with a bone age of 11 years will start puberty when his bone age is closer to 11.5 to 12 years. This delay in puberty postpones the pubertal growth spurt and closure of growth plates, so that the child continues to grow after his or her peers have reached their final adult height. A key feature of this growth pattern is normal linear growth after 2 years of age. There is often a family history of “late bloomers.”

31. When is hypogonadism diagnosed?

Functional or permanent hypogonadism should be considered when there are no signs of puberty and bone age has advanced to beyond the normal ages for puberty to start. A eunuchoid body habitus is often evident in children with abnormally delayed puberty; a decreased ratio of upper to lower body and a long arm span characterize this habitus. As a rule, serum gonadotropin levels are measured first to determine whether the child has hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (gonadotropin deficiency) or hypergonadotropic hypogonadism (primary gonadal failure). If a child’s bone age is less than the normal age for puberty to start, gonadotropin levels are not a reliable means of making an accurate diagnosis.

32. What are the causes of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism?

Normal or suppressed gonadotropins indicate a failure of the pituitary to stimulate gonadal steroid production. Chronic illness, malnutrition, excessive exercise, or anorexia can cause a functional deficiency of gonadotropins that reverses when the underlying condition improves. Hyperprolactinemia can also manifest as delayed puberty, and only 50% of the time will there be a history of galactorrhea. Other endocrinopathies such as diabetes mellitus, glucocorticoid excess, and hypothyroidism can cause hypogonadotropic hypogonadism when untreated. Permanent gonadotropin deficiency is suspected if these conditions are ruled out and gonadotropin levels are low. Gonadotropin deficiency may be associated with other pituitary deficiencies from conditions such as septo-optic dysplasia, tumors such as craniopharyngioma, trauma, empty sella syndrome, pituitary dysgenesis, Rathke pouch cysts, or cranial irradiation. Various syndromes, such as Kallmann syndrome, Laurence-Moon-Bardet-Biedl syndrome, and Prader-Willi syndrome are also associated with gonadotropin deficiency, so a karyotype or other genetic testing may be necessary. Drug abuse, particularly with heroin or methadone, has been associated with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Isolated gonadotropin deficiency (i.e., occurring without another pituitary deficiency) is often difficult to diagnose because hormonal tests do not absolutely distinguish whether a child can produce enough gonadotropins or whether he or she simply has very delayed puberty. If gonadotropin deficiency cannot be clearly distinguished from delayed puberty, a short course of sex steroids can be given. Patients with constitutional delay often enter puberty after such an intervention. If spontaneous puberty does not occur after this treatment or after a second course, the diagnosis of gonadotropin deficiency may be made.

33. What is Kallmann syndrome?

Kallmann syndrome is one of a class of disorders referred to as idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism or idiopathic hypothalamic hypogonadism. It occurs as frequently as 1 in 10,000 boys and 1 in 50,000 girls. The classic form is characterized by hypogonadotropic hypogonadism with hyposmia or anosmia. It is caused by aplasia or hypoplasia of the olfactory bulbs and is associated with hypoplasia or aplasia of other structures of the rhinencephalon (e.g., cleft lip or cleft palate, congenital deafness, and color blindness). Undescended testes and gynecomastia are common.

34. What are the causes of hypergonadotropic hypogonadism?

Elevated gonadotropin levels indicate a failure of the gonads to produce enough sex steroids to suppress the hypothalamic-pituitary axis. These levels are diagnostic for gonadal failure at two periods of time: before 2 to 3 years of age and after the bone age is at or beyond the normal age for puberty to start. If hypergonadotropic hypogonadism is diagnosed, a karyotype should be performed. Potential causes include the following:

Variants of ovarian or testicular dysgenesis: Turner syndrome, Klinefelter syndrome, Noonan syndrome, pure XX or XY gonadal dysgenesis

Variants of ovarian or testicular dysgenesis: Turner syndrome, Klinefelter syndrome, Noonan syndrome, pure XX or XY gonadal dysgenesis

Gonadal toxins: chemotherapy (particularly alkylating agents), radiation treatment

