CHAPTER 3 DISORDERS OF LANGUAGE

There are two main schools of thought in the history of neurogenic language disorders, both of which have relevance to modern aphasiology. The first, the Wernicke-Lichtheim-Geschwind tradition, emphasized that primary language functions are represented in discrete regions of cortex (“centers”) and that the activities of these loci are integrated through connecting fiber tracts. The Wernicke-Lichtheim scheme consisted of a center for motor images of words, located in the posterior third of the inferior frontal convolution (Broca’s area), as well as a center for acoustic images of words (Wernicke’s area). A fiber tract (arcuate fasciculus) joined the two centers, with the flow of information running from posterior to anterior. A third center for concepts was located in the extrasylvian cortex, with an outflow to Broca’s area and input from Wernicke’s area. There was an output from Broca’s area to the motor cortex and an input to Wernicke’s area from the auditory cortex. This simple scheme systematized the main perisylvian and transcortical aphasia syndromes observed before 1885 and predicted the existence of a syndrome as yet unobserved at that time: conduction aphasia. The Wernicke-Lichtheim model was later refined by members of the Boston School, principally Frank Benson and Norman Geschwind, with the addition of three new syndromes, and the inclusion of the inferior parietal lobule as language cortex (see Benson and Ardila, 1996).

The second main stream is represented by neurologists such as Hughlings Jackson, Sigmund Freud, and Aleksandr Luria who conceived of language as represented in broader hierarchical cortical zones or gradients, organized around the centers of the Wernicke-Lichtheim model. The role of connecting tracts was deemphasized. Luria’s aphasiology preserves the anteroposterior schema of the Wernicke-Lichtheim model but redefines localization of language as hierarchical and distributed. Modern clinical aphasiology is based on the classical syndromes described in the Wernicke-Lichtheim tradition and their modifications. Concepts of their localization, however, have come to be shaped further by ongoing clinicopathological observation and functional neuroimaging, and current views on the localization of language are not too distant from those of the Jackson-Freud-Luria tradition. Linguistic ideas have also become part and parcel of modern aphasiology. A glossary of important linguistic terms and concepts is given in Table 3-1.

TABLE 3-1 Essential Linguistics Concepts

| Phonological | Phonology is the study of the structure and patterning of the sounds of language. Many of the clinical features of language disorders are phonological. The units of analysis are phonemes, which can be defined as the basic meaning-distinguishing sounds (essentially consonant and vowel sounds) of the language. |

| Lexical | Whereas phonology is concerned with the patterning of sounds within a word, and is therefore a sublexical discipline, lexicology is concerned with the whole word as a single entity. At a lexical level, there is a dichotomy that is fundamental to the understanding of aphasic disorders, because aphasic variants affect the two classes of words differentially. The open class, so-called because it is conceptually unlimited and new items are steadily added as vocabularies increase, consists principally of nouns, verbs, adverbs, and adjectives—that is, words that refer to specific objects, actions, and attributes and that convey substantive content. The closed class, which is conceptually limited and does not increase in size as vocabularies increase, consists of articles (e.g., “a,” “the,” “that”), conjunctions (e.g., “and,” “but”), pronouns (e.g., “you,” “they”), and prepositions (e.g., “up,” “along,” “below”). The distinction between open- and closed-class words parallels the distinction between the meaning of a sentence (semantics) and the form or sequential structure of a sentence (syntax). |

| Morphological | Morphology concerns the internal structure of words. The aspect of morphology that is most important for understanding language disturbances is word formation, or the construction of a new word from an existing word by adding an affix. This can be derivational, whereby an adjective such as “good” is converted to a noun such as “goodness,” or inflectional, whereby a word is changed to suit the grammar of a sentence; for example, “run” might become “running,” or “pencil” might become “pencils.” Because the suffixes “-ing” and “-s” cannot stand alone, they are referred to as bound morphemes. |

LANGUAGE PRODUCTION

At a clinical level, language disorders are more easily recognized and identified in language production, either spoken or written, than in disturbances of comprehension. Production consists of three broad stages: conceptualization, formulation, and overt execution. The first two of these stages are described in detail in the following sections. From a neuroanatomical perspective, conceptualization (the development of an intention to speak, and a decision about what will be said) depends on the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Formulation (the conversion of ideas into the structure of spoken language) depends on Broca’s region. Execution is the production of physical speech and depends on all of the motor mechanisms associated with speech (see Duffy, 2005).

Conceptualization

This is a largely prelinguistic phase that involves the development of an intention to speak and a decision as to what will be said. Development of an intention and a decision about the message to be conveyed is often referred to as macroplanning. From that point on, the message must be reshaped into a particular set of logical relationships (propositions) that can be expressed in terms of the syntactic and semantic structure of language. This is often referred to as microplanning. Propositions form a link between thought and its expression in language. It is noteworthy that this concept was anticipated by the British neurologist Hughlings Jackson, who regarded it as essential for understanding the relationship between thought and speech in aphasia. Conceptualization depends on connectivity between extrasylvian association cortex and the classical perisylvian language axis, a concept borne out by functional neuroimaging (see Blank, Scott, Murphy, et al, 2002).

