Disorders of large bowel motility, structure and perfusion

Introduction

Sigmoid volvulus is an acute condition resulting from chronic dilatation of the sigmoid colon plus an acute twisting of the sigmoid loop on a narrow mesentery, resulting in obstruction and massive dilatation (see below, Fig. 29.1, p. 378–379).

Modern diet and disease

Mechanisms of disease caused by modern diet

Whilst the increase in calories and nutrients has brought benefits, it has also brought problems. The modern diet adversely affects both bowel function and metabolism, particularly of lipids. Box 29.1 outlines the important ways in which modern diet can induce disease and dysfunction. With regard to bowel diseases, the most important diet-related factors are likely to be faecal volume and consistency, together with gastrointestinal transit time. The average Western adult passes between 80 and 120 g of firm stool each day with a transit time of about 3 days, although transit time can be as long as 2 weeks in the elderly. In contrast, rural dwellers in the developing world, with a diet similar to the hunter-gatherer, pass between 300 and 800 g of much softer stool each day, with an average transit time of less than a day and a half.

Dietary fibre content

An essential part of managing many bowel conditions (other than irritable bowel syndrome) and preventing others is a substantial increase in dietary fibre intake. Box 29.2 lists foods with a high fibre content that can be eaten regularly with little effort or extra expense. Increasing the fibre content almost inevitably leads to reduced consumption of refined carbohydrates and saturated animal fats and lower total energy intake. Patients should introduce dietary fibre gradually because a sudden increase is likely to cause abdominal discomfort and distension and more flatus. Bulking agents (ispaghula husk preparations) can be taken in the early stages for a rapid result whilst avoiding unpleasant side-effects.

Irritable bowel syndrome

Constipation

Management of constipation

Diagnosis of constipation in children is usually made on the history and examination; successful treatment confirms the diagnosis. If chronic severe constipation persists in infants despite treatment, a diagnosis of ultra-short segment Hirschsprung’s disease (see Ch. 50) should be considered. In the elderly, a dietary and drug history should be obtained, and blood tests performed to exclude metabolic causes of constipation. It is vital to differentiate constipation from early large bowel obstruction in this group of patients. Carcinoma or the complications of diverticular disease should be excluded by sigmoidoscopy and barium enema, colonoscopy or CT pneumocolon.

In severe constipation, treatment involves a series of measures used progressively:

• Discontinue constipating medication

• Rectal measures: lubricant glycerine suppositories, small phosphate enemas, stool-softening arachis oil enemas, manual disimpaction (may require general anaesthesia)

• Oral agents (Box 29.3): senna, bisacodyl or osmotic laxatives containing macrogol (polyethylene glycol 3350). A more radical method is to use oral sodium picosulfate (as used in surgical bowel preparation), along with adequate oral or intravenous fluids to avoid dehydration. Note that if powerful oral laxatives are given to an obstructed patient, life-threatening perforation of the bowel can occur

• Oral ‘maintenance’ medications: sodium docusate as a stool softener, lactulose, Fybogel

In milder long-term constipation, dietary measures should be used. Many patients take a high-fibre diet but do not drink enough, failing to recognise that both are necessary to produce the benefits of fibre. Many women fail to gain from a high-fibre diet; clearly, increasing their fibre even more does not improve matters. If the condition is not severe, then eating more figs, apricots and prunes may solve the problem. Otherwise, a low dose of a stimulant laxative taken intermittently may be needed.

Sigmoid volvulus (Fig. 29.1)