Gonadal toxins: chemotherapy (particularly alkylating agents), radiation treatment

Androgen enzymatic defects: 17-alpha-hydroxylase deficiency in the genetic male or female, 17-ketosteroid reductase deficiency in the genetic male

Androgen enzymatic defects: 17-alpha-hydroxylase deficiency in the genetic male or female, 17-ketosteroid reductase deficiency in the genetic male

Complete or partial androgen insensitivity syndrome

Complete or partial androgen insensitivity syndrome

Other miscellaneous disorders: infections, gonadal autoimmunity, vanishing testes, trauma, surgery, torsion

Other miscellaneous disorders: infections, gonadal autoimmunity, vanishing testes, trauma, surgery, torsion

35. What is Klinefelter syndrome?

Klinefelter syndrome is the most common cause of testicular failure and results from at least one extra X chromosome; the most common karyotype is 47,XXY. The incidence is 1 in 1000 male births, and eunuchoid body proportions are often present from early childhood. Associated features include gynecomastia, tall stature, small testes, low testosterone, and elevated serum gonadotropins. Learning disabilities and behavioral problems may also be present. Many boys with Klinefelter syndrome have spontaneous onset of pubic hair growth, but they fail to progress completely through puberty. Testosterone supplementation is indicated in many boys over time, and in some it is required to initiate puberty. Leydig cell function (testosterone production) is variable, but seminiferous tubular function is almost always abnormal. This generally results in infertility, and many of these men are not diagnosed until they are seen in an infertility clinic.

36. How is gonadal failure evaluated in girls?

In girls with gonadal failure (indicated by elevated gonadotropin levels) and no apparent cause, a karyotype evaluation should be performed because Turner syndrome is the most likely explanation. 46,XX gonadal dysgenesis can also occur and may be inherited as an autosomal recessive trait. A karyotype would also identify 46,XY gonadal dysgenesis in a phenotypic female who is actually a genetic male. In this condition, there is complete lack of testicular development, and consequently, except for the absence of gonads, normal female sexual differentiation occurs. If the karyotype is normal, then the evaluation should look for causes of premature ovarian failure, as discussed in question 34.

Any consideration of pubertal delay in girls must include the possibility of Turner syndrome. An absent or structurally abnormal second X chromosome characterizes Turner syndrome. The incidence of Turner syndrome is approximately 1 in 2000 live female births. However, the chromosomal abnormality is actually more common than this. Ninety percent or more of conceptuses with Turner syndrome do not survive beyond 28 weeks of gestation, and the 45,XO karyotype occurs in 1 out of 15 miscarriages. In the absence of a second functional X chromosome, oocyte degeneration is accelerated, leaving fibrotic streaks in place of normal ovaries. Because of primary gonadal failure, serum gonadotropin levels rise and are elevated at birth and again at the normal time of puberty.

38. What are the clinical findings in patients with Turner syndrome?

TABLE 43-2.