Formulation

This phase deals with the conversion of propositions into actual sentences (sentence encoding). It is governed directly by the rules of syntax and semantics and consists of two important components. The first involves the selection of appropriate open class of lexical items (see Table 3-1) to convey the intended meaning. The linguistic concept of selection is of central importance in aphasic disorders. Selection implies the possibility of choice among alternatives, and errors in selection manifest clinically as paraphasias. A paraphasia has two essential features: (1) It is an error of selection resulting in the substitution of a word or part of a word with a frequently incorrect or inappropriate alternative, and (2) it is unintended. Selection processes occur at the phonemic and the semantic levels (see Table 3-1). In neuroanatomical terms, selection processes are heavily, but not exclusively, dependent on posterior perisylvian association cortices. The second component of formulation involves the genesis of correctly ordered positional slots into which the words of the sentence are inserted. These sequentially ordered schemas are often called sentence frames, and their construction is contributed to and defined by closed class (function) words and bound morphemes (see Table 3-1) Sentence frames are constructed according to the rules of syntax (see Table 3-1). The functional neuroanatomy of syntactic processing is complex, involving a network of left perisylvian structures, and it appears that Broca’s area is a key nodal structure within this network. Disorders of syntax, including Broca’s aphasia, occur most prominently with lesions involving the anterior aspects of the perisylvian language zone.

Fluency

The division of language disturbances into fluent and nonfluent is the most fundamental and clinically appreciable dichotomy in diagnostic aphasiology. The major aphasia syndromes are encompassed within the distinction of fluent versus nonfluent (see Table 3-2).

| Nonfluent Production | Fluent Production | |

|---|---|---|

| Anatomical | Anterior (prerolandic) language areas | Posterior (postrolandic) language areas |

| Fundamental disorder | Sequential organization (conceptualization, formulation) | Selection |

| Syndrome | Perisylvian | Perisylvian |

| Aphemia | Pure word deafness | |

| Broca’s aphasia | Wernicke’s aphasia | |

| Extrasylvian | Conduction aphasia | |

| Transcortical motor aphasia | Extrasylvian | |

| Transcortical sensory aphasia | ||

| Anomic aphasia |

Note: Mixed transcortical aphasia and global aphasia are associated with clinically nonfluent production but also involve an underlying selection disorder.

Fluent language output in an aphasic patient is defined by the use of sentences that are syntactically intact but are semantically compromised because of a selection disorder. The following example, taken from a description of a severe form of fluent dysphasia, namely jargonaphasia (a variant of Wernicke’s aphasia), illustrates this point:1

Paraphasia and Other Deviations

Paraphasias

Paraphasias are defined as unintended utterances. In essence, there is a failure of selection at the phonemic level, producing a phonemic (literal) paraphasia (e.g., “I drove home in my lar”) or at a word (lexical) level (e.g., “I drove home in my wagon”), producing a verbal paraphasia (Table 3-3). Paraphasias are said to be neologistic when the unintended word is heavily contaminated with extraneous phonemes and, as a result, contains juxtapositions of sublexical fragments that are not characteristic of the language (phonemic neologisms) and are nonsensical in context. For example:5

| Type | Examples |

|---|---|

| Phonemic (literal) | “glear” instead of “clear” |

| “spink” instead of “sphinx” | |

| “gedrees” instead of “degrees” | |

| “tums” instead of “tongs” | |

| Conduit d’approche (successive phonemic approximations to a target word) | “trep”→“tretz”→“fretful”→“pretzel” |

| Verbal | |

| Formal (similar form, different meaning) | “dare” instead of “pear” |

| Morphemic (assembled from legal morphemes) | “man-a-time,”* “summer-ly” |

| Semantic (substituted word belongs to the same general category) | “train” instead of “car” |

| “Taj Mahal” instead of “pyramid” | |

| “cloth” instead of “blanket” | |

| “seahorse” instead of “unicorn” | |

| Circumlocutions (word substituted with a phrase of the same meaning) | “drinking container” instead of “cup” |

* Morphemic assemblies that do not produce acceptable words are called neologisms.

EXAMINER: Are you feeling better than this morning?

PATIENT: Not too melsise, I don’t think.

Unintended substitutions also occur in writing (paragraphias). Like paraphasias, they can be literal or they can involve semantic substitutions (see Table 3-3).