Pathophysiology of sigmoid volvulus

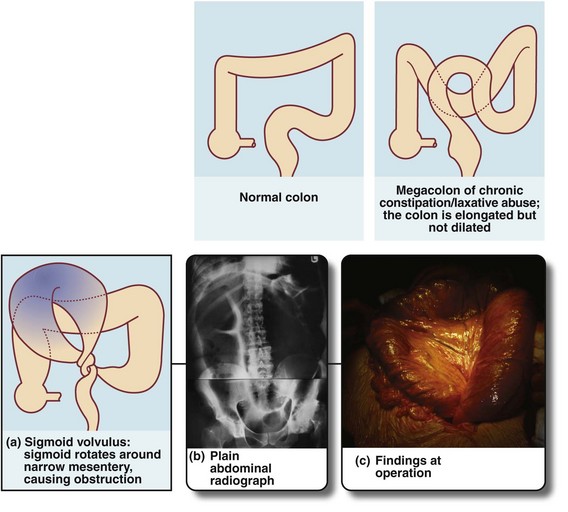

Fig. 29.1 Normal colon, megacolon and sigmoid volvulus

(a) Schematic diagram showing a grossly distended fluid-filled sigmoid colon twisted about its narrow neck, producing a ‘closed-loop’ obstruction; the loop is beginning to undergo necrosis. (b) and (c) This 35-year-old man with Down’s syndrome presented with a massively swollen abdomen and total constipation. (b) Plain abdominal radiograph showing the abdomen filled with the dilated sigmoid loop, confirming the clinical diagnosis of sigmoid volvulus. Note the abdomen was so distended that two films were required to cover the area. The volvulus could not be relieved by gentle passage of a flatus tube. At operation (c), the hugely distended sigmoid emerged from the laparotomy wound. The loop had twisted three times around its narrow base and the colon was of doubtful viability. This sigmoid colon was resected without untwisting the volvulus

Occasionally, a huge sigmoid loop, heavy with faeces and distended with gas, becomes twisted on its mesenteric pedicle (often abnormally narrow) to produce a closed-loop obstruction (see Fig. 29.1a–c). If this volvulus is not corrected, venous infarction ensues, followed by perforation and catastrophic faecal peritonitis. This full picture is uncommon, but there is often a history of transient episodes of abdominal pain diagnosed as constipation. Note that volvulus elsewhere, of the caecum, small bowel or stomach is unrelated to constipation.

Management of sigmoid volvulus

Plain abdominal X-ray usually shows a single grossly dilated sigmoid loop, often reaching the xiphisternum (see Fig. 29.1). An erect film may reveal a characteristic ‘inverted U’ or ‘coffee-bean sign’ of bowel gas in the upper abdomen, with fluid levels at the same height in the two bowel limbs in the lower abdomen; a lateral decubitus X-ray may reveal two parallel fluid levels running the length of the abdomen.

Diverticular disease

Clinical presentations of diverticular disease and their management

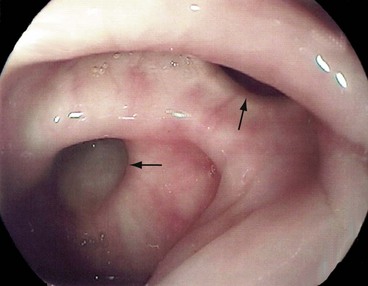

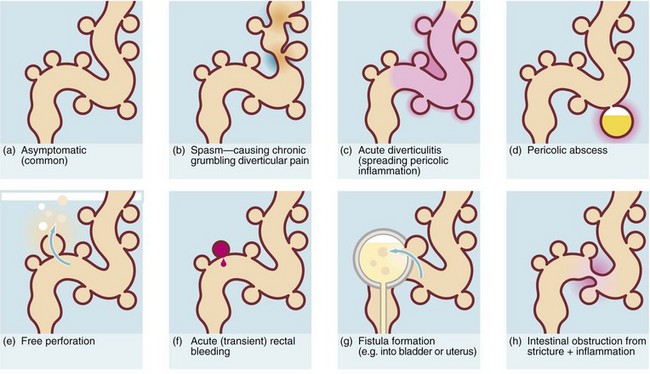

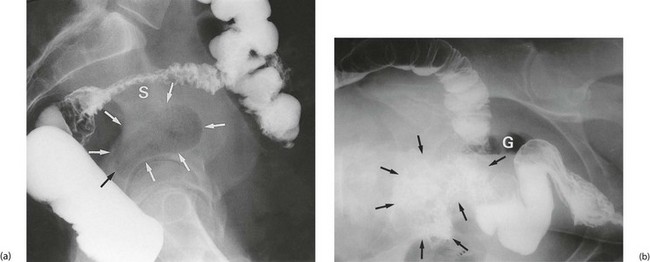

The consequences of diverticular inflammation are collectively described as diverticulitis and are summarised in Figure 29.3. Most people with diverticula are asymptomatic, and diverticula are a common incidental finding when the colon is investigated by barium enema or colonoscopy. Typical appearances are shown in Figures 29.2 and Fig. 29.4.

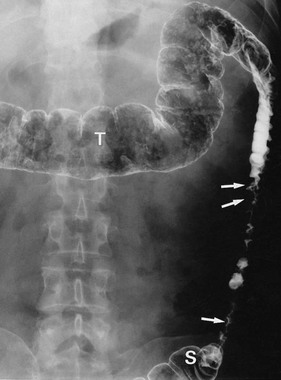

Fig. 29.2 Diverticular disease

Barium enema showing the typical appearance of multiple diverticula (arrowed) in the sigmoid and descending colon in a 77-year-old woman. A few diverticula are also present in the transverse colon

Pericolic abscess (see Fig. 29.3d)

Pericolic abscess represents a further extension of the pathological process just described. The clinical presentation is similar at first but fails to resolve with antibiotics. The patient suffers persistent pain and tenderness, a swinging pyrexia and incomplete obstruction due to spasm of bowel wall muscle. Sometimes a pericolic abscess presents as ‘pyrexia of unknown origin’ or even systemic sepsis (septicaemia). A pericolic abscess may drain spontaneously into bowel, producing an attack of purulent diarrhoea; the condition then resolves. Diagnosis of a pericolic abscess is made on CT scan. A contrast enema may show leakage of contrast into the abscess cavity (see Fig. 29.5).