CLINICAL FINDINGS IN PATIENTS WITH TURNER SYNDROME

| PRIMARY DEFECTS | SECONDARY FEATURES | INCIDENCE (%) |

| Physical Features | ||

| Skeletal growth disturbances | Short stature | 100 |

| Short neck | 40 | |

| Abnormal upper-to-lower segment ratio | 97 | |

| Cubitus valgus | 47 | |

| Short metacarpals | 37 | |

| Madelung deformity | 7.5 | |

| Scoliosis | 12.5 | |

| Genu valgum | 35 | |

| Characteristic facies with micrognathia | 60 | |

| High arched palate | 36 | |

| Lymphatic obstruction | Webbed neck | 25 |

| Low posterior hairline | 42 | |

| Rotated ears | Common | |

| Edema of hands and feet | 22 | |

| Severe nail dysplasia | 13 | |

| Characteristic dermatoglyphics | 35 | |

| Unknown factors | Strabismus | 17.5 |

| Ptosis | 11 | |

| Multiple pigmented nevi | 26 | |

| Physiologic Features | ||

| Skeletal growth disturbances | Growth failure | 100 |

| Otitis media | 73 | |

| Germ cell chromosomal defects | Gonadal failure | 96 |

| Infertility | 99.9 | |

| Gonadoblastoma | 4 | |

| Unknown factors: embryogenic | Cardiovascular anomalies | 55 |

| Hypertension | 7 | |

| Renal and renovascular anomalies | 39 | |

| Unknown factors: metabolic | Hashimoto thyroiditis | 34 |

| Hypothyroidism | 10 | |

| Alopecia | 2 | |

| Vitiligo | 2 | |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 2.5 | |

| Carbohydrate intolerance | 40 |

Data from Hall J, Gilchrist D: Turner syndrome and its variants. Pediatr Clin North Am 37:1421, 1990.

39. What features are present in the history of an adolescent with pubertal delay?

The history should include questions regarding the presence of chronic illnesses, autoimmune disorders, nutritional disorders, exercise history, galactorrhea, sense of smell, family history of infertility, and timing of puberty in parents and siblings. Weight gain or loss should also be noted.

40. What features are present in the physical examination of an adolescent with pubertal delay?

Physical examination should include measurement of arm span and upper-to-lower-segment ratio. Eunuchoid body proportions occur early in patients with Klinefelter syndrome and late in those with other forms of hypogonadism. Signs of any chronic illness, malnutrition, anorexia, hypothyroidism, glucocorticoid excess, or features of Turner syndrome (girls) or Klinefelter syndrome (boys) should be noted. A careful examination should be made for any signs of puberty, such as pubic hair, axillary hair, acne, testicular size (boys), penile length (boys), or breast development (girls). Pubic hair may represent only adrenal androgen production. Testicular volume greater than 4 mL (length > 2.5 cm) indicates gonadotropin stimulation. Breast development and vaginal maturity are indicators of estrogen exposure. In addition, visual fields and olfaction should be evaluated (80% of boys with Kallmann syndrome have a reduced, or absent, sense of smell). The growth chart should be analyzed to evaluate for short stature and to determine whether linear growth has been normal.

41. How are radiographic studies and gonadotropin levels helpful in the diagnosis of pubertal delay?

Assessment of bone age is critical in determining biologic age and the time of expected pubertal development. If linear growth is normal and the bone age is less than the normal age for pubertal onset, the diagnosis is likely to be constitutional growth delay. If linear growth is impaired and the bone age is delayed, it may be necessary to evaluate GH or thyroid function. If the bone age has advanced beyond the age for normal puberty, gonadotropin levels are helpful to distinguish between gonadotropin deficiency and primary gonadal failure.

42. What other laboratory tests may be needed?

Additional laboratory studies may include a chemistry panel, complete blood cell count, celiac testing, thyroid function tests, estradiol (girls), testosterone (boys), and prolactin levels. If gonadotropins are elevated, chromosome analysis is indicated for both genders to evaluate for Turner syndrome (girls) or Klinefelter syndrome (boys). In the case of low gonadotropin levels, olfactory testing and cranial MRI are recommended.

43. How is delayed puberty managed?

The treatment of delayed puberty depends on the underlying cause. If the delayed pubertal development is secondary to anorexia, hypothyroidism, or illness, treatment of these underlying conditions results in spontaneous onset of puberty. Puberty also begins spontaneously, albeit late, in constitutional growth delay, so reassurance alone to the patient and family may be sufficient. In some patients with constitutional growth delay, treatment to induce puberty may be appropriate. For boys, a 4- to 6-month course of low-dose depot testosterone (50–100 mg intramuscularly every 4 weeks) can be offered if the bone age is at least 11 to 12 years. This treatment results in some early virilization, without adversely affecting final adult height. Spontaneous puberty usually begins, as evident by testicular enlargement, 3 to 6 months after the end of the testosterone course. For girls, a 3-month course of low-dose estradiol (0.25–0.5 mg orally every day) can be offered if the bone age is at least 10 to 11 years. Therapy is then stopped, and physical changes are evaluated. Withdrawal bleeding is unusual after one course of estrogen therapy, but it may occur with subsequent courses.