APHASIA SYNDROMES

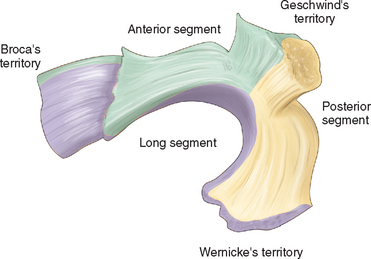

Contrary to earlier views, more recent tractography findings indicate that the arcuate fasciculus consists of two components. The first is a direct tract connecting the posterior segments of the inferior and middle temporal gyri with Broca’s area (Brodmann’s areas 44 and 45), as well as with parts of the middle frontal gyrus and inferior precentral gyrus. The second component is an indirect tract with anterior and posterior segments. The posterior segment connects Wernicke’s area with the inferior parietal lobule (Brodmann’s areas 39 and 40), whereas the anterior segment connects the inferior parietal lobule with frontal language cortex (see Catani et al, 2005). Structures connected by the arcuate fasciculus are somewhat more extensive than classical views suggested, and this broader concept of the perisylvian region accommodates the clinicopathological studies of fundamental language disorders since the 1950s more successfully. Furthermore, it suggests that the arcuate fasciculus might be important in uniting perisylvian and extrasylvian language regions.

Aphasias caused by anterior (prerolandic) lesions are associated with nonfluent language production, whereas those caused by posterior lesions (postrolandic) are associated with fluent disorders. There are two major nonfluent aphasias: Broca’s aphasia, in which repetition is disturbed, and transcortical motor aphasia (TMA), in which repetition is normal. The fluent aphasias are Wernicke’s and conduction aphasias, in which repetition is disturbed, and anomic and transcortical sensory aphasias (TSA), in which repetition is preserved (Table 3-4) (see LaPointe, 2005). In addition, there are two aphasias in which the dysfluency typical of anterior dysphasias is combined with the impaired comprehension typical of posterior dysphasias: global aphasia and mixed transcortical aphasia.

TABLE 3-4 Classification of Aphasia by Fluency and Comprehension

| Impaired Repetition | Normal Repetition |

|---|---|

| Nonfluent | |

| Broca’s* | Transcortical motor |

| Global† | Mixed transcortical |

| Fluent | |

| Conduction* | Anomic |

| Wernicke’s† | Transcortical sensory |

Nonfluent Production with Impaired Repetition: Speech Dyspraxia and Broca’s Aphasia

Speech Dyspraxia (Aphemia)

The syndrome of speech dyspraxia occurs quite separately from the other anterior aphasias. There is, however, a widely recognized dictum in aphasiology that lesions restricted to Broca’s area do not necessarily cause Broca’s aphasia. Embolic infarctions of Brodmann’s areas 44 and 45, often involving subjacent white matter and extension into the anterior insula, cause a wide spectrum of acute effects ranging from subtle hesitancy to mutism. Recovery is rapid—within days, weeks, or months—and in some cases, minimal residual dysfluency may be the only detectable language feature. Dyspraxia of facial, oropharyngeal, lingual, and respiratory functions is an associated feature that might persist beyond the resolution of language deficits, manifesting, in many cases, with some features reminiscent of the syndrome of speech dyspraxia. The chronic picture is “deficits in the smoothness with which vocalization of one phoneme in a series can be ceased and changed to the next, in precise control of the respiratory component of vocalization, and/or in precise positioning of the oral cavity to produce desired phonemes … better explained by inadequacy in skilled execution of movements, an apraxia in speaking … but not an associated disorder in language usage.”6 This resembles Luria’s idea of efferent motor aphasia, in which the primary disorder relates to skilled sequential movements or kinetic melodies in which the patient is able to position the articulators correctly but is not capable of moving smoothly from one articulatory position to the next.7 Originally, Pierre Paul Broca used the term aphemia to refer to this condition. There appears to be a revival in the use of this term in relation to progressive speech disturbances. Michael Alexander’s group at Boston University has taken the view that aphemia is a distinctive syndrome arising from small lesions in the left inferior frontal gyrus (pars opercularis), inferior precentral gyrus, and underlying white matter.8

The main features of speech dyspraxia are shown in Table 3-5.

Functional neuroanatomy of speech dyspraxia

It is now recognized that articulatory function depends on a hierarchically organized network of structures involving cerebellum, thalamus, striatum, anterior insula, and sensorimotor cortex. Current concepts of Broca’s area, particularly the posterior portion (Brodmann’s area 44) abutting on the precentral sulcus (Brodmann’s area 6), include the view that it mediates the encoding of phonological word forms into articulatory plans. This places it at the apex of the articulatory hierarchy. Broca’s area also shows increased activity during syntactic processing, although lesions restricted to this area cause impairments in speaking rather than language,6 a view dramatically foreshadowed by the neurologist Pierre Marie in 1906 with a paper titled “The Third Frontal Convolution Does Not Play Any Special Role in the Function of Language” (see Harrington). Functional neuroimaging findings have raised the possibility that Broca’s area represents a bridge between articulation and language production.

The Syndrome of Broca’s Aphasia

Repetition is impaired and reflects essentially the same pattern of nonfluency as is that in spontaneous language. Written language is also agrammatic, with graphemic and graphomotor errors. Comprehension in Broca’s aphasia is not unscathed, but it nevertheless serves the patient comparatively well in daily life, and comprehension deficits are not a particularly noticeable feature of the clinical encounter. Some authorities have argued that there is a unitary impairment that produces both expressive agrammatism and syntactic comprehension deficits. There are cases, however, in which expressive agrammatism and comprehension dissociate, which suggests that there are separate mechanisms for elaborating syntactic form in language production and for appreciating syntactic form in heard or read language and that these mechanisms can be separately impaired. Gesture and communicative pragmatics (i.e., all of the nonverbal behaviors that accompany language appropriate the communicative context) are usually preserved.