Antibiotic therapy is the first line of treatment for abscesses < 4 cm. Ideally, this allows the abscess to be contained, and then resolve or drain spontaneously into bowel. Abscesses > 4 cm can be drained percutaneously under radiological guidance. If this treatment fails, operation is required. This is a major procedure usually involving exploration and drainage of the abscess and diverting the faecal stream via a colostomy. The affected segment of bowel must be removed to prevent recurrence. Note that perforated carcinoma can present in a similar way and histological diagnosis is mandatory. The surgical options are to leave a rectal stump for later reanastomosis (Hartmann’s operation, see Fig. 27.8, p. 359), a safe operation for non-specialists, or to primarily reanastomose the bowel ends. Reanastomosis is not attempted in faecal peritonitis or in a frail patient, as the chances of success are remote.

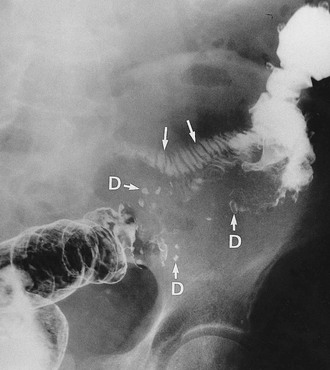

Fistula formation into other abdominal or pelvic structures (Fig. 29.3g)

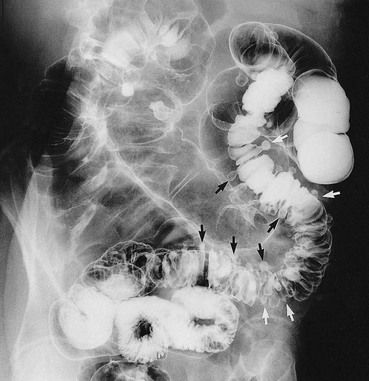

Fistula formation can occur when an inflamed diverticulum lies close to another hollow viscus. Inflammatory adhesions develop and the diverticulum then ruptures into the other viscus. A fistula between large bowel and small bowel (see Fig. 29.6) causes diarrhoea. A vesico-colic fistula causes pneumaturia and severe urinary tract infection. A fistula into the vagina after a previous hysterectomy causes a purulent vaginal discharge. Diverticular disease is the most common cause of these types of fistula but they may also be caused by Crohn’s disease and sometimes colorectal cancers.

Intestinal obstruction (Fig. 29.3h)

Diverticular disease occasionally presents with large bowel obstruction due to acute inflammatory thickening, muscle hypertrophy and spasm. Incomplete obstruction is more common and presents as severe constipation. Chronic diverticular inflammation sometimes causes local fibrous strictures, particularly in the sigmoid, which cause intermittent bouts of constipation when the stool is dry. When detected radiologically or endoscopically, these strictures must be distinguished from malignancy or Crohn’s disease by biopsy (Figs. 29.5 and 29.7).

Colonic angiodysplasias

Colonic angiodysplasias have been recognised as a common cause of acute or chronic rectal bleeding and iron deficiency anaemia since the mid-1970s. The lesions are tiny hamartomatous vascular lesions in the colonic wall, usually in the ascending colon, and produce bleeding out of proportion to their size (see Fig. 29.8). They may also occur in the stomach and small bowel. The origin of colonic angiodysplasias is unknown but since they occur later in life, they are probably acquired and degenerative.

Ischaemic colitis

Ischaemic colitis is a condition of the elderly which usually presents with rectal bleeding. The history is characteristic; there is a bout of cramp-like abdominal pain lasting a few hours, followed by an attack of rectal bleeding. Usually the bleeding is dark red, often without faeces, and occurs one to three times over about 12 hours. The episode then ceases spontaneously. The differential diagnosis includes acute bleeding from diverticular disease. The cause is transient ischaemia of a segment of large bowel, followed by sloughing of the mucosa with the splenic flexure the most vulnerable. Further attacks occasionally occur but most patients have no further trouble. Investigation by barium enema in the acute stage may reveal colonic oedema in the affected segment (see Fig. 29.9). A rare late complication is fibrotic stricturing of the area affected by ischaemia.