44. What is the treatment of hypogonadism in boys?

In boys with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism for whom fertility is not an immediate issue, and in all boys with primary hypogonadism, long-term testosterone therapy is required. While the patient is growing, careful attention must be paid to growth velocity and bone age. Most commonly, depot testosterone esters (enanthate or cypionate) are used in 25- to 50-mg doses intramuscularly every 3 to 4 weeks for the first 1 to 2 years of therapy. By the second or third year of therapy, the dose is raised to 50 to 100 mg every 3 to 4 weeks. The adult maintenance dose is 200 to 300 mg every 3 to 4 weeks. Alternatively, a transdermic testosterone patch or gel may be used.

45. How is estrogen treatment given for girls with hypogonadism?

Estrogen replacement therapy in hypogonadal girls is begun with very low-dose unopposed estrogen treatment for 12 to 18 months. The dosage used varies depending on height projections and individual response. Following this period of unopposed estrogen, progesterone is added for 10 to 12 days of each month, and eventually a birth control pill may be prescribed. Progesterone therapy is necessary to counteract the effects of estrogen on the uterus; unopposed estrogen can cause endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma. Replacement of gonadal steroids in both sexes is also necessary for normal bone mineralization and to prevent osteoporosis.

46. How is Turner syndrome treated?

Approximately 10% to 20% of girls with Turner syndrome have some ovarian function at puberty that allows for early breast development. A small percentage of this group will have normal periods, and an even smaller percentage (< 1% of all girls with Turner syndrome) will actually be fertile. Most girls with Turner syndrome require exogenous gonadal steroid replacement. Low-dose unopposed estradiol, followed by cycling with estrogen and progestin, allows for development of secondary sexual characteristics. The timing for initiation of estrogen is critical and should be decided by an endocrinologist through discussions with each patient and her family. This decision depends on several factors, including height and psychosocial factors. The short stature of girls with Turner syndrome is treated with GH. Final adult height in girls with Turner syndrome is related to when GH is initiated, with better outcomes in girls who are started at a younger age. Consequently, early diagnosis of Turner syndrome is essential.

A girl who has not had menarche by 16 years of age, or within 4 years after the onset of puberty, is considered to have primary amenorrhea. Secondary amenorrhea is diagnosed if more than 6 months have elapsed since the last menstrual period, or if more than the length of three previous cycles has elapsed with no menstrual bleeding.

48. How do you evaluate a girl with amenorrhea?

To sort out the many causes of amenorrhea, it is helpful to distinguish girls who produce sufficient estrogen from those who do not by performing a progesterone challenge. Girls who are producing estrogen will have withdrawal bleeding after 5 to 10 days of oral progesterone, whereas those who are estrogen-deficient will have very little or no bleeding. Those who do not have bleeding should be evaluated for hypogonadism as described previously. However, in two situations, girls who have sufficient estrogen will not have withdrawal bleeding: obstruction of the cervix and absence of the cervix or uterus. In Rokitansky syndrome, maldevelopment of the müllerian structures leads to an absent or hypoplastic uterus or cervix (or both). Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (testicular feminization) in a genetic male results in a phenotypic female who has normal breast development because of the aromatization of testosterone to estrogen. The production of antimüllerian hormone in patients with androgen insensitivity syndrome leads to regression of the müllerian structures and thus the absence of a uterus. The absence of a cervix is a diagnostic finding in both Rokitansky syndrome and complete androgen insensitivity syndrome. Consequently, a pelvic examination should be considered in all girls who present with amenorrhea, especially primary amenorrhea.