The syndrome of Broca’s aphasia can be observed as a later consequence of infarction. The initial clinical picture resembles a global aphasia. After weeks or months, there is a gradual emergence of the dyspraxic and agrammatic features, and these evolve slowly toward the long-standing features of the syndrome of Broca’s aphasia (see Mohr,6 page 230).

Functional neuroanatomy of Broca’s aphasia

Broca’s aphasia is typically produced by fairly large lesions in the territory of the superior division of the left middle cerebral artery. Right hemiparesis, particularly involving the face and arm, is typically present as a neighborhood sign. Broca’s area, the anterior insula, and the basal ganglia are often all damaged, and the lesion usually also includes the middle frontal gyrus and the anterior parietal lobe. Involvement of Broca’s area alone is not a sufficient condition for the emergence of the syndrome of Broca’s aphasia. Neuroimaging findings have suggested that damage to Broca’s area impairs the production of all forms of speech (propositional and nonpropositional; see Blank et al, 2002). Propositional speech refers to newly formulated language output that conveys an idea, as opposed to nonpropositional speech, which is more automatic in nature and conveys nonideational content such as feeling states. At a clinical level, it is well accepted that propositional speech is most severely affected and that automatic nonpropositional aspects of speech are often preserved. Grammatical output depends on the interaction between Broca’s area and other cortical regions. Functional neuroimaging in normal subjects demonstrates that the middle frontal gyrus is commonly activated by language tasks that activate Broca’s area, which suggests that this region should also be included in a language production network (see Blank et al., 2002). Tractography of the arcuate fasciculus suggest that this pathway terminates in the middle frontal and inferior precentral gyri (Fig. 3-1), as well as in classically defined Broca’s area (see Catani et al., 2005).

Figure 3-1 Terminations of the arcuate fasciculus suggested by tractography.

(From Catani M, Jones DK, Ffytche DH: Perisylvian language networks of the human brain. Ann Neurol 2005; 57:8-16, Fig. 3. Copyright © 2006 Wiley-Liss, Inc., A Wiley Company. Reprinted with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.)

Nonfluent Production with Normal Repetition: Transcortical Motor Aphasia

The Syndrome of Transcortical Motor Aphasia

There is general agreement that there are two variants of TMA.10 The first often manifests initially as mutism, which resolves to poorly initiated and nonfluent output, characterized more by an articulatory disturbance than by a language disturbance. Output is normal during repetition. Comprehension and naming are also well preserved. There is some debate as to whether this form of TMA is a true aphasia. It occurs with infarcts in the territory of the left anterior cerebral artery, particularly with involvement of the supplementary motor area. It also occurs after resection of the left supplementary motor area. This variant of TMA has been ascribed to isolation of the supplementary motor area from frontal perisylvian language mechanisms. In this view, isolation of the supplementary motor area results in impaired motor programming before the overt execution of language output.11

The second variant of TMA is characterized by very sparse language production, which gives the impression of a reduced intention or motivation to speak. What speech is produced is well articulated but with impoverished syntax and narrative. Nevertheless, repetition is normal, even for long and complex sentences. Although patients with this form of TMA do not initiate routine series (e.g., naming the months of the year, nursery rhymes) on request, they freely complete the series after the examiner has provided the first few elements. Similarly, they are able to fill in sentence frames provided by the examiner (e.g., “the day is __________ and the sun is __________”). Luria referred to this condition as dynamic aphasia.7 He believed that the underlying impairment was an inability to elaborate the linear scheme of sentences or, in current terms, an inability to elaborate propositions. Luria’s description of the production difficulties of this group of patients is instructive:12

“As a rule, these patients answer simple questions relatively easily, frequently prefacing their reply with an echolalic* repetition of the question, but they have difficulty as soon as they are asked to read a text and relate it to the examiner, or to compose a story from a picture given to them, and they are completely helpless if they have to write an essay on any freely chosen subject. In these cases they state that their thoughts will not move, that nothing enters their head, and they usually abandon the task or do nothing more than reproduce some habitual verbal stereotype, usually taken from their past experience.”

Fluent Production with Impaired Repetition and Comprehension: Wernicke’s Aphasia and Pure Word Deafness

The Syndrome of Wernicke’s Aphasia

The following is a list of core features accepted in current practice:

Output is fluent, often empty of substantive meaning, with an excess of closed class words and circumlocutions.

Output is fluent, often empty of substantive meaning, with an excess of closed class words and circumlocutions. Paraphasias are common. These may be phonemic (literal) or semantic, but the former is held to be the most frequent type. Paraphasias may be so severe that jargon is produced (jargonaphasia). Similar output features are seen in writing, which, however, displays preserved penmanship.

Paraphasias are common. These may be phonemic (literal) or semantic, but the former is held to be the most frequent type. Paraphasias may be so severe that jargon is produced (jargonaphasia). Similar output features are seen in writing, which, however, displays preserved penmanship. Patients appear to be unaware of or unconcerned about their highly disturbed and often nonsensical output, in contrast to the frustration shown by those with Broca’s aphasia.

Patients appear to be unaware of or unconcerned about their highly disturbed and often nonsensical output, in contrast to the frustration shown by those with Broca’s aphasia. Comprehension is severely impaired, predominantly because of a difficulty in discriminating between phonemes. The profundity of the comprehension impairment makes this the most disabling feature of Wernicke’s aphasia. As a consequence of the comprehension difficulty, output during attempts at conversation is seldom related to the conversational context. Some patients respond on the basis of incidental nonlinguistic cues.

Comprehension is severely impaired, predominantly because of a difficulty in discriminating between phonemes. The profundity of the comprehension impairment makes this the most disabling feature of Wernicke’s aphasia. As a consequence of the comprehension difficulty, output during attempts at conversation is seldom related to the conversational context. Some patients respond on the basis of incidental nonlinguistic cues.The following is an example of the fluent output disorder of a patient with severe Wernicke’s aphasia, illustrating runs of paragrammatism:13

Fluent Production with Normal Comprehension and Impaired Repetition: Conduction Aphasia

The syndrome of conduction aphasia is perhaps the most controversial of the aphasias. It was postulated as a theoretical possibility from the Wernicke-Lichtheim model. In essence, Wernicke assumed that if the pathway connecting Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas were to be interrupted, speech would be fluent but paraphasic, and comprehension would be preserved, but the patient would be unable to repeat what he or she heard. This disconnection concept was challenged, principally by Sigmund Freud, who held that conduction aphasia, to the extent that this syndrome actually existed, was more likely to be the result of cortical damage and that its exact character would depend on the proximity of the lesion to either Broca’s or Wernicke’s areas. This notion has been revisited in light of tractography studies of the arcuate fasciculus (see Catani et al, 2005).

Conduction aphasia is fundamentally a disorder of repetition. The breakdown in repetition has two underlying causes, giving rise to two variants of the syndrome: reproduction conduction aphasia and repetition conduction aphasia. Reproduction conduction aphasia is a specific disorder of phonological processing in which the processes by which the perceived phonemic representation of a word is converted into articulatory sequences are impaired. Repetition conduction aphasia, or acousticomnestic aphasia in Luria’s classification,7 is considered to be a disorder in a particular aspect of short-term memory: namely, reduced capacity to pass information from a short-term acoustic store to the output system. From a cognitive perspective, both forms of the syndrome involve a breakdown in a privileged communication channel. From a neuroanatomical perspective, the notion that this channel is necessarily the arcuate fasciculus, a deep white matter pathway that was initially thought to connect Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas, has been remarkably persistent in neurological thinking, but the clinicoanatomical literature indicates that there is no reason to believe that arcuate fasciculus interruption is a more feasible explanation for conduction aphasia than are lesions in the perisylvian language cortex.

The Syndrome of Conduction Aphasia

The core clinical features of reproduction conduction aphasia are as follows:

Against this background, repetition of words, phrases, and sentences, as well as writing in response to dictation, is very impaired and is hampered by prominent phonemic paraphasias. Phonemic paraphasias are also seen in naming and reading.

Against this background, repetition of words, phrases, and sentences, as well as writing in response to dictation, is very impaired and is hampered by prominent phonemic paraphasias. Phonemic paraphasias are also seen in naming and reading. Characteristic attempts are made to correct the phonemic selection errors by successive approximations, or conduit d’approche (see Table 3-3). This phenomenon suggests that the representation of phonological knowledge is intact in conduction aphasia and that the impairment lies in the integration of phonology with articulatory processing.

Characteristic attempts are made to correct the phonemic selection errors by successive approximations, or conduit d’approche (see Table 3-3). This phenomenon suggests that the representation of phonological knowledge is intact in conduction aphasia and that the impairment lies in the integration of phonology with articulatory processing.The following example of fluent output in a conduction aphasic illustrates the profuse phonemic paraphasias and conduit d’approche:13

EXAMINER: Tell me what’s going on in this picture.

PATIENT: Oh … he’s on top o’ the ss … ss … swirl … it’s a … ss … sss … ss … sweel … sstool … stool.

Neuroanatomy of Conduction Aphasia

Most cases with conduction aphasia have lesions centered on the supramarginal gyrus. The lesion can include white matter deep to the supramarginal gyrus, involving the posterior end of the arcuate fasciculus. Whether involvement of the posterior arcuate fasciculus is a necessary condition is debatable. Anterior transection of the arcuate fasciculus does not produce conduction aphasia. Lesions in the insular cortex, including subinsular white matter, are also an important cause of conduction aphasia. It is recognized that conduction aphasia can occur with pure suprasylvian or pure subsylvian lesions (see Benson and Ardila, 1996).