49. What causes amenorrhea in girls who are producing estrogen and do not have an outflow tract obstruction?

Amenorrhea in girls who are producing normal or even elevated amounts of estrogen is a manifestation of anovulatory cycles. Irregular menses may also be a sign of chronic anovulation given that estrogen production, unopposed by progesterone, leads to endometrial hyperplasia and intermittent shedding. Because menarche is normally followed by a period of anovulatory cycles and irregular menses, many adolescents with a pathologic cause of amenorrhea may be missed. Consequently, it is important to evaluate all girls who do not have regular menses by 3 years after menarche. The most common cause of chronic anovulation is polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), a disorder characterized by increased ovarian androgen production. The clinical presentation of PCOS varies and may include amenorrhea, oligomenorrhea, dysfunctional uterine bleeding, hirsutism, acne, or obesity. PCOS is further discussed in a separate chapter.

Bondy, CA, Care of girls and women with Turner syndrome. a guideline of the Turner Syndrome Study Group. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:10–25.

Carel, JC, et al. Consensus statement on the use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs in children. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e752–e762.

Durbin, KL, Van Wyk and Grumbach syndrome. an unusual case and review of the literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2011;24:1083–3188.

Eugster, EA, Peripheral precocious puberty. causes and current management. Horm Res. 2009;71(Suppl 1):64–67.

Eugster, EA, Clarke, W, Kletter, GB, et al, Efficacy and safety of histrelin subdermal implant in children with central precocious puberty. a multicenter trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:1697–1704.

Gordon, CM. Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:365–371.

Grumbach MM, Styne DM: Puberty: ontogeny, neuroendocrinology, physiology, and disorders. In JD Wilson, Foster DW, Kronenberg HM, Larsen PR, editors: Williams textbook of endocrinology, ed 9, Saunders: Philadelphia, pp 1509–1625.

Grumbach, MM. The neuroendocrinology of human puberty revisited. Horm Res. 2002;57(suppl 2):2–14.

Herman-Giddens, ME, Slora, EJ, Wasserman, RC, et al, Secondary sexual characteristics and menses in young girls seen in office practice. a study from the Pediatric Research in Office Setting network. Pediatrics 1997;99:505–512.

Ibanez, L, Virdis, R, Potau, N, et al. Natural history of premature pubarche and auxological study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;74:254.

Kaplan, S, Grumbach, M. Pathophysiology and treatment of sexual precocity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;71:785.

Kaplowitz. PB Link between body fat and the timing of puberty. Pediatrics. 2008;121(Suppl 3):208–217.

Kulin, H, Rester, E. Managing the patient with a delay in pubertal development. Endocrinologist. 1992;2:231.

Layman, LC. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2007;36:283–296.

Levine, M, The McCune-Albright syndrome. the whys and wherefores of abnormal signal transduction. N Engl J Med 1991;325:1738–1740.

Magiakou, MA, Manousaki, D, Papadaki, M, et al, The efficacy and safety of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog treatment in childhood and adolescence. a single center, long-term follow-up study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:109–117.

Matejek, N, Weimann, E, Witzel, C, et al. Hypoleptinaemia in patients with anorexia nervosa and in elite gymnasts with anorexia athletica. Int J Sports Med. 1999;20:451–456.

Nathan, BM, Palmert, MR. Regulation and disorders of pubertal timing. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2005;34:617–641.

Nelson, LM, Clinical practice. primary ovarian insufficiency. N Engl J Med 2009;360:606–614.

Oakley, AE, Clifton, DK, Steiner, RA. Kisspeptin signaling in the brain. Endocr Rev. 2009;30:713–743.

Pasquino, AM, Pucarelli, I, Accardo, F, et al, Long-term observation of 87 girls with idiopathic central precocious puberty treated with gonadotropin releasing hormone analogs. impact on adult height, body mass index, bone mineral content, and reproductive function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:190–195.

Root, AW. Precocious puberty. Pediatr Rev. 2000;21:10–19.

Rosenfield, R. Diagnosis and management of delayed puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;70:559–562.

Wu, T, Mendola, P, Buck, GM, Ethnic differences in the presence of secondary sex characteristics and menarche among US girls. the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Pediatrics 2002;110:752–757.

Wheeler, M, Styne, DM. Diagnosis and management of precocious puberty. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1990;37:1255–1271.

Williams, RM, Ward, CE, Hughes, IA. Premature adrenarche. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97:250–254.