Fluent Production with Normal Repetition and Impaired Comprehension: Transcortical Sensory Aphasia

TSA is a rather controversial condition. It is similar to all posterior aphasias in the sense that it manifests as a fluent language disturbance, which ranges from severely paraphasic and circumlocutory speech to relatively normal output with occasional semantic paraphasias. The hallmark of TSA is impaired comprehension but well-preserved repetition. Patients with TSA are able to repeat long and complex sentences that they cannot comprehend. The pattern of cognitive breakdown in TSA is variable, which suggests that this is not a single entity. Location of the causative lesion is also not certain and might be more widely distributed than classical aphasiologists suspected. Computed tomographic evidence suggests that lesions producing TSA tend to overlap in the inferior region of the temporo-parieto-occipital junctional cortex, as well as occipitotemporal cortex and underlying white matter. This inferior and medial distribution implicates the posterior cerebral artery.14 Other affected patients have lesions that are more superolateral, lying in the posterior watershed region between the posterior and middle cerebral arteries.14 TSA is also associated with degenerative conditions, such as the posterior cortical atrophy variant of Alzheimer’s disease.15

Fluent Production, Normal Repetition, and Preserved Comprehension: Anomic Aphasia

Norman Geschwind’s adaptation of the Wernicke-Lichtheim model attributed the role of name retrieval to the angular gyrus, which is widely recognized as a zone of convergence for visual, auditory, and tactile information and a repository for semantic information. It is anatomically well placed as a nodal structure for the activation of semantically specified concepts. It is richly interconnected with the posterior temporal region, where activated concepts are converted to phonemic form. Angular gyrus lesions produce the features of anomic aphasia, but it is recognized that dysnomic features can arise from multiple loci and are therefore poorly localizing. In the author’s own experience, however, extra-angular lesions seldom produce the prominent fluent and circumlocutory output disturbance of anomic aphasia. For example (in which the patient attempts to convey that he suffered a stroke after aortic surgery):13

EXAMINER: Can you tell me about your illness?

EXAMINER: And it was after the operation?

PATIENT: Right, about a day later, while I was under whatchmacall. …

Nonfluent Production, Normal Repetition, and Impaired Comprehension: Mixed Transcortical Aphasia

The syndrome of mixed transcortical aphasia was initially described in 1948 by Kurt Goldstein, although the condition had been anticipated by the classical aphasiologists. There is a severe reduction in the quantity of spontaneous output; comprehension is also severely impaired, but repetition remains intact. This pattern of impairment was ascribed to isolation of the speech area, a concept that was later to be confirmed by Geschwind in his classic study of a case of carbon monoxide poisoning. Repetition is made possible by the integrity of the perisylvian language axis: namely, Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas and the connections between them. Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas are, however, disconnected from anterior and posterior association cortices that mediate the ideational basis of language. Functional neuroimaging findings support the notion of a widely distributed left-lateralized extrasylvian neocortical system involved in the formulation of propositional language before its conversion to articulated speech (see Blank et al., 2002). Echolalia is a prominent component of mixed transcortical aphasia and, like intact repetition, can be thought of as reflecting the preservation of the automatic aspects of language, devoid of an ideational context.

PRIMARY PROGRESSIVE APHASIA

Primary progressive aphasia refers to a gradually evolving aphasia, in the absence of other cognitive disorders. It is often the first symptom of neurodegenerative conditions such as one of the forms of frontotemporal dementia (see Chapter 73).

The term primary progressive aphasia is applied when the speech and language symptoms have progressed for about 2 years in the absence of any other cognitive or behavioral changes.16 Even when the underlying dementia begins to manifest, the aphasic disturbance remains the most prominent and disabling symptom. Although some studies suggest that 50% to 60% of primary progressive aphasia cases have a fluent disturbance, at least two variants (fluent and nonfluent forms) are currently acknowledged. A third logopenic variant (characterized by slow and halting word production in the context of highly simplified but grammatically correct sentences) has also been proposed.

Mesulam16 estimated that the underlying neuropathology in about 60% of patients with primary progressive aphasia is neuronal loss, gliosis, and spongiform change. Some cases are caused by frontotemporal dementia with parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (see Chapter 74), a genetic tauopathy. A further 20% have Pick’s disease, and fewer than 20% have Alzheimer’s disease.

Fluent Progressive Aphasia: Semantic Dementia

In semantic dementia, spontaneous language is fluent, dysnomic, and possibly circumlocutory, but production and comprehension of syntax are normal. The hallmark feature is a loss of word meaning, underpinned by a degradation of semantic function. On confrontation testing, for example, patients not only are anomic but also are unable to give any of the attributes of the object. The intended word is often replaced by a superordinate category (e.g., “flower” instead of “daisy”), which reflects an early loss of subordinate knowledge. Speech itself is normal in terms of rate of production and articulation. Published consensus criteria for the diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia link semantic dementia with disorders of object and face recognition (visual agnosia and prosopagnosia, respectively) as additional manifestations of semantic loss.17 This is controversial with regard to the definition of primary progressive aphasia mentioned previously.16

Nonfluent Progressive Aphasia

Most patients with nonfluent progressive aphasia and pure progressive aphemia have been shown to have Pick’s disease, with more restricted atrophy in the latter group.18 Both conditions are regarded as frontotemporal dementia variants17 and may represent a clinical spectrum reflecting varying degrees of damage to the anterior insular, inferior premotor cortex, and pars opercularis.

An Intermediate Variant: Logopenic Progressive Aphasia

Further definition of primary progressive aphasia variants is likely to continue (see Grossman, 2002). Because primary progressive aphasia is an evolving language disorder, distinctions between the variants might be stage related. On the basis of a longitudinal study, Kertesz and colleagues suggested that although the aphemic, logopenic, agrammatic, and semantic distinctions are useful, there is some tendency for outcomes to converge as the dementia progresses.19

ACQUIRED DISORDERS OF READING: THE ALEXIAS

The Dual-Route Model and Reading Disorders: Deep and Surface Alexias

Deep Alexia

The main features of deep alexia are as follows:

Normal reading of familiar and highly imageable words, regardless of whether they have regular (“desk”) or irregular (“yacht”) grapheme-phoneme correspondence.

Normal reading of familiar and highly imageable words, regardless of whether they have regular (“desk”) or irregular (“yacht”) grapheme-phoneme correspondence. Inability to read pseudowords correctly according to the usual grapheme-phoneme conversion rules of the language.

Inability to read pseudowords correctly according to the usual grapheme-phoneme conversion rules of the language.Surface Alexia

Deep alexia and surface alexia are regarded as central alexias, because they represent a loss of access by visual representations of word forms to central phonemic and semantic mechanisms (Table 3-6).

| Psycholinguistic Syndrome | Deficit | Closest Equivalent Neurological Syndrome, or Lesion Location |

|---|---|---|

| Deep alexia | Loss of grapheme-to-phoneme conversion | Alexia with agraphia |

| Aphasic alexia | ||

| Surface alexia | Loss of visual word form access to semantic system | Left temporoparietal |

| Generalized atrophy | ||

| Primary progressive aphasias |

Neurological Classification of Alexias

There is an alternative, nonpsycholinguistic classification system for the alexias. Although some syndromes are essentially the same in both (e.g., pure alexia), there really is no equivalent syndrome in the other classification system for others (see Benson and Ardila, 1996, for suggested correlations between the two classification systems).

Alexia without Agraphia (Pure Alexia)

Patients with pure alexia read by sequentially identifying the letters of the word (letter by letter reading). This is a slow and laborious process, and at least in the subacute phase, silent reading is not possible. Speed of reading depends on the number of letters in the word (word length effect); therefore, whole-word recognition is not possible. All other language functions are well preserved, giving rise to the term pure alexia. Writing is also intact, but the patient is not able to read what he or she has written. The classical lesion in pure alexia is infarction of the medial surface of the left occipital lobe and splenium of the corpus callosum. It is now accepted that splenial involvement is not a necessary condition for the emergence of pure alexia.

ACQUIRED NEUROGENIC AGRAPHIA

Most classifications have recognized agraphias associated with aphasic syndromes (aphasic agraphias), those associated with fundamental visuospatial disorders (e.g., neglect), and those associated with upper limb motor disorders and dyspraxic disorders. Benson and Ardila (1996) proposed a dichotomous classification, into aphasic and mechanical agraphias (Table 3-7).

Based on Benson DF, Ardila A: Aphasia: A Clinical Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996, p 214, Table 12.1.

The mechanical agraphias raise the question as to whether writing impairments of nonsymbolic origin (such as dystonic, paretic, or apractic forms) should be regarded as true agraphias, which is, again, reminiscent of the question of whether speech dyspraxia should be regarded as aphasic or dysarthric. Perhaps the term agraphia should be reserved for language-based disturbances in writing and graphomotor impairment for nonlinguistic disturbances. Table 3-8 lists the main characteristics of some of the aphasic agraphias, and Table 3-9 lists characteristics of the higher-level mechanical agraphias.

TABLE 3-8 Characteristics of Aphasic Agraphia: Comparison with Spoken Output

| Spoken Output | Written Output |

|---|---|

| Agraphia in Broca’s Aphasia | |

| Sparse output | Sparse output |

| Effortful | Effortful |

| Poor articulation | Clumsy calligraphy |

| Short phrase length | Abbreviated output |

| Dysprosody | (No written equivalent) |

| Agrammatism (lack of closed class words) | Agrammatism (lack of closed class words) |

| Poor spelling | Poor spelling |

| Agraphia in Wernicke’s Aphasia | |

| Normal vocal characteristics | Normal graphic characteristics |

| Noneffortful speech | Noneffortful writing |

| Good articulation | Well-formed letters |

| Normal phrase length | Normal sentence length |

| Normal prosody | (No written equivalent) |

| Lack of open class (substantive) words | Lack of open class (substantive) words |

| Paraphasias | Paragraphias |

Adapted from Benson DF, Ardila A: Aphasia: A Clinical Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996, pp 218-219, Tables 12.3 and 12.4.

TABLE 3-9 Apractic and Spatial Agraphias

|

Spatial delimiters between words are not used correctly (“Th esunis shi ning” instead of “The sun is shining”)

|

Neurocognitive Classification of Agraphias

Neuropsychological studies have resulted in an alternative classification of the agraphias, analogous to the psycholinguistic classification of the alexias. The distinction is made between central and peripheral agraphias, with matching of the concepts of central and peripheral alexias. Spatial and apractic agraphia can be regarded as peripheral because they do not involve fundamental language mechanisms. Table 3-10 summarizes the central agraphias.

| Syndrome | Linguistic Impairment | Neuroanatomy |

|---|---|---|

| Lexical agraphia (analogous to surface dyslexia) | Loss of whole word processing | Dominant angular gyrus, with sparing of immediate perisylvian region |

| Inability to spell irregular or ambiguous words, with preserved spelling of regular words and graphemically legal nonwords | ||

| Graphemic regularization (for example, “grayshus” instead of “gracious”) | ||

| Phonological agraphia (analogous to phonological dyslexia) | Loss of sublexical processing | Dominant supramarginal gyrus and insula |

| Impairment of phoneme-to-grapheme conversion | ||

| Inability to spell nonwords, with preserved ability to spell regular and irregular familiar words | ||

| Deep agraphia (analogous to deep dyslexia) | Inability to write nonwords or words with low imageability | Large supramarginal or insula lesions |

| Semantic paragraphias with no visual similarity to the target (for example, “travel” instead of “car”) |

Benson DF, Ardila A. Aphasia: A Clinical Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Blank SC, Scott SK, Murphy K, et al. Speech production: Wernicke, Broca, and beyond. Brain. 2002;125:1829-1838.

Catani M, Jones DK, Ffytche DH. Perisylvian language networks of the human brain. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:8-16.

Duffy JR. Motor Speech Disorders: Substrates, Differential Diagnoses, and Management, 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby, 2005.

Grossman M. Progressive aphasic syndromes: clinical and theoretical advances. Curr Opin Neurol. 2002;15:409-413.

LaPointe LL, editor. Aphasia and Related Neurogenic Language Disorders, 3rd ed., New York: Thieme, 2005.

1 Brown JW. Case reports of semantic jargon. In: Brown JW, editor. Jargonaphasia. New York: Academic Press; 1981:171.

2 Luria AR. Language and Cognition. New York: Wiley & Sons, 1982;224.

3 Head H. Aphasia and Kindred Disorders of Speech. vol 2. London: Cambridge University Press; 1926:229.

4 Goodglass H. Agrammatism. Whitaker H, editor. Studies in Neurolinguistics. vol 2. New York: Academic Press; 1976:238.

5 Kertesz A. The anatomy of jargon. In: Brown JW, editor. Jargonaphasia. New York: Academic Press; 1981:91.

6 Mohr JP. Broca’s area and Broca’s aphasia. Whitaker H, editor. Studies in Neurolinguistics. vol 1. New York: Academic Press; 1976:221.

7 Kagan A, Saling MM. An Introduction to Luria’s Aphasiology: Theory and Application. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes, 1992.

8 Schiff HB, Alexander MP, Naeser MA, Galaburda AM. Aphemia: Clinical-anatomic correlations. Arch Neurol. 1983;40:720-727.

9 Harrington A. Medicine, Mind, and the Double Brain. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1987;261.

10 Ardila A, Lopez MV. Transcortical motor aphasia: one or two aphasias? Brain Lang. 1984;22:350-353.

11 Cimino-Knight AM, Hollingsworth AL, Gonzalez-Rothi LJ. The transcortical aphasias. LaPointe LL, editor. Aphasia and Related Neurogenic Language Disorders. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme; 2004:169-185.

12 Luria AR. Human Brain and Psychological Processes. New York: Harper & Row, 1966;358-359.

13 Goodglass H, Wingfield A. Word-finding deficits in aphasia: brain-behavior relations and clinical symptomatology. In: Goodglass H, Wingfield A, editors. Anomia: Neuroanatomical and Cognitive Correlates. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1997:7.

14 Kertesz A, Sheppard A, McKenzie R. Localization in transcortical sensory aphasia. Arch Neurol. 1982;39:475-478.

15 Benson DF, Davis RJ, Snyder BD. Posterior cortical atrophy. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:789-793.

16 Mesulam MM. Primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:425-432.

17 Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51:1546-1554.

18 Hodges JR, Davies RR, Xuereb JH, et al. Clinicopathological correlates in frontotemporal dementia. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:399-406.

19 Kertesz A, Davidson W, McCabe P, et al. Primary progressive aphasia: diagnosis, varieties, evolution. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2003;9:710-719.

* Echolalia is the patient’s tendency to echo what the examiner says but to change the grammar to suit himself or herself. For example, in response to the examiner’s question “How are you feeling?” the patient may reply, “How am I feeling?” Logoclonia is the tendency to repeat the final syllable of a word. For example, “telephone … phone … phone.”